Ice Accretion Forecast for Power Grids Based on Pangu Model and Machine Learning Correction: A Case Study on Late December 2021 in Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Spatiotemporal Evolution and Meteorological Conditions of the Ice Accretion Process

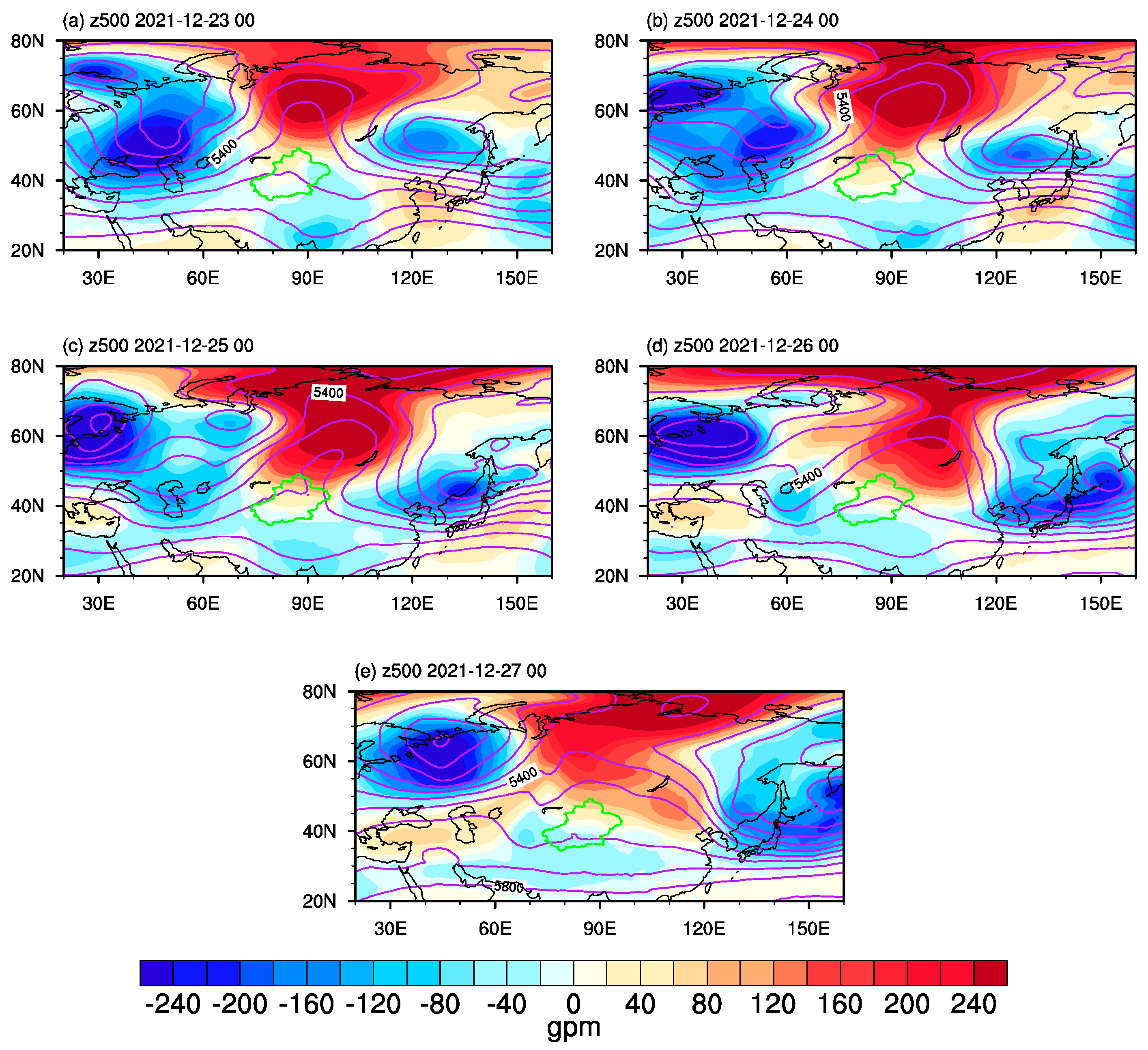

3.2. Large-Scale Atmospheric Circulation and Physical Causes for the Ice Accretion Process

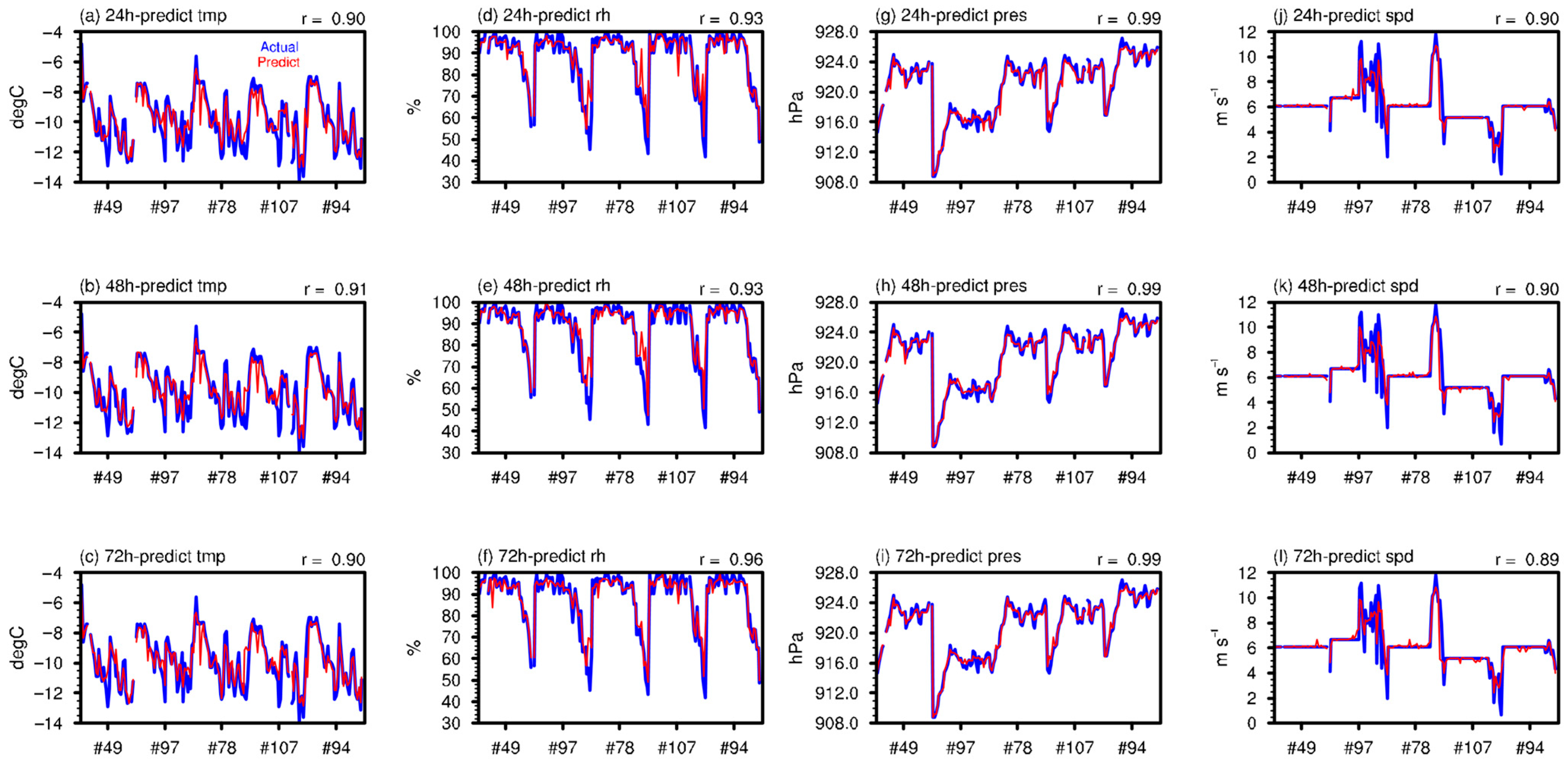

3.3. A Preliminary Study on Ice Accretion Prediction Based on the Pangu Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schweikert, A.E.; Deinert, M.R. Vulnerability and resilience of power systems infrastructure to natural hazards and climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 2021, 12, e724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, J.; Fernández-Pérez, A.; Mühlhofer, E.; Nirandjan, S.; Borgomeo, E.; Becher, O.; Voskaki, A.; Oughton, E.J.; Stankovski, A.; Greco, S.F.; et al. Quantifying climate risks to infrastructure systems: A comparative review of developments across infrastructure sectors. PLoS Clim. 2024, 3, e0000331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X. Progress in research on ice accretions on overhead transmission lines and its influence on mechanical and insulating performance. Front. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2012, 7, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretterklieber, T.; Neumayer, M.; Flatscher, M.; Becke, A.; Brasseur, G. Model based monitoring of ice accretion on overhead power lines. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference Proceedings, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–26 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, P.; Havard, D.; Laneville, A. Effect of Ice and Snow on the Dynamics of~Transmission Line Conductors. In Atmospheric Icing of Power Networks; Farzaneh, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Nie, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Preventing Ice Accretion: Design Strategies for Anti-Icing Surfaces. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 36082–36105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Bie, Z.; Wang, X. Characteristics Analysis and Risk Modeling of Ice Flashover Fault in Power Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. Inter-Provincial Power Transmission and Its Embodied Carbon Flow in China: Uneven Green Energy Transition Road to East and West. Energies 2021, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, X.; Liu, W.; Yue, Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Lei, Z. Fault analysis and comprehensive improvement of Xinjiang power grid transmission lines easy to ice. IET Conf. Proc. 2022, 2021, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y. Research on Ice Accumulation of Transmission Lines in Xinjiang. In Proceedings of the 2022 Power System and Green Energy Conference (PSGEC), Shanghai, China, 25–27 August 2022; pp. 1012–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Q.; Gong, B.; Gu, T.; Liao, Y.; Ye, H.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, H. Synoptic Characteristics of a Continuous Ice Covering Event on Ultra-High Voltage Transmission Lines in 2023. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Energy Engineering and Power Systems (EEPS), Hangzhou, China, 9–11 August 2024; pp. 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, M. Analysis of Icing and Ice Shedding Failures on 750 kV Transmission Lines in Xinjiang. Zhejiang Electr. Power 2020, 39, 58–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wan, R.; Sun, J.; Gao, Z.; Yang, J. Influence of key parameters of ice accretion model under coexisting rain and fog weather. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1036692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Feng, T.; Xu, X.; Hu, Z.; Cao, X.; Peng, J. Extended-range Forecasts of Power Grid Ice Accretion in Southern China: Case Studies. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 3rd Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Changsha, China, 8–10 November 2019; pp. 2443–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Virk, M.S.; Jiang, X. Study of Wind Flow Angle and Velocity on Ice Accretion of Transmission Line Composite Insulators. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 151898–151907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musilek, P.; Arnold, D.; Lozowski, E.P. An Ice Accretion Forecasting System (IAFS) for Power Transmission Lines Using Numerical Weather Prediction. SOLA 2009, 5, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosek, J.; Musilek, P.; Lozowski, E.; Pytlak, P. Forecasting severe ice storms using numerical weather prediction: The March 2010 Newfoundland event. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGaetano, A.T.; Belcher, B.N.; Spier, P.L. Short-Term Ice Accretion Forecasts for Electric Utilities Using the Weather Research and Forecasting Model and a Modified Precipitation-Type Algorithm. Weather Forecast. 2008, 23, 838–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, H. FuXi: A cascade machine learning forecasting system for 15-day global weather forecast. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Xie, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Gu, X.; Tian, Q. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 2023, 619, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, S.; Alexe, M.; Chantry, M.; Dramsch, J.; Pinault, F.; Raoult, B.; Bouallègue, Z.B.; Clare, M.; Lessig, C.; Magnusson, L. AIFS: A New Ecmwf Forecasting System. ECMWF Newsletter. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/newsletter/178/news/aifs-new-ecmwf-forecasting-system (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Sun, J.; Cao, Z.; Li, H.; Qian, S.; Xin, W.; Limin, Y.; Wei, X. Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology to Numerical Weather Prediction. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Zhu, X.; Yun, T.; Hao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qin, Y. Applicability Assessment of the Pangu Weather Forecast Model in Northeast China. Desert Oasis Meteorol. 2025, 19, 157–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Earth Science. How do I Convert Specific Humidity to Relative Humidity? 2016. Available online: https://earthscience.stackexchange.com/questions/2360/how-do-i-convert-specific-humidity-to-relative-humidity (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. New Machine Learning Algorithm: Random Forest. In Information Computing and Applications. ICICA. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Liu, B., Ma, M., Chang, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 54, 1937–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulud, D.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A Review on Linear Regression Comprehensive in Machine Learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, M.P. An Efficient Ridge Regression Algorithm with Parameter Estimation for Data Analysis in Machine Learning. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Khanna, R. Support Vector Regression. In Efficient Learning Machines; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.; Tsai, S.J. Machine Learning in Neural Networks. In Frontiers in Psychiatry. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Kim, Y.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

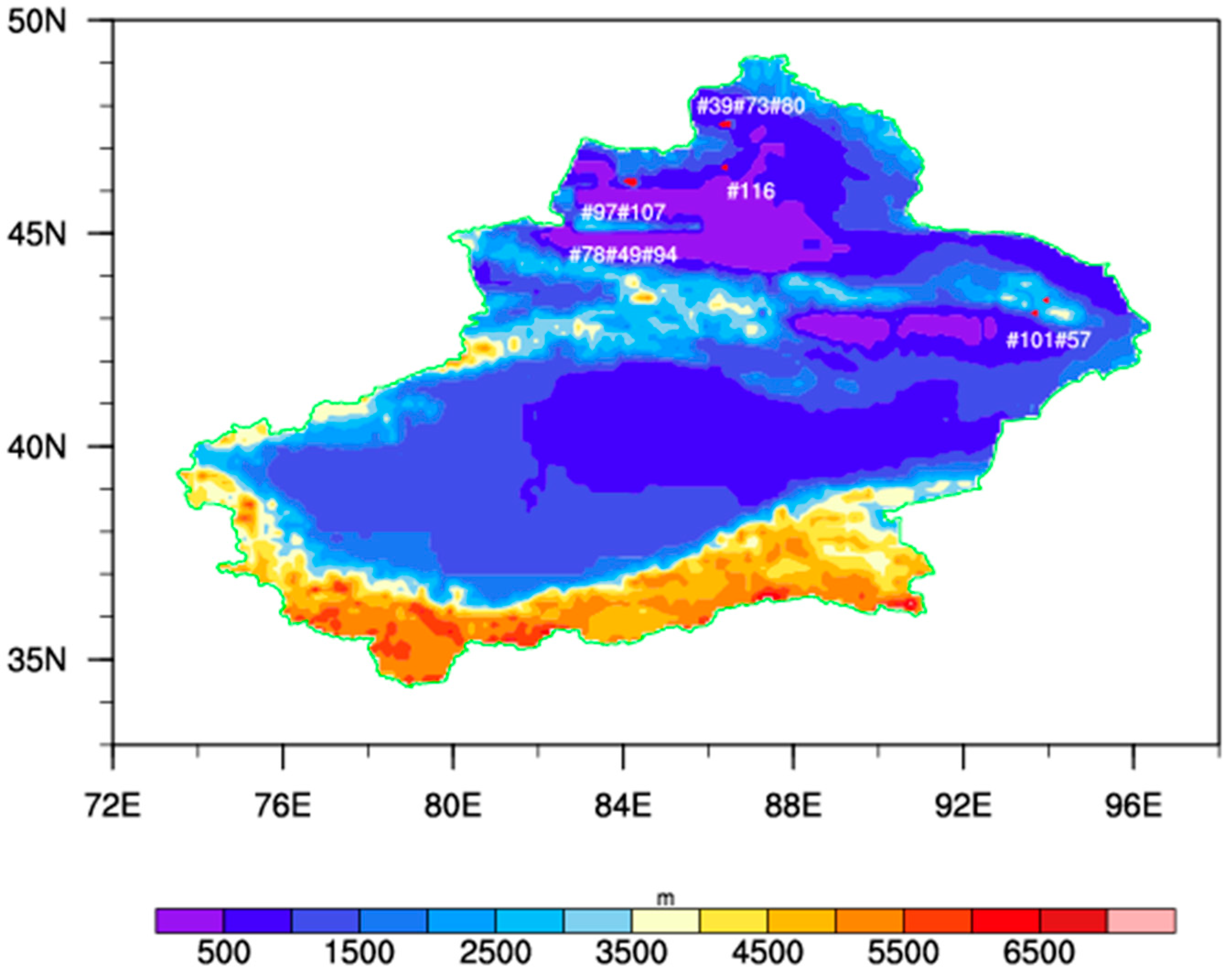

| Name | ID | Lon | Lat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ane | #49 | 84.08° E | 46.23° N |

| Fengsha | #116 | 86.38° E | 46.55° N |

| Hailong | #39 | 86.33° E | 47.56° N |

| Hailong | #73 | 86.43° E | 47.56° N |

| Hailong | #80 | 86.45° E | 47.57° N |

| Hashan | #57 | 93.66° E | 43.13° N |

| Mayou | #101 | 93.93° E | 43.43° N |

| Tiedong | #97 | 84.19° E | 46.17° N |

| Tiee | #78 | 84.24° E | 46.20° N |

| Tierun | #107 | 84.17° E | 46.22° N |

| Tieyi | #94 | 84.20° E | 46.22° N |

| 24 h Predicted Temperature | MSE | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 2.36 | 1.28 | 0.13 |

| Gradient Boosting | 2.33 | 1.22 | 0.14 |

| Linear Regression | 3.16 | 1.47 | −0.17 |

| Ridge Regression | 3.27 | 1.57 | −0.21 |

| SVR | 3.40 | 1.51 | −0.26 |

| Neural Network | 3.65 | 1.51 | −0.35 |

| 24 h predicted wind speed | MSE | MAE | R2 |

| Random Forest | 1.66 | 0.61 | 0.48 |

| Gradient Boosting | 1.79 | 0.70 | 0.43 |

| Linear Regression | 2.88 | 1.20 | 0.09 |

| Ridge Regression | 2.85 | 1.18 | 0.10 |

| SVR | 2.97 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Neural Network | 2.14 | 1.07 | 0.32 |

| Variables | 24 h Prediction | 48 h Prediction | 72 h Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting |

| Relative humidity | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting |

| Pressure | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting | Gradient Boosting |

| Wind speed | Random Forest | Random Forest | Random Forest |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, M.; Yang, X. Ice Accretion Forecast for Power Grids Based on Pangu Model and Machine Learning Correction: A Case Study on Late December 2021 in Xinjiang, China. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010023

Li Y, Yang Y, Li M, Zhao M, Yang X. Ice Accretion Forecast for Power Grids Based on Pangu Model and Machine Learning Correction: A Case Study on Late December 2021 in Xinjiang, China. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yujie, Yang Yang, Meng Li, Mingguan Zhao, and Xiaojing Yang. 2026. "Ice Accretion Forecast for Power Grids Based on Pangu Model and Machine Learning Correction: A Case Study on Late December 2021 in Xinjiang, China" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010023

APA StyleLi, Y., Yang, Y., Li, M., Zhao, M., & Yang, X. (2026). Ice Accretion Forecast for Power Grids Based on Pangu Model and Machine Learning Correction: A Case Study on Late December 2021 in Xinjiang, China. Atmosphere, 17(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010023