Effects of Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Boundary Conditions for Uneven Terrain on Pollutant Dispersion from Nuclear Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Atmospheric Dispersion Tracer Experiments

2.1. SF6 Leakage Experiment Environment

2.2. Experiment Preparation

2.3. Experiment in Progress

2.4. Experimental Analysis

- (1)

- Calibration

- (2)

- Analysis Steps

- (3)

- Instruments and Reagents

3. Methods and Theory

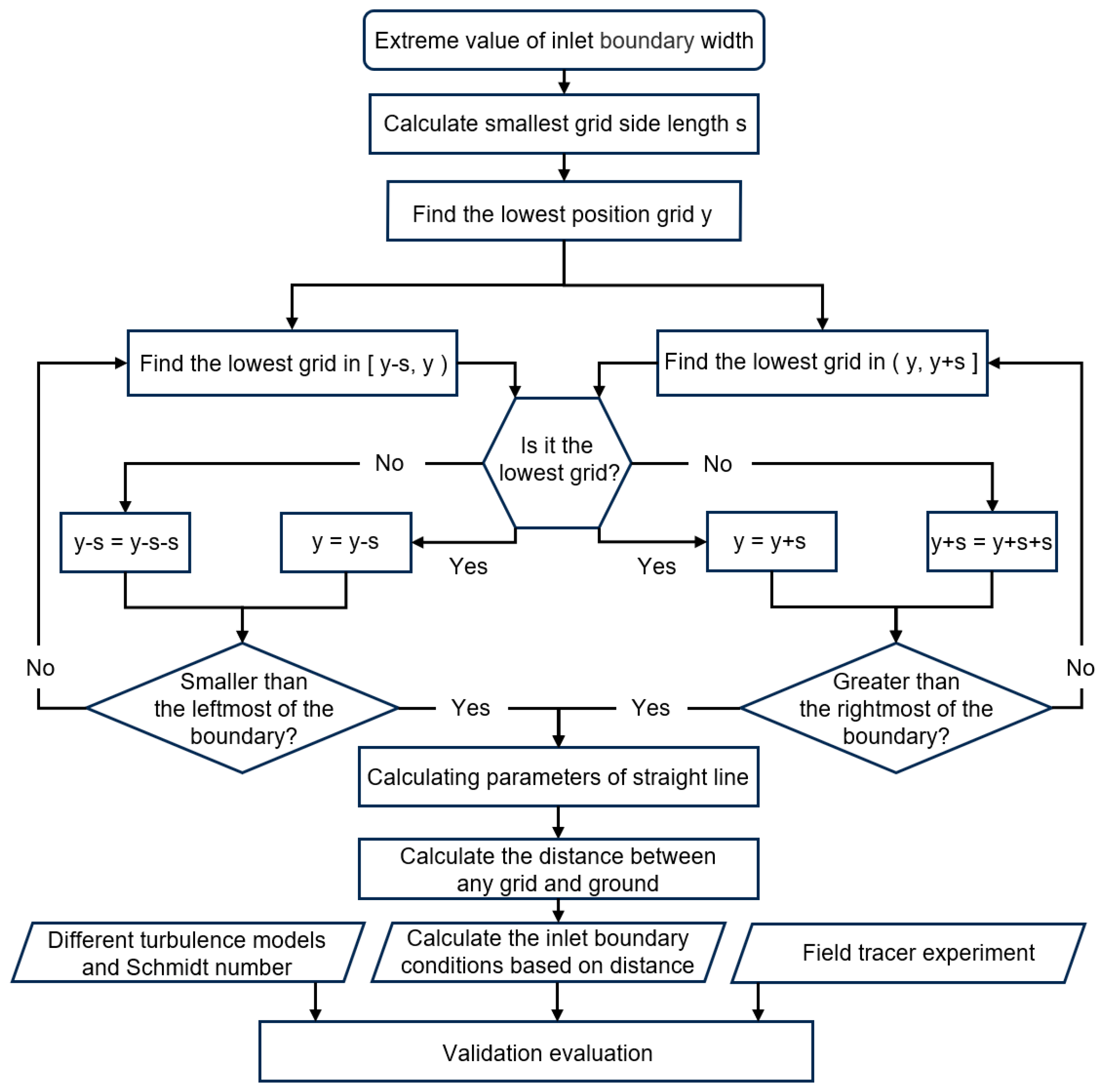

3.1. Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Conditions Based on Uneven Terrain

- (1)

- Preliminary Work

- (2)

- Identify the Lowest Cell

- (3)

- Calculate the Inlet Boundary Conditions

3.2. Governing Equations and Turbulence Modeling

- (a)

- RNG

- (b)

- (c)

- Convection–diffusion

3.3. Model Evaluation

3.4. Dose Calculation

4. Case Setup

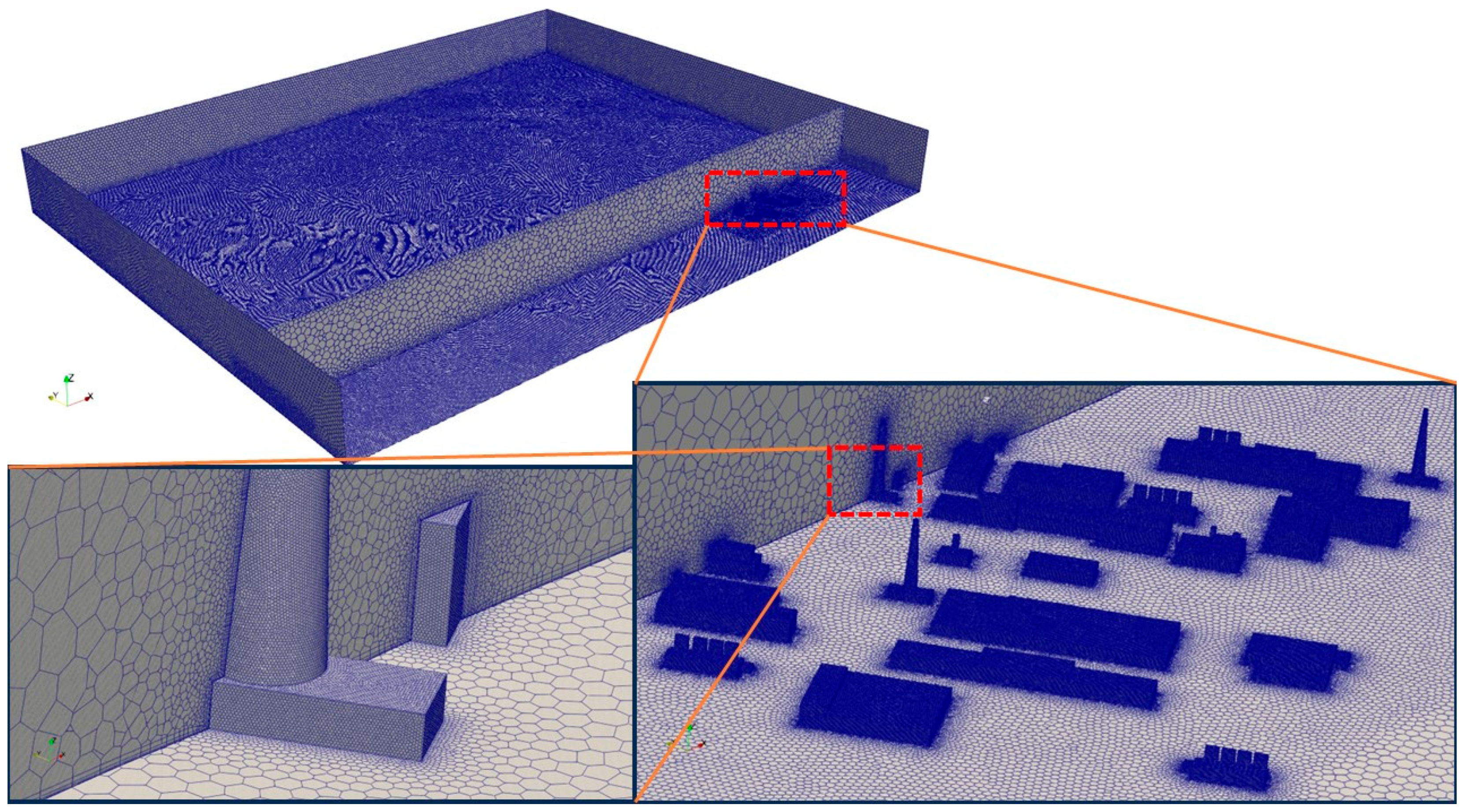

4.1. Computational Domain

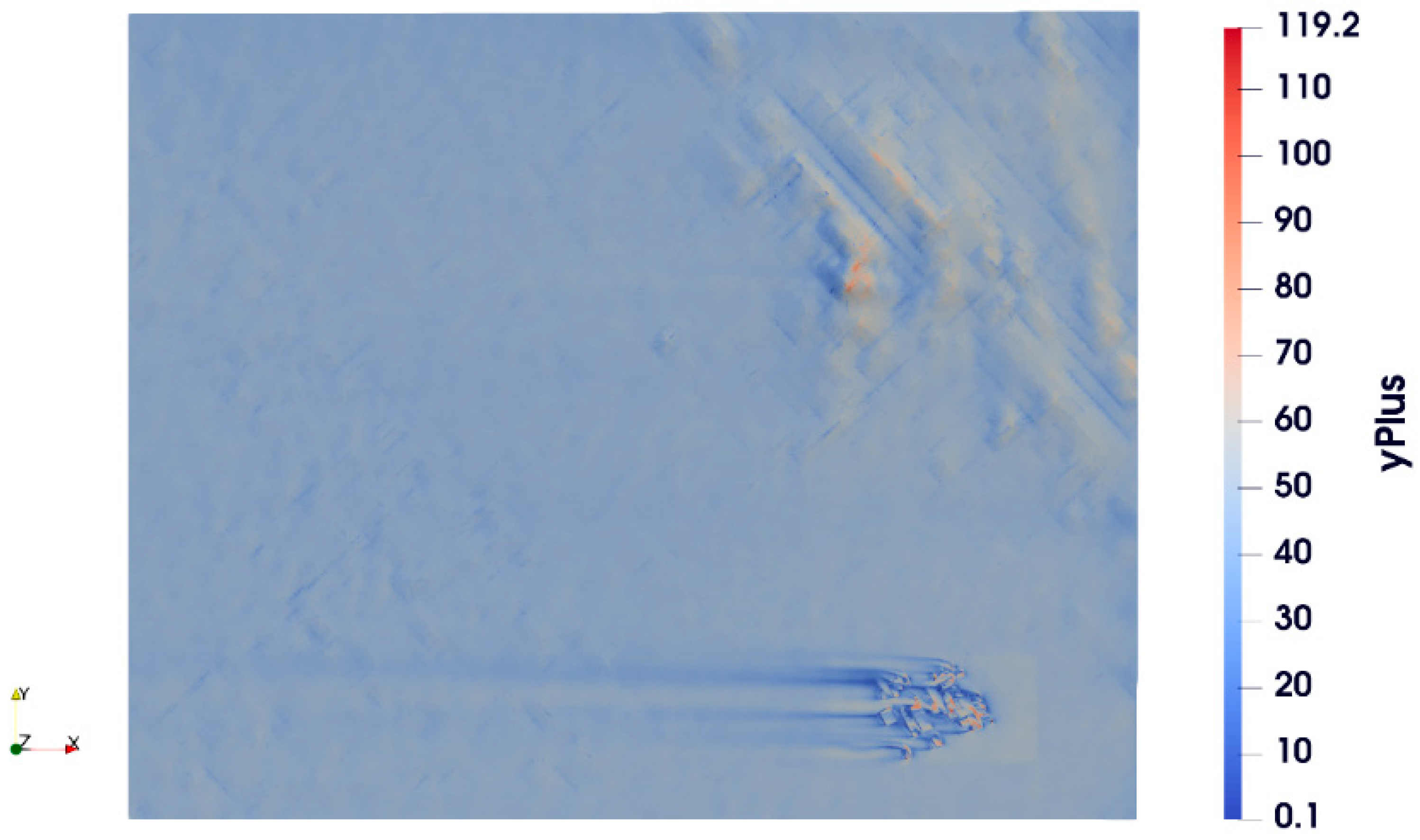

4.2. Mesh Generation and Sensitivity Test

4.3. Simulation Setup

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. SF6 Concentrations of Atmospheric Dispersion Tracer Experiments

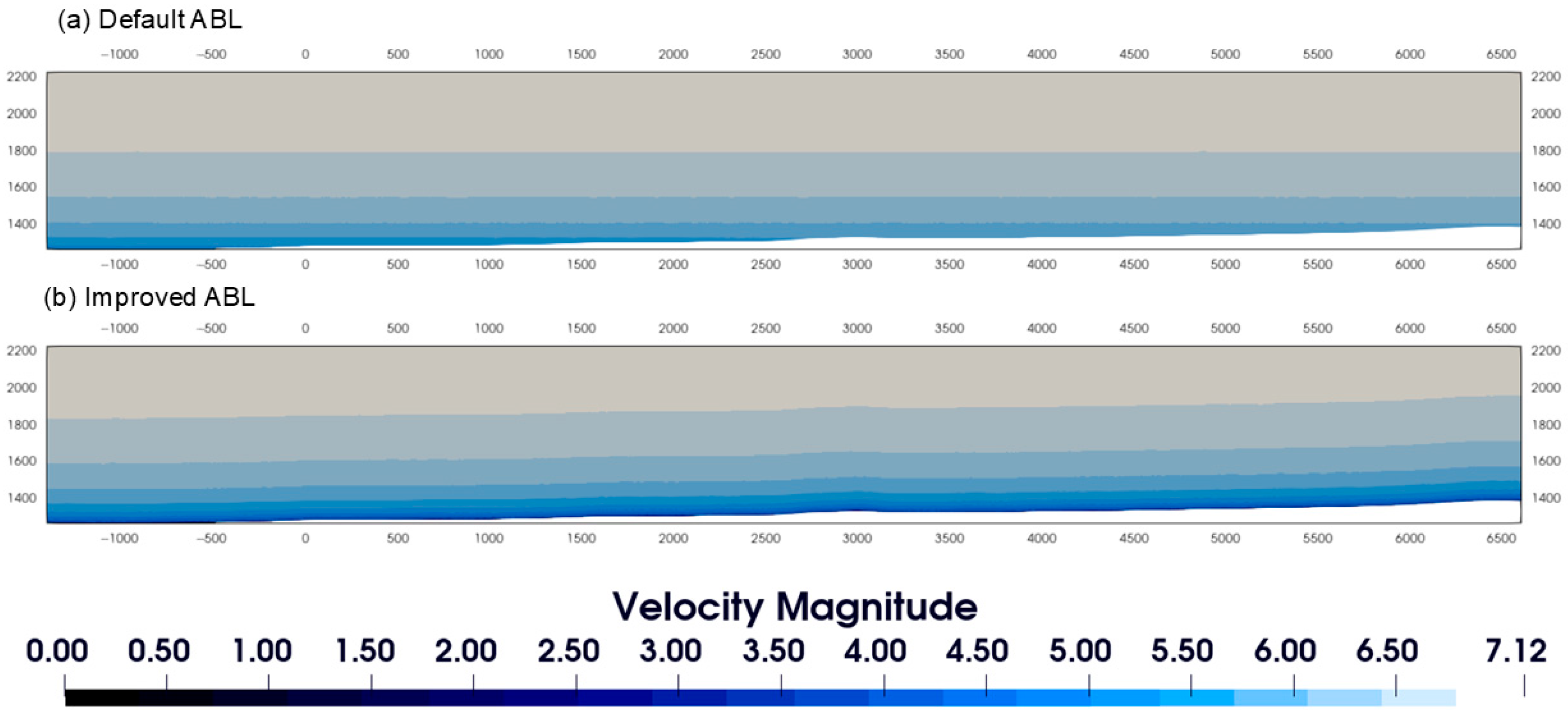

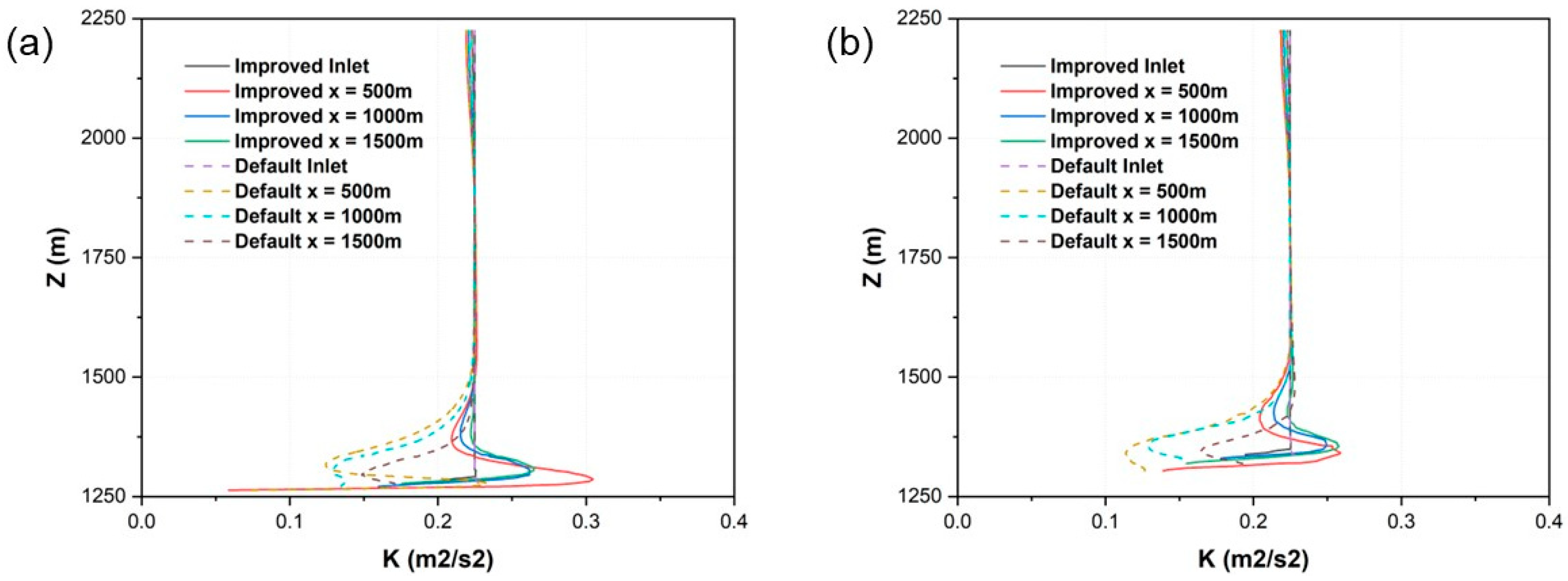

5.2. Comparison of Different Inlet Boundary Conditions

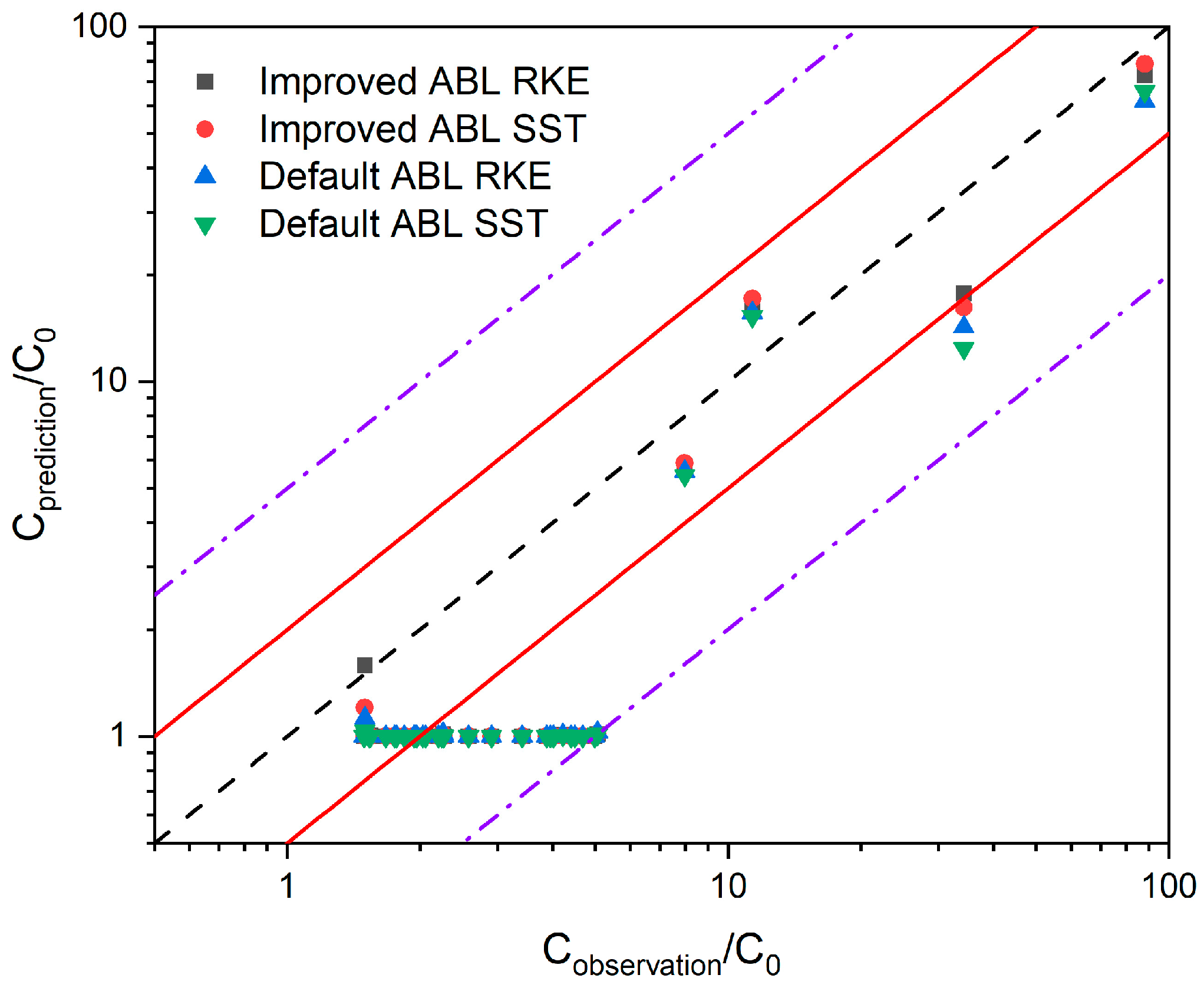

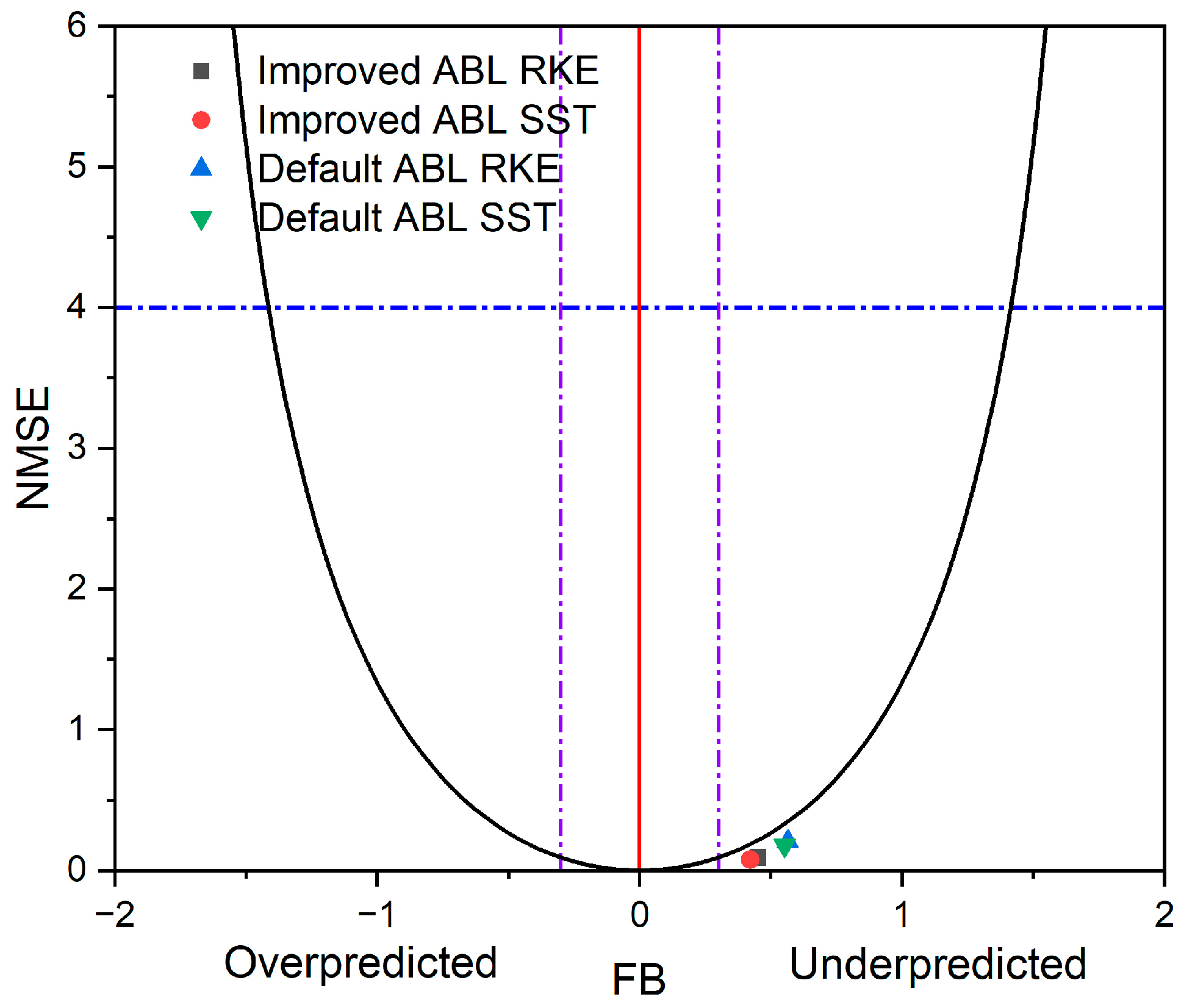

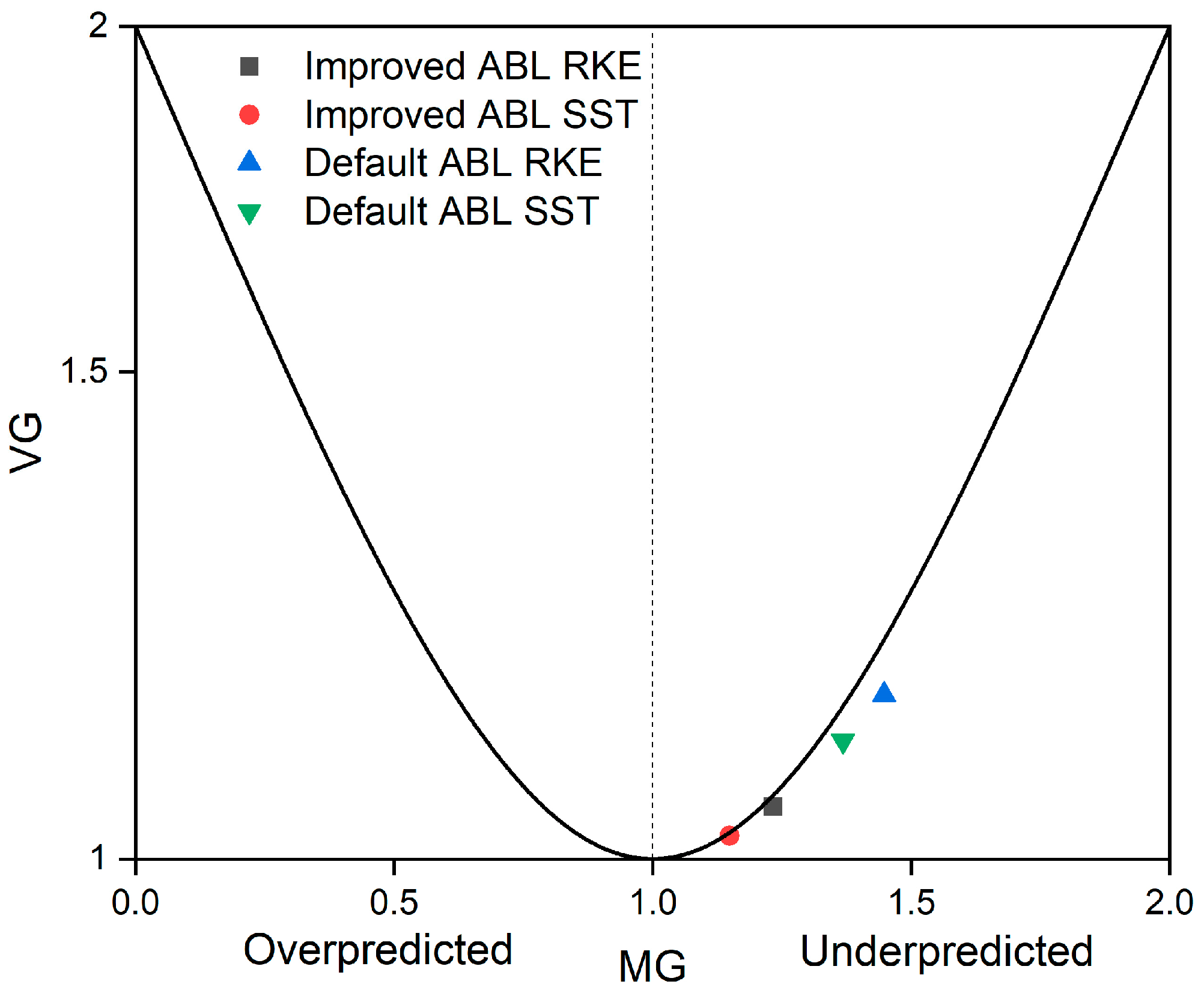

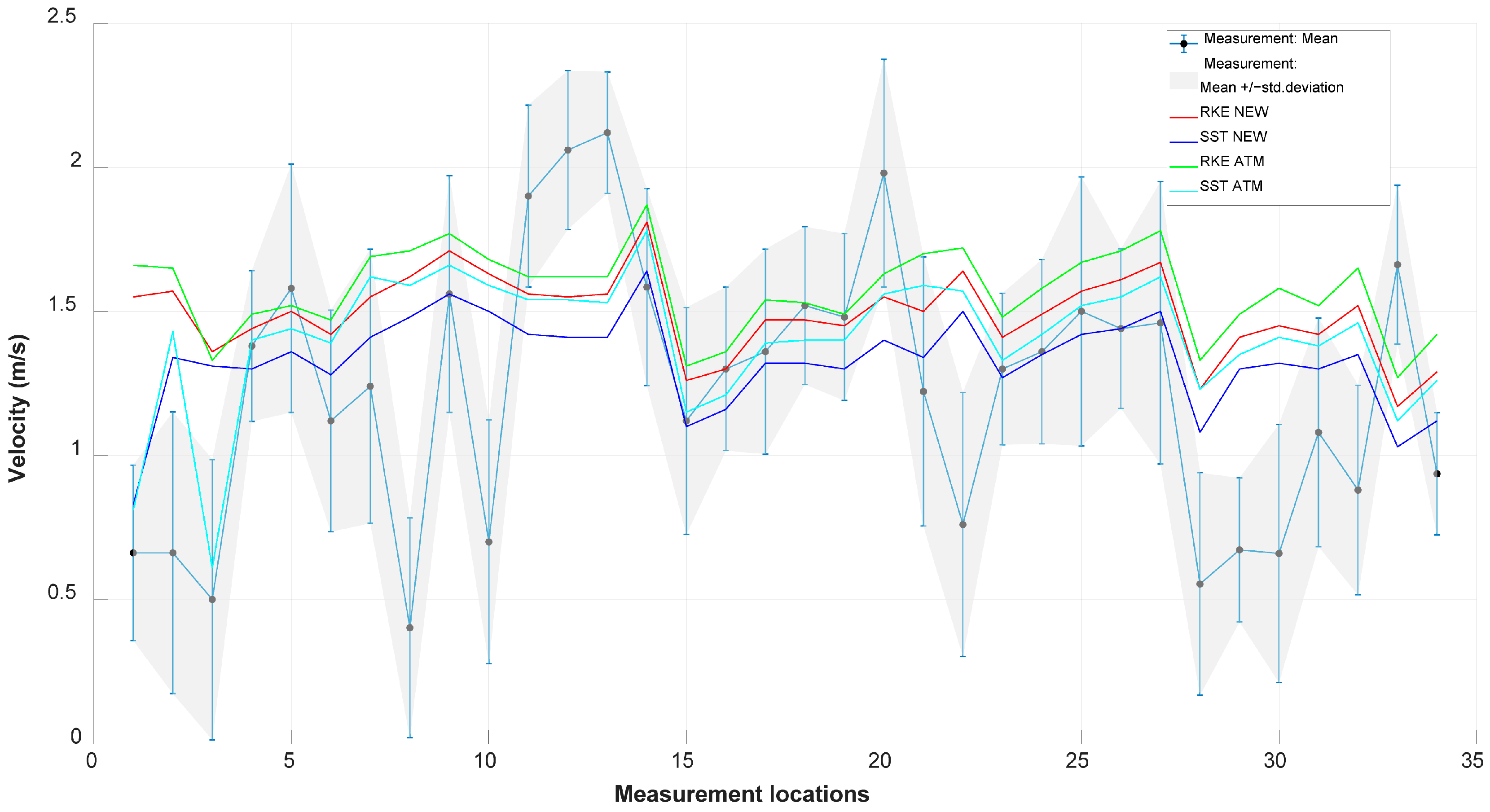

5.3. Comparative Evaluation of Different Simulation Results and SF6 Leakage Experiment

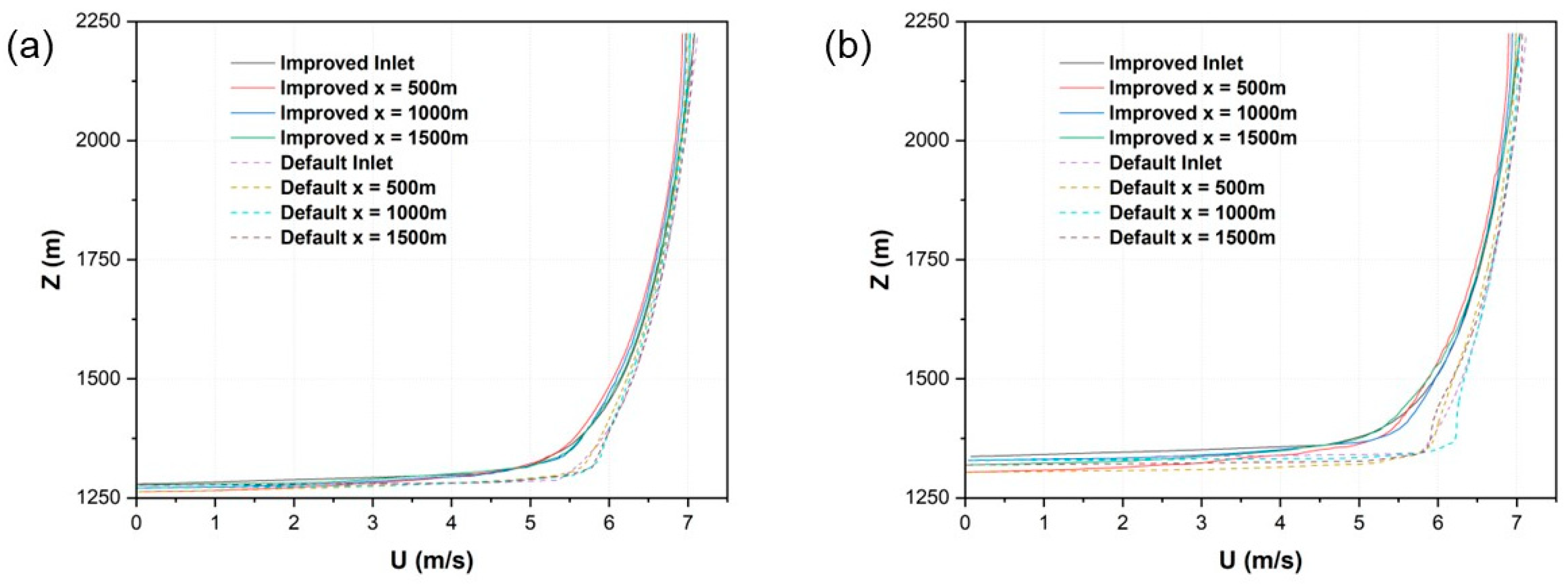

5.4. Velocity and Turbulent Kinetic Energy of the Approaching Boundary Layer

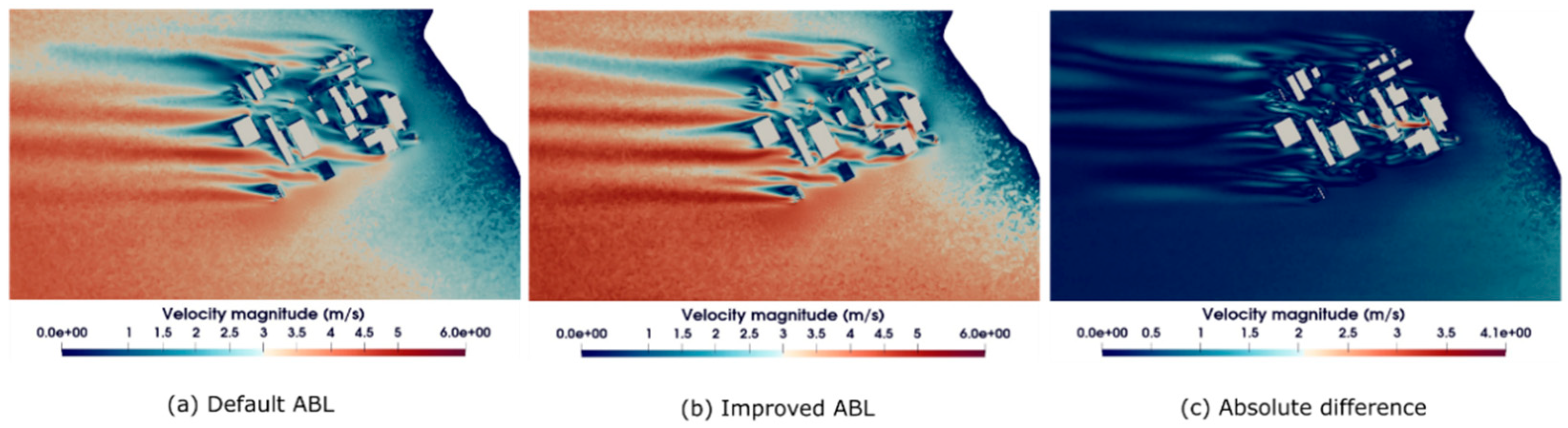

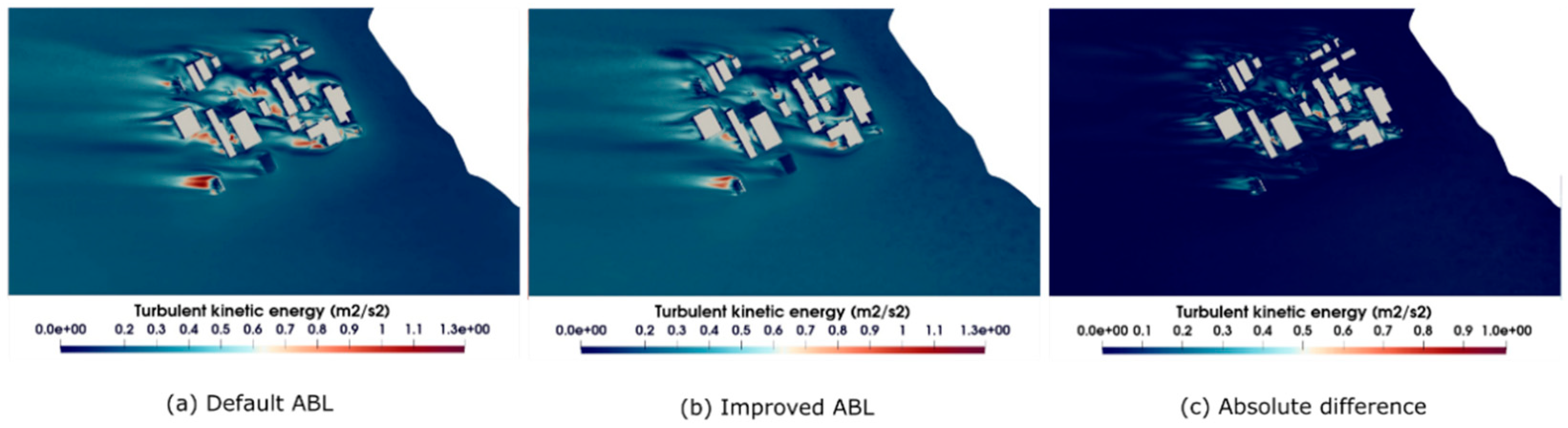

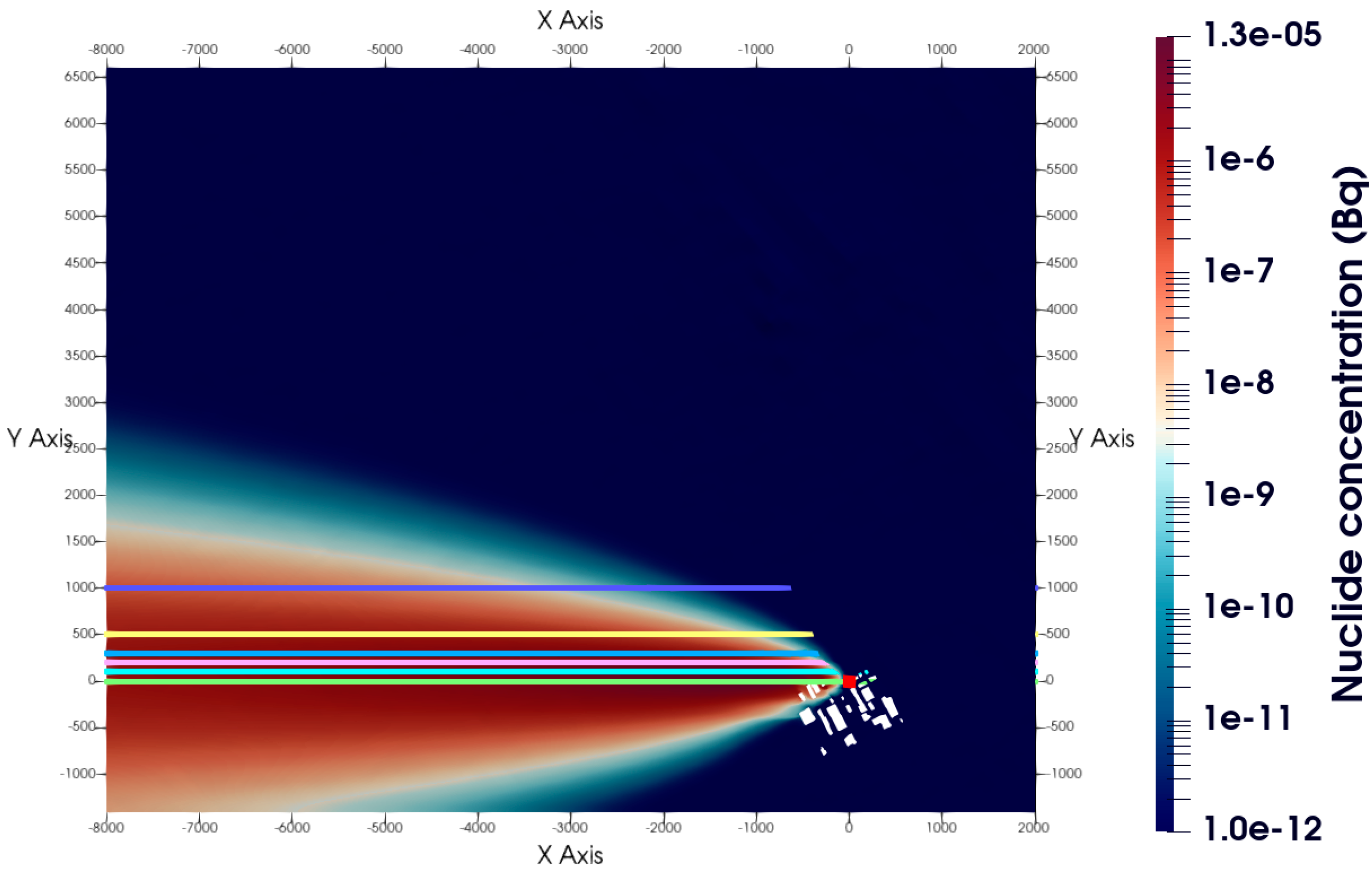

5.5. Comparison of Contours at Height of 10 M from the Ground

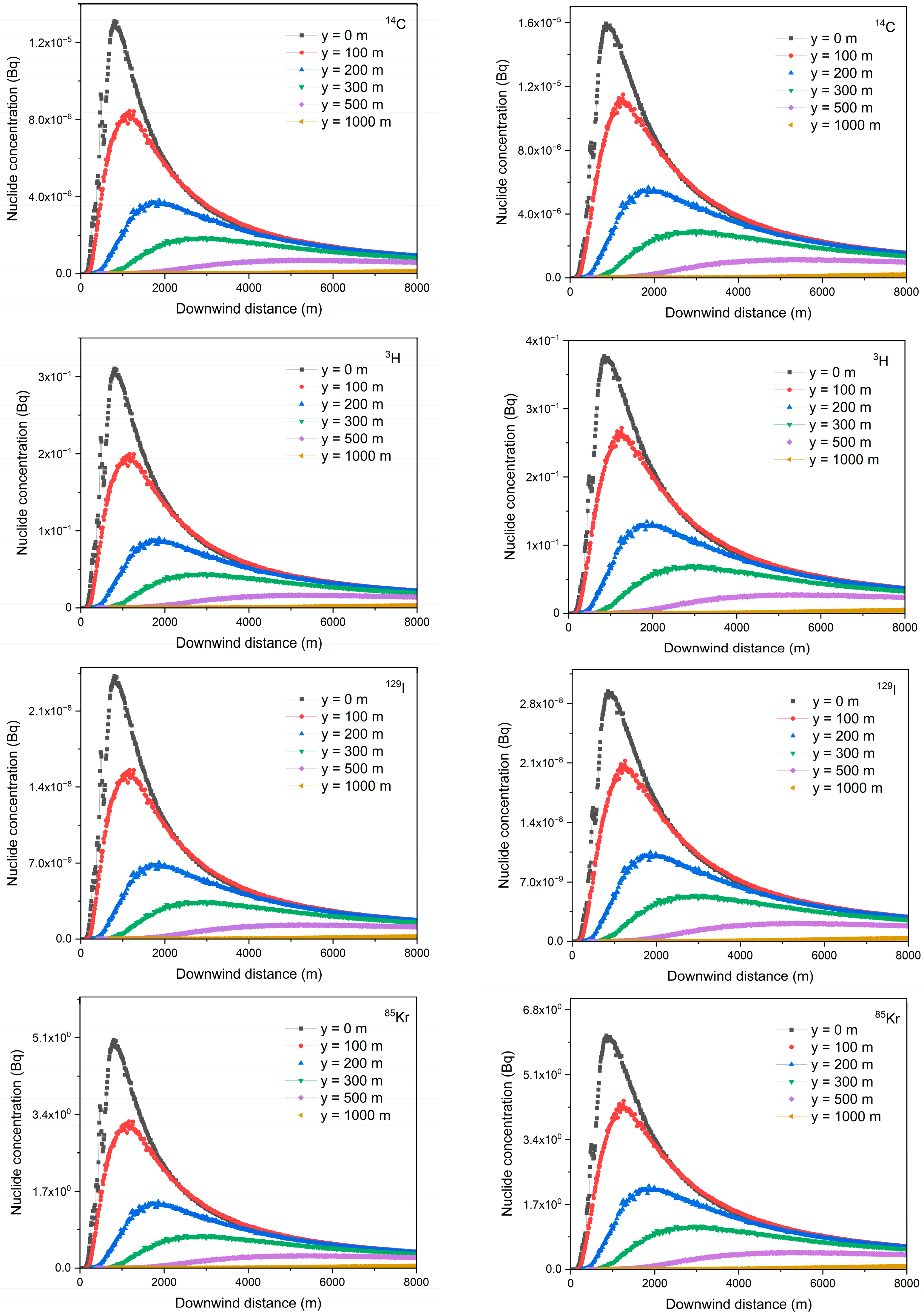

5.6. Comprehensive Evaluation of Pollutant Diffusion Results with Different SCHMIDT Numbers

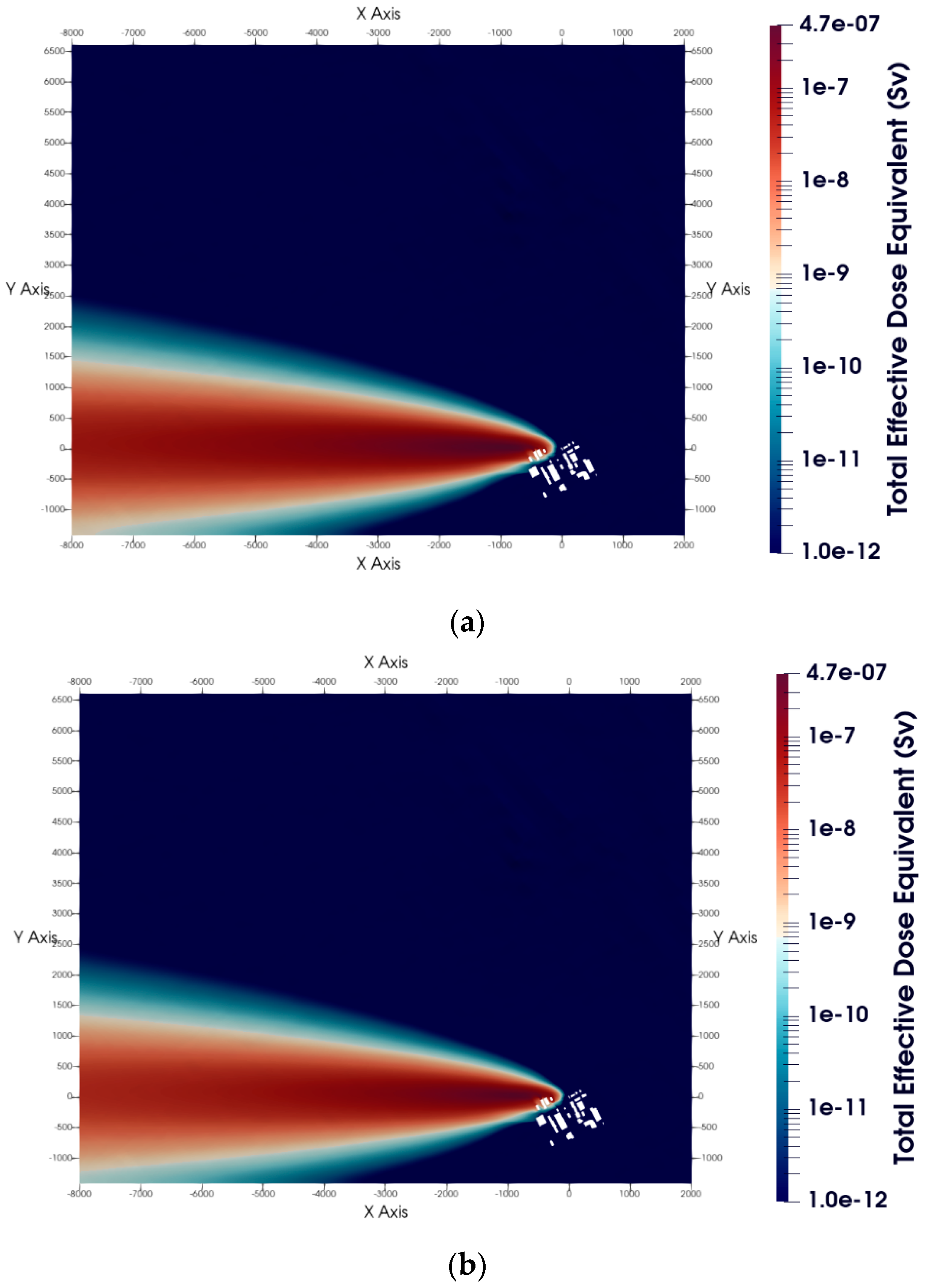

5.7. Radiological Dose Calculations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrell, J. Fukushima Nuclear Disaster: Lethal Levels of Radiation Detected in Leak Seven Years After Plant Meltdown in Japan. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/fukushima-nuclear-disaster-radiation-lethal-levels-leak-japan-tsunami-tokyo-electric-power-company-a8190981.html (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Dai, L.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Cong, T.; Gu, H. The Role of Nuclear Energy in the Carbon Neutrality Goal. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 162, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, H.; Guan, W.; Li, B.; Ullah, S. How Do Nuclear Energy and Stringent Environmental Policies Contribute to Achieving Sustainable Development Targets? Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 3983–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shao, T.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Q. Energy and Sustainable Development Nexus: A Review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 47, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Guo, Q.; Lu, Z. Sensitivity Analysis of Meteorological Parameters to the Airborne Radioactive Materials Diffusion under Normal Operation. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2022, 154, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Yoshie, R. Effect of Atmospheric Stability on Air Pollutant Concentration and Its Generalization for Real and Idealized Urban Block Models Based on Field Observation Data and Wind Tunnel Experiments. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 207, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Huang, Y.; Cui, P.; Wu, J.; Li, M.; Liu, D. Impact of Viaduct on Flow Reversion and Pollutant Dispersion in 2D Urban Street Canyon with Different Roof Shapes—Numerical Simulation and Wind Tunnel Experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-R.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wen, Y.-B.; Tang, Y.-F.; Liu, C.-W.; Zhao, F.-Y. Synoptic Wind Driven Ventilation and Far Field Radionuclides Dispersion across Urban Block Regions: Effects of Street Aspect Ratios and Building Array Skylines. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Yang, F.; Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, R. Numerical Simulation and Wind Tunnel Experiments on the Effect of a Cubic Building on the Flow and Pollutant Diffusion under Stable Stratification. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Yu, C.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Qu, S. Numerical Simulation of LNG Release and Dispersion Using a Multiphase CFD Model. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2018, 56, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Xiang, W.; Han, Z.; Xiao, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Yan, P.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Validation of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics Emergency Response Model with the Meteorological Towers Measurements and SF6 Diffusion and Pool Fire Experiments. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 81, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhao, P.; Wang, R.; Yao, R.; Hu, J. Numerical Simulations of the Flow Field and Pollutant Dispersion in an Idealized Urban Area under Different Atmospheric Stability Conditions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 136, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.T. Modelling Street-Scale Flow and Dispersion in Realistic Winds-Towards Coupling with Mesoscale Meteorological Models. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2011, 141, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, L.; Ma, Y. An Integrated Risk Assessment Method for Urban Areas Due to Chemical Leakage Accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 247, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, J. Numerical Study on the Gaseous Radioactive Pollutant Dispersion in Urban Area from the Upstream Wind: Impact of the Urban Morphology. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Xue, N.; Liu, X. Research on the Influence of Complex Terrain on Atmospheric Dispersion After Accident. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Nuclear Engineering, London, UK, 22–26 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kocijan, J.; Hvala, N.; Perne, M.; Mlakar, P.; Grašič, B.; Božnar, M.Z. Surrogate Modelling for the Forecast of Seveso-Type Atmospheric Pollutant Dispersion. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M.A.; Soner, M.A.M.; Khanom, S.; Uddin, M.J.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Chowdhury, M.S.H.; Helal, A.; Khaer, M.A.; Hassan, S.M.T.; Chowdhury, M.T.; et al. Assessment of Radiation Dose Associated with the Atmospheric Release of 41Ar from the TRIGA Mark-II Research Reactor in Bangladesh. Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install. 2024, 2024, 9141535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, J.; Ge, D.; Chen, C.; Chen, L. Oceanic Radionuclide Dispersion Method Investigation for Nonfixed Source from Marine Reactor Accident. Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install. 2022, 2022, 2822857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.; Coburn, M.; Cox, S.J.; Bulot, F.M.J.; Xie, Z.T.; Vanderwel, C. Comparing Large-Eddy Simulation and Gaussian Plume Model to Sensor Measurements of an Urban Smoke Plume. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, P.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, F. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Dispersion of Carbon Dioxide Plume. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 256, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, A.; Kalkman, I.; Blocken, B.; Burlando, M.; Repetto, M.P. Impact of Turbulence Models and Roughness Height in 3D Steady RANS Simulations of Wind Flow in an Urban Environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Turbulent Flows; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780521598866. [Google Scholar]

- Blocken, B. Computational Fluid Dynamics for Urban Physics: Importance, Scales, Possibilities, Limitations and Ten Tips and Tricks towards Accurate and Reliable Simulations. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.W. A Numerical Study of Three-Dimensional Turbulent Channel Flow at Large Reynolds Numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 1970, 41, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-T.; Castro, I.P. Efficient Generation of Inflow Conditions for Large Eddy Simulation of Street-Scale Flows. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2008, 81, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, R.; Gibbs, J.A.; Salesky, S.T.; Anderson, W.; Calaf, M.; Stoll, R.; Gibbs, J.A.; Salesky, S.T.; Anderson, W.; Calaf, M. Review: Large-Eddy Simulation of the Atmospheric Boundary Layer. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2020, 177, 541–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B. LES over RANS in Building Simulation for Outdoor and Indoor Applications: A Foregone Conclusion? Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 821–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yan, T. A Reasonable Inlet Boundary for Wind Simulation Based on a Trivariate Joint Distribution Model. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 233, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, S. Simulating Microscale Urban Airflow and Pollutant Distributions Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics Model: A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhao, P.; Yang, G.; Yu, H.; He, F.; He, B. Study on Flow Field Simulation at Transmission Towers in Loess Hilly Regions Based on Circular Boundary Constraints. Energy Eng. J. Assoc. Energy Eng. 2023, 120, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Stoellinger, M.K. RANS Simulations of Neutral Atmospheric Boundary Layer Flow over Complex Terrain with Comparisons to Field Measurements. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Salazar, A.A.; Peng, S.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L. A Multi-Scale Model for Day-Ahead Wind Speed Forecasting: A Case Study of the Houhoku Wind Farm, Japan. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Xu, F.; Wang, L. A Study on the Gaseous Radionuclide Dispersion in the Highway across Urban Blocks: Effects of the Urban Morphology, Roadside Vegetation and Leakage Location. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Dang, W.; Yan, X.; Yu, J.; Bai, Y. Dispersion Characteristics and Hazard Area Prediction of Mixed Natural Gas Based on Wind Tunnel Experiments and Risk Theory. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 152, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, H.; Lin, G.; Dang, W.; Yu, A.; Zhang, J.; Gu, M.; Ge, C. Measurements and Predictions of Harmful Releases of the Gathering Station over the Mountainous Terrain. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 71, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Cai, J.; Reniers, G.; Yang, M.; Chen, C.; Wu, J. Safety Barrier Performance Assessment by Integrating Computational Fluid Dynamics and Evacuation Modeling for Toxic Gas Leakage Scenarios. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, M.; Vanderwel, C.; Herring, S.; Xie, Z.T. Impact of Local Terrain Features on Urban Airflow. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2023, 189, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ooka, R.; Kikumoto, H.; Sato, T.; Arai, M. CFD Simulations on High-Buoyancy Gas Dispersion in the Wake of an Isolated Cubic Building Using Steady RANS Model and LES. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ooka, R.; Kikumoto, H.; Jia, H. Eulerian RANS Simulations of Near-Field Pollutant Dispersion around Buildings Using Concentration Diffusivity Limiter with Travel Time. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, N.; Chen, Q. Generalizability Evaluation of K-ε Models Calibrated by Using Ensemble Kalman Filtering for Urban Airflow and Airborne Contaminant Dispersion. Build. Environ. 2022, 212, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roetzer, H.; Riesing, J. Measurement of the Contribution of a Single Plant to Air Pollution Using the SF6-Tracer Technique; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 1996; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Petersson, K.F.; Shallcross, D.E. The Use of Cyclic Perfluoroalkanes and SF 6 in Atmospheric Dispersion Experiments. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 2047–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, J.E. Investigation of Atmospheric Dispersion in an Urban Environment Using SF 6 Tracer and Numerical Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Connan, O.; Leroy, C.; Derkx, F.; Maro, D.; Hébert, D.; Roupsard, P.; Rozet, M. Atmospheric Dispersion of an Elevated Release in a Rural Environment: Comparison between Field SF6 Tracer Measurements and Computations of Briggs and ADMS Models. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 7174–7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.P.; Gryning, S.E.; Hasager, C.B.; Courtney, M. General Rights Extending the Wind Profile Much Higher than the Surface Layer. In Proceedings of the 2009 European Wind Energy Conference and Exhibition, Marseille, France, 16–19 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Li, Y.; Cai, C.S.; Liao, H.; Xu, G.J. Numerical Simulation of the Neutral Equilibrium Atmospheric Boundary Layer Using the SST K-ω Turbulence Model. Wind Struct. Int. J. 2013, 17, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Cai, S.C.S.; Xu, X. Numerical Simulations of the Mean Wind Speeds and Turbulence Intensities over Simplified Gorges Using the SST K-ω Turbulence Model. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2016, 10, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFOAM OpenFOAM: User Guide V2012 the Open Source CFD Toolbox. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/guides/v2012/doc/guide-bcs-inlet-atm-atmBoundaryLayer.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Shih, T.H.; Liou, W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A New K-ϵ Eddy Viscosity Model for High Reynolds Number Turbulent Flows. Comput. Fluids 1994, 24, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromke, C.; Blocken, B. Influence of Avenue-Trees on Air Quality at the Urban Neighborhood Scale. Part I: Quality Assurance Studies and Turbulent Schmidt Number Analysis for RANS CFD Simulations. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 196, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, H.; Sharma, A.; Gairola, A. A Review on the Study of Urban Wind at the Pedestrian Level around Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 18, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Druenen, T.; van Hooff, T.; Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B. CFD Evaluation of Building Geometry Modifications to Reduce Pedestrian-Level Wind Speed. Build. Environ. 2019, 163, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, M.; Tominaga, Y. Multi-Fidelity Shape Optimization Methodology for Pedestrian-Level Wind Environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-S.; Su, Y.-M.; Wen, C.-Y.; Juan, Y.-H.; Wang, W.-S.; Cheng, C.-H. Estimation of Wind Power Generation in Dense Urban Area. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, Y.; Stathopoulos, T. Turbulent Schmidt Numbers for CFD Analysis with Various Types of Flowfield. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 8091–8099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R.; Strimaitis, D.G.; Scire, J.S.; Moore, G.E.; Kessler, R.C. Overview of Results of Analysis of Data from the South-Central Coast Cooperative Aerometric Monitoring Program (SCCCAMP 1985). J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1991, 30, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R.; Chang, J.C.; Strimaitis, D.G. Hazardous Gas Model Evaluation with Field Observations. Atmos. Environ. Part A Gen. Top. 1993, 27, 2265–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R. Air Quality Model Evaluation and Uncertainty. JAPCA 1988, 38, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R. Uncertainties in Air Quality Model Predictions. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 1993, 62, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S. Confidence Limits for Air Quality Model Evaluations as Estimated by Bootstrap and Jackknife Resampling Methods. Atmos. Environ. 1989, 23, 1385–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, M.B.; Dewji, S.A.; Leggett, R.W.; Hiller, M.; Veinot, K.; Manger, R.P.; Eckerman, K.F.; Ryman, J.C.; Easterly, C.E.; Hertel, N.E.; et al. External Exposure to Radionuclides in Air, Water, and Soil; USA Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Ma, J.; Ma, J.L.; Li, R. Environmental Assessment and Analysis on the Siting Stage of Spent Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Plant. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2015, 35, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- USGS Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Database. Available online: https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/SRTM (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Franke, J.; Hellsten, A.; Schlünzen, H.; Carissimo, B. The COST 732 Best Practice Guideline for CFD Simulation of Flows in the Urban Environment: A Summary. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 44, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, Y.; Mochida, A.; Yoshie, R.; Kataoka, H.; Nozu, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Shirasawa, T. AIJ Guidelines for Practical Applications of CFD to Pedestrian Wind Environment around Buildings. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2008, 96, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, J. Recommendations of the COST Action C14 on the Use of CFD in Predicting Pedestrian Wind Environment. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Computational Wind Engineering, Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 July 2006; pp. 529–532. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Zidan, Y.; Mendis, P.; Gunawardena, T. Optimising the Computational Domain Size in CFD Simulations of Tall Buildings. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, H.G.; Tabor, G.; Jasak, H.; Fureby, C. A Tensorial Approach to Computational Continuum Mechanics Using Object-Oriented Techniques. Comput. Phys. 1998, 12, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibas, L.; Stolfi, J. Primitives for the Manipulation of General Subdivisions and the Computation of Voronoi. ACM Trans. Graph. 1985, 4, 74–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.T.; Schachter, B.J. Two Algorithms for Constructing a Delaunay Triangulation. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 1980, 9, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.L. Software for c1 surface interpolation. In Mathematical Software; John, R.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; pp. 161–194. ISBN 978-0-12-587260-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surfer Help Triangulation with Linear Interpolation. Available online: https://surferhelp.goldensoftware.com/griddata/idd_grid_data_triangulation.htm (accessed on 7 April 2024).

| Parameter | Default ABL | Improved ABL |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclides | Half-Life (Year) | Inhalation Dose Conversion Factor (Sv·m3/Bq·s) | Air Submersion Dose Rate Coefficient (Sv·m3/Bq·s) | Activity (Bq/Year) | Breathing Rate (m3/Day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 12.35 | 1.80 × 10−11 | 3.80 × 10−20 | 4.09 × 1015 | 19.2 |

| 14 | 5730 | 6.20 × 10−12 | 3.86 × 10−17 | 1.86 × 1011 | 19.2 |

| 85 | 10.73 | - | 6.67 × 10−16 | 6.66 × 1016 | 19.2 |

| 129 | 1.6 × 107 | 9.60 × 10−8 | 2.54 × 10−16 | 3.31 × 108 | 19.2 |

| Parameter | Uh= 100 m m/s | Z0 m | q m3/s | Cgas ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 5.66 | 0.013 |

| Model | ABL | FB | MG | VG | NSME | FAC2 | FAC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RKE | Improved | 0.4519 | 1.2325 | 1.0447 | 0.0928 | 0.4412 | 1 |

| SST | Improved | 0.4223 | 1.1488 | 1.0194 | 0.0772 | 0.4118 | 1 |

| RKE | Default | 0.5647 | 1.4476 | 1.1466 | 0.2053 | 0.4118 | 1 |

| SST | Default | 0.5524 | 1.3681 | 1.1032 | 0.1763 | 0.4118 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Ding, D.; Dou, X.; Li, Z. Effects of Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Boundary Conditions for Uneven Terrain on Pollutant Dispersion from Nuclear Facilities. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101203

Wang Z, Ding D, Dou X, Li Z. Effects of Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Boundary Conditions for Uneven Terrain on Pollutant Dispersion from Nuclear Facilities. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(10):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101203

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhongkun, Dexin Ding, Xiumin Dou, and Zhengming Li. 2025. "Effects of Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Boundary Conditions for Uneven Terrain on Pollutant Dispersion from Nuclear Facilities" Atmosphere 16, no. 10: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101203

APA StyleWang, Z., Ding, D., Dou, X., & Li, Z. (2025). Effects of Improved Atmospheric Boundary Layer Inlet Boundary Conditions for Uneven Terrain on Pollutant Dispersion from Nuclear Facilities. Atmosphere, 16(10), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16101203