Validation Testing of Continuous Laser Methane Monitoring at Operational Oil and Gas Production Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LongPath Continuous Emissions Measurement and Monitoring

2.2. Operational Oil and Gas Sites and Validation Test Locations

2.3. Leak Detection Classification Schema

2.4. Validation Testing: Operational Emissions Verification

2.5. Validation Testing: Operational Controlled Release Challenge Testing

2.6. Validation Testing: Third-Party Controlled Release Testing

2.7. Quantification of Site-Wide Emissions, Fugitive Emissions, and Controlled Releases

3. Results

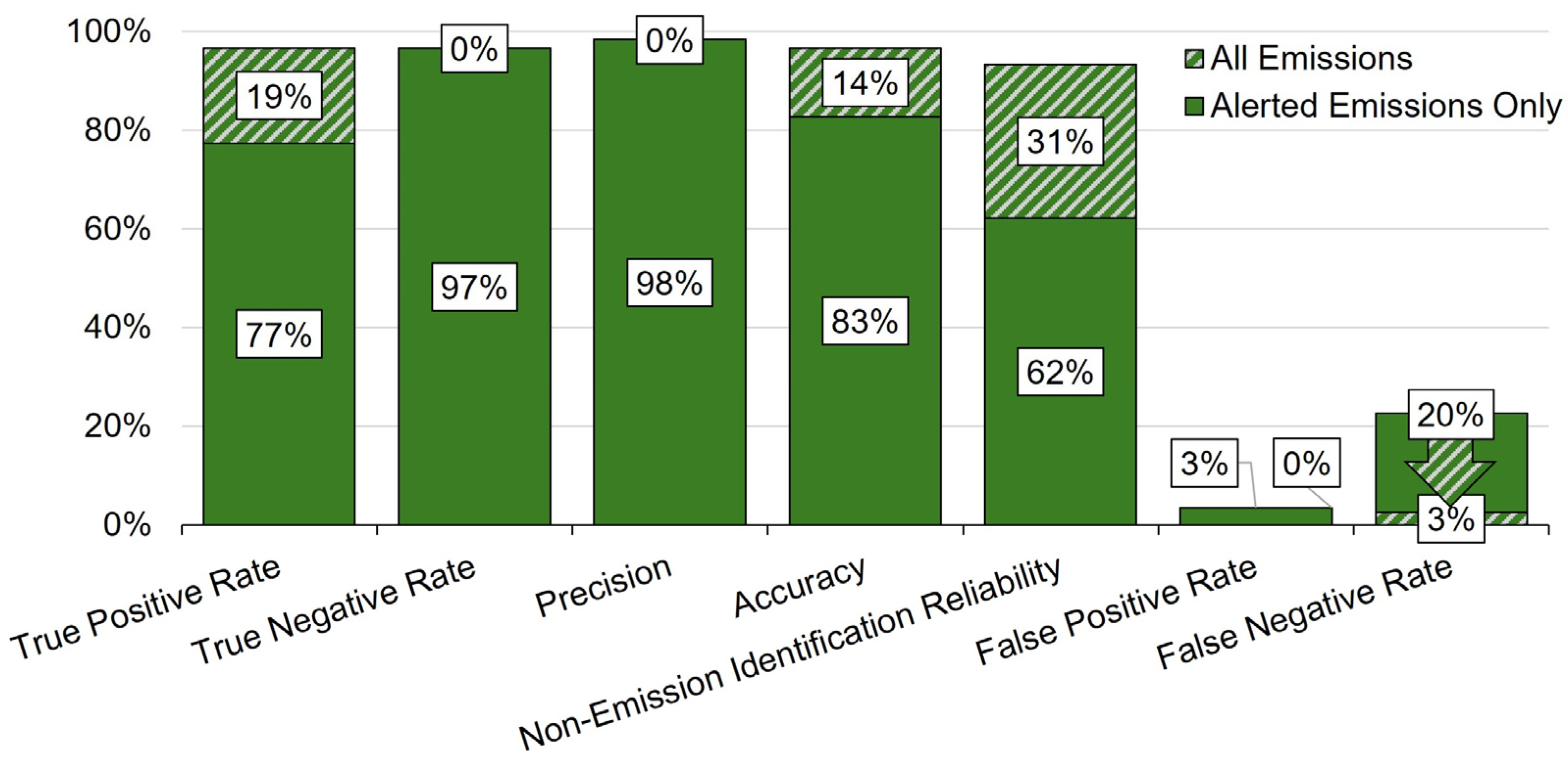

3.1. Detection and Quantification Validation: Operational Emissions

3.2. Alert Frequency and Time-to-Alert

3.3. Detection and Quantification Validation: Challenge Testing

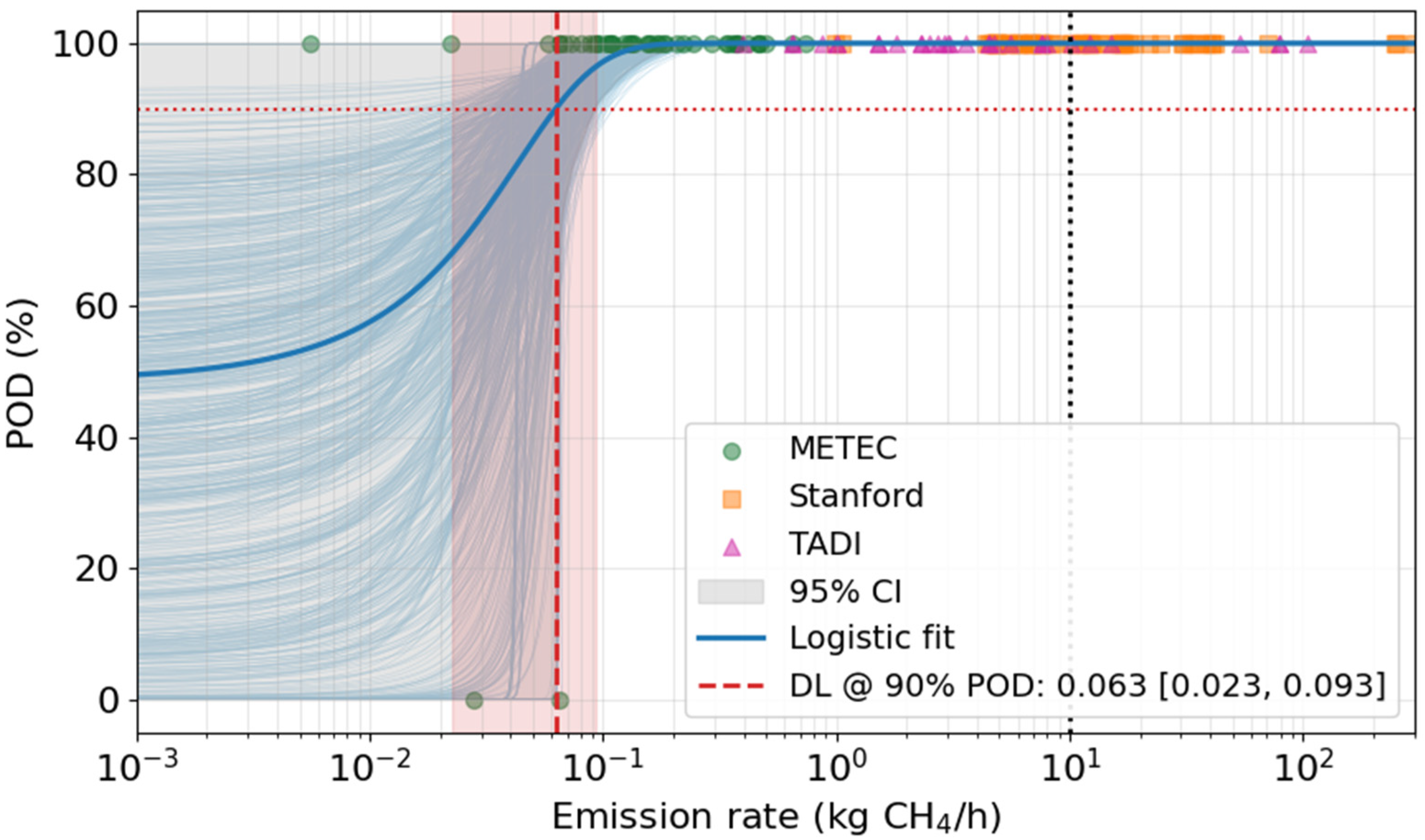

3.4. Detection Validation: Third-Party Test Facility Blind Test Controlled Releases

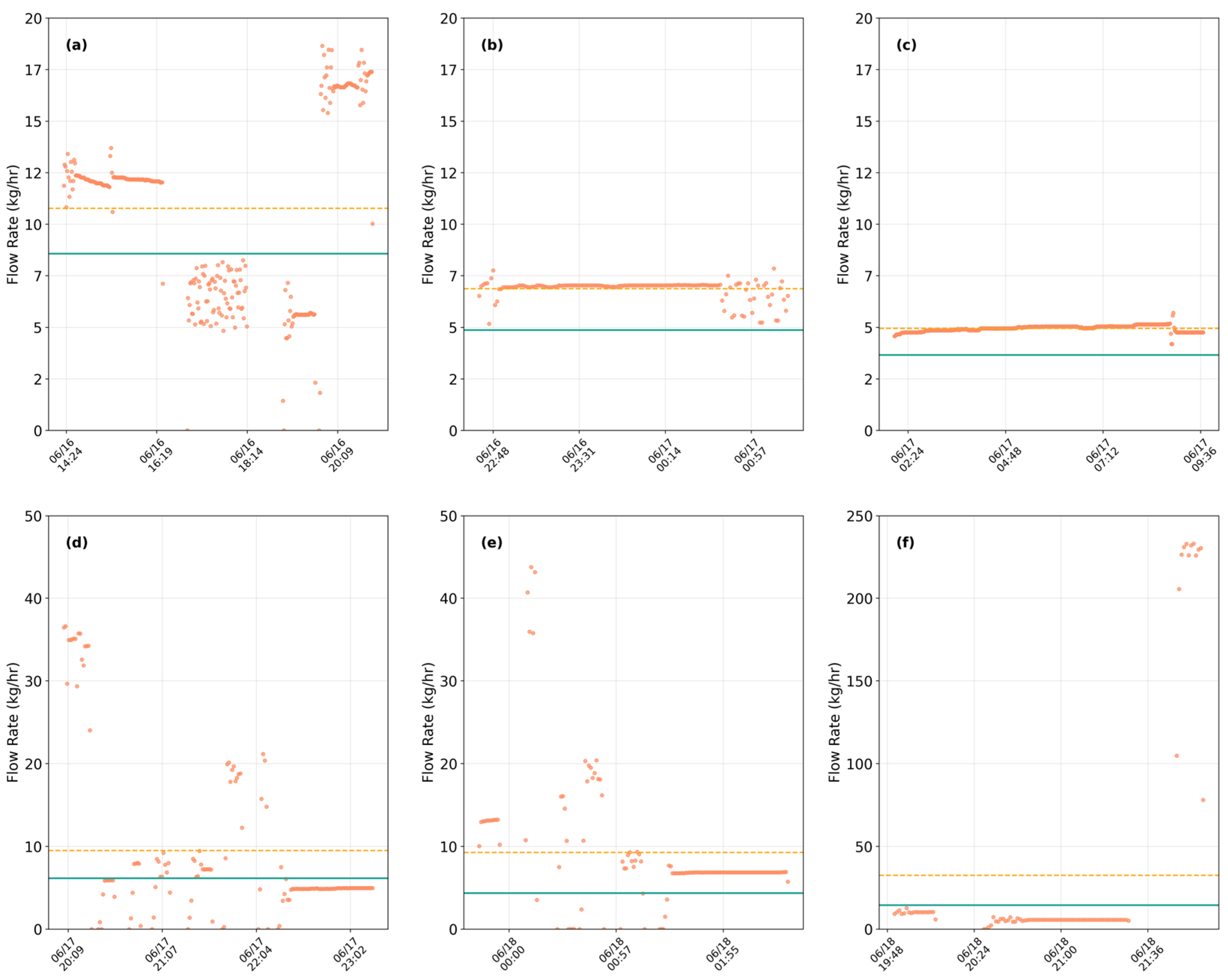

3.5. Quantification Validation: Third-Party Blind and Challenge Test Controlled Releases

3.6. Quantification Agreement Between Independent Laser Systems

3.7. OGMP 2.0 Level 5 Quantification

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Pean, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saunois, M.; Martinez, A.; Poulter, B.; Zhang, Z.; Raymond, P.A.; Regnier, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Patra, P.K.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Global Methane Budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1873–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodshire, A.; Duggan, G.; Zimmerle, D.; Santos, A.; McArthur, T.; Bylsma, J.; Alden, C.; Youngquist, D.; White, A.; Rieker, G. Intermittent Emissions from Oil and Gas Operations: Implications for Detection Effectiveness from Periodic Leak Detection Surveys. ACS EST Air 2025, 2, 2776–2785. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon, J.L.; Sorensen, C.; Lemery, J.; Workman, C.F.; Linstadt, H.; Bazilian, M.D. Managing Upstream Oil and Gas Emissions: A Public Health Oriented Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusworth, D.H.; Duren, R.M.; Thorpe, A.K.; Olson-Duvall, W.; Heckler, J.; Chapman, J.W.; Eastwood, M.L.; Helmlinger, M.C.; Green, R.O.; Asner, G.P.; et al. Intermittency of Large Methane Emitters in the Permian Basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. MATM-005: LongPath Technologies Alternative Test Method; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Cutting-Edge Emissions Monitoring Solutions|LongPath Technologies. Available online: https://www.longpathtech.com (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Zimmerle, D.; Bell, C.; Emerson, E.; Levin, E.; Cheptonui, F.; Day, R. Advancing Development of Emissions Detection: DE-FE0031873 Final Report; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, S.; Alden, C.B.; Wright, R.; Cossel, K.; Baumann, E.; Truong, G.-W.; Giorgetta, F.; Sweeney, C.; Newbury, N.R.; Prasad, K.; et al. Regional Trace-Gas Source Attribution Using a Field-Deployed Dual Frequency Comb Spectrometer. Optica 2018, 5, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieker, G.B.; Giorgetta, F.R.; Swann, W.C.; Kofler, J.; Zolot, A.M.; Sinclair, L.C.; Baumann, E.; Cromer, C.; Petron, G.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Frequency-Comb-Based Remote Sensing of Greenhouse Gases over Kilometer Air Paths. Optica 2014, 1, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, C.B.; Coburn, S.C.; Wright, R.J.; Baumann, E.; Cossel, K.; Perez, E.; Hoenig, E.; Prasad, K.; Coddington, I.; Rieker, G.B. Single-Blind Quantification of Natural Gas Leaks from 1 Km Distance Using Frequency Combs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 2908–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alden, C.B.; Wright, R.J.; Coburn, S.C.; Caputi, D.; Wendland, G.; Rybchuk, A.; Conley, S.; Faloona, I.; Rieker, G.B. Temporal Variability of Emissions Revealed by Continuous, Long-Term Monitoring of an Underground Natural Gas Storage Facility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14589–14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alden, C.B.; Chipponeri, D.; Youngquist, D.; Rieker, G.B. Access to Monitoring Data Reduces Methane Emissions at Operational Oil and Gas Facilities. Earth arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; El Abbadi, S.H.; Sherwin, E.D.; Burdeau, P.M.; Rutherford, J.S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Brandt, A.R. Comparing Continuous Methane Monitoring Technologies for High-Volume Emissions: A Single-Blind Controlled Release Study. ACS EST Air 2024, 1, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Ilonze, C.; Duggan, A.; Zimmerle, D. Performance of Continuous Emission Monitoring Solutions under a Single-Blind Controlled Testing Protocol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5794–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Standards of Performance for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources and Emissions Guidelines for Existing Sources: Oil and Natural Gas Sector Climate Review; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Zimmerle, D.; Levin, E.; Emerson, E.; Juery, C.; Marcarian, X.; Blandin, V. Controlled Test Protocol: Emission Detection and Quantification Protocol. Available online: https://metec.colostate.edu/aded/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Coburn, S.; Alden, C.; Wright, R.; Wendland, G.; Rybchuk, A.; Seitz, N.; Coddington, I.; Rieker, G. Long Distance Continuous Methane Emissions Monitoring with Dual Frequency Comb Spectroscopy: Deployment and Blind Testing in Complex Emissions Scenarios. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonze, C.; Wang, J.; Ravikumar, A.P.; Zimmerle, D. Methane Quantification Performance of the Quantitative Optical Gas Imaging (QOGI) System Using Single-Blind Controlled Release Assessment. Sensors 2024, 24, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homepage|The Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0. Available online: https://www.ogmpartnership.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Conrad, B.M.; Tyner, D.R.; Johnson, M.R. Robust Probabilities of Detection and Quantification Uncertainty for Aerial Methane Detection: Examples for Three Airborne Technologies. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 288, 113499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A Solution to the Problem of Separation in Logistic Regression. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckland, S.T.; Anderson, D.R.; Burnham, K.P.; Laake, J.L.; Borchers, D.L.; Thomas, L. Introduction to Distance Sampling: Estimating Abundance of Biological Populations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-19-850649-2. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, K.; Alaeddini, A. A Truncated Logistic Regression Model in Probability of Detection Evaluation. Qual. Eng. 2011, 23, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LongPath Laser Node | Number of Sites | Site Types | Duration of Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basin1-Node1 | 8 | 7 Production Facilities and 1 Well Site | 10 months |

| Basin1-Node2 | 2 | 1 Production Facility and 1 Processing Plant | 10 months |

| Basin2-Node1 | 10 | 4 Production Facilities and 6 Well Sites | 9 months |

| Basin2-Node2 | 13 | 5 Production Facilities and 8 Well Sites | 9 months |

| Basin2-Node3 | 18 | 10 Production Facilities and 8 Well Sites | 9 months |

| Result Classification | Alert Status | Emissions Status |

|---|---|---|

| True Positive | Alert Sent | Emissions Abnormal |

| True Negative | No Alert Sent | Emissions Normal |

| False Positive | Alert Sent | Emissions Normal |

| False Negative | No Alert Sent | Emissions Abnormal |

| Result Label | Formulation (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| True Negative Rate (Non-Emission Accuracy) | The percentage of correctly identified operator-confirmed non-emission periods. | |

| Precision (Emission Identification Reliability) | The percentage of reported emissions that were correctly identified according to operator confirmation, or the reliability of the system in reporting emission detection. | |

| Accuracy | The percentage of system reports that agree with the operator-confirmed state of emissions. | |

| Non-Emission Identification Reliability | The percentage of reported periods correctly identified as non-emission according to operator confirmation. | |

| False Positive Rate | The percentage of emission events with operator confirmation of no abnormal emissions. | |

| False Negative Rate | The percentage of emission events that were not reported but were confirmed by the operator. |

| Facility | Node 1 | Node 2 | Node 3 | Test Nodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility 2 | Basin2-Node1-Facility2 | --- | Basin2-Node3-Facility2 |

|

| 940 m | 1200 m | |||

| Facility 3 | --- | Basin2-Node2-Facility3 | Basin2-Node3-Facility3 |

|

| 1926 m | 1439 m | |||

| Facility 9 | --- | Basin2-Node2-Facility9 | Basin2-Node3-Facility9 |

|

| 1857 m | 2603 m | |||

| Facility 10 | --- | Basin2-Node2-Facility10 | Basin2-Node3-Facility10 |

|

| 1848 m | 2411 m |

| Basin | Facility | Node | Min (kg hr−1) | Q1 (kg hr−1) | Median (kg hr−1) | Symmetric Difference Median (%) | Q3 (kg hr−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin 2 | Facility 2 | Node 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.40 [0.00, 3.20] | 28.60% | 0.7 | |

| Node 3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.30 [0.00, 2.98] | 0.8 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 3 | Node 2 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.40 [0.00, 49.48] | 80.90% | 2.6 | |

| Node 3 | 0 | 2 | 3.30 [0.00, 85.55] | 5.4 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 9 | Node 2 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.80 [0.14, 4.31] | 57.10% | 2.5 | |

| Node 3 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.00 [0.00, 3.00] | 1.7 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 10 | Node 2 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 7.25 [1.84, 17.05] | 48.90% | 9.4 | |

| Node 3 | 0 | 2.3 | 4.40 [0.37, 14.98] | 7.2 | ||||

| Basin | Facility | Node | Max (kg hr−1) | Mean (kg hr−1) | Symmetric Difference Mean (%) | Std Dev (kg hr−1) | n | Spearman Corr. |

| Basin 2 | Facility 2 | Node 1 | 6.7 | 0.61 [0.00, 3.20] | 1.60% | 0.9 | 160 | R = 0.2 (p = 0.01) |

| Node 3 | 5.2 | 0.62 [0.00, 2.98] | 0.9 | 157 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 3 | Node 2 | 366.3 | 6.96 [0.00, 49.48] | 53.30% | 34.9 | 149 | R = 0.6 (p > 0.01) |

| Node 3 | 440.6 | 12.02 [0.00, 85.55] | 48 | 146 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 9 | Node 2 | 7.4 | 1.82 [0.14, 4.31] | 43.50% | 1.2 | 160 | R = 0.5 (p < 0.01) |

| Node 3 | 3.8 | 1.17 [0.00, 3.00] | 0.9 | 124 | ||||

| Basin 2 | Facility 10 | Node 2 | 28.4 | 7.70 [1.84, 17.05] | 37.30% | 4.4 | 160 | R = 0.4 (p < 0.01) |

| Node 3 | 19.2 | 5.28 [0.37, 14.98] | 3.7 | 118 | ||||

| Basin | Facility | Node | Total Emissions Based on Mean (t) | Total Emissions Based on Median (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin 2 | Facility 2 | Node 1 | 2.36 [0.00, 12.30] | 1.54 [0.00, 12.30] |

| Node 3 | 2.37 [0.00, 11.44] | 1.15 [0.00, 11.44] | ||

| Basin 2 | Facility 3 | Node 2 | 26.71 [0.00, 190.00] | 5.38 [0.00, 190.00] |

| Node 3 | 46.14 [0.00, 328.51] | 12.67 [0.00, 328.51] | ||

| Basin 2 | Facility 9 | Node 2 | 6.98 [0.53, 16.56] | 6.91 [0.53, 16.56] |

| Node 3 | 4.47 [0.00, 11.52] | 3.84 [0.00, 11.52] | ||

| Basin 2 | Facility 10 | Node 2 | 29.58 [7.06, 65.47] | 27.84 [7.06, 65.47] |

| Node 3 | 20.26 [1.40, 57.53] | 16.90 [1.40, 57.53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alden, C.B.; Chipponeri, D.; Youngquist, D.; Krough, B.; Makowiecki, A.; Wilson, D.; Rieker, G.B. Validation Testing of Continuous Laser Methane Monitoring at Operational Oil and Gas Production Facilities. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121409

Alden CB, Chipponeri D, Youngquist D, Krough B, Makowiecki A, Wilson D, Rieker GB. Validation Testing of Continuous Laser Methane Monitoring at Operational Oil and Gas Production Facilities. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121409

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlden, Caroline B., Doug Chipponeri, David Youngquist, Brad Krough, Amanda Makowiecki, David Wilson, and Gregory B. Rieker. 2025. "Validation Testing of Continuous Laser Methane Monitoring at Operational Oil and Gas Production Facilities" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121409

APA StyleAlden, C. B., Chipponeri, D., Youngquist, D., Krough, B., Makowiecki, A., Wilson, D., & Rieker, G. B. (2025). Validation Testing of Continuous Laser Methane Monitoring at Operational Oil and Gas Production Facilities. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121409