Exposure to Wildfires Exposures and Mental Health Problems among Firefighters: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

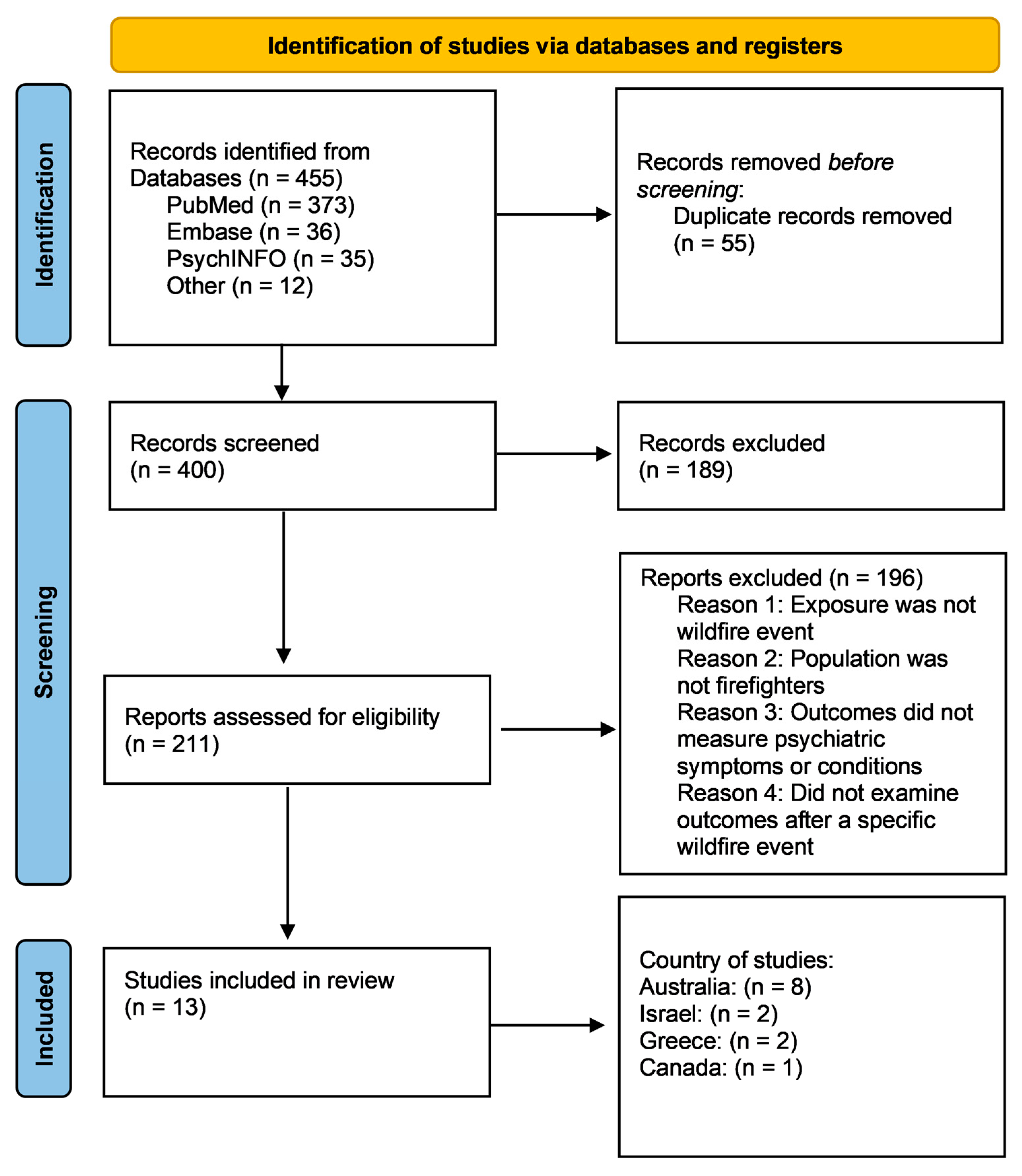

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Search and Selection Results

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Individual Wildfire Events and Study Findings

3.4.1. Israel

3.4.2. Canada

3.4.3. Greece

3.4.4. Australia

| Author, Title | Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amster et al. (2018) [19], Occupational Exposures and Psychological Symptoms Among Firefighters and Police During a Major Wildfire: The Carmel Cohort Study. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| Leykin et al. (2013) [14], Posttraumatic Symptoms and Posttraumatic Growth of Israeli Firefighters, at One Month following the Carmel Fire Disaster. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| Cherry et al. (2021) [9], Prevalence of Mental Ill-Health in a Cohort of First Responders Attending the Fort McMurray Fire. | Low | Low | Low |

| Theleritis et al. (2020) [18], Coping and Its Relation to PTSD in Greek Firefighters. | Low | Low | Low |

| Psarros et al. (2018) [17], Personality characteristics and individual factors associated with PTSD in firefighters one month after extended wildfires. | Low | Low | Low |

| Doley et al. (2016) [16], An Investigation Into the Relationship Between Long-term Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Coping in Australian Volunteer Firefighters. | Low | Low | Low |

| McFarlane (1986) [25], Long-term psychiatric morbidity after a natural disaster. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| McFarlane et al. (1987) [23], Life events and psychiatric disorder: the role of a natural disaster. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| McFarlane et al. (1988) [21], The longitudinal course of posttraumatic morbidity. The range of outcomes and their predictors. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| McFarlane et al. (1988) [24], The aetiology of posttraumatic stress disorders following a natural disaster. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| McFarlane et al. (1988) [26], Relationship between psychiatric impairment and a natural disaster: the role of distress. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| McFarlane (1989) [22], The aetiology of posttraumatic morbidity: Predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors. | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| Smith et al. (2020) [15], Supporting Volunteer Firefighter Well-Being: Lessons from the Australian “Black Summer” Bushfires. | Low | Low | Very low |

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk Factors

4.2. Longitudinal Outcomes (PTSD Time Frame and Health Outcomes)

4.3. Potential Mechanisms

4.4. Gaps in Disaster Research: Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Fahy, R.; Evarts, B.; Stein, G. US Fire Department Profile 2020; National Fireprotection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. WILDLAND FIRE Federal Agencies Face Barriers to Recruiting and Retaining Firefighters. 2023. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-106888#:~:text=The%20barriers%20GAO%20found%20were,(7)%20hiring%20process%20challenges (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Wolkow, A.P.; Barger, L.K.; O’Brien, C.S.; Sullivan, J.P.; Qadri, S.; Lockley, S.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W. Associations between Sleep Disturbances, Mental Health Outcomes and Burnout in Firefighters, and the Mediating Role of Sleep during Overnight Work: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Sleep. Res. 2019, 28, e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.; Duncan, R. Special Report: Wildland Firefighters—Hidden Heroes of the Mental Health Effects of Climate Change. Psychiatr. News 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Climate Change Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Wildfire Climate Connection. Available online: https://www.noaa.gov/noaa-wildfire/wildfire-climate-connection (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Wehner, M.F.; Arnold, J.R.; Knutson, T.; Kunkel, K.E.; LeGrande, A.N. Ch. 8: Droughts, Floods, and Wildfires. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. What Is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Cherry, N.; Galarneau, J.M.; Melnyk, A.; Patten, S. Prevalence of Mental Ill-Health in a Cohort of First Responders Attending the Fort McMurray Fire. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 66, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Gai, A.R.; Joiner, T.E. Wildland Firefighters and Suicide Risk: Examining the Role of Social Disconnectedness. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 266, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Siemieniuk, R. What Is GRADE? Available online: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/us/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Brozek, J.L.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bowen, J.M.; Bucher, J.; Chiu, W.A.; Cronin, M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falavigna, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 30: The GRADE Approach to Assessing the Certainty of Modeled Evidence—An Overview in the Context of Health Decision-Making. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 129, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leykin, D.; Lahad, M.; Bonneh, N. Posttraumatic Symptoms and Posttraumatic Growth of Israeli Firefighters, at One Month Following the Carmel Fire Disaster. Psychiatry J. 2013, 2013, 274121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Holmes, L.; Larkin, B.; Mills, B.; Dobson, M. Supporting Volunteer Firefighter Well-Being: Lessons from the Australian Black Summer Bushfires. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2022, 37, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doley, R.M.; Bell, R.; Watt, B.D. An Investigation into the Relationship between Long-Term Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Coping in Australian Volunteer Firefighters. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarros, C.; Theleritis, C.; Kokras, N.; Lyrakos, D.; Koborozos, A.; Kakabakou, O.; Tzanoulinos, G.; Katsiki, P.; Bergiannaki, J.D. Personality Characteristics and Individual Factors Associated with PTSD in Firefighters One Month after Extended Wildfires. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2018, 72, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theleritis, C.; Psarros, C.; Mantonakis, L.; Roukas, D.; Papaioannou, A.; Paparrigopoulos, T.; Bergiannaki, J.D. Coping and Its Relation to PTSD in Greek Firefighters. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amster, E.; Fertig, S.; Green, M.; Carel, R. 589 Occupational Exposures and Psychological Symptoms among Fire Fighters and Police during a Major Wildfire: The Carmel Cohort Study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 75 (Suppl. 2), A590–A591. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, L. Growth After Trauma: Why Are Some People More Resilient than Others- and Can It Be Taught? Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2016, 47, 48. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, A.C. The Longitudinal Course of Posttraumatic Morbidity The Range of Outcomes and Their Predictors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1988, 176, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.C. The Aetiology of Post-Traumatic Morbidity: Predisposing, Precipitating and Perpetuating Factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 1989, 154, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.C. Life Events and Psychiatric Disorder: The Role of a Natural Disaster. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 151, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.C. The Aetiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders Following a Natural Disaster. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 152, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.C. Long-Term Psychiatric Morbidity after a Natural Disaster. Implications for Disaster Planners and Emergency Services. Med. J. Aust. 1986, 145, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcfarlane, A.C. Relationship between Psychiatric Impairment and a Natural Disaster: The Role of Distress. Psychol. Med. 1988, 18, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Fire Management Victoria. Ash Wednesday 1983. Available online: https://www.ffm.vic.gov.au/history-and-incidents/ash-wednesday-1983 (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- County Fire Authority. Ash Wednesday. 1983. Available online: https://www.cfa.vic.gov.au/about-us/history-major-fires/major-fires/ash-wednesday-1983#:~:text=2023%20marks%20the%2040th%20anniversary,involved%20in%20the%20response%20efforts (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Lewis-Schroeder, N.F.; Kieran, K.; Murphy, B.L.; Wolff, J.D.; Robinson, M.A.; Kaufman, M.L. Conceptualization, Assessment, and Treatment of Traumatic Stress in First Responders: A Review of Critical Issues. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Volunteer Fire Service Council (NVFC). Volunteer Fire Service Fact Sheet; The National Volunteer Fire Service Council (NVFC): Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, M.L.; Cardenas, M.; Nesbitt, K.; Coe, E.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Zimering, R.T.; Gulliver, S.B. Career Versus Volunteer Firefighters: Differences in Perceived Availability and Barriers to Behavioral Health Care. Psychol. Serv. 2022, 19, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, I.H.; Boffa, J.W.; Hom, M.A.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Joiner, T.E. Differences in Psychiatric Symptoms and Barriers to Mental Health Care between Volunteer and Career Firefighters. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 247, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America Men’s Mental Health. Available online: https://adaa.org/find-help/by-demographics/mens-mental-health (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 0-89042-575-2. [Google Scholar]

- Frommberger, U.; Frommberger, H.; Maercker, A. Delayed Onset of PTSD—A Problem for Diagnosis and Litigation—With Special Reference to Political Imprisonment in the GDR. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2020, 70, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Chronic Stress Puts Your Health at Risk; Mayo Clinic: Arizona, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vancheri, F.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, E.; Henein, M.Y. Mental Stress and Cardiovascular Health—Part I. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Petrillo, J.T. Fatal Firefighter Injuries in the United States. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/nfpa-research/fire-statistical-reports/fatal-firefighter-injuries (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- McEwen, B.S. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress. 2017, 1, 2470547017692328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.; Dhikav, V. Hippocampus in Health and Disease: An Overview. Ann. Indian. Acad. Neurol. 2012, 15, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.; Sansing, L.H.; Arnsten, A.F.T.; Datta, D. Chronic Stress Weakens Connectivity in the Prefrontal Cortex: Architectural and Molecular Changes. Chronic Stress 2021, 5, 24705470211029254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate.gov. Staff Quantifying Sulfur Dioxide Emissions and Understanding Air Quality Impacts from Wildfires. Available online: https://cpo.noaa.gov/ (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Borroni, E.; Pesatori, A.C.; Bollati, V.; Buoli, M.; Carugno, M. Air Pollution Exposure and Depression: A Comprehensive Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H.; Hino, K.; Ito, T.; Abe, T.; Nomoto, M.; Furuno, T.; Takeuchi, I.; Hishimoto, A. Relationship of Emergency Department Visits for Suicide Attempts with Meteorological and Air Pollution Conditions. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 333, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, L.; Cox, B.; Nemery, B.; Deboosere, P.; Nawrot, T.S. High Temperatures Trigger Suicide Mortality in Brussels, Belgium: A Case-Crossover Study (2002–2011). Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaggio, K.; Leduc, S.D.; Rice, R.B.; Duffney, P.F.; Foley, K.M.; Holder, A.L.; McDow, S.; Weaver, C.P. Beyond Particulate Matter Mass: Heightened Levels of Lead and Other Pollutants Associated with Destructive Fire Events in California. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14272–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso-Álvarez, A.; Simón, L.; Nuñez, O.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Martín-Méndez, I.; Bel-lán, A.; López-Abente, G.; Merlo, J.; Fernandez-Navarro, P.; Galán, I. Association between Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Topsoil and Mental Health in the Adult Population of Spain. Environ. Res. 2019, 179, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, N.; Galarneau, J.M.; Melnyk, A.; Patten, S. Childhood Care and Abuse in Firefighters Assessed for Mental Ill-Health Following the Fort McMurray Fire of May 2016. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, R.P.; Schemmel-Rettenmeier, L.; Frommelt-Kuhle, M. Conducting Research During Disasters. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2012, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, J.M.; Chen, Z.; Williams, K.D.; Jensen-Campbell, L.A. Opportunities and Challenges for Studying Disaster Survivors. Anal. Social Issues Public Policy 2006, 6, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Location and Wildfire (Year of Event) | Population | Outcome Assessment Time | Mental Health Outcomes (Setting and Measures) | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amster et al. (2018) [19] | Israel, Carmel Forest Fire (2010) | n = 204 male (97%) firefighters and police. Mean age = 36.5 years. | ~1 year | In-person interview: fatigue, stress-related symptoms, PTSD symptoms including difficulty sleeping, recurrent dreams, and avoidance. | Approximately one year after the wildfire event, 25% reported at least one acute stress-related symptom after the wildfire event. A total of 10% reported PTSD-related symptoms. |

| Leykin et al. (2013) [14] | Israel, Carmel Forest Fire (2010) | n = 65 males (59 firefighters, 6 police officers). Ages 17–59 years. | 1 month | In-person interview: Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS); Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R); Posttraumatic Growth—Short Form (PTGI_SF). | One month after the wildfire event, 12.3% and 18.5% of firefighters met criteria for PTSD and probable PTSD, respectively. The intrusion subscale mean score was significantly higher than the avoidance and hyperarousal subscales (F(2, 128) = 20.57, p < 0.001). The mean IES-R score was 15.60 (0–54) and was significantly different than zero (t(64) = 8.52, p < 0.001). Adjusting for gender; age/ethnicity; religion; marital status; highest education level; income level. |

| Cherry et al. (2021) [9] | Canada, Fort McMurray Fire (2016) | n = 998 (n = 895 male, n = 103 female) screened. n = 192 (n = 176 male, n = 16 female) assessed. Mean age of participants assessed = 38.1 years. | ~4.5 years | Online questionnaires: PCL-5 screening for PTSD and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); subsample with clinically high scores were assessed through in-person structured clinical interview (SCID-5) and diagnosed via Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). | A total of 4.5 years after wildfire exposure, the most frequent diagnoses were PTSD (n = 78), anxiety disorder (n = 59), and depressive disorder (n = 55). The estimated prevalence within the cohort was 21.4% diagnosed with PTSD, 15.8% with an anxiety disorder, and 14.3% with a depressive disorder. |

| Theleritis et al. (2020) [18] | Greece, Greek Fires of Ilia (2007) | n = 102 male firefighters. Mean age = 40.0 years. | 1 month | In-person interview: PTSD diagnosis (ICD-10 research diagnostic criteria); fear of dying during exposure (self-reported Likert-style questionnaire); Coping Styles (AECOM-CSQ self-administered questionnaire); Anxiety Inventory; psychiatric diagnoses confirmed using Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. | One month after the wildfire event, 18.6% of the sample was diagnosed with PTSD. Adjusting for covariates, the coping styles, minimization (OR 1.14; 95%CI 1.01, 1.28), and blame (OR 1.11; 95%CI 1.00, 1.24) were significantly associated with PTSD of those diagnosed. Adjusted for age, education level, family status, employment status, presence of a disease, experience from other disasters, and fear of death/dying. |

| Psarros et al. (2018) [17] | Greece, Greek Fires of Ilia (2007) | n = 102 male firefighters. Mean age = 40.0 years. | 1 month | In-person interview: PTSD diagnosis (ICD-10 research diagnostic criteria); fear of dying during exposure (self-reported Likert-style questionnaire); State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; psychopathology and depression (SCL-90); those scoring high on the SCL-90 were additionally screened with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; extraversion and neuroticism (modified short Greek Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI)); Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS); psychiatric diagnoses confirmed using Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. | One month after the wildfires, 18.6% were diagnosed with PTSD and 23.5% were diagnosed with insomnia. Of the 10 participants who scored high on the SCL-90, only 1 met criteria for major depressive disorder via the HDRS-17. Those with a greater self-reported fear of dying compared to no fear (OR 2.89 95%CI 1.04, 8.10), those with increased scores on the SCL-90 for neuroticism (OR 1.34 95%CI 1.02, 1.75) and depression (OR 1.20 95%CI 1.08, 1.34), and those with insomnia (OR 3.24 95%CI 1.10, 9.53) were more likely to have PTSD. |

| Doley et al. (2016) [16] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 277 (n = 271 male, n = 6 female). Mean age = 42.2 years. | 7 years | Mailed self-completed questionnaires: PTSD symptoms via the 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12); Impact of Events Scale (IES); Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WOQ); Life Events Inventory: The List of Threatening Experiences. | Seven years after the bushfire event, 28% of respondents met criteria for psychiatric impairment on the GHQ-12. When considering predictors of psychiatric impairment, adverse life events (B 0.408, p < 0.001) and intrusion measured via the IES (B 0.276, p < 0.001) were significant. |

| McFarlane. (1986) [25] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 469 firefighters. Mean age = 35.1 years. | 4, 11, 29 months | In-person interview: PTSD symptoms assessed via the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) at 4, 11, and 29 months after the event. Clinical interview conducted with subsample (n = 49) 8 months after the event. | The prevalence of PTSD diagnosis was 32%, 27%, and 30% at 4, 11, and 29 months, respectively. Between 4 and 11 months, there was a significant drop in identified cases (z = 1.80, p < 0.05) but not between 4 and 29 months (z = 0.62, p > 0.05). A total of 53% of those with PTSD at 4 months postevent were also diagnosed 29 months postevent. A total of 35% of respondents were found to have PTSD at all three occasions. |

| McFarlane et al. (1987) [23] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 469 firefighters. Mean age = 35.1 years. | 4 and 11 months | In-person interview: At 4 months postevent, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Inventory of Events (IES). At 11 months, GHQ-12. | GHQ-12 scores at 11 months postevent were significantly correlated with fire exposure (p = 0.007), perceived threat (p = 0.004), property loss (p = 0.000), recent life events (p = 0.000), and previous fires experienced (p = 0.006). A total of 30% of the sample was found to have PTSD disorder. Compared to those without a diagnosis, those with PTSD had significantly greater fire exposure (t = −2.3, p = 0.02), hours fighting fires (t = −3.0, p = 0.003), perceived threat (t = −2.5, p = 0.01), property loss (t = −4.7, p = 0.000), and recent life events (t = −3.16, p = 0.000). Adjusting for marital status; age; origin of birth; individual experience of disaster; extent of personal losses, both material and personal; personal history of psychiatric illness/treatment. |

| McFarlane et al. (1988) [21] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 469 firefighters. n = 315 final participants included. Mean age = 35.1 years. | 4, 11, 29 months | In-person interview: At 4 months postevent, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Inventory of Events (IES). At 11 months postevent, brief life events inventory, IES, and GHQ-12. At 29 months, brief life events, IES, GHQ-12, and Eysneck Personality Inventory (EPI). | Three types of PTSD were defined including delayed onset, acute, and chronic. Of the participants that responded at all three timepoints, 50.2% had no disorder, 9.2% had acute PTSD, 21% chronic, and 19.7% delayed onset (3.2% persistent, 5.4% 11 months only, and 11.1% 29 months only). |

| McFarlane (1988) [26] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 355 firefighters. Mean age = 35.1 years. Matched controls for marital status, ethnic background, experience during the fire, and GHQ-12 scores at 11 months postevent. | 11 months | In-person interview: At 11 months postevent, brief life events inventory, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), and Inventory of Events (IES). N = 49 completed a structured clinical interview to validate PTSD detection via the GHQ-12. | At 11 months postevent, distress (IES scores) accounted for only 14% of variance of the GHQ-12 (B = 0.32, p < 0.000). |

| McFarlane (1988) [24] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 45 firefighters randomly selected from cohort with n = 11 meeting criteria for PTSD. | 4 and 8 months | In-person interview: General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Inventory of Events (IES). Structured clinical interview. | Those with and without PTSD were not significantly different in their experience of the wildfire and losses, injury, exposure, or perceived threat. In a two-tailed t-test, IES avoidance subscales at 4 months (t = 2.66, p ≤ 0.01) and GHQ scores at 4 (t = 3.06, p ≤ 0.01) and 8 months (t = 2.50, p ≤ 0.05) were significantly higher in the PTSD group. Having a family history of psychiatric disorders showed a nonsignificant trend difference between the PTSD and non-PTSD group (x2 = 2.82, p = 0.09). |

| McFarlane. (1989) [22] | Australia, Ash Wednesday Fires (1983) | n = 395 (11 months) and 337 (29 months) firefighters. Mean age = 36.1 years. | 4, 11, 29 months | In-person interview: At 4 months postevent, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and Inventory of Events (IES). At 11 months postevent, brief life events inventory, IES, and GHQ-12. At 29 months, brief life events, IES, GHQ-12, and Eysneck Personality Inventory (EPI). | The prevalence of PTSD diagnosis was 32%, 27%, and 30% at 4, 11, and 29 months, respectively, as previously reported. At 4 months, the GHQ-12 score was not significantly predicted by the posttraumatic distress as measured by the IES. Symptoms at 4 months significantly predicted GHQ-12 scores at 11 and 29 months. Adjusting for age and social class. |

| Smith et al. (2020) [15] | Australia, Black Summer Bushfires (2019–2020) | n = 58 male and female firefighters. Mean age = 46. | ~1 year | Telephone or video individual interviews using semistructured script regarding self-experience; mental health and well-being impact of wildfires; help-seeking behaviors; organization support of mental health and well-being. | Within a year of the event, 28 respondents reported experiences of PTSD symptoms, 8 with a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. Thirty-two respondents reported not seeking mental health support in the following year since the event. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonita, I.; Halabicky, O.M.; Liu, J. Exposure to Wildfires Exposures and Mental Health Problems among Firefighters: A Systematic Review. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15010078

Bonita I, Halabicky OM, Liu J. Exposure to Wildfires Exposures and Mental Health Problems among Firefighters: A Systematic Review. Atmosphere. 2024; 15(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonita, Isabelle, Olivia M. Halabicky, and Jianghong Liu. 2024. "Exposure to Wildfires Exposures and Mental Health Problems among Firefighters: A Systematic Review" Atmosphere 15, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15010078

APA StyleBonita, I., Halabicky, O. M., & Liu, J. (2024). Exposure to Wildfires Exposures and Mental Health Problems among Firefighters: A Systematic Review. Atmosphere, 15(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15010078