Contribution of Leading Natural Climate Variability Modes to Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic in the Early 20th Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Internal Climate Variability on the Arctic SAT Variations

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Methods

4. Results

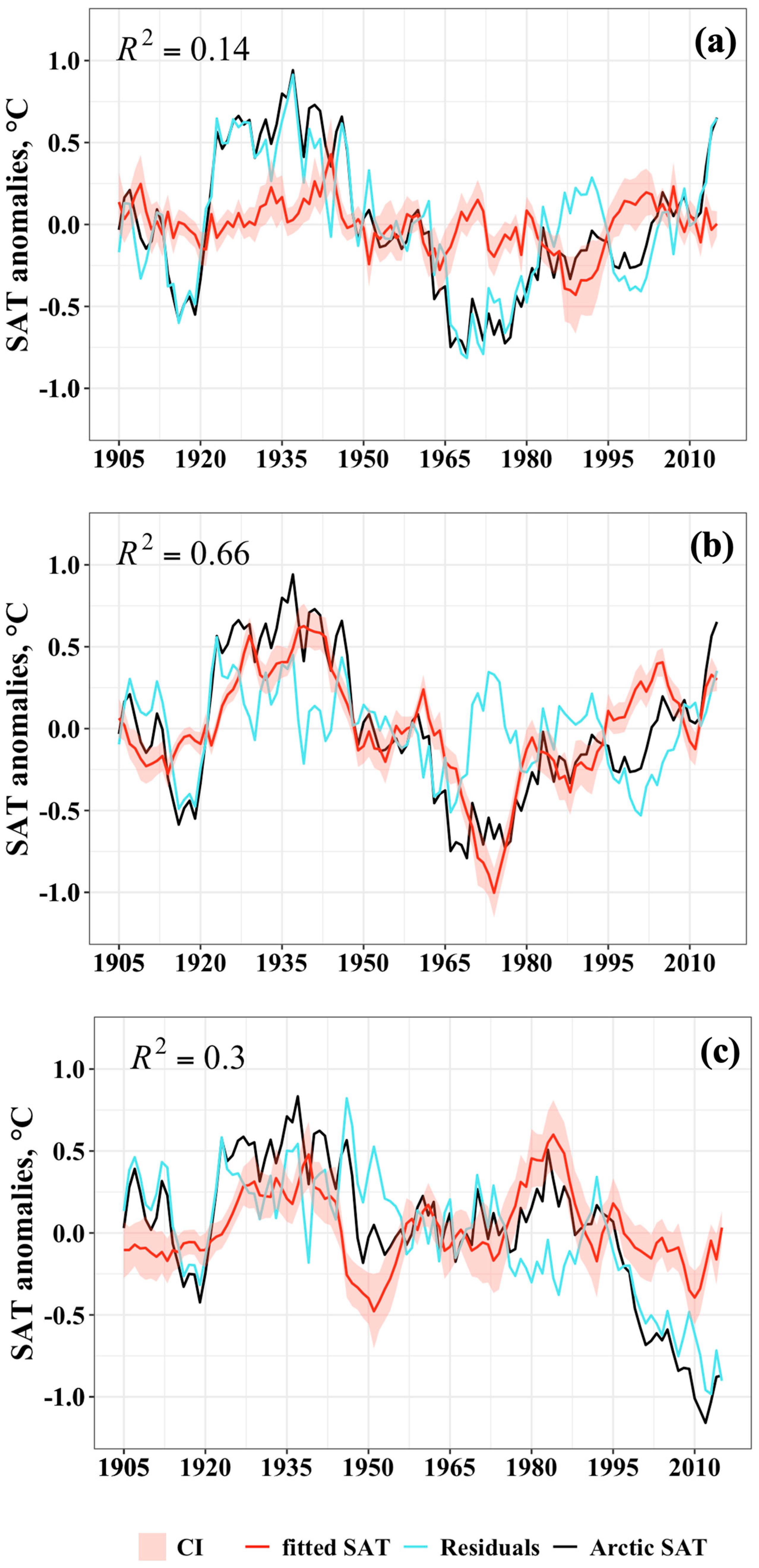

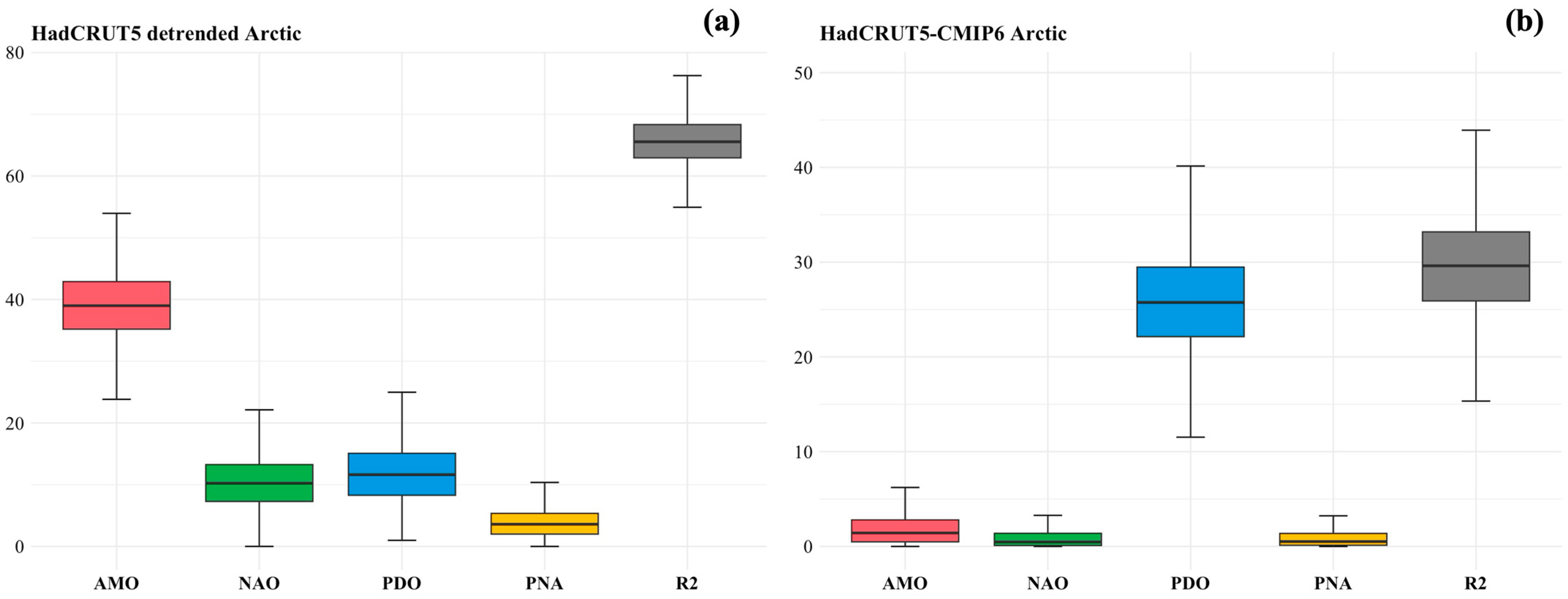

4.1. Contributions of the Leading Atmosphere–Ocean Variability Modes to the Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic

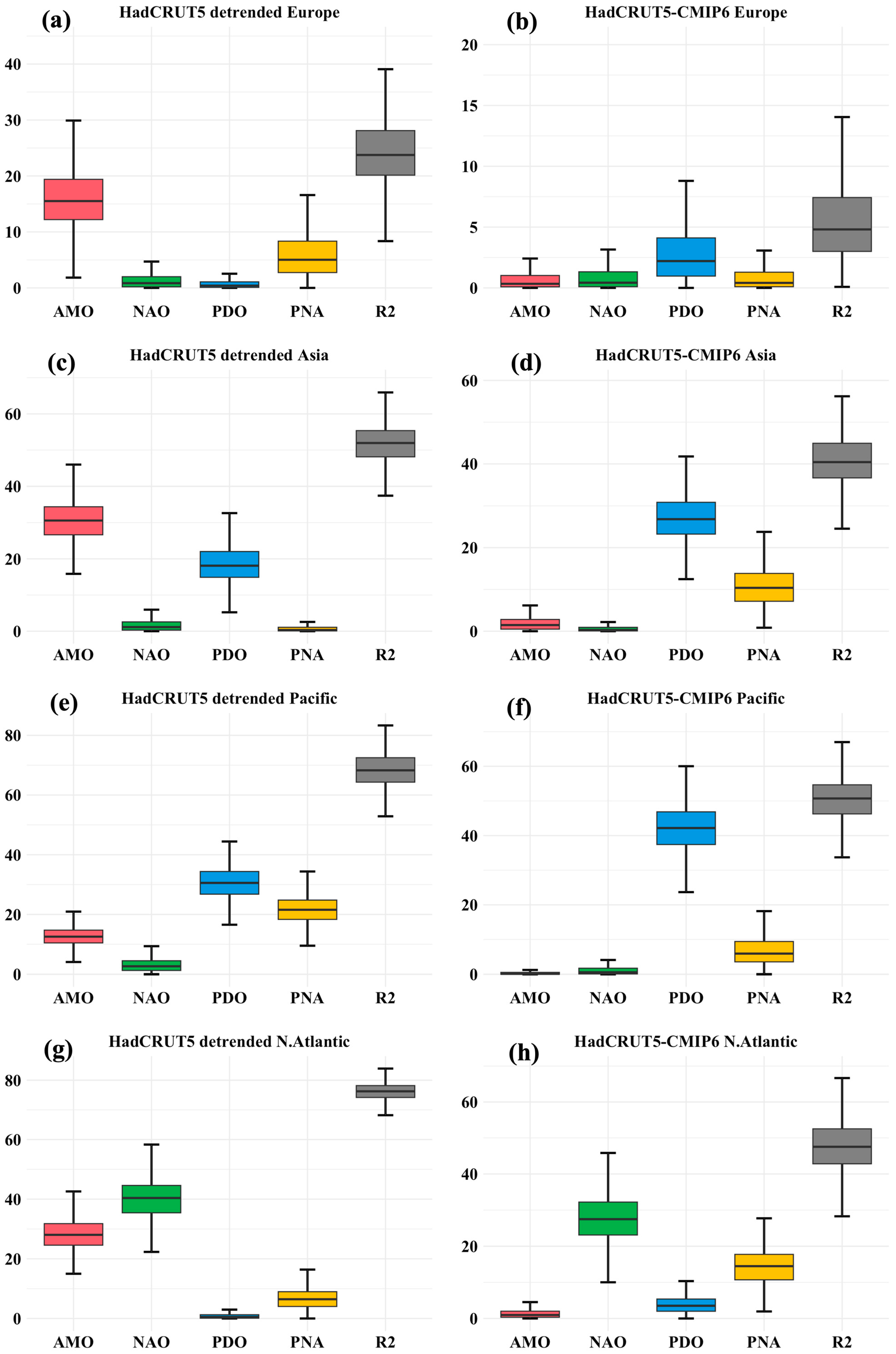

4.2. Assessment of the Potential Contribution of the Leading Modes of Atmosphere–Ocean Variability in Different Sectors of the Arctic

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bengtsson, L.; Semenov, V.A.; Johannessen, O.M. The early twentieth-century warming in the Arctic—A possible mechanism. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 4045–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, O.M.; Bengtsson, L.; Miles, M.W.; Kuzmina, S.I.; Semenov, V.A.; Alekseev, G.V.; Nagurnyi, A.P.; Zakharov, V.F.; Bobylev, L.P.; Pettersson, L.H.; et al. Arctic climate change: Observed and modelled temperature and sea-ice variability. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2004, 56, 328–341. [Google Scholar]

- Chylek, P.; Folland, C.K.; Lesins, G.; Dubey, M.K.; Wang, M. Arctic air temperature change amplification and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L14801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokuchava, D.D.; Semenov, V.A. Factors of natural climate variability contributing to the Early 20th Century Warming in the Arctic. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 606, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerl, G.C.; Brönnimann, S.; Cowan, T.; Friedman, A.R.; Hawkins, E.; Iles, C.; Müller, W.; Schurer, A.; Undorf, S. Causes of climate change over the historical record. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegerl, G.C.; Brönnimann, S.; Schurer, A.; Cowan, T. The early 20th century warming: Anomalies, causes, and consequences. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2018, 9, e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.R.; Overland, J.E. Early 20th century Arctic warming in retrospect. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 30, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, T. Early 20th century warming in the Arctic: A review. Polar Sci. 2011, 5, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokuchava, D.D.; Semenov, V.A. Mechanisms of the early 20th century warming in the Arctic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 222, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekryaev, R.V.; Polyakov, I.V.; Alexeev, V.A. Role of polar amplification in long-term surface air temperature variations and modern Arctic warming. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 3888–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.S. Concerning a Change of Climate During Recent Decades in the Arctic and Subarctic Regions: From Greenland in the West to Eurasia in the East, and Contemporary Biological and Geophysical Changes; E. Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlmann, H.W. Glaciological Research on the North Atlantic Coast; Royal Geographical Society Research Series; Royal Geographical Society: London, UK, 1948; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Semenov, V.A.; Latif, M. The early twentieth century warming and winter Arctic sea ice. Cryosphere 2012, 6, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, V.A.; Aldonina, T.A.; Li, F.; Keenlyside, N.S.; Wang, L. Arctic sea ice variations in the first half of the 20th century: A new reconstruction based on hydrometeorological data. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, L.; Otterå, O.H.; Bentsen, M.; Gao, Y.; Johannessen, O.M. External forcing of the early 20th century Arctic warming. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2013, 65, 20578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Ishii, M.; Oshima, N.; Yukimoto, S.; Hasumi, H. Arctic warming and associated sea ice reduction in the early 20th century induced by natural forcings in MRI-ESM2.0 climate simulations and multimodel analyses. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL092336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Oshima, N.; Yukimoto, S. Contributions of anthropogenic aerosol forcing and multidecadal internal variability to mid-20th century Arctic cooling—CMIP6/DAMIP multimodel analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dai, A. Quantifying contributions of external forcing and internal variability to Arctic warming during 1900–2021. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2023EF003734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latonin, M.M.; Bashmachnikov, I.L.; Bobylev, L.P.; Davy, R. Multi-model ensemble mean of global climate models fails to reproduce early twentieth century Arctic warming. Polar Sci. 2021, 30, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. The roles of external forcing and natural variability in global warming hiatuses. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 47, 3157–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Francis, J.; Hanna, E. The “warm-Arctic/cold-continents” pattern during 1901–2010. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 5245–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, M.; Jahn, A.; Polvani, L. Nonuniform contribution of internal variability to recent Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 4039–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Wang, J.; Beletsky, D.; Overland, J.; Ikeda, M.; Wan, L. Accelerated decline of summer Arctic sea ice during 1850–2017 and the amplified Arctic warming during the recent decades. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 034015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnston, A.G.; Livezey, R.E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 1987, 115, 1083–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 1995, 269, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.J.; Wallace, J.M. The Arctic Oscillation signature in the wintertime geopotential height and temperature fields. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Barlow, M. The NAO, the AO, and global warming: How closely related? J. Clim. 2005, 18, 4498–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, S.B. Fundamental mechanisms of the growth and decay of the PNA teleconnection pattern. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 128, 775–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.W.; Divine, D.V.; Furevik, T.; Jansen, E.; Moros, M.; Ogilvie, A.E. A signal of persistent Atlantic multidecadal variability in Arctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, O.M.; Kuzmina, S.I.; Bobylev, L.P.; Miles, M.W. Surface air temperature variability and trends in the Arctic: New amplification assessment and regionalisation. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2016, 68, 28234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, M.E.; Ramankutty, N. An oscillation in the global climate system of period 65–70 years. Nature 1994, 367, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Screen, J.A.; Francis, J.A. Contribution of sea-ice loss to Arctic amplification is regulated by Pacific Ocean decadal variability. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantua, N.J.; Hare, S.R. The Pacific decadal oscillation. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylek, P.; Klett, J.D.; Dubey, M.K.; Hengartner, N. The role of Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation in the global mean temperature variability. Clim. Dyn. 2016, 47, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, L.; Keenlyside, N.; Bethke, I.; Gao, Y.; Omrani, N.E. Pacific contribution to the early twentieth-century warming in the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, Y.; Xie, S.P. The tropical Pacific as a key pacemaker of the variable rates of global warming. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokinaga, H.; Xie, S.P.; Mukougawa, H. Early 20th-century Arctic warming intensified by Pacific and Atlantic multidecadal variability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6227–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, M.; Brönnimann, S.; Compo, G.P. Tropospheric circulation during the early twentieth century Arctic warming. Clim. Dyn. 2017, 48, 2405–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhong, S.; Winkler, J.A.; Zhou, M.; Lenschow, D.H.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q. Possible connections of the opposite trends in Arctic and Antarctic sea-ice cover. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Alexander, M. Atmospheric bridge, oceanic tunnel, and global climatic teleconnections. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruprich-Robert, Y.; Msadek, R.; Castruccio, F.; Yeager, S.; Delworth, T.; Danabasoglu, G. Assessing the climate impacts of the observed Atlantic multidecadal variability using the GFDL CM2. 1 and NCAR CESM1 global coupled models. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 2785–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Luo, D.; Dai, A.; Simmonds, I.; Wu, L. Decadal variability of winter warm Arctic-cold Eurasia dipole patterns modulated by Pacific decadal oscillation and Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Delworth, T.L. Impact of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation on North Pacific climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L23708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Stuecker, M.F.; Turner, A.G.; Jin, F.F.; Geng, X. Impact of ENSO longitudinal position on teleconnections to the NAO. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, B.B.; Dunstone, N.J.; Halloran, P.R.; Andrews, T.; Bellouin, N. Aerosols implicated as a prime driver of twentieth-century North Atlantic climate variability. Nature 2012, 484, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Karami, K.; Tilmes, S.; Moore, J.C. Changes in global teleconnection patterns under global warming and stratospheric aerosol intervention scenarios. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 5835–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterå, O.H.; Bentsen, M.; Drange, H.; Suo, L. External forcing as a metronome for Atlantic multidecadal variability. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, D.; Hu, A. Internally generated and externally forced multidecadal oceanic modes and their influence on the summer rainfall over East Asia. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 8299–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankignoul, C.; Gastineau, G.; Kwon, Y.O. Estimation of the SST response to anthropogenic and external forcing and its impact on the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and the Pacific decadal oscillation. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 9871–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.N.; Bellomo, K.; Cane, M.; Clement, A. The role of historical forcings in simulating the observed Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, C.P.; Kennedy, J.J.; Rayner, N.A.; Winn, J.P.; Hogan, E.; Killick, R.E.; Dunn, R.J.H.; Osborn, T.J.; Jones, P.D.; Simpson, I.R. An updated assessment of near-surface temperature change from 1850: The HadCRUT5 data set. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2019JD032361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, N.J.; Schmidt, G.A.; Hansen, J.E.; Menne, M.J.; Persin, A.; Ruedy, R.; Zyss, D. Improvements in the GISTEMP uncertainty model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 6307–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, R.; Muller, R.; Jacobsen, R.; Perlmutter, S.; Rosenfeld, A.; Wurtele, J.; Wickham, S.; Curry, J.; Groom, D.; Mosher, S. Berkeley Earth Temperature Averaging Process, Geoinfor. Geostat.: An Overview 1: 2. Geoinform. Geostat. Overv. 2013, 1, 20–100. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, R.; Ansell, T. A new globally complete monthly historical gridded mean sea level pressure dataset (HadSLP2): 1850–2004. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 5816–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.J.; Rayner, N.A.; Atkinson, C.P.; Killick, R.E. An ensemble data set of sea surface temperature change from 1850: The Met Office Hadley Centre HadSST. 4.0. 0.0 data set. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 7719–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ols, C.; Klesse, S.; Girardin, M.P.; Evans, M.E.; DeRose, R.J.; Trouet, V. Detrending climate data prior to climate–growth analyses in dendroecology: A common best practice? Dendrochronologia 2023, 79, 126094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E.; Long, S.R.; Peng, C.K. On the trend, detrending, and variability of nonlinear and nonstationary time series. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14889–14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, K.; Nyarko, B.K.; Klutse, N.A.B.; Ansah-Narh, T.; Damoah, R.; Koffi, H.A. Quantifying the Influence of Remote Climate Indices on Key Climate Variables in Northern Ghana: A Comprehensive Multivariate Approach. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasel, H.M.; Imteaz, M.A.; Mekanik, F. Multiple regression modelling approach for rainfall prediction using large-scale climate indices as potential predictors. Int. J. Water 2017, 11, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.E. Arctic climate change, variability, and extremes. In Arctic Hydrology, Permafrost and Ecosystems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deser, C.; Lehner, F.; Rodgers, K.B.; Ault, T.; Delworth, T.L.; DiNezio, P.N.; Fiore, A.; Frankignoul, C.; Fyfe, G.C.; Horton, D.E.; et al. Insights from Earth system model initial-condition large ensembles and future prospects. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Woollings, T.; Sparrow, S.N.; Watson, P.A.; Screen, J.A. Response of winter climate and extreme weather to projected Arctic sea-ice loss in very large-ensemble climate model simulations. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Leung, L.R.; Lu, J.; Rasch, P.J.; Fu, Q.; Kravitz, B.; Zou, Y.; Cassano, J.J.; et al. The role of interdecadal climate oscillations in driving Arctic atmospheric river trends. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Predictor | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HadCRUT5-detrended | |||||

| PNA | 0.0 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 10.4 |

| NAO | 0.0 | 7.3 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 22.2 |

| PDO | 1.0 | 8.3 | 11.6 | 15.1 | 25.3 |

| AMO | 23.7 | 35.2 | 39.0 | 42.9 | 54.4 |

| R2 | 54.9 | 62.9 | 65.5 | 68.3 | 76.3 |

| HadCRUT5-CMIP6 | |||||

| PNA | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| NAO | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 3.3 |

| PDO | 11.1 | 22.1 | 25.7 | 29.5 | 40.5 |

| AMO | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 6.3 |

| R2 | 15.0 | 25.9 | 29.6 | 33.2 | 44.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bokuchava, D.D.; Semenov, V.A.; Aldonina, T.A.; Akperov, M.; Shtol, E.Y. Contribution of Leading Natural Climate Variability Modes to Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic in the Early 20th Century. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121391

Bokuchava DD, Semenov VA, Aldonina TA, Akperov M, Shtol EY. Contribution of Leading Natural Climate Variability Modes to Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic in the Early 20th Century. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121391

Chicago/Turabian StyleBokuchava, Daria D., Vladimir A. Semenov, Tatiana A. Aldonina, Mirseid Akperov, and Ekaterina Y. Shtol. 2025. "Contribution of Leading Natural Climate Variability Modes to Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic in the Early 20th Century" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121391

APA StyleBokuchava, D. D., Semenov, V. A., Aldonina, T. A., Akperov, M., & Shtol, E. Y. (2025). Contribution of Leading Natural Climate Variability Modes to Winter SAT Changes in the Arctic in the Early 20th Century. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121391