Sequencing and Analysis of mtDNA Genomes from the Teeth of Early Medieval Horses in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

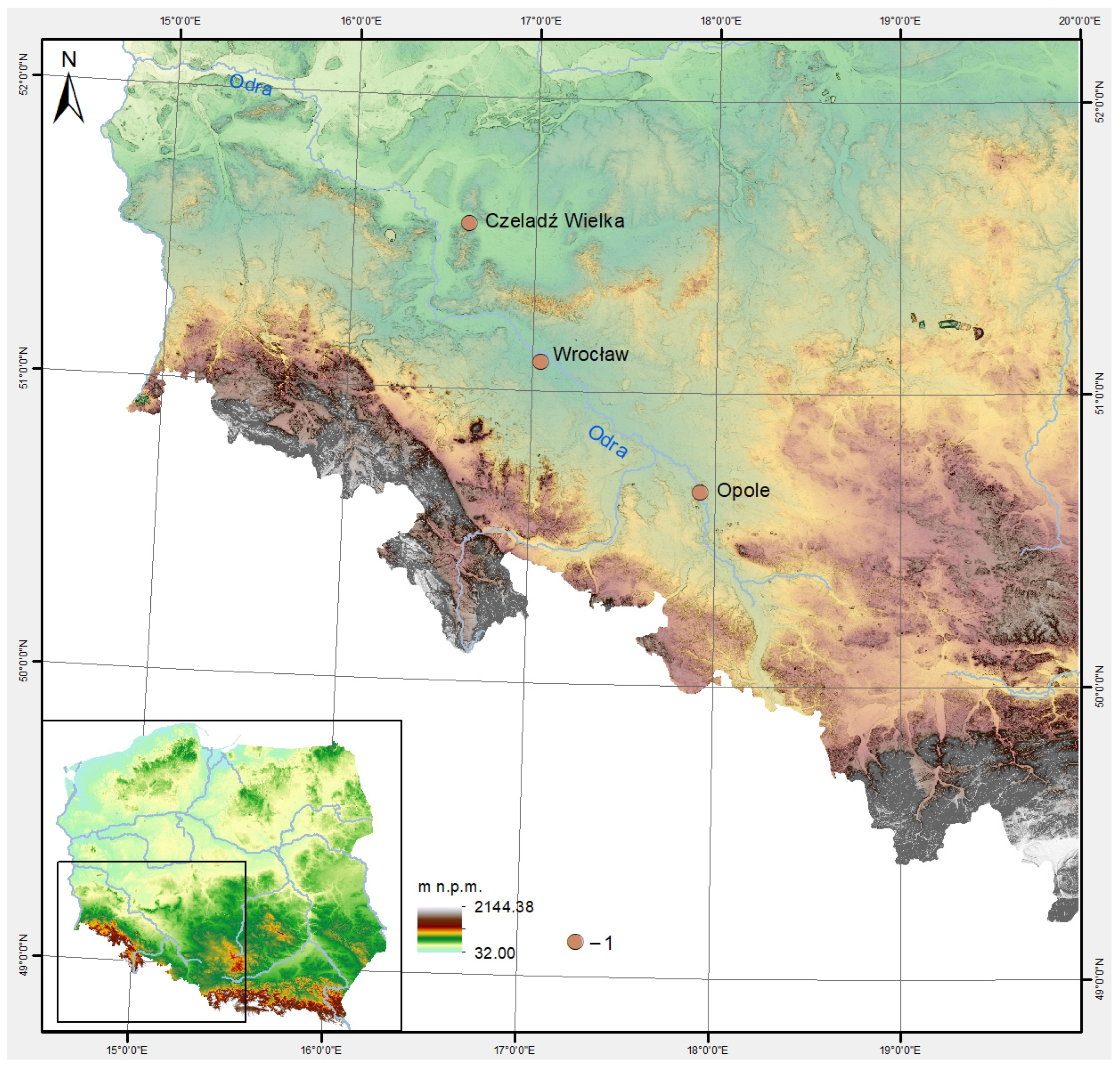

2.1. Characteristics of the Sample Collection

2.2. mtDNA Genomes Sequencing and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reitz, E.; Wing, E. Zooarchaeology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Gonzalez, D. An Introduction to Zooarchaeology; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Gal, E. Pathological lesions in working animals. In Shuffling Nags, Lame Ducks. The Archaeology of Animals Disease; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 130–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, L.; Gal, E. Care or Neglect? Evidence of Animal Disease in Archaeology. In Proceedings of the 6th Meeting of the Animal Palaeopathology Working Group of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ), Budapest, Hungary, 26–29 May 2016; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Makowiecki, D.; Chudziak, W.; Szczepanik, P.; Janeczek, M.; Pasicka, E. Horses in the Early Medieval (10th–13th c.) Religious Rituals of Slavs in Polish Areas—An Archaeozoological, Archaeological and Historical Overview. Animals 2022, 12, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowiecki, D.; Janeczek, M.; Pasicka, E.; Rozwadowska, A.; Ciaputa, R.; Kocińska, K. Pathologies on a horse skeleton from the early medieval stronghold in Gdańsk (Poland). Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2022, 32, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczek, M.; Makowiecki, D.; Rozwadowska, A.; Chudziak, W.; Pasicka, E. Pathological Changes in Early Medieval Horses from Different Archaeological Sites in Poland. Animals 2024, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, J.; Kowalik, N.; Anczkiewicz, R.; Krajcarz, M.; Makowiecki, D.; Krajcarz, M.T. The application of a genetic algorithm in the correlation of intra-individual isotopic Sr dental records for archaeological and palaeontological reconstruction of years-long mobility. Archaeometry 2025, 67, 1619–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, A.; Olivieri, A.; Soares, P.; Lancioni, H.; Kashani, B.H.; Perego, U.A.; Nergadze, S.G.; Carossa, V.; Santagostino, M.; Capomaccio, S.; et al. Mitochondrial genomes from modern horses reveal the major haplogroups that underwent domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Mashkour, M.; Gaunitz, C.; Fages, A.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Sheikhi, S.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Alquraishi, S.A.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.; Chuang, R.; et al. Zonkey: A simple, accurate and sensitive pipeline to genetically identify equine F1-hybrids in archaeological assemblages. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 78, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbani, A.; Aminou, O.; Machmoum, M.; Germot, A.; Badaoui, B.; Petit, D.; Piro, M. A Systematic Literature Review of Mitochondrial DNA Analysis for Horse Genetic Diversity. Animals 2025, 15, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, L. Ancient Genomes Reveal Unexpected Horse Domestication and Management Dynamics. BioEssays 2020, 42, e1900164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutton-Brock, J. Horse Power. In A History of the Horse and Donkey in Human Societies; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M.A. The origins of horse husbandry on the Eurasian steppe. In Late Prehistoric Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppe; Levine, M.A., Rassamakin, Y.Y., Kislenko, A.M., Tatarintseva, N.S., Eds.; McDonald Institute: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 5–58. [Google Scholar]

- Makowiecki, D.; Chudziak, W.; Wiejacka, M. Preliminary reflections on horse-human relationship in early medieval Poland on the basis of history and archaeozoology. In Archaeologies of Animal Movement, Animals on the Move, Seria: Themes in Contemporary Archaeology; Niinimäki, S., Salmi, A.-K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brzóstkowska, A.; Swoboda, W. Testimonia Najdawniejszych Dziejów Słowian: Pisarze z V–X Wieku; Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wołek, A. Obraz Słowian w dziełach Prokopiusza z Cezarei. Źródła humanistyki europejskiej. Iuvenilia Philol. Crac. 2012, 5, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnatowska, Z. Słowiańszczyzna Południowa; Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Labuda, G. Słowiańszczyzna starożytna i wczesnośredniowieczna. In Antologia Tekstów Źródłowych; Sorus: Poznań, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, T. Relacja Ibrahima Ibn Jakuba z Podróży do Krajów Słowiańskich w Przekazie Al–Bekriego; Wydawnictwa Komisji Historycznej PAU: Warszawa, Poland, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Anonim, G. Kronika polska. In Zakład Narodowy Im; Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radek, T. Morphological investigation into species belonging of tanned animal skins coming from Nakło on Noteć. In Archaeozoology, Proceedings of the IIIrd International Archaeozoological, Agricultural Academy Szczecin, Poland, 23–26 April 1978; Kubasiewicz, M., Ed.; Agricultural Academy: Szczecin, Poland, 1979; Volume 1, pp. 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, K. Wyroby z Kości i Poroża w Kulturze Wczesnośredniowiecznego Ostrowa Tumskiego we Wrocławiu; Uniwersytet Wrocławski Volumen: Wrocław, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, D.; Baca, M.; Wiejacka, M.; Chudziak, W.; Makowiecki, D. Genetic Characterization of Horses in Early Medieval Poland. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowiecki, D.; Wiejacka, M. The Horse (Equus Caballus) in Early Medieval Poland (8th–13th/14th Century); According to Zooarchaeological Records; Wydawnictwo Uniwerstytetu Mikołaja Kopernika: Toruń, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczyk, J.; Kramarek, J.; Lasota, C. Badania na Ostrowie Tumskim we Wrocławiu w 1977 roku. Sil. Antiq. 1979, 21, 119–182. [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz, M.; Marcinkiewicz, K.; Piekalski, J. Plac Nowy Targ we Wrocławiu w świetle badań wykopaliskowych w latach 2010–2012. Archaeol. Hist. Pol. 2014, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, C.B. Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabney, J.; Knapp, M.; Glocke, I.; Gansauge, M.-T.; Weihmann, A.; Nickel, B.; Valdiosera, C.; García, N.; Pääbo, S.; Arsuaga, J.-L.; et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15758–15763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, 2010, t5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S. Target enrichment via DNA hybridization capture. In Ancient DNA: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, M.; Lindgreen, S.; Orlando, L. AdapterRemoval v2: Rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, I.; Stephen, G.; Bayer, M.; Cock, P.J.A.; Pritchard, L.; Cardle, L.; Shaw, P.D.; Marshall, D. Using Tablet for visual exploration of second-generation sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 2013, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsson, H.; Ginolhac, A.; Schubert, M.; Johnson, P.L.F.; Orlando, L. MapDamage2.0: Fast approximate Bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1682–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, S.; Matzke, N.J.; Reissmann, M.; Hofreiter, M. Whole mitochondrial genome sequencing of domestic horses reveals incorporation of extensive wild horse diversity during domestication. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J. Missing Data and the Design of Phylogenetic Analyses. J. Biomed. Inform. 2006, 39, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fages, A.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Germonpré, M.; Orlando, L. Horse males became over-represented in archaeological assemblages during the Bronze Age. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 31, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.-S.; Fan, L.; Shi, N.-N.; Ning, T.; Yao, Y.-G.; Murphy, R.W.; Wang, W.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-P. DomeTree: A canonical toolkit for mitochondrial DNA analyses in domesticated animals. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, M.; Pruvost, M.; Benecke, N.; Hofreiter, M.; Morales, A.; Reissmann, M.; Ludwig, A. Origin and history of mitochondrial DNA lineages in domestic horses. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.; Forster, P.; Levine, M.A.; Oelke, H.; Hurles, M.; Renfrew, C.; Weber, J.; Olek, K. Mitochondrial DNA and the Origins of the Domestic Horse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10905–10910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pycińska, N.; Cieślak, J. Wykorzystanie badań genetycznych w rekonstrukcji historii gatunku koń domowy. Przegląd Hod. 2024, 3, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Wu, Y.; Xiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, C.; Wu, C. Some maternal lineages of domestic horses may have origins in East Asia revealed with further evidence of mitochondrial genomes and HVR-1 sequences. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maroń, J. Legnica 1241; Bellona: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, W.E. The Battle of Legnica: The Mongol Devastation of Poland. JSTOR 2016, 5, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pankiewicz, A. Między centrum, zapleczem a szlakiem handlowym. Wymiana i obieg pieniężny w tzw. ośrodkach centralnych we wczesnym średniowieczu na przykładzie Wrocławia. Archeol. Pol. 2022, LXVII, 159–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, B.C. OxCal v4.4.2. Oxford. 2020. Available online: https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Myczkowski, K. Ogólne wyniki badań szczątków kostnych i skorup zwierzęcych z wczesnego średniowiecza, wydobytych na Ostrowie Tumskim we Wrocławiu w latach 1950–1957. Przegląd Archeol. 1960, 12, 150–171. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickrell, J.K.; Pritchard, J.K. Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; Sham, P.C. PLINK: A tool set for whole- genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 2688–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Lab ID | Site | Social Context | Chronology | Skeletal Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EQW001 | Opole-Ostrówek | stronghold | 10–12th c. | Skull |

| 2 | EQW002 | Wrocław-Nowy Targ | settlement | 11–early 13th c. | Skull |

| 3 | EQW003 | Czeladź Wielka | settlement | 9/10–13th c. | Skull |

| 4 | EQW004 | Wrocław-Ostrów Tumski | stronghold | 12/13th c. | Mandible |

| 5 | EQW006 | Wrocław-Ostrów Tumski | stronghold | 10–13th c. | Skull |

| 6 | EQW007 | Wrocław-Ostrów Tumski | stronghold | 12–13th c. | Skull |

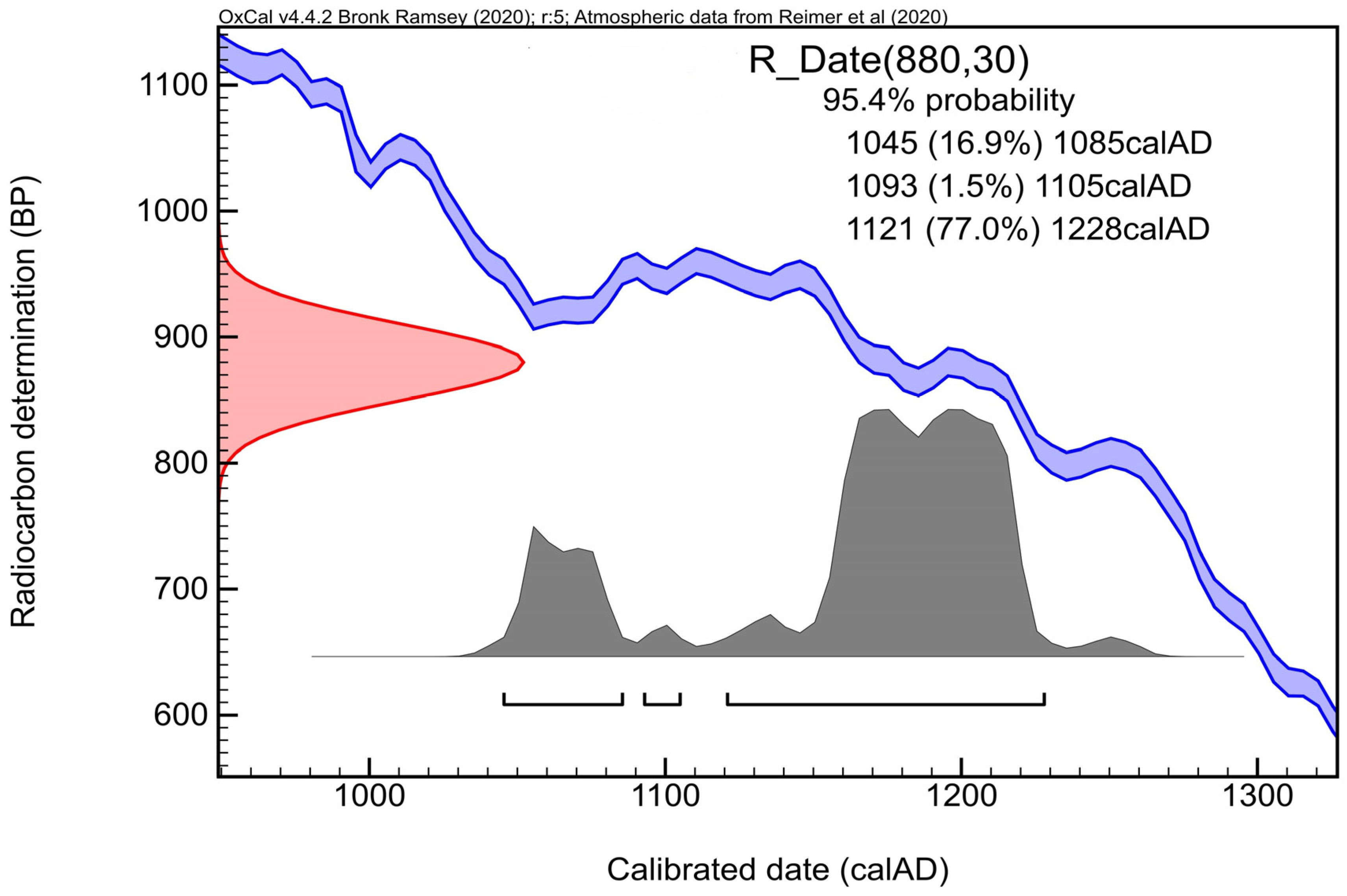

| 7 | EQW008 | Wrocław-Ostrów Tumski | stronghold | Early Medieval? | Mandible |

| 8 | EQW009 | Wrocław-Nowy Targ | settlement-town | 11–15th c. (18th c.) | Mandible |

| 9 | EQW010 | Wrocław-Nowy Targ | settlement-town | 11–15th c. (18th c.) | Mandible |

| No | Lab ID | # Reads | mtDNA Unique Reads | Mean mtDNA Coverage | mtDNA Bases Covered | mtDNA Hg | 5′/3′ DNA Damage | EquCab2 Unique Reads | Genetic Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

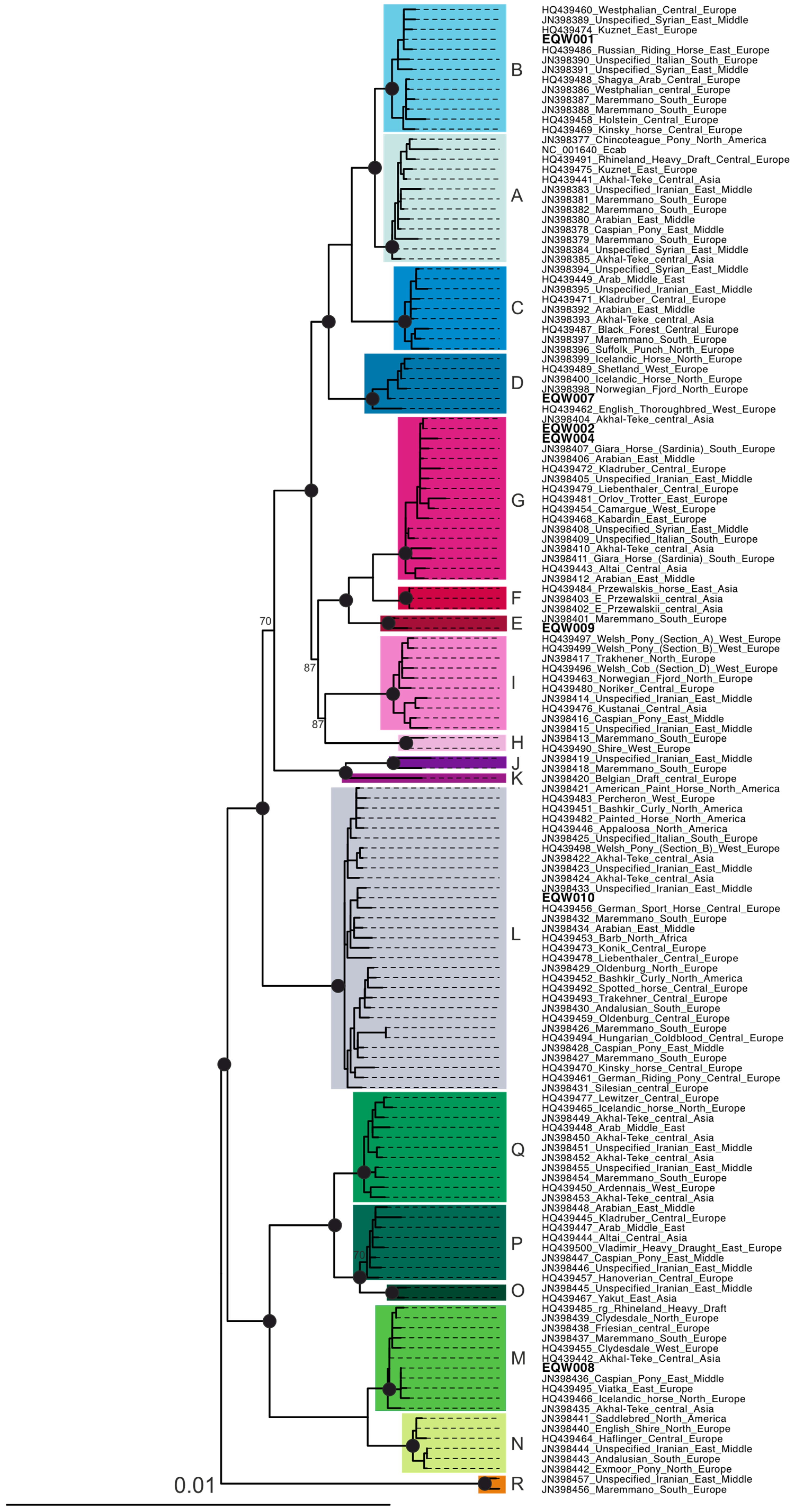

| 1 | EQW001 | 466,294 | 6795 | 35.13 | 16,557 | B1c | 0.16/0.17 | 15,796 | male |

| 2 | EQW002 | 1,351,970 | 11,702 | 69.68 | 16,550 | G1a_JN398404 | 0.17/0.16 | 489,608 | male |

| 3 | EQW003 | 2,153,524 | 91 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 266 | n.a. |

| 4 | EQW004 | 2,480,848 | 3346 | 17.98 | 16,284 | G1a | 0.09/0.11 | 225,032 | male |

| 5 | EQW006 | 1,134,316 | 69 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 6982 | female |

| 6 | EQW007 | 2,401,196 | 3625 | 20.68 | 16,026 | D1a2 | 0.15/0.16 | 41,255 | male |

| 7 | EQW008 | 4,045,447 | 3920 | 20.68 | 16,381 | M1b | 0.19/0.15 | 256,250 | male |

| 8 | EQW009 | 2,164,675 | 1779 | 14.86 | 14,871 | E | 0.16/0.17 | 211,223 | female |

| 9 | EQW010 | 3,199,186 | 1821 | 9.93 | 14,167 | L3a1 | 0.17/0.16 | 37,528 | inc. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pasicka, E.; Baca, M.; Popović, D.; Makowiecki, D.; Janeczek, M. Sequencing and Analysis of mtDNA Genomes from the Teeth of Early Medieval Horses in Poland. Genes 2026, 17, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010095

Pasicka E, Baca M, Popović D, Makowiecki D, Janeczek M. Sequencing and Analysis of mtDNA Genomes from the Teeth of Early Medieval Horses in Poland. Genes. 2026; 17(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010095

Chicago/Turabian StylePasicka, Edyta, Mateusz Baca, Danijela Popović, Daniel Makowiecki, and Maciej Janeczek. 2026. "Sequencing and Analysis of mtDNA Genomes from the Teeth of Early Medieval Horses in Poland" Genes 17, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010095

APA StylePasicka, E., Baca, M., Popović, D., Makowiecki, D., & Janeczek, M. (2026). Sequencing and Analysis of mtDNA Genomes from the Teeth of Early Medieval Horses in Poland. Genes, 17(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010095