1. Introduction

Quantifying the likelihood of direct lightning attachment to structures, including both downward and upward discharges, is central to lightning-risk assessment and protection design [

1]. For structures on flat terrain, exposure depends mainly on their dimensions and the local thunderstorm activity [

1]. When towers are located on mountaintops or other elevated terrain, however, their lightning incidence is strongly affected by the enhanced ambient electric field produced by topography [

2,

3]. Accurate estimation of this enhancement—and of the corresponding effective height, defined as the equivalent flat-ground height yielding the same lightning exposure—is essential for reliable exposure assessment, for calibrating measurements at instrumented sites, and for comparison with established protection guidelines [

4,

5]. Recent comprehensive reviews of lightning striking characteristics to tall structures [

6,

7] have further clarified the physical conditions leading to self-initiated and nearby-triggered upward flashes. Self-initiated upward flashes develop when the ambient quasi-static field becomes sufficiently enhanced to launch an upward leader, whereas nearby-triggered flashes occur when a downward lightning discharge in the vicinity produces a rapid field change that initiates the upward leader [

6]. Recent field observations at tall structures further reinforce the prevalence and characteristics of these initiation mechanisms [

8].

The effective height concept has long been used to characterize the increased likelihood of lightning attachment to elevated structures, with early empirical studies seeking to relate it to observed lightning exposure. Pierce [

2] inferred effective heights from lightning frequency data, while Eriksson [

3,

9] established the empirical relationship between tower height and the proportion of upward flashes. Based on aggregated lightning statistics for high structures and power lines, Eriksson [

9] expressed the percentage of upward flashes,

Pu, as a function of structure height

h (m):

This relation, originally introduced to model lightning incidence to power lines, became a standard empirical relation for evaluating the likelihood of upward-flash initiation and was later adopted by Shindo [

5] in validating his electrostatic formulation for mountaintop towers.

A significant advancement toward a physically based description was achieved by Rizk [

10,

11], who formulated analytical conditions for leader inception and propagation from grounded conductors exposed to ambient thundercloud fields. Building upon that work, Zhou et al. [

4] derived an analytical expression for the effective height of mountaintop towers by combining Rizk’s inception criterion with geometric scaling of the mountain profile. Their formulation reproduced observed effective heights at several instrumented sites—such as Gaisberg, San Salvatore, and Peissenberg—demonstrating that the analytical approach captured the essential discharge physics under quasi-static thundercloud fields.

As a simplified alternative, Shindo [

5] proposed a tip-field equivalence method, in which the electric field at the tip of a mountaintop tower is equated to that of a taller structure on flat ground. This electrostatic approach reproduced observed trends when combined with Eriksson’s empirical relation for P

u but did not explicitly model leader inception or space-charge development. Its results therefore depended strongly on assumed geometric and field parameters such as tower radius and cloud-charge height.

Despite the insights provided by these analytical and empirical formulations, their applicability to complex terrain remains limited by geometric idealizations and the absence of explicit leader physics. In particular, the coupling between terrain curvature, tower geometry, and the stabilization field required for self-initiated upward-leader development has not been resolved within a unified framework.

The present study addresses this gap by implementing a two-step numerical framework that combines finite-element electrostatic field calculations with a leader-inception and propagation model. The method explicitly determines the stabilization field required for self-sustained upward leader development from a mountaintop tower and derives the corresponding effective height. This framework is applied to well-known instrumented towers in lightning research, with site configurations represented by a truncated-cone tower geometry featuring a hemispherical tip situated on a hemispherical mountain to approximate their electrostatic behavior. The simulated results are systematically compared with the analytical formulation of Zhou et al. [

4], the electrostatic model of Shindo [

5], and the empirical relation of Eriksson [

9] to evaluate consistency, limitations, and physical implications for self-initiated upward flashes.

2. Methodology

To estimate the effective height of mountaintop towers subject to self-initiated upward lightning flashes, a simulation-based leader inception and propagation model was implemented. The model resolves the inception of streamers at the tower tip, their transition into a self-sustained leader, and the subsequent leader–streamer propagation towards the thundercloud. The electrostatic fields are computed numerically using the finite-element method (FEM), allowing systematic analysis of representative tower–terrain configurations that capture the essential field enhancement characteristics. The minimum ambient electric field sustaining continuous upward leader development defines the stabilization field of the structure, from which its effective height is determined.

To represent the inception and propagation processes accurately, the modeling framework adopted in this study builds on established physical and numerical formulations describing long-gap discharges and lightning-leader development [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. These include the discharge sequence and long-spark mechanism described by Gallimberti and collaborators [

12,

14,

15,

16]; the analytical models developed by Rizk to describe leader inception, propagation, and breakdown in long air gaps [

13] and their subsequent extension to lightning incidence on tall structures [

10,

11]; and the self-consistent physical formulations proposed by Becerra and Cooray for upward-leader initiation and propagation [

17,

18], previously employed in upward-flash studies of tall structures such as wind turbines [

19].

The inception of upward flashes follows the same fundamental sequence of discharge processes: electron avalanches initiated at the tower tip evolve into streamers, which then undergo streamer-to-leader transition, followed by leader propagation sustained by the local electric field [

10,

19,

20]. The modeling framework adopted here explicitly incorporates these stages, providing a consistent basis for evaluating inception and propagation conditions of towers exposed to quasi-static thundercloud fields.

Tall masts and towers on mountaintops are especially prone to this process, since the quasi-uniform background field produced by the charging of the thundercloud is strongly enhanced at their tips [

4,

5,

10]. This enhancement lowers the inception threshold for upward leaders, making exposed mountaintop structures particularly susceptible to initiating flashes, as supported by field observations of upward flashes from instrumented towers [

3,

6,

7,

8,

21]

The present work follows these principles by implementing the leader-inception and propagation framework in a simulation-based model. Electrostatic fields are resolved with the finite-element method, while inception and propagation conditions are evaluated iteratively, as detailed in the following subsections.

2.1. Streamer Inception Criterion

Electron avalanches developing in the high-field region near the tower tip are evaluated using Gallimberti’s inception criterion [

12,

16]. The number of charged particles is expressed as the integral of the net ionization rate over the active region where the ionization coefficient (

⍺) exceeds the attachment coefficient (

η).

In the model, the prospective series of electron avalanches growing in the vicinity of the tower tip are represented by a single equivalent avalanche. The number of charged particles contained in the equivalent avalanche head,

Ne, is determined by the integrating of the rate equation for collisional ionization [

12,

16]:

where

d is the extent of the active region. The threshold condition for initiating a self-sustained streamer is

Ne ≥

Nc ≈ 10

8–10

9. Here,

Nc denotes the critical electron number for avalanche-to-streamer transition. The inception criterion is applied under the standard assumption that natural background ionization supplies at least one free electron in the high-field region to initiate avalanche growth.

The coefficients

α and

η are determined from the transport functions proposed by Morrow and Lowke [

22], expressed in terms of the reduced field

E/

N. In this context,

N denotes the neutral particle density (cm

−3).

To account for the variation in air density with altitude, the density

N is corrected using an exponential dependence [

23],

where

z is the altitude of the evaluation region and

λd = 7.64 × 10

3 m is the characteristic density scale height. This correction ensures that the reduced field

E/

N and the corresponding ionization coefficients

α and

η properly reflect the lower air density at mountaintop elevations.

2.2. Streamer-to-Leader Transition Mechanism

The transition from a stable streamer to a leader is evaluated using the distance–voltage (

U–

ℓ) diagram method [

15,

16,

17,

20], which provides the foundation for the iterative framework applied to model the leader propagation (

Figure 1). The figure shows the background potential curve

Ub(

ℓ) and the

Ust(

ℓ) =

Est•

ℓ line, representing the nearly constant electric field sustained in the corona region during streamer propagation (typically about 4.5–5.0 × 10

5 V/m for positive discharges [

16,

20]). The intersection between these two curves determines the extent of the streamer region and the amount of accumulated space charge available for leader inception in each case.

The accumulated space charge generated in the corona region is proportional to the area enclosed by

Ub and

Ust:

where ℓ is the axial coordinate,

ℓS is the axial extent, and

kq is the geometrical factor. In this study,

kq = 3.2 × 10

−11 C/V, corresponding to a conical streamer region in an axisymmetric configuration [

17].

The streamer-to-leader transition is assumed to occur when

q exceeds the critical threshold

qc ≈ 1 µC, corresponding to the thermalization of the streamer stem [

14,

16]. At this point, heating and ion detachment increase the local conductivity, producing a conductive leader channel that serves as the initial condition for the propagation model presented in

Section 2.3.

2.3. Leader Propagation Model

Following the streamer-to-leader transition described in

Section 2.2, the subsequent leader development is simulated through successive iterations of the distance–voltage framework. Each iteration represents one advancement of the leader tip, with the associated corona charge and extent recalculated. Superscripts (

i) and (

i − 1) denote the current and previous iteration, respectively;

ℓL(i) and

ℓS(i) are the leader length and streamer extent at iteration

i, and

UT(i)(

ℓ) is the corresponding total axial potential.

Figure 1 schematically represents this iterative process, showing the background potential, the corona field line at leader inception, and the successive total potentials in each propagation step.

Leader-channel drop. In each iteration, the voltage drop along the leader channel is evaluated with Rizk’s formulation [

13]:

where

ℓL is the leader length,

Ei,

E∞ are the initial and final leader gradients, and

x0 =

vℓ•

τ is the leader space constant defined by the leader velocity

vℓ and time constant

τ. All leader-channel parameters (

Ei,

E∞,

vℓ,

τ) were adopted consistently with the values employed by Rizk for tall-structure applications [

10,

11].

Piecewise total potential. The total potential along the axis is then assembled from three regions—leader, corona, and background as:

UT(i)(ℓ) = UL(ℓ), for 0 ≤ ℓ ≤ ℓL(i);

UT(i)(ℓ) = UL(ℓL(i)) + Est(ℓ − ℓL(i)), for ℓL(i) < ℓ ≤ ℓS(i);

UT(i)(ℓ) = Ub(ℓ), for ℓ ≥ ℓS(i).

The streamer extent ℓS(i) is obtained from the intersection condition: UL(ℓL(i)) + Est(ℓ − ℓL(i)) = Ub(ℓS(i)).

Incremental charge and advancement. The incremental charge added in iteration

i is proportional to the enclosed area between successive total potentials, as illustrated in

Figure 1:

and the leader tip advances by an increment proportional to the available charge whenever this exceeds a sustaining threshold; otherwise, the leader is assumed to extinguish:

where

qℓ is the charge per unit length required to convert the streamer stem into a new leader segment. A value of

qℓ = 65 × 10

−5 C/m was adopted, consistent with values reported for long-gap discharges [

16] and applied in upward-leader simulations and applied in upward-leader simulations [

17].

Iterations continue until the simulated leader either extinguishes or reaches the prescribed cloud-base height H (1.2 km or 1.5 km for very tall configurations), at which point an upward flash is assumed to occur.

2.4. Numerical Framework Implementation

Electrostatic field and potential distributions were computed using a three-dimensional finite-element model in COMSOL Multiphysics’ AC/DC module. Towers were represented as truncated-cone conductors terminated by hemispherical tips, and mountaintops as hemispherical surfaces. All conducting bodies were grounded and treated as perfect conductors. A uniform reference background field of 1 kV/m was applied to reproduce the quasi-static thundercloud field, consistent with the linearity of the governing electrostatic equations.

The computational domain was implemented as a cylindrical geometry with an outer infinite element layer to approximate an unbounded region. This configuration followed recommended practices regarding geometry definition and meshing strategies to ensure numerical stability and accuracy [

24]. Mesh refinement was applied to ensure accurate resolution of electric field gradients in regions exhibiting steep variations.

Electrostatic field solutions obtained from the FEM solver were integrated with the leader-inception and propagation framework, implemented in MATLAB, and subsequently applied in the effective-height procedure (

Section 2.5). MATLAB served as the primary environment for executing the physical models and coordinating iterative FEM computations through bidirectional coupling with COMSOL. This integration enabled systematic evaluation of leader inception and propagation across different tower-terrain configurations while maintaining physical consistency and computational efficiency.

2.5. Effective-Height Derivation

The effective height of a mountaintop tower was determined through a two-step coupled COMSOL–MATLAB procedure that compares the stabilization field of the mountaintop configuration with that of an equivalent flat-ground tower. Both steps employed the coupled framework introduced in

Section 2.4 and the physical criteria defined in

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3.

A tower of nominal height h mounted on a grounded hemispherical mountain of radius a was analyzed to determine the stabilization field (Estab). A FEM solution was obtained for E = 1 kV/m, and subsequent field values were generated by linear scaling in MATLAB. The background-field magnitude was varied using the bisection method. For each trial field, the leader-progression algorithm evaluated inception, streamer-to-leader transition, and propagation.

The minimum field that produced continuous propagation to the cloud base defined

Estab. This definition represents a broader interpretation of the stabilization-field concept than the short-segment criteria adopted by Lalande [

20] and Becerra and Cooray [

17] for upward-connecting leaders, adapting it to self-initiated upward flashes.

- 2.

Flat-ground configuration.

To determine the equivalent flat-ground configuration, a subsequent simulation series is performed using a tower model on level terrain. The background field is fixed to Estab from step 1, and the tower height hflat was varied iteratively using the bisection method. At each iteration, COMSOL recalculated the electrostatic distribution, and MATLAB applied the same discharge-evaluation criteria.

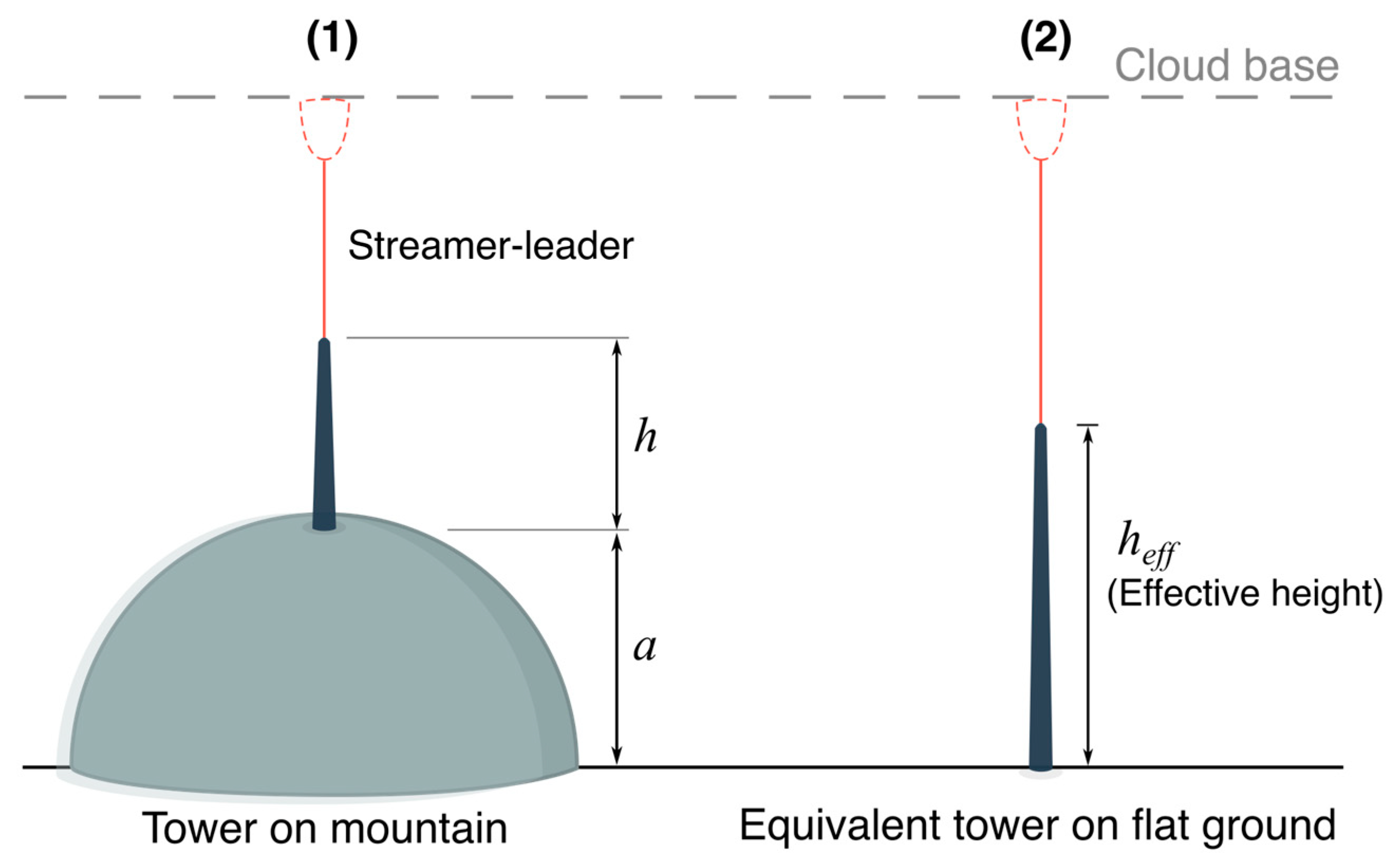

The smallest flat-ground tower height satisfying the propagation condition to produce an upward flash is identified and defined as the effective height

heff (see

Figure 2). By construction,

heff represents the height of a flat-ground tower that requires the same background field as the mountaintop tower for a self-initiated upward flash. This two–step approach incorporates terrain-induced field enhancement into a single equivalent parameter, enabling direct correspondence between mountaintop and flat-ground towers.

- 3.

Tower Geometry and Parametrization

Each tower was represented as a truncated-cone conductor terminated by a hemispherical tip, with reference dimensions rbase = 0.08h and rtop = 0.10rbase. To evaluate the influence of tower geometry, five configurations were generated for each tower:

Base-radius sweep: rbase = 0.06h and 0.10h, with proportional scaling of the top radius (rtop = 0.10rbase);

Top-radius sweep: rtop = 0.08rbase and 0.12rbase, with rbase = 0.08h held constant.

This combined set therefore yielded five distinct geometries per tower: one base configuration and four sensitivity variations. The mountain geometry remained constant to isolate tower effects and the resulting range of

heff values—expressed as the base-case result ±

Δheff defines the robustness envelope used in the results analysis (

Section 3).

3. Results

The simulations produced, for each tower–terrain configuration, the corresponding stabilization field

Estab—previously defined as the minimum background field enabling continuous leader propagation to the cloud base—and the associated effective height

heff.

Table 1 lists the base-geometry values of both quantities together with robustness intervals (±

ΔEstab, ±

Δheff) derived from the geometry-sensitivity sweeps. The variations are modest—typically below 3% for

heff (corresponding to absolute deviations of about 0.5–5 m) and within 4–9 kV/m for

Estab—confirming the numerical stability of the model and showing that, within the tested truncated-cone geometries, the results depended only weakly on tower cross-section for realistic radius values representative of tall telecommunication towers. Across all sites,

Estab lies between 20 and 40 kV/m, decreasing systematically with increasing mountain radius—a trend that reflects the attenuation of terrain-induced field enhancement as the mountain becomes broader.

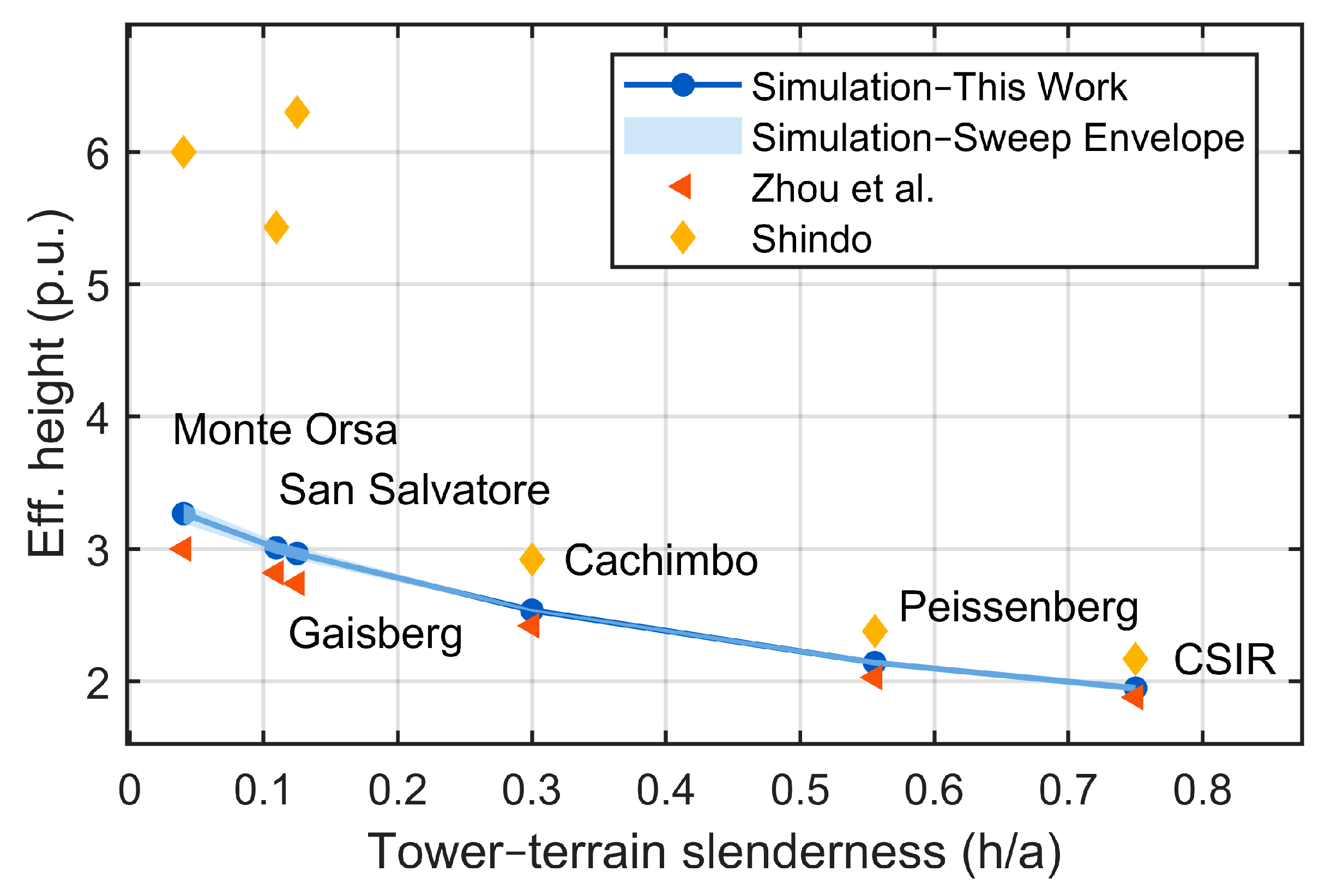

The stabilization fields and corresponding effective heights in

Table 1 reveal a coherent physical pattern: towers situated on broader mountains (small

h/

a) require lower ambient fields for self-initiated leader propagation and consequently exhibit larger effective heights, whereas towers on narrow or steep peaks (large

h/

a) demand higher stabilization fields and yield smaller

heff. To examine this dependence more quantitatively, the results were normalized by the actual tower height and expressed as the ratio

heff/

h plotted against the tower–terrain slenderness ratio

h/

a. This representation, shown in

Figure 3, enables direct comparison among towers of different dimensions and isolates the geometric influence of terrain on effective-height scaling.

To quantify this dependence, the normalized simulation results were fitted to a power-law relation of the form:

where C

1 and C

2 are regression coefficients obtained from least-squares fitting of the base-geometry cases in

Table 1. The resulting expression, valid for 0.04 <

h/

a < 0.75, is:

with a correlation coefficient R

2 = 0.94. This relation summarizes the normalized trend shown in

Figure 3 and provides a compact, physics-consistent representation of the simulation results. It enables direct estimation of the effective height of mountaintop towers from geometric parameters alone, complementing the detailed leader inception modeling.

To assess the agreement between the present framework and previous studies, the relative deviation in effective height was calculated as

where “ref” denotes the corresponding literature value. Positive deviations indicate that the present simulations yield higher effective heights. The results, arranged in order of decreasing tower–terrain slenderness, are summarized in

Table 2.

The deviations with respect to Zhou et al. [

4] remain within approximately 10% for all mountaintop cases (see

Table 2), exceeding the below-3% variability obtained from the geometry-sensitivity analyses but still well within the range expected for physical consistency. The close quantitative agreement confirms that the numerical framework developed in this work is physically consistent with Zhou’s analytical formulation while resolving the same representative tower–terrain configurations with greater physical and geometric detail. In comparison, Shindo’s simplified electrostatic approach [

5] yields systematically higher effective heights for broad mountains but differences of only about 10% for steeper or more isolated sites. The empirical formulations of Eriksson [

3] and Pierce [

2] show larger deviations, often exceeding 40–70%, reflecting their limited ability to represent detailed tower geometry and terrain curvature. Overall, the framework accurately resolves the geometric dependence of effective height, supporting the physical analyses presented in the following section. The implications of these results and the influence of model assumptions are examined in the following section.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Models

The present results confirm that the two-step numerical framework incorporating the leader inception and propagation model developed in this work reproduces the effective heights of mountaintop towers within about 10% of Zhou’s analytical formulation [

4]. This close correspondence demonstrates that both approaches capture the same underlying discharge physics. However, the present framework extends Zhou’s analytical formulation by systematically resolving the full electric-field and potential distributions throughout the tower–mountain domain and by explicitly simulating the upward leader development leading to flash initiation. This numerical formulation therefore provides a physically grounded extension of the Rizk-based model, applicable to more general geometries and field conditions. The agreement establishes a consistent physical foundation and provides a validated basis for examining how the tower-mountain geometry influences the stabilization field and effective height.

Shindo’s tip-field-equivalence method [

5] provides a simplified alternative to Zhou’s formulation, based purely on electrostatic field equivalence. It defines the effective height by equating the tip field of a mountaintop tower with that of a taller flat-ground structure and reproduces observed trends when combined with empirical upward-flash statistics. In the present comparison, Shindo’s method yields systematically higher effective height values than either Zhou’s formulation and the present simulations, particularly for towers on broad mountains such as Gaisberg and Monte Orsa. This overestimation likely results from the simplified treatment of charge redistribution along the mountain surface, which limits the model’s ability to moderate local field enhancement.

For Mt. San Salvatore, Shindo [

5] reported four effective height values—230 m, 250 m, 340 m, and 380 m—obtained for different assumed cloud-charge height (

Hc = 5 km and 1.5 km) and tower radii (

R = 1 and 5 m). The lower values (230 m and 250 m) correspond to the case with

Hc = 5 km, which represents the ambient thundercloud field, whereas the higher values (340 m and 380 m) were calculated after lowering

Hc to 1.5 km, effectively emulating an intensified background field acting on the tower. For each cloud-charge height, the larger tower radius (

R = 5 m) reduces the local curvature, thus requiring a stronger external field to produce the same tip enhancement as in the

R = 1 m cases; this results in higher field-equivalent heights. Shindo then adopted the configuration

Hc = 1.5 km and

R = 5 m, which yielded the largest effective height for Mt. San Salvatore (380 m), as the reference case based on a comparison with empirical observations. The same parameter set was subsequently applied to calculate the effective heights for the remaining mountaintop towers. However, the apparent agreement with field observations reported by Shindo may have been indirect, obtained by applying his calculated effective heights to Eriksson’s empirical relation for the percentage of upward flashes. Because that relation was derived from the same datasets used to infer empirical effective heights, the comparison might not constitute a fully independent validation. This adjustment may therefore represent a field-intensification proxy rather than the quasi-static conditions that lead to self-initiated upward flashes.

By contrast, the pioneering empirical relations proposed by Pierce [

2] and Eriksson [

3], though historically valuable, exhibit larger and more systematic deviations—often exceeding the simulated results by 50–100% (see

Table 2). Their reliance on long-term, site-specific lightning statistics limits their ability to generalize beyond the measurement conditions, particularly for complex or elevated terrain. As measurement instrumentation and high-speed observation techniques continue to improve, and as the initiation mechanisms of self-initiated and triggered upward flashes become better differentiated, empirical relations of this type are expected to evolve, potentially yielding revised coefficients or functional forms that reflect these advances. These differences emphasize the importance of coupling the effective-height concept with a physical model of leader inception and propagation rather than extrapolating from statistical correlations. Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed simulation framework reproduces the observed physical dependence on tower-to-mountain slenderness while providing improved consistency with the underlying discharge physics.

4.2. Physical Interpretation

The correlation derived in Equation (12) encapsulates this geometric dependence; as shown in

Figure 3, the normalized effective height (

heff/

h) decreases gradually with increasing tower-to-mountain slenderness (

h/

a). The modest exponent magnitude (−0.17) is consistent with electrostatic-similarity expectations and confirms that the geometric scaling of effective height is governed by broad, gradual trends rather than sharp terrain thresholds. This behavior reflects the competing effects of tower elevation and terrain curvature on the local electric-field enhancement: as the mountain becomes broader (small

h/

a), the combined structure behaves increasingly as a single elevated conductor, producing stronger field enhancement at the tower tip and being associated with lower stabilization fields for the initiation of self-sustained upward leaders. Conversely, narrow or steep peaks (large

h/

a) restrict the enhancement region, demanding higher background fields and leading to smaller normalized effective heights. This dependence was found to be weakly affected by tower cross-section, consistent with the robustness interval shown in

Figure 3, in the employed representative truncated-cone geometry, whose base and top radii were varied within realistic ranges representative of tall telecommunication towers.

4.3. Practical Implications

The physically based correlation presented herein as Equation (12), offers a rapid, geometry-driven tool for estimating the effective height of towers on mountaintops, provided that the site characteristics fall within the validated parameter range (0.04 < h/a < 0.75, truncated-cone tower geometry). This relationship can be directly applied in preliminary exposure assessments or design studies by substituting representative values of mountain radius (from topographic maps) and tower height. For installations situated on non-hemispherical or highly irregular terrain, or where additional accuracy is required, the full numerical approach detailed in this manuscript should be adopted.

4.4. Model Assumptions

To ensure computational feasibility and isolation of the dominant physical factors, this study employed well-defined simplifying assumptions regarding tower structure, terrain geometry, and discharge development. Towers were modeled as perfectly conducting, axisymmetric truncated cones with hemispherical tips, and placed atop idealized semi-spherical mountains. While enabling parametric variation in base and top radii and offering a more realistic tower representation than the slender rods or cylinders commonly used in analytical studies, this geometry does not capture the structural complexity of lattice frameworks or the true-to-form body dimensions of individual tower designs. The background electric field was treated as spatially uniform in the absence of the mountain and tower, and upward leader propagation was assumed vertical, non-branching and without tortuosity. These assumptions isolate the dominant electrostatic effects, establishing the framework’s scope as the evaluation of self-initiated upward discharges under quasi-static thundercloud fields.

4.5. Future Work

Extending the current framework to include more realistic and complex scenarios presents an important direction for future research. Potential extensions could incorporate irregular or multi-peak terrain alongside lattice-type tower structures to assess their influence on the effective height. This would improve predictions for commonly used infrastructure and enable more accurate site-specific risk assessments. Furthermore, future studies might employ numerical simulations or field measurements to investigate the impact of non-vertical leader trajectories on effective height.

Probabilistic coupling the present simulation framework with lightning-incidence models would enable estimation of total strike rates, bridging the gap between effective-height determination and practical lightning-performance evaluation for telecommunication towers in mountainous regions. Emphasizing the core topics outlined above will strengthen physical robustness and widen field applicability of effective height estimations in future studies.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that the tower-to-mountain ratio (h/a) governs the geometric scaling of the effective height, while tower cross-section contributes only marginally to the overall scaling. Within the representative truncated-cone configuration adopted in this study—featuring a hemispherical tip and base-to-top radius ratios representative of tall telecommunication towers—variations in tower radii altered the results by less than 3%, confirming the robustness of the model. These findings verify that the chosen geometry adequately represents tall telecommunication towers for effective-height estimation under self-initiated upward lightning conditions and provide quantitative evidence that mountain geometry, rather than tower detailing, dominates effective-height behavior. The physically grounded correlation for effective height (see Equation (12)), derived from this analysis and validated against existing models, offers a practical tool for rapid exposure assessment in preliminary design and site evaluation, applicable within the validated range for tower-mountain ratios (0.04 < h/a < 0.75). Collectively, these results strengthen the physical basis of the effective-height concept and demonstrate that a comprehensive, simulation-based framework can robustly capture terrain and structural effects on upward lightning exposure.

The study employed a two-step numerical framework combining finite-element field simulations with a leader-inception and propagation model to estimate the effective heights of mountaintop towers exposed to self-initiated upward flashes. In addition, the framework reproduced the effective height values reported by Zhou et al. [

4] within approximately 10%, confirming the physical consistency of the approach and validating the use of the stabilization field as a unified criterion for effective-height determination. While Zhou’s analytical formulation provides a valuable reference, it relies on axisymmetric field assumptions and a simplified leader-propagation geometry. The FEM-based three-dimensional framework developed in this work resolves local field distortions caused by mountain shape and tower morphology, offering greater physical fidelity and the flexibility to extend analyses to complex terrain and non-ideal geometries.

In comparison, Shindo’s electrostatic equivalence method [

5] reproduced the general trend of increasing effective height with tower elevation but systematically overestimated the values, particularly for broad-mountain towers such as Gaisberg and Monte Orsa. The model performs reasonably for steeper or more isolated sites, including, for example, Peissenberg and Cachimbo, where the influence of surface-charge redistribution is less pronounced; but its simplified treatment of field concentration and absence of leader physics limits its quantitative accuracy.

The empirical formulations of Eriksson [

3] and Pierce [

2] exhibited deviations of 40–70% for several sites, underscoring the restricted generality of relations derived from long-term, site-specific lightning statistics when applied to complex or elevated terrain.

These results provide a validated foundation for improved exposure and risk evaluation methodologies for mountaintop installations under self-initiated upward lightning conditions.