Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- A clear legal mandate and scope for service provision;

- Financial capacity—a solid financial track record with a positive net cash flow over several years;

- Strong management—including business-minded leadership, operational efficiency and strong performance; financial capacity (i.e., strong revenues to cover costs of operations and debt services); and good asset management and business planning;

- Track record of borrowing and repaying debts;

- An asset base against which collateral can be taken.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

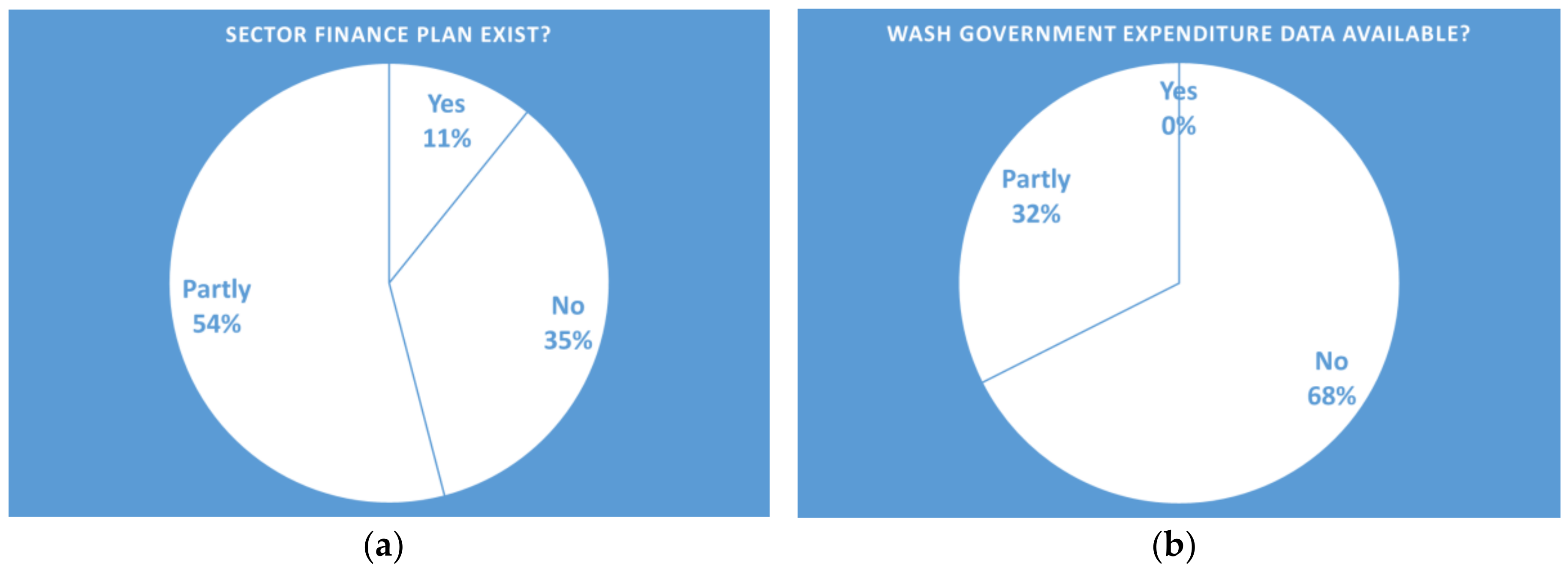

3.1. Governance at the Sectoral Level

3.1.1. Planning and Financing Strategies for Maximising Public and Commercial Funds to Achieve Social Objectives

3.1.2. Effective Tariff-Setting Practices and Economic Regulation

3.1.3. Adequate Performance Regulation and Transparent Accountability Mechanisms

3.1.4. Clarity of Mandate and Performance Obligations of Service Providers

3.2. Service Provider Level

3.2.1. Improved Financial and Operational Management and Efficiency

3.2.2. Capacity Strengthening for Business Planning

3.2.3. Enhanced Autonomy and Legal Framework

3.3. Supply of Finance

- Market finance is abundant and available—provided its risk-versus-reward terms are met—and is needed to close the infrastructure financing gap for services.

- There is no shortage of finance globally; there are excess funds available for investment through both simple and sophisticated private financial systems and instruments.

3.3.1. Rectifying the Mismatch between Commercial Bank Risk Profiles and WASH Sector Realities

3.3.2. Avoiding Mechanisms That Can Result in Market Distortions

3.3.3. Targeting Development Finance for Maximum Impact

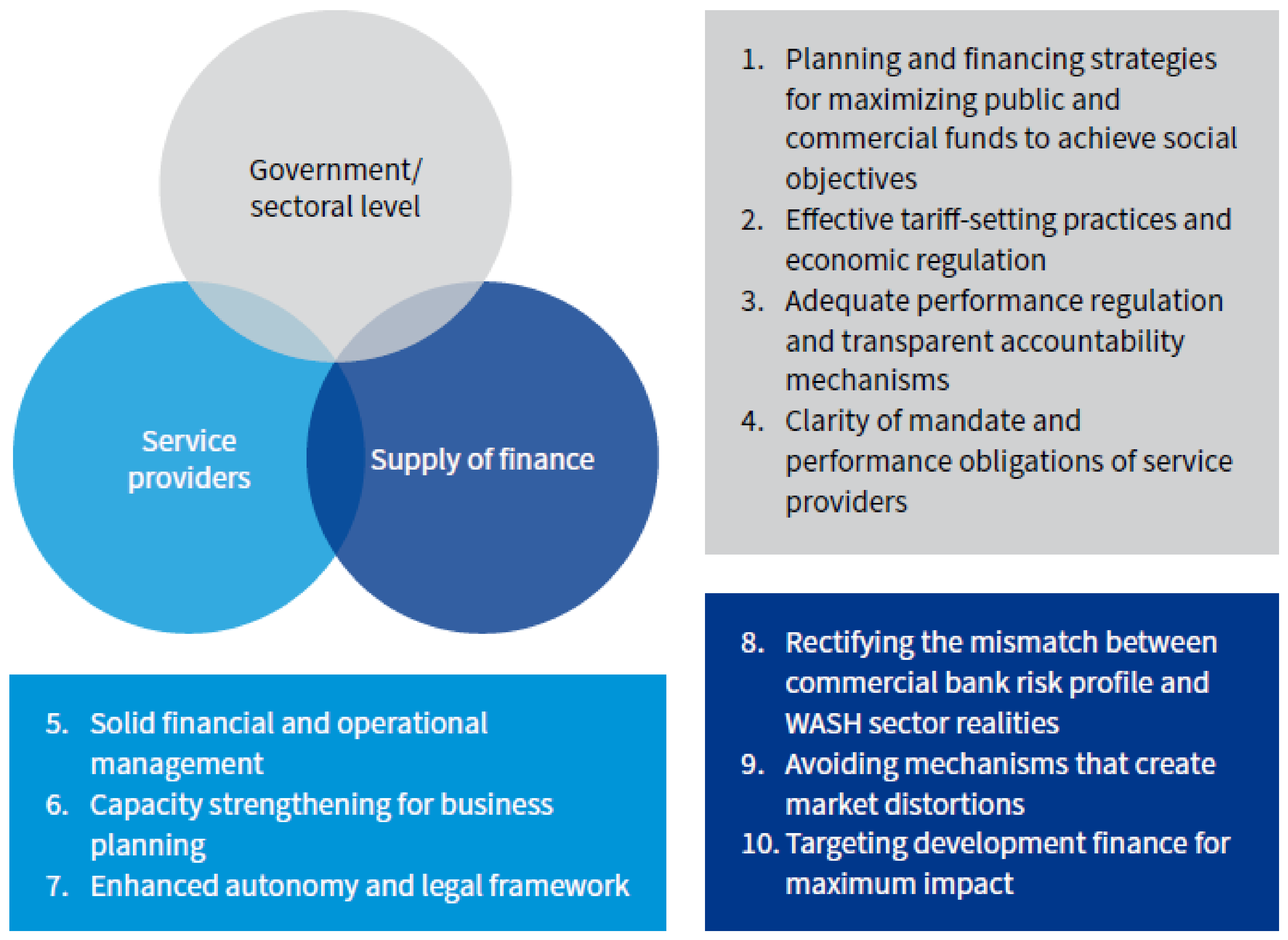

4. Discussion

- -

- The governance, institutional, policy, tariff and regulatory arrangements to ensure transparency, consistency and sustainability (grey box with foundational issues 1 to 4);

- -

- The technical and financial efficiency of service providers to sustain creditworthiness (light blue box with issues 5 to 7);

- -

- Issues related to the supply and suppliers of finance (dark blue box with issues 8 to 10).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hutton, G.; Varughese, M. The Costs of Meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal Targets on Drinking Water Sanitation and Hygiene; Water and Sanitation Program Technical Paper; WSP/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23681/K8632.pdf?sequence=4 (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- World Health Organisation. National Systems to Support Drinking-Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Global Status Report 2019; UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS) 2019 Report; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.; Pories, L. Financing WASH: How to Increase Funds for the Sector While Reducing Inequities: Position Paper for the Sanitation and Water for All Finance Ministers Meeting; IRC Briefing Paper; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://www.ircwash.org/resources/financing-wash-how-increase-funds-sector-while-reducing-inequalities-position-paper (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Amanda, G.; Alex, B.; Bill, K.; Gustavo, S.; Yogita, M.; Gerard, S.; Joel, K.; Vicky, K. Reform and Finance for the Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Sector; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, V. Back to Basics: Sound Utility Business Plans as a First Step in the Sustainability Ladder. 2019. Available online: http://blogs.worldbank.org/water/back-basics-sound-utility-business-plans-first-step-sustainability-ladder (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Bender, K. Introducing Commercial Finance into the Water Sector in Developing Countries; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/423121488451451957/Introducing-commercial-finance-into-the-water-sector-in-developing-countries (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Eberhard, R. Improving Access to Urban Water Sustainably in Sub-Saharan Africa and Beyond: A Way Forward for German Development Cooperation and its Partners Based on a Review of Two Decades of Involvement in Urban Water Sector Reforms in Africa. 2018. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/water/GIZ-Access-Study-Part-II%E2%80%93Narrative-Report-A-way-forward-for-German-Development-Cooperation-and-its-Partners.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Goksu, A.; Trémolet, S.; Kolker, J.; Kingdom, B. Easing the Transition to Commercial Finance for Sustainable Water and Sanitation; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Session%204%20Easing%20the%20transition%20to%20commercial%20finance%20for%20WSS.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- OECD. Making Blended Finance Work for Water and Sanitation: Unlocking Commercial Finance for SDG 6, OECD Studies on Water; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, P. Blended Finance for Water Investments; presentation at 2018 Stockholm World Water Week; OECD: Paris, France, 27 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leigland, J.; Trémolet, S.; Ikeda, J. Achieving Universal Access to Water and Sanitation by 2030: The Role of Blended Finance; WB Working Paper; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/978521472029369304/Achieving-universal-access-to-water-and-sanitation-by-2030-the-role-of-blended-finance (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Van de Lande, L.; Fonseca, C. Global Review of National Accountability Mechanisms for SDG6; End Water Poverty: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frade, J.; Stockholm, Sweden. private conversation, 28 August 2018.

- Mumssen, Y.; Saltiel, G.; Kingdom, B. Aligning Institutions and Incentives for Sustainable Water Supply and Sanitation Services; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29795/126016-WP-P159124-PUBLIC-7-5-2018-12-14-46-W.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Swachh Bharat Progress Key to UN Sustainable Development Goal on Open Defecation. The Hindu, New Delhi. 27 September 2018. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/swachh-bharat-progress-key-to-un-sdg-on-open-defecation/article24886738.ece (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Cummings, C.; Langdown, I.; Hart, T. What Drives Reform? Making Sanitation a Political Priority in Secondary Cities; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, December 2016; Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11262.pdf (accessed on 11 Novemeber 2019).

- United Nations (UN). Financing for Development: Progress and Prospects. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/financing-for-development-progress-and-prospects-2018.html (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Winpenny, J.; Camdessus, M. Financing Water for All: Report of the World Panel on Financing Water Infrastructure; aka Camdessus Report; World Water Council: Marseille, France, 2003; Available online: http://www.worldwatercouncil.org/fileadmin/world_water_council/documents_old/Library/Publications_and_reports/CamdessusReport.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- World Water Council (WWC). Increasing Financial Flows for Urban Sanitation; World Water Council: Marseilles, France, 2018; Available online: http://www.worldwatercouncil.org/en/publications/increasing-financial-flows-urban-sanitation (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Mumssen, Y.; Saltiel, G.; Kingdom, B.; Sadik, N.; Marques, R. Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries: A Fresh Look; Water global practice discussion paper; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/252501542747068978/Regulation-of-Water-Supply-and-Sanitation-in-Bank-Client-Countries-A-Fresh-Look (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Andres, L.A.; Michael, T.; Camilo, L.C.; Alexander, V.D.; George, J.; Christian, B.-V. Doing More with Less: Smarter Subsidies for Water Supply and Sanitation; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IBNET. The International Benchmarking Network. Available online: https://www.ib-net.org/toolkit/ibnet-tools/about-benchmarking/ (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- IBNET Tariffs Dashboard. 2019. Available online: https://tariffs.ib-net.org/ (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- AquaRating. A Rating System for Water and Sanitation Utilities. Available online: http://www.aquarating.org/ (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Inter-American Development Bank. Personal communication, 26 February 2019.

- International Water Association (IWA). IWA and IDB Launch the Digital Platform ‘AquaRating Community of Practice’. 2019. Available online: http://www.iwa-network.org/press/iwa-and-idb-launch-the-aquarating-community-of-practice-that-connects-professionals-around-the-world-to-improve-the-management-of-water-and-sanitation-services/ (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Advani, R. Scaling Up Blended Financing of Water and Sanitation Investments in Kenya; WB Knowledge Note; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23996/K8812.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- The World Bank. Vietnam Water Sector Reform/Regulation—Review of Urban Water and Wastewater Utility Reform and Regulation; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/886931468125694191/pdf/ACS94240WP0P1496510Box385256B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- The World Bank (WB). Facilitated Access to Finance for Domestic Private Water Operators in Cambodia; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/680211472030707975/pdf/107972-BRI-P159188-BlendedFinanceCasesCambodia-PUBLIC.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2019).

- Winpenny, J.; Trémolet, S.; Cardone, R.; Kolker, J.; Kingdom, W.; Mountford, L. Aid Flows to the Water Sector, Overview and Recommendations; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/348721480583568708/Aid-flows-to-the-water-sector-overview-and-recommendations (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Project Preparation Committee (OECD). Good Practice in Project Preparation: Public Water Utilities. 2005. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/34723486.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Soppe, G.; Janson, N.M.; Piantini, S. Water Utility Turnaround Framework: A Guide for Improving Performance; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/515931542315166330/Water-Utility-Turnaround-Framework-A-Guide-for-Improving-Performance (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Global Water Intelligence (GWi). Creating Africa’s Most Bankable Water Utility Volume 20. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalwaterintel.com/global-water-intelligence-magazine/ (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- The World Bank. Uganda—Turnaround of the National Water and Sewerage Corporation. 2003. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9729 (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Rossum, S.; Hariram, P. Mobilising infrastructural investments through Water Operators’ Partnerships: An example from Mali. Presented at IRC WASH Debate, The Hague, The Netherlands. November 2018. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/ircuser/mobilizing-infrastructural-investments-through-water-operators-partnerships-an-example-from-mali (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- The World Bank. Kenya: Using Private Financing to Improve Water Services; WB Brief; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/partners/brief/kenya-using-private-financing-to-improve-water-services (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Water and Sanitation Program (WSP). Public-Private Partnership Stories Benin: Piped Water Supply Systems in Rural and Small Towns. 2015. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/949fa29d-6e60-4554-8194-a41b3f32b756/PPPStories_Benin_WSP.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- Lazarte, E.; Senior Water and Sanitation Advisor USAID. Personal communication, 8 February 2019.

- Marchese, N.; Conference discussion at 2018 Stockholm World Water Week, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Moise, I.; Barbee, M. Azure: Mobilizing technical services and financial capital to improve water services for small communities in Latin America. Conference presentation; Stockholm, Sweden. 28 August 2018. Available online: https://water.org/globalfinance2018/ and https://www.crs.org/media-center/news-release/crs-and-idbmif-announce-partnership-azure-blended-finance-facility (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Water and Sanitation Program (WSP). Lenders’ Manual for Commercial Financing of the Water and Sanitation Sector in Kenya; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.wsp.org/sites/wsp.org/files/publications/WSP-Lenders-Toolkit-Commercial-Financing-Water-Sanitation-Kenya.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Ndiso, J.; Malalo, H. Kenya’s Parliament Approves Retaining Interest Rate Cap, Against IMF Wishes; Reuters: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-kenya-economy/kenyas-parliament-approves-retaining-interest-rate-cap-against-imf-wishes-idUKKCN1LF1L4 (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Smiet, F. Catalysing WASH: From Possible to profitable; an overview. In Proceedings of the IRC WASH Debate, The Hague, The Netherlands, November 2018; Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/ircuser/catalyzing-wash-from-possible-to-profitable-an-overview (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Steel, W.F.; Darteh, B. Strategies for Household Sanitation: Ghana’s Experience with Output-based Aid and Implementation of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area Sanitation & Water Project; Consultant report prepared for the Global Partnership for Output-based Aid (GPOBA) and the Ghana Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resources; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pories, L.; Fonseca, C.; Delmon, V. Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right. Water 2019, 11, 2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112425

Pories L, Fonseca C, Delmon V. Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right. Water. 2019; 11(11):2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112425

Chicago/Turabian StylePories, Lesley, Catarina Fonseca, and Victoria Delmon. 2019. "Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right" Water 11, no. 11: 2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112425

APA StylePories, L., Fonseca, C., & Delmon, V. (2019). Mobilising Finance for WASH: Getting the Foundations Right. Water, 11(11), 2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112425