Transcriptome- and Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Tic Spectrum Disorder in Discordant Monozygotic Twins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Monozygotic Twin TSD Cohort

2.2. RNA Sequencing

2.3. DNA Methylation

2.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Differentially Methylated Probes

2.5. Expression Quantitative Trait Methylation (eQTM)

2.6. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

3. Results

3.1. Data Exploration and Statistical Model Generation

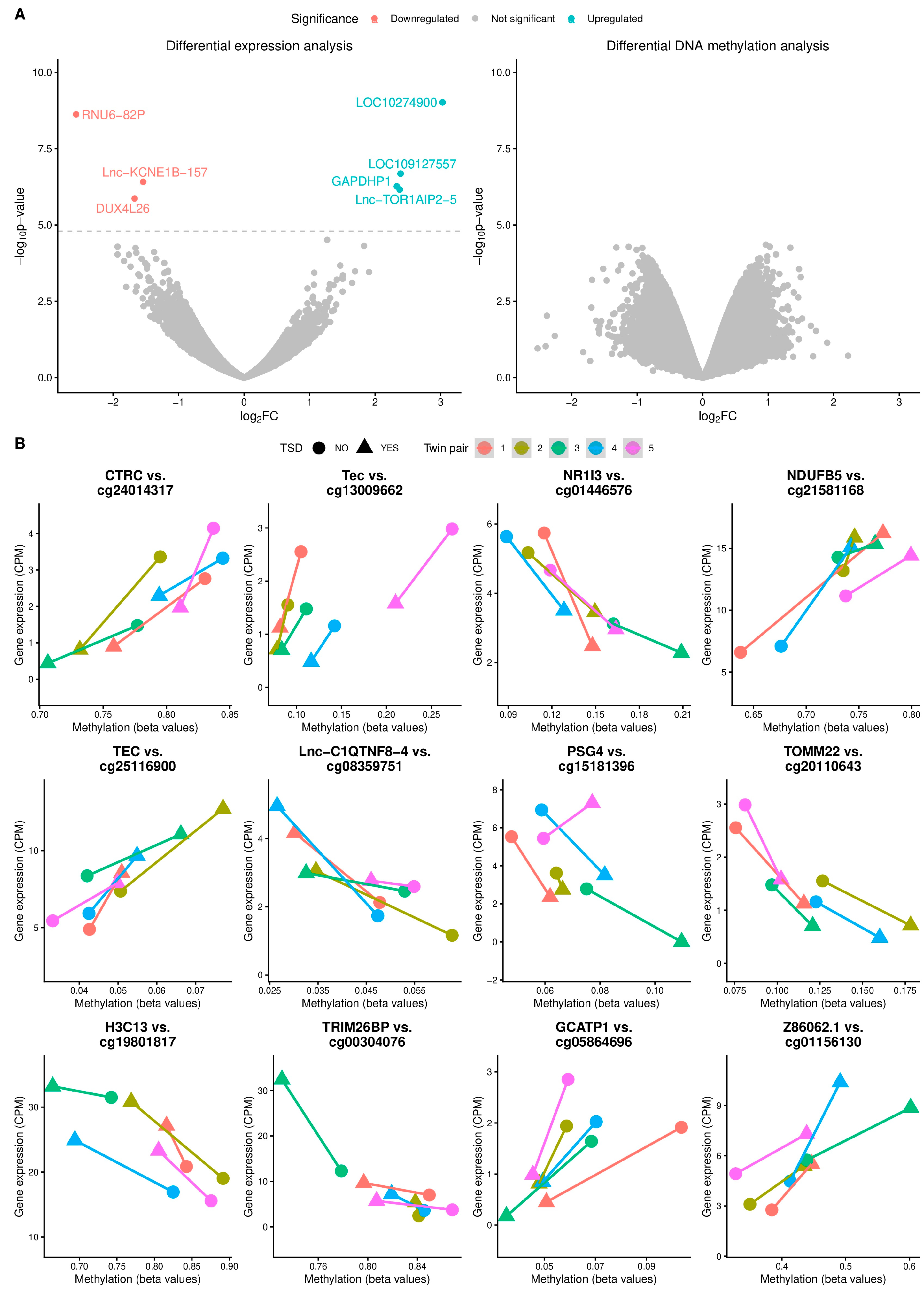

3.2. Differential Expression and Methylation Analyses

3.3. Expression Quantitative Trait Methylation (eQTM) Analysis

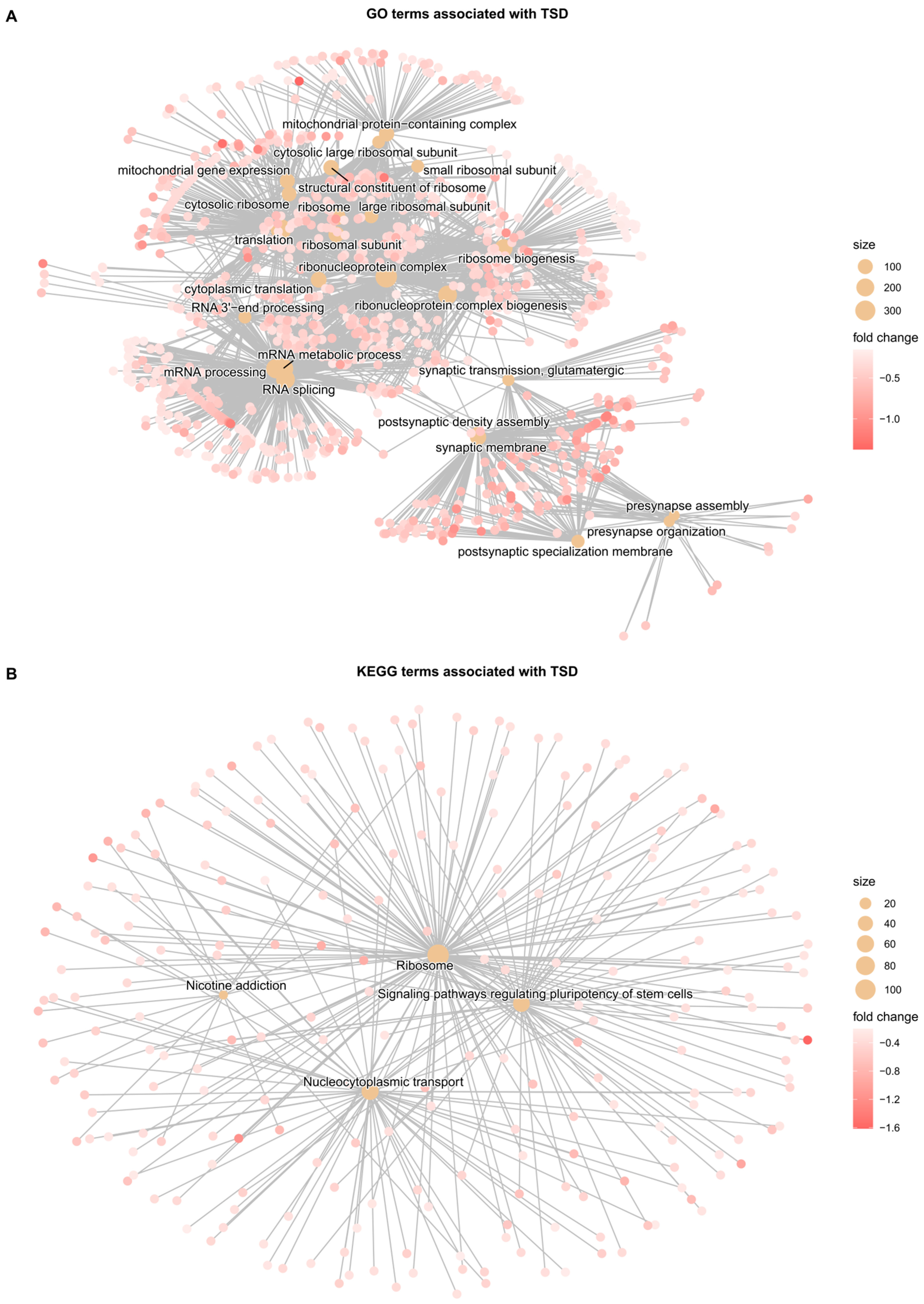

3.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ADHD | Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| CPM | Counts per million |

| CTD | Chronic tic disorder |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| DMP | Differentially methylated probe |

| DNAm | DNA methylation |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| eQTM | Expression quantitative trait methylation |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| GTS | Gilles de la Tourette syndrome |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gens and Genomes |

| LCPM | Log-transformed counts per million |

| OCD | Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| Q-Q | Quantile–quantile |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| TS | Tourette syndrome |

| TSD | Tic spectrum disorder |

| YGTSS | Yale Global Tic Severity Scale |

References

- Johnson, K.A.; Worbe, Y.; Foote, K.D.; Butson, C.R.; Gunduz, A.; Okun, M.S. Tourette Syndrome: Clinical Features, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, D.; Dale, R.C.; Gilbert, D.L.; Giovannoni, G.; Leckman, J.F. Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Tourette Syndrome: A Critical Review. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-J.; Wong, L.-C.; Lee, W.-T. Immunological Dysfunction in Tourette Syndrome and Related Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Vahl, K.R.; Sambrani, T.; Jakubovski, E. Tic Disorders Revisited: Introduction of the Term “Tic Spectrum Disorders”. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, C.; Mol Debes, N.; Rask, C.U.; Lange, T.; Skov, L. Course of Tourette Syndrome and Comorbidities in a Large Prospective Clinical Study. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Delgar, B.; Servera, M.; Coffey, B.J.; Lázaro, L.; Openneer, T.; Benaroya-Milshtein, N.; Steinberg, T.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Dietrich, A.; Morer, A.; et al. Tic Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Does the Clinical Presentation Differ in Males and Females? A Report by the EMTICS Group. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauls, D.L.; Towbin, K.E.; Leckman, J.F.; Zahner, G.E.P.; Cohen, D.J. Gilles de La Tourette’s Syndrome and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Evidence Supporting a Genetic Relationship. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1986, 43, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lin, W.; Tsai, F.J.; Chou, I.C. Current Understanding of the Genetics of Tourette Syndrome. Biomed. J. 2022, 45, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldridge, R.; Sweet, R.; Lake, C.R.; Ziegler, M.; Shapiro, A.K. Gilles de La Tourette’s Syndrome: Clinical, Genetic, Psychologic, and Biochemical Aspects in 21 Selected Families. Neurology 1977, 27, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix-Cols, D.; Isomura, K.; Pérez-Vigil, A.; Chang, Z.; Rück, C.; Johan Larsson, K.; Leckman, J.F.; Serlachius, E.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P. Familial Risks of Tourette Syndrome and Chronic Tic Disorders. A Population-Based Cohort Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Sul, J.H.; Tsetsos, F.; Nawaz, M.S.; Huang, A.Y.; Zelaya, I.; Illmann, C.; Osiecki, L.; Darrow, S.M.; Hirschtritt, M.E.; et al. Interrogating the Genetic Determinants of Tourette’s Syndrome and Other Tic Disorders Through Genome-Wide Association Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelson, J.F.; Kwan, K.Y.; O’Roak, B.J.; Baek, D.Y.; Stillman, A.A.; Morgan, T.M.; Mathews, C.A.; Pauls, D.L.; Rašin, M.R.; Gunel, M.; et al. Sequence Variants in SLITRK1 Are Associated with Tourette’s Syndrome. Science 2005, 310, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan-Sencicek, A.G.; Stillman, A.A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Bilguvar, K.; O’Roak, B.J.; Mason, C.E.; Abbott, T.; Gupta, A.; King, R.A.; Pauls, D.L.; et al. L-Histidine Decarboxylase and Tourette’s Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrini, G.; Pasquini, M.; Aurilia, C.; Berardelli, I.; Breedveld, G.; Oostra, B.A.; Bonifati, V.; Berardelli, A. A Large Italian Family with Gilles de La Tourette Syndrome: Clinical Study and Analysis of the SLITRK1 Gene. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, R.A.; Lee, S.; Eapen, V. Pathogenetic Model for Tourette Syndrome Delineates Overlap with Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders Including Autism. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijun, L.; Zaiwang, L.; Anyuan, L.; Shuzhen, W.; Fanghua, Q.; Lin, Z.; Hong, L. Abnormal Expression of Dopamine and Serotonin Transporters Associated with the Pathophysiologic Mechanism of Tourette Syndrome. Neurol. India 2010, 58, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; Pingault, J.B.; Cecil, C.A.M.; Gaunt, T.R.; Relton, C.L.; Mill, J.; Barker, E.D. Epigenetic Profiling of ADHD Symptoms Trajectories: A Prospective, Methylome-Wide Study. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiele, M.A.; Lipovsek, J.; Schlosser, P.; Soutschek, M.; Schratt, G.; Zaudig, M.; Berberich, G.; Köttgen, A.; Domschke, K. Epigenome-Wide DNA Methylation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.S.; Camprubí, C.; Tümer, Z.; Martínez, F.; Milà, M.; Monk, D. Screening Individuals with Intellectual Disability, Autism and Tourette’s Syndrome for KCNK9 Mutations and Aberrant DNA Methylation within the 8q24 Imprinted Cluster. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2014, 165B, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.K.; Chi, S.; Nam, G.H.; Baek, K.W.; Ahn, K.; Ahn, Y.; Kang, J.; Lee, M.S.; Gim, J.A. Epigenome-Wide Association Study for Tic Disorders in Children: A Preliminary Study in Korean Population. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2024, 22, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilhão, N.R.; Padmanabhuni, S.S.; Pagliaroli, L.; Barta, C.; Smit, D.J.A.; Cath, D.; Nivard, M.G.; Baselmans, B.M.L.; Van Dongen, J.; Paschou, P.; et al. Epigenome-Wide Association Study of Tic Disorders. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2015, 18, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, J.E.; Scahill, L.; Lombroso, P.J.; King, R.A.; Leckman, J.F. Tourette Syndrome and Tic Disorders: A Decade of Progress. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildonen, M.; Levy, A.M.; Hansen, C.S.; Bybjerg-Grauholm, J.; Skytthe, A.; Debes, N.M.; Tan, Q.; Tümer, Z. EWAS of Monozygotic Twins Implicate a Role of MTOR Pathway in Pathogenesis of Tic Spectrum Disorder. Genes 2021, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. EdgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, M.J.; Jaffe, A.E.; Corrada-Bravo, H.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Feinberg, A.P.; Hansen, K.D.; Irizarry, R.A. Minfi: A Flexible and Comprehensive Bioconductor Package for the Analysis of Infinium DNA Methylation Microarrays. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Johnson, W.E.; Parker, H.S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Storey, J.D. The Sva Package for Removing Batch Effects and Other Unwanted Variation in High-Throughput Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 882–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabalin, A.A. Matrix EQTL: Ultra Fast EQTL Analysis via Large Matrix Operations. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. ClusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkevich, G.; Sukhov, V.; Budin, N.; Shpak, B.; Artyomov, M.N.; Sergushichev, A. Fast Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Biorxiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, E.; Picardi, E.; Tullo, A.; Pesole, G.; D’Erchia, A.M. Identification of Deregulated LncRNAs in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Integrated Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis of Hippocampus and Fusiform Gyrus RNA-Seq Datasets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1437278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, C.; Slavin, M.; Ansseau, E.; Lancelot, C.; Bah, K.; Lassche, S.; Fiévet, M.; Greco, A.; Tomaiuolo, S.; Tassin, A.; et al. The Double Homeodomain Protein DUX4c Is Associated with Regenerating Muscle Fibers and RNA-Binding Proteins. Skelet. Muscle 2023, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, D.; Agnelli, L.; Taiana, E.; Galletti, S.; Manzoni, M.; Todoerti, K.; Musto, P.; Strozzi, F.; Neri, A. Distinct LncRNA Transcriptional Fingerprints Characterize Progressive Stages of Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 14814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccitto, M.; Wolin, S.L. Ro60 and Y RNAs: Structure, Functions and Roles in Autoimmunity. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 54, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, K.; Pang, L.; Fei, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J. ANKRD22 Is a Potential Novel Target for Reversing the Immunosuppressive Effects of PMN-MDSCs in Ovarian Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCGR1A—High Affinity Immunoglobulin Gamma Fc Receptor I—Homo Sapiens (Human)|UniProtKB|UniProt. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P12314/entry#function (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Le, D.T.; Florez, M.A.; Kus, P.; Tran, B.T.; Kain, B.; Zhu, Y.; Christensen, K.; Jain, A.; Malovannaya, A.; King, K.Y. BATF2 Promotes HSC Myeloid Differentiation by Amplifying IFN Response Mediators during Chronic Infection. iScience 2023, 26, 106059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Guler, R.; Parihar, S.P.; Schmeier, S.; Kaczkowski, B.; Nishimura, H.; Shin, J.W.; Negishi, Y.; Ozturk, M.; Hurdayal, R.; et al. Batf2/Irf1 Induces Inflammatory Responses in Classically Activated Macrophages, Lipopolysaccharides, and Mycobacterial Infection. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 6035–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Geest, R.; Penaloza, H.F.; Xiong, Z.; Gonzalez-Ferrer, S.; An, X.; Li, H.; Fan, H.; Tabary, M.; Nouraie, S.M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. BATF2 Enhances Proinflammatory Cytokine Responses in Macrophages and Improves Early Host Defense against Pulmonary Klebsiella Pneumoniae Infection. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2022, 325, L604–L616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkey, R.A.; Smith, B.C.; Habean, M.L.; Williams, J.L. BATF2 Is a Regulator of Interferon-γ Signaling in Astrocytes during Neuroinflammation. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, M.; Liu, K.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Wei, Y.; Long, Y.; He, W.; Shi, X.; et al. BATF2 Balances the T Cell-Mediated Immune Response of CADM with an Anti-MDA5 Autoantibody. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 551, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Chang, Y.; Huang, K.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. The Role of BATF2 Deficiency in Immune Microenvironment Rearrangement in Cervical Cancer—New Biomarker Benefiting from Combination of Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 126, 111199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dai, L.; Shi, G.; Deng, J.; Luo, Q.; Xie, Q.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Lin, Y.; et al. BATF2 Prevents Glioblastoma Multiforme Progression by Inhibiting Recruitment of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Oncogene 2021, 40, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, N.; Luo, J.; Duan, M.; Shi, N. The Pseudogene GBP1P1 Suppresses Influenza A Virus Replication by Acting as a Protein Decoy for DHX9. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0073824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemaru, H.; Yamane, F.; Fukushima, K.; Matsuki, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Ebina, I.; Kuniyoshi, K.; Tanaka, H.; Maruyama, K.; Maeda, K.; et al. Antitumor Effect of Batf2 through IL-12 P40 up-Regulation in Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7331–E7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Fan, H.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Shi, T.; Zhang, D.; Lu, G. Ribosomal RNA-Depleted RNA Sequencing Reveals the Pathogenesis of Refractory Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Pneumonia in Children. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Zhou, X.; Feng, W.; Jia, M.; Zhang, X.; An, T.; Luan, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Risk Stratification by Long Non-coding RNAs Profiling in COVID-19 Patients. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.Y.; Guo, Q.; Tong, S.; Wu, C.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Ding, Y.; Wan, J.H.; Chen, S.S.; Wang, S.H. TRAT1 Overexpression Delays Cancer Progression and Is Associated with Immune Infiltration in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 960866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, S.-H.; Ji, Y.-M.; Tong, S.; Li, D.; Ding, X.-C.; Wu, C.-Y. The Roles and Mechanisms of TRAT1 in the Progression of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Med. Sci. 2022, 42, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delesque-Touchard, N.; Pendaries, C.; Volle-Challier, C.; Millet, L.; Salel, V.; Hervé, C.; Pflieger, A.M.; Berthou-Soulie, L.; Prades, C.; Sorg, T.; et al. Regulator of G-Protein Signaling 18 Controls Both Platelet Generation and Function. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Thys, C.; Berry, I.R.; Jarvis, J.; Ortibus, E.; Mumford, A.D.; Freson, K.; Turro, E. Mutations in the U4 SnRNA Gene RNU4-2 Cause One of the Most Prevalent Monogenic Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2165–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonghe, J.; Kim, H.C.; Adedeji, A.; Leitão, E.; Dawes, R.; Chen, Y.; Blakes, A.J.; Simons, C.; Rius, R.; Alvi, J.R.; et al. Saturation Genome Editing of RNU4-2 Reveals Distinct Dominant and Recessive Neurodevelopmental Disorders. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsurka, G.; Appel, M.L.T.; Nastaly, M.; Hallmann, K.; Hansen, N.; Nass, D.; Baumgartner, T.; Surges, R.; Hartmann, G.; Bartok, E.; et al. Loss of the Immunomodulatory Transcription Factor BATF2 in Humans Is Associated with a Neurological Phenotype. Cells 2023, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmookler Reis, R.J.; Atluri, R.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Johnson, J.; Ganne, A.; Ayyadevara, S. “Protein Aggregates” Contain RNA and DNA, Entrapped by Misfolded Proteins but Largely Rescued by Slowing Translational Elongation. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, E.I.; Bien-Willner, G.A.; Li, J.; Hughes, A.E.O.; Giacalone, J.; Chasnoff, S.; Kulkarni, S.; Parmacek, M.; Cole, F.S.; Druley, T.E. Genetic Variation in MKL2 and Decreased Downstream PCTAIRE1 Expression in Extreme, Fatal Primary Human Microcephaly. Clin. Genet. 2013, 85, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, S.; Pan, T.; Yu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. ANKRD22 Is Involved in the Progression of Prostate Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 4106–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Fu, W.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Z.; Liao, H.; Chen, W.; Pan, L.; Zhao, J. ANKRD22 Promotes Progression of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer through Transcriptional up-Regulation of E2F1. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, S.; Zhu, Y. ANKRD22 Is a Novel Therapeutic Target for Gastric Mucosal Injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Ravan, M.; Karimi-Sani, I.; Aria, H.; Hasan-Abad, A.M.; Banasaz, B.; Atapour, A.; Sarab, G.A. Screening and Identification of Potential Biomarkers for Pancreatic Cancer: An Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 249, 154726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Zhong, D.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Zhu, Y. ANKRD22 Drives Rapid Proliferation of Lgr5+ Cells and Acts as a Promising Therapeutic Target in Gastric Mucosal Injury. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 1433–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhane, T.; Holm, A.; Karstensen, K.T.; Petri, A.; Ilieva, M.S.; Krarup, H.; Vyberg, M.; Løvendorf, M.B.; Kauppinen, S. Knockdown of the Long Noncoding RNA PURPL Induces Apoptosis and Sensitizes Liver Cancer Cells to Doxorubicin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savinovskaya, Y.I.; Nushtaeva, A.A.; Savelyeva, A.V.; Morozov, V.V.; Ryabchikova, E.I.; Kuligina, E.V.; Richter, V.A.; Semenov, D.V. Human Blood Extracellular Vesicles Activate Transcription of NF-KB-Dependent Genes in A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 6028–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskiewicz, K.; Maleszka-Kurpiel, M.; Matuszewska, E.; Kabza, M.; Rydzanicz, M.; Malinowski, R.; Ploski, R.; Matysiak, J.; Gajecka, M. The Impaired Wound Healing Process Is a Major Factor in Remodeling of the Corneal Epithelium in Adult and Adolescent Patients With Keratoconus. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebifar, H.; Sabbaghian, A.; Farazmandfar, T.; Golalipour, M. Construction and Analysis of Pseudogene-Related CeRNA Network in Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Pan, M.; Sheng, Y.; Jia, E.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Tu, J.; Bai, Y.; Cai, L.; Ge, Q. Extracellular Cell-Free RNA Profile in Human Large Follicles and Small Follicles. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 940336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Meng, S.; Tsuji, Y.; Arao, Y.; Saito, Y.; Sato, H.; Motooka, D.; Uchida, S.; Ishii, H. RN7SL1 May Be Translated under Oncogenic Conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2312322121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Matas, J.; Duran-Sanchon, S.; Lozano, J.J.; Ferrero, G.; Tarallo, S.; Pardini, B.; Naccarati, A.; Castells, A.; Gironella, M. SnoRNA Profiling in Colorectal Cancer and Assessment of Non-Invasive Biomarker Capacity by DdPCR in Fecal Samples. iScience 2024, 27, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.I.; Veerapandian, R.; Das, K.; Chacon, J.A.; Gadad, S.S.; Dhandayuthapani, S. Pathogenic Mycoplasmas of Humans Regulate the Long Noncoding RNAs in Epithelial Cells. Noncoding RNA Res. 2023, 8, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Nie, Y.; Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, K.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Identification of Immune-Related Prognostic Genes and LncRNAs Biomarkers Associated With Osteosarcoma Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itami-Matsumoto, S.; Hayakawa, M.; Uchida-Kobayashi, S.; Enomoto, M.; Tamori, A.; Mizuno, K.; Toyoda, H.; Tamura, T.; Akutsu, T.; Ochiya, T.; et al. Circulating Exosomal MiRNA Profiles Predict the Occurrence and Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Direct-Acting Antiviral-Induced Sustained Viral Response. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilha, J.C.F.; Cursino, M.A.; Borges, J.B.; Torso, N.G.; Bastos, L.B.; Oliveira, J.M.; Cobaxo, T.S.; Pincinato, E.C.; Hirata, M.H.; Geraldo, M.V.; et al. MiR-3168, MiR-6125, and MiR-4718 as Potential Predictors of Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, J.; Tan, K.; Liu, J.; Cao, S.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Diao, R.; Wang, L. The Alteration of M6A Modification at the Transcriptome-Wide Level in Human Villi During Spontaneous Abortion in the First Trimester. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 861853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shih, C.M.; Tsai, L.W.; Dubey, R.; Gupta, D.; Chakraborty, T.; Sharma, N.; Singh, A.V.; Swarup, V.; Singh, H.N. Transcriptomic Profiling Unravels Novel Deregulated Gene Signatures Associated with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Bioinformatics Approach. Genes 2022, 13, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsugair, Z.; Perrot, J.; Descotes, F.; Lopez, J.; Champagnac, A.; Pissaloux, D.; Castain, C.; Onea, M.; Céruse, P.; Philouze, P.; et al. Characterization of a Molecularly Distinct Subset of Oncocytic Pleomorphic Adenomas/Myoepitheliomas Harboring Recurrent ZBTB47-AS1::PLAG1 Gene Fusion. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2024, 48, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Qiu, S.Q.; Wang, Q.; Zuo, J.L. Regulator of G Protein Signalling 18 Promotes Osteocyte Proliferation by Activating the Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase Signalling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 53, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Li, H.; Peng, Z.; Ke, D.; Fu, H.; Zheng, X. Identification of Plasma RGS18 and PPBP MRNAs as Potential Biomarkers for Gastric Cancer Using Transcriptome Arrays. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R.C.; Merheb, V.; Pillai, S.; Wang, D.; Cantrill, L.; Murphy, T.K.; Ben-Pazi, H.; Varadkar, S.; Aumann, T.D.; Horne, M.K.; et al. Antibodies to Surface Dopamine-2 Receptor in Autoimmune Movement and Psychiatric Disorders. Brain 2012, 135, 3453–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addabbo, F.; Baglioni, V.; Schrag, A.; Schwarz, M.J.; Dietrich, A.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Martino, D.; Buttiglione, M.; Anastasiou, Z.; Apter, A.; et al. Anti-Dopamine D2 Receptor Antibodies in Chronic Tic Disorders. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2020, 62, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Mataix-Cols, D. General Health and Mortality in Tourette Syndrome and Chronic Tic Disorder: A Mini-Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 119, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.K.; Storch, E.A.; Turner, A.; Reid, J.M.; Tan, J.; Lewin, A.B. Maternal History of Autoimmune Disease in Children Presenting with Tics and/or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 229, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Shi, H.; Smith, J.D.; Chen, X.; Noe, D.A.; Cedervall, T.; Yangt, D.D.; Eynon, E.; Brash, D.E.; Kashgarian, M.; et al. A Lupus-like Syndrome Develops in Mice Lacking the Ro 60-KDa Protein, a Major Lupus Autoantigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7503–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dawes, R.; Kim, H.C.; Ljungdahl, A.; Stenton, S.L.; Walker, S.; Lord, J.; Lemire, G.; Martin-Geary, A.C.; Ganesh, V.S.; et al. De Novo Variants in the RNU4-2 SnRNA Cause a Frequent Neurodevelopmental Syndrome. Nature 2024, 632, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson Linnér, R.; Mallard, T.T.; Barr, P.B.; Sanchez-Roige, S.; Madole, J.W.; Driver, M.N.; Poore, H.E.; de Vlaming, R.; Grotzinger, A.D.; Tielbeek, J.J.; et al. Multivariate Analysis of 1.5 Million People Identifies Genetic Associations with Traits Related to Self-Regulation and Addiction. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoda, Z.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Chymotrypsin C (Caldecrin) Stimulates Autoactivation of Human Cationic Trypsinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 11879–11886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmola, R.; Bence, M.; Carpentieri, A.; Szabó, A.; Costello, C.E.; Samuelson, J.; Sahin-Tóth, M. Chymotrypsin C Is a Co-Activator of Human Pancreatic Procarboxypeptidases A1 and A2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 286, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, G.L.; Hyman, S.L.; Mooney, R.A.; Kirby, R.S. Plasma Amino Acids Profiles in Children with Autism: Potential Risk of Nutritional Deficiencies. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.A.; Arnold, L.E.; Bostrom, S.; Aman, M.G. 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research: Chymotrypsin: Evidence of a Novel Pancreatic Insufficiency in Children with ASD? Available online: https://insar.confex.com/imfar/2017/webprogram/Paper23908.html (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Heil, M.; Pearson, D.A.; Fallon, J. 2014 International Meeting for Autism Research: Low Endogenous Fecal Chymotrypsin: A Possible Biomarker for Autism? Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268131323_Low_Endogenous_Fecal_Chymotrypsin_A_Possible_Biomarker_for_Autism (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Pearson, D.A.; Hendren, R.L.; Heil, M.F.; McIntyre, W.R.; Raines, S.R. Pancreatic Replacement Therapy for Maladaptive Behaviors in Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2344136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.A.; Rudnik-Leven, F. Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Substance Abuse. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 931, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srichawla, B.S.; Telles, C.C.; Schweitzer, M.; Darwish, B. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Substance Use Disorder: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e24068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dalsberg, J.; Jespersgaard, C.; Levy, A.M.; Asplund, A.M.; Bagger, F.O.; Debes, N.M.; Tan, Q.; Tümer, Z.; Hildonen, M. Transcriptome- and Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Tic Spectrum Disorder in Discordant Monozygotic Twins. Genes 2026, 17, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010097

Dalsberg J, Jespersgaard C, Levy AM, Asplund AM, Bagger FO, Debes NM, Tan Q, Tümer Z, Hildonen M. Transcriptome- and Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Tic Spectrum Disorder in Discordant Monozygotic Twins. Genes. 2026; 17(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleDalsberg, Jonas, Cathrine Jespersgaard, Amanda M. Levy, Anna Maria Asplund, Frederik Otzen Bagger, Nanette M. Debes, Qihua Tan, Zeynep Tümer, and Mathis Hildonen. 2026. "Transcriptome- and Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Tic Spectrum Disorder in Discordant Monozygotic Twins" Genes 17, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010097

APA StyleDalsberg, J., Jespersgaard, C., Levy, A. M., Asplund, A. M., Bagger, F. O., Debes, N. M., Tan, Q., Tümer, Z., & Hildonen, M. (2026). Transcriptome- and Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Tic Spectrum Disorder in Discordant Monozygotic Twins. Genes, 17(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010097