1. Introduction

First, it is important to mention that the concept of sanitation here is focused to the collection and treatment of wastewater. In the period of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG’s) 2000–2015 the global use of sanitation facilities rose from 54 to 68%. This falls below the 77% target, leaving 2.4 billion people without access to improved sanitation facilities; therefore, the challenge is huge due to the disparities between countries (

Table 1) [

1]. For this reason, The United Nations has defined a new initiative “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, defines the succession goals and targets of the MDG’s, now called Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s). In this initiative, 2030 has been defined as the deadline to achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene services for all and to end the open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women, girls, and people in situations of vulnerability [

2]. Human development and well-being are defined among other factors by adequate nutrition, gender equality, education, and eradication of poverty; to achieve them, water and sanitation are fundamental [

1].

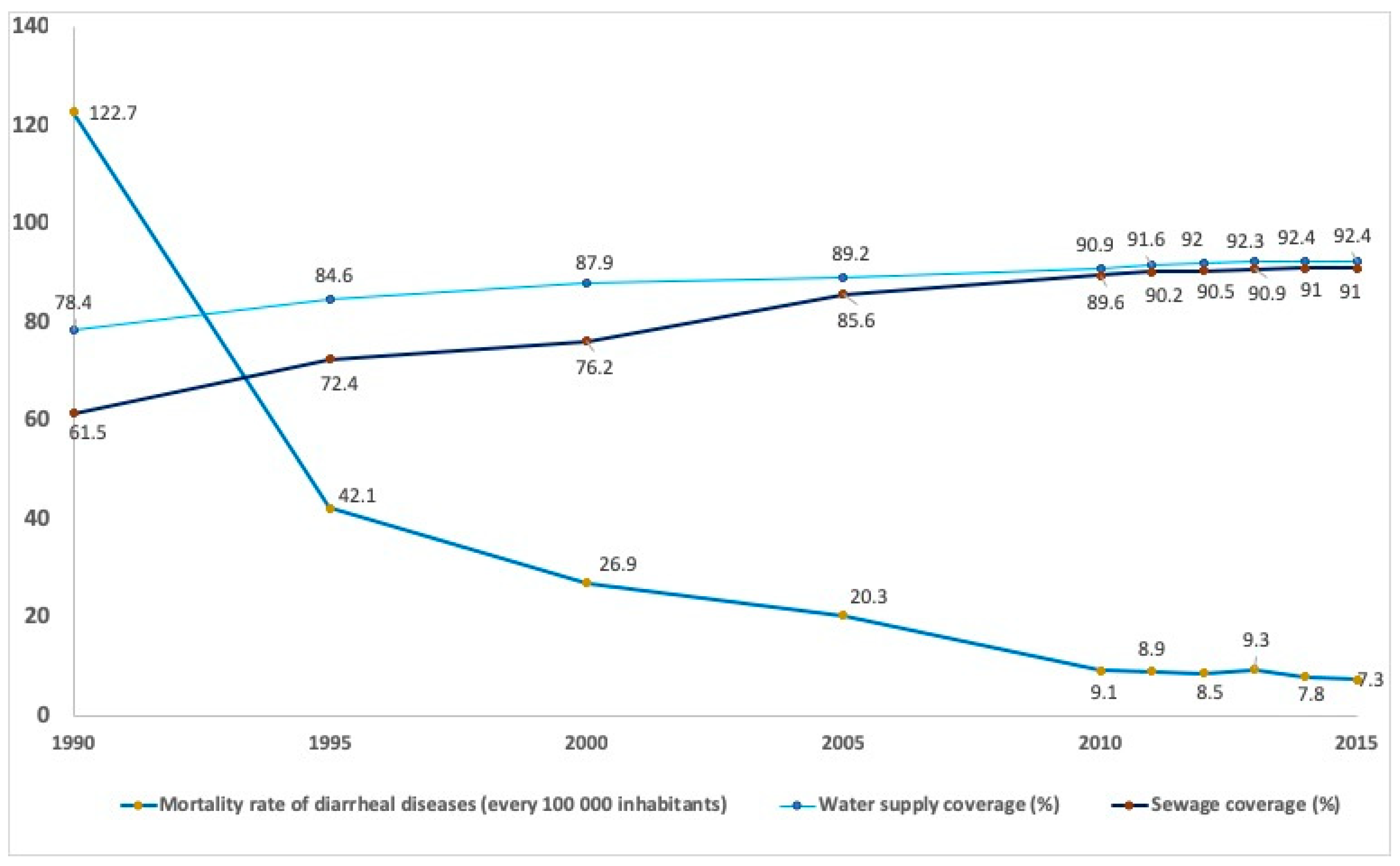

According to the National Water Commission of Mexico (CONAGUA), at the end of 2015 Mexico met the “sanitation” goal with 85% of its population covered with access to improved sanitation services; the national coverage of sewerage was 92.8% (97.4% urban, 77.5% rural); furthermore, 2447 wastewater treatment plants were in operation, treating 120.9 m

3/s of the 212 m

3/s collected [

2]. This achievement has been a tremendous challenge because of the non-uniform distribution of water resources, central and northern parts of Mexico lacks of water availability (Tlaxcala, Aguascalientes, and Mexico City), while southeast has a water resource surplus (Chiapas, Veracruz, and Oaxaca) (

Figure 1). It is important to underline that sanitation coverage reported by CONAGUA is referred to sewerage coverage and not exactly to sanitation (sewerage and treatment); therefore, if treatment coverage is considered, then the level of MDG’s compliance will surely be significantly different. Though numbers about sanitation coverage are useful, there are still weaknesses such as poor quality service, bad operation and low collection efficiency, caused by politicization of services, lack of municipal autonomy, absence of coherent autonomy, and sector fragmentation, among others [

4,

5]. In order to improve sanitation, the construction of wastewater treatment plants in different parts of the country has been prioritized; which implies millions of dollars invested. These stunning engineering projects seem to be the solution, but, without taking into account traditional technologies and communities’ point of view, it results in triggering social conflicts [

6,

7,

8]. Accordingly, one of the great challenges in Mexico is to treat all of the wastewater generated. Despite tremendous efforts and achievements, several projects have not been successful due to the idiosyncrasy of local people and the mismatch between the value provided by the sanitation system and the values of people and/or communities; especially, of people in rural communities [

9].

Consequently, in order to design, choose, and evaluate sanitation systems, sustainable criteria have been reported in the literature [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. They divide the analysis into categories, such as environment, economy, technical function, socio-culture, and human, with a high emphasis on technical part. However, with the aim of having a complete and holistic comprehension of sanitation and all what it implies, the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) that was proposed by Flora et al. [

16] is here used. CCF divides the analysis onto seven categories (capitals): Social, human, political, financial, built (from now on infrastructural) cultural, and natural. These capitals are defined as follows: Social capital involves mutual trust, reciprocity, collective identity, work together, and a sense of a shared future; it is interactive and an attribute of communities, not individuals. Human capital is referred to as the capabilities and potential of individuals, as determined by the intersection of genetics, social interactions, and the environment. It consists of the assets each person possesses: health, formal education, skills, knowledge, leadership, and potential. Political capital consists of organization, connections, voice, and power as citizens turn shared norms and values into standards that are codified into rules, regulations, and resource distributions that are enforced. Financial capital includes savings, income generation, fees, loans and credit, gifts and philanthropy, taxes, and tax exemptions. It is much more mobile than the other capitals and tends to be privileged because it is easy to measure. Infrastructural capital is human-constructed infrastructure. Although new infrastructural capital is often equated with community development, it is effective only when it contributes to other community capitals. Cultural capital determines a group’s worldview, how it sees the world, how the seen is connected to the unseen, what is taken for granted, what is valued, and the potential possibilities for change. It includes the values and symbols reflected in clothing, music, machines, art, language, and ways of knowing and behaving. Natural capital includes the air, water, soil, wildlife, vegetation, landscape, and weather that surround us and provide both possibilities for and limits to community sustainability. It influences and is influenced by human activities. It forms the basis of all other capitals. Capitals can contribute to or detract from communities from being sustainable, when a capital is highlighted over the others, resources are decapitalized, and the economy, environment, or social equity is compromised. CCF has been used in studies of various disciplines [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], giving the opportunity to comprehend how different areas and issues of interest are intimately related.

Here, CCF allows analyzing in the literature what has been and what is being done, focusing on human factors in order to identify whether people’s needs are being considered to guarantee the success of the technologies and resources implemented on sanitation.

2. Materials and Methods

Recently, there have been numerous efforts on research about sanitation [

11,

13,

14,

15], but not much of them directly address the human side of sanitation in political, economic, environmental, cultural, infrastructural and social aspects.

A literature review was carried out following basically two steps. First, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were stablished to select the data to be reviewed. Second, the information obtained from literature was classified and analyzed according to CCF’s concepts [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The Community Capitals Framework was revised and analyzed in order to understand the information to be collected. Then, search of secondary data sources, such as official government information, newspapers publications, and expert’s opinions on sanitation was conducted. It was imperative to have several information sources, such as scientific and technical reports, and project’s results. The search was conducted by accessing to different scientific websites, such as Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Research Gate, SciELO, Readlyc, and official governmental sites. In addition, references of selected data were explored to identify further relevant information. For the analysis, 89 documents were reviewed to identify and discuss the most important aspects of each capital’s condition and their relations. Additionally, a synthesis with the most relevant descriptors was carried out.

4. Discussion

It is important to highlight the lack of information about sanitation in Mexico. Official reports from different governmental programs (PROSSAPYS, APAZU, etc.) are focused on drinking water and sewage, with sanitation being merely mentioned rather than prioritized. On the other hand, most scientific information is focused on the same way [

23,

79,

80], but partially analyzing self-management activities, social perception, and willingness to pay services, mostly in urban areas. There are some exceptions, like [

52], comparing water treatment in both rural and urban areas; and [

58], with the analysis to access to drinking water and sanitation.

It is also important to mention that sanitation problems are not exclusive of Mexico. In Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Europe experience, limited access to drinking water and sanitation increases the incidence of gastrointestinal diseases of infectious origin, which in marginal and indigenous localities can lead to death [

22,

30,

58,

81,

82,

83,

84]. In the case of Colombia, the government has invested 1100 US million dollars in the start-up of wastewater treatment systems from 2011 to the first half of 2013, however, incidences of water-borne diseases, such as acute diarrheal, food-borne diseases, and fever typhoid and paratyphoid, have not decreased in the period 2008 to 2014. Only hepatitis A has decreased [

82]. In Luxemburg, sanitation issues are faced with common solutions, such as building large sewer systems and new centralized treatment plants and continually upgrading and expanding existing infrastructure [

83]. These methods not only imply important costs and investments, but also have significant environmental impacts, as the small receiving water bodies are vulnerable to discharges from wastewater treatment facilities.

As an alternative to conventional systems, ecological sanitation (Ecosan) has been introduced in China, Uganda, and Mozambique; urine diverting toilets in India and Sri Lanka; dry toilets in Japan and dry composting toilets in hot arid climates, just to mention a few. Most of them have been successful with comprehensive and holistic approaches cooperating with different areas interested on diverse issues [

84]. According to Benetto et al. [

83], Ecosan seems to have significant advantage as compared to conventional wastewater treatment systems regarding the reduced contribution to ecosystem quality damage. However, it seems to generate higher impact on climate change and human health than conventional treatment systems due to the emission of some gases during the transport and process of urine and compost (ammonia and nitrogen) that contribute to acidification and global warming; and, the production and end life management of some devices (bio-filter, separation toilets); all of them must be improved to decrease any negative impact.

Meanwhile, ecological sanitation is a promising alternative to small-scale wastewater treatment. At this scale, nutrients flow and losses can be better managed, secondary fertilizer can be easily used by interested farmers and have potential economic value, with related advantages on the environment [

83]. There are many other options, such as anaerobic co-digestion of excreta and organic solid waste that may be feasible to produce biogas or grey water management in urban slums [

55]. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that all sanitation technologies must be tested at the pilot scale to evaluate their performance prior to scaling up for wide application. Equally important, the acceptability by the users and existence of an enabling institutional framework improve chances of technology success, since sustainability requires that institutional arrangements and collection of the waste, treatment, reuse, and safe disposal complement each other [

55].

Following the line where acceptability turns into an important factor of success becomes important to mention the case of some implemented projects. For example, Sinha et al. [

30] assessed the patterns and determinants of latrine use in India, where a governmental program was executed to accelerate sanitation coverage in rural areas and end open defecation. In the period from 1999 to 2010, 64.3 million latrines were constructed. They found that not all individuals living in households with access to latrines use the system, which suggests that the coverage does not necessarily translate into use. This implies that focus should also be placed on the use of the technology rather than only on access and coverage. This confirms Wicken’s analysis [

85], which says that the access to improved sanitation infrastructure is being used merely as an indicator, resulting in the construction of millions of latrines that may or may not lead to improved sanitary outcomes and health benefits, since the use of them is not being assured. Thus, sanitation means more than having access to a latrine; it includes excreta disposal, solid waste, and wastewater management and hygienic practices. Millions of latrines are being constructed each year and yet the frequency of their usage is unknown. Infrastructure is being implemented without sustainable behavior change. This exhaustive work in increase sanitation coverage is additionally related to the change of MDGs to SDGs, where there are 17 new targets to achieve. Focusing on target six: “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” through access to safe and affordable drinking water, adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater, among others [

86]. However, if we evaluate how target six is related to other targets, it can be seen it is directly associated to goals one, three, and eleven, their relation could hinder the achievement not of a single goal, but all of them. The goals are focused on ending poverty in all its forms by ensuring equal access to basic services, reducing the number of deaths and illnesses from air, water, and soil pollution and making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. This interrelation between SDGs also helps to understand the interrelation between the capitals in the CCF and how a weak capital in a community affects all of its capitals, ultimately avoiding them for reaching sustainable development.

According to [

2,

22], communities are poor when the stocks of various capitals are low. Moreover, to face poverty, the investment on natural, cultural, and human capitals must lead the formation of social, political, financial, and infrastructure capital. With the analysis that was conducted in this paper, capitals such as the financial, political, and infrastructure are being prioritized over the natural, human, social, and cultural. This compromises the availability of resources and a quality of life, leading communities to poverty. To reduce the communities’ poverty, it is necessary to identify and transform the community’s capitals for sustainable development; at the same time, it is also necessary to address poverty as a community issue, and to seek place-based, rather than individual solutions, with the intention to understand and engage all of the capitals to set the basis of poverty reduction [

22]. Based on the above, social participation at local levels can help communities to comprehend and value their participation on solving their problems, using tools such as focus groups, workshops, ethnographic studies, and surveys, among others; with local people and stakeholders to make them aware about their responsibility and participation in the design of solutions [

17,

87,

88,

89], as a form of empowerment and involvement in improving their quality of life. In addition, human behavior, adaptation, customs, habits, and livelihoods of communities must be added and emphasized to the design and implementation of sanitation systems to ensure that they are going to be holistic, sustainable, and successful.

Finally,

Figure 3 shows the current pyramidal structure of how sanitation works in Mexico. To achieve a holistic structural change, it must tear apart the current structure and focus on creating balance in all capitals.

5. Conclusions

Evaluating sanitation through CCF allows for identifying the disparities between capitals, there is no social cohesion, government policies, and strategies are not reliable. Health is being affected and weakening human capital, corruption, and all its forms are deeply rooted in political capital. There is no appropriation of the strategies implemented causing wasted economic resources and the pollution of the environment. Financial, political, and infrastructure capitals are being prioritized over the natural, human, social, and cultural, which are compromising the availability of resources and a good quality of live. Drivers that are related to the lack of improved sanitation services in Mexico are population growth, drinking water supply as a top priority, political factors, poor planning, and poor financial resources’ administration.

These findings indicate a direct and complex relationship between the capitals and the provision of basic sanitation services along the country, associated to the inequitable distribution and availability of several resources, mainly in states where the conditions of poverty have been maintained for a long time in the absence of an adequate political framework, the misuse of their resources, among other things, which have caused the slow human, social, and economic development. This in contrast to states with better development conditions but scarce resources availability.

The design and application of holistic studies and frameworks is imperative to estimate the real situation about sanitation in Mexico and potentially worldwide. It is urgent to change the actual way to solve problems, analyzing them as a whole to solve them in a holistic way.