Evaluating the Effectiveness of Combined Indoor Air Quality Management and Asthma Education on Indoor Air Quality and Asthma Control in Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACQ | Asthma Control Questionnaire |

| AQLQ | Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter ≤ 2.5 μm |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| tVOC | Total Volatile Organic Compounds |

| HEPA | High-Efficiency Particulate Air |

References

- Vos, T.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, C.A.; Zahran, H.S. The status of asthma in the United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Percentage of Asthma Episode in the Past 12 Months for Adults Aged 18 and Over, United States, 2019–2024. National Health Interview Survey. 2025. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult/index.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Gaffney, A.; Himmelstein, D.U.; Woolhandler, S. Asthma disparities in the United States narrowed during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a national survey, 2019 to 2022. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merghani, M.M.; Mohmmed, R.G.A.; Al-Sayaghi, K.M.; Alshamrani, N.S.M.; Awadalkareem, E.M.; Shaaib, H.; Alharbi, A.; AlKaabi, A.; Faqihi, S.; Abdalla, A.; et al. Asthma-related school absenteeism: Prevalence, disparities, and the need for comprehensive management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dialogues Health 2025, 7, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmagambetov, T.; Kuwahara, R.; Garbe, P. The economic burden of asthma in the United States, 2008–2013. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Lung Association. Asthma. 2023. Available online: https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/asthma (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Paterson, C.A.; Sharpe, R.A.; Taylor, T.; Morrissey, K. Indoor PM2.5, VOCs and asthma outcomes: A systematic review in adults and their home environments. Environ. Res. 2021, 202, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, D.L.; Le, K.M.; Truong, D.D.; Le, H.T.; Trinh, T.H. Environmental allergen reduction in asthma management: An overview. Front. Allergy 2003, 4, 1229238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breysse, P.N.; Diette, G.B.; Matsui, E.C.; Butz, A.M.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C. Indoor air pollution and asthma in children. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, E.C.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C.; Rusher, R.; Breysse, P.N.; Diette, G.B. Asthma in the inner city and the indoor environment. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2008, 28, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jie, Y.; Ismail, N.H.; Jie, X.; Isa, Z.M. Do indoor environments influence asthma and asthma-related symptoms among adults in homes? A review of the literature. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2011, 110, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanchongkittiphon, W.; Mendell, M.J.; Gaffin, J.M.; Wang, G.; Phipatanakul, W. Indoor environmental exposures and exacerbation of asthma: An update to the 2000 review by the Institute of Medicine. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diette, G.B.; McCormack, M.C.; Hansel, N.N.; Breysse, P.N.; Matsui, E.C. Environmental issues in managing asthma. Respir. Care 2008, 53, 602–617. [Google Scholar]

- Sublett, J.L. Effectiveness of air filters and air cleaners in allergic respiratory diseases: A review of the recent literature. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011, 11, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Raja, S.; Ferro, A.R.; Jaques, P.A.; Hopke, P.K.; Gressani, C.; Wetzel, L.E. Effectiveness of heating, ventilation and air conditioning system with HEPA filter unit on indoor air quality and asthmatic children’s health. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drieling, R.L.; Sampson, P.D.; Krenz, J.E.; Tchong French, M.I.; Jansen, K.L.; Massey, A.E.; Farquhar, S.A.; Min, E.; Perez, A.; Riederer, A.M.; et al. Randomized trial of a portable HEPA air cleaner intervention to reduce asthma morbidity among Latino children in an agricultural community. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, J.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Ahsan, Z.; Bilal, M.; Fatima, S.S. Effect of high-efficiency particulate air filter on children with asthma: A systematic review protocol of RCTs. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, L.S.; Phipatanakul, W. Environmental remediation in the treatment of allergy and asthma: Latest updates. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.; Takaro, T.K.; Song, L.; Beaudet, N.; Edwards, K. A randomized controlled trial of asthma self-management support comparing clinic-based nurses and in-home community health workers: The Seattle–King County Healthy Homes II Project. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.; Huang, K.; Conner, L.; Tapangan, N.; Xu, X.; Carrillo, G. Effects of the home-based educational intervention on health outcomes among primarily Hispanic children with asthma: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, G.; Roh, T.; Baek, J.; Chong-Menard, B.; Ory, M. Evaluation of Healthy South Texas Asthma Program on improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities among the underserved Hispanic population: Using the RE-AIM model. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rangel, A.; Baek, J.; Roh, T.; Xu, X.; Carrillo, G. Assessing impact of household intervention on indoor air quality and health of children with asthma in the US-Mexico border: A pilot study. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 6042146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Rangel, A.; Roh, T.; Wang, T.; Baek, J.; Conner, L.; Carrillo, G. Reviewing the impact of indoor air quality management and asthma education on asthmatic children’s health outcomes—A pilot study. In Proceedings of the Healthy Buildings Europe 2021, Oslo, Norway, 21–23 June 2021; Available online: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/82999/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Muanprasong, S.; Aqilah, S.; Hermayurisca, F.; Taneepanichskul, N. Effectiveness of Asthma Home Management Manual and Low-Cost Air Filter on Quality of Life Among Asthma Adults: A 3-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2613–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rangel, A.; Musau, T.S.; McGill, G. Field evaluation of a low-cost indoor air quality monitor to quantify exposure to pollutants in residential environments. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 2018, 7, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousan, S.; Koehler, K.; Hallett, L.; Peters, T.M. Evaluation of consumer monitors to measure particulate matter. J. Aerosol Sci. 2017, 107, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, E.F.; Buist, A.S.; Cox, F.M.; Ferrie, P.J.; King, D.R. Validation of a standardized version of the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Chest 1999, 115, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, E.F.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Guyatt, G.H.; Ferrie, P.J.; King, D.R. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur. Respir. J. 1999, 14, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, G.; Spence, E.; Lucio, R.B.C.; Smith, K. Improving asthma in Hispanic families through a home-based educational intervention. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2015, 28, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Hand, D.W.; Perram, D.L.; Taylor, R. Investigation of the Treatability of the Primary Indoor Volatile Organic Compounds on Activated Carbon Fiber Cloths at Typical Indoor Concentrations. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2009, 59, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khararoodi, M.G.; Haghighat, F.; Lee, C.S. Develop and validate a mathematical model to estimate the removal of indoor VOCs by carbon filters. Build. Environ. 2023, 233, 110082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, J.; Kraakman, N.J.R.; Pérez, C.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. A state-of-the-art review on indoor air pollution and strategies for indoor air pollution control. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butz, A.M.; Matsui, E.C.; Breysse, P.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Eggleston, P.; Diette, G.; Williams, D.A.; Yuan, J.; Bernert, J.T.; Rand, C. A randomized trial of air cleaners and a health coach to improve indoor air quality for inner-city children with asthma and secondhand smoke exposure. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 741–748. [Google Scholar]

- Riederer, A.M.; Krenz, J.E.; Tchong-French, M.I.; Torres, E.; Perez, A.; Younglove, L.R.; Jansen, K.L.; Hardie, D.C.; Farquhar, S.A.; Sampson, P.D.; et al. Effectiveness of portable HEPA air cleaners on reducing indoor PM2.5 and NH3 in an agricultural cohort of children with asthma: A randomized intervention trial. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 454–466. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Batterman, S.; Parker, E.; Godwin, C.; Chin, J.Y.; O’Toole, A.; Robins, T.; Brakefield-Caldwell, W.; Lewis, T. Particle concentrations and effectiveness of free-standing air filters in bedrooms of children with asthma in Detroit, Michigan. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2303–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.; Song, L.; Philby, M. Community health worker home visits for adults with uncontrolled asthma: The HomeBASE Trial randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, W.J.; Crain, E.F.; Gruchalla, R.S.; O’Connor, G.T.; Kattan, M.; Evans, R., III; Stout, J.; Malindzak, G.; Smartt, E.; Plaut, M.; et al. Results of a home-based environmental intervention among urban children with asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- James, C.; Bernstein, D.I.; Cox, J.; Ryan, P.; Wolfe, C.; Jandarov, R.; Newman, N.; Indugula, R.; Reponen, T. HEPA filtration improves asthma control in children exposed to traffic-related airborne particles. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (median (IQR) | 23 (20, 30) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 25 (83%) |

| Male | 5 (17%) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 15 (50%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1 (3.3%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (17%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or mixed | 8 (27%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (3.3%) |

| Education | |

| High School | 4 (13%) |

| >High School | 24 (80%) |

| Did not respond | 2 (6.7%) |

| Income | |

| <$75,000 | 19 (63%) |

| ≥$75,000 | 8 (27%) |

| Did not respond | 3 (10%) |

| Characteristic | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Air quality indicators 1 | ||

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) | 21.32 (1.74) | 18.19 (1.76) |

| tVOC (ppb) | 237.05 (1.28) | 251.81 (1.29) |

| Temperature (°F) | 71.7 (2.8) | 71.9 (4.3) |

| Relative humidity (%) | 55.7 (6.3) | 55.6 (6.2) |

| Asthma health outcomes 2 | ||

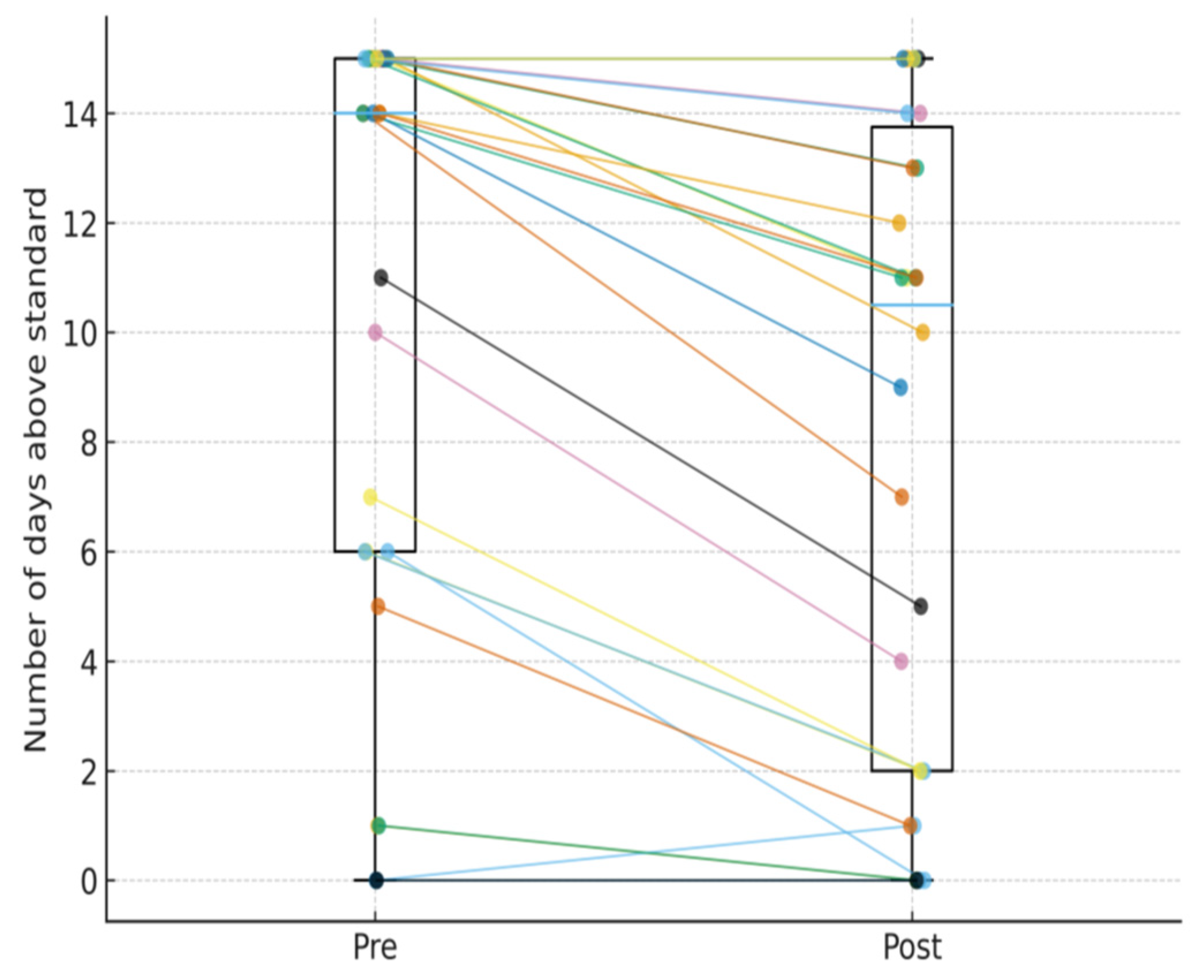

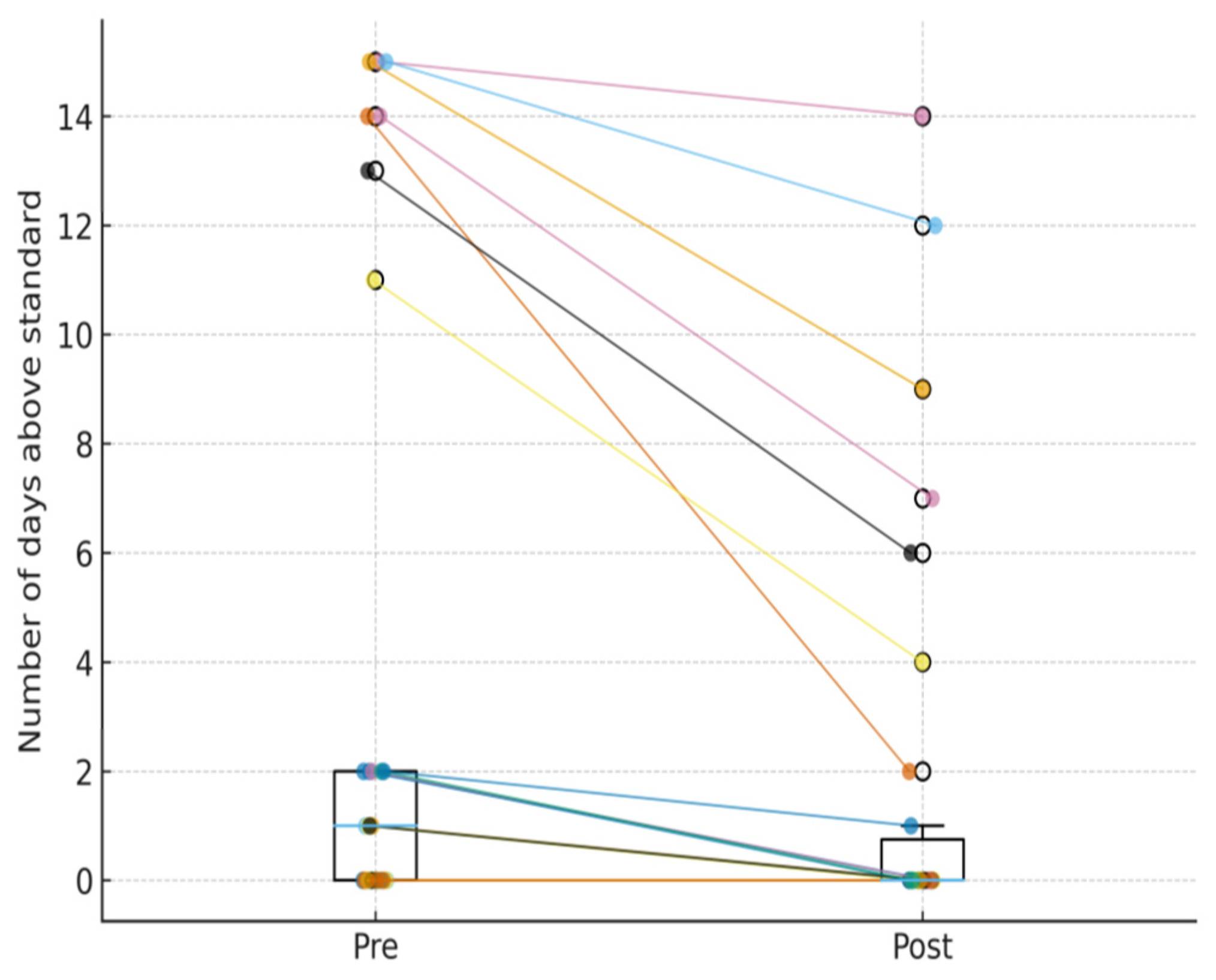

| Well-controlled asthma (≤0.75) | 9 (30%) | 20 (66.7%) |

| Partially controlled asthma (0.76–1.5) | 13 (43.3%) | 7 (23.3%) |

| Poorly controlled asthma (>1.5) | 8 (26.7%) | 3 (10%) |

| ACQ score 3 | 1.17 (0.67, 1.67) | 0.50 (0.33, 0.83) |

| AQLQ score 3 | 5.75 (5.19, 6.41) | 6.30 (6.16, 6.81) |

| Characteristic | Pre-Post Mean Difference (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| ACQ score | −0.52 (−0.76–−0.27) | <0.001 |

| AQLQ score | 0.58 (0.35–0.81) | <0.001 |

| PM2.5 | −3.62 (−5.46–−1.78) | <0.001 |

| tVOC | 16.29 (1.93–30.65) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Obeng, A.; Roh, T.; Moreno-Rangel, A.; Carrillo, G. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Combined Indoor Air Quality Management and Asthma Education on Indoor Air Quality and Asthma Control in Adults. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010084

Obeng A, Roh T, Moreno-Rangel A, Carrillo G. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Combined Indoor Air Quality Management and Asthma Education on Indoor Air Quality and Asthma Control in Adults. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleObeng, Alexander, Taehyun Roh, Alejandro Moreno-Rangel, and Genny Carrillo. 2026. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Combined Indoor Air Quality Management and Asthma Education on Indoor Air Quality and Asthma Control in Adults" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010084

APA StyleObeng, A., Roh, T., Moreno-Rangel, A., & Carrillo, G. (2026). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Combined Indoor Air Quality Management and Asthma Education on Indoor Air Quality and Asthma Control in Adults. Atmosphere, 17(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010084