1. Introduction

An important aspect of the institutional arrangement of the water sector (WSS) is the different degrees of private sector participation (PSP) in the provision of the corresponding services and infrastructure [

1]. Issues of cost, efficiency, and investment are usually arguments in favor of private participation in service delivery. Limitations on public budgets and greater management efficiency by the private sector, by its very nature, and objectives of cost recovery and return on investment, are part of this context. The existing public resource limitations added to aging existent infrastructures, climate, and demographic changes increase the necessity for investments, creating urgency in applying new sources.

In Brazil, the issue that bothers and mobilizes the actors around PSP, which to this day is very low in the country and tremendously low in stormwater management, is the low degree of inclusion or poor universality of the services and weak quality of the services provided. Without addressing other and diverse reasons for this poor performance, the debate has been restricted to questioning what types of providers could break this cursed logic that has resulted in 35 million people without access to water and over 100 million without access to sanitation services, with consequent impacts on the health and economy of Brazilians. The panorama in stormwater management is even worse [

2]. If only the change in the origin of the capital invested and the execution of well-designed contracts between the municipalities and operators were sufficient to achieve universal access and the provision of quality services, everything would be solved the next day, but the reality is quite different and PSP, although it is welcome and should have coherently constructed contracts, requires much more than that, and provides challenges that must be gradually overcome, some of which are presented in this research.

In the case of urban drainage, due to its unique characteristics, the complexity brought about by its interrelationships with other sectors such as urban planning, health, and economy, and its low level of institutionalization, including possible economic and financial support through pricing, the design of PSP is a subject that requires intelligently creative and innovative solutions, with different local aspects that make defining its approach in a single text practically impossible.

Throughout the 1990s, PSP in the WSS was widely considered to be the solution to sectoral problems, specifically the lack of investment and inefficiency, but in the following decade, the vision changed due to several reasons, among them the insufficient engagement with finance in developing countries and the lack of clear conclusions about the benefits of this participation.

The World Bank emphasized in a 2003 Operations Evaluation Department report that: “Private Sector Participation (PSP) is not a panacea to deep-seated problems and cannot be expected to substitute for decisions that only have the power and obligation to make. PSP is better likened to a sharp tool. A capable government can use it to great advantage to improve the water supply and sanitation situation but an inept government can make worse through an injudicious use of PSP without providing clear quality and price regulation and lending strong and sustained support to PSP” [

3].

Usually, the question of whether services are provided through public or private initiative takes second place, because the population primarily wants services to be subject to good performance, including their governance, which leads to expected good results through the execution of the objectives outlined by public policies and good decisions made by those responsible for them [

4,

5].

The relationship between political governance and WSS governance and performance aspects in the provision of services, such as the expansion of coverage and the efficiency of providers, should be analyzed, as their impacts can be either positive or not. In political governance, institutions—as the main actors—shape the relationship between citizens and government actors (political rights and electoral systems) and the rules that determine government organization (separation of powers, checks, and balances), and in WSS governance the main aspects are institutions, borders, and coordination in the participation of actors. Institutions are the main elements of governance as they shape the behavior of the actors responsible for policy-making and policy decision-making. In WSS governance, in addition to the coordination between the actors responsible for policy-making, services provision, and regulation, the participation of users and the definition of boundaries between all actors are important [

5].

In practice, the degree to which the existence of PSP has a positive contribution to the provision of the WSS depends on the overall country environment and institutional context [

6]. In Chile, for example, before privatization, as public providers, there was a good quality of political governance and governance of the WSS [

3]. There are examples of successes and failures of public and private participation (Buenos Aires, Paris, and Berlin) in a pendulum movement, depending on each context [

7].

Europe, starting in the 1990s with the Urban Wastewater Collection and Treatment Directive (UWWD), following the concept of sustainability defined by the UN, added environmental, ethical, and equity costs to economic ones.

The so-called three E’s—economics, environmentalism, and ethics and equity [

8]—can be summarized in the form of questions posed by water policy analysts (EUROWATER partnerships):

If we do invest enough, what impact will this have on water bills?—Economic Issue

How much more should be raised to upgrade environmental performance?—Environmental Issue

If all sustainability costs are to be passed on to users, can they afford it, and is it politically acceptable?—Ethics and Equity Issue [

8].

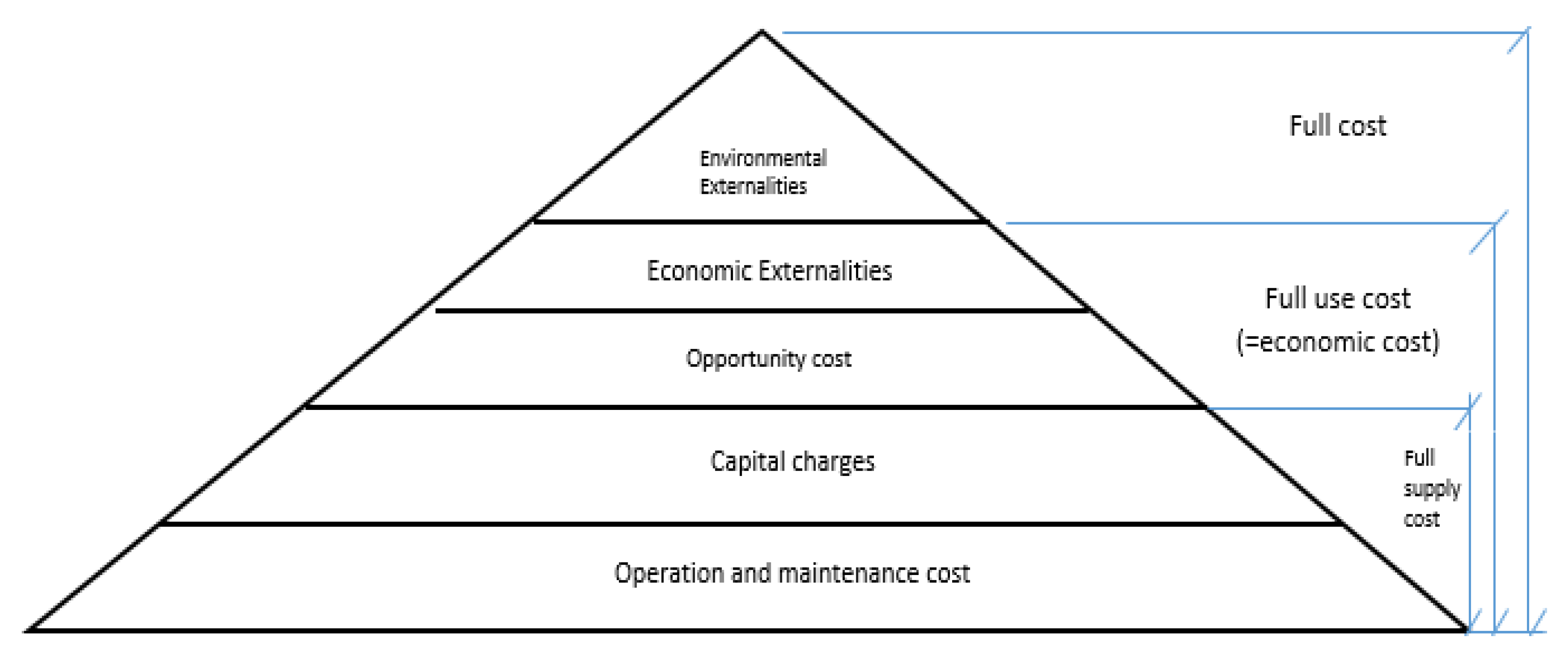

As one of the advantages listed for private participation (greater efficiency and flexibility in management and investment capacity), traditional costs are well known and usually taken into account (full supply costs). However, with the discovery of other costs, hidden by the former, the new distribution of costs, as shown in

Figure 1, including those impacted by a new distribution of risk between public and private participants, deserves to be reviewed to achieve the economic and financial sustainability of the WSS [

9]. This sustainability could be achieved using equilibrium between costs and sustainable value in the use of water which should be equal to the full cost [

10].

The revisited new composition of the total cost parcels, to achieve economic and financial sustainability, must not only cover the determination of which portion should be borne by users—i.e., being collected by local governments, their concessions and partnerships, and through tariffs including subsidies—but also which portion should remain with all taxpayers, through taxes collected for the general budget of the states.

On-site stormwater treatment and use is an additional alternative to traditional systems, for example, with separate systems, one for stormwater runoff and the other for wastewater, or combined treatment systems. However, from the moment that stormwater started to be seen as a resource and was made available for potable and non-potable uses, a higher degree of complexity was added to the calculation of costs for each parcel, public or private, making the design of the financial and economic sustainability of urban stormwater management systems more complex than that of potable water supply and sanitary sewerage [

11]. Furthermore, in most municipalities, there is no breakdown of costs, as they are practically unknown, which makes it difficult to calculate them for various purposes, including those related to possible contracting or partnerships with private entities.

In cities where economic sustainability is based, at least in part, on one of the three Ts of the triple bottom line of service delivery systems—tariffs, taxes, and transfers [

12]—charging for urban stormwater management costs can be determined in several ways.

It can be calculated, for example, from the volume of water supplied, as is performed in many places for the costs of runoff and wastewater treatment systems, or based on estimates of the amount of surface area in each plot, as is the case with most stormwater utilities in the USA and Canada [

13]. Thus, methods are usually used to estimate the volume of runoff from lots considering, in addition to the area (total and sealed), infiltration factors, use (e.g., residential, commercial), property value, and several other factors, or just by applying a fixed value not always linked to any specific parameter, but in general linked to operating and maintenance costs and sometimes necessary capital investments. The other types of costs—environmental, ethical, and equity—remain a challenge so far.

This article aims, through the discussion of case studies, to present some existing forms of private participation in the management of urban drainage services in different places—some of which are still under construction and in progress, but with potential for success—and to contribute to ongoing discussions, providing evolution for the subject and consequently for the sector. Particularly, it discusses the Brazilian case study, shedding light on the main issues and offering recommendations for PSP success.

The subject is organized into five sections in addition to this brief introduction. Section two deals with the attractiveness and efficiency of PSP.

Section 3 and

Section 4 set out international and Brazilian experiences.

Section 5 summarizes and discusses the results of international experiences, focusing on the Brazilian experience. Finally,

Section 6 draws the main conclusions of the paper.

2. Attractiveness and Efficiency

In the private sector, the driver for attractiveness is the opportunity to monetize capital, while in the public sector, it is the search for the best service provision along with lower costs, and greater breadth and equity. Thus, attractiveness is linked to the costs involved, whether purely economic, environmental, or social.

Investment costs are more significant than maintenance costs; however, those related to flooding should be accounted for, even if under the heading of environmental expenses. For combined systems, which are still the majority (50% or more), the expense of overloading treatment facilities during flooding also deserves to be factored in.

Concerning efficiency, in the private sector, there are management standards represented by extensive voluntary standardization (e.g., ISO 9001 and ISO14001), and in the public sector, this is mostly achieved through regulatory requirements [

14].

In Brazil, however, the absence of precise information on the demand for drainage services leads to cost estimates based on the calculation of average production costs, prioritizing the financing of the system and cost recovery, i.e., neglecting efficiency, since all expenses (necessary or not) are distributed by the customers of the services, which is a disadvantage in terms of not taking advantage of the capacity to produce efficiency in PSP. The option of estimating an average cost is considered a second-best solution, if compared to the alternatives of social marginal cost or cost according to marginal benefit that considers price–demand elasticities. One advantage of PSP in drainage is the possibility of rescuing the idea of efficiency in urban land use through the quantification of the costs involved in its sealing.

In PSP, there is a division or sharing of risks between the public and private sectors, as in the case of PPP arrangements, which have been extensively discussed, where the presence of guarantees provided by partners is intended to reduce risk; this is understood as the multiplication of the probability of occurrence by the magnitude of the impact caused if the risk in question were to occur. In the case of the participation of the private owners of the lots, through their reduction in flow or even their total disconnection, the costs of the devices implemented in the lot may be borne by the private owner or receive incentives such as a reduction in tariffs or subsidies for their implementation. It should be taken into account that there will always be centralized systems and that, therefore, not all actors should be encouraged to disconnect because the systems would stay without resources; that is, there is an ideal number of incentives for each location.

Another form of PSP is the partial or total privatization of companies belonging to public authorities, as is currently happening in Brazil, the most recent case being that of the Rio de Janeiro State Water and Wastewater Company (CEDAE), which was put up for public auction in which a concession was offered as payment to the state, but without any link to the application of resources in the sector. The company was granted a long-term concession through an extendable contract.

PSP can also be made by offering shares on the stock exchange, as in the case of the Companhia de Saneamento Básico do Estado de São Paulo (SABESP) which has shares in the São Paulo and New York stock exchanges. In this case, an inconvenience concerns the profit distribution percentages that sometimes exceed the minimum stipulated in regulations. Thus, the reasons for not making investments to reach the universalization of services or to execute works to improve quality and resilience in times of scarcity are questioned. The participation of private capital through shares quoted in the market urges management to seek efficiency, as demonstrated through profitability with consequent valuation and attractive investments, but the balance between the necessary investments to serve the customers, the tariff affordability, the expansion of the operation, and the profits to be distributed using dividends to the shareholders require professional management. In this scope, drainage is left to the municipalities with no such participation in the market, requiring new, creative, and attractive solutions that sensitize the actors with potential interest.

Finally, an important factor of attractiveness is the existence of public policies that favor PSP, such as flow reduction policies, because they signal a reduction in fixed expenses (with less construction and equipment) which, over time, generate a reduction in variable expenses for the operation and maintenance of these infrastructures, that is, a reduction in total costs. On the contrary, negligence in this area becomes very expensive because by not designing a policy to restrict the increased inflows, the growth of costs and eventually inefficiency is accepted with a possible reduction in attractiveness to PSP.

In addition to cost reduction policies, there are policies to increase revenues such as rainwater reuse or utilization policies, which are considered policies that increase the attractiveness of PSP.

The use of the analysis tool based on the SWOT matrix, originally developed for strategic business and marketing planning, but also used in participatory planning [

15] can be adopted for checking possible scenarios and policies for PSP in stormwater. Based on internal factors (strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (threats and opportunities), prospective scenarios are elaborated from combinations of these factors. The combination of (internal) strengths with (external) opportunities produces a first, so-called aggressive, or maxi–max scenario in which strengths and opportunities are maximized. A second scenario in which the weaknesses (internal) are combined with the opportunities (external) produces a conservative or mini–max strategy, in which the maximized opportunities (external) must compensate for the weaknesses (internal) that are aimed to be minimized. In the third scenario, the strategy, called competitive, or maxi–min, the strengths (internal) and the threats (external) are combined and, in this scenario, the management of the strengths seeks to avoid the materialization of the threats. Finally, the combination of weaknesses (internal) and threats (external) produces a defensive strategy, or mini–mini, which seeks to minimize both weaknesses and threats [

16].

Without exhausting all of the aspects present in PSP in stormwater management, just as an example, we produced a SWOT matrix according to

Figure 2 below.

An example of a max–max aggressive strategy of forces and opportunities could be the design of a policy to encourage the use of rainwater as a resource (external opportunity) and the intense use of private resources (internal strength) to finance storage devices on plots through incentives to the owners.

A second example of a conservative or min–maxi strategy can be seen through the use of a policy of publicizing stormwater utility (internal weakness) combined with the intensified construction of stormwater amenity sites such as retention basins (external opportunities).

The competitive or max–mini strategy (reinforcing internal strength), e.g., building works and equipment against floods and spreading preparedness for climate change and future uncertainties (external threat), is the third scenario.

The fourth scenario is defensive or mini–mini, can be exemplified by a policy of increasing the visibility of infrastructure (internal weaknesses) and fighting corruption (external threat).

3. International Private Participation

In this section, the experience of PSP in the water sector and, particularly, in stormwater management is presented for six countries. Cases studies of the USA, China, Portugal, Argentina, Germany, and Australia are discussed and the main lessons are displayed. The next section will focus on the Brazilian experience.

3.1. USA—Stormwater Utilities and PPPs

In the USA, best management practices (BMPs) are generally adopted under the low impact development (LID) approach and diffuse pollution from urban stormwater is a permanent source of concern as it threatens the quality of receiving bodies [

17].

Federal regulations for municipal separated systems (MS4s) have been in place since 1990 as part of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to reduce sediment and pollutant loads from urban areas, but in Phase II, which covers municipalities with smaller populations (<100,000 inhabitants), drainage plans are ineffective and stakeholders have little involvement [

18].

The main challenge is the control of diffuse sources of pollution using the local authority which has very little control over private properties that are responsible for a large proportion of the sources of stormwater runoff. In addition, the management task is made more complex by limited financial resources and the lack of recognition by the community that drainage and stormwater management are public services and should be understood as such, similarly to water supply and waste collection, and therefore should have sources of funding such as taxes and tariffs that are accepted by all.

The lack of resources means that two alternatives are sought, the first through new taxes and subsidies and the second through the creation of stormwater utilities that can charge fees for services and use market mechanisms (e.g., discounts on tariffs for infiltration into lots for certain volumes) that encourage property owners to adopt stormwater management practices, even if these do not always abate pollution.

In Washington, D.C., a market has been created for stormwater credits that are generated concerning the reduction in stormwater runoff on properties. These credits can be traded in an open market where buyers need to meet regulatory requirements or, alternatively, they can be purchased by the Department of Energy and Environment, guaranteeing owners a return on their investment and providing private investment in certain areas of interest to society. At the same time, this stimulates the search for locations to install infrastructure with lower costs.

In a report concerning the responses of the participants of a stormwater utility survey [

19] about public–private partnership (PPP) models, 50% of the responses indicated that the use of PPP arrangements was dedicated exclusively to the design, construction, and rehabilitation of traditional infrastructures under new concepts of BMP.

The main management activities included in the annual budgets are related to operation and maintenance, and all issues show percentages of stormwater utility responses above 82%, except for the maintenance of combined systems (66%) and street sweeping (66%). The low number of responses in these two issues, however, is due to the fact that there are no combined systems in most of the participating municipalities and that street sweeping is usually linked to other municipal departments, although it is understood that there is a connection between sweeping and drainage. One aspect to be highlighted is the inclusion of public education as the second most mentioned issue (92%) in the responses.

3.2. China—Sponge Cities Initiative (SCI) and PPPs

China is the country with more experience in PPP arrangements [

20], having grown greatly since 2014 with the development of infrastructure projects promoted by the central government. By 2019, 8031 PPP projects were assessed as viable by the Ministry of Finance, with approximate investments of about USD 1.8 trillion in January 2020, but there is no specific law regulating and supervising projects regarding PPP options [

21]. The Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development did, however, produce a manual in 2014 that follows LID principles called the “Technical Guidance on Sponge City Construction” [

22].

With the growing concern over the flooding caused by rainfall events occurring in several major cities such as Shanghai, Wuhan (2016), Shenzhen, and the capital Beijing itself (2012), the Chinese government has adopted a series of policies and programs regarding drainage systems in cities, the most significant being the national initiative called Sponge Cities (SCI) that was announced in 2014. This is a flood management strategy focusing on the environment and ecosystems with the purpose rearranging the ongoing urban development process, taking into account the urban water cycle [

23].

Figure 3 presents the distribution of fifteen of the thirty cities chosen as pilots for the SCI and indicates the average annual precipitation (mm) [

24]. The initial budget estimated about USD 1 billion for each one, plus investments from local governments and the private sector.

China, similarly to any country with large territorial areas, such as Brazil, the USA, Russia, Canada, India, and Australia, has a wide variety of geographic and climatic settings. Thus, considering cities with complex climates such as Beijing, located in the north of China in a semi-arid and semi-humid region where there are problems of both water excess and the scarcity of water, sponge infrastructures should take care of storing rainwater to reuse it in times of drought. In the city of Wuhan, for example, located in southern China, the rainfall is greater than 1000 mm and soils are often in a saturated condition, requiring the interconnection of traditional systems (modernizing them) with sponge systems. This demonstrates the need for distinct, specific solutions in each city. About 45% of the cities suffer from insufficient water supply and 17% from total lack of water, and of the 32 metropolitan regions with more than one million inhabitants, 30 face difficulties in meeting their demands [

23].

This great existing diversity, however, can be taken as an advantage as long as there is an exchange of experiences among the pilot cities, not only from China, but also from other countries where the solutions may be applied, but this requires costly learning methods to be stored and constantly updated.

Regarding the attractiveness of private financial resources, the development of business models depends on information and estimates of costs and benefits of sponge city projects compared with the costs of traditional systems, which in China have accumulated rich experience due to the recent exponential growth of the country, including the application of modern technologies. This know-how is a factor that weighs in favor of traditional systems, considering that sponge cities, in contrast, are recent and still bring transaction costs such as integration between sectors, scope and learning, and execution time.

Many of the advantages of adopting the SCI are due to economic efficiency gains from benefits arising not only from economic gains, but from other multiple social and environmental aspects which are not so easy to quantify, and from the interconnection of investment agendas with other sectors. All these factors are aspects that should be taken into account when designing a business model that can be attractive to private initiatives [

23].

The forecast of the subsidies made by the Chinese government’s Ministry of Finance for the 30 pilot cities is USD 60 to USD 90 million per year for each city during the first three years. The first group of 16 pilot cities is expected to receive investments of USD 13 billion during the first three years for an estimated total construction of 450 km

2, which translates to USD 29 million per km

2. According to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), to achieve the planned amounts, the government encourages private participation through innovative arrangements such as PPP arrangements [

23].

Regarding society’s perceptions and knowledge about SCI, such as its willingness to support the initiative through the payment of additional amounts in water tariffs or the purchase of government-issued bonds (3.9% return annual rate), a public opinion survey was conducted in 2016 in the cities of Zibo (4.61 Mhab) and Dongyingn (2.09 Mhab) in Shandong province, one of the most important and industrialized provinces in China (third in terms of GDP and second in population) that is subject to rapid urbanization and has frequent problems with water supply and urban flooding [

22].

The results showed knowledge of the SCI and its objectives and the perception that subsidies and PPP arrangements are the main forms of financing the initiative; furthermore, respondents accepted the idea of a 17% increase in water prices to finance the construction of sponge cities. However, concerning investments, responses showed a willingness to spend, with the acquisition of SCI-related bonds, on average up to 55% of their annual surplus income. China, therefore, emerges with a bold current vision for private investment and participation in the stormwater sector.

3.3. Portugal—A Hybrid Model on the Right Track

In Portugal, the responsibility for stormwater management lies with the municipalities, which can delegate their operation to management entities through a specific contract. However, as there are two types of infrastructure systems—separate and combined—the former can be managed by two different entities, i.e., one for wastewater and the other for stormwater, although this may mean a loss of scale compared to the joint management that occurs in most systems, which are combined.

Decree-Law no. 194/2009 allows for joint management, although it does not clarify the form of cost recovery, and tariffs are subject to the approval of the Water and Waste Services Regulatory Authority (ERSAR).

In the discussion of the Strategic Plan for the Water Supply and Wastewater and Stormwater Management Sector 2030 (PENSAARP 2030), it was considered to make stormwater management a responsibility of the wastewater services —and thereby removing it from the duties and responsibilities of the municipalities. Currently, the services are provided by the municipalities themselves, by municipal companies, or by concessionaires, and may be attached to urban cleaning services.

However, whatever the form of management, one issue is the determination of the upstream and downstream boundaries of stormwater systems, with various types of consequences, such as the maintenance of urban cleaning (the cleaning of gutters, drains, watercourses, and beaches).

Currently, even though municipal water companies have legal status under private law, what is also being discussed is the feasibility of giving water customers a fourth service on their bill related to rainwater, in addition to water supply, wastewater, and solid waste, and the repercussion on the capacity of customers’ budgets and the budgetary burden for water services [

25].

The issue of resources to be invested—as demonstrated by the investment budget of the Lisbon General Drainage Plan (PGDL) 2016–2030 which, for fifteen years, reached the figure of EUR 250 million (only the cadastral survey, completed in 2020, had a budget of EUR 1.7 million)—raises the question of what is the best way to provide resources to finance actions.

Thus, PSP in stormwater drainage and management services in Portugal still has a long way to go and will require the definition of several issues, including the participation and sharing of obligations in society, some of which have been raised in this text.

3.4. Argentina—The Privatization Experience

The private concession of the WSS carried out in the metropolitan region of Buenos Aires presents aspects related to integrated water management that explicitly demonstrate the interrelationship between surface water (including stormwater) and groundwater. The region is located on the banks of the Rio de la Plata, a practically inexhaustible source of surface water, and at the same time is located up a system of underground aquifers of which the hydraulically connected Pampeano and Puelches aquifers are part [

26]. These groundwater aquifers are water tables from a few centimeters to 5 m below ground level and extend up to 60–70 m in depth, suffering from overexploitation [

27].

Despite the existence of aquifers with good quality water, the concession only provided for the use of surface water, also of good quality, disregarding the possibility that the poorest areas could be supplied by groundwater through the drilling of wells. Although it was accepted that this could happen, the concessionaire of Aguas Argentinas SA (ASSA) from the Suez Group did not carry out work in areas that did not have access to surface water.

The initial proposal provided for the service of the entire population without any conditions—that is, the universalization of the WSS regardless of the purchasing power, ownership, and infrastructure of housing—until the end of the term of the concession contract (thirty years).

It should be noted here that issues of ownership, housing infrastructure, and the provision of public services—which in the period before the concession were dealt with only between the municipality and the residents—now have a new entity: the private company. The recognition of property rights and the right to access the WSS are two interconnected processes, and privatization carries conflicting aspects such as, for example, the resistance to paying concessionaires for connections to the network—which are up to USD 400 to 600 for water and USD 1000 for sewage [

28]—by customers who do not own legal lots and are unsure of their permanence in the place. This is a matter handled by the government.

Universalization through the privatization of services encounters difficulties related to the urban planning processes of cities, especially in their poorest neighborhoods, which are exactly where the greatest deficits in the provision of the WSS are found. The greatest deficits in land regularization and the infrastructures of stormwater drainage are important parts of the system.

In the specific case of Buenos Aires, 25% of areas covered by the concession comprise a poor population (2 million people), making these issues very important.

From the late 1990s onwards, another relevant aspect regarding drainage, especially in the case of the metropolitan region of Buenos Aires, was the rise in the water table due to the closure of underground extraction wells due to the decrease in industrial activity, and also the contractual policy of using a single source of supply for surface water, plus the option of expanding networks with a relatively small increase in the sewage system and a great increase in the supply network [

28].

The rise in the low level of the water table caused a decrease in the infiltration capacity of the land and an increase in the number of supply networks without the counterpart of sewage, which caused less water to flow out than enter the region. Thus, especially in moments of high water levels in Rio de la Plata, urban flooding occurs. The population’s perception of the connection between these flood events and the “single source” contractual policy with little drainage has created consequent dissatisfaction. This is a factor considered as one of the causes for the failure of the concession contract to the private sector.

The first water services concession contract was signed in 1993, immediately before the 1994 constitutional reform, and the Suez Group announced its intention to disengage from participation in Aguas Argentinas S.A. in September 2005.

The lessons taken from the Buenos Aires experience reveal that not considering all aspects involved in urban water issues, in particular stormwater management, can jeopardize the feasibility of universalizing the WSS.

3.5. Germany—Participation of Landowners in Berlin

In new neighborhoods and subdivisions, it is possible to implement decentralized urban drainage management by installing devices on lots, and municipalities can make their own choices for decentralized drainage policies. However, in older neighborhoods with traditional (centralized) urban infrastructure already in place, carrying out required incentives depends on instruments that are generally supported by legislation and local rules, leading owners to adopt them.

Research conducted in Germany in 44 municipalities addressed the incentives for owners to adhere to decentralized management and, from the point of view of the New Institutional Economics theory, two institutional aspects of the municipal management of urban drainage present in all municipalities were analyzed: the first was the compulsory connection and use of existing networks, and the second was the taxes (from EUR 0.29/m

2 to EUR 1.93/m

2 with the unweighted average of the sample equal to EUR 0.85/m

2) and discounts applied. The analysis took into account the interaction between institutions (interplay) and contradictions with the refinancing of the existing infrastructure, as well as the risk of the loss of controllability due to the large number of people involved in management [

29].

In Germany, various mechanisms can be used to encourage the adoption of decentralization measures, and among these various other institutional aspects of municipal urban drainage management, such as land use planning, the mandatory use of green roofs, local funding programs, information campaigns, and restrictions on the use of centralized systems have been implemented.

Ideally, the design of the institutions should be conducive to the achievement of the objectives, i.e., to urge private owners to participate in urban drainage management, thus contributing to the municipality achieving its objectives, including better urban flood control and lower drainage infrastructure costs.

Figure 4 shows two previous planning stages, the objectives and integration strategies of the owners before the design of the institutions, and the two institutions under study, with the first being the compulsory connection and use of the networks, and the second the taxation of drainage systems. Furthermore, the interaction between the two institutions (the institutional interplay), the conditions for their adoption and operation, and the owners’ investment decisions harmonized with the objectives and strategies previously planned are presented.

Two decentralization strategies (integration of landowners into stormwater management) can be implemented; landowners are more likely to adhere to decentralization with higher fees and discounts. There are two other strategies that are considered to exclude landowners in management. Thus, there are four different institutional conceptions: forced decentralization and selective decentralization (more inclusive of private participation by property owners in management) or, alternatively, an extension of the public network and maintenance of the status quo (more exclusive of private participation).

In the first case, for forced decentralization, there is no compulsory connection, the fees are high, and many discounts are offered. The option is favorable to municipalities that are highly dependent on the contribution of property owners for the protection of surface water for water balance and flood protection, and where a high potential for conflict over refinancing and a significant loss of control are accepted.

In the second case—selective decentralization—there is no compulsory connection, high fees, and no rebates. This concept promotes the protection of surface water against flooding with the water balance receiving support from landowners, and may be the option for municipalities that accept high risks related to refinancing and loss of controllability.

The third case—guaranteeing the extension of the public network—combines compulsory connection with high fees and no rebates, and can be chosen when it is desired that the owners contribute by co-financing the public system while maintaining a low refinancing risk and no loss of controllability.

The fourth option—status quo—is a combination of compulsory connection, a low level of taxation, no special rebates, minimizing incentives for owners to decentralize, creating long-term controllability, and ensuring no refinancing conflict. This is a good choice for municipalities where small charges can be supported to achieve the objectives of stormwater management.

Taxes are usually used to finance existing systems under the vision of cost recovery, which can lead to high taxes according to the needs of these systems. Thus, policies of incentives to decentralize through discounts can lead to a certain number of disconnections from the network with a loss of revenue, but also a decrease in demand. On the other hand, the lower the charges and the lower the incentives for disconnection, the greater the possibility of maintaining the status quo, that is, of the systems requiring ever greater resources.

Using a geographical information system (GIS), it was found that even in densely populated areas of Berlin, it was easily possible to disconnect 30% of the impervious areas in a 22 km

2 catchment area with a separate sewerage system [

30].

Taxes have an ambiguous role as both a source of revenue for the refinancing of existing public systems and a source of incentive for the decentralization of the systems, which also makes them a source of revenue loss due to possible disconnection.

From an economic point of view, there are arguments against decentralization, such as the devaluation of investments already made and the risk of growth in costs and charges, combined with the loss of economies of scale and high transaction costs [

29].

Despite its advantages, the issue brings complexity by requiring the determination of the balance between the values of charges, the needs of existing systems, discounts for disconnections as incentives for owners, and the risk of loss of control over the management of the systems due to the greater number of participants.

3.6. Australia—Water Markets

In Australia, the water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) concept is widespread and separative systems have been implemented, but there is still a need to expand the knowledge of stormwater resource use within the urban water cycle, creating the possibility for more effective economic and business plans. Concerning private participation through charging, the example of Melbourne can be cited, which in 2016 received AUD 6645/Kg per year for stormwater nitrogen loading [

31].

In Melbourne, economic aspects had a strong influence on the private solutions adopted, such as PPP arrangements for large projects. They also acted as an incentive to build an additional private network for a recycled wastewater supply. The existence of funding for the installation of rainwater tanks as an alternative source of non-potable water was also used as an incentive for the adoption of the solution [

32].

The creation of a market for the transaction of water access and use rights, called the Water Market, was conceived in Australia as a way to address, especially in times of scarcity, a better balance of use in rural areas. However, despite the political and institutional constraints to its use in transactions between rural and urban areas, Adelaide, Bendigo, and Ballarat have used this mechanism to circumvent urban scarcity problems [

33].

4. Brazil

Brazil has a long history of reactive actions to public service delivery issues with very little planning. Here, we focus on the specific aspects. Several issues contribute to this, such as the frequent change in political direction after elections; the reduced knowledge and participation of the population; the lack of institutionalization and organization of specific administrative structures; regulations being in infancy; corruption, diversion, and the poor allocation of resources; lack of prioritization; lack of political will; and the poor teaching of current drainage techniques, among many others, that may occur simultaneously or not [

11].

Despite this terrible picture, several initiatives continue to be tried and deserve attention, and we will look at them to try to extract good examples for the evolution of the stormwater management debate.

4.1. São Paulo

In Brazil, there is a multiplicity of actions regarding urban stormwater drainage and management, especially in large municipalities, the most populous among them being the city of São Paulo. This metropolis opted, like 665 other municipalities, according to the Basic Sanitation National Plan (PNSB) of 2008 [

34], for the construction of several temporary rainwater detention reservoirs as a way to attenuate the precipitation peaks and volumes in the municipal region.

In this municipality, PSP was considered in one of the last actions of 2020 through a PPP arrangement in the modality of administrative concession, i.e., the main payments to the concessionaire would be made directly by the municipality, additionally allowing the latter to obtain ancillary revenues. In this specific case, such revenues would come from the commercial exploitation of air spaces located above four existing stormwater detention and retention reservoirs (Sharp, Guaraú, Anhanguera, and Rincão). The main objective of the contract was the requalification, operation, maintenance, and conservation of the four existing reservoirs, as well as drainage interventions for the five micro basins of the municipality. The total expected value is USD 257 million over the 33-year term of the contract [

35].

Only by way of comparison, according to the recent Basic Sanitation National Plan (PLANSAB) of 2013, the estimates of resources to be spent on urban drainage in Brazil by region are presented in

Table 1.

4.2. Brasília—Federal District

In Brasilia, the federal capital of Brazil, located in the Federal District (DF), the responsibility for the provision of urban stormwater drainage and management services lies with the Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (NOVACAP), according to District Law no. 4.285/2008 (arts. 51 and 52). Article 51 states that NOVACAP will be granted a concession contract with the Federal District’s Water, Power and Sanitation Regulatory Agency (ADASA) for thirty years, renewable for up to twenty years at the discretion of the executive power, and that a PPP contract will be signed to make the services economically viable.

When the legislator present in the law affirms the intention of seeking the economic viability of services through the forecast of PPP arrangements (Article 51), and charging (Article 53) indicates the intention of PSP, that has, as will be seen further on, not prospered (at least up to now), this characterizes a case of mimetic isomorphism—in other words, the copy of an existing model in operation in other contexts, but without its effective placement in practice. It is thus a contradictory situation between “de jure” and “de facto”, as pointed out by some authors [

36].

NOVACAP, a public company, however, is not a specialized body for this activity and disputes tax revenues for many other purposes. Furthermore, the concession contract envisaged in Article 51 of the law, according to part of the doctrine, brings contradictions since the NOVACAP company cannot be treated as a concessionaire since it is a political entity holding a public service, and perhaps this is why such a contract was not signed [

37].

Besides NOVACAP, the Department of Highways (DER) is also in charge of urban drainage, since several highways cross the urban areas of the Federal District requiring the management of the interface between these agencies.

The economic and financial sustainability of these services, according to the same law (District Law no. 4.285/2008, Article 43) provides collection in the form of taxes, following the regime of the provision of services and their activities. However, more than ten years later this has not yet been implemented, making it difficult to face the issues posed by the Urban Drainage Master Plan (PDDU) and confirmed by the District Plan of Basic Sanitation (PDSB) of the Federal District (DF 2017).

Article 53 of the same law (District Law no. 4.285/2008) provides charged public services for the drainage and management of urban rainwater taking into account, in each lot, the percentages of impermeable areas and the existence of rainwater damping and retention devices, in addition to other criteria such as income level of the population of the served area, the characteristics of the urban lots, the areas that can be built on them, and the effective drainage area in the case of completed construction, evaluated according to technical criteria established by ADASA. However, the executive power has not yet taken any initiative to implement the charge.

Despite the absence of a specialized body to provide services and a specific source of resources for the financial support of the activity, ADASA has been carrying out several important actions to organize the sector.

Such actions include the elaboration of a drainage and stormwater management manual and the monitoring of the elaboration of the PDSB that identified the need for institutional development and infrastructure deficits. A review of the DF drainage system cadaster was also made, in addition to GIS development, the proposition of control of sediment generation by civil construction works incorporated in the new DF Works and the Buildings Code, and guidelines for public works.

Another work performed by ADASA was the assessment of the extent and composition of the DF’s public and private sealed areas through high-resolution images, as summarized in

Table 2. Finally, the identification of options for the institutionalization of service provision, including the feasibility and legality of charging, modeling the charging structure involving sealed areas, social tariffs, cross-subsidies, and other parameters for the assessment of annualized reference costs to be covered, was completed [

37].

Table 2 shows that private impervious areas are approximately equivalent to public areas, suggesting the possibility of the joint participation of the public and private sectors in the revenues to support the economic and financial management of stormwater drainage and management services in the Federal District.

5. Results and Discussion

The objective of attracting private capital requires solid strategies based on a vision of consolidated social interests and priorities clearly expressed not only in general public policies that have attractiveness as one of their objectives, but also in specific public policies that, for example, determine the priority areas of action, as seen in China, where pilot projects were concentrated in 30 cities. It was, however, the problem of floods and water scarcity that pushed action in the direction of Chinese sponge cities [

38].

Table 3 shows the main pros/cons and barriers.

From climatological and hydrological mapping combined with historical occurrences and the existing infrastructure in each place, one can have a starting point for determining these priorities. This alone, however, is not enough, as there remains the issue of quantifying the resources needed for the actions. This quantification requires knowledge of the cadasters and the updated situation of the infrastructure, in addition the dimensions of events with several return times and the respective associated costs. The determination of the technical structures (human and material resources) on which the responsibility and deadlines should fall to accomplish the tasks mentioned above passes through the existence (or construction) of these structures, and also the “rules of the game”, for this to happen.

In large countries such as Brazil, China, and India, prioritization is part of the game, despite the importance of building national guidelines. However, prioritization requires knowledge of the problem and strategies for action, i.e., data, information, and planning, without which there is no business management towards solutions.

However, with a passive policy in the face of reality, in the simple expectation that municipalities can formulate their demands for the supply of resources from the central government, as it has been happening in Brazil, an undesirable selectivity of municipalities occurs without achieving the objectives for the application of available resources, nor the control and solution of the problems of flooding in the places where they are most critical. The choice for the allocation of resources based only on the existence of projects that comply with legal accounting rules results in actions centered on municipalities that do not necessarily keep close correlation with the priorities and problems focused on by pro-active policies, which aim to solve them and present results in well-defined time horizons.

The attractiveness of private capital must overcome this bureaucratic–technical frontier for the allocation of public resources and focus on the solution of problems without the restrictions required by the resources of public budgets, that is, the solutions must be the responsibility of the private capital, especially for its economic sustainability, making use of accounting by showing the expenses and revenues of the projects from a perspective more linked to project finance than to subsidies and governmental contributions, even if this requires extending the life of the projects.

In Brazil, the scarcity of resources in public budgets finally led to escape from the trap of the controversial debate between forms of capital (public or private) to be applied in solving problems related to the WSS, especially the issue of universalization. By opting for private capital and an increase in PSP, the need for its regulation was verified and thus depends now on the elaboration of rules for regulation through a specific agency [

39]. However, as a centralized decision solution, defined from top to bottom without any participation of society, there is the risk of practicing a kind of mimetic isomorphism and at the same time forgetting the complexity of the sector, especially the local aspects, which are particularly expressive concerning stormwater management, and reaching questionable results.

Drainage pricing in almost all charging initiatives is vital to sustaining programs, as is the case in the USA, which has proven sensitive to public understanding and support than when it comes to water supply and wastewater runoff. In Brazil, this should be similar and they should encounter barriers with the adoption of top-down solutions. Of all the sub-national regulatory agencies, only one (ADASA) has tackled the issue of drainage regulation, however, without addressing pricing issues.

Under this view, projects deserve to broaden their objectives and include systems other than just urban drainage and stormwater management. The concessions of areas such as zoos [

40], for instance, in which detention or infiltration basins can be included, may allow their financing in part through entrance fees and other revenues linked to the parks.

In the case of mapping, there is ample climatological documentation, which should, however, be permanently updated in light of climate change. In the case of Brazil, the National Sanitation Information System (SNIS) database deserves to be improved to apply the above vision.

In Brazil, the coordination of this information (climate, infrastructure, and feasible concessions) requires the participation of staff structures that include people and resources to format projects which, if successful, can serve as an example so that other cases can be executed. This takes time, and the implementation of this vision must urgently start so that know-how and private capital participation can contribute to urban stormwater management as soon as possible. In China, it is estimated that the experience should take a generation [

41].

6. Conclusions

Concerning PSP in urban drainage systems, there is a long way to go given the current situation, both in terms of independent organizational structures, cost segregation, and investments to be made. All, in turn, depend on political options, institutions, and management techniques such as, for example, the different policies of forms of use, e.g., resources, non-potable or potable, treatments, and decentralization, each with different applicable technologies (infiltration, aquifer recharge, green roofs, cisterns, disconnections, and impervious area removals). Through case studies in different countries, an overview of PSP in the drainage and stormwater system sector has been presented, seeking to present the reasons that underpin the importance of PSP, as well as the pros/cons and barriers to its implementation.

This study aimed to verify—based on the idea that PSP can bring important contributions to the public services sector with the main driving forces of attractiveness to capital and efficiency—how PSP has worked in practice, using urban stormwater management services as an object of study. A critical analysis of the relevant aspects found in several existing cases in four continents, but with a special focus on Brazil, was synthetically carried out, and characteristic aspects with the potential to be useful to reflection due to their singularities or similarities were presented.

The subject was approached in several ways, but brings greater focus on the economic aspects involved, which is a point of great relevance given the rise in the scarcity of public budgets, aging infrastructures, and climate and demographic change demands. The lack of a wider approach to the advantages and disadvantages involved in the other aspects can be considered one of the limitations of the work.

Finally, what is certain is the fact that within the urban water cycle, rainwater is becoming increasingly more important. Calling attention to its use leads us to demand the study not only of ways to use it, but also of the institutions and organizational structures involved in its management, as the existing and traditional ones are not adequate or attractive to private sectors. Thus, by utilizing this resource appropriately, the challenges of stormwater PSP will become just another summer dream.