Wide-Spectral-Range, Multi-Directional Particle Detection by the High-Energy Particle Detector on the FY-4B Satellite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Instrument

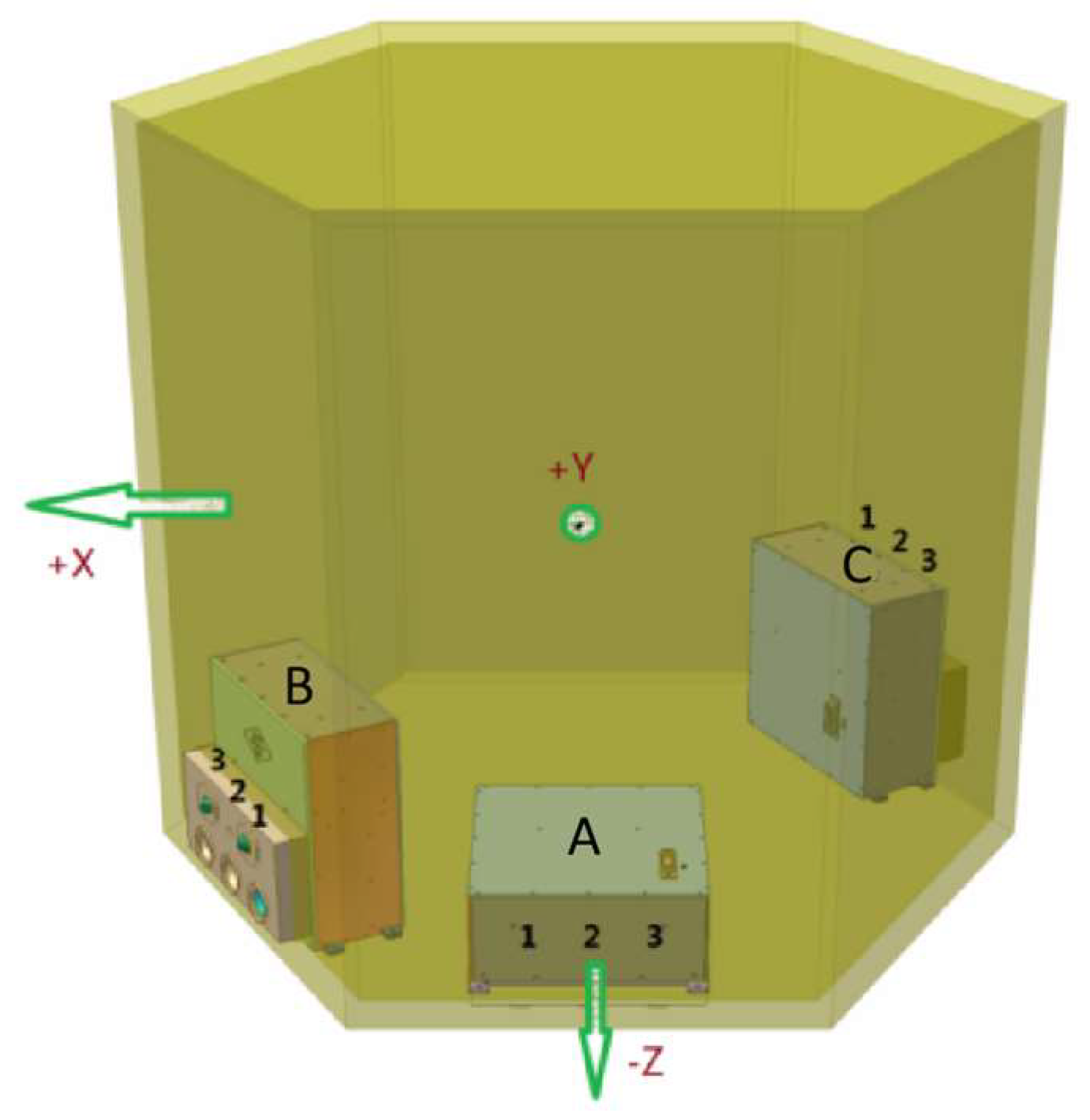

2.1. Load Layout and Field-of-View Coverage

2.2. Detection Principles of the HEPD

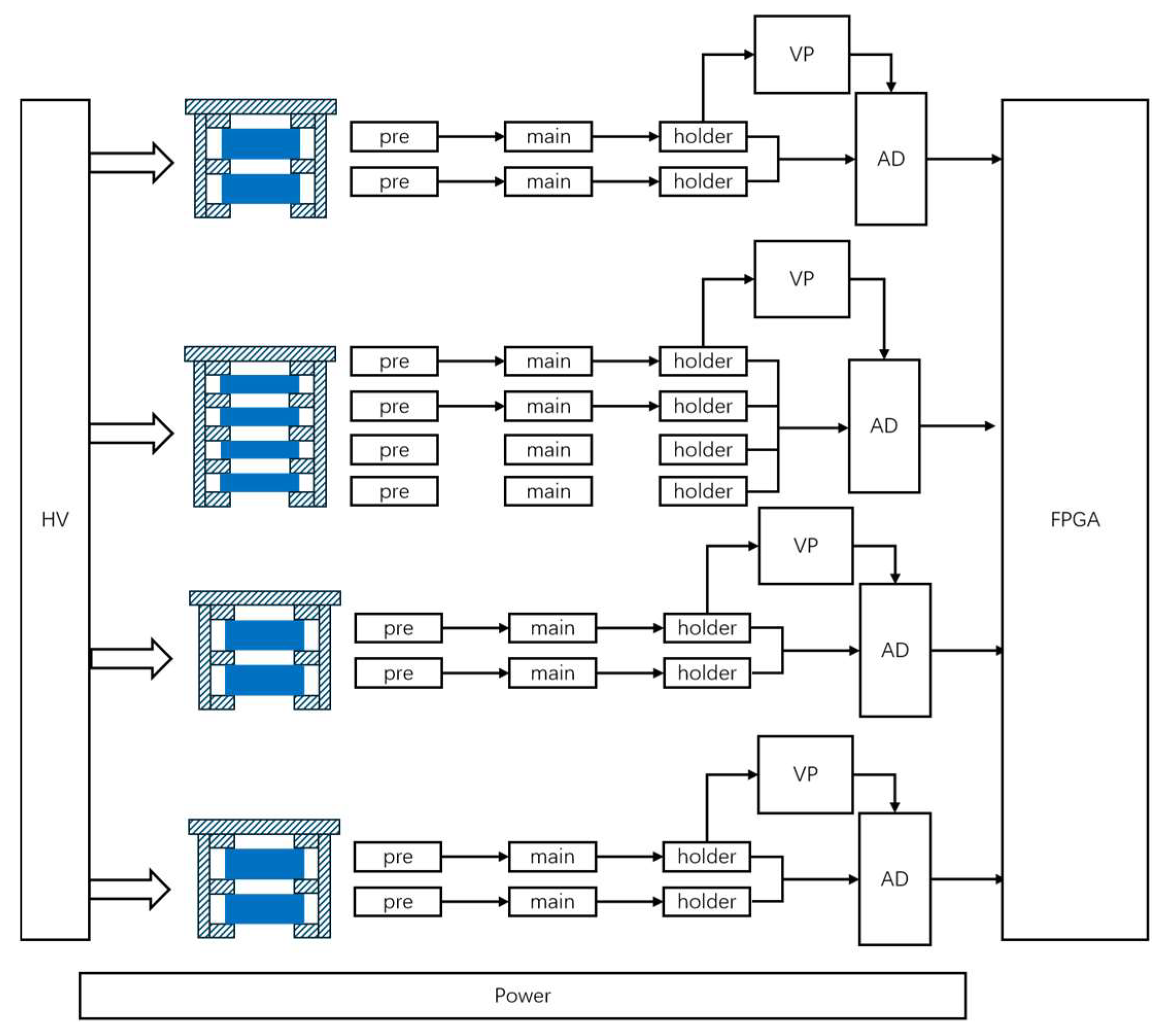

2.3. Electronic System

3. Ground Calibration

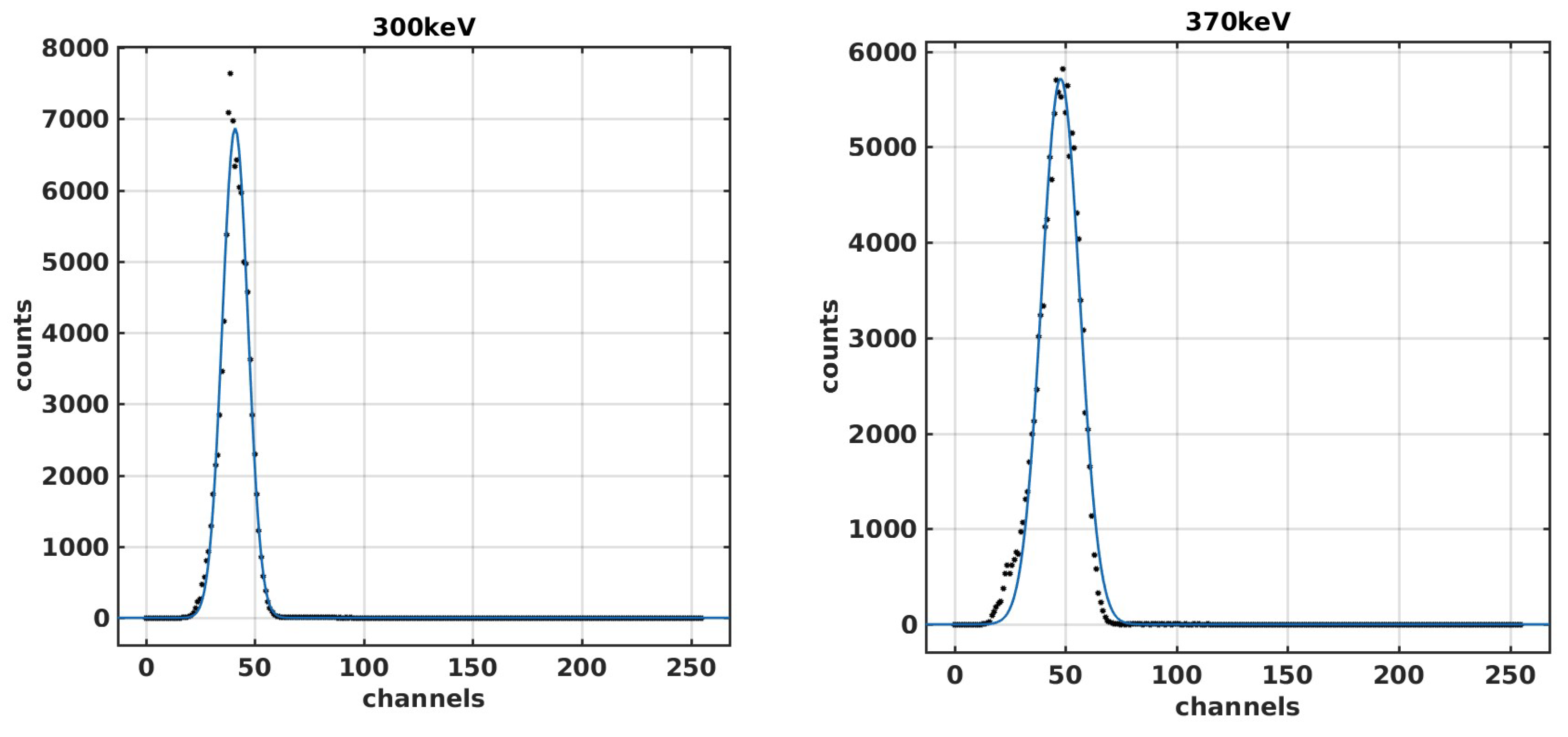

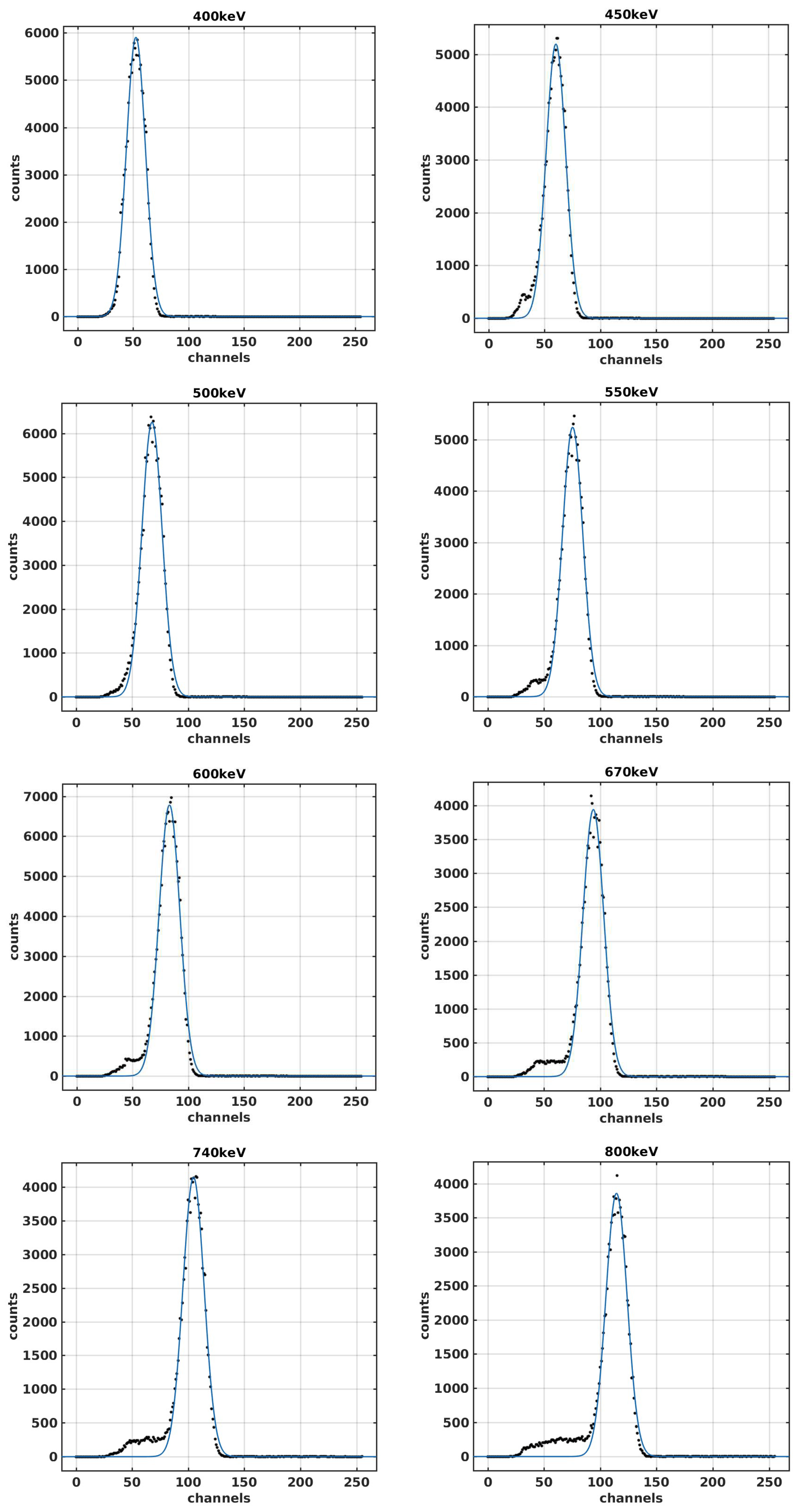

3.1. Energy Resolution and Energy Linearity

3.2. Angle Calibration

3.3. Results of Ground Calibration

4. Preliminary Observational Data and Results

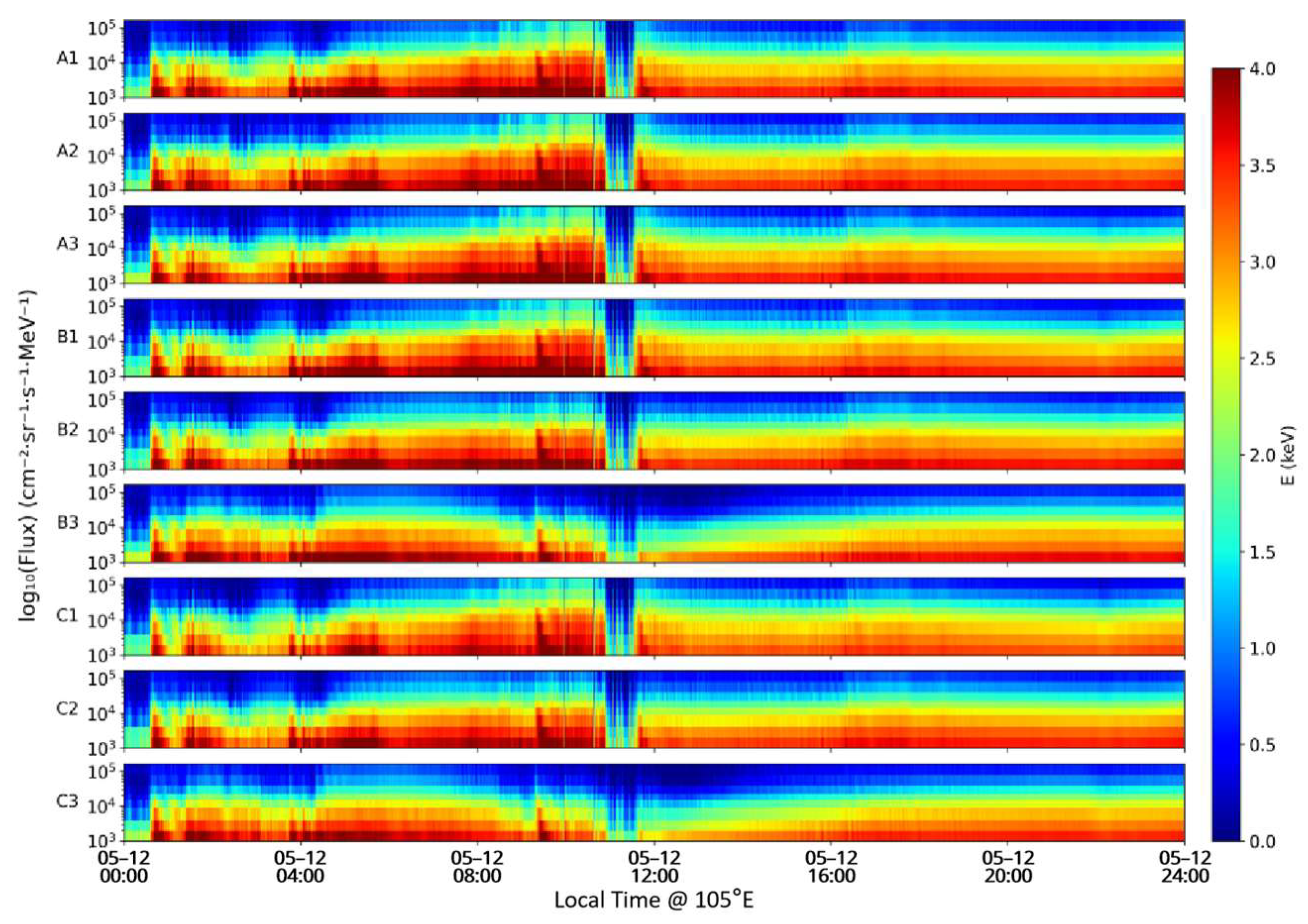

4.1. High-Energy Electrons and Geomagnetic Storm

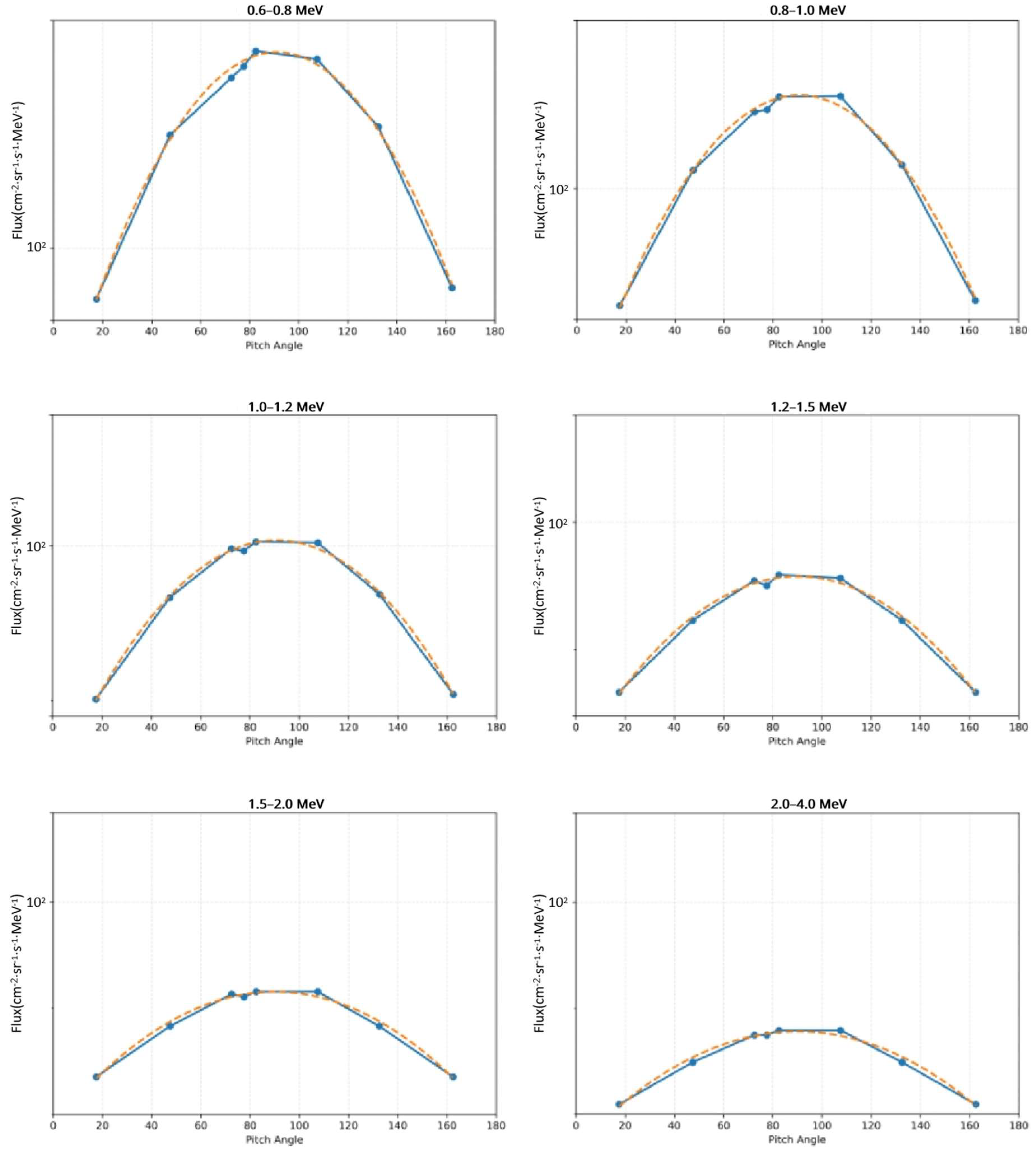

4.2. Pitch Angle Distribution of High-Energy Electrons

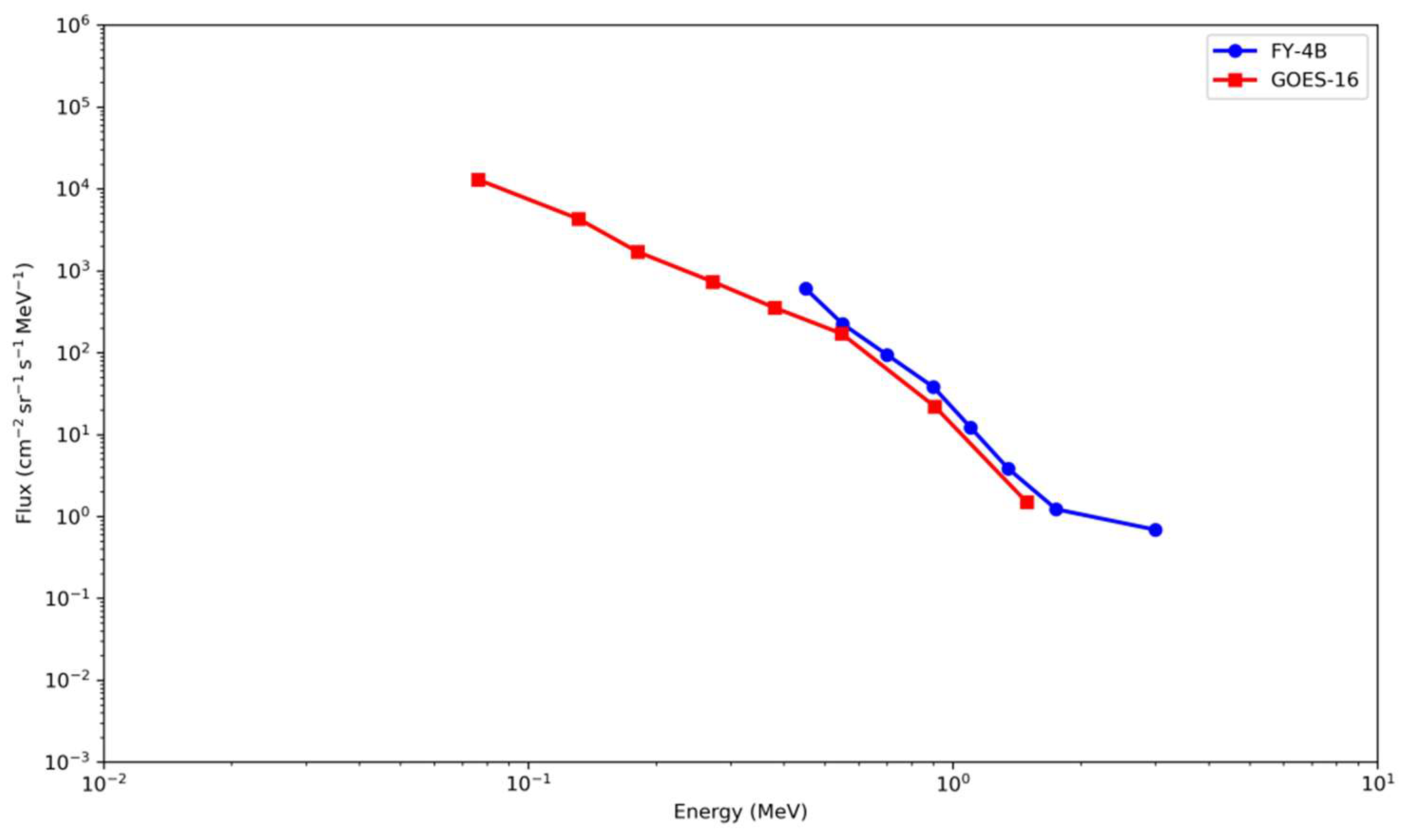

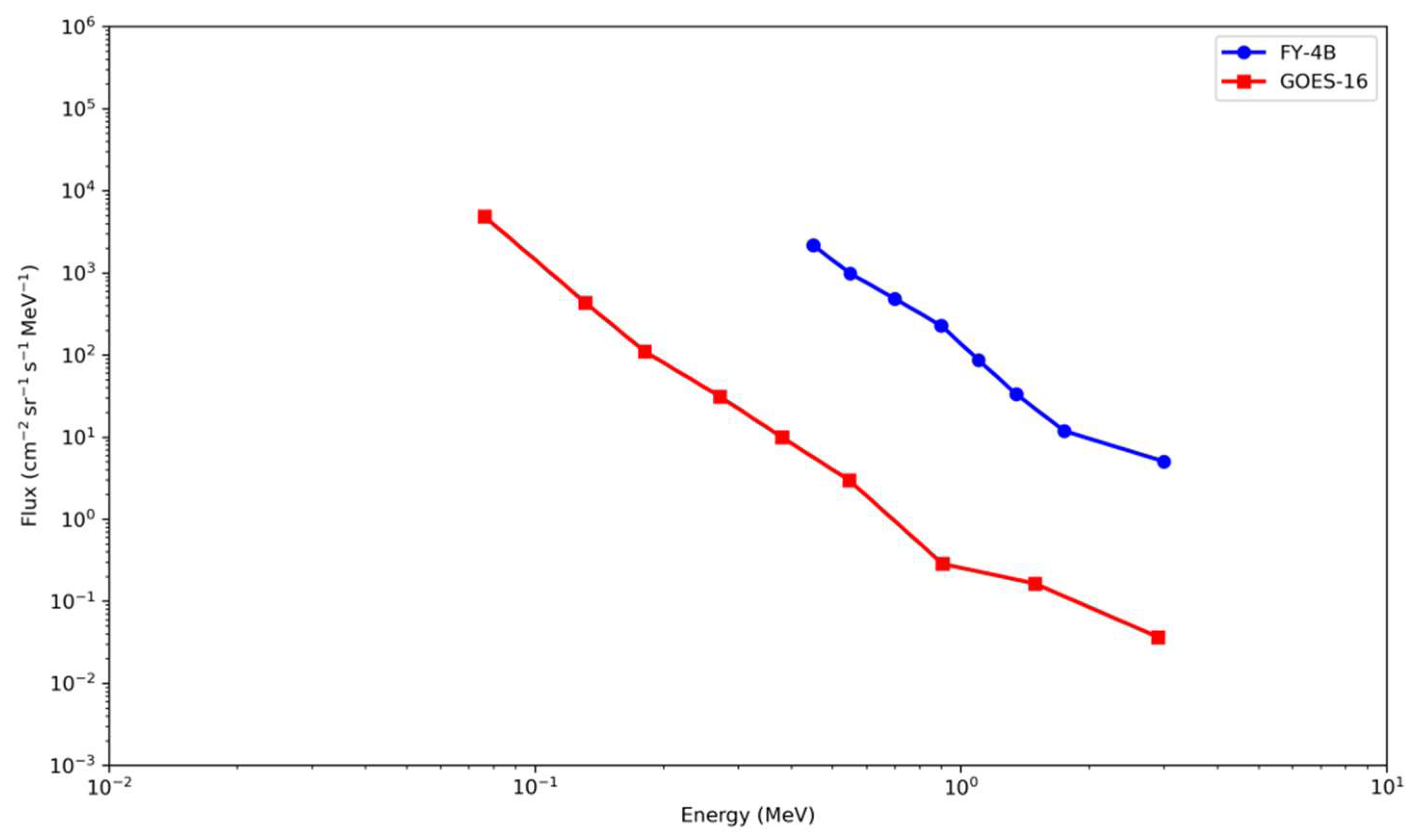

5. Comparison with GOES-16

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Wide-spectral-range and multi-directional capability: The FY-4B HEPD electron detector employs a stacked silicon telescope with a full-digital readout to measure energetic electrons over 0.4–4 MeV. Three identical units installed with different orientations provide nine look directions and an overall angular coverage close to 180°, enabling continuous monitoring of electron spectra, fluxes, and directional anisotropy at GEO.

- (2)

- Ground calibration demonstrates quantitative measurement capability: Accelerator calibrations show (i) good energy linearity suitable for quantitative spectral inversion and (ii) an energy resolution better than ~16% above 1 MeV. The directional response of each look direction is well characterized, with an angular-response FWHM of ~20° (full cone ~40°).

- (3)

- Stable in-orbit operation under both quiet and storm conditions: The HEPD provides continuous GEO monitoring with stable performance and uninterrupted data coverage. The in-orbit example in May 2024 clearly resolves flux variations, differential spectral evolution, and directional anisotropy, including the storm-time dropout and subsequent enhancement of energetic electrons.

- (4)

- Directional observations enable pitch angle diagnostics (local pitch angle): Using single-direction measurements and a geomagnetic field model, we derived local pitch angle distributions for 0.5–2.0 MeV electrons. Under quiet dayside conditions, the anisotropy is strongest between pitch angles near 90° and those near 0°/180°, and the contrast is more pronounced at lower energies.

- (5)

- Cross-validation against GOES-16 supports measurement reliability: Comparisons with GOES-16/SEISS in overlapping energy bands show generally consistent flux levels and spectral behavior during quiet periods. During geomagnetic storms, both missions capture the characteristic dropout–recovery–enhancement pattern, supporting the reliability and cross-mission comparability of FY-4B HEPD electron measurements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lanzerotti, L.J.; Breglia, C.; Maurer, D.W.; Johnson, G.K., III; Maclennan, C.G. Studies of spacecraft charging on a geosynchronous telecommunications satellite. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.N. The occurrence of operational anomalies in spacecraft and their relationship to space weather. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2002, 28, 2007–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, G.D. Relativistic electrons and magnetic storms: 1992–1995. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 1817–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.L.; Boteler, D.H.; Burlton, B.; Evans, J. Anik-E1 and E2 satellite failures of January 1994 revisited. Space Weather 2012, 10, S10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.F.; Allen, J.H. Spacecraft and ground anomalies related to the October–November 2003 solar activity. Space Weather 2004, 2, S03008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loto’aniu, T.M.; Singer, H.J.; Rodriguez, J.V.; Green, J.; Denig, W.; Biesecker, D.; Angelopoulos, V. Space weather conditions during the Galaxy 15 spacecraft anomaly. Space Weather 2015, 13, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, G.D.; McAdams, K.L.; Friedel, R.H.W.; O’brien, T.P. Acceleration and loss of relativistic electrons during geomagnetic storms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, T.P.; McPherron, R.L.; Sornette, D.; Reeves, G.D.; Friedel, R.; Singer, H.J. Which magnetic storms produce relativistic electrons at geosynchronous orbit? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2001, 106, 15533–15544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shprits, Y.Y.; Subbotin, D.; Ni, B. Evolution of electron fluxes in the outer radiation belt computed with the VERB code. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2009, 114, A11209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, Y.; Shinohara, I.; Takashima, T.; Asamura, K.; Higashio, N.; Mitani, T.; Kasahara, S.; Yokota, S.; Kazama, Y.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Geospace exploration project ERG. Earth Planets Space 2018, 70, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.V.; Denton, M.H.; Henderson, M.G. On-orbit calibration of geostationary electron and proton flux observations for augmentation of an existing empirical radiation model. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J. GOES EPEAD Science-Quality Electron Fluxes Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; NOAA National Geophysical Data Center: Asheville, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, B.T.; Rodriguez, J.V.; Onsager, T.G. The GOES-R Space Environment In Situ Suite (SEISS): Measurement of Energetic Particles in Geospace; The Goes-R Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ginet, G.P.; O’Brien, T.P.; Huston, S.L.; Johnston, W.R.; Guild, T.B.; Friedel, R.; Lindstrom, C.D.; Roth, C.J.; Whelan, P.; Quinn, R.A.; et al. AE9, AP9 and SPM: New models for specifying the trapped energetic particle and space plasma environment. Space Sci. Rev. 2013, 179, 579–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jing, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, F.; Shen, G.; Huang, C.; et al. Analysis of observation data from the new generation high-energy charged particle detector on the FY2G satellite. Chin. J. Geophys. 2016, 59, 3148–3158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zong, W.; Chen, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Design and performance of the space environment in-situ suite on the FY-4B satellite. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 8270–8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Chan, A.A. Fully adiabatic changes in storm time relativistic electron fluxes. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1997, 102, 22107–22116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Charged particles | Electron |

| Energy range (MeV) | 0.4–4 MeV |

| Channel (MeV) | E1: 0.4–0.5 |

| E2: 0.5–0.6 | |

| E3: 0.6–0.8 | |

| E4: 0.8–1.0 | |

| E5: 1.0–1.2 | |

| E6: 1.2–1.5 | |

| E7: 1.5–2.0 | |

| E8: 2.0–4.0 | |

| Working temperature (°C) | −15~+35 |

| Energy consumption (W) | <5.2 |

| Unit size (mm) | 230 × 230 × 157 |

| Mass (kg) | 5.0 |

| Data interface | 73 kbps |

| Incident Energy/keV | Energy Loss | Channel ADC Values | Energy Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 292.6 | 41.08 | 33.67% |

| 370 | 363.5 | 47.88 | 42.11% |

| 400 | 393.5 | 52.58 | 38.25% |

| 450 | 443.7 | 60.23 | 34.06% |

| 500 | 494.2 | 67.77 | 31.28% |

| 550 | 543.3 | 75.48 | 28.08% |

| 600 | 594.4 | 83.15 | 26.29% |

| 670 | 664.5 | 93.89 | 23.16% |

| 740 | 734.6 | 104.8 | 21.24% |

| 800 | 794.7 | 114.5 | 19.37% |

| 870 | 864.7 | 125.1 | 18.07% |

| 940 | 934.7 | 136.1 | 17.25% |

| 1000 | 994.7 | 146 | 15.98% |

| 1100 | 1094.8 | 161.7 | 14.96% |

| 1200 | 1194.9 | 178.1 | 13.98% |

| 1300 | 1295 | 193.8 | 13.53% |

| 1400 | 1395 | 210.3 | 12.70% |

| 1500 | 1495 | 227.2 | 12.19% |

| Calibration Method | Calibration Item | Calibration Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron accelerator in CAS Radioactive source: 207Bi | Energy resolution | Direction | Energy linearity | Energy resolution |

| Direction 1 | 1.04% | 15.98% (@1000 keV) | ||

| Direction 2 | 0.57% | 14.43% (@1000 keV) | ||

| Direction 3 | 0.64% | 15.82% (@1000 keV) | ||

| Linearity | 1.04% | |||

| Angle calibration | 40° field angle at each direction, with an FWHM of ≈20° | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meng, Q.; Shen, G.; Wang, C.; Yu, Q.; Quan, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y. Wide-Spectral-Range, Multi-Directional Particle Detection by the High-Energy Particle Detector on the FY-4B Satellite. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010048

Meng Q, Shen G, Wang C, Yu Q, Quan L, Zhang H, Sun Y. Wide-Spectral-Range, Multi-Directional Particle Detection by the High-Energy Particle Detector on the FY-4B Satellite. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Qingwen, Guohong Shen, Chunqin Wang, Qinglong Yu, Lin Quan, Huanxin Zhang, and Ying Sun. 2026. "Wide-Spectral-Range, Multi-Directional Particle Detection by the High-Energy Particle Detector on the FY-4B Satellite" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010048

APA StyleMeng, Q., Shen, G., Wang, C., Yu, Q., Quan, L., Zhang, H., & Sun, Y. (2026). Wide-Spectral-Range, Multi-Directional Particle Detection by the High-Energy Particle Detector on the FY-4B Satellite. Atmosphere, 17(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010048