Evaluation of WRF Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes for Dry Season Conditions over Complex Terrain in the Liangshan Prefecture, Southwestern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

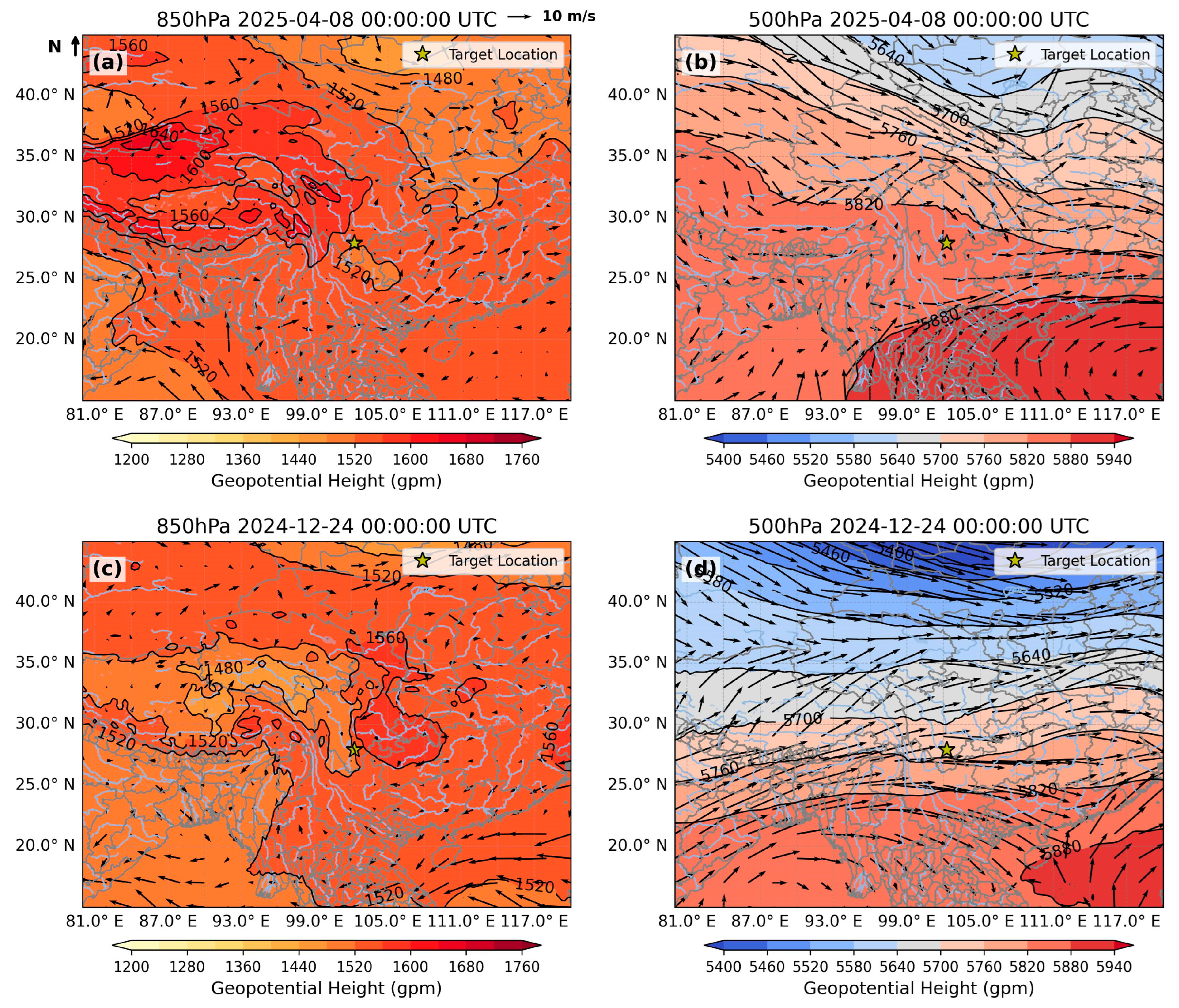

2.1. Description of Case Study

2.2. Numerical Model Description

2.3. PBL Schemes

2.3.1. Asymmetrical Convective Model Version 2 (ACM2) Scheme

2.3.2. Bougeault–Lacarrère (BL) Scheme

2.3.3. Mellor–Yamada–Janjic (MYJ) Scheme

2.3.4. Mellor–Yamada–Nakanishi–Niino Level 2.5 (MYNN2.5) Scheme

2.3.5. Quasi-Normal Scale Elimination (QNSE) Scheme

2.3.6. Yonsei University (YSU) Scheme

2.4. Observation Data

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

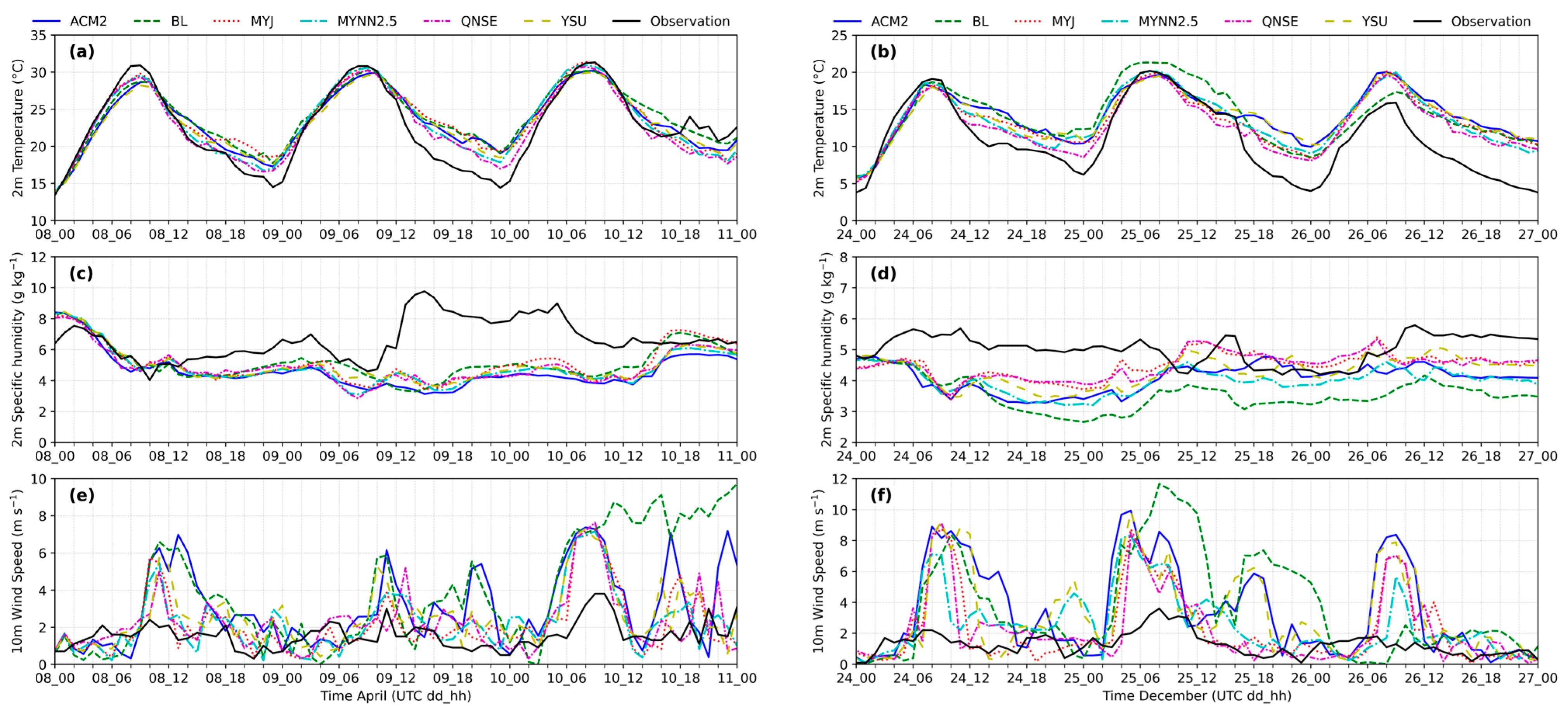

3.1. Diurnal Evolution of Surface Meteorological Parameters

3.2. Surface Flux

3.3. Vertical Profile

3.4. Planetary Boundary Layer Height

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Garratt, J.R.; Pielke, R.A. On the sensitivity of mesoscale models to surface-layer parameterization constants. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 1989, 48, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, J.R. Review: The atmospheric boundary layer. Earth Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Zhang, X. The role of the planetary boundary layer parameterization schemes on the meteorological and aerosol pollution simulations: A review. Atmos. Res. 2020, 239, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, X.; Huang, W. A Comparison of Boundary Layer Characteristics Simulated Using Different Parametrization Schemes. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2016, 161, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.E.; Cavallo, S.M.; Coniglio, M.C.; Brooks, H.E. A Review of Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes and Their Sensitivity in Simulating Southeastern U.S. Cold Season Severe Weather Environments. Weather Forecast. 2015, 30, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Dudhia, J. Evaluation of PBL Parameterizations in WRF at Subkilometer Grid Spacings: Turbulence Statistics in the Dry Convective Boundary Layer. Mon. Weather Rev. 2016, 144, 1161–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díez, M.; Fernández, J.; Fita, L.; Yagüe, C. Seasonal dependence of WRF model biases and sensitivity to PBL schemes over Europe. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 139, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Qiao, F.; Liang, X.Z.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Y. High-resolution Simulation of an Extreme Heavy Rainfall Event in Shanghai Using the Weather Research and Forecasting Model: Sensitivity to Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Lei, Y.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of typical planetary boundary layer (PBL) parameterization schemes in China—Part 1: Understanding expressiveness of schemes for different regions from the mechanism perspective. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 6635–6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, B.; Chen, G.; Li, Y. Simulation performance of planetary boundary layer schemes in WRF v4.3.1 for near-surface wind over the western Sichuan Basin: A single-site assessment. Geosci. Model Dev. 2025, 18, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, K.B.; Srinivas, C.V.; Singh, A.B.; Rao, S.V.; Baskaran, R.; Venkatraman, B. Numerical simulation and intercomparison of boundary layer structure with different PBL schemes in WRF using experimental observations at a tropical site. Atmos. Res. 2014, 145, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-M.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W.; Zhang, F. Evaluation of Three Planetary Boundary Layer Schemes in the WRF Model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1831–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Hong, S.-Y. Intercomparison of Planetary Boundary Layer Parametrizations in the WRF Model for a Single Day from CASES-99. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2011, 139, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumos, A.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Zittis, G.; Constantinidou, K.; Tzyrkalli, A.; Lelieveld, J. Evaluation of WRF Model Boundary Layer Schemes in Simulating Temperature and Heat Extremes over the Middle East–North Africa (MENA) Region. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2023, 62, 1315–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, N.; Ojha, N.; Dimri, A.P.; Singh, R.S. Impacts of different boundary layer parameterization schemes on simulation of meteorology over Himalaya. Atmos. Res. 2024, 298, 107154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Solanki, R.; Ojha, N.; Janssen, R.H.; Pozzer, A.; Dhaka, S.K. Boundary layer evolution over the central Himalayas from radio wind profiler and model simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 10559–10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, R.F.; Baldasano, J.M. Impact of WRF model PBL schemes on air quality simulations over Catalonia, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, R.F.; Tiana-Alsina, J.; Baldasano, J.M.; Rocadenbosch, F.; Papayannis, A.; Solomos, S.; Tzanis, C.G. Sensitivity of Boundary Layer variables to PBL schemes in the WRF model based on surface meteorological observations, lidar, and radiosondes during the HygrA-CD campaign. Atmos. Res. 2016, 176–177, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Mejía, L.; Hoyos, C.D. Characterization of the atmospheric boundary layer in a narrow tropical valley using remote-sensing and radiosonde observations and the WRF model: The Aburrá Valley case-study. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 145, 2641–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-F.; Wang, Y.; Xian, T.; Tian, G.; Lu, C.; Mao, X.; Wang, L.P. Impact of PBL schemes on multiscale WRF modeling over complex terrain, Part I: Mesoscale simulations. Atmos. Res. 2024, 297, 107117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Farley, R.D.; Orville, H.D. Bulk Parameterization of the Snow Field in a Cloud Model. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 1983, 22, 1065–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.S. The Kain–Fritsch Convective Parameterization: An Update. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2004, 43, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhia, J. Numerical Study of Convection Observed during the Winter Monsoon Experiment Using a Mesoscale Two-Dimensional Model. J. Atmos. Sci. 1989, 46, 3077–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.J.; Mlawer, E.J.; Clough, S.A.; Morcrette, J.J. Impact of an improved longwave radiation model, RRTM, on the energy budget and thermodynamic properties of the NCAR community climate model, CCM3. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000, 105, 14873–14890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noilhan, J.; Planton, S. A Simple Parameterization of Land Surface Processes for Meteorological Models. Mon. Weather Rev. 1989, 117, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleim, J.E. A Combined Local and Nonlocal Closure Model for the Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Part II: Application and Evaluation in a Mesoscale Meteorological Model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2007, 46, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleim, J.E.; Xiu, A. Development and Testing of a Surface Flux and Planetary Boundary Layer Model for Application in Mesoscale Models. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1995, 34, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleim, J.E. A Combined Local and Nonlocal Closure Model for the Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Part I: Model Description and Testing. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2007, 46, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougeault, P.; Lacarrere, P. Parameterization of Orography-Induced Turbulence in a Mesobeta-Scale Model. Mon. Weather Rev. 1989, 117, 1872–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Mellor, G. A Simulation of the Wangara Atmospheric Boundary Layer Data. J. Atmos. Sci. 1975, 32, 2309–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janić, Z.I. Nonsingular Implementation of the Mellor-Yamada Level 2.5 Scheme in the NCEP Meso Model; NOAA: Camp Springs, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Janjić, Z.I. The Step-Mountain Eta Coordinate Model: Further Developments of the Convection, Viscous Sublayer, and Turbulence Closure Schemes. Mon. Weather Rev. 1994, 122, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Niino, H. An Improved Mellor–Yamada Level-3 Model with Condensation Physics: Its Design and Verification. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2004, 112, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukoriansky, S.; Galperin, B.; Perov, V. Application of a New Spectral Theory of Stably Stratified Turbulence to the Atmospheric Boundary Layer over Sea Ice. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2005, 117, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Noh, Y.; Dudhia, J. A New Vertical Diffusion Package with an Explicit Treatment of Entrainment Processes. Mon. Weather Rev. 2006, 134, 2318–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y. A new stable Boundary Layer mixing scheme and its impact on the simulated East Asian summer monsoon. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 136, 1481–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molod, A.; Salmun, H.; Dempsey, M. Estimating planetary boundary layer heights from NOAA profiler network wind profiler data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2015, 32, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmun, H.; Josephs, H.; Molod, A. GRWP-PBLH: Global Radar Wind Profiler Planetary Boundary Layer Height Data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1044–E1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastula, E.-M.; Galperin, B.; Dudhia, J.; LeMone, M.A.; Sukoriansky, S.; Vihma, T. Methodical assessment of the differences between the QNSE and MYJ PBL schemes for stable conditions. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 141, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J.C.; Delgado, R.; Berkoff, T.A.; Hoff, R.M. Determination of Planetary Boundary Layer Height on Short Spatial and Temporal Scales: A Demonstration of the Covariance Wavelet Transform in Ground-Based Wind Profiler and Lidar Measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, S.A.; Angevine, W.M. Boundary Layer Height and Entrainment Zone Thickness Measured by Lidars and Wind-Profiling Radars. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2000, 39, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PBL Scheme | Surface Layer Schemes | Closure | PBLH Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACM2 | Revised MM5 Scheme | Hybrid 1.0 non-local and local closure scheme | Rib = 0.25 |

| BL | Revised MM5 Scheme | 1.5 local | TKE = 0.005 m2·s−2 |

| MYJ | Eta similarity | 1.5 local | TKE = 0.1 m2·s−2 |

| MYNN2.5 | MYNN Scheme | 1.5 local | TKE = 1.0 × 10−6 m2·s−2 |

| QNSE | QNSE Scheme | 1.5 local | TKE = 0.01 m2·s−2 |

| YSU | Revised MM5 Scheme | 1.0 non-local | Rib = 0.25 (stable), 0 (unstable) |

| (April, December) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | ACM2 | BL | MYJ | MYNN2.5 | QNSE | YSU |

| T2(°C) | ||||||

| RMSE | 2.32, 4.25 | 2.52, 3.83 | 2.51, 3.60 | 1.97, 3.51 | 1.79, 2.98 | 2.32, 4.19 |

| MBE | 0.78, 3.22 | 1.27, 3.12 | 1.05, 2.59 | 0.63, 2.71 | 0.10, 1.89 | 0.57, 3.01 |

| R | 0.91, 0.83 | 0.92, 0.90 | 0.90, 0.87 | 0.93, 0.90 | 0.94, 0.89 | 0.91, 0.81 |

| Q2(g kg−1) | ||||||

| RMSE | 2.70, 1.18 | 2.32, 1.58 | 2.33, 0.86 | 2.50, 1.20 | 2.44, 0.88 | 2.41, 0.97 |

| MBE | −2.03, −0.95 | −1.50, −1.47 | −1.54, −0.55 | −1.82, −1.03 | −1.78, −0.55 | −1.68, −0.72 |

| R | −0.11, −0.22 | −0.09, 0.30 | 0.002, −0.21 | −0.02, 0.004 | −0.002, −0.31 | −0.08, −0.03 |

| WS10(m s−1) | ||||||

| RMSE | 2.40, 3.48 | 3.62, 3.71 | 1.46, 2.34 | 1.50, 2.19 | 1.47, 2.22 | 1.70, 3.18 |

| MBE | 1.49, 2.19 | 2.37, 2.33 | 0.57, 0.98 | 0.67, 1.31 | 0.68, 0.97 | 0.98, 1.94 |

| R | 0.42, 0.47 | 0.41, 0.52 | 0.58, 0.55 | 0.54, 0.57 | 0.51, 0.52 | 0.51, 0.38 |

| April | PBL Scheme | RMSE | MBE | R | December | RMSE | MBE | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBLH (daytime) | ACM2 | 585.02 | 10.75 | 0.820 | PBLH (daytime) | 656.01 | −374.79 | 0.397 |

| BL | 526.32 | −107.28 | 0.840 | 745.40 | −605.15 | 0.493 | ||

| MYJ | 914.23 | −729.45 | 0.535 | 657.83 | −435.42 | 0.422 | ||

| MYNN2.5 | 532.85 | −72.92 | 0.778 | 624.58 | −396.21 | 0.397 | ||

| QNSE | 621.94 | −12.26 | 0.639 | 669.46 | 238.68 | 0.507 | ||

| YSU | 611.32 | −446.26 | 0.791 | 811.21 | −658.40 | 0.400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhong, J.; Su, D.; Zheng, Z.; Kong, W.; Fang, P.; Mo, F. Evaluation of WRF Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes for Dry Season Conditions over Complex Terrain in the Liangshan Prefecture, Southwestern China. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010053

Zhong J, Su D, Zheng Z, Kong W, Fang P, Mo F. Evaluation of WRF Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes for Dry Season Conditions over Complex Terrain in the Liangshan Prefecture, Southwestern China. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Jinhua, Debin Su, Zijun Zheng, Wenyu Kong, Peng Fang, and Fang Mo. 2026. "Evaluation of WRF Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes for Dry Season Conditions over Complex Terrain in the Liangshan Prefecture, Southwestern China" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010053

APA StyleZhong, J., Su, D., Zheng, Z., Kong, W., Fang, P., & Mo, F. (2026). Evaluation of WRF Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization Schemes for Dry Season Conditions over Complex Terrain in the Liangshan Prefecture, Southwestern China. Atmosphere, 17(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010053