1. Introduction

As industrialization and transport flows increase worldwide, atmospheric pollution is also increasing. Today, particulate matter air pollution is a global problem.

Particulate matter is a mixture of airborne particles and liquid droplets (aerosols) that may contain various components. The components can be very diverse, including acids, sulfates, nitrates, organic compounds, metals, soil particles, dust, and soot. Particulate matter also includes biological contaminants such as bacteria and fungi [

1]. Airborne particles vary in their physical and chemical composition, particle size, and emission sources.

During operation, diesel engines emit particles ranging in size from 50 nm to 1 µm. During cement production, many fine particles are released, half of which are smaller than 2.5 µm [

2,

3]. Scientists have conducted research in their work [

4] and confirm that industry and transport are the two largest sources of particulate matter (PM).

Of all the air pollutants, particulate matter is the most harmful to human health [

5]. Air pollution by particulate matter is a major problem in urban air quality [

6].

The most harmful effects are caused by particles, ranging in size from 10 to 2.5 μm. Particles of 2.5 μm in size enter the human body and cause serious health problems [

7,

8].

In order to minimize the entry of particles into the atmosphere, various new air purification methods and devices are being developed. Multi-stage air purification systems are used to clean the air from small particles, which use a lot of electricity. Such systems require large premises, as they are complex and expensive. For these reasons, scientists are constantly conducting experimental and numerical studies, the results of which would be used to create modern technologies for the effective deposition of small particles. One of such methods is particle agglomeration. Various factors can be applied to particle agglomeration, such as acoustics, chemistry, turbulence, etc. Indoor air quality has become a significant concern due to the negative impact of particles on health. Agglomeration is a promising way of particle bonding. Small particles combine with larger particles and, due to their increased mass, accumulate more effectively in filters. The results of experimental and numerical studies show [

9] that acoustic agglomeration significantly changes the size distribution of particles; when exposed to an acoustic field, the concentration of larger particles increases compared to small ones.

Experimental and numerical [

10,

11] studies show that acoustic agglomeration significantly changes the size distribution of particles, and the concentration of larger particles increases when exposed to an acoustic field compared to fine particles.

The efficiency of cyclonic cleaning for cleaning 1 µm particles reaches only 50% [

12].

Electrostatic filters can achieve particle removal efficiencies of 99.5% or more. However, PM2.5 removal efficiencies are only around 92–95%, and for particles between 0.1 and 1 μm, the efficiency is even lower [

13].

Air purification from particles smaller than 10 µm requires complex air purification systems; as small particles are dangerous, they can penetrate the lungs and other vital organs and absorb chemical pollutants [

14]. The respiratory tract can change the properties of PM2.5 entering the lungs. Using an in vitro model, researchers [

15] found that warm and humid conditions promote the desorption of nitrate (about 60%) and ammonium (about 31%) from PM2.5 during inhalation.

Particles agglomerate due to various mutual processes. When particles have a small diameter, they are affected by extremely strong van der Waals, electrostatic, and capillary forces. Together, these forces form an attractive force. Due to this force, the particles stick together and form larger compounds [

16].

In the work [

17], the agglomeration of monodisperse particles of different sizes (0.5 μm, 2 μm, and 4 μm) was researched under different parameters. The studies have shown that particles with a size of 4 μm agglomerated best in an acoustic field of 800–2400 Hz.

In article [

18], acoustic agglomeration of particles was modeled using the Direct Monte Carlo (DSMC) method, based on physical experiments. The results show that the method is effective, as the number of small particles has decreased, which means that they have agglomerated.

Experimental studies [

19] have been conducted to determine the influence of sound waves on cloud droplet agglomeration. Experiments were conducted at frequencies of 35–100 Hz and sound pressure levels of 112–122 dB. The conclusion of the studies is that the effect of cloud droplets on agglomeration is greater depending on sound pressure than sound frequency.

In order to improve the particle agglomeration effect by turbulent agglomeration, ref. [

20], a turbulent agglomerator was constructed in which whirls of different sizes are connected in the turbulent flow field. Experimental studies showed that combining whirls of different sizes in the turbulent flow field improves particle agglomeration. Sun et al. in work [

21] presented the three constructed types of turbulent agglomerators and the results of the conducted experiments. The results showed that the turbulent agglomerator with small whirls in the flow field had the greatest effect on agglomeration. Zhu and Tang [

22] researched the effects of sound pressure and sound frequencies on particle velocity and concentration distribution, as well as the sizes of bubbles and agglomerates.

In order to create an effective particle removal method, a new particle removal device was presented in the work [

23]. The operation of the particle removal device was evaluated experimentally. The effect of one external sound and two external sound fields was compared. It was found that the application of two external sound fields is more effective. The highest efficiency of 70% was obtained at a sound frequency of 1500 Hz, a sound pressure of 141 dB, and a cooling water flow of 560 l/h.

In article [

24], an ultrasonic study of 2.5 µm of particle removal was presented. A two-stage gas cleaning system consisting of an agglomerator and a cyclone was designed and manufactured. The studies showed that ultrasonic operation increases the cleaning efficiency of 2.5 µm particles from 46 to 85%. In [

25], an agglomerator with three agglomeration modes was proposed: turbulent agglomeration, atomized turbulent agglomeration, and charged turbulent agglomeration. The agglomeration results of 1 µm particles were distributed as follows: 21.8%, 53.2%, and 68.9%. When a filter was connected, the removal efficiency of 1 µm particles increased to 66.5%, 83.9%, 86.8%, and 89.7%.

The article [

26] describes studies conducted to determine the effect of ultrasound on the agglomeration of small particles. The results of the research showed that at a sound pressure of 160 dB, the agglomeration efficiency of 2.5 µm particles is 83%. Eddy currents increase the agglomeration efficiency by up to 13%.

In work [

27], the authors state that zeolites, especially alumina, can be very effective in removing PM. The removal of PM occurs due to electrostatic interactions, and alumina zeolites with charge-balancing cations can be effectively used to remove PM from the air. The method presented in work [

28], based on electro spraying, is used to assemble two-dimensional carbon nanostructured networks.

In work [

29], a combination of chemical and turbulent particle agglomeration was studied. It was found that chemical and turbulent agglomeration have different efficiencies, but both can be successfully applied to remove particles from industrial exhaust gases.

It is known that particles agglomerate when exposed to an acoustic field [

30,

31], but the principles of particle interaction are not yet fully understood. This hinders the development of new air pollution technologies. Therefore, it is necessary to continue to study the particle interaction factors that affect the efficiency of particle agglomeration.

Particle agglomeration depends on factors occurring only between particles and a gaseous medium (e.g., air). Technical solutions and methods are still being sought to increase the efficiency of agglomeration.

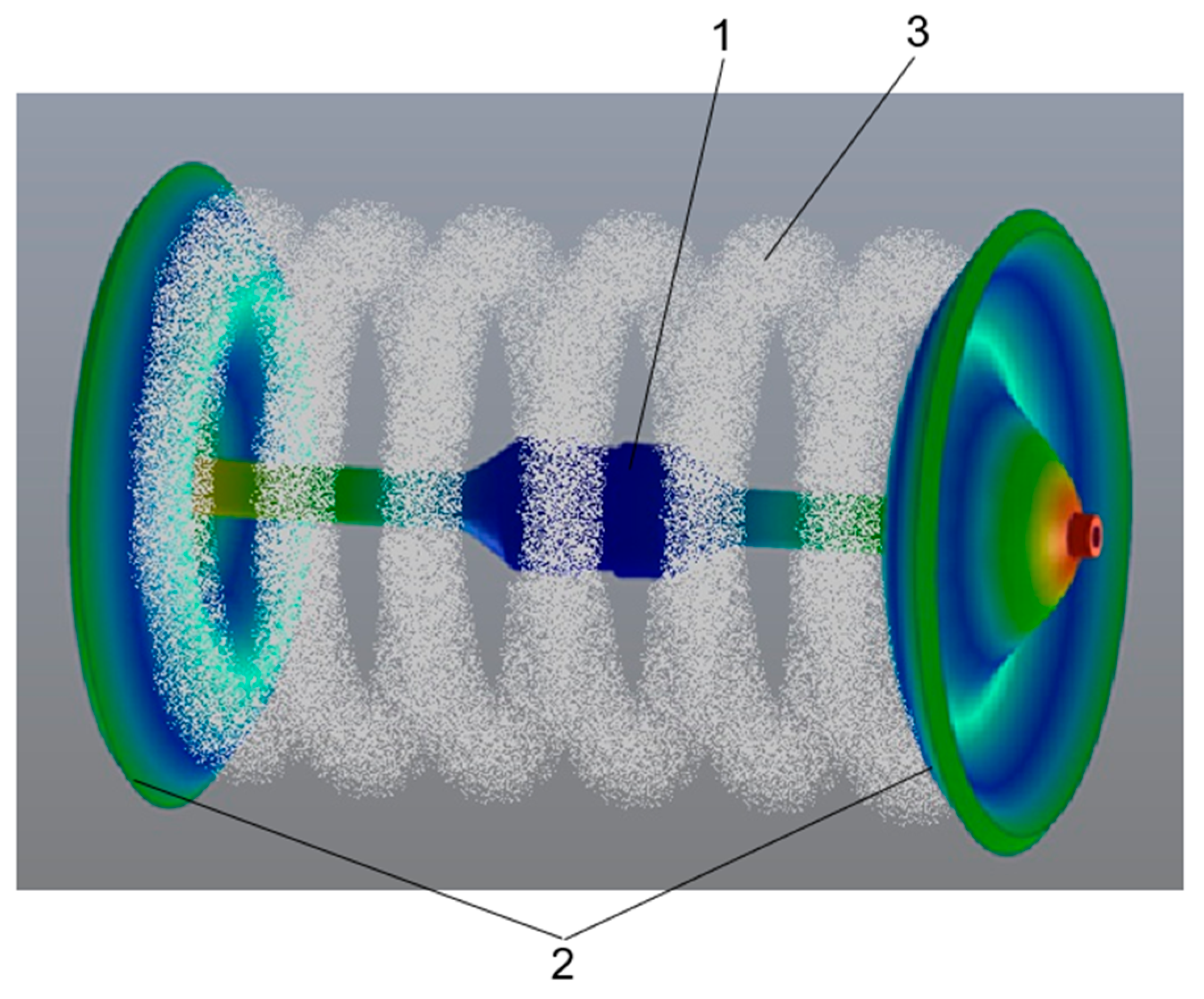

The novelty of the work is the validation and verification of a new design of a symmetrical piezoelectric ultrasonic vibration system (UVS). A UVS consists of a double bidirectional axial piezoelectric transducer with two disks arranged perpendicular to its axis of symmetry.

The aim of the research is to create a new design for the ultrasonic vibration system, with a double bidirectional axial piezoelectric transducer and two disks arranged perpendicular to its axis of symmetry, to prove that the UVS operates at a resonant frequency in the first mode with oscillation amplitudes that can be used to generate a strong acoustic field in air.

3. Physical Experimental Studies: Equipment and Methodology

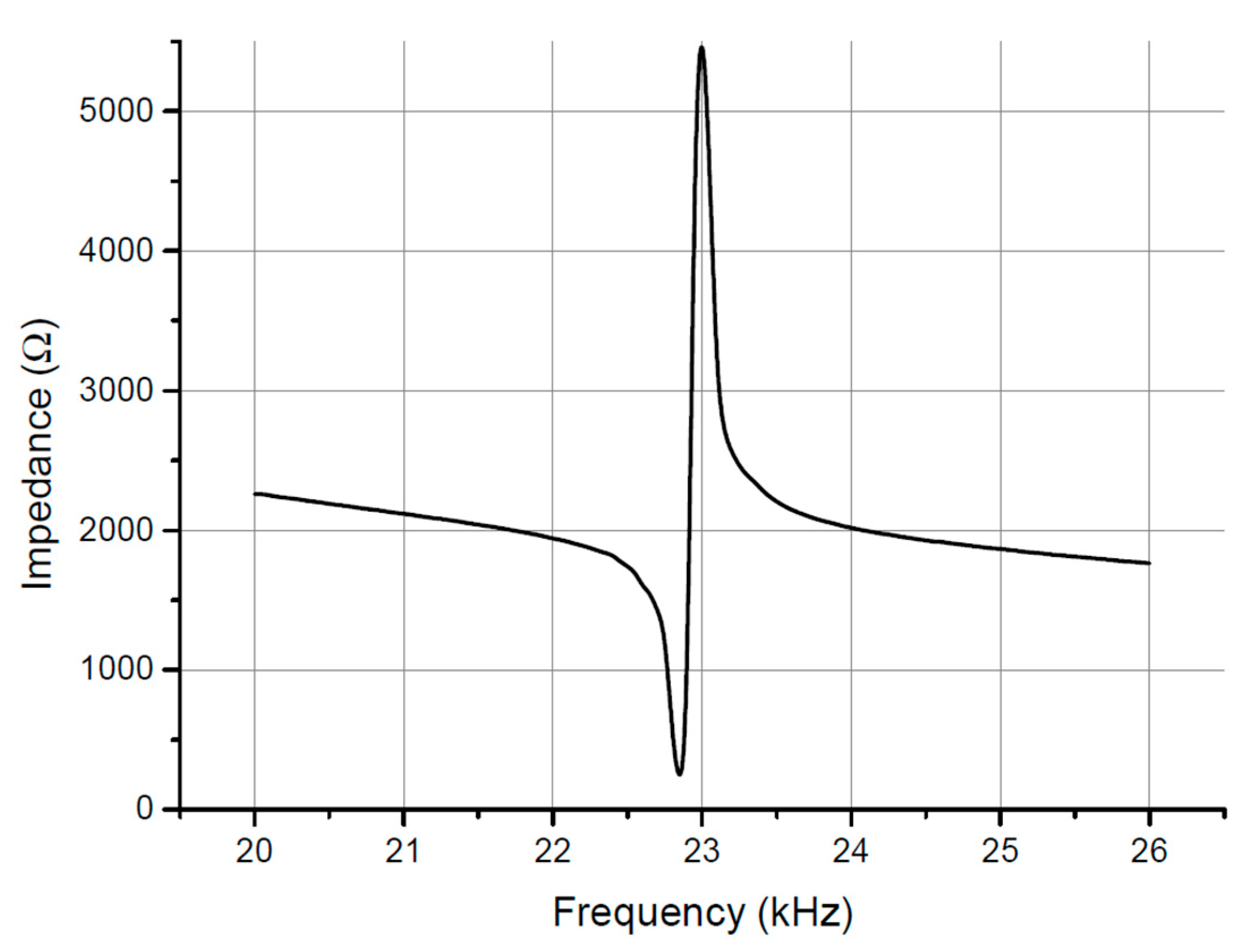

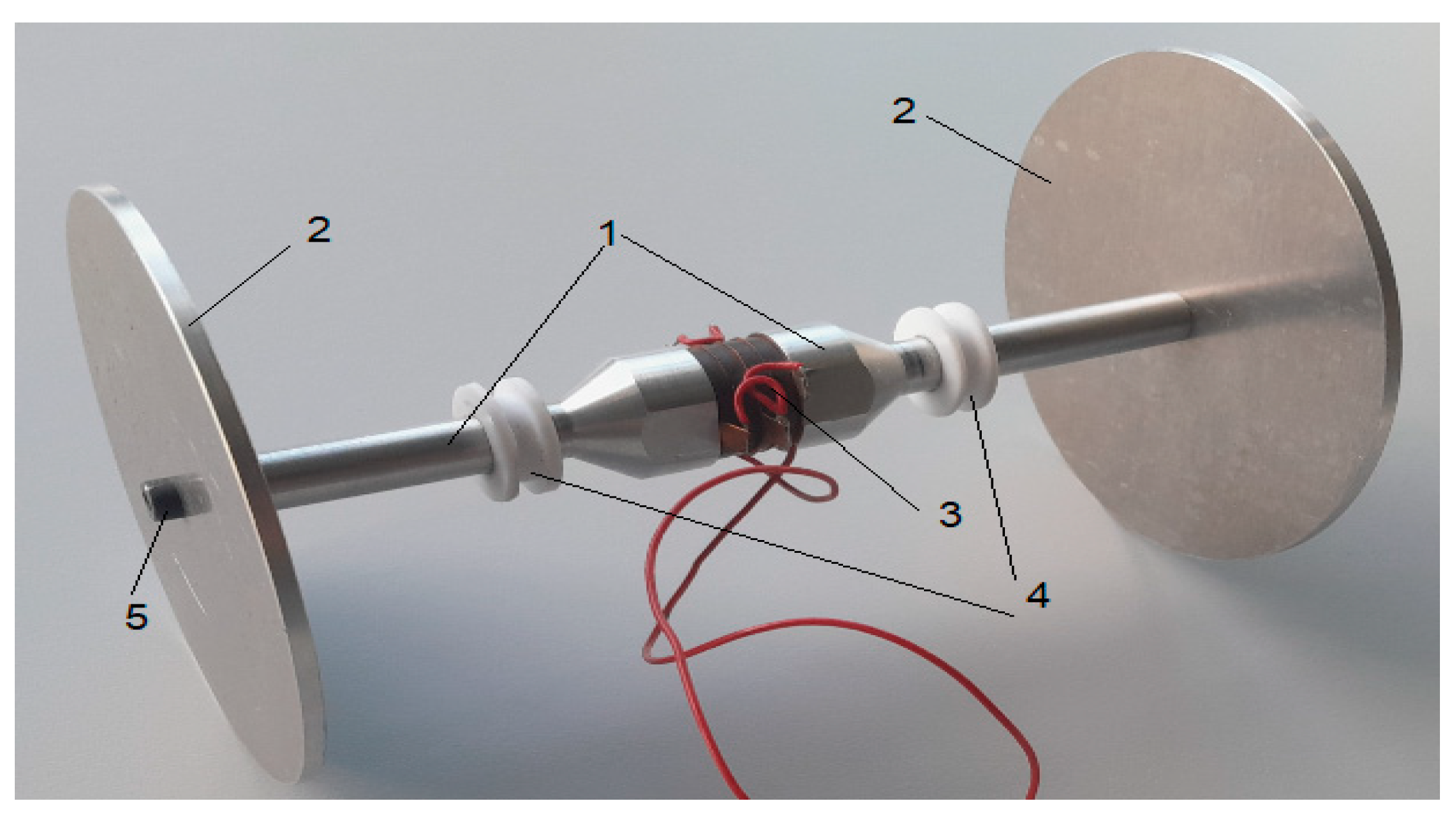

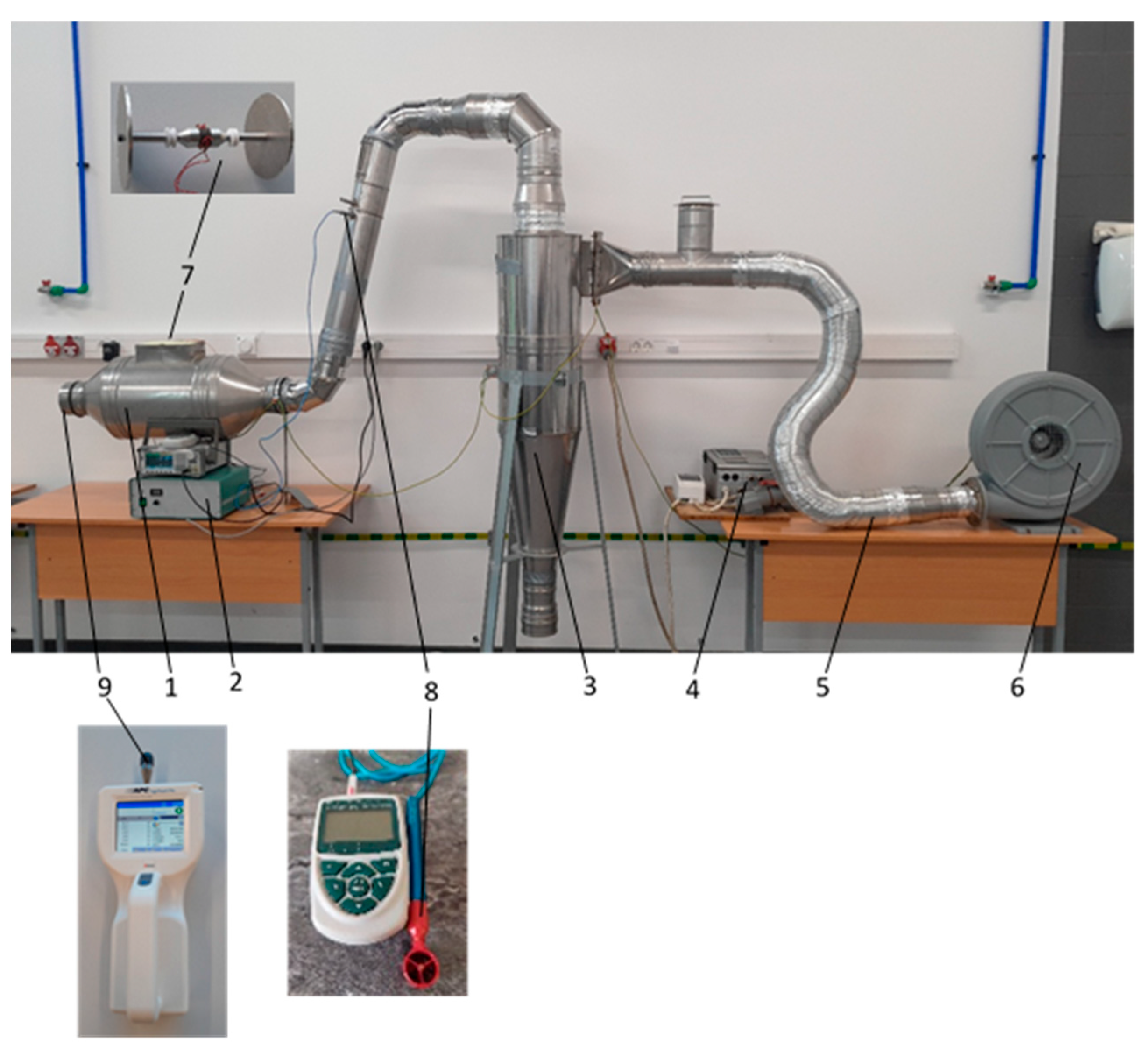

The UVS prototype (

Figure 3) was built to perform physical studies and validate the results of the numerical modeling. The prototype was built using the same materials and system dimensions as used in the numerical model.

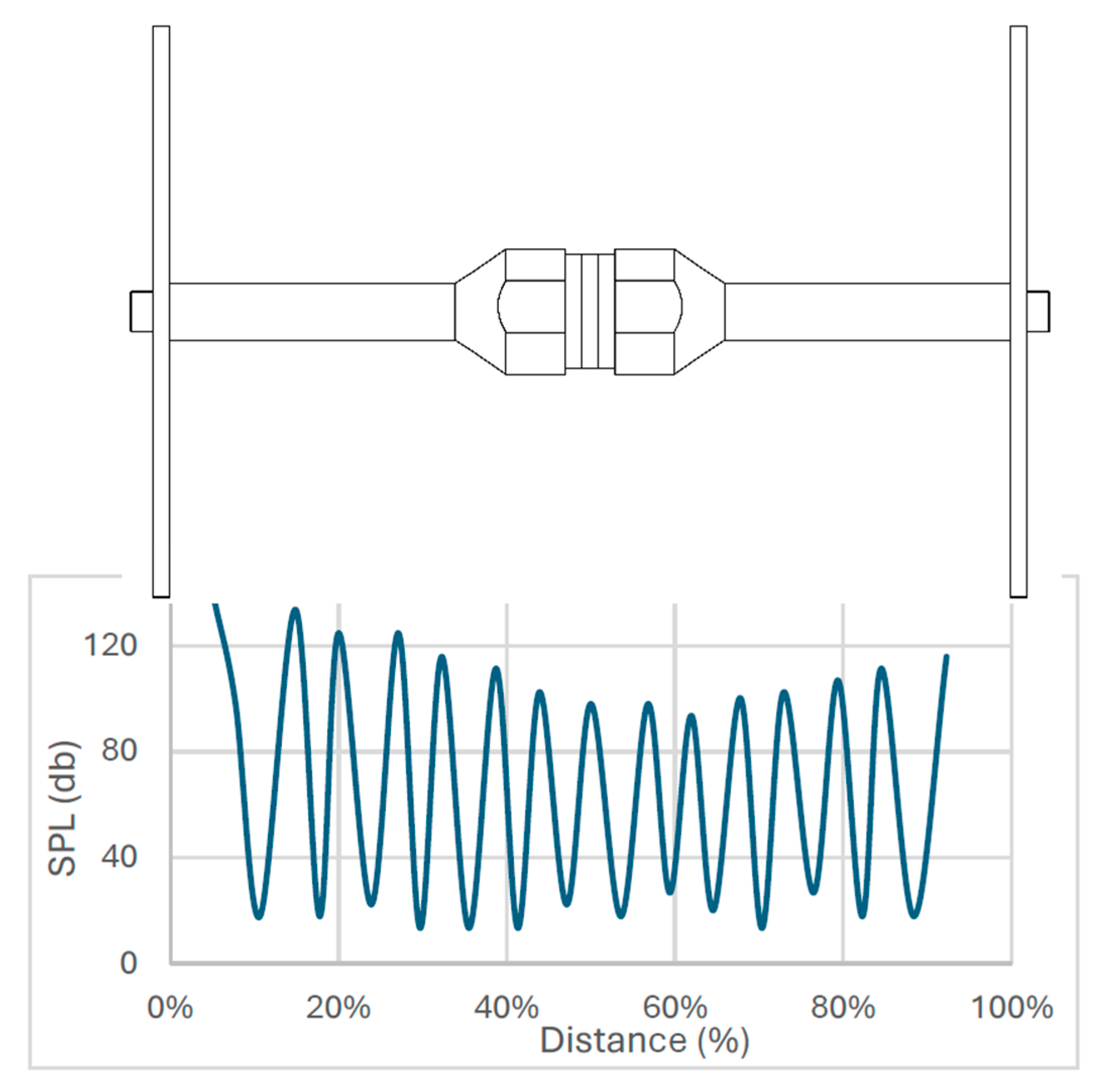

To determine the distribution of sound pressure in the air between the disks, sound pressure measurements were taken (

Figure 4). The microphone was moved cyclically from one UWS disk to the other, parallel to the system’s axis of symmetry. After determining the critical points (maximum or minimum pressure), the microphone was adjusted until the critical points of the curve were determined. The graph (

Figure 4) clearly shows the minimums and maximums; the graph is fairly symmetric. This shows that zones of high and low sound pressure form between the disks. The sound pressure level is shown by a curve in which the maximums and minimums are expressed in decibels. During the experiment, the UWS electrical power was 150 W. The maximum level of sound pressure was approximately 137 dB.

The operating principle of the experimental stand (

Figure 5) is as follows: a fan (6) supplies air flow from the environment to a cyclone (3), where particles larger than 10 µm in diameter are removed from the air flow. Furthermore, the fine particles move through the duct (5) to zone 1 where an ultrasonic two-disk piezoelectric transducer operates. In zone 7, the particle count was measured by a particle counter (9). Each measurement was repeated three times and the average of the results was calculated.

For this purpose, the UVS was installed in the air purification experimental device shown in

Figure 5.

The air flow velocity was measured using the ALMEMO 2590A measuring equipment (Ahl-born Mess- und Regelungstechnik GmbH, Holzkirchen, Germany); the measuring device consists of a counter and a speed sensor in (

Figure 4) position 8. An APC ErgoTouch Pro 2 particle counter was used to measure the amount of particles (

Figure 4) in position 9. This device allows real-time measurement of airborne particle concentrations and size distribution (factory calibration: 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 10.0 µm) in the range of 0.3–10 µm, ensuring high measurement accuracy with a measurement error of approximately ±5%.

During the physical experiment, the amount of solid particles in the environment and their size distribution from 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 µm were measured. The air flow velocity in the duct was maintained at 0.5 m/s and 1.3 m/s (which corresponds to a flow rate of 22.09 m3/h and 57.45 m3/h).

A methodology was developed for conducting physical research, according to which experimental tests were performed:

- -

The fan was turned on.

- -

Air flow velocity of 0.5 m/s or 1.3 m/s.

- -

Air flow was supplied from the environment (particle size: PM 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 10 μm).

- -

Large particles were deposited in the cyclone.

- -

The amount of particles was measured in the first measurement zone.

- -

The amount of particles was measured in the second measurement zone.

- -

The obtained measurement results from the particle counters were transferred to the computer.

- -

The analysis of the measurement results was performed.

Each measurement was repeated three times and the mathematical average was taken.

Before each new experiment, the device was checked for particulates by replacing the stainless steel isokinetic probe with a zero-count HEPA filter assembly and running the device in this mode for 10 min to remove any previously remaining particulates from the device.

4. Results and Discussion of Studies

This chapter presents results of a physical experiment and a numerical experiment on particle interactions.

Results of a Physical Experiment. In order to evaluate the efficiency of the system, measurements of particle concentrations and particle size distribution before and after acoustic exposure were performed using a symmetric piezoelectric UVS. Experimental measurements were performed according to the presented research methodology.

Experimental studies were carried out with particles up to 10 μm in size. Larger particles in the air stream were separated and deposited in a cyclone. After the cyclone, up to 0.1% of particles were recorded in the air stream and 10 μm in size, and 99.9% of particles were smaller than 10 μm. The majority were particles of 0.3 μm in size. These particles are the most harmful to human health. Smaller particles spread more easily in the environment and enter the human body more easily. The measurements showed that in the acoustic field, as the air stream moved, agglomeration of particles occurred.

The results of the research are presented in

Table 1. It can be seen that the application of ultrasound has an effect, because the number of fine particles decreased after the effect of ultrasound, and the number of larger particles increased. This means that the fine particles agglomerated into larger ones.

Although the effect is relatively small, it is clear that the proposed UVS has the potential for particle agglomeration. Therefore, more detailed study and optimization of process parameter dependencies are required.

Results of a Numerical Experiment on Particle Interactions. Simulation addresses the normal impact of two smooth spherical silica particles of radius R

1 = 0.15 μm and R

2 = 0.25 μm, respectively. Density ρ of the particles is approximately ρ

1,2 = 2000 kg/m

3 or 2 g/cm

3. The mass of the silica particle can be calculated as follows:

The particles are assumed to be relatively smooth on a subnanometer scale. Mass (m) of silica spheres was m

1 = 0.449 × 10

−16 kg and m

2 = 1.309 × 10

−16 kg, respectively. Other values of the property parameters are selected from sources [

32] and experimental results performed with AFM (Tykhoniuk et al. [

33]). Elastic constants of the modulus is given as E

1,2 = 75 GPa; Poisson’s ratio is ν

1,2 = 0.17. Elasticity parameters of the substrate are identical to those of the particle. Adhesion parameters are Hamaker constant C

H ≈ 3.216 ×·10

−20 J; separation distance at zero load is a

F=0 = 0.336 nm; adhesion force F

h=0 = 5.0 nN is back-calculated from shear experimental test results of industrial silica powder for particles (Jasevičius et al. [

34]).

Assumptions. In the device, the particles move with the air flow and therefore have the similar/same velocity. It is assumed that under these conditions, when the moving particles are very close to each other (less than half a nanometer), the effect of air resistance (the difference in the velocity of particles moving in the flow due to the effect of the air flow) is negligible. Under these conditions, it is assumed that the difference in particle velocities arises from the effect of the acoustic field and the force of adhesion. Adhesion is understood as the interaction of identical/similar (same material) particles.

The smallest particles were selected, with sizes of 0.3 µm and 0.5 µm. They are the most difficult to extract, but they easily penetrate the lungs and are considered the most dangerous. It was important to determine whether acoustics could extract the smallest particles by agglomeration. The effects of fine particles are discussed in this publication [

35]. Here, particles that are 100 nm and 300 nm in size have already been studied.

The interparticle distance is assumed to be about 0.336 nm, at which the effect of adhesion is significant. This study examines the interaction of particles separated by a small distance of less than a nanometer. This distance is sufficient for adhesion to be significant. This is important, as adhesion determines particle adhesion. Given the vanishingly small distance and nanosecond time, it is assumed that turbulence will not distort the particle trajectory for interactions lasting several nanoseconds.

The study of Brownian motion is an application of the stochastic method, which is more suitable for describing the random motion of molecules. This paper numerically analyzes the dynamics of particle interactions of the appropriate size. When the interaction/motion is determined by forces characteristic of the interaction, the motion is not stochastic and random. The influence of the Brownian force itself is negligible and has no effect on motion, since the paper evaluates particle dynamics, their mass, and contact deformation. The following article analyzed the Brownian force, which has no significant effect on particle dynamics [

36].

The motion of ultrafine particles moving close to each other is assumed to be determined by the air flow of the air purifier. During the corresponding vanishingly small time interval, when the particles move at the same speed, the relative velocity is assumed to be zero. The relative velocity of interaction arises due to the acoustic effect. In this case, interaction is possible when a relative velocity arises that creates the initial conditions for particle aggregation.

Based on the Dianov diagram, an appropriate initial interaction velocity of 0.35 m/s was chosen for the smallest particles due to the acoustic effect. Dianov’s research is presented in the following publications [

11,

37].

Unfortunately, it is physically impossible to observe such processes with a high-speed camera. Therefore, a numerical experiment is important because it complements the physical experiment, allowing predictions of particle behavior that are impossible to observe with modern equipment. It is important to note the nuances of the interaction, specifically, during the interaction, as particles are deformed only in the contact zone (nanometers) and the interaction itself lasts for nanoseconds. The initial data on the particles is taken from known physical experiments.

It can also be noted that in this work, the frequency of acoustic oscillations is about 22 kHz, and one oscillation lasts about 45 μs. The duration of particle interaction is 6 ns, which is approximately 7500 times shorter than the time required for a single oscillation due to the acoustic effect. Consequently, the acoustic force itself is irrelevant over a vanishingly small-time interval. The effect/influence of the acoustic force is considered as a history, that is, as the difference in velocities caused by the influence of acoustics. The adhesion force, however, is important for agglomeration/sticking itself, which plays a decisive role.

The Need For a Numerical Experiment. Although a physical experiment observes particle agglomeration, it is still difficult to answer whether particles can stick together under the influence of an acoustic field. That is, it is physically difficult to observe the agglomeration of particles as they move in an air flow. Therefore, the results of a physical experiment are often limited to analyzing the filtered air, without delving into the process of particle agglomeration as they move in a flow. A numerical experiment allows us to analyze the interaction of particles at each time step, which allows us to predict the behavior of ultrafine particles and predict the air purification process. The numerical experiment was carried out taking into account the initial data given in

Table 2.

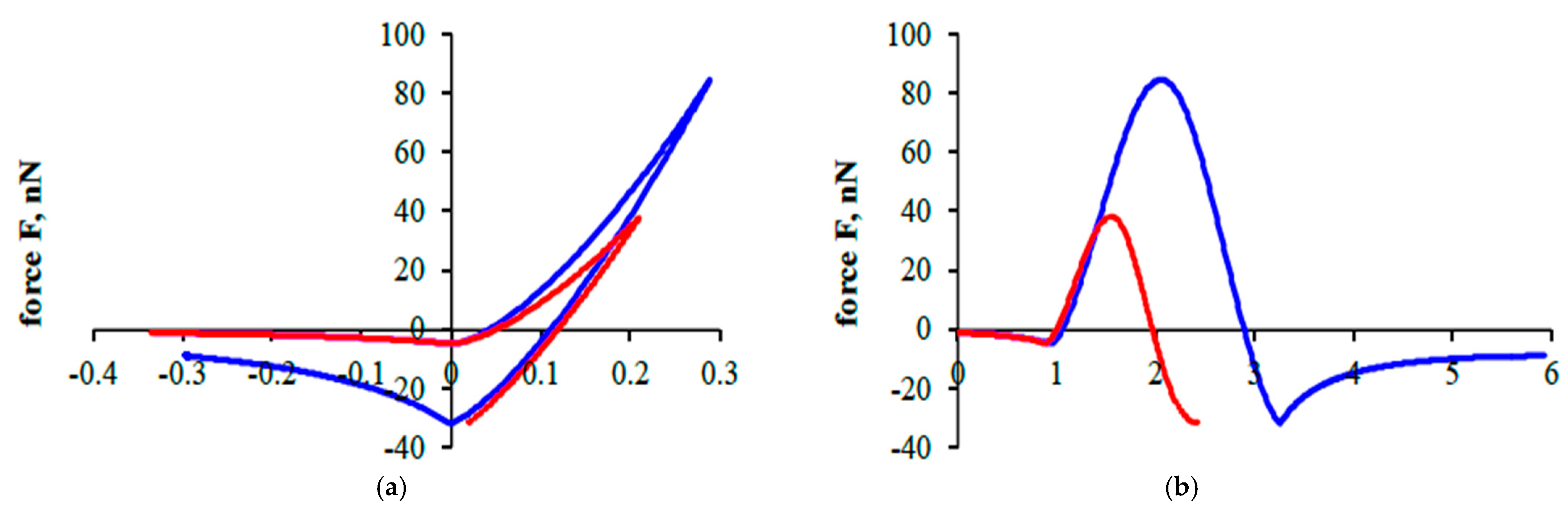

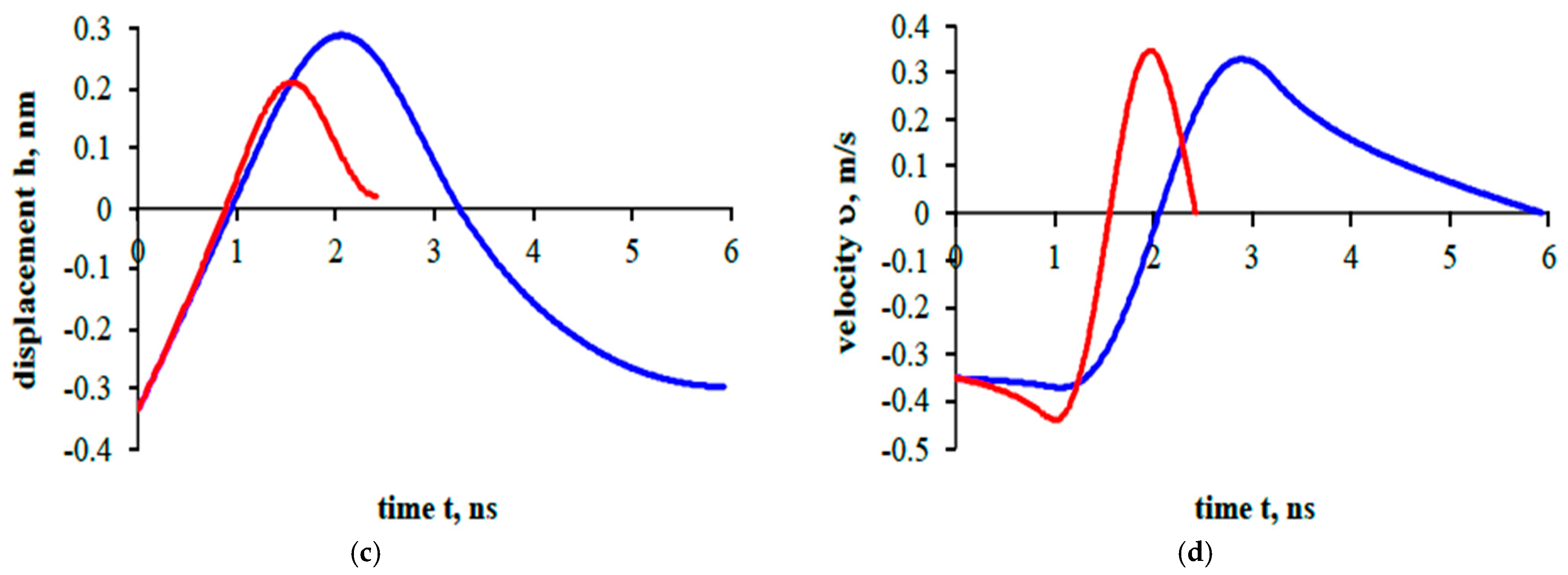

Figure 6 shows the interaction of two particles of the same diameter.

The interaction of particles with a diameter of

m is shown in red. The case of interaction of particles with a diameter of

m is shown in blue. The velocity of particle interaction (the difference in particle velocities) is chosen taking into account the influence of the acoustic field based on Dianov’s solution [

38]. The initial velocity (under the influence of the acoustic field) of the particles is 0.35 m/s.

In the graphs showing the results of particle interactions, a negative displacement corresponds to the interaction of particles that are at a certain distance from each other, and a positive displacement corresponds to the interaction of particles that are in contact. A positive resultant force corresponds to repulsion, and a negative resultant force corresponds to attraction.

The motion of particles is described using Newton’s second by Jasevičius et al. [

34], Jasevičius [

38]:

where

and vector

xi are the mass and position of the

i-th particle, and vector

corresponds to the resultants of forces added up and acting on the center of particle

i during a possible interaction. The integration of Equation (1) for a particle at time

(where

is the time step) is performed numerically by applying a fifth order Gear’s predictor–corrector scheme, as stated by Jasevičius et al. [

34], Jasevičius [

38].

The forces (resultant force) acting on a particle can be described by the following general expression:

where

is adhesion force;

is drag force;

is elastic force;

is energy dissipation force. Considering the aforementioned information, for particle interaction in the air flow (both particles has similar velocity) at extremally small distance (half nanometer or less) during the interaction, the acting forces are as follows:

In

Figure 6, the interaction is divided into various interaction action parts (approach, loading, unloading, and detachment), as described by Jasevičius et al. [

34], Jasevičius [

38]. First interaction at a distance (negative displacement) is called approach; this is followed by contact with loading and unloading, and finally detachment when interaction is at a distance. It is important to mention that if particles do not have enough initial kinetic energy to rebound, they will stick together.

In

Figure 6, particles with radius R

1 = 0.15 μm and R

2 = 0.25 μm sticked together. In both cases (red, blue line), there was not enough kinetic energy to reach its initial interaction position. The following sticking processes are not analyzed here, as it needs more research. In this work, research is needed to analyze how particles of different sizes behave. In order to achieve that, there is a need to consider the particles in different scenarios. Smaller particles during interaction (

Figure 6a,b) reach smaller repulsion forces (smaller particles are considered to be about ≈38 nN, a nanonewton scale) in comparison with bigger ones (larger particles are considered to be about ≈84 nN). The interaction duration (

Figure 6b–d) was twice larger for interactions between particles that are considered to be bigger. Also, in

Figure 6a,c, particles considered to be larger have larger displacement (≈0.29 nm, nanometers scale) in comparison with particles considered to be smaller (≈0.21 nm). Larger velocity values are achieved (

Figure 6d) for particles that are considered to be smaller, while at the same time, interaction duration, as mentioned, is twice smaller.

For the results of this study, it is important to mention that ultrafine particles tend to stick together (in both cases, particles of different diameters stuck together), while it could be challenging to stick them together in air flow. This is because they both have similar velocity and are extremely small in size. Due to this, acoustic field could play a key role if small pollution particle agglomeration is needed for better filtering efficiency.