Shift of Sediments Bacterial Community in the Black-Odor Urban River during In Situ Remediation by Comprehensive Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sites and In Situ Remediation Description

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Analysis of Physicochemical Parameters

2.4. DNA Extraction and Illumina Miseq Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

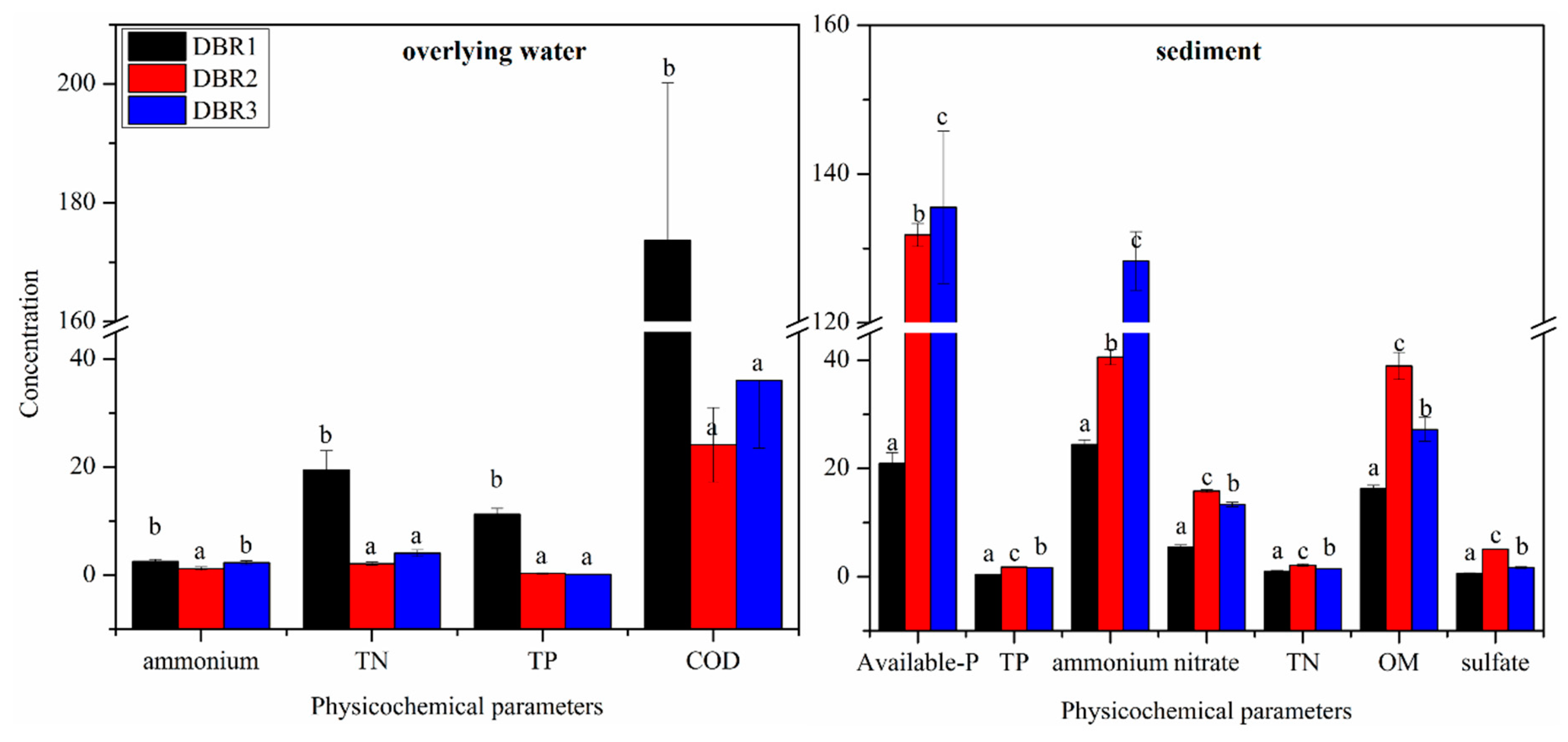

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters of the Overlying Water and Sediment among Different Restoration Stages

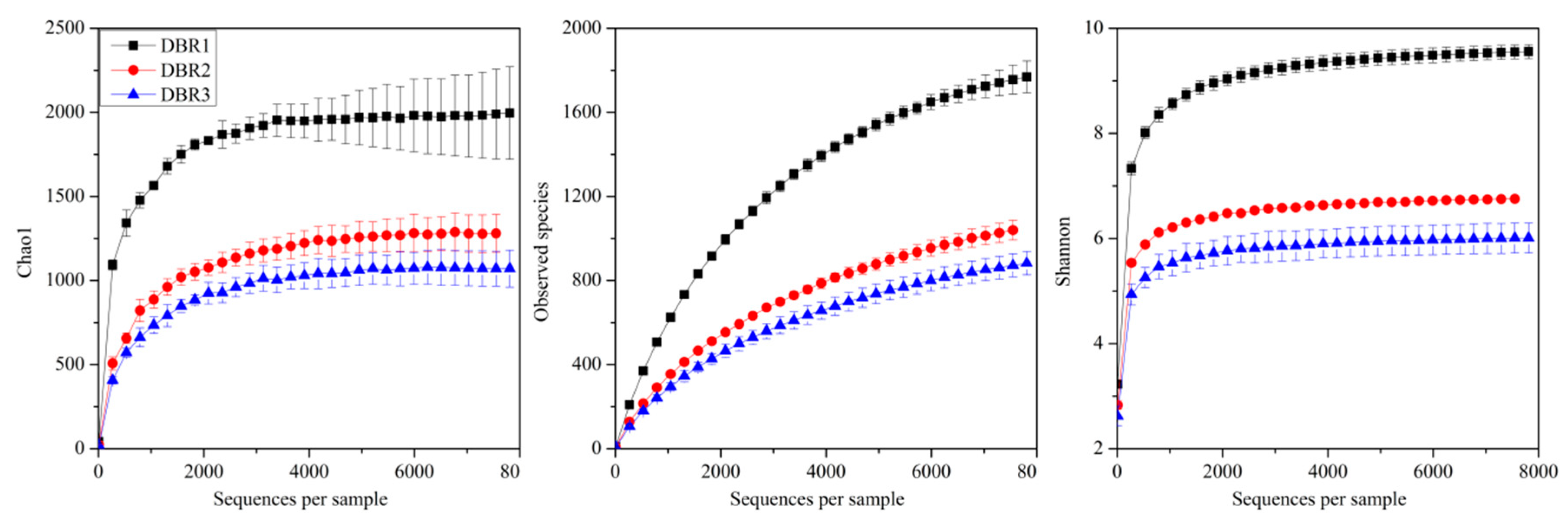

3.2. Rarefaction Curves of Bacteria among Different Restoration Stages

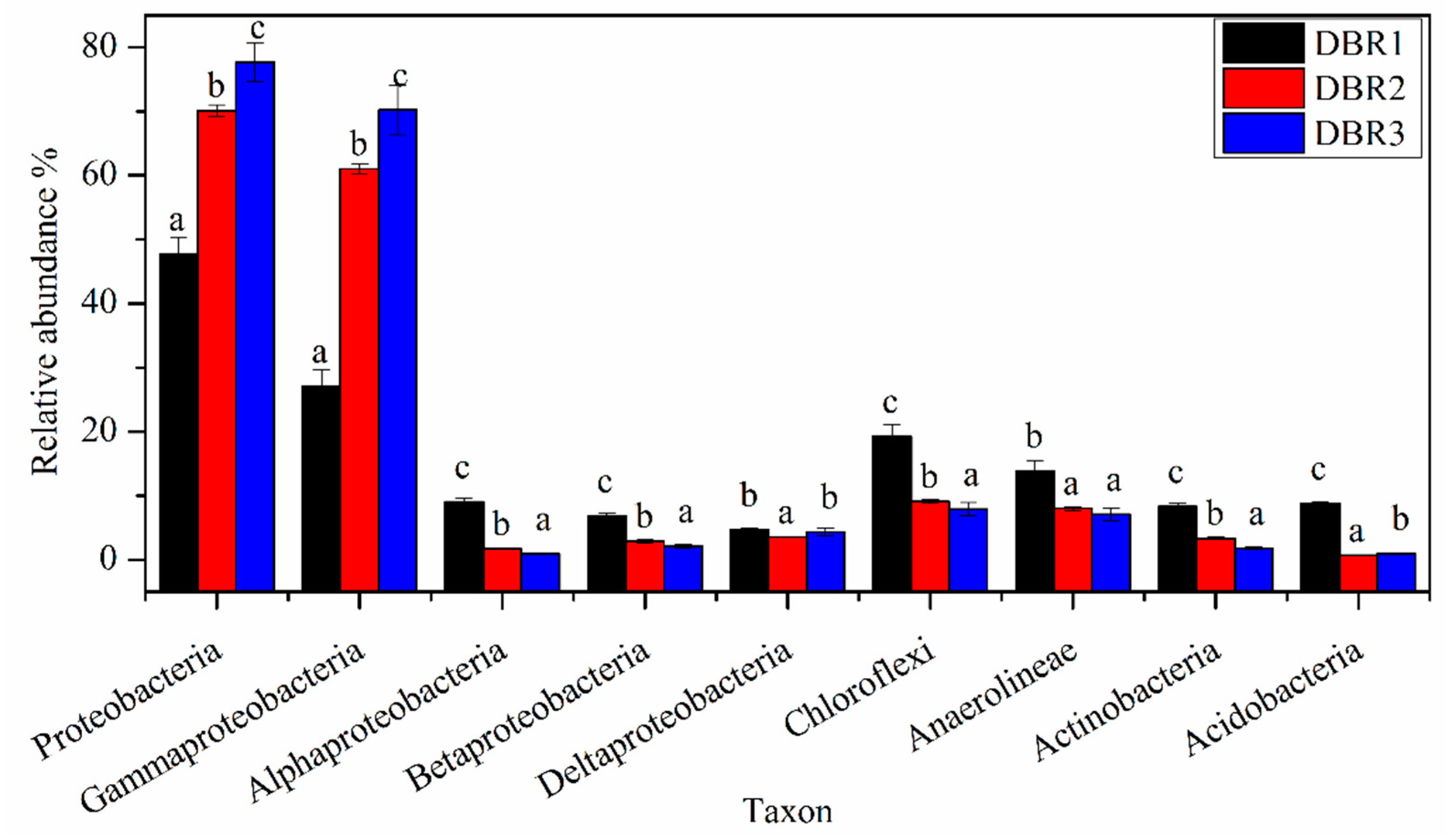

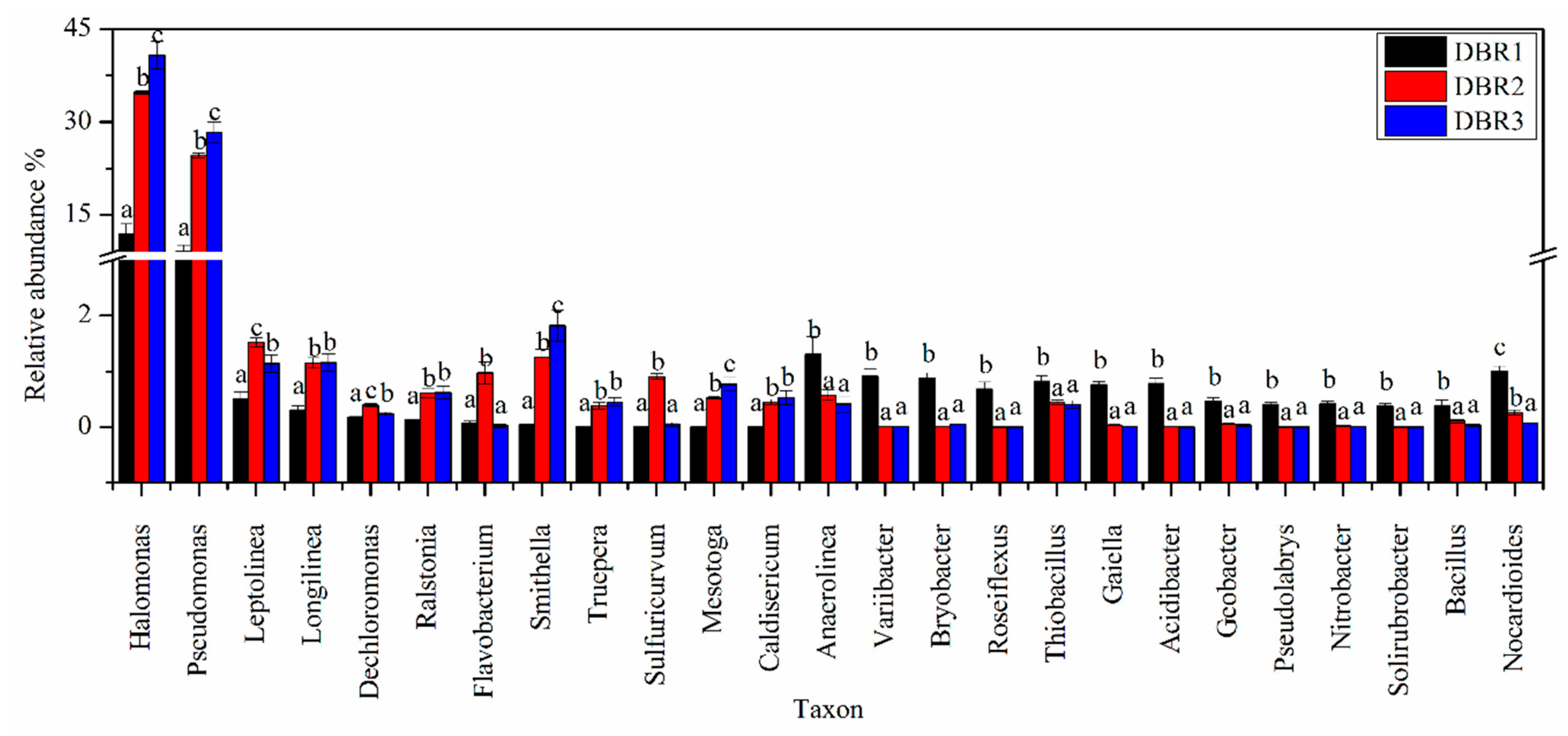

3.3. Microbial Community Composition among Different Restoration Stages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M.; He, J.; Zheng, Z. Black-odor water analysis and heavy metal distribution of Yitong River in Northeast China. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 2051–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, L.F.; Niu, L.; Zhang, W. Vertical distribution and assemblages of microbial communities and their potential effects on sulfur metabolism in a black-odor urban river. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 235, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, R.; Chasteen, T.G. Environmental VOSCs-formation and degradation of dimethyl sulfide, methanethiol and related materials. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginzburg, B.; Dor, I.; Chalifa, I.; Hadas, O.; Lev, O. Formation of dimethyloligosulfides in Lake Kinneret: Biogenic formation of inorganic oligosulfide intermediates under oxic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Lin, H.; Yin, W.Z.; Shao, S.C.; Lv, S.H.; Hu, Y.Y. Water Quality and Microbial Community Changes in an Urban River after Micro-Nano Bubble Technology In Situ Treatment. Water 2019, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, E.; Langlet, D.; Viollier, E.; Koron, N.; Riedel, B.; Stachowitsch, M.; Faganeli, J.; Tharaud, M.; Geslin, E.; Jorissen, F. Artificially induced migration of redox layers in a coastal sediment from the Northern Adriatic. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Siegert, M.; Fang, W.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, F.; Lu, H.; Chen, G.-H.; Wang, S. Blackening and odorization of urban rivers: A bio-geochemical process. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.E.; Carter, L.J.; Kolpin, D.W.; Thomas-Oates, J.; Aba, B. Temporal and spatial variation in pharmaceutical concentrations in an urban river system. Water Res. 2018, 137, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Zhang, F.H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, L.Z.; Yin, D.Q.; Cheng, S.P. Experimental Study on Combined Bio-carrier for Pretreatment of Black Odor River Water. China Water Wastewater 2012, 28, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. Remediation of DDT and Its Metabolites in Contaminated Sediment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.P.; Zhang, S.K.; Zhang, L.Y.; Li, X.G.; Wang, F.; Li, G.W.; Li, J.X.; Li, W. In-situ remediation of sediment by calcium nitrate combined with composite microorganisms under low-DO regulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uggetti, E.; Hughes-Riley, T.; Morris, R.H.; Newton, M.L.; Trabi, C.L.; Hawes, P.; Puigagut, J.; García, J. Intermittent aeration to improve wastewater treatment efficiency in pilot-scale constructed wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, T.; Shao, M.F.; Fang, H. Autotrophic denitrification in nitrate-induced marine sediment remediation and Sulfurimonas denitrificans-like bacteria. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelo, L.W. Review: In situ and bioremediation of organic pollutants in aquatic sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Hu, J.Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, H.W.; Zhang, X.H. Profiling of microbial community during in situ remediation of volatile sulfide compounds in river sediment with nitrate by high throughput sequencing. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2013, 85, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.G.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.F. Application of calcium peroxide in water and soil treatment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 337, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Xie, Y.B.; Hashim, S.; Khan, A.A.; Wang, X.L.; Xu, H.Y. Application of Microbial Technology Used in Bioremediation of Urban Polluted River: A Case Study of Chengnan River, China. Water 2018, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.L.; Hu, Z.B.; Liang, Y.C.; Lu, H.; Liu, K.H.; Jiang, Z. Experimental study on remediation of sediments in urban black-odorous rivers by denitrifying bacteria. Environ. Eng. 2015, 33, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.L.; Xu, Z.Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, R.R.; Zhou, A.C. Pilot-scale Study on In-situ Reduction of Black and Odorous Sediment in River Channel by Immobilized Microorganism Technology. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wobus, A.; Bleul, C.; Maassen, S.; Scheerer, C.; Schuppler, M.; Jacobs, E.; Röske, I. Microbial diversity and functional characterization of sediments from reservoirs of different trophic state. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 46, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.K.; Bai, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.L.; Qi, M.Y.; Ma, X.D.; Wang, H.; Kong, D.Y.; Wang, A.J.; Liang, B. Bioremediation of contaminated urban river sediment with methanol stimulation: Metabolic processes accompanied with microbial community changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.F.; Chen, R.R.; Zhu, E.H.; Chen, N.; Yang, B.; Shi, H.H. Toxicity bioassays for water from black-odor rivers in Wenzhou, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. Influence of biochar on heavy metals and microbial community during composting of river sediment with agricultural wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.L.; Lei, M.T.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.N.; Xu, C.; Niu, L.H.; Wang, L.F.; et al. Determination of vertical and horizontal assemblage drivers of bacterial community in a heavily polluted urban river. Water Res. 2019, 161, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Environmental Protection Administration of China. Monitor and Analysis Method of Water and Wastewater, 4th ed.; Chinese Environmental Science Publication House: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.K. Analytical Methods of Soil Agrochemistry; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 146–195. [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.J.; Nabout, J.C.; Farjalla, V.F.; Lopes, P.M.; Bozelli, R.L.; Huszar, V.L.M.; Roland, F. Environmental factors driving phytoplankton taxonomic and functional diversity in Amazonian floodplain lakes. Hydrobiologia 2017, 802, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, C.; Villeneuve, F.; Alabouvette, C.; Edel-Hermann, V.; Mateille, T.; Steinberg, C. Soil health through soil disease suppression: Which strategy from descriptors to indicators? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sheng, H.F.; He, Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.X.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Zhou, H.W. Comparison of the Levels of Bacterial Diversity in Freshwater, Intertidal Wetland, and Marine Sediments by Using Millions of Illumina Tags. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8264–8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, P.; Fardeau, M.L.; Joseph, M.; Guasco, S.; Hamaide, F.; Biasutti, S.; Michotey, V.; Bonin, P.; Ollivier, B. Isolation and characterization of Thermanaerothrix daxensis gen. nov.; sp. nov.; a thermophilic anaerobic bacterium pertaining to the phylum “Chloroflexi”, isolated from a deep hot aquifer in the Aquitaine Basin. Syst. Appl. Microbial. 2011, 34, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwart, G.; Crump, B.; Agterveld, M.P.K.V.; Hagen, F.; Han, S.K. Typical freshwater bacteria: An analysis of available 16S rRNA gene sequences from plankton of lakes and rivers. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2002, 28, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.T.; Encarnación, M.; Ostos, J.C.; Ventosa, A. Halomonas organivorans sp nov.; a moderate halophile able to degrade aromatic compounds. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Ruan, X.H.; Wang, J.; Shi, X. Spatial and seasonal variations in the abundance of nitrogen-transforming genes and the microbial community structure in freshwater lakes with different trophic satuses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, C.; Yan, C.; Guan, W.; Liu, J. Comparison of Iris pseudacorus wetland systems with unplanted systems on pollutant removal and microbial community under nanosilver exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Q.G.; Hu, J. Dynamic Change in Enzyme Activity and Bacterial Community with long-term rice Cultivation in Mudflats. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.X.; Han, Y.X.; Xu, C.Y.; Han, H.J. Enhanced biodegradation of coal gasification wastewater with anaerobic biofilm on polyurethane (PU), powdered activated carbon (PAC), and biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, M.Q.; Yin, Q.D.; Wu, G.X. Inhibition mitigation and ecological mechanism of mesophilic methanogenesis triggered by supplement of ferroferric oxide in sulfate-containing systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.K.; Li, C.; Wang, H.J.; Chen, W.L.; Huang, Q.Y. Characterization of a phenanthrene-degrading microbial consortium enriched from petrochemical contaminated environment. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2016, 115, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.S.; Goh, K.M.; Chan, C.S.; Annie Tan, G.Y.; Yin, W.F.; Chong, C.S.; Chan, K.G. Microbial diversity of thermophiles with biomass deconstruction potential in a foliage-rich hot spring. Microbiologyopen 2018, 7, e00615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhen, S.; Heng, S.; Wu, J. Effects of the combination of aeration and biofilm technology on transformation of nitrogen in black-odor river. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Kou, Z.; Teng, X.; Cai, W.; Hu, J. Shift of Sediments Bacterial Community in the Black-Odor Urban River during In Situ Remediation by Comprehensive Measures. Water 2019, 11, 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102129

Zhang J, Tang Y, Kou Z, Teng X, Cai W, Hu J. Shift of Sediments Bacterial Community in the Black-Odor Urban River during In Situ Remediation by Comprehensive Measures. Water. 2019; 11(10):2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102129

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jian, Yun Tang, Zhanguo Kou, Xiao Teng, Wei Cai, and Jian Hu. 2019. "Shift of Sediments Bacterial Community in the Black-Odor Urban River during In Situ Remediation by Comprehensive Measures" Water 11, no. 10: 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102129

APA StyleZhang, J., Tang, Y., Kou, Z., Teng, X., Cai, W., & Hu, J. (2019). Shift of Sediments Bacterial Community in the Black-Odor Urban River during In Situ Remediation by Comprehensive Measures. Water, 11(10), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102129