Long-Term Trends and Seasonally Resolved Drivers of Surface Albedo Across China Using GTWR

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Albedo Data

2.2.2. Vegetation Data

2.2.3. Climate Data

2.3. Data Uncertainty and Consistency Assessment

2.3.1. Dataset Composition and Preprocessing

2.3.2. Uncertainty Analysis and Robustness Testing

2.3.3. Discussion on Time Consistency

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Albedo Calculation

2.4.2. Trend Analysis

2.4.3. Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression

3. Results

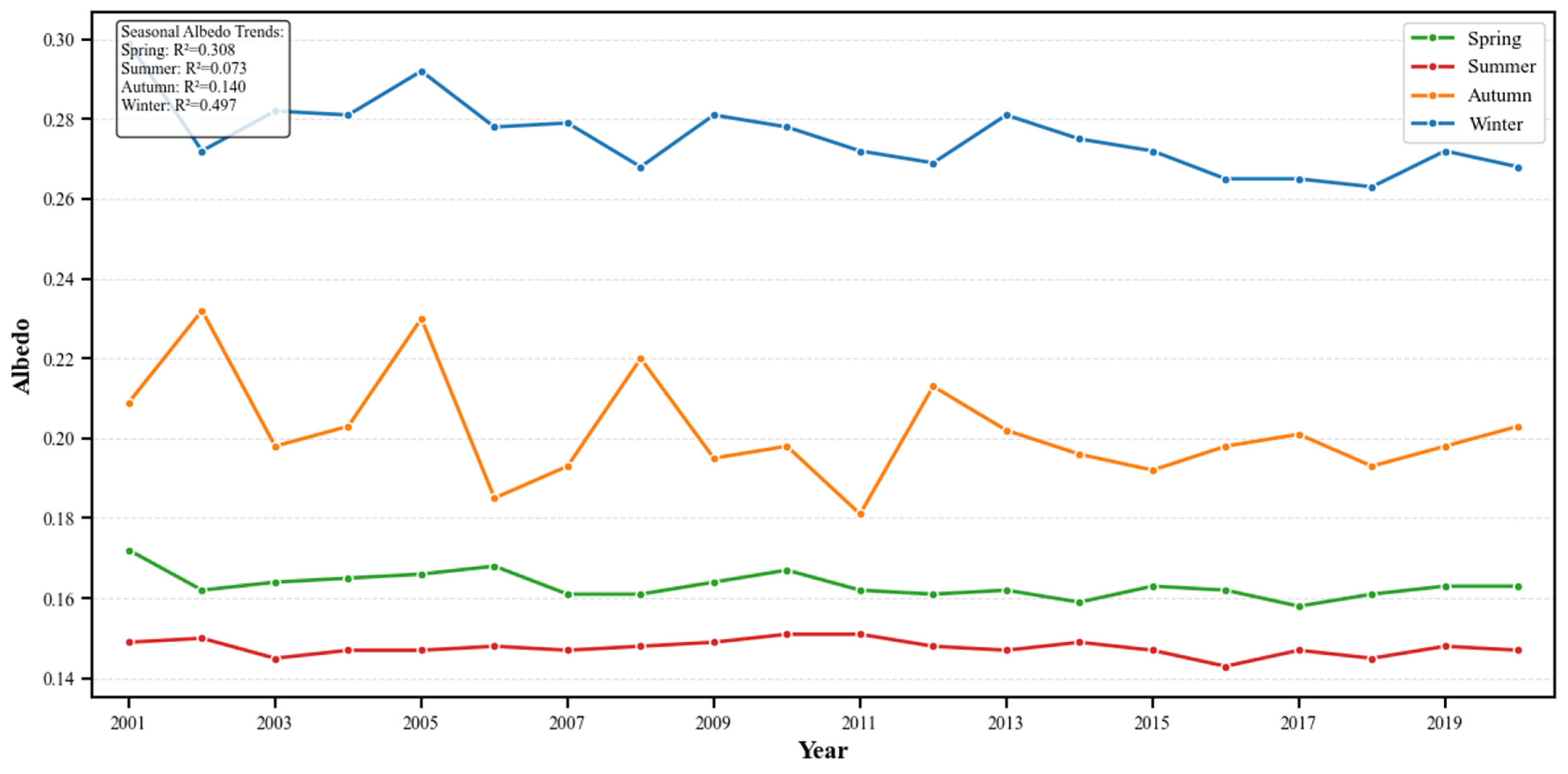

3.1. Interannual Variation of Surface Albedo

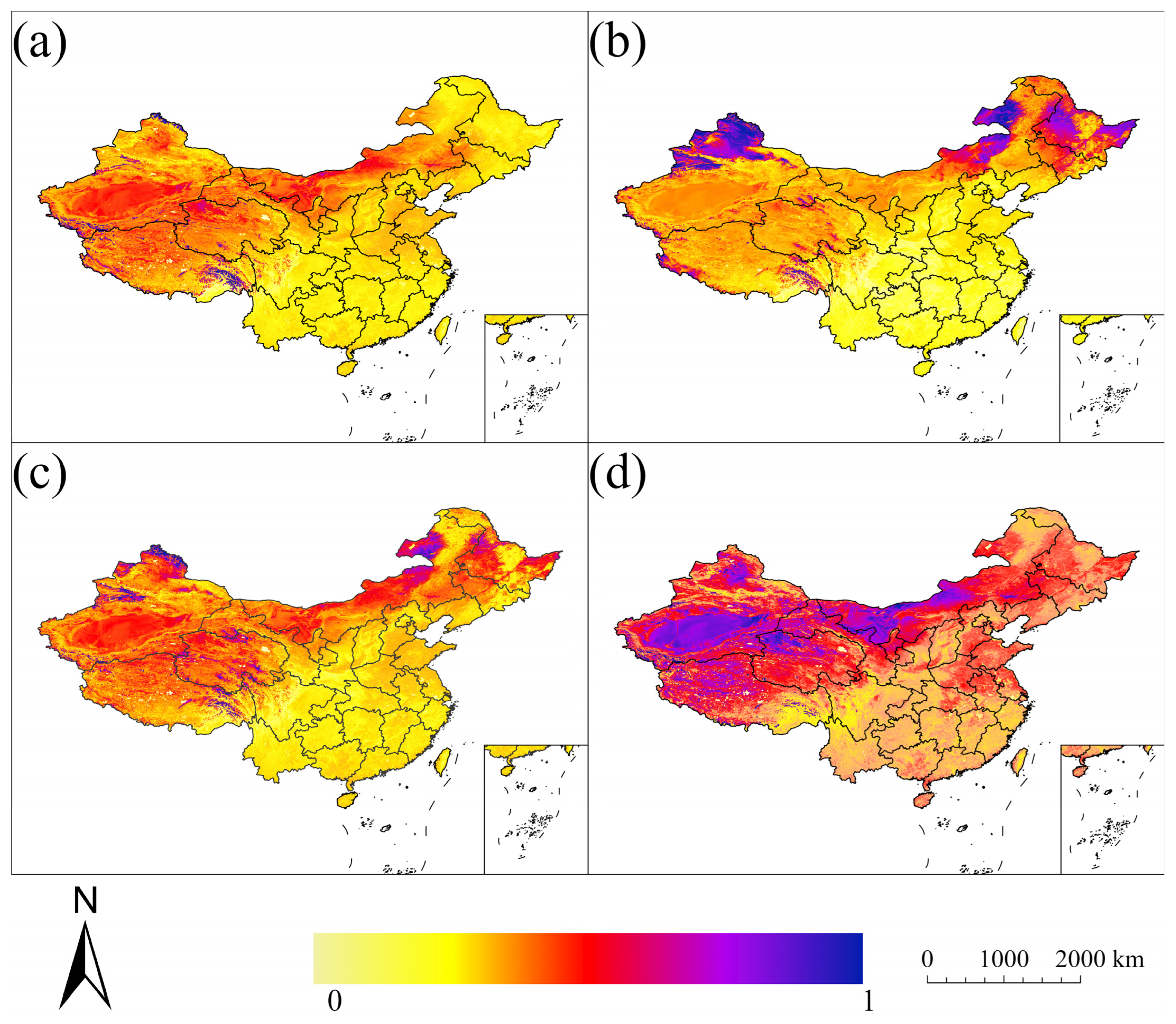

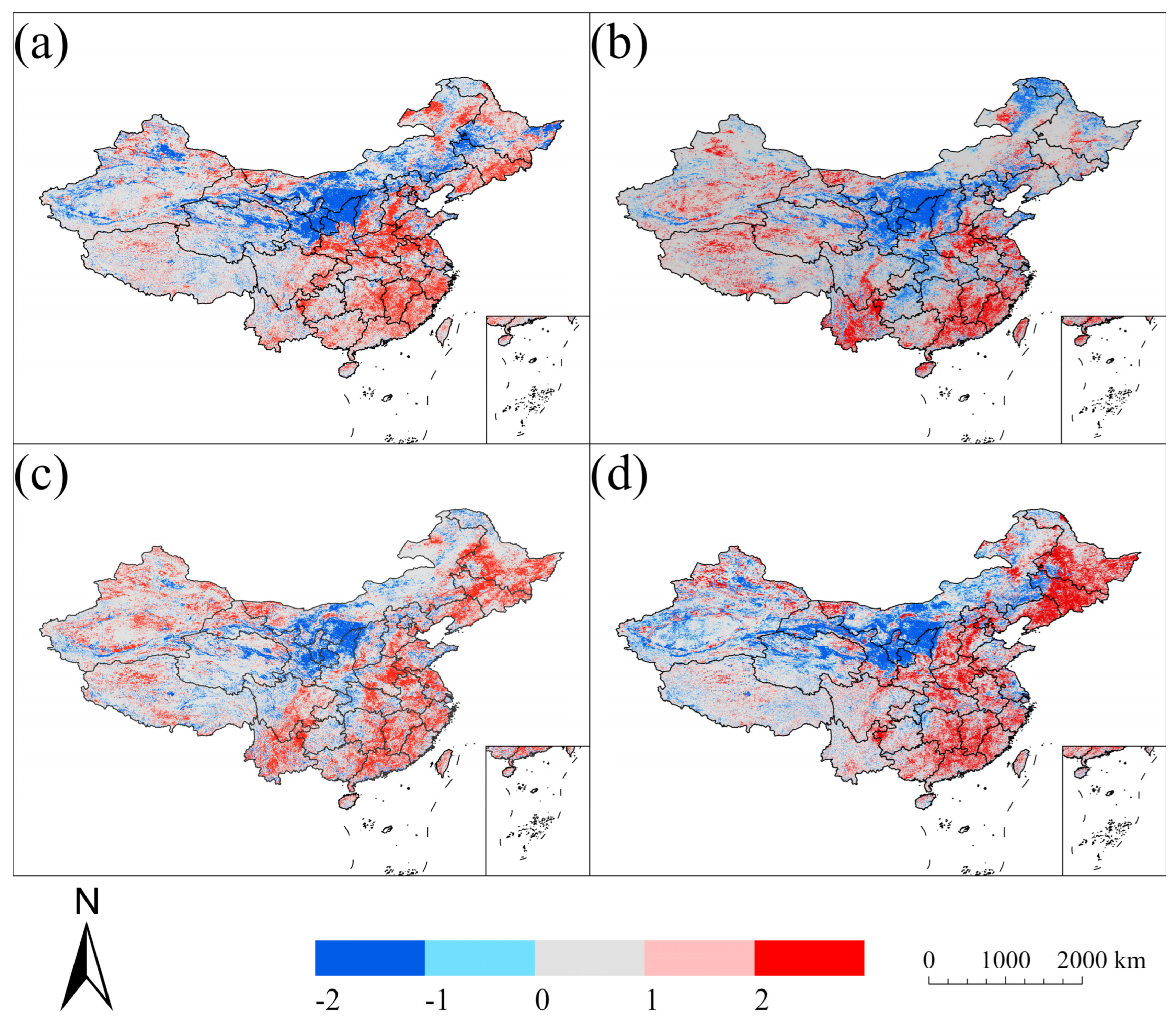

3.2. Seasonal Dynamics of Surface Albedo

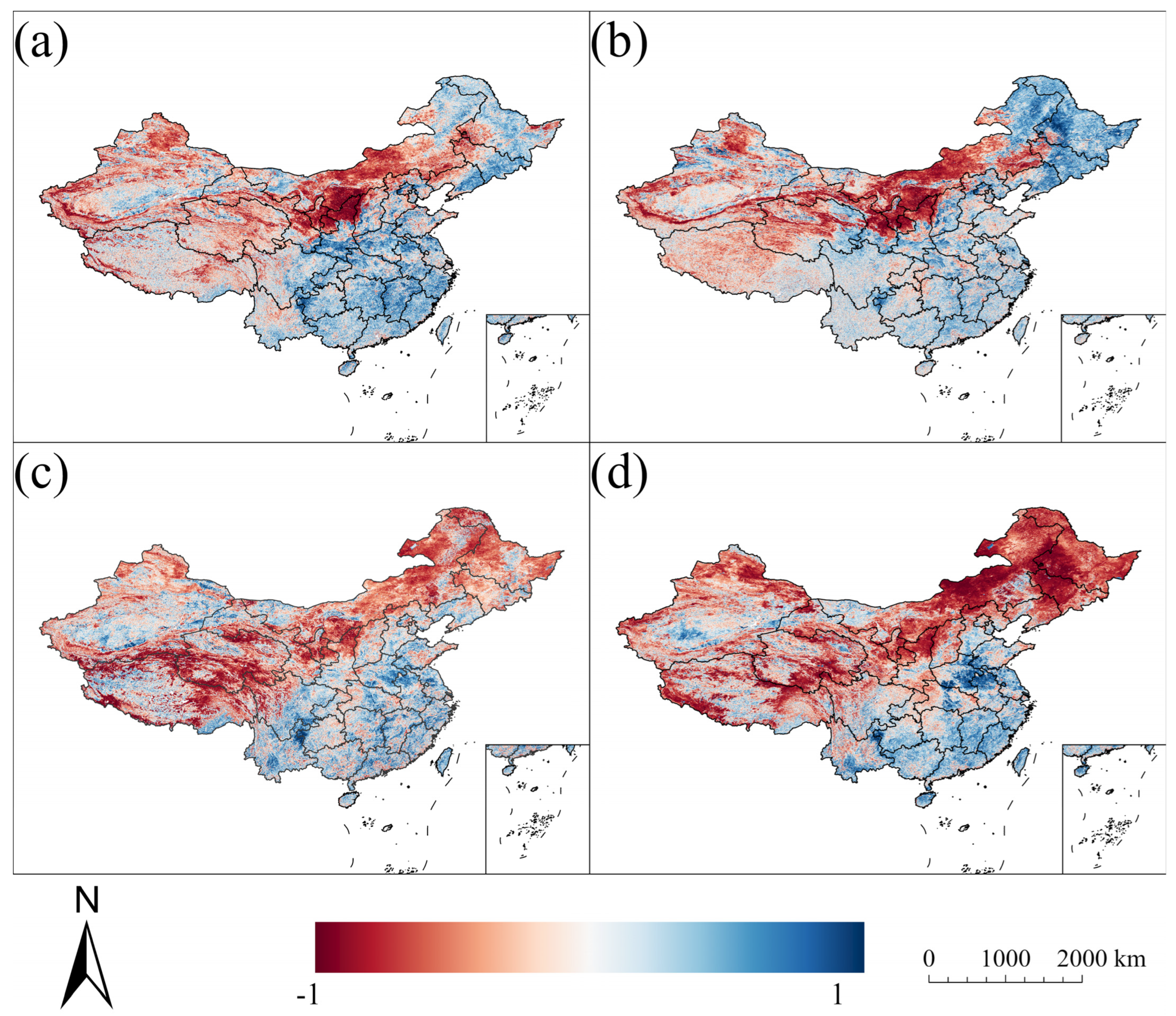

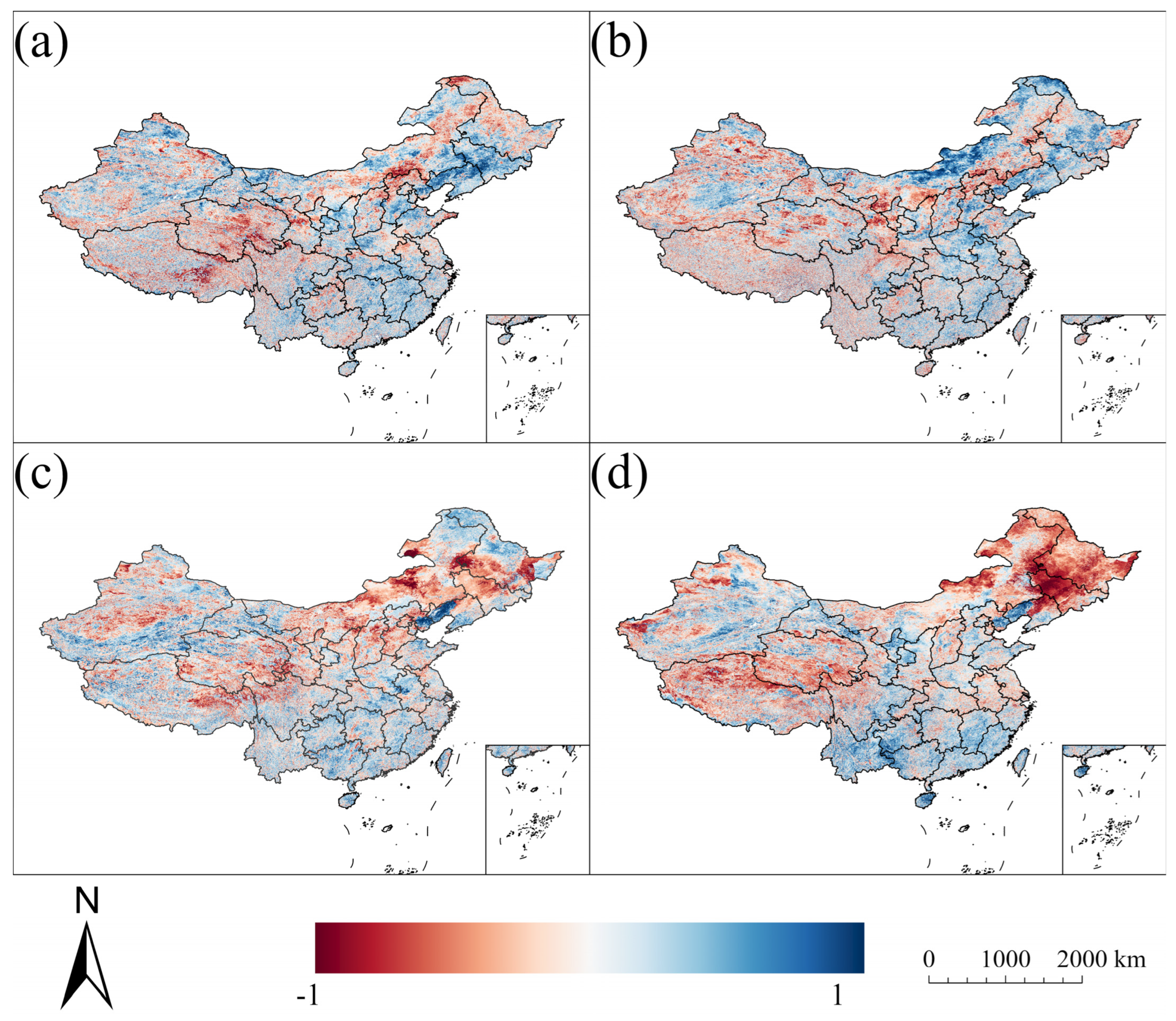

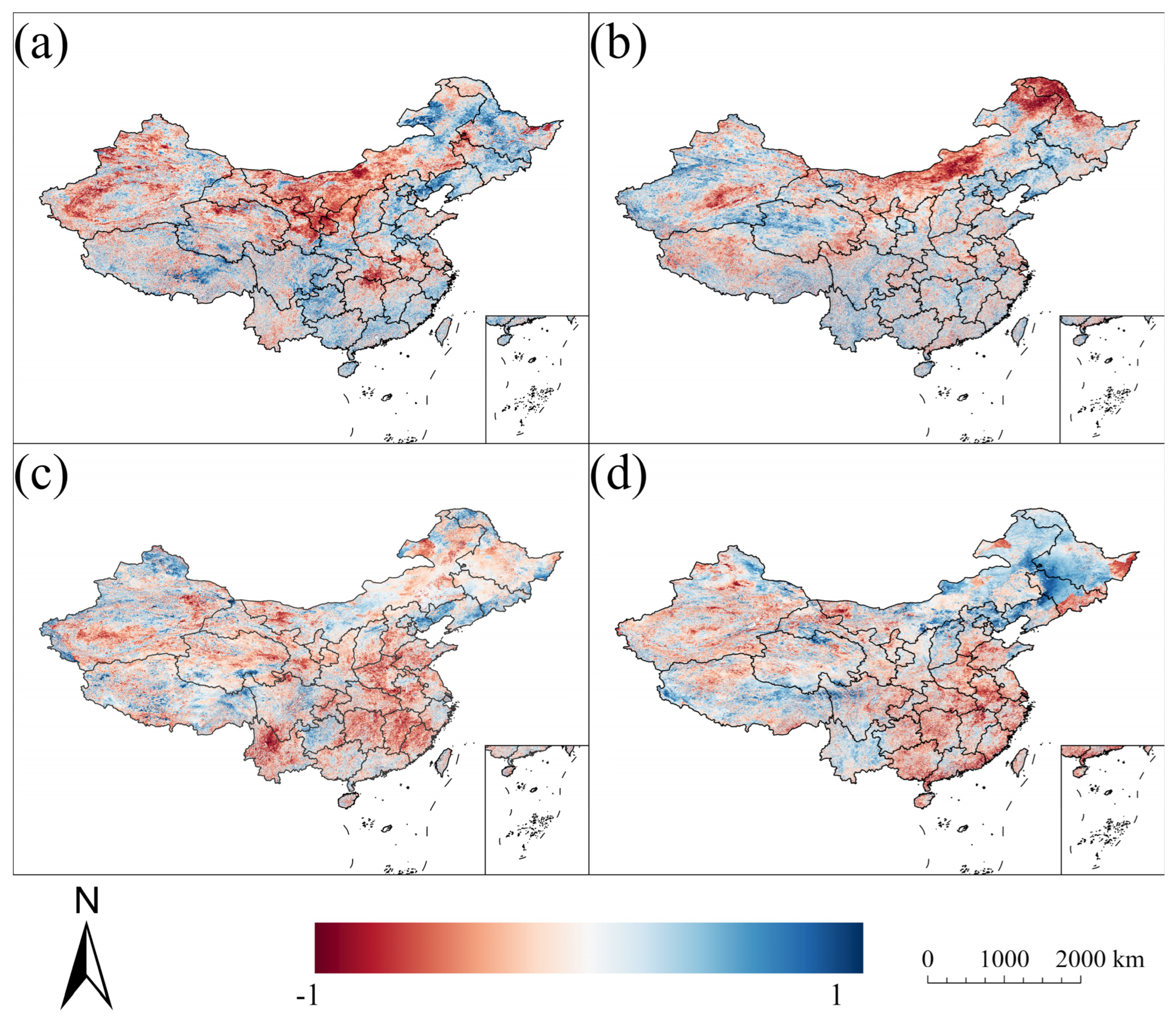

3.3. Relationships Between Albedo and NDVI/Temperature/Precipitation

3.4. Contribution of Each Factor

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Dynamics of Albedo and Key Influences

4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity Across Regions

4.3. Suggestions and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Bach, E. A Global Assessment of the Effects of Solar Farms on Albedo, Vegetation, and Land Surface Temperature Using Remote Sensing. Sol. Energy 2024, 268, 112198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, N.; Williams, C.A.; Denney, V.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Shrestha, S.; Terasaki Hart, D.E.; Wolff, N.H.; Yeo, S.; Crowther, T.W.; Werden, L.K.; et al. Accounting for Albedo Change to Identify Climate-Positive Tree Cover Restoration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Sciusco, P.; Jiao, T.; Feron, S.; Lei, C.; Li, F.; John, R.; Fan, P.; Li, X.; Williams, C.A.; et al. Albedo Changes Caused by Future Urbanization Contribute to Global Warming. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cabeza, V.P.; Alzate-Gaviria, S.; Diz-Mellado, E.; Rivera-Gomez, C.; Galan-Marin, C. Albedo Influence on the Microclimate and Thermal Comfort of Courtyards under Mediterranean Hot Summer Climate Conditions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Chen, J.; Ibáñez, I.; Sciusco, P.; Shirkey, G.; Lei, M.; Reich, P.; Robertson, G.P. Albedo of Crops as a Nature-Based Climate Solution to Global Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 084032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Kang, S.; Shangguan, D.; Luo, X. Albedo Reduction as an Important Driver for Glacier Melting in Tibetan Plateau and Its Surrounding Areas. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 220, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Schaaf, C.B.; Sun, Q.; Shuai, Y.; Román, M.O. Capturing Rapid Land Surface Dynamics with Collection V006 MODIS BRDF/NBAR/Albedo (MCD43) Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 207, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscas, D.; Bonciarelli, L.; Filipponi, M.; Orlandi, F.; Fornaciari, M. Urban Tree CO2 Compensation by Albedo. Land 2025, 14, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Wang, L.; Gueymard, C.A.; Bilal, M.; Lin, A.; Wei, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X. Constructing a Gridded Direct Normal Irradiance Dataset in China during 1981–2014. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gong, J.; Luo, F.; Pan, Y. Effectiveness and Driving Mechanism of Ecological Restoration Efforts in China from 2009 to 2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 910, 168676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Liang, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, S. Estimating Arctic Sea-Ice Shortwave Albedo from MODIS Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 186, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Shu, M.; Ma, C.; Che, T. Evaluation of Surface Albedo Products from ERA5, JRA-55, MERRA-2, and CERES-EBAF on the Tibetan Plateau: Insights from in-Situ Observations and MODIS Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2547288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Liang, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, D.; Gao, F.; Liu, Q. Greenland Surface Albedo Changes in July 1981–2012 from Satellite Observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 044043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Freychet, N.; Tett, S. Homogenized Daily Relative Humidity Series in China during 1960–2017. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 37, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qiu, X.; Li, S.; Shi, G.; He, Y. Analysis of Surface Albedo over China Based on MODIS. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, K.; Xu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Cui, J.; Hong, Z. Spatial–Temporal Changes of Surface Albedo and Its Relationship with Climate Factors in the Source of Three Rivers Region. Arid Zone Res. 2014, 31, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tu, G.; Dong, W. The Variation Characteristics of Surface Albedo of Different Underlying Surface in Semi-Arid Region. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Cao, X.; Han, C.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bian, L. Spatial–Temporal Distribution and Variation of Land Surface Albedo over the Tibetan Plateau during 2000–2016. Clim. Environ. Res. 2018, 23, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Gu, L.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Z. Comparative Observational Study of the Surface Albedo between the Permafrost Region and the Seasonally Frozen Soil Region. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 2013, 71, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; He, T.; Liang, S.; Roujean, J.-L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X. Multi-Decadal Analysis of High-Resolution Albedo Changes Induced by Urbanization over Contrasted Chinese Cities Based on Landsat Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lei, C.; Chu, H.; Li, X.; Torn, M.; Wang, Y.-P.; Sciusco, P.; Robertson, G.P. Overlooked Cooling Effects of Albedo in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Qu, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, S.; Tang, H.; Liang, S. Preliminary Evaluation of the Long-Term GLASS Albedo Product. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2013, 6, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Qu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Guo, J.; et al. Review of Land Surface Albedo: Variance Characteristics, Climate Effect and Management Strategy. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, G.M.; Schwartz, S.E. The Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Program: Programmatic Background and Design of the Cloud and Radiation Test Bed. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1994, 75, 1201–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinty, B.; Lattanzio, A.; Martonchik, J.V.; Verstraete, M.M.; Gobron, N.; Taberner, M.; Widlowski, J.-L.; Dickinson, R.E.; Govaerts, Y. Coupling Diffuse Sky Radiation and Surface Albedo. J. Atmos. Sci. 2005, 62, 2580–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, H. A Rank-Invariant Method of Linear and Polynomial Regression Analysis. In Henri Theil’s Contributions to Economics and Econometrics; Raj, B., Koerts, J., Eds.; Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 23, pp. 345–381. ISBN 978-94-010-5124-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Chen, B.; Li, P.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Deng, J. Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Influencing Factors of Synergizing the Reduction of Pollution and Carbon Emissions—Utilizing Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data and GTWR Model. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 115775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ke, C.; Shao, Z. Winter Sea Ice Albedo Variations in the Bohai Sea of China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2017, 36, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Lin, X.; Luo, M.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, S.; et al. Vegetation Disturbance and Recovery Assessment through the Synergistic Effects of Albedo and Vegetation Index: Evidence from China’s Arid Regions. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.A.; Fabian, M.P.; Hutyra, L.R. Urban Green Space and Albedo Impacts on Surface Temperature across Seven United States Cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Barnes, M.; Yoder, L.; Williams, C.; Tank, J.; Royer, T.; Suttles, S.; Novick, K. The Potential for Albedo-Induced Climate Mitigation Using No-till Management in Midwestern U.S. Croplands. Commun. Earth Env. 2025, 6, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, D.; Tolba, O.; Kamel, T. The Impact of Increasing Urban Surface Albedo on Outdoor Air and Surface Temperatures during Summer in Newly Developed Areas. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, S.N.; Marshall, S.J.; Menounos, B. Temperature Mediated Albedo Decline Portends Acceleration of North American Glacier Mass Loss. Commun. Earth Env. 2025, 6, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Lai, H.-W. Spatiotemporal Variations of Land Surface Albedo and Associated Influencing Factors on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lin, X.; Bian, Z.; Lipson, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Liu, Q.; Grimmond, S.; Velasco, E.; Christen, A.; Masson, V.; et al. Satellite Observations Reveal a Decreasing Albedo Trend of Global Cities over the Past 35 Years. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 303, 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.K.; Yang, Z.; Erb, A.; Bright, R.M.; Domke, G.M.; Frescino, T.S.; Schaaf, C.B.; Healey, S.P. Integrating Albedo Offsets in Reforestation Decisions for Climate Change Mitigation Outcomes in 2050: A Case Study in the USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 587, 122699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Research on Land Desertification in Ejin Banner from 1991 to 2021 Based on Albedo-MSAVI Feature Space Model. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Bolch, T.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tan, S.; Afzal, M.M.; Tahir, A.A.; Shen, Y.; Wei, J.; et al. Seasonal and Interannual Variability of Karakoram Glacier Surface Albedo from AVHRR-MODIS Data, 1982–2020. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 253, 104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, W.; Wang, Z. Effect of Temperature and Water Content on Surface Albedo of Loess in Cold Regions and the Associated Mechanisms. J. Mt. Sci. 2025, 22, 1306–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Albedo-Driven Hydroclimatic Impacts of Large-Scale Vegetation Restoration Should Not Be Overlooked. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-T.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.-Q.; Du, Z.-C.; Ming, J. Global Glacier Albedo Trends over 2000–2022: Drivers and Implications. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2025, 16, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Yu, M.; Huo, P.; Lu, P.; Cheng, B.; Gao, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, L. Optimization of a Snow and Ice Surface Albedo Scheme for Lake Ulansu in the Central Asian Arid Climate Zone. Water 2025, 17, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Leng, G.; Yao, L.; Lu, C.; Han, S.; Fan, S. Disentangling the Contributions of Water Vapor, Albedo and Evapotranspiration Variations to the Temperature Effect of Vegetation Greening over the Arctic. J. Hydrol. 2025, 646, 132331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Qing, X.; Tan, S.; Gao, Y.; Qi, M.; Yi, Y.; Ye, H.; Afzal, M.M.; et al. Corrigendum to “Retrieval of High-Resolution Melting-Season Albedo and Its Implications for the Karakoram Anomaly” [Remote Sensing of Environment Volume 315 (2024) 114438]. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 315, 114474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, B.; Feng, Y.; Niu, J. Study on the Spatio-Temporal Change of Ecosystem Service Value in Henan Province. J. Xinyang Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2023, 36, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | 43.94% | 45.33% | 50.54% | 52.02% |

| Temperature | 27.48% | 28.07% | 27.54% | 26.81% |

| Precipitation | 28.57% | 26.61% | 21.91% | 21.17% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, J.; Wang, Z.; Lin, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Deng, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, T.; Zhu, J. Long-Term Trends and Seasonally Resolved Drivers of Surface Albedo Across China Using GTWR. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111287

Niu J, Wang Z, Lin H, Li H, Liu Z, Li M, Deng X, Wang B, Wu T, Zhu J. Long-Term Trends and Seasonally Resolved Drivers of Surface Albedo Across China Using GTWR. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(11):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111287

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Jiqiang, Ziming Wang, Hao Lin, Hongrui Li, Zijian Liu, Mengyang Li, Xiaodong Deng, Bohan Wang, Tong Wu, and Junkuan Zhu. 2025. "Long-Term Trends and Seasonally Resolved Drivers of Surface Albedo Across China Using GTWR" Atmosphere 16, no. 11: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111287

APA StyleNiu, J., Wang, Z., Lin, H., Li, H., Liu, Z., Li, M., Deng, X., Wang, B., Wu, T., & Zhu, J. (2025). Long-Term Trends and Seasonally Resolved Drivers of Surface Albedo Across China Using GTWR. Atmosphere, 16(11), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111287