Mercury Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North Macedonia: Insights from an 18-Year Moss Biomonitoring Programme

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

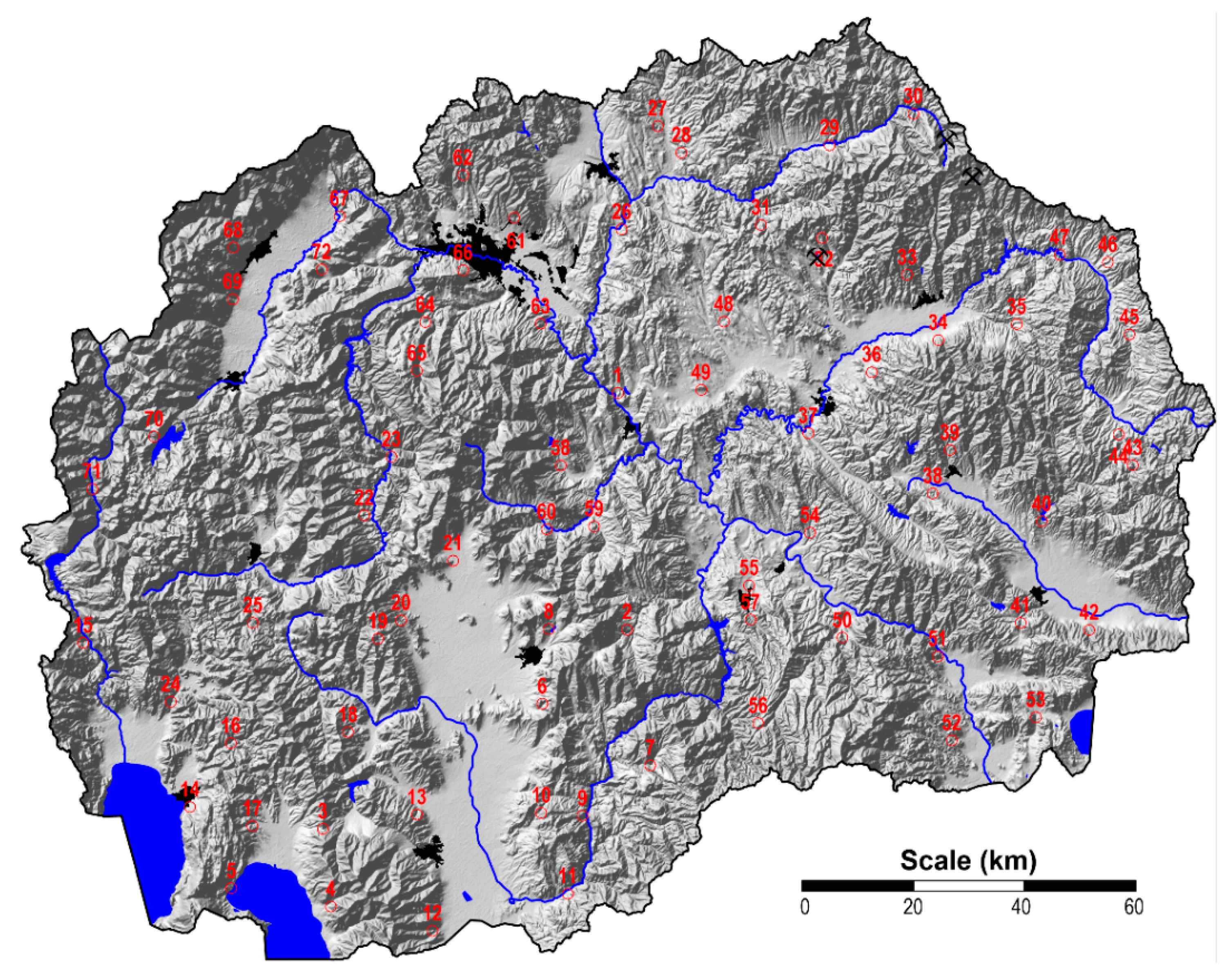

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling, Sample Preparation, and Instrumentation

2.3. Quality Control

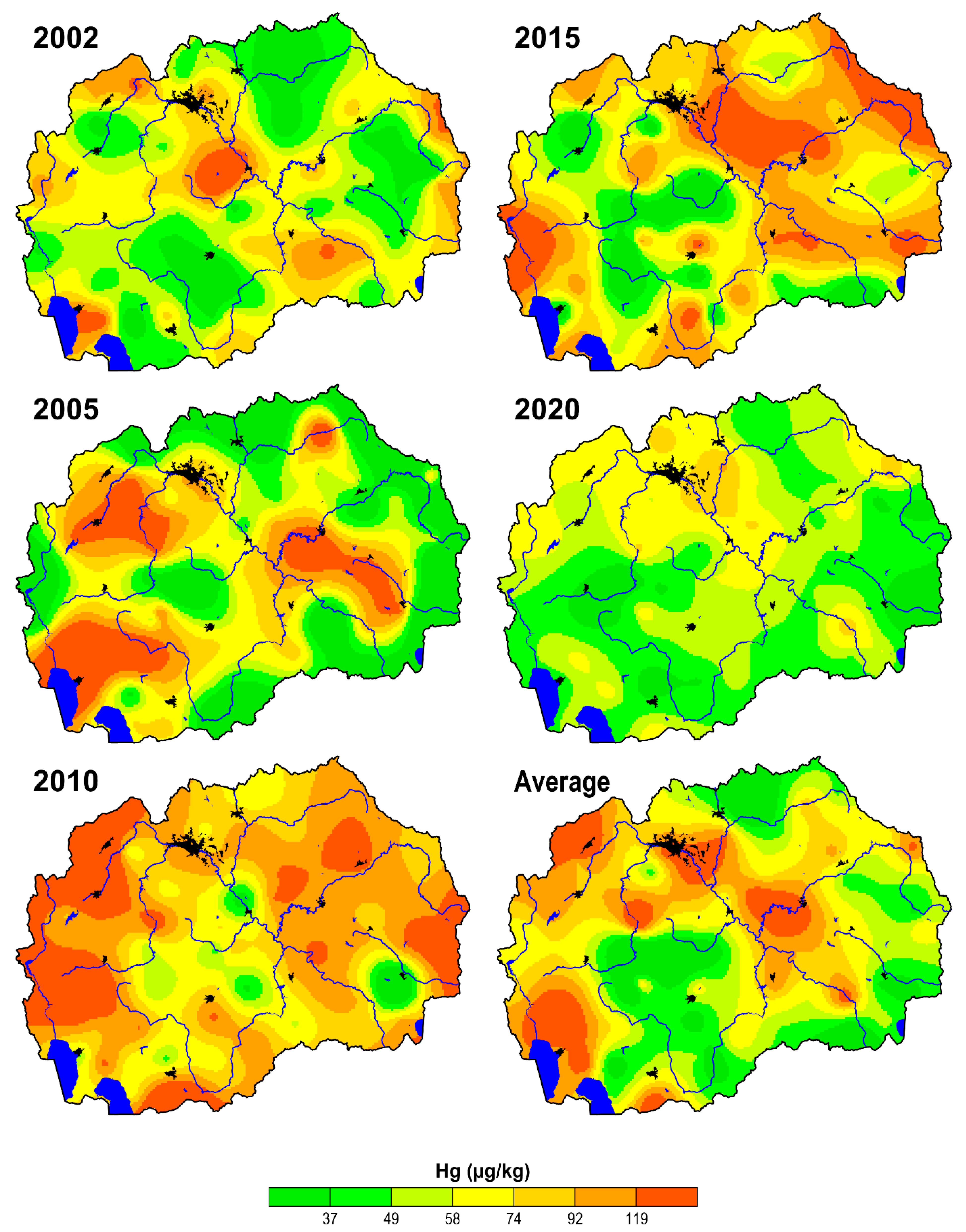

2.4. Statistical Methods and Mapping

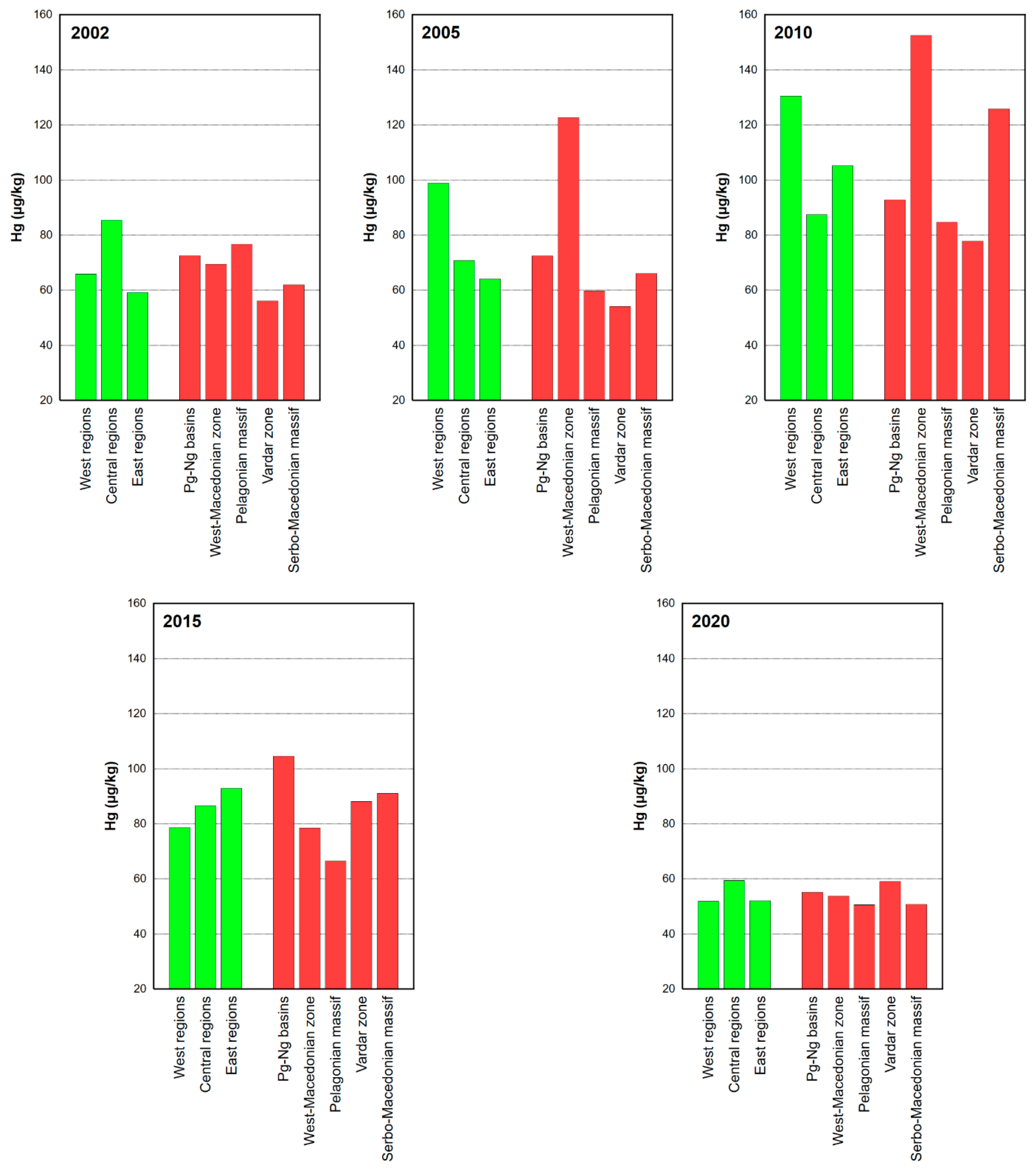

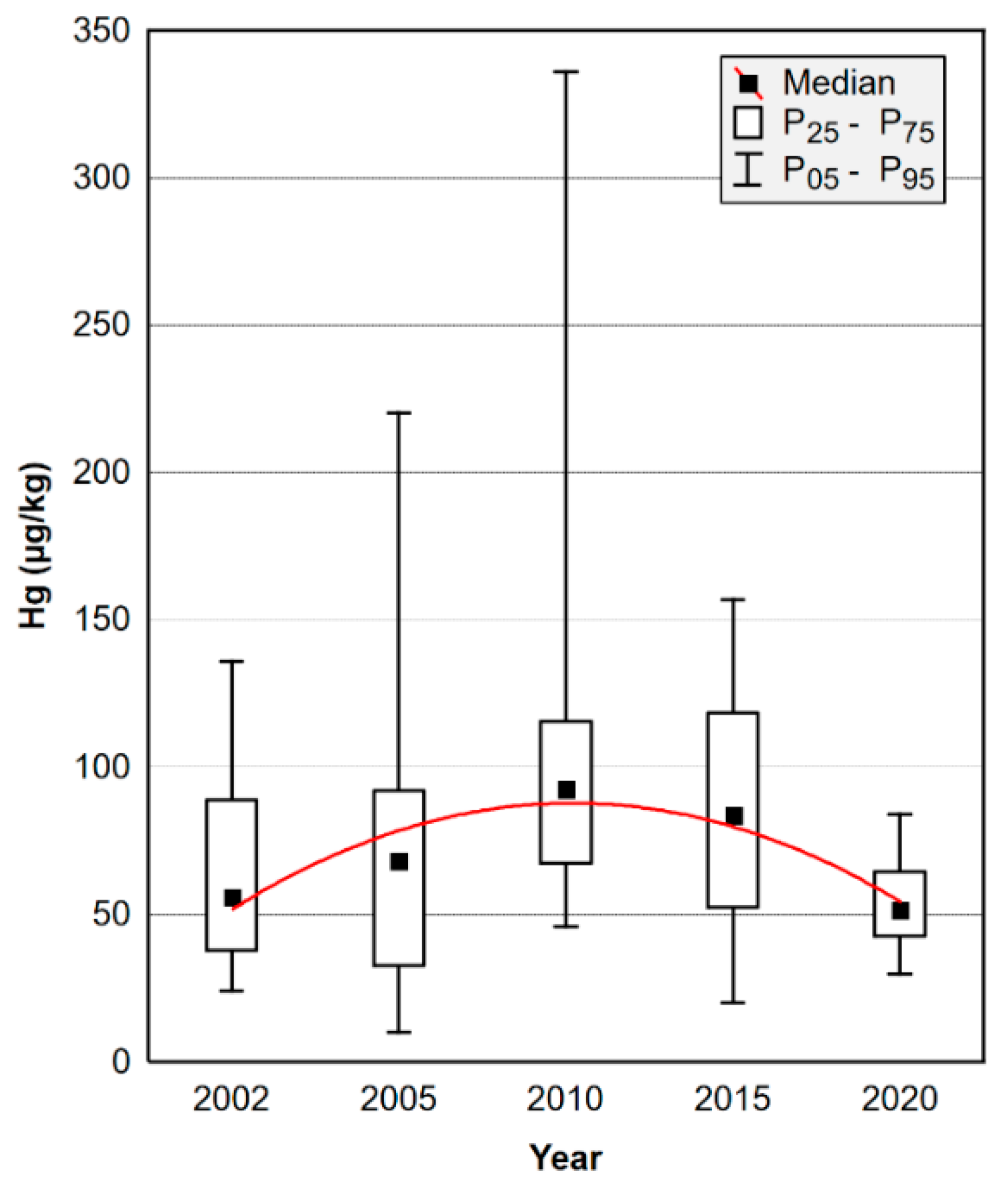

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Health Effects of Particulate Matter; UN City: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Particulate Matter (PM) Pollution. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The Contribution of Outdoor Air Pollution Sources to Premature Mortality on a Global Scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauli-Sajani, S.; Thunis, P.; Pisoni, E.; Bessagnet, B.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; De Meij, A.; Pekar, F.; Vignati, E. Reducing Biomass Burning Is Key to Decrease PM2.5 Exposure in European Cities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, M.; Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pagani, F.; Becker, W.; Banja, M.; Schaaf, E.; Simonati, A. EDGAR v8.1 Global Mercury Emissions; European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC): Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. International Actions Reducing Mercury Emissions and Use. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/international-actions-reducing-mercury-emissions-and-use (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- UNEP. Global Mercury Assessment 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/global-mercury-assessment-2018 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Brocza, F.M.; Rafaj, P.; Sander, R.; Wagner, F.; Jones, J.M. Global Scenarios of Anthropogenic Mercury Emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 7385–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyman, B.M.; Streets, D.G.; Thackray, C.P.; Olson, C.L.; Schaefer, K.; Sunderland, E.M. Projecting Global Mercury Emissions and Deposition Under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2023EF004231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, N.; Costa, P.; Pacyna, J.M.; Ferrara, R. Mercury Emissions to the Atmosphere from Natural and Anthropogenic Sources in the Mediterranean Region. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Minamata Convention on Mercury: Progress Report 2024; UNEP: Athens, Greece, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Ayensu, W.K.; Ninashvili, N.; Sutton, D. Review: Environmental Exposure to Mercury and Its Toxicopathologic Implications for Public Health. Environ. Toxicol. 2003, 18, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühling, Å.; Tyler, G. An Ecological Approach to the Lead Problem. Bot. Not. 1968, 121, 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bargagli, R.; Monaci, F.; Borghini, F.; Bravi, F.; Agnorelli, C. Mosses and Lichens as Biomonitors of Trace Metals. A Comparison Study on Hypnum Cupressiforme and Parmelia Caperata in a Former Mining District in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, L.; Bandoni, E.; Sanità di Toppi, L. Lichens and Mosses as Biomonitors of Indoor Pollution. Biology 2023, 12, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K. Impacts of Particulate Matter Pollution on Plants: Implications for Environmental Biomonitoring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 129, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Fan, M.; Hu, R.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y. Mosses Are Better than Leaves of Vascular Plants in Monitoring Atmospheric Heavy Metal Pollution in Urban Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.-T.; Wang, X.-M.; Wu, N.; Chen, L.-X.; Yuan, M.; Hu, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-E. Temporal and Spatial Biomonitoring of Atmospheric Heavy Metal Pollution Using Moss Bags in Xichang. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, D.; Liu, Y.; Ren, L.; Huo, J.; Zhao, J.; Lu, R.; Huang, Y.; Duan, L. Assessment of Atmospheric Heavy Metal Pollution in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Using Mosses as Biomonitor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S.; Adamo, P.; Monaci, F.; Pittao, E.; Tretiach, M.; Bargagli, R. Bags with Oven-Dried Moss for the Active Monitoring of Airborne Trace Elements in Urban Areas. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 2798–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, A.; Aboal, J.R.; Carballeira, A.; Giordano, S.; Adamo, P.; Fernández, J.A. Moss Bag Biomonitoring: A Methodological Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 432, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, H.; Paturi, P.; Mäkinen, J. Moss Bag (Sphagnum Papillosum) Magnetic and Elemental Properties for Characterising Seasonal and Spatial Variation in Urban Pollution. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, H.; Mäkinen, J. Comparison of Traditional Moss Bags and Synthetic Fabric Bags in Magnetic Monitoring of Urban Air Pollution. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fačkovcová, Z.; Vannini, A.; Monaci, F.; Grattacaso, M.; Paoli, L.; Loppi, S. Effects of Wood Distillate (Pyroligneous Acid) on Sensitive Bioindicators (Lichen and Moss). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 204, 111117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Buse, A.; Büker, P.; Norris, D.; Mills, G.; Williams, B.; Reynolds, B.; Ashenden, T.W.; Rühling, Å.; Steinnes, E. Heavy Metal Concentrations in European Mosses: 2000/2001 Survey. J. Atmos. Chem. 2004, 49, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Mills, G.; Hayes, F. Air Pollution and Vegetation: ICP Vegetation Annual Report 2003/2004; Martinez-Abaigar, J.D., Aboal, J., Alber, R., Alonso, E.I.G., Akinshina, N., Aleksiayenak, Y., Eds.; ICP Vegetation Coordination Centre: Bangor, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, S.; Schröder, W.; Schmalfuss, R.; Saathoff, M.; Harmens, H.; Mills, G.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Barandovski, L.; Blum, O.; Carballeira, A.; et al. Modelling Spatial Patterns of Correlations between Concentrations of Heavy Metals in Mosses and Atmospheric Deposition in 2010 across Europe. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Norris, D.A.; Sharps, K.; Mills, G.; Alber, R.; Aleksiayenak, Y.; Blum, O.; Cucu-Man, S.-M.; Dam, M.; De Temmerman, L.; et al. Heavy Metal and Nitrogen Concentrations in Mosses Are Declining across Europe Whilst Some “Hotspots” Remain in 2010. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 200, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontasyeva, M.; Harmens, H.; Uzhinsky, A.; Abdusamadzoda, D.; Abdushukurov, D.; Adkinson, K.; Aherne, J.; Alber, Y.; Aleksiayenak, Y.; Allajbeu, S.; et al. Mosses as Biomonitors of Air Pollution: 2015/2016 Survey on Heavy Metals, Nitrogen and POPs in Europe and Beyond; Joint Institute for Nuclear Research JINR: Dubna, Russia, 2020; ISBN 978-5-9530-0508-1. [Google Scholar]

- Harmens, H.; Norris, D.A.; Koerber, G.R.; Buse, A.; Steinnes, E.; Rühling, Å. Temporal Trends in the Concentration of Arsenic, Chromium, Copper, Iron, Nickel, Vanadium and Zinc in Mosses across Europe between 1990 and 2000. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 6673–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Norris, D.A.; Koerber, G.R.; Buse, A.; Steinnes, E.; Rühling, Å. Temporal Trends (1990–2000) in the Concentration of Cadmium, Lead and Mercury in Mosses across Europe. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, S.; Schröder, W.; Dreyer, A.; Völksen, B. Mapping Spatial and Temporal Trends of Atmospheric Deposition of Nitrogen at the Landscape Level in Germany 2005, 2015 and 2020 and Their Comparison with Emission Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmens, H.; Norris, D.A.; Steinnes, E.; Kubin, E.; Piispanen, J.; Alber, R.; Aleksiayenak, Y.; Blum, O.; Coşkun, M.; Dam, M.; et al. Mosses as Biomonitors of Atmospheric Heavy Metal Deposition: Spatial Patterns and Temporal Trends in Europe. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3144–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargagli, R. Moss and Lichen Biomonitoring of Atmospheric Mercury: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Seoane, R.; Antelo, J.; Fiol, S.; Fernández, J.A.; Aboal, J.R. Unravelling the Metal Uptake Process in Mosses: Comparison of Aquatic and Terrestrial Species as Air Pollution Biomonitors. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 122069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palma, A.; Capozzi, F.; Spagnuolo, V.; Giordano, S.; Adamo, P. Atmospheric Particulate Matter Intercepted by Moss-Bags: Relations to Moss Trace Element Uptake and Land Use. Chemosphere 2017, 176, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.A.; Boquete, M.T.; Carballeira, A.; Aboal, J.R. A Critical Review of Protocols for Moss Biomonitoring of Atmospheric Deposition: Sampling and Sample Preparation. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 517, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandovski, L.; Cekova, M.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Pavlov, S.S.; Stafilov, T.; Steinnes, E.; Urumov, V. Atmospheric Deposition of Trace Element Pollutants in Macedonia Studied by the Moss Biomonitoring Technique. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 138, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandovski, L.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Pavlov, S.; Enimiteva, V. Trends of Atmospheric Deposition of Trace Elements in Macedonia Studied by the Moss Biomonitoring Technique. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2012, 47, 2000–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandovski, L.; Stafilov, T.; Sajn, R.; Frontasyeva, M.; Baceva, K. Air Pollution Study in Macedonia Using a Moss Biomonitoring Technique, ICP-AES and AAS. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2013, 32, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Barandovski, L.; Andonovska, K.B.; Malinovska, S. Moss Biomonitoring of Atmospheric Deposition Study of Minor and Trace Elements in Macedonia. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2018, 11, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafilov, T.; Barandovski, L.; Šajn, R.; Andonovska, K.B. Atmospheric Mercury Deposition in Macedonia from 2002 to 2015 Determined Using the Moss Biomonitoring Technique. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandovski, L.; Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Frontasyeva, M.; Andonovska, K.B. Atmospheric Heavy Metal Deposition in North Macedonia from 2002 to 2010 Studied by Moss Biomonitoring Technique. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačeva Andonovska, K.; Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Jordanoska Shishkoska, B.; Pelivanoska, V.; Barandovski, L. Trends in Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition in Macedonia Studied by Using the Moss Biomonitoring Technique. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajn, R.; Alijagić, J.; Ristović, I. Secondary Deposits as a Potential REEs Source in South-Eastern Europe. Minerals 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimovska, S.; Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Frontasyeva, M. Distribution of Some Natural and Man-Made Radionuclides in Soil from the City of Veles (Republic of Macedonia) and Its Environs. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2010, 138, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Boev, B.; Cvetković, J.; Mukaetov, D.; Andreevski, M.; Lepitkova, S. Distribution of Some Elements in Surface Soil over the Kavadarci Region, Republic of Macedonia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 61, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačeva, K.; Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R.; Tănăselia, C.; Makreski, P. Distribution of Chemical Elements in Soils and Stream Sediments in the Area of Abandoned Sb–As–Tl Allchar Mine, Republic of Macedonia. Environ. Res. 2014, 133, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevski, A. Climate in Macedonia; Kultura: Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stafilov, T.; Šajn, R. Geochemical Atlas of the Republic of Macedonia; Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Ss Cyril and Methodius University: Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2016; ISBN 978-608-4762-04-1. [Google Scholar]

- Steinnes, E.; Rühling, Å.; Lippo, H.; Mäkinen, A. Reference Materials for Large-Scale Metal Deposition Surveys. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 1997, 2, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmens, H.; Mills, G.; Hayes, F. Air Pollution and Vegetation: ICP Vegetation Annual Report 2004/2005; Martinez-Abaigar, J.D., Aboal, J., Alber, R., Alonso, E.I.G., Akinshina, N., Aleksiayenak, Y., Eds.; ICP Vegetation Coordination Centre: Bangor, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harmens, H.; Mills, G.; Hayes, F. Air Pollution and Vegetation: ICP Vegetation Annual Report 2011/2012; Martinez-Abaigar, J.D., Aboal, J., Alber, R., Alonso, E.I.G., Akinshina, N., Aleksiayenak, Y., Eds.; ICP Vegetation Coordination Centre: Bangor, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor, G.W.; Cochran, W.G. Statistical Methods, 6th ed.; The Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.C. Statistics and Data Analysis in Geology, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, M.; Wolfe, D.A.; Chicken, E. Nonparametric Statistical Methods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780470387375. [Google Scholar]

- Statistica (Software), Version 14; TIBCO Software Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2020.

- Matheron, G. Présentation Des Variables Régionalisées. J. La Société Stat. Paris 1966, 107, 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Krige, D.G. A Statistical Approaches to Some Basic Mine Valuation Problems on the Witwatersrand. J. Chem. Metall. Min. Soc. S. Afr. 1951, 52, 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Krige, D.G. On the Departure of Ore Value Distributions from Lognormal Models in South African Gold Mines. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 1960, 60, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Lin, H.S. Comparing Ordinary Kriging and Regression Kriging for Soil Properties in Contrasting Landscapes. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, T.; Lian, H.; Ding, Z. Bioaccessibility and Health Risk of Arsenic, Mercury and Other Metals in Urban Street Dusts from a Mega-City, Nanjing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Webster, R. A Tutorial Guide to Geostatistics: Computing and Modelling Variograms and Kriging. Catena 2014, 113, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Olson, J.R.; Bian, L.; Rogerson, P.A. Analysis of Heavy Metal Sources in Soil Using Kriging Interpolation on Principal Components. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4999–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, Q.; Shi, Y.; Guo, G.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, C. Spatial Distribution Prediction of Soil As in a Large-Scale Arsenic Slag Contaminated Site Based on an Integrated Model and Multi-Source Environmental Data. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Kim, N.; Choo, H. Kriging Interpolation for Constructing Database of the Atmospheric Refractivity in Korea. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Heavy Metal Emission in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/heavy-metal-emissions-in-europe (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Hayes, F.; Sharps, K.; Participants of the Moss Survey. Mosses as Biomonitors of Air Pollution: 2020/2021 Survey on Heavy Metals, Nitrogen and POPs in Europe and Beyond; Hayes, F., Sharps, K., Eds.; ICP Vegetation Coordination Centre, UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Environment Centre: Bangor, Wales, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Decisions Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention on Mercury at Its Fifth Meeting; UNEP: Athens, Greece, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Year | X | XBC | Md | Min | Max | P25 | P75 | S | CV | MAD | QCD | A | E | ABC | EBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 68 | 58 | 56 | 18 | 264 | 38 | 89 | 40 | 59 | 20 | 40 | 2.03 | 7.08 | 0.01 | −0.36 |

| 2005 | 80 | 60 | 68 | 10 | 416 | 33 | 92 | 72 | 89 | 31 | 48 | 2.40 | 7.69 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| 2010 | 112 | 91 | 93 | 10 | 595 | 68 | 116 | 94 | 84 | 24 | 26 | 3.57 | 14.17 | −0.03 | 4.23 |

| 2015 | 85 | 79 | 84 | 20 | 253 | 53 | 118 | 47 | 56 | 33 | 39 | 0.55 | 0.70 | −0.11 | −0.49 |

| 2020 | 54 | 52 | 52 | 27 | 96 | 43 | 65 | 15 | 28 | 10 | 20 | 0.61 | 0.14 | −0.00 | −0.22 |

| Zone | 2002 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | |||||

| Western regions | 66 | 99 | 131 | 79 | 52 |

| Central regions | 85 | 71 | 87 | 87 | 59 |

| Eastern regions | 59 | 64 | 105 | 93 | 52 |

| Geological formations | |||||

| Paleogene–Neogene basins | 73 | 72 | 93 | 104 | 55 |

| West Macedonian zone | 69 | 123 | 152 | 79 | 54 |

| Pelagonian massif | 77 | 60 | 85 | 66 | 51 |

| Vardar zone | 56 | 54 | 78 | 88 | 59 |

| Serbo-Macedonian massif | 62 | 66 | 126 | 91 | 51 |

| Degree of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Squares | F Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 4 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 9.47 * |

| Regions | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 NS |

| Geoformations | 4 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.61 * |

| Error | 348 | 1.23 | 0.00 | – |

| Total | 358 | 1.41 | – | – |

| 2002 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2005 | −0.01 | 1.00 | |||

| 2010 | −0.09 | −0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2015 | 0.06 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |

| 2020 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 1.00 |

| 2002 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Andonovska, K.B.; Šajn, R.; Alijagić, J.; Stafilov, T.; Barandovski, L. Mercury Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North Macedonia: Insights from an 18-Year Moss Biomonitoring Programme. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010012

Andonovska KB, Šajn R, Alijagić J, Stafilov T, Barandovski L. Mercury Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North Macedonia: Insights from an 18-Year Moss Biomonitoring Programme. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndonovska, Katerina Bačeva, Robert Šajn, Jasminka Alijagić, Trajče Stafilov, and Lambe Barandovski. 2026. "Mercury Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North Macedonia: Insights from an 18-Year Moss Biomonitoring Programme" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010012

APA StyleAndonovska, K. B., Šajn, R., Alijagić, J., Stafilov, T., & Barandovski, L. (2026). Mercury Pollution in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North Macedonia: Insights from an 18-Year Moss Biomonitoring Programme. Atmosphere, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010012