1. Introduction

The term spatial planning should be understood as all techniques aimed at shaping the space in a way that ensures its order [

1] preceded by studies and analyses, based on scientific grounds, related to the location of objects in the adopted planning space [

2]. The activities related to spatial planning are associated with future conditions of this space, and they are undertaken by the relevant public authorities on the basis of the current status of development. Planning procedures are launched in order to [

3]:

shape the space in such a way as to form a harmonious whole and take into account all the considerations and functional, socio-economic, environmental, cultural as well as compositional and aesthetic requirements in structured relationships;

ensure socio-economic development, in which political, economic and social activities are integrated, maintaining natural balance and permanence of basic natural processes in order to guarantee a possibility to meet the basic needs of individual communities or citizens, of both the present generation and of the future generation;

implement actions, taking into account the objectified needs of the general public or local communities, associated with land development.

It should be remembered, however, that spatial planning procedures are not always carried out in a harmonious manner. It may be the case that different expectations as to the intended purpose of an area may lead to confrontational situations [

4]. These so-called spatial conflicts usually arise when the parties thereto have conflicting interests with respect to the manner in which a given area is to be used [

5].

As a result of the adoption of the Directive for establishing a framework for Maritime Spatial Planning by the European Parliament and the European Council, the problem of creating planning procedures has become a current issue; it would have resulted in land use plans for these areas. Since the European Community considered maritime areas to be extremely valuable, all the coastal countries of the European Union ought to create their own development plans for maritime areas before March 2021, and these plans should be developed within the framework of international cooperation [

6]. Importantly, this cooperation should be carried out based on the rules of territorial governance [

7]. These interactions ought to be understood as a set of formal and informal interactions that are allowed and conditioned by national spatial planning systems. In territorial management, both vertical relations (between policy levels) and horizontal ones (between policy sectors and between public/private operators) can be noticed.

Although the problem has already been tackled in scientific publications, i.e., [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], the European Union does not have much experience in this regard yet. The EU Member States are currently at various stages of creating procedures related to maritime spatial planning [

14], and experience in transboundary approaches is growing through official processes and pilot programs [

15]. Due to the fact that there mainly were pilot programs conducted, the aim of this study is to analyze the existing legal regulations and to assess the national procedures resulting therefrom.

The internal laws of the individual countries of the European Community differ from each other. It can be noticed, however, that maritime spatial planning borrows numerous methods from land planning [

16]. Although each EU Member State has a unique spatial planning system for land areas, it is possible to identify groups of countries that have similar approaches [

17], which is easily noticeable when analyzing the descriptions of spatial planning systems contained e.g., in [

18,

19,

20,

21]. That is the reason why this research paper narrows down the analysis of marine spatial planning to one country only. The Polish part of the Baltic Sea was selected as an example.

The research material includes both the provisions of the international and national laws. In addition, the statistical data on spatial planning procedures in areas of land and sea interaction have been analyzed. For the evaluation of the maritime spatial planning system, the SWOT/TOWS analysis has been used. The performed studies have been aimed at determining the directions of development of maritime spatial planning in Poland based on the current conditions of the spatial planning procedure for these areas as well as the future phenomena related to the implemented procedures for creating maritime area land use plans.

3. Materials Description

The research material includes the provisions both of the international and the national laws as well as statistical data on spatial planning in the areas of land and sea interaction. According to the authors, their detailed description will give the reader a broader perspective and enable better reception and understanding of the conclusions being part of the SWOT/TOWS analysis.

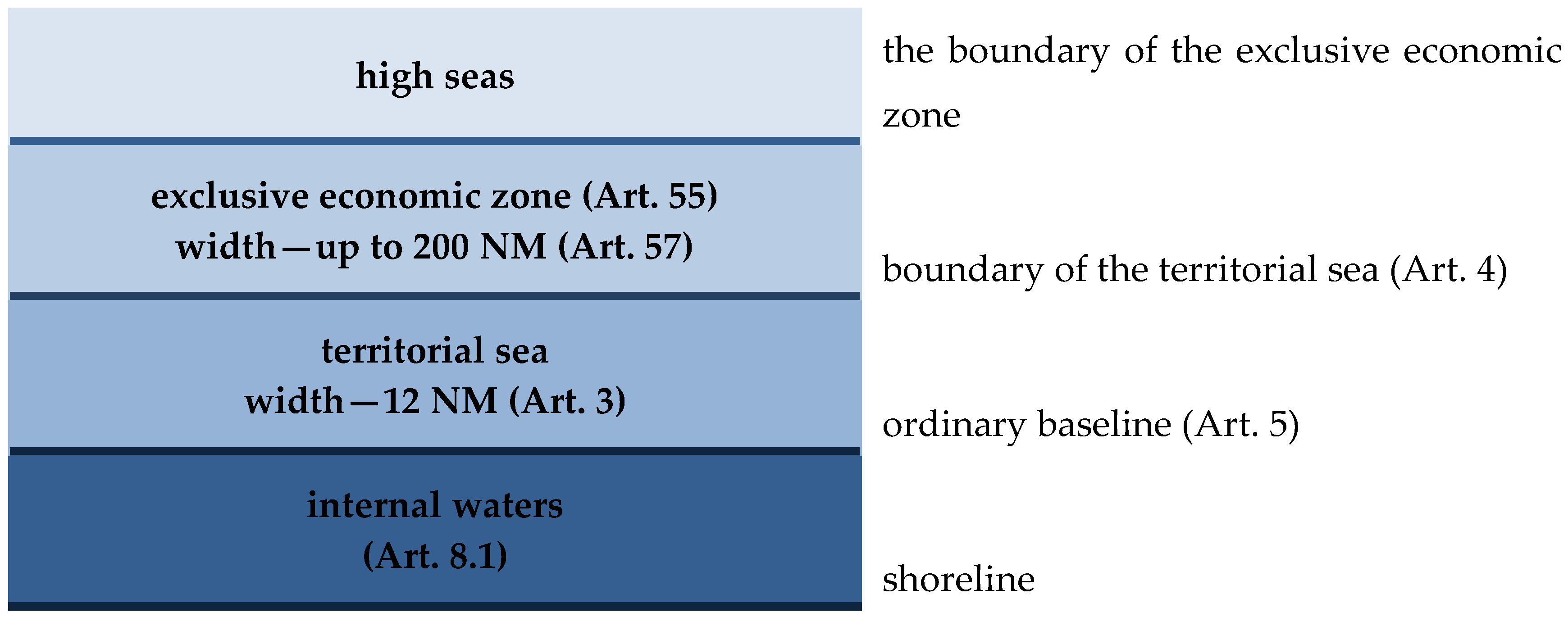

3.1. The Legal Definition of Maritime Areas

A basic document in Maritime Law is the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea [

33]. It was signed by 165 countries, the European Union and Palestine. Also, those countries which have not ratified it (e.g., the United States of America), or even not signed it (e.g., Turkey), recognize it as a codification of customary law of the sea and rely on its provisions [

34]. In accordance with its provisions, the sovereignty of a coastal country extends beyond its land territory and internal waters. Any such country shall have the right to determine the territorial sea of the width not exceeding 12 nautical miles (i.e., 22,224 m). The belt of the territorial sea is measured out from the baselines, i.e., lines corresponding to the lowest water level, run along the coast, officially recognized by the coastal country. The outer boundary of the territorial sea is the line, every point of which is located at a distance equal to the width of the territorial sea to the nearest point of the baseline. The waters situated between the baseline of the territorial sea and the mainland are part of the internal waters of the country.

From the baselines, the boundaries of an exclusive economic zone are also determined, which is an area beyond the territorial sea, which is subject to the specific legal regime. It cannot extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines. The coastal country has the sovereign rights there to explore, exploit, conserve and manage natural resources, marine waters, the seabed and its underground, as well as the jurisdiction with regard to the construction and use of artificial islands, engineering devices and structures, maritime scientific research and protection and conservation of the maritime environment. Beyond the exclusive economic zone, there are only high seas which are open to all countries, both coastal or landlocked. The cited definitions of maritime areas have been illustrated in

Figure 1.

The European Union law defines coastal waters [

35] and marine waters [

36]. They are located within the territorial sea and the exclusive economic zone. Marine waters mean waters, seabed and subsoil located on the seaward side of the baseline, from which the extent of the territorial sea is measured, up to the farthest area of territorial waters, and extending up to the farthest area where a Member State has or exercises jurisdiction rights, in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The coastal waters, on the other hand, are surface waters on the landward side of the line, every point of which is at a distance of one nautical mile on the seaward side from the nearest point of the baseline, which width of territorial waters is measured from, extending where appropriate, up to the outer limit of transitional waters (part of the surface waters in the vicinity of river mouths which are partly saline due to proximity to coastal waters, but which are substantially influenced by freshwater flows).

According to [

37] maritime areas of the Republic of Poland include internal marine waters, territorial sea, the contiguous zone and the exclusive economic zone. The internal marine waters and the territorial sea are part of the Polish territory. The exclusive economic zone is located outside the territorial sea and is contiguous to that sea. Poland’s supervision and jurisdiction over its maritime areas extends over the waters, the airspace above those waters, and the seabed of internal marine waters and territorial sea, as well as over the interior of the earth beneath them.

Between [

33] and [

37] there is a difference in the definition of internal marine waters. Under the Polish law, they are:

part of Nowowarpieńskie Lake and a part of the Szczecin Lagoon, together with the Świna and Dziwna Rivers and Kamieński Lagoon, located east of the international border between the Polish Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany, and the Oder River between the Szczecin Lagoon and the port Szczecin waters,

part of the Gulf of Gdańsk, enclosed with a baseline running from the point 54°37′36″ north latitude, and 18°49′18″ east longitude (on the Hel Peninsula) to the point at 54°22′12″ north latitude and 19°21′00″ east longitude (the Vistula Spit),

part of the Vistula Lagoon, located south-west of the international border between the Republic of Poland and the Russian Federation on this Lagoon,

port waters demarcated from the sea with a line connecting permanent port facilities which are the farthest out to the sea, forming an integral part of the harbor system,

waters situated between the coastline and the baseline of the territorial sea.

Moreover, [

37] introduces the coastal strip, or an area of land contiguous to the sea shore, running along the entire sea coast, which includes coastal technical belt and coastal protective belt.

Technical belt is a zone of mutual direct impact of sea and land, designed to maintain the shore so that it complies with the safety requirements and environmental protection standards. It covers the area from the sea coast line towards the mainland with a width of 10 to 1000 m, depending on the type of a shore, with the exception of land lying within the boundaries of ports and harbors [

38].

The boundaries of the technical belt are determined as the lines connecting boundary points specified and set out in accordance with geodetic and cartographic law [

39], taking into account:

on the dune shores: the beach, the first dune embankment and a strip of land behind this embankment with a width from 20 m to 200 m, counting from the landward foot of the dune embankment,

on the cliff shores: the beach, the base of the cliff, cliff slope and a strip of land with a width of 10 m to 100 m, below the upper edge of the slope,

on the flat shores, without a dune embankment: a strip of land from the sea shore to the waterward foot of levees, or in the absence of levees—a strip of land with a width of 50 m to 1000 m from the sea shore,

on the shores with hydro-technical structures forming the coastline, the area covering these structures together with a strip of land with a total width of 10 m or more, if it results from separate regulations.

Coastal protective belt covers an area in which human activities have a direct impact on the condition of the technical belt. It is contiguous to the landward boundary of the technical belt or sea harbor, of a width of 100 m to 2500 m, and the lake Kopań, Bukowo and Jamno with the strip of land with a width of up to 200 m directly contiguous to them, counting from the boundaries of the record parcels which these lakes are located on, with the exception of the land lying within the boundaries of ports and harbors [

38].

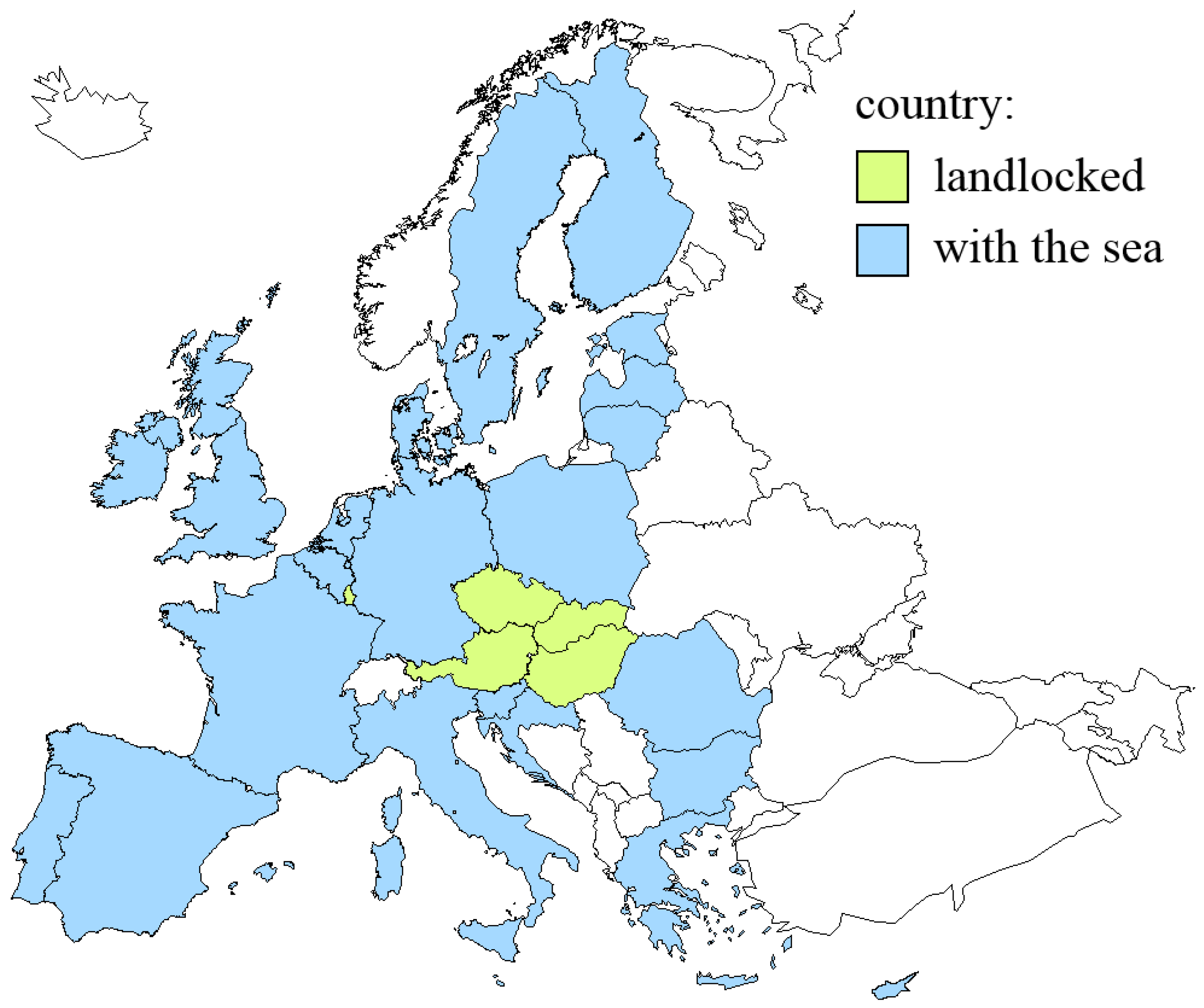

3.2. EU Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning

There are 46 countries on the European continent, 28 of which are already members of the European Union, and a further six enjoy an official EU candidate status. Only five countries of the Community countries have no access to the sea (

Figure 2).

Europe has a highly complex and varied coastline. The islands represent approx. 7.5%, and peninsulas approx. 25% of the continent surface area (own study based on [

40]). It is surrounded by numerous seas and bays, which are parts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Arctic Ocean. Marine waters under the sovereignty and jurisdiction of Member States of the European Union include the following waters [

36]:

the Baltic Sea,

the Black Sea (including the Sea of Azov),

the Mediterranean Sea (including the Adriatic Sea, the Alboran Sea, the Balearic Sea, the Aegean Sea, the Icarian Sea, the Ionian Sea, the Ligurian Sea, the Tyrrhenian Sea),

North-East Atlantic Ocean (i.e., the North Sea, including the Kattegat and the English Channel, the Celtic Sea, the Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Peninsula Coast, waters surrounding the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands, including the waters surrounding the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands).

Waters accessible to individual Member States of the European Union and the length of their coastline have been presented in

Table 1.

The European Union works for the constant development of the European continent, which is based, inter alia, on sustainable economic growth, high level of protection and quality improvement of the natural environment, as well as supporting scientific and technical progress [

41]. Therefore, in order to ensure sustainable growth in the maritime economy, sustainable development of maritime areas and sustainable use of maritime resources, the Directive establishing a framework for Maritime Spatial Planning was adopted in 2014 [

42].

It provides for the integrated maritime policy to enable the implementation of maritime spatial planning for EU maritime areas, taking into account:

interaction between land and sea,

environmental, economic, social and security aspects,

coherence between maritime spatial planning and the resulting land use plan or plans, and other processes, such as Integrated Coastal Zone Management or equivalent formal or informal action,

involvement of the interested parties,

use of best available data,

cross-border cooperation between Member States,

cross-border cooperation with third countries.

As a result of the policy of maritime spatial planning, no later than 31 March 2021, plans should be drawn up for maritime spatial planning, which shall take into account:

areas of aquaculture,

fisheries,

engineering devices and infrastructure for exploration, exploitation and extraction of oil, gas and other energy sources, minerals and aggregate, as well as the production of energy from renewable sources,

sea shipping routes and traffic routes,

military areas,

nature and species conservation areas and protected areas,

areas of raw material extraction,

research studies,

the course of submarine cables and pipelines,

tourism,

underwater cultural heritage.

The Directive applies neither to coastal waters or parts thereof, subjected to spatial planning of urban and rural areas, provided that this will be specified in spatial planning of maritime areas, nor to land covered by the planning.

Maritime spatial planning should have been implemented and established by each Member State until 18 September 2016, but the landlocked countries were not obliged to transpose and apply the Directive.

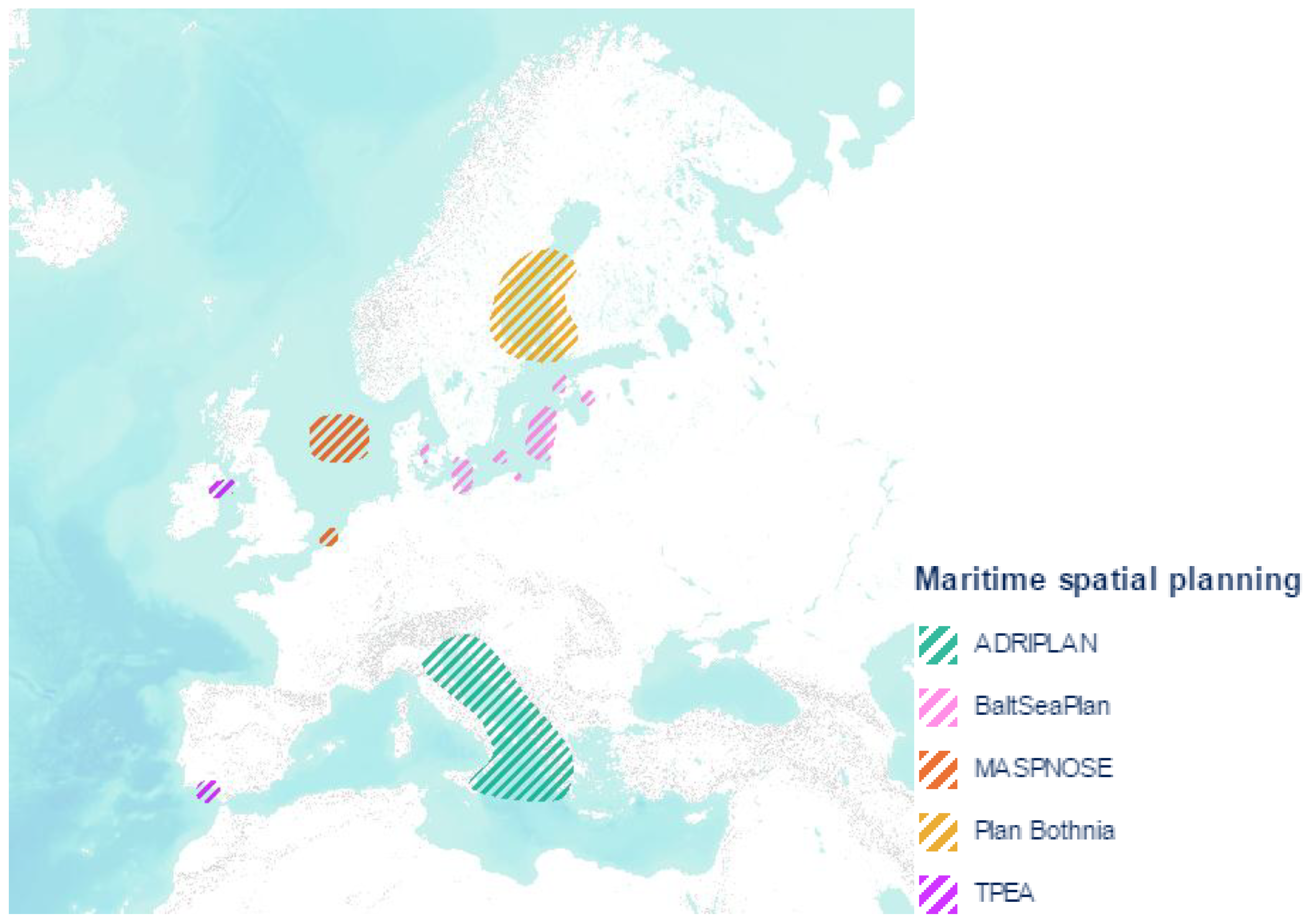

Preparatory activities for maritime spatial planning of the European Union have been performed as part of the projects (

Figure 3):

MASPNOSE, conducted in the North Sea in 2010–2012,

Plan Bothnia, conducted in the Gulf of Bothnia of the Baltic Sea in 2010–2012,

BaltSeaPlan, implemented under the Baltic Sea Region Program “Introducing Maritime Spatial Planning in the Baltic Sea”, in 2009–2012,

TPEA, for cross-border maritime spatial planning in European waters of the Atlantic, including the Celtic Sea and the Bay of Biscay, conducted in 2012–2014,

ADRIPLAN, conducted in the Adriatic Sea and the Ionian Sea in the years 2013–2015.

Prior to that, from April 2006 until April 2008, the planning procedures were checked in the PlanCoast project. Its goal was to develop tools and possibilities to effectively integrate spatial planning in coastal zones and maritime areas of the Baltic Sea, the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea.

3.3. Spatial Planning in the Area of the Polish Part of the Baltic Sea

European Union Member States may include regulations or mechanisms into the spatial plans of maritime areas, or develop these plans based on the existing national strategies. These regulations or mechanisms must meet two conditions:

they have been or will be established prior to their entry into force [

42],

their content is in accordance with the requirements [

42].

As part of BaltSeaPlan, on the Polish coast the following were created: a pilot project of the land use plan for the Polish part of the Central Shoal; a project of assessing the environmental impact of the pilot project of the land use plan for the western part of the Gulf of Gdansk; and a pilot project of the land use plan for the Pomeranian Bay. PlanCoast led to the creation of a pilot project of the land use plan for the western part of the Gulf of Gdańsk.

Over the Polish part of the Baltic Sea, planning works are being carried out all the time, at different levels of detail. Their goal is to create planning studies for land and maritime areas (

Table 2).

Planning documents include development strategies as well as programs and program documents, created as part of the so-called development policy (

Table 3), i.e., a group of interrelated activities, undertaken and implemented in order to ensure sustainable and balanced development of country, socio-economic, regional and spatial coherence, higher competitiveness of the economy and creating new workplaces on a national, regional or local level [

45].

Several international organizations are also involved in the spatial planning in the Baltic Sea region (

Table 4).

Although there is no obligation to take the studies prepared by them into account for maritime spatial planning, a joint Working Group HELCOM (The Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission—the international organization proclaimed by the so-called Helsinki Convention of 1974 as its executive body, whose task is to monitor and protect the natural environment of the Baltic Sea) and VASAB for maritime spatial planning, have proposed to create the so-called Road Map for Maritime Spatial Planning of the Areas of the Baltic Sea 2013–2020. It was adopted by the HELCOM Ministerial Conference in 2013 and received support in the Declaration of VASAB Ministerial Conference in September 2014. From its records it was evident that maritime spatial planning should have been regulated in all Baltic States before 2017. Before the end of 2020, national maritime land use plans are to be drawn up. The plans have to be consistent across borders [

46].

3.4. The Land Use Plan for Maritime Areas

The basic document for spatial planning in Poland, i.e., the Act on Spatial Planning and Land Development of 2003 [

44] says that the intended zoning of land, the location of public investments, the land-use and land development conditions, in relation to maritime areas, are determined by the Maritime Areas Act of the Republic of Poland and Maritime Administration [

37].

The land use plan for marine internal waters, territorial sea and exclusive economic zone, by regulation, may be adopted by a minister responsible for maritime affairs and minister responsible for regional development, in consultation with the ministers responsible for the matters of the environment, water management, culture and national heritage protection, agriculture, fisheries, transport, internal affairs, and with the Minister of National Defence.

The minister decides on [

37,

51]:

intended use of the areas of internal marine waters, territorial sea and exclusive economic zone, in particular for the needs of:

- ○

maritime transport,

- ○

sports, tourism and recreation,

- ○

marine breeding and cultivation,

- ○

fishing,

- ○

construction of artificial islands, structures and engineering devices,

- ○

technical infrastructure,

- ○

ensuring safety and public order,

prohibitions or restrictions on the use of maritime areas, taking into account the requirements of environmental protection, in particular in the fields of scientific research, shipping, fishing, construction and use of artificial islands, structures, engineering devices and technical infrastructure, bathing and motorboat sports,

the location of public investments,

directions of the development of transport and technical infrastructure, also shipping, including boundaries of the zones closed to shipping and fishing, continuously and periodically,

areas and conditions of environmental and cultural heritage protection, including protected waters in spas, permanently and temporarily protected districts regarding fisheries, areas with mineral deposits, documented or confirmed by preliminary studies and information contained in geological maps, and mining areas covered by concessions.

The plan should take into account [

51]:

objectives and directions set out in development strategies and programs created to implement development policy,

objectives and directions of sustainable development of the country, as defined in the concept of spatial development of the country,

objectives, principles and directions of spatial policy of provinces, as defined in spatial planning of provinces,

public purpose investments of national importance, included in the programs of government tasks used to implement public purpose investments of national importance,

settlements of local land use plans of appropriate coastal municipalities,

settlements of studies of conditions and directions of spatial development of appropriate coastal municipalities,

settlements of the plans for the protection of national parks, nature reserves and natural landscape parks, as well as conservation plans for Natura 2000 sites, and other forms of nature protection,

valid permits for the construction and use of artificial islands, structures and engineering devices in Polish maritime areas, and the laying and maintenance of submarine cables and pipelines in the marine internal waters and the territorial sea, issued before the plan entry into force,

concessions issued under [

52], for the exploration or prospecting of mineral deposits, hydrocarbon from deposits, underground carbon dioxide storage, extraction of minerals and hydrocarbons from deposits, underground non-reservoir storage of substances, waste and carbon dioxide, as far as they concern maritime areas covered by the plan.

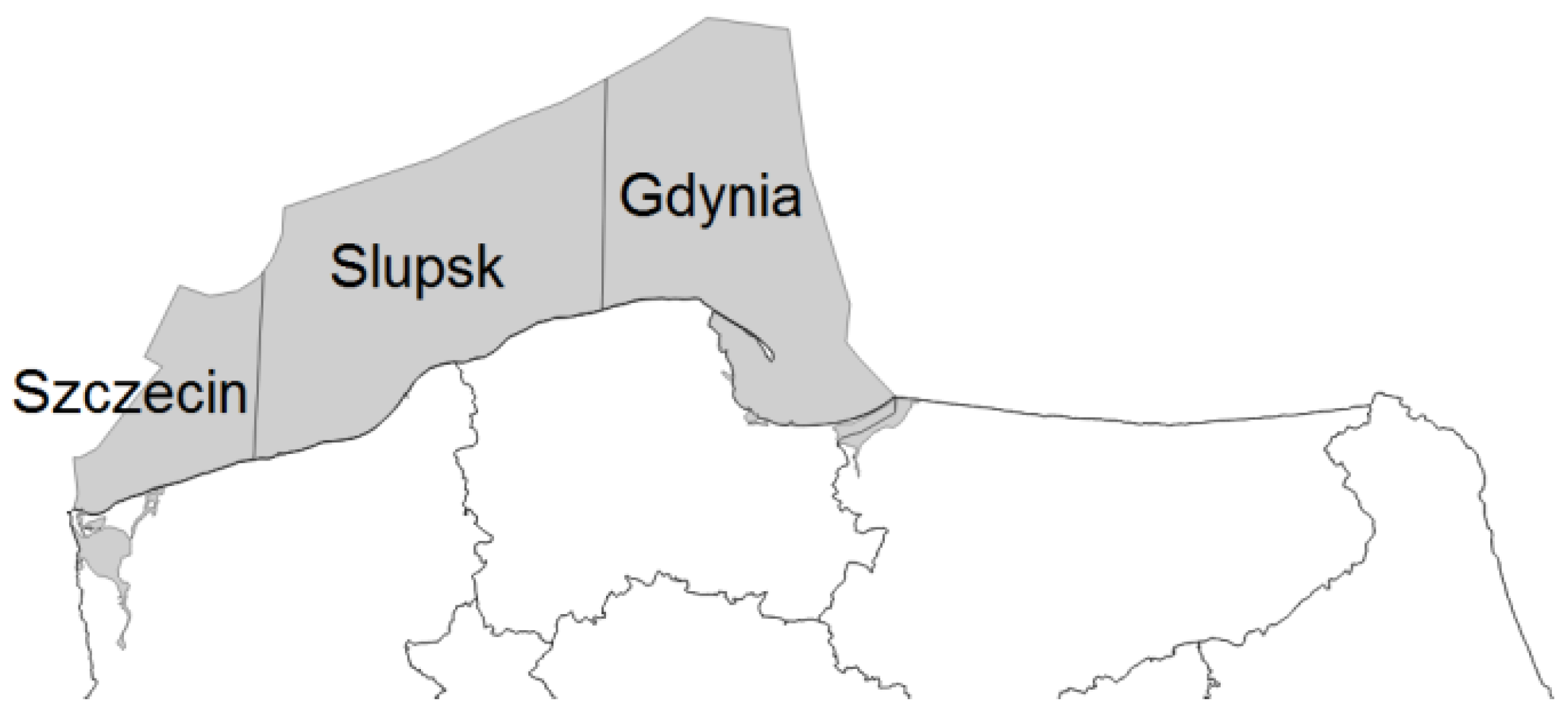

Due to the fact that it is prohibited to erect and use wind power stations in internal marine waters and territorial sea, the plan must take this into account.

The draft plan is drawn up by the managing director of a maritime office, competent for the area covered by the plan. In the territory of the Republic of Poland, there are three maritime offices (

Figure 4): in Gdynia, Słupsk and Szczecin.

The environmental impact assessment including statement of reasons with a description of the existing condition, the characteristics of considerations regarding zoning the area covered by the plan and indicating the grounds for the issuance of a planning decision contained in the plan settlements, are prepared for the draft land use plan.

The draft plan is prepared using current planning materials and source data. The former are understood as documents and studies prepared for the needs of the plan, study, analysis, assessments, adopted studies and decisions issued by the competent authorities for the contiguous area of land. The source data, on the other hand, is information about a specific area, having an impact on its future use, in particular regarding the existing shipping routes, protected nature areas, places of prospecting, exploration, or extraction of mineral deposits, location of technical infrastructure, shipwrecks, storage of excavated material, military areas, areas of cultural heritage, live fish stocks and fishing activity, tourism, existing and planned land use for the land and maritime areas contiguous to this area, ecological risk models, as well as maps, documents and studies referring to the area covered by the plan, drawn up on the basis of separate regulations.

Poland does not have a spatial plan for maritime areas. The works on the plan are conducted in the following stages [

46]:

study of conditions of spatial development,

development of the draft plan,

conducting cross-border consultations.

For this purpose, already in 2013, an agreement was signed between the managing directors of the Maritime Offices in Szczecin, Słupsk and Gdynia, on cooperation in preparing the study for the Polish maritime areas and the spatial development plan for the Polish maritime areas. According to its content, one single coherent draft spatial development plan is prepared for the Polish maritime areas.

After the adoption of the plan, it will be necessary to perform additional studies, resulting from the indications contained in the strategic plan, and to prepare more detailed plans for the areas specified therein, i.e., lagoons, harbor areas and selected water bodies.

The study of conditions of spatial development of the Polish maritime areas, together with the spatial analyses, were completed earlier than expected, i.e., in November 2014. It covers maritime areas, in part referring to the exclusive economic zone and the territorial sea of the Republic of Poland, as well as the belt of marine waters located between the baseline of the territorial sea and the boundaries of the record parcels of the land area, contiguous to the marine waters, including internal marine waters of the Gulf of Gdansk. It consists of two parts: the text and the graphic part, which includes 23 maps. It is an inventory and assessment of the condition of maritime areas, it is of informative nature only. The study was drawn up in order to collect and analyze data for the purpose of preparing the land use plan for the selected part of the Polish maritime areas. It is not binding on local authorities involved in drawing up local plans for land areas.

The information contained herein covers the following issues [

53]:

oceanographic, i.e., physical and chemical parameters, depth, currents, waves, winds, storms intensity, water levels, etc.,

natural, i.e., boundaries of the areas protected by law, occurrence of habitats and rare species of flora and fauna, photic zones, spawning-grounds and feeding sites for industrial fish.

hydromorphological, i.e., dynamics of the shoreline,

geological, including the types of deposits and mineral resources.

The study also presents the analyses of land areas contiguous to the maritime areas contained herein, the existing methods and potential future uses and ways of management of maritime areas, including for the purposes of renewable energy, mining and mariculture.

The works on a draft of the land use plan of Polish maritime areas started back in July 2016. Over the course of the second project stage, comments and conclusions of the draft plan were collected and the planning materials, necessary for developing the preliminary draft plan, were obtained. In 2017, national and international consultative meetings and industry consultations were held. As a result, in June 2018 a draft of land use plan for Polish maritime areas was made publicly available. Nowadays, the next version of the draft plan is underway and it takes into account the opinions and comments submitted up to the date. As per the project plan, in October 2019 a draft plan is to be submitted to the minister of maritime economy for acceptance and adoption of the plan in a way of a regulation.

3.5. National Spatial Development Concept

The effective concept of spatial development of the country is the resolution of the Council of Ministers of 13 December 2011 [

54]. It contains in particular [

44]:

basic elements of the national settlement network,

requirements of environmental protection and monuments, including the protected areas,

distribution of social infrastructure of international and national significance,

distribution of objects of technical infrastructure and transport, strategic water resources and water management facilities of international and national significance,

functional areas of supra-regional significance.

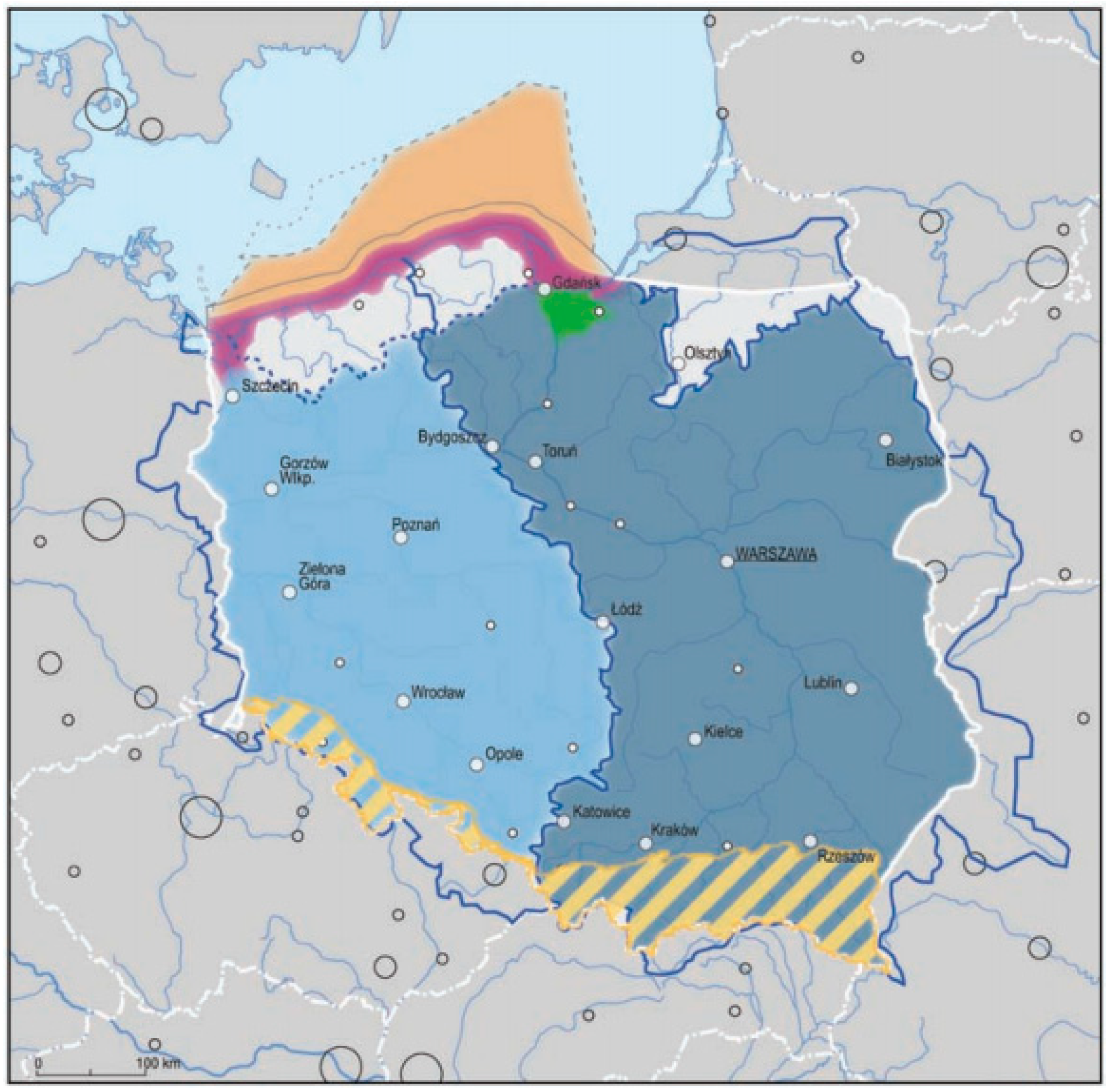

The latter ones were distinguished based on a dominant problem of spatial nature, whose range of influence extends beyond the local, and even regional, sphere. They require a special approach in terms of spatial development policy of the country. The current concept of spatial development of the country identifies (

Figure 5):

the coastal zone,

the Polish exclusive economic zone,

the mountain areas,

Żuławy region,

Soil protection areas for the purposes of agricultural production,

closed areas,

areas at risk of flooding in the river basins.

For maritime spatial planning, the coastal zone (purple) and the Polish exclusive economic zone (orange) are, of course, the most important.

Pursuant to the provisions of the concept, the state administration authorities and local self-government bodies at all levels, are responsible for spatial planning of the coastal areas. To lay the grounds for the spatial integration of the maritime areas and to use it optimally, the following should be developed:

A specially appointed team is to be held responsible for the preparation of the study. The study is to include settlements binding for the maritime administration, provincial governments, and through the spatial development plan of the province, also coastal municipalities while creating their respective strategies, plans and programs.

The plan is to be drawn up with specifying at the same time the procedures guaranteeing the correlation between spatial development plans of the maritime area and of the land part of the coastal zone. Preparation of the development plans for maritime areas and development plans for land areas at the interface with maritime areas, should be subjected to the mutual consultation procedures between the authorities responsible for their preparation. In order to draw up plans for maritime spatial development, it is necessary to define expectations with respect to the coastal zone, resulting from the needs of the land areas.

Distinguishing the Polish exclusive economic zone as an area of supra-regional significance is supported by the fact that this is an area which:

creates a compact spatial arrangement, consisting of functionally related waters, characterized by common considerations as well as predicted, uniform development objectives,

is subjected to customary international law requiring multilateral cooperation,

is not private property, and the right to dispose of the space by proprietors is limited,

is sensitive to imbalance,

has a small group of interested parties,

ceased to be a good which is relatively abundant.

The functional area plan should be part of the land use plan for maritime areas, drawn up for the coordination of the defined investment locations and their protective zones, the zones of occurrence of dangerous objects, protection of cultural heritage, flora and fauna with the use of shipping. It should be correlated with the study of spatial development for coastal areas and include provisions binding for the provincial governments, and through the provincial plan, also selected municipalities connected with the area covered by the plan, mainly regarding technical infrastructure.

3.6. Land-Use Plans at the Provincial and Municipal Levels

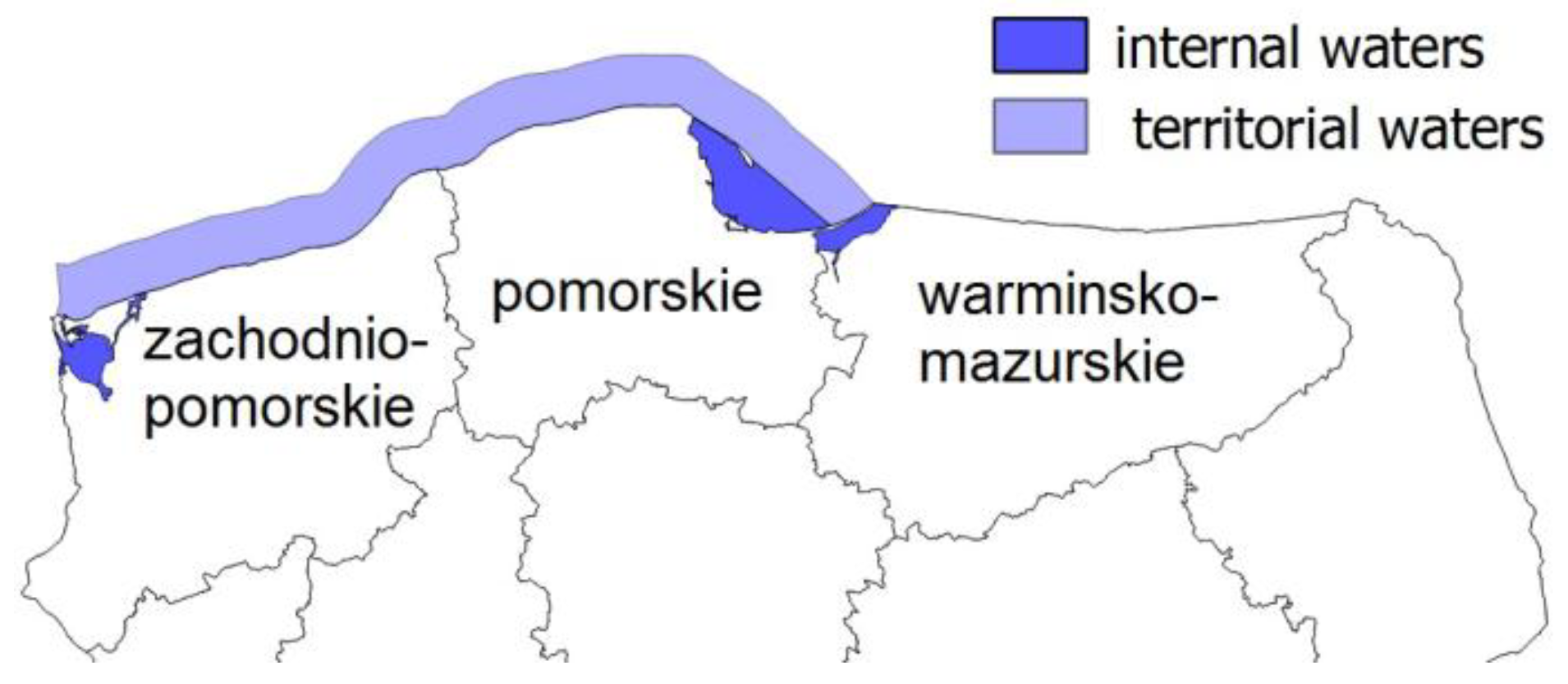

The Polish part of the Baltic Sea includes three provinces (

Figure 6): West Pomerania, Pomerania, as well as Warmia and Mazury. The latter one is bordered only with the internal waters of the Vistula Lagoon.

For each of these provinces there are land use plans drawn up, taking into consideration [

24]:

basic elements of the province settlement network and their communication and infrastructure links, including directions of cross-border connections,

system of protected areas, including areas of environmental protection, protection of nature and cultural landscape, protection of spas and of cultural heritage, monuments and contemporary cultural assets,

location of public purpose investments of supra-local significance,

boundaries and principles of managing functional areas of supra-regional significance and, depending on the needs, boundaries and principles of managing functional areas of regional significance,

special flood hazard areas,

boundaries of closed areas and their buffer zones,

areas with documented mineral deposits and documented complexes of carbon dioxide storage.

At the municipal level, local land use plans are drawn up, i.e., legal provisions adopted by the municipality councils in the form of a plan drawing and a text, which presents the future considerations of the area. They form the grounds for any investment undertakings [

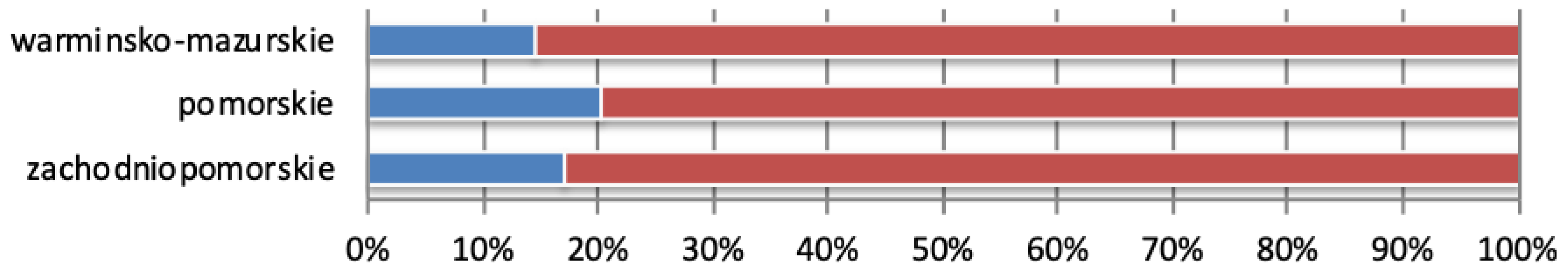

2]. They take into account a variety of issues, and their preparation is preceded by performing of a number of analyses, including a study of conditions and directions of spatial development. Due to the fact that there is no obligation to draw up local plans, only approximately 17% of the area of the three Baltic provinces is covered by them (

Table 5 and

Figure 7). In this case, the majority of investment plans are carried out on the basis of a zoning permit, which does not have to be compatible with any planning document which is higher in the hierarchy.

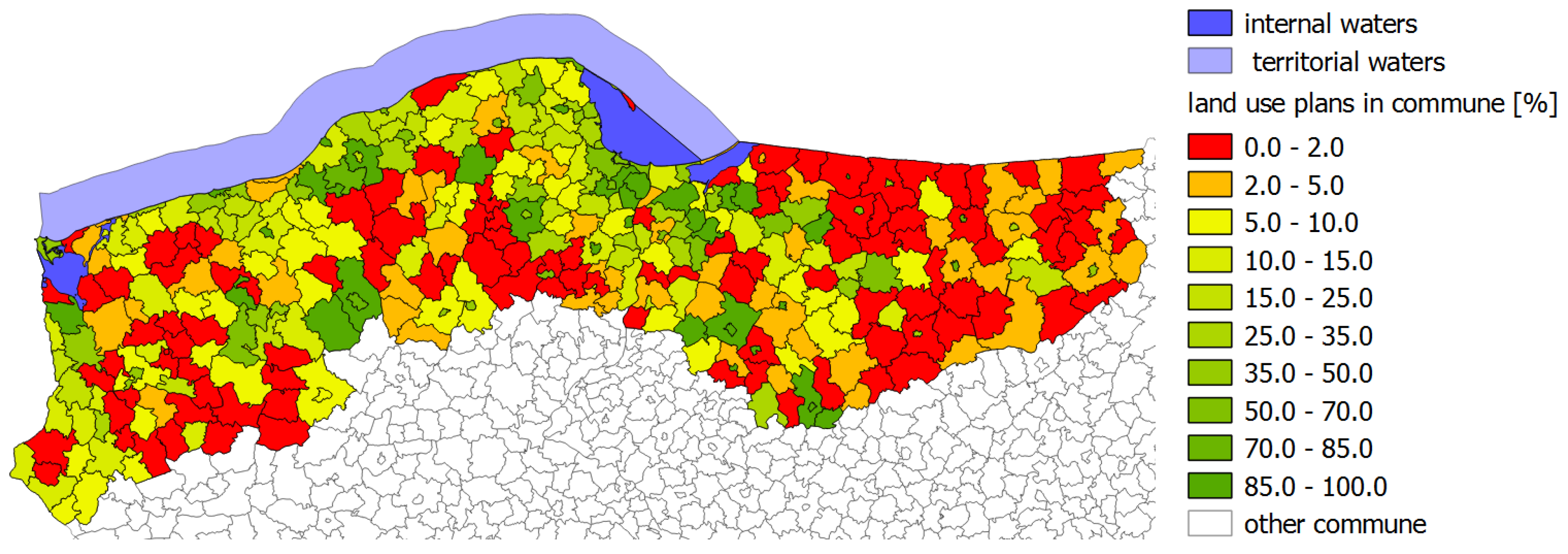

Due to the small coverage of the region with the local plans, it was decided to verify what it looks like in each individual municipality (

Figure 8).

As depicted in

Figure 8, coastal municipalities adopt local land use plans the most frequently, but the area of the municipalities which they cover is not large. The seafront is dominated by the municipalities which have adopted plans for at least over ten per cent of their surface. Larger touristic cities, such as Kołobrzeg or Puck, try to have resolutions adopted for the entire administrative area. Unfortunately, there are those municipalities where there are no plans at all, or which were drawn up for small areas only.

3.7. Adjustment of the Polish Legislation to the EU Legislation

Poland responded quickly to the necessity of transposition of the Directive establishing a framework for Maritime Spatial Planning. The bill, which would adjust the Polish law to the EU law was already created in the first quarter of 2015. The changes were introduced mainly in the act on the maritime areas of the Republic of Poland and Maritime Administration. The EU Directive didn’t require any modifications in the provisions relating to spatial planning on land areas.

The baseline is defined more precisely in the Regulation [

56], to which the delegation is included in the amended Act on maritime areas. This was due to the fact that all the Baltic countries, with the exception of the Republic of Poland, had a clearly defined course of the baseline using geodetic coordinates.

The waters situated between the coastline and the baseline of the territorial sea, unclassified before 2015, are classified to the internal waters. This led to the determination of the coastline in accordance with [

57], as described in [

58,

59]. As the coastline is subjected to erosion and varies with time, it is off the map in many areas. However, since the area contiguous too it was not subjected to the Water Law, the coastline could not be established in accordance with its provisions.

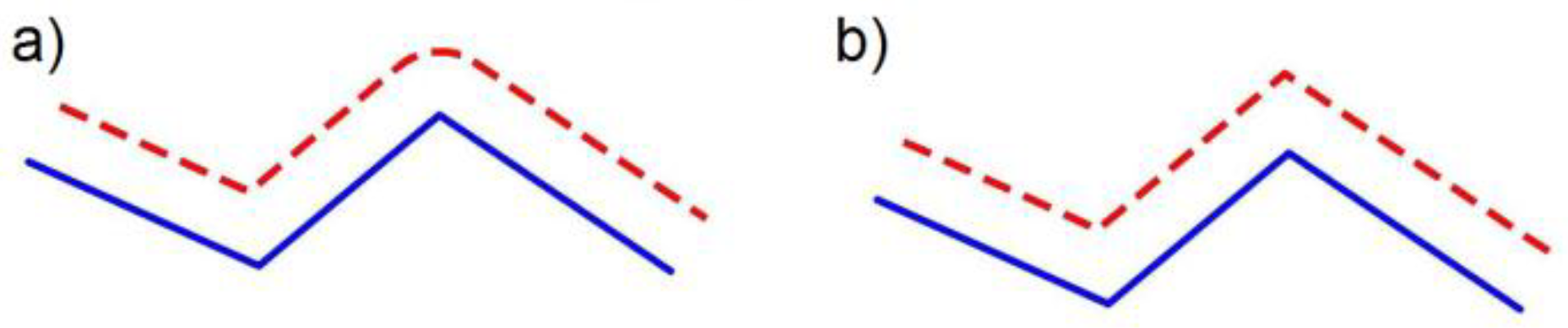

The outer boundary of the territorial sea is a broken line parallel to the baseline, distanced by about 12 nautical miles from the baseline (

Figure 9b), and not, as it was earlier, by 12 nautical miles at every point (

Figure 9a). Its course is also specified in the regulation [

31].

On the maritime areas of the Republic of Poland, a maritime zone it is established, contiguous to the territorial sea. This zone is a belt with a width of 12 nautical miles with the outer boundary as a broken line, specified in the regulation, parallel to the baseline, 24 nautical miles from that line.

The Act on maritime areas clarifies the procedures for the authorization of the location of artificial islands, devices and structures in the Polish maritime areas, permits for the laying and maintenance of submarine cables and pipelines in the Polish maritime areas, and the planning procedure for maritime areas has been improved as well. In the future, several different land use plans for internal waters, territorial sea and exclusive economic zones are to be drawn up. In addition, it contains settlements on the areas and conditions for fishery and aquaculture, as well as for generating renewable energy.

The draft plan is drawn up by appropriate territorial managing director of a maritime office. However, it was compulsory to use an ecosystem approach in the process, and take into account:

economic, social and environmental aspects,

support of sustainable development and growth in the maritime sector,

co-existence of relevant activities and uses of the sea.

From the delegation to the regulation concerning the required scope of the plans, it appears that its graphic part will be implemented in the form of databases.

Maritime administrative authorities are able to conduct analysis and studies, develop concepts and programs in order to draw up a plan, and also cooperate with coastal municipalities to ensure consistency of the plan with land use plans for land areas.

The plan includes provisions binding on provincial governments and municipalities, with internal marine waters, or municipalities neighboring the area of the plan by the shoreline, or by the boundaries of maritime areas equivalent of this line during the preparation of spatial development plans for provinces, studies of conditions and directions of spatial development of municipalities and local spatial development plans and urban planning provisions, respectively, in the following areas:

location of public purpose investments of national significance, contained in the medium-term national development strategy and other development strategies, national spatial development concept and programs of government tasks,

protected areas, including areas of protected space,

manner of use of maritime areas, including the restrictions and approvals.

After the commencement of the work aimed to draw up a plan, the managing director of a maritime office shall make information about the possibility to submit comments and remarks on the plan public (over a period not shorter than 60 days) and shall notify in writing institutions and authorities competent to settle and review the draft plan. The director also addresses the General Director of Environmental Protection and the Chief Sanitary Inspector to agree on the scope and level of detail required for the Environmental Impact Assessment of the draft plan.

The draft plan is drawn up taking into account the above conclusions and settlements, and the alternative arrangement of the selected projects. Then, the environmental impact assessment of the plan is prepared. The draft plan is laid open for public inspection, and submitted for a review by:

the provincial conservator,

the director of the regional water management board,

the minister of health,

the competent mining supervisory authority,

the competent authorities for the strategic environmental impact assessment,

the director of the regional water management board.

It is also agreed with:

commune heads, mayors or presidents of the cities located in the immediate vicinity of the project area,

the regional conservation director,

the Minister of National Defense and the ministers of: economy, fisheries, environment, water management, internal affairs, tourism, communications, transportation, culture and national heritage protection,

the Marshal,

the director of the national park.

These authorities, within its functional and territorial competence, are obliged to cooperate in drawing up the plan by reviewing, submitting proposals and sharing information, no later than 45 days from the date of making the draft plan laid open for public inspection, together with the environmental impact assessment. The managing director of a maritime office may approve the draft plan as agreed if the authorities specified above have not declared any proposals or remarks within the prescribed period of 45 days.

Having considered all remarks, proposals and reviews of the draft plan, modifications are introduced, and the project is once again agreed upon in the necessary extent. The draft plan is presented to the minister of regional development in order to assess its compliance with the objectives and directions set out in the long-term national development strategy, settlements of the medium-term national development strategy, and other development strategies, national spatial development concept and programs of government tasks.

In the case of identifying the possibility of a significant transboundary environmental impact as a result of the implementation of the planned settlements, the managing director of a maritime office informs the General Director of Environmental Protection about such a possibility, and then provides him/her with a draft plan with an environmental impact assessment. After carrying out the proceedings regarding the transboundary environmental impact, the director of a maritime office again applies for the reviews and settlements with reference to the modifications to the draft plan.

A completed draft plan is presented to the minister of maritime economy for its adoption.

If, after the presentation of the draft plan, any modifications are made, the minister, having considered the remarks and proposals, may refer the draft plan to the competent regional director of a maritime office to resume activities necessary to introduce these modifications. The resumed activities include only the part of the draft plan subjected to the modification.

If, as a result of amendments to the specific provisions, a necessity arises to amend the plan, the update procedure should begin no later than six months from entry into force of the amended special provision. In addition, the land use plan for maritime areas will be subject to periodic assessment, at least once every 10 years.

4. Results and Discussion

The factors of the analysis have been selected based on a detailed study of the Polish spatial planning system, of both sea and land areas. The current conditions of the procedure have been considered to be Strengths (S) and Weaknesses (W), and the expected future phenomena that may affect the assessed procedure to be Opportunities (O) and Threats (T).

Table 6 summarizes the resulting internal and external factors that can have a positive or negative impact on the development of maritime areas (

Table 6).

The weights used in the analysis were determined based on a questionnaire survey carried out among five spatial planning experts. The applied expert method can be classified as the Delphi method implemented in one iteration. The decision not to repeat the questionnaire was made due to the fact that the experts agreed in their opinions.

The surveys contained sets of the factors of the analysis prepared by the authors (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats). The respondents’ task was to rank the presented factors from the most important to the least important ones. The respondents assessed the validity of a given factor using the five-point Tilgner scale [

60]: 1 point—no impact of the factor; 2 points—low impact; 3 points—average impact; 4 points—significant impact; and 5 points—maximum impact. They could also add their own suggestions of factors.

The weights (

Wi) have been determined by converting the results from the surveys using Formula (1).

where

pi represents the arithmetic mean of the values assigned by the respondents to the

i-th factor. The values obtained in this way have been rounded up to 5%.

The authors have decided that such a small number of respondents has been sufficient because the Delphi method does not require the expert group to be a representative sample for statistical purposes [

61]. In addition, there is very little empirical evidence about the influence of the number of respondents on the results of the Delphi method. That is why their reliability is assessed based on the characteristics of the experts.

The strengths of maritime spatial planning were identified as follows:

Quick reaction of state administrative bodies to the Directive establishing a framework for Maritime Spatial Planning, which entered into force. Draft amendment to the national regulations relating to the planning of maritime areas in order to transpose EU legislation was created in the first quarter of 2015, which is less than six months after publication of the Directive.

Increasing the attractiveness of investing in Polish maritime areas, which in turn will translate into a more dynamic development of the maritime economy and will intensify employment in the maritime sector.

Ability to use the existing planning documents to develop land use plans for maritime spatial planning based on the implemented Directive establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning.

The hierarchical structure of spatial planning in Poland, the consequence of which is a strong connection between all planning documents created by public administration. As a result, documents created at lower levels than plan for maritime areas may assist in decision-making processes, taking place with its participation.

Identification of the areas intended for selected forms of activity, which will enable carrying out of the process of maritime spatial planning in a sustainable manner, consistent with the long-term, economic and social interests of the state.

Digitization of development plans for maritime areas, which will facilitate their accessibility and their use. It will also accelerate public consultations and opinion-forming process.

Weaknesses include:

Reviewing the draft plan after it has been drawn up, instead of cooperation in its preparation process, on the side of the specialists from various fields. It is much more difficult to produce opinion on the finished material.

Low coverage with the plans in the municipalities contiguous to maritime areas. These municipalities should take an active part in creating a plan for maritime areas, however, it is difficult to expect ant interaction if they do not have their own plans, which the maritime area should be consistent with.

The necessity of geodetic definition of a baseline from which the boundaries of all maritime areas are determined.

No geodetic determination of the location of coastlines, from which the areas that will be incorporated into internal waters are defined. These lines should be determined in accordance with the provisions of the Water Law, in the decisions of the managing directors of maritime offices, after determining them in the field.

Locating investments in maritime areas in other ways than through plans. The use of artificial islands, engineering devices and structures in Polish maritime areas, the laying and maintenance of submarine cables and pipelines in internal waters and territorial sea is carried out under licenses. If they were issued before the entry into force of the development plan for maritime areas, they might not have taken into account global factors taken into consideration in the plan.

Prohibition to erect and use wind power stations in internal marine waters and territorial sea, which significantly reduces the possibility of using a renewable energy source, such as wind, in coastal areas.

The opportunities which are identified by the authors are as follows:

The possibility to attract investors and tourists to the Polish maritime areas if, as a result of proper planning, they will develop and will become more and more attractive.

The possibility of funding spatial planning and different types of investments from the European Union.

International cooperation in the preparation of plans for maritime areas, which will offer the opportunity to use the experience of other countries.

The possibility that international organizations might engage in the planning of maritime areas.

Public consultations, as a result of which the planning of maritime areas can go in directions which were not considered by the entities implementing the draft plan.

Growing importance of Polish maritime areas, as a result of proper spatial planning and appropriate investing.

In contrast, the threats are:

The long duration of the settlements regarding the draft plan and probably long-lasting introduction of the amendments resulting from the reviews, a number of entities that affect the final shape of the development plans for maritime areas.

Current degradation of maritime areas, as a result of improper use of resources before the plans for maritime areas are drawn up.

In accordance with [

51] development plans for maritime areas are prepared based on planning materials and source data, which should be up to date. However, it is a documentation from various sources, which is not always up to date, although it should be. It may also happen that the team preparing a draft plan will get incomplete data which are needed to prepare it. Analysis of the source material that can be used for spatial planning was performed by [

62].

Although development plans for maritime areas should be coordinated with other countries, there is a risk that, for various reasons, they may not be sufficiently involved in the planning process.

Obsolescence of the development plan for maritime areas as a result of natural and anthropogenic factors.

The small scale of the plan, which may result in improper location of the areas for various uses. According to the authors, it might be particularly evident in small basins, such as the Baltic Sea.

The interrelationship between the factors presented above have been illustrated in

Table 7 and

Table 8. If, according to the authors, there is correlation—“1” was marked in the tables. In the absence of the relationship—“0” was marked.

Table 7 summarizes the answers to the following questions:

Does the strength allow to use a given opportunity?

Does the strength allow to eliminate a given threat?

Does the weakness restricts the use of a given opportunity?

Does the weakness intensify the risks specific to a given threat?

Table 8 summarizes the answers to the following questions:

Does the opportunity strengthen a given strength?

Does the opportunity allow to eliminate a given weakness?

Does the threat eliminate a given strength?

Does the threat emphasize a given weakness?

The relations in the SWOT and TOWS analyses can form the basis for a strategic analysis based on the proper adjustment of internal resources to external possibilities. The values of interaction between the factors of the analysis allow to point out to one of the four strategies for the development of the maritime spatial planning system. With the assumed configuration of internal and external factors as well as with the determined values of the weights, there are the following policy options:

- -

the aggressive one, when strengths dominate among the internal factors, in connection with opportunities among the external factors,

- -

the competitive one, when weaknesses dominate among the internal factors, in connection with opportunities among the external factors,

- -

the conservative one, when strengths dominate among the internal factors, in connection with threats among the external factors,

- -

the defensive one, when weaknesses dominate among the internal factors, in connection with threats among the external factors.

Table 9 presents a summary of the SWOT/TOWS analysis, and results of the strategic analysis as well as the selection of the strategy itself, have been depicted in

Table 10.

An overall study of the interactions between the factors of the analysis has demonstrated that both in the case of SWOT as well as TOWS relationships, the greatest number of correlations occur between the positive internal factors and the positive external factors. Such dependencies result from the identification of the internal and external factors presented in this article. The current conditions of maritime spatial planning procedures have been identified as internal factors, while the indications of the external factors have been dictated by future phenomena associated with the implemented procedure of creating plans of maritime areas. For the distinguished configuration of factors, it can be stated that the strength of the spatial planning procedure in the form of increased attractiveness of investments in Polish maritime areas strongly corresponds with all the positive future effects of the implementation of the planning development procedure. On the other hand, the least interaction for both SWOT and TOWS relationships occurs for the configuration of the negative internal factors in connection with the positive external factors.

Similar conclusions can be drawn from the strategic analysis of the connections between the individual factors. Both the number of interactions as well as the weighted number of interactions reveal the dominance of positive internal factors in connection with positive external factors. These dependencies prove that maritime spatial planning should be conducted using the strengths of the procedure and the external opportunities. The opportunities of the dynamic development of maritime areas are perceived mainly in the EU subsidies for various types of investments and in the possibilities of attracting investors and tourists to Polish maritime areas. The strengths of the maritime spatial planning procedure result, inter alia, from the awareness that spatial development plans organize human activities in these areas to meet ecological, economic and social objectives. Thus, the European Union law was quickly transposed into national solutions, and the development of spatial plans for Polish maritime areas has begun. Strengths also include the national experience gained in the preparation of land use plans, which translates into maritime spatial planning in aspects such as the hierarchical planning structure, digitization of plans, or the use of the existing planning documents.