Abstract

Water management and governance continues to rely on the scientific and engineering principles of the hydrologic cycle for decision-making on policies and infrastructure choices. This over-reliance on hydrologic-based, technocratic, command-and-control management and governance tends to discount and overlook the political, social, cultural, and economic factors that shape water-society relationships. This paper utilizes an alternative framework, the hydrosocial cycle, to analyze how water and society shape each other over time. In this paper, the hydrosocial framework is applied to stormwater management in the United States. Two hydrosocial case studies centered on rain and stormwater are investigated to highlight how stormwater management can benefit from a hydrosocial approach. The insights and implications from these case studies are then applied to stormwater management by formulating key questions that arise under the hydrosocial framework. These key questions are significant to progressing stormwater management to more sustainable, resilient, and equitable outcomes for environmental and public safety and health. This paper frames a conversation for incorporating the hydrosocial framework into stormwater management and demonstrates the need for an interdisciplinary approach to water management and governance issues.

1. Introduction

“The fundamental problem with conventional stormwater management may be the mindset. It does not treat water as a valuable resource but more like a problem to be solved, or even worse, it as a waste product” [1].

Water is a substance that is inextricably linked with life. It is a “non-substitutable flow resource essential for life and ecological health” but also “of deep spiritual and aesthetic significance” [2]. Water and society are deeply connected with water leaving a trace of its historical, political, and social influence on society as it flows over the landscape [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The “social nature” of water is the idea that water’s materiality, conceptual significance, and meaning is the direct result of the social relations that produce it [10]. Social nature reflects Cronon’s ideas where, “what we mean when we use the word ‘nature’ says as much about ourselves as about the things we label with that word” [11]. What people mean when they talk about water, the different names, meanings, and values they place on water are created by socio-natural processes. These socio-natural processes being the internal relations that materially and discursively shape water and society, blurring and abstracting the separation between the two [12].

The idea that water is “inescapably social” [9] is in direct contrast with the preeminent Western epistemology where nature and society are separate entities. This dominant cultural ideology has allowed water to become an object of management, governance, and commodification. As a result, command-and-control practices and technocratic solutions dominate water management and are the primary mechanisms to control natural hydrologic processes [13,14,15,16]. These technocratic solutions struggle to reach resilient, sustainable, and equitable outcomes due to disregarding and overlooking the social nature of water [4,5,6]. Moving past the command-and-control, engineering-based model is essential to address the complex and wicked problems for a growing population and in an ever-changing climate [13,14,17].

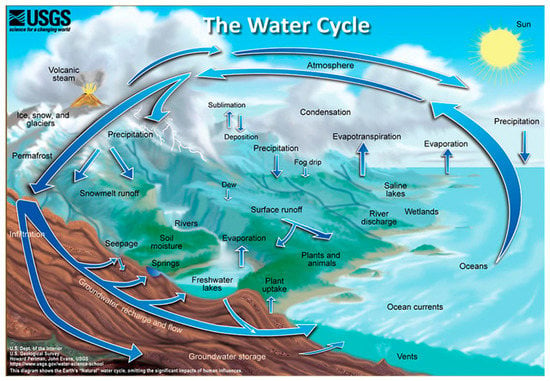

This desocialization and depoliticization of water management under the prevailing Western epistemology is extremely evident in stormwater management in the United States. Stormwater management has been a public health, public safety, and environmental issue throughout the history of mankind, exacerbated by the drastic increase in urbanization within the last century [18]. In the United States, stormwater management remains in a technocratic realm of engineers and hydrologist due to the separation of humans from the hydrologic cycle. The majority of stormwater management and governance decision-making is based solely on hydrologic variables and analyses, rather than utilizing more holistic approaches [15,17,19,20,21].

Despite this, there has been progress towards more resilient stormwater management—from solely flood control towards treating stormwater prior to release into surrounding waterways. One example of this progress is the utilization of green infrastructure, rather than traditional grey infrastructure, to help manage stormwater volume and quality in urban and suburban areas [13]. Currently though, stormwater management in the United States continues to struggle with changing climatic conditions while maintaining human and environmental well-being [13,14,17]. Many urban water and stormwater management scholars suggest that climate change requires a complete rethinking and overhaul of water management, including stormwater management, especially in urban areas [14,22]. This rethinking of water management parallels the development of the concept of nature-based solutions to urban environmental challenges. Nature-based solutions are ecosystem-based approaches to environmental management that may provide resilient solutions to climate adaptation and mitigation that addresses biophysical, social, and political challenges of implementation and planning [23,24].

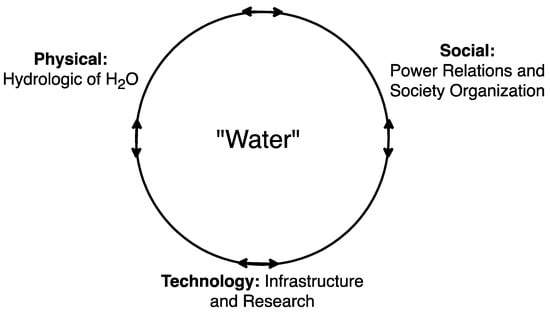

Most engineers, hydrologist, and ecologists alike acknowledge that understanding the social, political, and economic factors driving stormwater management is important, but typically, these factors are discounted and not incorporated into decision-making and governance [17,20]. One approach that can help bring these factors into decision-making is the hydrosocial framework, which stresses that water and society exist in an integrated system. So, rather than people affecting hydrologic systems from the outside, the hydrosocial cycle views water and people as an integrated system with internal connections between humans and water [3]. The hydrosocial cycle as a framework for stormwater management can provide the ability to assess and understand the political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions. The hydrosocial cycle promotes a critical analysis of water-society relationships, positioning humans within the hydrologic cycle, where humans and water co-construct themselves based upon complex interactions of social, political, historical, economic, and hydrological factors.

The goal of this article is to explore how the hydrosocial cycle, as a framework for analysis, can provide the platform to investigate the social and natural relations of stormwater. We begin by showing that a hydrological framework that does not integrate the socio-natural aspects of water and stormwater heavily influences most stormwater management thinking and programs. Next, we present details of two case studies to illustrate the application of the hydrosocial cycle through which broader cultural, social, and political factors are linked to water management, in one case rainwater harvesting and the other stormwater management. The insights and lessons learned from these two different case studies are useful and suggestive to what a hydrosocial approach to stormwater management might look like or consider. Finally, we suggest some implications and provide recommendations focused on how hydrosocial analysis of stormwater management can increase the understanding of the socio-natural aspects of stormwater and how stormwater engineers and managers can begin to think within a hydrosocial framework.

2. History of Stormwater Management in the United States

Stormwater management is not a modern invention in response to urbanization. Ancient civilizations, like the Romans and Mesopotamians, constructed rather sophisticated water drainage infrastructure throughout their cities [25]. Historically, “pave and pipe approaches” were used to move stormwater off the landscape as quickly as possible with a “slow and soak” approach being utilized currently where stormwater is slowed down and allowed to remain and soak into the landscape over a longer period of time [18]. As populations continue to grow within the United States and throughout the world, a larger proportion of the landscape will be developed into suburban and urban environments. Development of the landscape can have a drastic effect on stormwater hydrology through a host of mechanisms, including removal of vegetation, compaction of soils, and construction of impervious surfaces [17]. The processes of development significantly reduce the ability of the landscape to maintain proper hydrologic functioning [26,27,28,29,30,31]. As urbanization has continued and the construction of impervious surfaces increased, it has become glaringly evident that stormwater management is necessary to maintain public and environmental health.

The concept of a hydrosocial contract or unwritten contract between society and their government to provide potable drinking water, water sanitation, management of stormwater, and flood protection begins to highlight how society and water have co-evolved over time [32]. This co-evolution can be seen in changes in the hydrosocial contract, especially through the outcomes and goals of stormwater management. Stormwater management in the United States has undergone transitions; however, these transitions has been slow and ineffective at responding to the changing conditions and delivering management outcomes that align with the public and environmental concerns posed by stormwater [13,17,20]. Stormwater management began in urban areas with the primary goal of protecting public health from waterborne diseases that were prevalent due to the dumping of human waste into surrounding waterways. To combat this, some urban areas constructed combined wastewater and stormwater pipes, which transmitted stormwater and wastewater to a central water treatment plant before release into local waterways. These combined sewers work well during dry conditions, but during wet weather, these combined sewers overflow resulting in the direct release of untreated sewage and stormwater directly into surrounding waterways [33]. Additionally, public safety became a primary concern due to flooding resulting from a host of landscape alterations associated with urbanization. To provide flood protection, the dominant view has been to transport stormwater off the landscape as quickly as possible, resulting in the technocratic solution of concrete lining or placing of streams into pipes to expedite the movement of stormwater to larger, receiving bodies of water. This paradigm in stormwater management, characterized primarily by the expedited movement of stormwater off the landscape and into receiving bodies of water, have been called “drained or sewered cities” [13,14].

This paradigm dominated until the beginning of the environmental movement, where society wished to rethink the hydrosocial contract, leading to the subsequent passing of the Clean Water Act (CWA) in the 1970s [17,19]. The passing of the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the subsequent amendments (301 and 402) in 1987 placed legal requirements on state and local governments to control and treat stormwater prior to release into waterways [18]. These policies caused a distinct shift in stormwater management towards stormwater control measures that not only managed the volume, but also the quality of stormwater. Cities and municipalities have aligned with these legal requirements following both traditional grey infrastructure (centralized conveyance systems and water treatment plants) and green infrastructure (GI) (decentralized infiltration systems and practices) with the implementation of either varying spatially or temporally [17,18,19]. Stormwater management during this era has been called “waterways cities” [13], where the primary goal of stormwater management is to reduce pollutants entering waterways via stormwater through water volume reduction and water quality improvement practices. This is the current paradigm in the United States, but with a vast spectrum of implementation both within cities and throughout the country. Some cities have invested greatly in decentralized GI while others have continued to rely on grey infrastructure to meet the requirement of the CWA, but the large majority have implemented a complex combination of both grey and GI [34].

While there is agreement that decentralized GI practices will promote more sustainable and resilient stormwater management, the adoption and implementation of these practices has been slow mostly due to social, economic, and political factors [19,20,21]. Engineers, hydrologists, and ecologists who often make stormwater infrastructure and management decisions frequently overlook these factors [17,20]. This tends to result in the implementation of traditional grey infrastructure rather the adoption of new, GI practices. To compound these issues, climate change has prompted scholars to suggest that a “complete reworking of urban water governance” [35,36] is required to cope with the public health, public safety, and environmental issues. In the United States, stormwater management must adapt to the changing climate, population growth, and increased urbanization towards more resilient, sustainable, and equitable outcomes. This would require stormwater management to incorporate the socio-natural aspects of stormwater into management and governance decision-making. This would also require a conceptual shift away from the hydrologic cycle and towards understanding of stormwater and society more holistically—this transition can be done using the hydrosocial cycle.

7. Conclusions

Many ecologists and engineers suggest that the technology to achieve more sustainable, resilient, and equitable water management in cities is available through stormwater GI, low-impact development, and best management practices [17,20]. However, they understand that implementing these technologies is relatively futile without social, political, and economic acceptance and support [34,42,45,46]. Hydrosocial research provides the foundation to increase the successful implementation of stormwater management technologies and practices within a diverse range of hydrosocial configurations. Natural and social scientists alike can utilize the hydrosocial cycle, bringing stormwater management out from behind the technocratic shroud of the hydrologic cycle and past the nature-society dualistic relationship.

Stormwater provides the basis to understand, more broadly, urban life and inequity through a hydrosocial framework. For hydrosocial researchers, stormwater is a medium within water–society relationships that has immense research potential, specifically for improving the resiliency, sustainability, and equity of stormwater management in the United States. Stormwater provides an excellent platform to see how application of the insights and implications from research can be utilized for meaningful and relevant changes to stormwater management outcomes [47]. Stormwater managers often encounter political, social, and economic obstacles, which are difficult to address when attempting to provide the best stormwater management outcomes for public and environmental health. The hydrosocial cycle provides the foundation to place ecohydrologic research into the a more holistic setting, promoting reflexivity in research, framing advances in technologies or management within the appropriate and necessary social, political, and economic climates.

Stormwater and the management of stormwater is highly cultural, social, and political in nature and only through incorporation of these factors into management decision-making and governance, can a transition towards more sustainable, resilient, and equitable stormwater management be reached. It is suggested here that in the short-term, hydrosocial analyses on stormwater management will be necessary in promoting a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable stormwater management paradigm. Ultimately, the hope is that stormwater will become an environmental flow within the hydrosocial cycle assessed, understood, and managed by engineers, ecologists, hydrologists, political ecologists, economists, and geographers alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W.; Methodology, M.W.; Investigation, M.W.; Writing—Original draft preparation, M.W.; Review and Editing, M.P.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by NSF-CNH/AGS no. 1518376 and a USDA NIFA Hatch project through the Maryland Agricultural Experimentation Station.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful for the guidance and mentorship provided by Michael Paolisso throughout the conceptualization, investigation, writing, and editing of this paper. Additionally, we would like to thank Sarah Ponte Cabral, Amanda Rockler, and Marissa Mastler for their edits and reviews throughout the writing process. Finally, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for improving the quality and extending the scope of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karvonen, A. Politics of Urban Runoff: Nature, Technology, and the Sustainable City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Water: Political, biopolitical, material. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2012, 42, 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, J. What Is Water? The History of a Modern Abstraction; Carelton University: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, J.; Budds, J. The hydrosocial cycle: Defining and mobilizing a relational-dialectical approach to water. Geoforum 2014, 57, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budds, J.; Linton, J.; McDonnell, R. The hydrosocial cycle. Geoforum 2014, 57, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Budds, J. Whose scarcity? The hydrosocial cycle and the changing waterscape of La Ligua river basin, Chile. In Contentious Geographies, Environmental Knowledge, Meaning, Scale; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2008; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.J. Historicising the hydrosocial cycle. Water Altern. 2014, 7, 220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Durrenberger, E.P. The political ecology of ritual feasting. Res. Econ. Anthropol. 2008, 27, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N.; Braun, B. Social Nature; Blackwell Publishers: Malden, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 17, ISBN 0142-7849. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N.; Braun, B. (Eds.) Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millenium, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0203983963. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, W. Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature; W.W Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Maldonado, M. The anthropocenic turn: Theorizing sustainability in a postnatural age. Sustainability 2016, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.R.; Keath, N.; Wong, T.H.F. Urban water management in cities: Historical, current and future regimes. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.H.F.; Brown, R.R. The water sensitive city: Principles for practice. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, M.A.; Brown, R.R. Making the implicit, explicit: Time for renegotiating the urban water supply hydrosocial contract? Urban Water J. 2014, 11, 392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, B.C.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Brown, R.R. A strategic program for transitioning to a Water Sensitive City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 117, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, K.P.; Chevalier, L.R. Urban Stormwater Governance: The Need for a Paradigm Shift. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1112–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, L. Urban Stormwater Management in the United States; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, K.P.; Chevalier, L.R. Managing urban stormwater for urban sustainability: Barriers and policy solutions for green infrastructure application. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.H.; Wenger, S.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Walsh, C.J.; Ladson, A.R.; Shuster, W.D.; Thurston, H.W.; Brown, R.R. Impediments and solutions to sustainable, watershed-scale urban stormwater management: Lessons from Australia and the United States. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.R. Impediments to integrated urban stormwater management: The need for institutional reform. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.J. Of floods and droughts: The uneven politics of stormwater in Los Angeles. Polit. Geogr. 2017, 60, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N. Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 93, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.E.; Fernandes, J.N.; David, L.M. Key Issues for Sustainable Urban Stormwater Management. Water Res. 2012, 46, 6787–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.J.; Roy, A.H.; Feminella, J.W.; Cottingham, P.D.; Groffman, P.M.; Morgan, R.P., II. The urban stream syndrome: Current knowledge and the search for a cure Source. In Journal of the North American Benthological Society; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005; Volume 24, No. 3; pp. 706–723. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, D.M.; Walbridge, M.R. Best Management Practices for Nutrient and Sediment Retention in Urban Stormwater Runoff. J. Environ. Qual. 2007, 36, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, M.E. Low impact development practices: A review of current research and recommendations for future directions. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2007, 186, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.D.; McMillan, S.K.; Clinton, S.M.; Jefferson, A.J. Hydrologic response to stormwater control measures in urban watersheds. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizadeh, A.; Rippy, M.A.; Fletcher, T.D.; Feldman, D.L.; Peng, J.; Bowler, P.; Mehring, A.S.; Winfrey, B.K.; Vrugt, J.A.; Aghakouchak, A.; et al. From Rain Tanks to Catchments: Use of Low-Impact Development To Address Hydrologic Symptoms of the Urban Stream Syndrome. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11264–11280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, K.; McPhee, Z.; Bolisetti, T. Performance and implementation of low impact development—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, R.; Turton, A.R. The hydrosocial contract theory and the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. Water Policy 2003, 5, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.L. Spatial and temporal variation in local stormwater infrastructure use and stormwater management paradigms over the 20th century. Water (Switzerland) 2016, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cettner, A.; Ashley, R.; Hedström, A.; Viklander, M. Sustainable development and urban stormwater practice. Urban Water J. 2014, 11, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.J. Volume control: Stormwater and the politics of urban metabolism. Geoforum 2017, 85, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A.J.; Scobell, A. How China Sees America; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012; Volume 91. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, R.E. The field, scope, and status of the science of hydrology. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1931, 12, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.W.; Bishop, K.; Zarnetske, J.P.; Hannah, D.M.; Frei, R.J.; Minaudo, C.; Chapin, F.S.; Krause, S.; Conner, L.; Ellison, D.; et al. A water cycle for the Anthropocene. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 33, 3046–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radonic, L. Becoming with rainwater: A study of hydrosocial relations and subjectivity in a desert city. Econ. Anthropol. 2019, 6, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finewood, M.H. Green Infrastructure, Grey Epistemologies, and the Urban Political Ecology of Pittsburgh’s Water Governance. Antipode 2016, 48, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, K.M. Tool-power: Water infrastructure as wellsprings of state power. Geoforum 2014, 57, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Burns, M.J. Urban Stormwater Runoff: A New Class of Environmental Flow Problem. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.J. Structuring Hydrosocial Relations in Urban Water Governance. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finewood, M.H.; Matsler, A.M.; Zivkovich, J. Green Infrastructure and the Hidden Politics of Urban Stormwater Governance in a Postindustrial City. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, M.; Barroca, B.; Amdal, J.R.; Diab, Y.; Becue, V.; Serre, D. Analysing urban resilience through alternative stormwater management options: Application of the conceptual Spatial Decision Support System model at the neighbourhood scale. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgani, Y.T.; Yazdandoost, F.; Moghadam, M. Role of Resilience in Sustainable Urban Stormwater Management. J. Hydraul. Struct. 2013, 1, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wesselink, A.; Kooy, M.; Warner, J. Socio-hydrology and hydrosocial analysis: Toward dialogues across disciplines. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2017, 4, e1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).