Understanding Motorcycle Emissions Across Their Technical, Behavioral, and Socioeconomic Determinants in the City of Kigali: A Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection, Study Area, and Sampling Methodology

- Engine capacity (cc): A primary determinant of fuel combustion and emission levels (e.g., 100–125 cc, 126–150 cc, 151–200 cc).

- Year of manufacture: A proxy for vehicle technology and degradation (e.g., pre-2015, 2015–2019, 2020–present).

- Operational zone: To account for potential geographical variations in usage patterns, maintenance culture, and fuel quality across Kigali’s major zones (Remera, Nyabugogo, and Camp Kigali).

- = required sample size;

- = Z-score (1.96 for a 95% confidence level);

- = estimated proportion of motorcycles with high emissions (conservatively set at 0.5 to maximize the sample size);

- = margin of error (5% or 0.05);

- = total population size (the estimated number of operational moto-taxis in Kigali).

2.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

Data Cleaning and Transformation

2.3. Descriptive and Exploratory Statistical Analysis of Variables Used

2.4. The MANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis H Test Models

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Exploratory Analysis of Variables Used

3.2. The MANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis H Test Results

3.3. Comparative Models Findings: MANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis H Tests

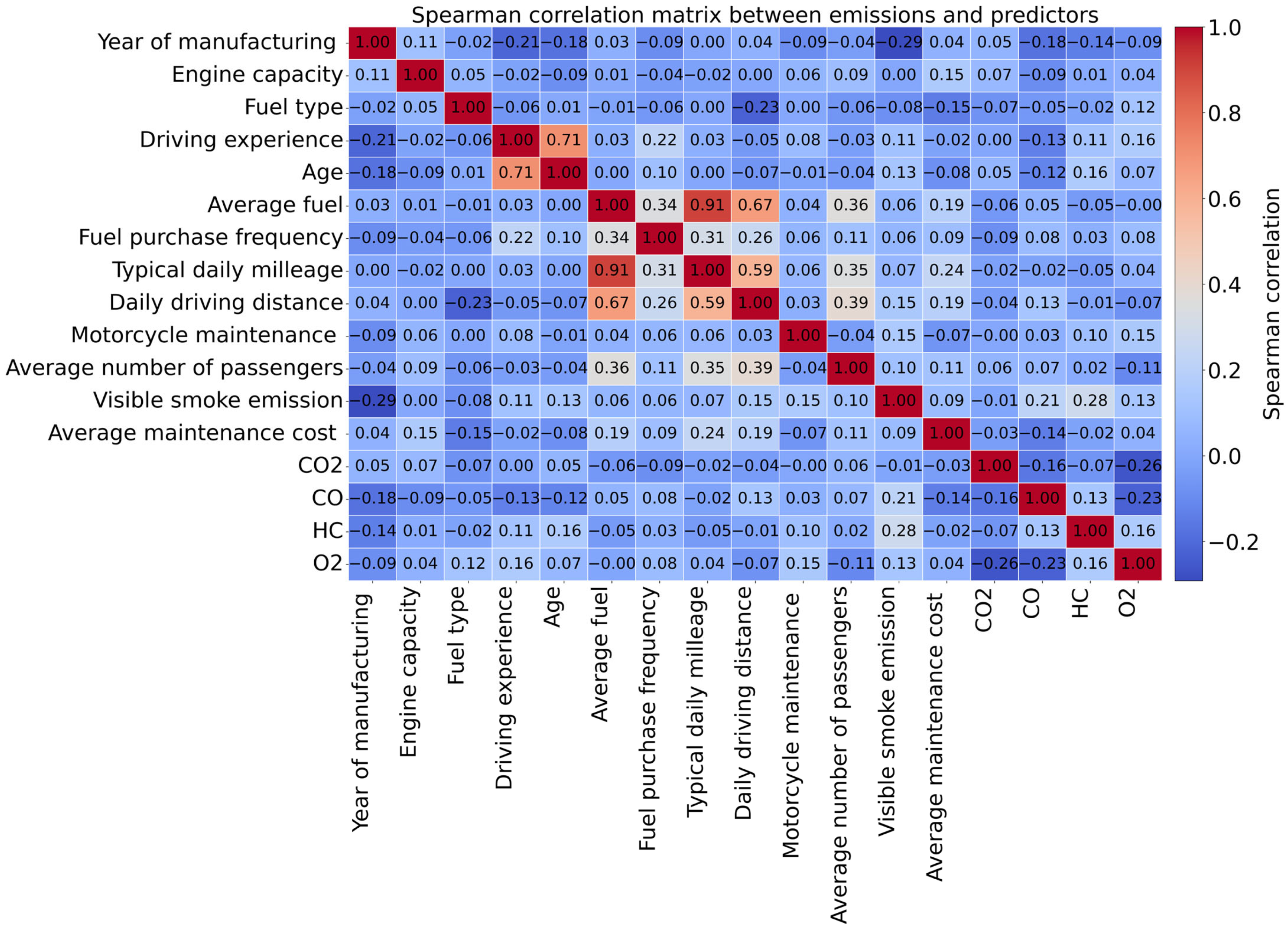

3.4. Bivariate Relationships Between Emissions and Predictors

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amegah, A.K.; Agyei-Mensah, S. Urban Air Pollution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Time for Action. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pochet, P.; Lesteven, G. The Spread of Motorcycles in Sub-Saharan Africa: Dynamics and Public Issues. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 3237–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehebrecht, D.; Heinrichs, D.; Lenz, B. Motorcycle-Taxis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Knowledge, Implications for the Debate on “Informal” Transport and Research Needs. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 69, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Olvera, L.; Plat, D.; Pochet, P. Looking for the Obvious: Motorcycle Taxi Services in Sub-Saharan African Cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimo, P.K.; Lartey-Young, G.; Agyeman, S.; Akintunde, T.Y.; Kyere-Gyeabour, E.; Krampah, F.; Awomuti, A.; Oderinde, O.; Agbeja, A.O.; Afolabi, O.G. Spatial Distribution and Policy Implications of the Exhaust Emissions of Two-Stroke Motorcycle Taxis: A Case Study of Southwestern State in Nigeria. J. Niger. Soc. Phys. Sci. 2024, 6, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Rathod, B.; Calzavara, J.; Courtright, T.; Sims, T.; Saint-Sernin, É.; Clack, H.; Jagger, P.; Craig, M. Emissions Impacts of Electrifying Motorcycle Taxis in Kampala, Uganda. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2022, 104, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiang, C.M.; Monkam, D.; Njeugna, E.; Gokhale, S. Projecting Impacts of Two-Wheelers on Urban Air Quality of Douala, Cameroon. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, T.; Behrens, R. The Role and Impact of Motorcycle-Taxis: A Systematic Review. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 89, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Truong, T.M.; Nguyen, M.H.; Pham, H.G.; Li, Z.C.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What Factors Influence the Intention to Use Electric Motorcycles in Motorcycle-Dominated Countries? An Empirical Study in Vietnam. Transp. Policy 2024, 146, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, A.M.; Weilenmann, M. Comparison of Real-World Emissions from Two-Wheelers and Passenger Cars. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisephane, I.; Zoltán, T. Environmental determinants of ambient air pollution in Urban East Africa: Unveiling critical insights from Kigali, Rwanda. Sci. Afr. 2025, 30, e03055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehebrecht, D. Motorcycle-Taxis in East African Cities: Growth Dynamics, Regulation, Challenges and Potentials. In Transport Planning and Mobility in Urban East Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimo, P.K.; Rahim, A.B.A.; Lartey-Young, G.; Ehebrecht, D.; Wang, L.; Ma, W. Investigating the Increasing Demand and Formal Regulation of Motorcycle Taxis in Ghana. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Olvera, L.; Guézéré, A.; Plat, D.; Pochet, P. Earning a Living, but at What Price? Being a Motorcycle Taxi Driver in a Sub-Saharan African City. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 55, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owino, F.; Peters, K.; Jenkins, J.; Opiyo, P.; Chetto, R.; Ntramah, S.; Marion Mutabazi, M.; Vincent, J.; Johnson, T.P.; Santos, R.T.; et al. The Urban Motorcycle Taxi Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: Needs, Practices and Equity Issues. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2024, 12, 2354400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Courtright, T.; Nkurunziza, A.; Lah, O. Motorcycle Taxis in Transition? Review of Digitalization and Electrification Trends in Selected East African Capital Cities. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 13, 101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koossalapeerom, T.; Satiennam, T.; Satiennam, W.; Leelapatra, W.; Seedam, A.; Rakpukdee, T. Comparative Study of Real-World Driving Cycles, Energy Consumption, and CO2 Emissions of Electric and Gasoline Motorcycles Driving in a Congested Urban Corridor. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Effects Institute. Traffic-Related Air Pollution: A Critical Review of the Literature on Emissions, Exposure, and Health Effects | Health Effects Institute. 2010. Available online: https://www.healtheffects.org/publication/traffic-related-air-pollution-critical-review-literature-emissions-exposure-and-health (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Sudmant, A.; Colenbrander, S.; Gouldson, A.; Chilundika, N. Private Opportunities, Public Benefits? The Scope for Private Finance to Deliver Low-Carbon Transport Systems in Kigali, Rwanda. Urban Clim. 2017, 20, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colenbrander, S.; Sudmant, A.; Chilundika, N.; Gouldson, A. The Scope for Low-Carbon Development in Kigali, Rwanda: An Economic Appraisal. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marija, J.; Amponsah, O.; Mensah, H.; Takyi, A.; Braimah, I. A View of Commercial Motorcycle Transportation in Sub-Saharan African Cities Through the Sustainable Development Lens. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2022, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irankunda, E.; Török, Z. Monitoring and Dispersion Modelling of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) in Rwanda. In Aerosol Science and Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sietchiping, R.; Permezel, M.J.; Ngomsi, C. Transport and Mobility in Sub-Saharan African Cities: An Overview of Practices, Lessons and Options for Improvements. Cities 2012, 29, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarpasand, O.; Talaie, M.R.; Ahmadikia, H.; Khozani, A.T.; Shalamzari, M.D.; Majidi, S. Real-World Evaluation of Driving Behaviour and Emission Performance of Motorcycle Transportation in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Isfahan, Iran. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P. Analysis of Air Pollution from Vehicle Emissions for the Contiguous United States. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2024, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kulshrestha, M.J.; Rani, N.; Kumar, K.; Sharma, C.; Aswal, D.K. An Overview of Vehicular Emission Standards. Mapan-J. Metrol. Soc. India 2023, 38, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.S.; Alkarkhi, A.F.M.; Bin Lalung, J.; Ismail, N. Water Quality of River, Lake and Drinking Water Supply in Penang State by Means of Multivariate Analysis. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 26, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rencher, A.C.; Christensen, W.F. Methods of Multivariate Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 0-470-17896-5. [Google Scholar]

- Okoye, K.; Hosseini, S. Mann–Whitney U Test and Kruskal–Wallis H Test Statistics in R. In R Programming: Statistical Data Analysis in Research; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Levy, J.I. Factors Influencing the Spatial Extent of Mobile Source Air Pollution Impacts: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduwayezu, G.; Manirakiza, V.; Mugabe, L.; Malonza, J.M. Urban Growth and Land Use/Land Cover Changes in the Post-Genocide Period, Kigali, Rwanda. Environ. Urban. Asia 2021, 12, S127–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduwayezu, G.; Kagoyire, C.; Zhao, P.; Eklund, L.; Pilesjo, P.; Bizimana, J.P.; Mansourian, A. Spatial Machine Learning for Exploring the Variability in Low Height-For-Age From Socioeconomic, Agroecological, and Climate Features in the Northern Province of Rwanda. GeoHealth 2024, 8, e2024GH001027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FORENSICS Forensics Detectors FD-600M Gas Analyzer Installation Guide. Available online: https://manuals.plus/forensics-detectors/fd-600m-gas-analyzer-manual (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- United Nations/ECE. Worldwide Harmonized Motorcycle Emissions Certification Procedure (WMTC): Technical Report/: Transmitted by the Expert from Germany. 2004. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/521702?ln=en&v=pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Nduwayezu, G.; Mansourian, A.; Bizimana, J.P.; Pilesjö, P. Hybridizing Spatial Machine Learning to Explore the Fine-Scale Heterogeneity between Stunting Prevalence and Its Associated Risk Determinants in Rwanda. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.F.A.; Corrêa, S.M.; Penteado, R.; Daemme, L.C.; Gatti, L.V.; Alvim, D.S. Measurements of Emissions from Motorcycles and Modeling Its Impact on Air Quality. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2013, 24, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.C.; Chang, P.K.; Hung, P.C.; Chou, C.C.K.; Chi, K.H.; Hsiao, T.C. Characterizing Emission Factors and Oxidative Potential of Motorcycle Emissions in a Real-World Tunnel Environment. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team BikeAdvice. Types of Motorcycle Emissions and Their Effects. Available online: https://bikeadvice.in/types-emissions-effects/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Redman, C. The Impact of Motorcycles on Air Quality and Climate Change: A Study on the Potential of Two-Wheeled Electric Vehicles. Bachelor’s Thesis, Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.A.; Kumar, P.; Alonso, M.F.; Andreão, W.L.; Pedruzzi, R.; dos Santos, F.S.; Moreira, D.M.; Albuquerque, T.T.d.A. Traffic Data in Air Quality Modeling: A Review of Key Variables, Improvements in Results, Open Problems and Challenges in Current Research. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, S.; Ramadurai, G.; Shiva Nagendra, S.M. Real-World Emissions of Gaseous Pollutants from Motorcycles on Indian Urban Arterials. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2019, 76, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.C.; Chen, T.C. Direct and Indirect Factors Affecting Emissions of Cars and Motorcycles in Taiwan. Transportmetrica 2010, 6, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduwayezu, G.; Zhao, P.; Pilesjö, P.; Bizimana, J.P.; Mansourian, A. Multilevel Small-Area Childhood Stunting Risk Estimation: Insights from Spatial Ensemble Learning, Agro-Ecological and Environmentally Remotely Sensed Indicators. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angier, D.M.; Mayer, J.D. A Comparison of Methods for Binning Responses to Open-Ended Survey Items About Everyday Events: A New Tailored-Binning Approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2025, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrettini, M.; Hennig, C.M.; Viroli, C. The Quantile-Based Classifier with Variable-Wise Parameters. Can. J. Stat. 2025, 53, e11837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulle, M. Optimal Bin Number for Equal Frequency Discretizations in Supervized Learning. Intell. Data Anal. 2005, 9, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, B.F.J.; Navarro Alberto, J.A.; Gerow, K. Multivariate Statistical Methods: A Primer. In Multivariate Statistical Methods; McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González-Estrada, E.; Villaseñor, J.A.; Acosta-Pech, R. Shapiro-Wilk Test for Multivariate Skew-Normality. Comput. Stat. 2022, 37, 1985–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasenor Alva, J.A.; Estrada, E.G. A Generalization of Shapiro–Wilk’s Test for Multivariate Normality. Commun. Stat. Methods 2009, 38, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarland, T.W.; Yates, J.M. Introduction to Nonparametric Statistics for the Biological Sciences Using R; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, F.; Correia, A.; Silva, E.C.E. Air Quality Assessment in Portugal and the Special Case of the Tâmega e Sousa Region. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, Rome, Italy, 27–29 January 2017; p. 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yun, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, X.; Yue, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Vehicle Emissions in a Megacity of Xi’an in China: A Comprehensive Inventory, Air Quality Impact, and Policy Recommendation. Urban Clim. 2023, 52, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, N.B.; Yang, H.H.; Wang, L.C.; Hsu, Y.T.; Zhang, H.Y.; Young, L.H.; Lu, J.H. VOCs Emission Characteristics in Motorcycle Exhaust with Different Emission Control Devices. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.L.T.; Nguyen Duc, K.; Le, A.T.; Nghiem, T.D.; Than, H.Y.T. Impact of Real-World Driving Characteristics on the Actual Fuel Consumption of Motorcycles and Implications for Traffic-Related Air Pollution Control in Vietnam. Fuel 2023, 345, 128256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Multivariate Data Analysis for Outcome Studies. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, A.M. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S. Multivariate Linear Regression. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Man, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, W.; Huang, C.; Jing, S.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chen, D.; He, K.; et al. VOC and IVOC Emission Features and Inventory of Motorcycles in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.H.; Chiang, H.L.; Hsu, Y.C.; Peng, B.J.; Hung, R.F. Development of a Local Real World Driving Cycle for Motorcycles for Emission Factor Measurements. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 6631–6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, A.M.; Gunarta, S. Model of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emission from Motorcycle to the Manufactures, Engine Displacement, Service Life and Travel Speed. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 776, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurl, S.; Keller, S.; Lankau, M.; Hafenmayer, C.; Schmidt, S.; Kirchberger, R. RDE Methodology Development for Motorcycle Emissions Assessment. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2025, 7, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjawane, L.E. A Systematic Literature Review: Traffic Management for Motorcycles to Improve Urban Road Air Quality. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2026, 54, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.T.; Muttamara, S.; Laortanakul, P. Evaluation of Air Pollution Burden from Contribution of Motorcycle Emission in Bangkok. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2001, 131, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.S. Urban Transportation Mode Choice and Carbon Emissions in Southeast Asia. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Pathak, S.; Sood, V.; Singh, Y.; Channiwala, S.A. Real World Vehicle Emissions: Their Correlation with Driving Parameters. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2016, 44, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, P.; Sahu, R.; Elumalai, S.P. Development of Emission Factors for Motorcycles and Shared Auto-Rickshaws Using Real-World Driving Cycle for a Typical Indian City. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Khader, A.I.; Martin, R.S. On-the-Road Testing of the Effects of Driver’s Experience, Gender, Speed, and Road Grade on Car Emissions. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, H.; French, B. A Monte Carlo Comparison of Robust MANOVA Test Statistics. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2013, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmamaw, M.; Tiku Mereta, S.; Ambelu, A. Response of Macroinvertebrates to Changes in Stream Flow and Habitat Conditions in Dinki Watershed, Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L.; Ullman, J. Using Multivariate Statistics; Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-13-479054-1. [Google Scholar]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Modeling with Crossed Random Effects for Subjects and Items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, L.K.; Devkota, N.; Dhakal, K.; Poudyal, R.; Mahato, S.; Paudel, U.R.; Parajuli, S. Consumer’s Behavioural Intention towards Adoption of e-Bike in Kathmandu Valley: Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 16237–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.; Macedo, E.; Fernandes, P.; Coelho, M.C. A Combined Framework of Biplots and Machine Learning for Real-World Driving Volatility and Emissions Data Interpretation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.H.; Heald, C.L.; Cappa, C.D.; Farmer, D.K.; Fry, J.L.; Murphy, J.G.; Steiner, A.L. The Complex Chemical Effects of COVID-19 Shutdowns on Air Quality. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklanov, A.; Zhang, Y. Advances in Air Quality Modeling and Forecasting. Glob. Transit. 2020, 2, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, R.; Kingston, P.; Neale, D.W.; Brown, M.K.; Verran, B.; Nolan, T. Monitoring On-Road Air Quality and Measuring Vehicle Emissions with Remote Sensing in an Urban Area. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 218, 116978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | How to Measure It | Influence on Emissions |

|---|---|---|

| Target variables | ||

| Emission pollutants CO2, CO, NO2, and HC | Target variables direct measurements of emissions measured in % for CO2, and in Parts Per Million (ppm) for, NO2, HC, CO | |

| Predictors | ||

| 1. Motorcycle characteristics | ||

| Year of manufacture | can be treated as a ratio if converted to vehicle age | Older motorcycles emit more due to engine wear and outdated emission control technology, increasing CO and NO2 [36]. |

| Engine capacity (cc) | ratio | Higher capacity correlates with greater fuel combustion, elevating CO2 and NO2 [37]. |

| Fuel type | e.g., petrol, diesel | Gasoline emits more CO and HC, which increases pollutants [36]. |

| Engine condition | e.g., good, noisy, and vibrating | Worn-out engines increase emissions due to incomplete combustion, leading to higher HC, CO, and smoke [37]. |

| Maintenance frequency | e.g., weekly, monthly, and rarely | Poor maintenance results in inefficient combustion and higher emissions [38]. |

| 2. Driver behavior and usage | ||

| Driving experience | years | Experienced drivers may operate more efficiently, reducing harsh acceleration that increases emissions. Inexperienced drivers accelerate/brake aggressively, raising HC and CO [39]. |

| Traffic rule adherence | on a scale (e.g., always, sometimes, and never) | Non-compliance often leads to aggressive driving (e.g., rapid starts), raising emissions [40]. |

| Average fuel consumption (l/km) | continuous | Higher consumption (l/km) directly increases CO2 and black carbon (BC) emissions [41]. |

| Daily mileage/driving distance | continuous | Longer distances increase total emissions, although per-km efficiency might stay constant. |

| Fuel purchase frequency | times/day | Frequent purchases may reflect inefficient fuel use or long daily operation hours, leading to higher cumulative emissions [36]. |

| 3. Socioeconomic/operational context | ||

| Average number of passengers/days | continuous | Higher loads can increase fuel consumption and stress the engine, slightly raising emissions [38]. |

| Maintenance cost/month | continuous | Low spending might reflect poor maintenance and increasing emissions. High cost could indicate frequent repairs due to inefficiencies [42]. |

| Driver age | age | Younger or older drivers may have different driving habits, which influence emissions [38]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abaho, G.G.; Munyazikwiye, B.B.; Bizimana, H.; Nikuze, J.; Ndekezi, M.; Mutabaruka, J.d.D.; Kabanda, D.R.; Mutuyeyezu, M.; Habiyakare, T.; Tuyizere, E.; et al. Understanding Motorcycle Emissions Across Their Technical, Behavioral, and Socioeconomic Determinants in the City of Kigali: A Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010047

Abaho GG, Munyazikwiye BB, Bizimana H, Nikuze J, Ndekezi M, Mutabaruka JdD, Kabanda DR, Mutuyeyezu M, Habiyakare T, Tuyizere E, et al. Understanding Motorcycle Emissions Across Their Technical, Behavioral, and Socioeconomic Determinants in the City of Kigali: A Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbaho, Gershome G., Bernard B. Munyazikwiye, Hussein Bizimana, Jacqueline Nikuze, Moise Ndekezi, Jean de Dieu Mutabaruka, Donald Rukotana Kabanda, Maximillien Mutuyeyezu, Telesphore Habiyakare, Emmanuel Tuyizere, and et al. 2026. "Understanding Motorcycle Emissions Across Their Technical, Behavioral, and Socioeconomic Determinants in the City of Kigali: A Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010047

APA StyleAbaho, G. G., Munyazikwiye, B. B., Bizimana, H., Nikuze, J., Ndekezi, M., Mutabaruka, J. d. D., Kabanda, D. R., Mutuyeyezu, M., Habiyakare, T., Tuyizere, E., Matabaro, T., Bimenyimana, P. B., & Nduwayezu, G. (2026). Understanding Motorcycle Emissions Across Their Technical, Behavioral, and Socioeconomic Determinants in the City of Kigali: A Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis. Atmosphere, 17(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010047