Contrasting Low-Latitude Ionospheric Total Electron Content Responses to the 7–8 and 10–11 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

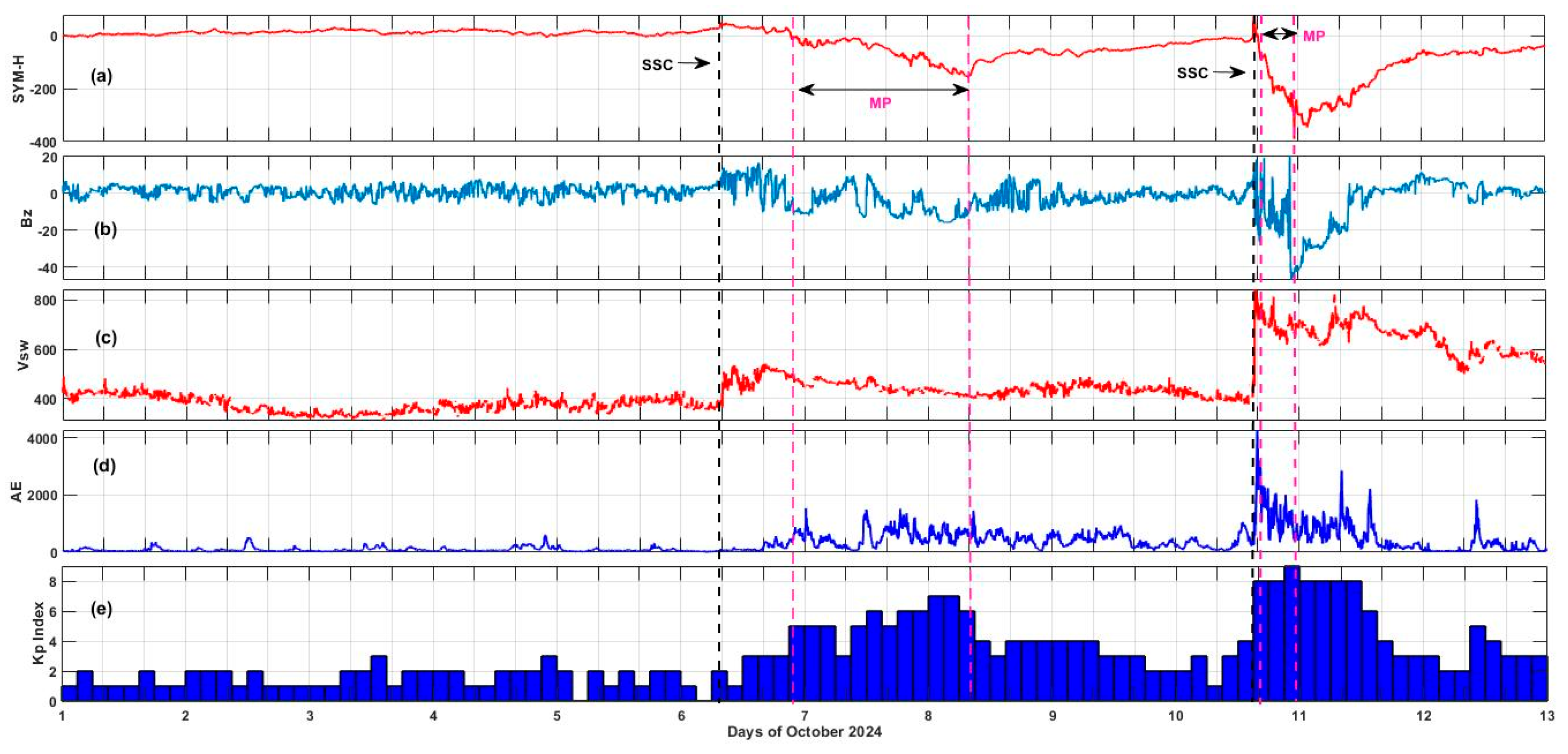

3.1. Solar and Geomagnetic Conditions During Two Storms

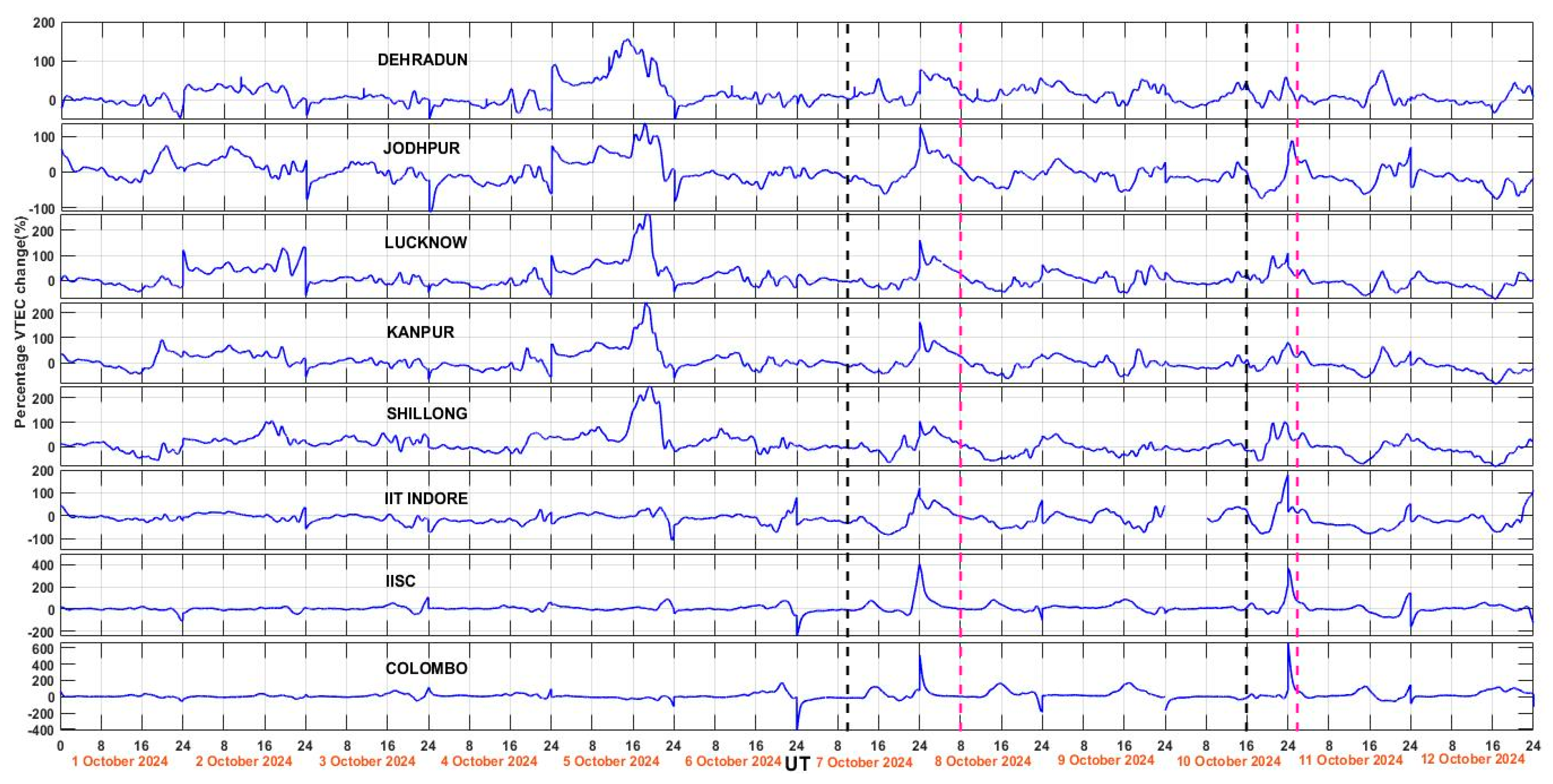

3.2. VTEC Variation During Two Storms

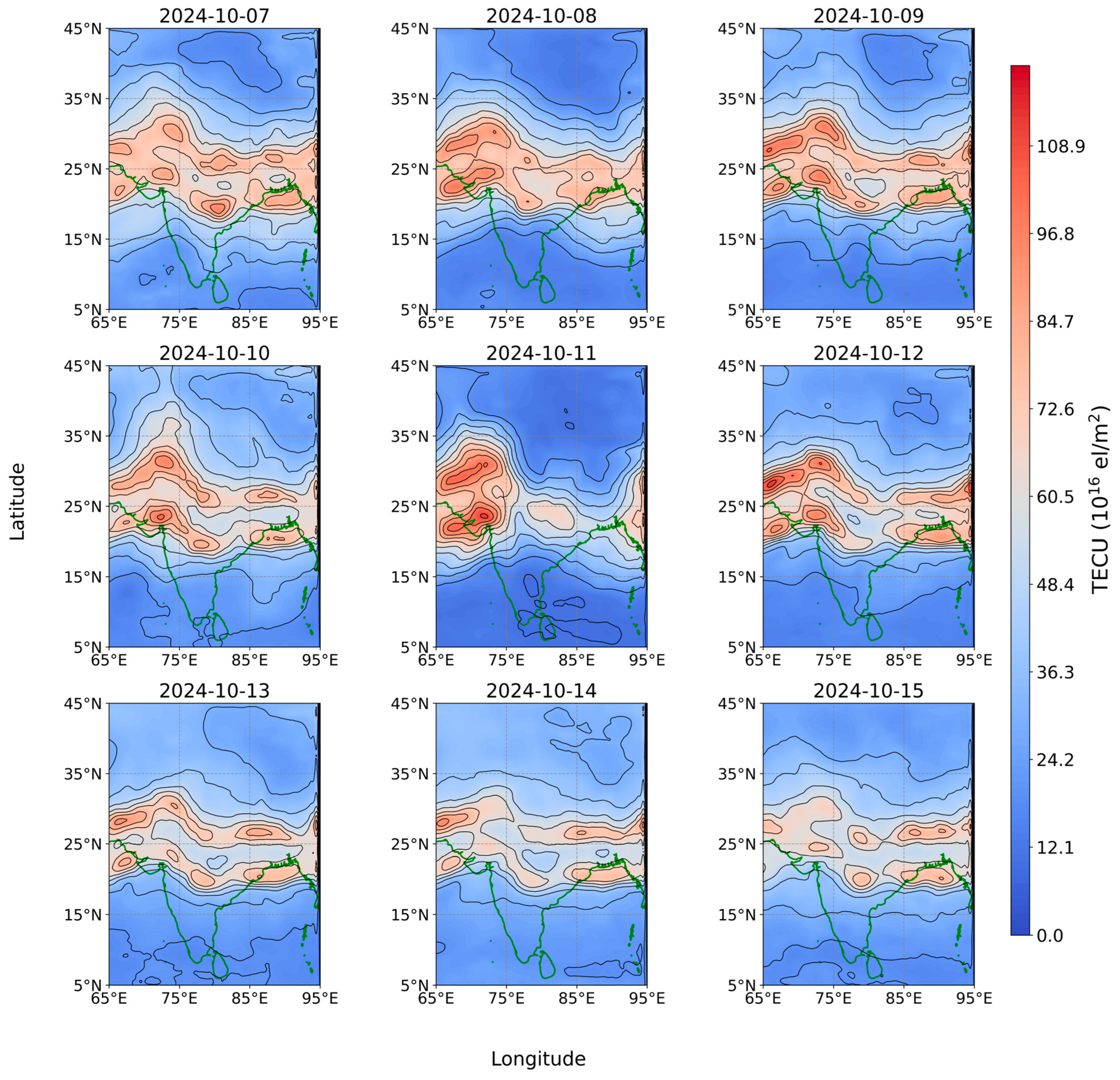

3.3. GIM-Derived VTEC Variation During the Two Storms

4. Discussion

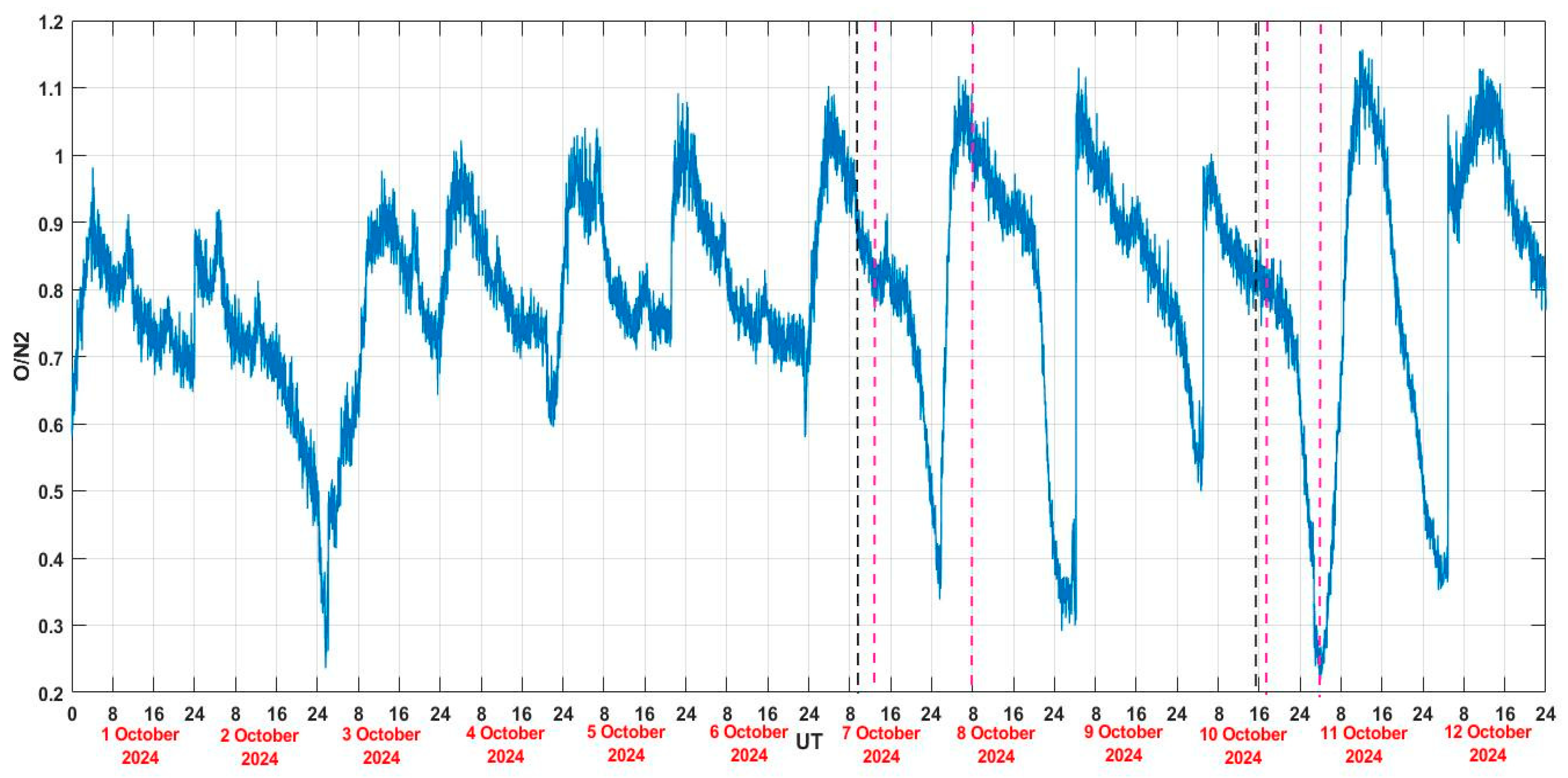

- The O/N2 ratio change during two storms

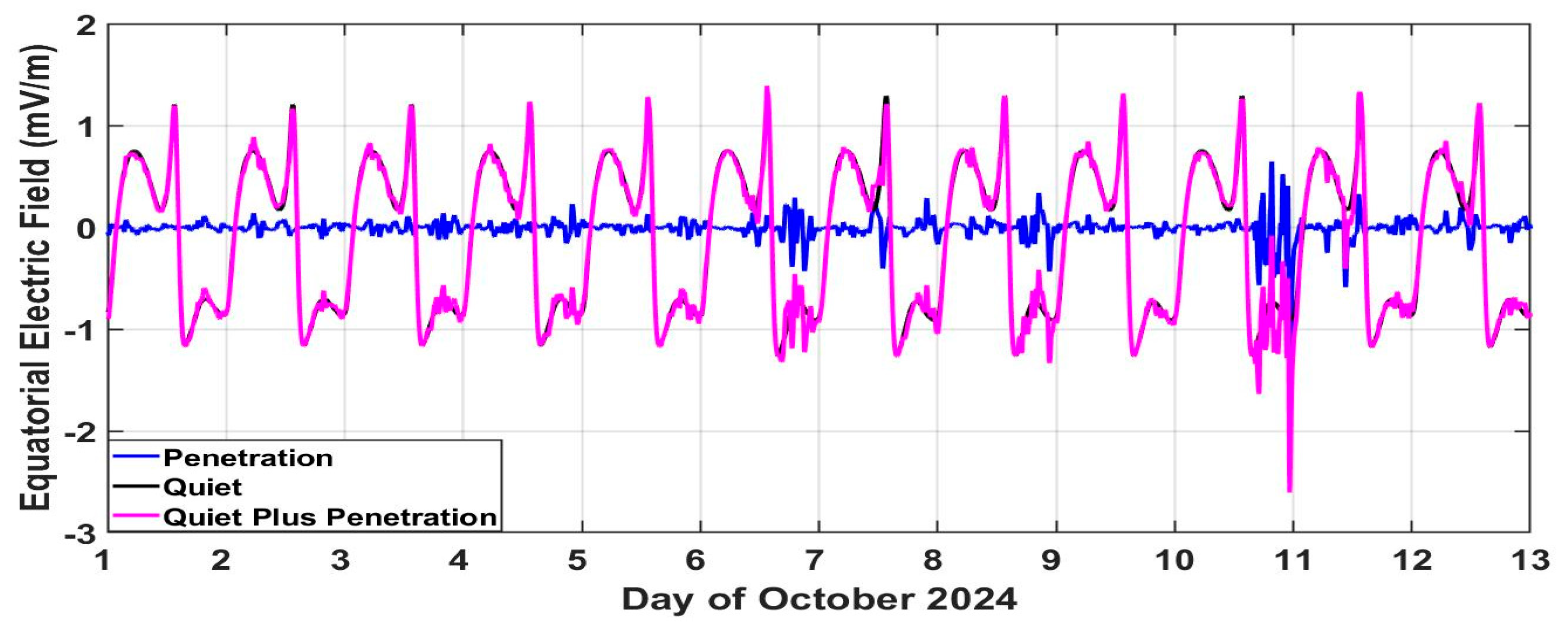

- The PPEF changes during two storms

- The DDEF change during two storms

- The EEJ variation during two storms

5. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| TEC | Total Electron Content |

| PPEF | prompt penetration electric field |

| DDEF | disturbance dynamo electric field |

References

- Tsurutani, B.T.; Gonzalez, W.D. The Interplanetary Causes of Magnetic Storms: A Review. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 1997, 98, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tsurutani, B.T.; Gonzalez, W.D.; Gonzalez, A.L.C.; Guarnieri, F.L.; Gopalswamy, N.; Grande, M.; Kamide, Y.; Kasahara, Y.; Lu, G.; Mann, I.; et al. Corotating Solar Wind Streams and Recurrent Geomagnetic Activity: A Review. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, A07S01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, W.D.; Joselyn, J.A.; Kamide, Y.; Kroehl, H.W.; Rostoker, G.; Tsurutani, B.T.; Vasyliūnas, V.M. What Is a Geomagnetic Storm? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1994, 99, 5771–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagouri, I. Space Weather Effects on the Earth’s Upper Atmosphere: Short Report on Ionospheric Storm Effects at Middle Latitudes. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermolaev, Y.I.; Yermolaev, M.Y. Solar and Interplanetary Sources of Geomagnetic Storms: Space weather aspects. lzv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2010, 46, 799–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.G.; Cane, H.V. Solar Wind Drivers of Geomagnetic Storms during More than Four Solar Cycles. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2012, 2, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeja, V.; Devasia, C.V.; Ravindran, S.; Pant, T.K.; Sridharan, R. Response of the equatorial and low-latitude ionosphere in the Indian sector to the geomagnetic storms of January 2005. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2009, 114, A06314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurutani, B.T.; Mannucci, A.J.; Iijima, B.A.; Guarnieri, F.L.; Gonzalez, W.D.; Judge, D.L.; Wu, S.T.; Tsuda, T.; Saito, A. Global Dayside Ionospheric Uplift and Enhancement Associated with Interplanetary Electric Fields. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, A08302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C. Storm-time plasma transport at middle and high latitudes. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharenko, L.P.; Coster, A.J.; Chau, J.L.; Valladares, C.E. Impact of Sudden Stratospheric Warmings on Equatorial Ionization Anomaly. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2007, 112, A10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, A.J.; Wilson, B.D.; Yuan, D.N.; Ho, C.H.; Lindqwister, U.J.; Runge, T.F. A global mapping technique for GPS-derived ionospheric total electron content measurements. Radio Sci. 1998, 33, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pajares, M.; Juan, J.M.; Sanz, J.; Orus, R.; Garcia-Rigo, A.; Feltens, J.; Komjathy, A.; Schaer, S.C.; Krankowski, A. The IGS VTEC maps: A reliable source of ionospheric information since 1998. J. Geod. 2009, 83, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.C. The Earth’s Ionosphere: Plasma Physics and Electrodynamics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S.; Basu, S.; Valladares, C.E.; Yeh, H.; Su, S.; MacKenzie, E.; Sultan, P.J.; Aarons, J.; Rich, F.J.; Doherty, P.; et al. Ionospheric effects of major magnetic storms during the International Space Weather Period of September and October 1999: GPS observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 30389–30413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Chu, Y.H.; Lee, C.; Cheng, C.Z.; Liu, J.Y. Ionospheric Dynamics and Irregularities Following the 30 October 2003 Solar Flare and Geomagnetic Storm Event. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2005, 110, A09S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Sarkar, S.; Nanda, K.; Sanyal, A.; Brawar, B.; Datta, A.; Potirakis, S.M.; Maurya, A.K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Panchadhyayee, P.; et al. Global Response of Vertical Total Electron Content to Mother’s Day G5 Geomagnetic Storm of May 2024: Insights from IGS and GIM Observations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, D.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Patra, S.; Karan, D.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Scipión, D.; Chakrabarty, D.; Riccobono, J. Evidence of Unusually Strong Equatorial Ionization Anomaly at Three Local Time Sectors during the Mother’s Day Geomagnetic Storm on 10–11 May 2024. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 52, e2024GL111269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Scipión, D.E.; Kuyeng, K.; Condor, P.; De La Jara, C.; Velasquez, J.P.; Flores, R.; Ivan, E. Ionospheric Disturbances Observed over the Peruvian Sector during the Mother’s Day Storm (G5-Level) on 10–12 May 2024. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2024, 129, e2024JA033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.D.; Barbier, H.; Carvajal, W.; Guamán, L. Ionospheric Response to the May 11, 2024, Geomagnetic Superstorm over Ecuador. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, I.; Thampi, S.V.; Bhaskar, A. Electrodynamic Forcing of the Duskside Ionosphere and the Super-Fountain Effect during the Superstorm of May 10 to 11 2024. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojilova, R.; Mukhtarov, P.; Pancheva, D. Global ionospheric response during extreme geomagnetic storm in May 2024. Remote Sens. 2025, 16, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.C.; Erickson, P.J.; Nishimura, Y.; Zhang, S.R.; Bush, D.C.; Coster, A.J.; Meade, P.E.; Franco-Diaz, E. Imaging the May 2024 extreme aurora with ionospheric total electron content. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL111981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Malik, S.K.; Satyam, S.; Reddy, B.M.; Rathore, B.P.; Godbole, R. Extreme Low-Latitude Ionospheric Disturbances during the 10–11 May 2024 Geomagnetic Superstorm. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 75, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, C.S.; Dai, L.; Wrasse, C.M.; Barros, D.; Takahashi, H.; Figueiredo, C.A.O.B.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Ionospheric response to the extreme 2024 “Mother’s Day” geomagnetic storm over the Latin American sector. Space Weather 2024, 22, e2024SW004054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.S.; Haralambous, H.; Moses, M.; Tripathi, S.C. Effects of the October 2024 Storm over the Global Ionosphere. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picanço, G.A.S.; Fagundes, P.R.; Moro, J.; Nogueira, P.A.B.; Muella, M.T.A.H.; Denardini, C.M.; Resende, L.C.A.; da Silva, L.A.; Laranja, S.R. Dynamics of Polar-Equatorial Ionospheric Irregularities During the 10-13 October 2024 Superstorm. ESS Open Archive 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Scipión, D.E.; Kuyeng, K.; Condor, P.; Flores, R.; Pacheco, E.; De La Jara, C.; Manay, E. Ionospheric responses to an extreme (G5-level) geomagnetic storm using multi-instrument measurements at the Jicamarca Radio Observatory on 10–11 October 2024. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2025, 130, e2024JA033642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K. Correlation Study of Auroral Currents with External Parameters During 10–12 October 2024 Superstorm. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.C.; Haralambous, H.; Biswas, T. Ionospheric Variability During the 10 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storm: A Regional Analysis across Europe. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrard, V.; Verhulst, T.G.W.; Chevalier, J.-M.; Bergeot, N.; Winant, A. Effects of the Geomagnetic Superstorms of 10–11 May 2024 and 7–11 October 2024 on the Ionosphere and Plasmasphere. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aa, E.; Zhang, S.; Coster, A.J.; Hairston, M.R.; Kerr, R.B.; Souza, J.R.; Cai, X.; Luo, B. Super equatorial plasmabubbles and strong longitudinal variabilityduring the 10–11 October 2024geomagnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2025, 130, e2025JA034224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharenkova, I.; Cherniak, I.; Krankowski, A.; Valladares, C.E.; De la Jara Sanchez, C. On detection of super equatorial plasma bubbles in the American sector during the 10–11 October 2024 geomagnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2025, 130, e2025JA033709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, S. Mapping and Predicting the Earth’s Ionosphere Using the Global Positioning System. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Hernández-Pajares, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, N.; Yuan, H. Integrity investigation of global ionospheric TEC maps for high-precision positioning. J. Geod. 2021, 95, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Ionospheric Electron Enhancement Preceding the 2011 Tohoku-Oki Earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Jin, R.; Feng, G. GNSS Ionospheric Seismology: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 147, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama Rao, P.V.S.; Gopi Krishna, S.; Niranjan, K.; Prasad, D.S.V.V.D. Temporal and Spatial Variations in TEC Using Simultaneous Measurements from the Indian GPS Network of Receivers during the Geomagnetic Storm of July 2004. Ann. Geophys. 2006, 24, 3279–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. GPS derived ionospheric TEC response to geomagnetic storm on 24 August 2005 at Indian low latitude stations. Adv. Space Res. 2011, 47, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, B.; Rodríguez-Zuluaga, J.; Alazo-Cuartas, K.; Kashcheyev, A.; Migoya-Orué, Y.; Radicella, S.M.; Zakharenkova, I. Middle- and Low-Latitude Ionosphere Response to the 2015 St. Patrick’s Day Geomagnetic Storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2016, 121, 3421–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagiya, M.S.; Iyer, K.N.; Joshi, H.P.; Thampi, S.V.; Tsugawa, T.; Ravindran, S.; Sridharan, R.; Pathan, B.M. Low-latitude ionospheric-thermospheric response to storm time electrodynamical coupling between high and low latitudes. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, A01303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebiyi, S.J.; Adimula, I.A.; Oladipo, O.A. Investigation on mid-latitude stations to storm-time variations of GPS-TEC. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 55, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S. Equatorial ionization anomaly and ionospheric responses to geomagnetic storms: Case studies over Indian longitude sector. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 56, 1713–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Rowell, T.J.; Codrescu, M.V.; Roble, R.G.; Richmond, A.D. How does the thermosphere and ionosphere react to ageomagnetic storm? Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 1997, 98, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendillo, M. Storms in the Ionosphere: Patterns and Processes for Total Electron Content. Rev. Geophys. 2006, 44, RG4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.G.; Killeen, T.L.; Roble, R.G. Large enhancements in the O/N2 ratio in the evening sector of the winter hemisphere during geomagnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1991, 96, 14377–14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.D.; Lu, G. Upper-Atmospheric Effects of Magnetic Storms: A Brief Tutorial. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2000, 62, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, N.; Batista, I.S.; Abdu, M.A.; Souza, J.R.; Bailey, G.J.; Su, Y.Z. Physical mechanism and statistics of positive ionospheric storms in the low latitude ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2010, 115, A04303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, C.; Maus, S. A Real-Time Forecast Service for the Ionospheric Equatorial Zonal Electric Field. Space Weather 2012, 10, S09002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejer, B.G.; Jensen, J.W.; Su, S.-Y. Quiet time equatorial F region vertical plasma drift model derived from ROCSAT-1 observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2008, 113, A05304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S. Penetration Electric Fields: Observations and Theory. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2018, 171, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, M.V.; Klimenko, V.V. Disturbance dynamo, prompt penetration electric field and overshielding in the Earth’s ionosphere during geomagnetic storm. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2012, 90–91, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, N.; Richmond, A.D.; Fuller-Rowell, T.J.; Codrescu, M.V.; Sazykin, S.; Toffoletto, F.R.; Spiro, R.W.; Millward, G.H. Interaction between direct penetration and disturbance dynamo electric fields in the storm-time equatorial ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejer, B.G.; Scherliess, L. Empirical models of storm time equatorial zonal electric fields. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1997, 102, 24047–24056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-S. Identification ofpenetration and disturbance dynamoelectric fields and their effects on thegeneration of equatorial plasma bubbles. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2023, 128, e2023JA031766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.G. Critical problems of equatorial electrojet. Adv. Space Res. 1992, 12, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, N.; Arora, K.; Nagarajan, N. A comparison of equatorial electrojet indices derived using magnetic field data from the Indian sector. Earth Planets Space 2014, 66, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Maute, A. Sq and EEJ—A review on the daily variation of the geomagnetic field caused by ionospheric dynamo currents. Space Sci. Rev. 2017, 206, 299–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Hashimoto, K.K.; Nozaki, K. Penetration of Magnetospheric Electric Fields to the Equator during a Geomagnetic Storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2000, 105, 23151–23162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.A.; Batista, P.P.; Batista, P.P.; Brum, C.G.M.; Carrasco, A.J.; Reinisch, B.W. Planetary wave oscillations in mesospheric winds, equatorial eveningprereversal electric field and spread F. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 33, L07107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M.; Richmond, A.D. The ionospheric disturbance dynamo. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1980, 85, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D.; Sekar, R.; Narayanan, R.; Sripathi, S. Impact of prompt penetration electric fields and disturbance dynamo electric fields on the equatorial electrojet. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2012, 117, A10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.P. Global evolution of F2-region storms. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1973, 35, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No. | GNSS Station Code | GNSS Station Location | Geographic Latitude | Geographic Longitude | Geomagnetic Latitude | Geomagnetic Longitude | GNSS Network Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | JDPR00IND | Jodhpur | 26.20 N | 73.02 E | 18.31 N | 147.84 E | IGS |

| 2 | DRDN00IND | Dehradun | 30.34 N | 78.04 E | 22.01 N | 152.90 E | IGS |

| 3 | IITK00IND | Kanpur | 26.52 N | 80.23 E | 18.06 N | 154.65 E | IGS |

| 4 | LCK400IND | Lucknow | 26.91 N | 80.95 E | 18.40 N | 155.36 E | IGS |

| 5 | SHLG00IND | Shillong | 25.67 N | 91.91 E | 16.58 N | 165.57 E | IGS |

| 6 | IIT INDR | Indore | 22.52 N | 75.92 E | 14.42 N | 150.24 E | Local |

| 7 | IISC00IND | Bangalore | 13.02 N | 77.57 E | 04.87 N | 151.03 E | IGS |

| 8 | SGOC00LKA | Sri Lanka | 06.89 N | 79.87 E | 01.38 S | 152.82 E | IGS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhattacharjee, S.; Shrivastava, M.N.; Pandey, U.; Brawar, B.; Nanda, K.; Panda, S.K.; Potirakis, S.M.; Sasmal, S.; Datta, A.; Maurya, A.K. Contrasting Low-Latitude Ionospheric Total Electron Content Responses to the 7–8 and 10–11 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storms. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121364

Bhattacharjee S, Shrivastava MN, Pandey U, Brawar B, Nanda K, Panda SK, Potirakis SM, Sasmal S, Datta A, Maurya AK. Contrasting Low-Latitude Ionospheric Total Electron Content Responses to the 7–8 and 10–11 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storms. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121364

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhattacharjee, Srijani, Mahesh N. Shrivastava, Uma Pandey, Bhuvnesh Brawar, Kousik Nanda, Sampad Kumar Panda, Stelios M. Potirakis, Sudipta Sasmal, Abhirup Datta, and Ajeet K. Maurya. 2025. "Contrasting Low-Latitude Ionospheric Total Electron Content Responses to the 7–8 and 10–11 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storms" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121364

APA StyleBhattacharjee, S., Shrivastava, M. N., Pandey, U., Brawar, B., Nanda, K., Panda, S. K., Potirakis, S. M., Sasmal, S., Datta, A., & Maurya, A. K. (2025). Contrasting Low-Latitude Ionospheric Total Electron Content Responses to the 7–8 and 10–11 October 2024 Geomagnetic Storms. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121364