Runoff and Sediment Response to Rainfall Events in China’s North-South Transitional Zone: Insights from Runoff Plot Observations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. K-Means Clustering of Rainfall

2.3.2. Effects of Individual Rainfall Events on Runoff and Sediment Yield

3. Results

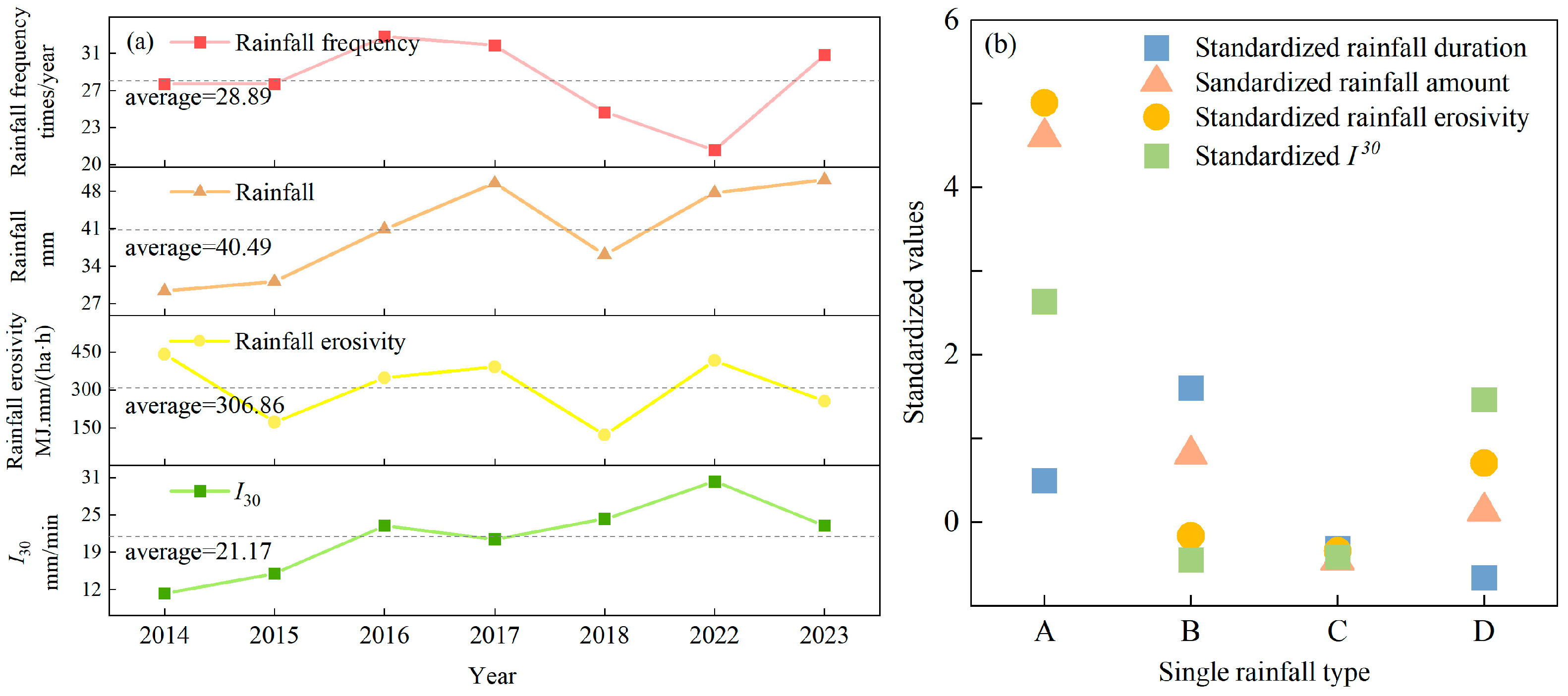

3.1. Rainfall Event Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics of Runoff and Sediment Yield Under Different Slope Gradients

3.3. Effects of Rainfall on Runoff and Sediment Yield

3.3.1. Effects of Rainfall Characteristics on Runoff and Sediment Yield

3.3.2. Effects of Rainfall Types on Runoff and Sediment Yield

3.4. Comparison of Soil and Water Conservation Benefits

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Slope Gradient on Runoff and Sediment Yield

4.2. Effects of Different Land Use Types on Runoff and Sediment Yield

4.3. Runoff and Sediment Generation Responses to Single Rainfall Events

5. Conclusions

- From 2014 to 2023, Type C rainfall was the dominant type in China’s North-South Transition Zone, marked by low precipitation, intensity, erosivity, and short duration. These events occurred mainly between April and October, with an annual frequency of approximately 29.

- Runoff and sediment yield varied significantly across slopes and land use types in the study area. Bare land exhibited the highest values, especially at 15° slope, while grassland showed the lowest.

- Rainfall amount demonstrated a positive correlation with runoff and sediment yield. Soil loss rates (runoff depth) across all slopes showed significant correlations with rainfall indices, with rainfall intensity being the dominant factor. Among rainfall types, Type D generated the highest sediment yield, while Type A produced the greatest runoff volume, followed by Type B and Type C.

- All land types showed greater sediment reduction than runoff reduction. On 15° slopes, grassland remained most effective, followed by forest. On 25° slopes, forest and grassland maximized runoff reduction. Grass-planting was the most effective measure on 10° and 15° slopes, whereas both afforestation and grass-planting were optimal on the 25° slopes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Ma, B.B.; Lu, C.X.; Yang, H.; Sun, M.Y. Spatial pattern and development of protected areas in the North-South Transitional Zone of China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Zhu, L.Q.; Li, G.L.; Zhao, F.; Qin, L.T. Distribution patterns of SOC/TN content and their relationship with topography, vegetation and climatic factors in China’s North-South Transitional Zone. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.J.; Weng, X.R.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Xu, T.B.; Ye, Y. Characteristics of erosive rainfalls in Chongqing City based on cluster analysis. J. Water Res. Water Eng. 2021, 32, 19–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Niu, J.Z. Analysis of properties and problem about artificial rainfall simulation tests. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2012, 19, 278–283. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Baver, L.D. Ewald Wollny: A pioneer in soil and water conservation research. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1939, 3, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.F. Waste through soil erosion. Agron. J. 1926, 18, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Prosser, I.P.; Moran, C.J.; Gallant, J.C.; Priestley, G.; Stevenson, J.G. Predicting sheet wash and rill erosion over the Australian continent. Soil Res. 2003, 41, 1037–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, O.; Govers, G.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Van Oost, K.; Poesen, J.; Saby, N.; Gobin, A.; Vacca, A.; Quinton, J.; Auerswald, K.; et al. Rates and spatial variations of soil erosion in Europe: A study based on erosion plot data. Geomorphology 2010, 122, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.D. Evolution of the universal soil loss equation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1984, 39, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Y.; Zhang, K.L.; Xie, Y. An Empirical Soil Loss Equation. In Proceedings of the 12th International Soil Conservation Organization Conference, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 26–31 May 2002; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall-Erosion Losses from Cropland East of the Rocky Mountains; Agricultural Handbook No. 282; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1965.

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall Erosion Losses: A Guide to Conservation Planning; Agriculture Handbook; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; p. 537.

- Xiong, M.Q.; Sun, R.H.; Chen, L.D. Global analysis of support practices in USLE-based soil erosion modeling. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2019, 43, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Jiao, J.Y.; Rayburg, S.; Wang, Q.L.; Su, Y. Soil erosion resistance of “Grain for Green” vegetation types under extreme rainfall conditions on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2016, 141, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Borja, M.E.; Úbeda, X.; Martínez-Murillo, J.F.; Keesstra, S. Pinus halepensis M. versus Quercus ilex subsp. Rotundifolia L. runoff and soil erosion at pedon scale under natural rainfall in Eastern Spain three decades after a forest fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 400, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.P.; Abla, M.; Lü, D.; Yan, R.; Ren, Q.F.; Ren, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhao, W.H.; Lin, P.F.; et al. Effects of vegetation and rainfall types on surface runoff and soil erosion on steep slopes on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2018, 170, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Li, B.B.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, G.B. Effects of Bothriochloa ischaemum characteristics induced by nitrogen addition on the process of slope runoff and sediment. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Li, Y.M.; Yan, J.F.; Gu, Z.J.; Zhang, H.F.; Li, P.Y.; Huang, S.P. Effects of different land uses on runoff and sediment on sloping land in Loess Hilly Area of Westen Henan. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 31, 67–74, 85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Wang, S.J. Effects of land use, land cover and rainfall regimes on the surface runoff and soil loss on karst slopes in southwest China. Catena 2012, 90, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, P.L.; Deng, R.F.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.F. Erosion characteristics of plots with various underlying surfaces in single rainfall. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2011, 31, 99–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.F.; Chen, L.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, D.T. Effect of land use pattern on runoff and sediment yield on slope lands in Loess Hilly Region. J. Ecol. Rual Environ. 2010, 26, 199–204. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Ma, L.N.; Wang, Q.R. Characteristics of runoff and sediment on slope land with different land use in karst trough valley area. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 41, 49–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.W.; Deng, H.; Li, R.S.; Li, Y.Q.; Yang, G.B.; Deng, O. Plot-Scale Runoff Generation and Sediment Loss on Different Forest and Other Land Floors at a Karst Yellow Soil Region in Southwest China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Qin, W.; Ding, L.; Ma, T.; Xin, Z.B.; Liu, Q. Exploring the impact of rainfall spatial differentiation on sediment yield of a typical watershed in the Loess Plateau of China. Catena 2025, 258, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Wang, M.S.; Zheng, W.; Song, Y.Y.; Huang, X.J. A multi-level spatial assessment framework for identifying land use conflict zones. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Nicolau, M.; Merino, L.; Merino, L.; Wilcox, B.P. Plot scale effects on runoff and erosion along a slope degradation gradient. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W04503. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, B.; Tang, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, X. Hydrological processes and sediment yields from hillslope croplands of regosol under different Slope Gradients. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhao, Q.H.; Cao, Z.H.; Ding, S.Y. Inhibiting effects of vegetation on the characteristics of runoff and sediment yield on riparian slope along the lower Yellow River. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Chen, L.D.; Zhang, H.D.; Chen, J. Effect of rainfall variation and landscape change on runoff and sediment yield from a loess hilly catchment in China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Fang, N.F.; Zhang, P.C.; Shi, Z.H. Impacts of land use change on watershed stream flow and sediment yield: An assessment using hydrologic modeling and partial least squares regression. J. Hydrol. 2013, 484, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeau, J.L.; Bricquet, J.P.; Planchon, O.; Valentin, C. Soil crusting and in filtration on steep slopes in northern Thailand. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2003, 54, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, T.W.; Cai, C.F.; Li, Z.X.; Cheng, D.B. Effects of vegetation on runoff generation, sediment yield and soil shear strength on road-side slopes under a simulation rainfall test in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 485, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnell, P.I.A. Raindrop-impact-induced erosion processes and prediction: A review. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 2815–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, L.J.; Dakessian, S. Soil reinforcement by roots: Calculation of increased soil shears resistance from root properties. Soil Sci. 1981, 132, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Yang, J.; Hu, J.M.; Tang, C.J.; Zheng, H.J. Characteristics of the surface-subsurface flow generation and sediment yield to the rainfall regime and land-cover by long-term in-situ observation in the red soil region, Southern China. J. Hydrol. 2016, 539, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.N.; Almeida, A.C.; Coelho, C.O.A. Impacts of land use and cover type on runoff and soil erosion in a marginal area of Portugal. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearing, M.A.; Jetten, V.; Baffaut, C. Modeling response of soil erosion and runoff to changes in precipitation and cover. Catena 2005, 61, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, G.Q.; Huang, G.H. Modeling of state of vegetation and soil erosion over large areas. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2008, 23, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiry, M.K.; Said, S.; Ansari, S.A. Analysis of surface runoff and sediment yield under simulated rainfall. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023, 9, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.Y.; Liu, J.G.; Ma, J.G.; Li, H.; Ma, B.J.; Li, J.M.; Li, C.H.; Li, B.X.; Liu, Y. Research of Runoff and Sediment Yields on Different Slopes of Lancang River Arid Valley Under Natural Rainfall Conditions. Water 2025, 17, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.X.; Tian, P.; Mu, X.M.; Zhao, G.J.; Zhang, Y.T. Sediment load variations and the driving forces in the typical drainage basins of the north-south transitional zone of China. Mt. Res. 2023, 41, 169–179. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Rainfall Types | Frequency | Rainfall Characteristic Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation | Mean | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4 | T/min | 870.00 | 2030.00 | 645.97 | 1477.50 | 0.44 |

| P/mm | 170.00 | 233.00 | 17.77 | 206.13 | 0.09 | ||

| Rc/MJ·mm·ha−1·h−1 | 2143.23 | 4353.81 | 72.92 | 3694.99 | 0.02 | ||

| I30/mm·h−1 | 43.30 | 98.69 | 7.16 | 72.12 | 0.10 | ||

| B | 38 | T/min | 1250.00 | 5090.00 | 937.97 | 2472.87 | 0.38 |

| P/mm | 22.50 | 156.00 | 25.34 | 69.60 | 0.36 | ||

| Rc/MJ·mm·ha−1·h−1 | 0.00 | 975.00 | 777.37 | 196.51 | 3.96 | ||

| I30/mm·h−1 | 0.00 | 35.30 | 9.59 | 12.01 | 0.80 | ||

| C | 118 | T/min | 15.00 | 1970.00 | 836.86 | 736.56 | 1.14 |

| P/mm | 5.90 | 79.50 | 41.30 | 24.19 | 1.71 | ||

| Rc/MJ·mm·ha−1·h−1 | 0.00 | 340.80 | 731.52 | 75.11 | 9.74 | ||

| I30/mm·h−1 | 0.00 | 39.30 | 21.13 | 12.72 | 1.66 | ||

| D | 38 | T/min | 25.00 | 2110.00 | 1042.08 | 422.97 | 2.46 |

| P/mm | 6.90 | 106.00 | 26.77 | 45.30 | 0.59 | ||

| Rc/MJ·mm·ha−1·h−1 | 9.57 | 3587.00 | 340.09 | 784.97 | 0.43 | ||

| I30/mm·h−1 | 26.80 | 82.57 | 19.88 | 49.30 | 0.40 |

| Land Use Type | Runoff Depth (mm) | Runoff Coefficient | Sediment Concentration (g·L−1) | Soil Loss Rates (t·ha−1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | |

| Grassland | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Dry land | 3.49 | 4.22 | 2.32 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 20.67 | 29.21 | 6.02 | 2.18 | 3.22 | 0.87 |

| Forest land | 1.54 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| Bare land | 6.45 | 7.48 | 7.43 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 102.12 | 135.97 | 183.78 | 11.12 | 14.94 | 22.42 |

| Natural vegetation | 4.89 | 5.35 | 2.18 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 7.09 | 7.52 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.03 |

| Variables | 10° | 15° | 25° | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Loss Rates (t·ha−1) | Runoff Depth (mm) | Soil Loss Rates (t·ha−1) | Runoff Depth (mm) | Soil Loss Rates (t·ha−1) | Runoff Depth (mm) | |

| I30 | 0.124 ** | 0.393 ** | 0.195 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.214 ** | 0.333 ** |

| Vc | −0.234 ** | −0.187 ** | −0.213 ** | −0.130 ** | −0.273 ** | −0.174 ** |

| P | 0.108 * | 0.499 ** | 0.137 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.108 ** | 0.459 ** |

| Rc | 0.053 | 0.409 ** | 0.118 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.498 ** |

| L | −0.029 | 0.143 ** | −0.038 | 0.080 * | 0.033 | 0.094 * |

| T | −0.055 | 0.017 | −0.091 * | 0.002 | −0.099* | 0.014 |

| Rainfall Types | Runoff Characteristic Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Runoff Depth/mm | 11.13 | 64.39 | 25.91 |

| Runoff Coefficient | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.12 | |

| Sediment Concentration/g·L−1 | 2.9 | 32.13 | 17.13 | |

| Soil Loss Rates/t·ha−1 | 1.11 | 8.36 | 4.31 | |

| B | Runoff Depth/mm | 0 | 21.00 | 2.94 |

| Runoff Coefficient | 0 | 0.14 | 0.02 | |

| Sediment Concentration/g·L−1 | 0 | 174.78 | 10.13 | |

| Soil Loss Rates/t·ha−1 | 0 | 31.81 | 1.33 | |

| C | Runoff Depth/mm | 0 | 15.48 | 1.21 |

| Runoff Coefficient | 0 | 2.01 | 0.04 | |

| Sediment Concentration/g·L−1 | 0 | 204.94 | 6.73 | |

| Soil Loss Rates/t·ha−1 | 0 | 8.74 | 0.30 | |

| D | Runoff Depth/mm | 0.42 | 61.00 | 6.87 |

| Runoff Coefficient | 0 | 0.40 | 0.10 | |

| Sediment Concentration/g·L−1 | 0 | 312.69 | 34.67 | |

| Soil Loss Rates/t·ha−1 | 0 | 34.91 | 4.18 |

| Land Use Types | Runoff Reduction/mm | Sediment Reduction/t·ha−1 | Runoff Reduction Efficiency/% | Sediment Reduction Efficiency/% | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | 10° | 15° | 25° | |

| Grassland | 6.45 | 7.45 | 7.39 | 11.12 | 14.94 | 22.42 | 100 | 99.58 | 99.51 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dry land | 2.97 | 3.26 | 5.11 | 8.94 | 11.73 | 21.55 | 45.99 | 43.55 | 68.76 | 80.40 | 78.48 | 96.14 |

| Forest land | 4.91 | 5.04 | 7.43 | 11.03 | 14.46 | 22.42 | 76.14 | 67.35 | 100 | 99.21 | 96.79 | 100 |

| Natural vegetation | 1.56 | 2.13 | 5.25 | 10.58 | 14.26 | 22.39 | 24.24 | 28.50 | 70.66 | 95.11 | 95.46 | 99.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, Z.; Ji, K.; Xu, G.; Reheman, M.; Feng, D.; Shen, Y.; Yi, Q.; Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Pan, S. Runoff and Sediment Response to Rainfall Events in China’s North-South Transitional Zone: Insights from Runoff Plot Observations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101207

Gu Z, Ji K, Xu G, Reheman M, Feng D, Shen Y, Yi Q, Kang J, Zhang X, Pan S. Runoff and Sediment Response to Rainfall Events in China’s North-South Transitional Zone: Insights from Runoff Plot Observations. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(10):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101207

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Zhijia, Keke Ji, Gaohan Xu, Maidinamu Reheman, Detai Feng, Yi Shen, Qiang Yi, Jiayi Kang, Xinmiao Zhang, and Sitong Pan. 2025. "Runoff and Sediment Response to Rainfall Events in China’s North-South Transitional Zone: Insights from Runoff Plot Observations" Atmosphere 16, no. 10: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101207

APA StyleGu, Z., Ji, K., Xu, G., Reheman, M., Feng, D., Shen, Y., Yi, Q., Kang, J., Zhang, X., & Pan, S. (2025). Runoff and Sediment Response to Rainfall Events in China’s North-South Transitional Zone: Insights from Runoff Plot Observations. Atmosphere, 16(10), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101207