Structural and Genomic Bases of Branching Traits in Spur-Type Apple: Insights from Morphology and Whole-Genome Resequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Morphometric Measurements

2.3. Anatomical and Histological Observation

2.4. Resequencing Variant Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

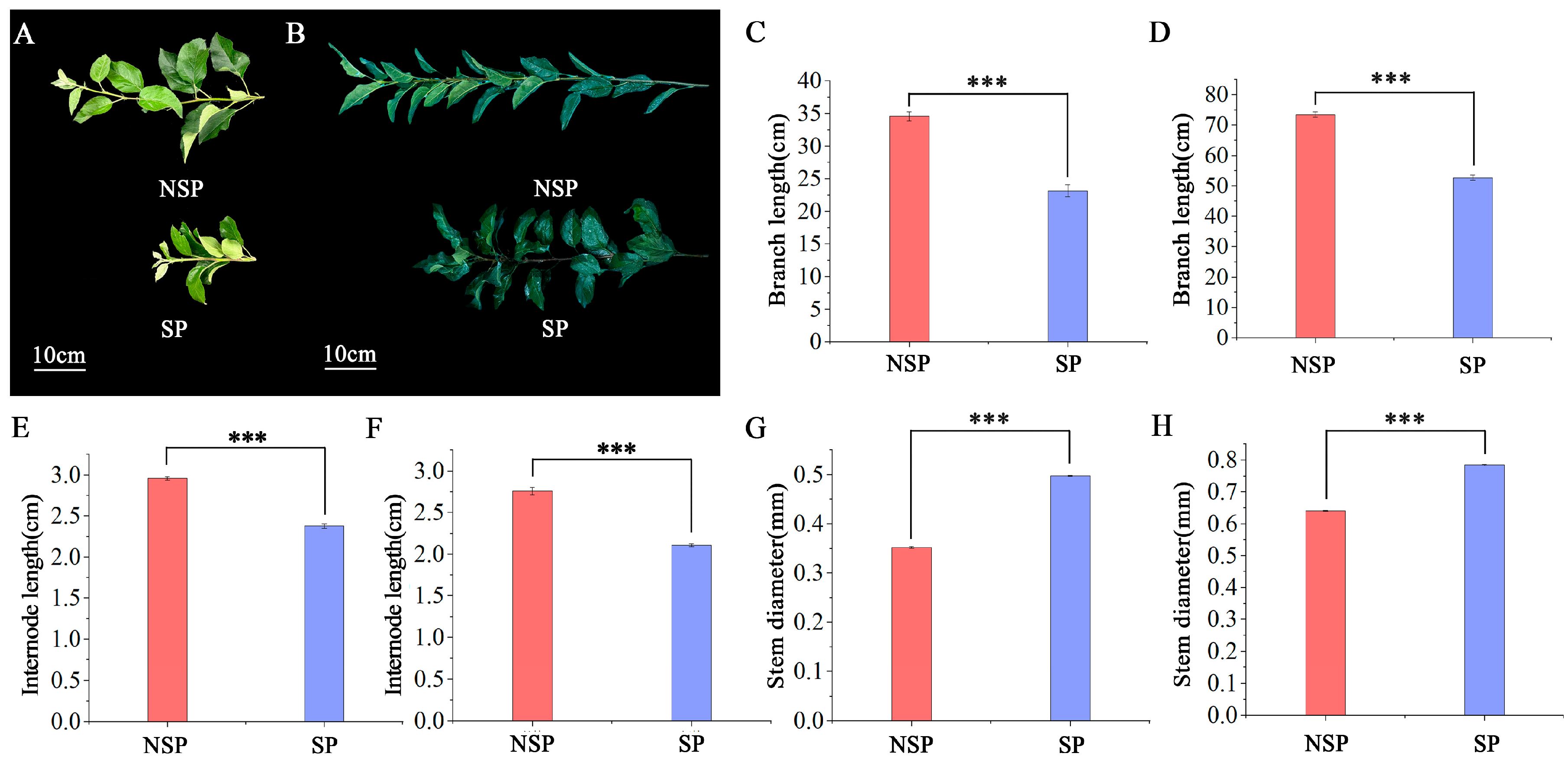

3.1. Morphometric Measurements of NSP and SP

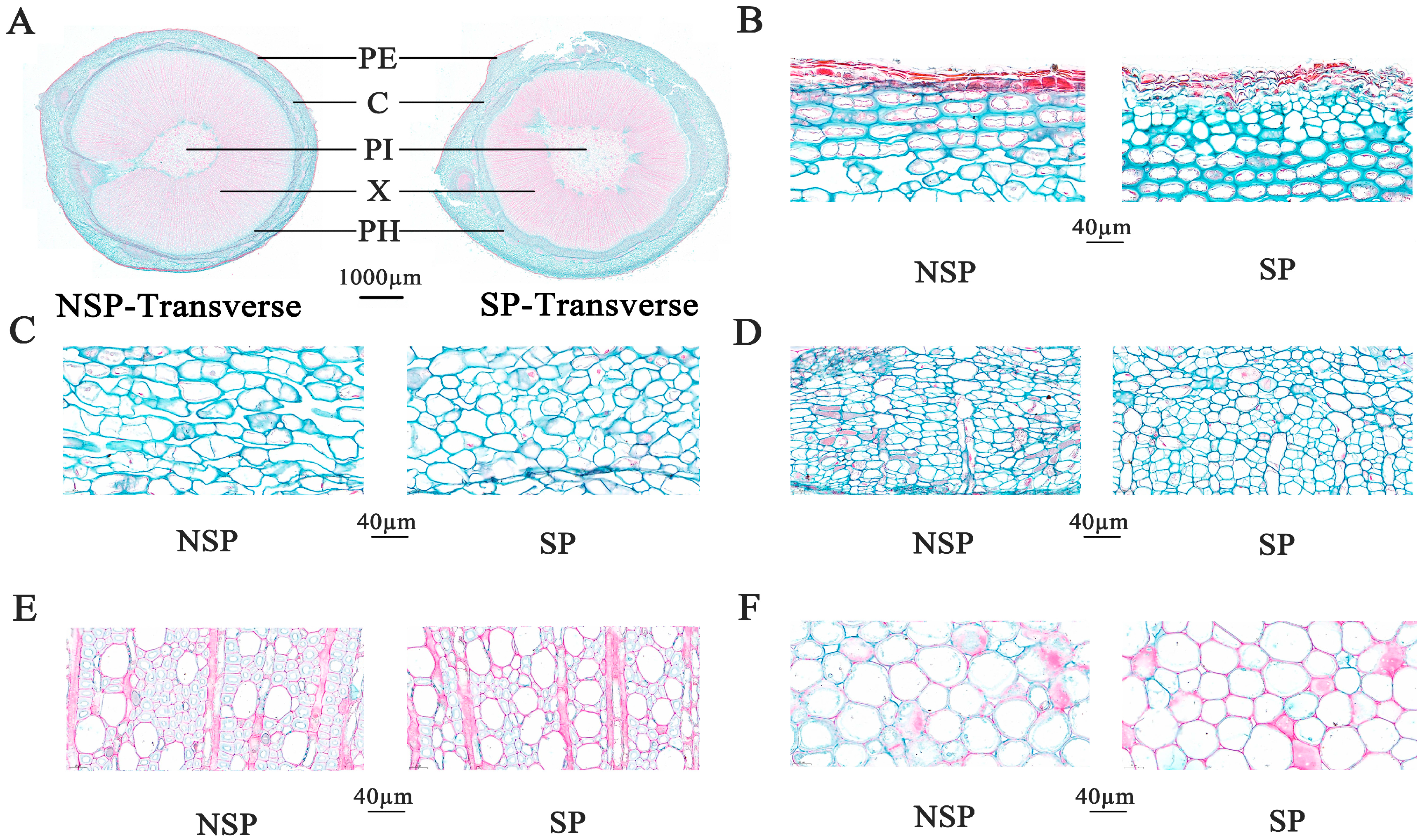

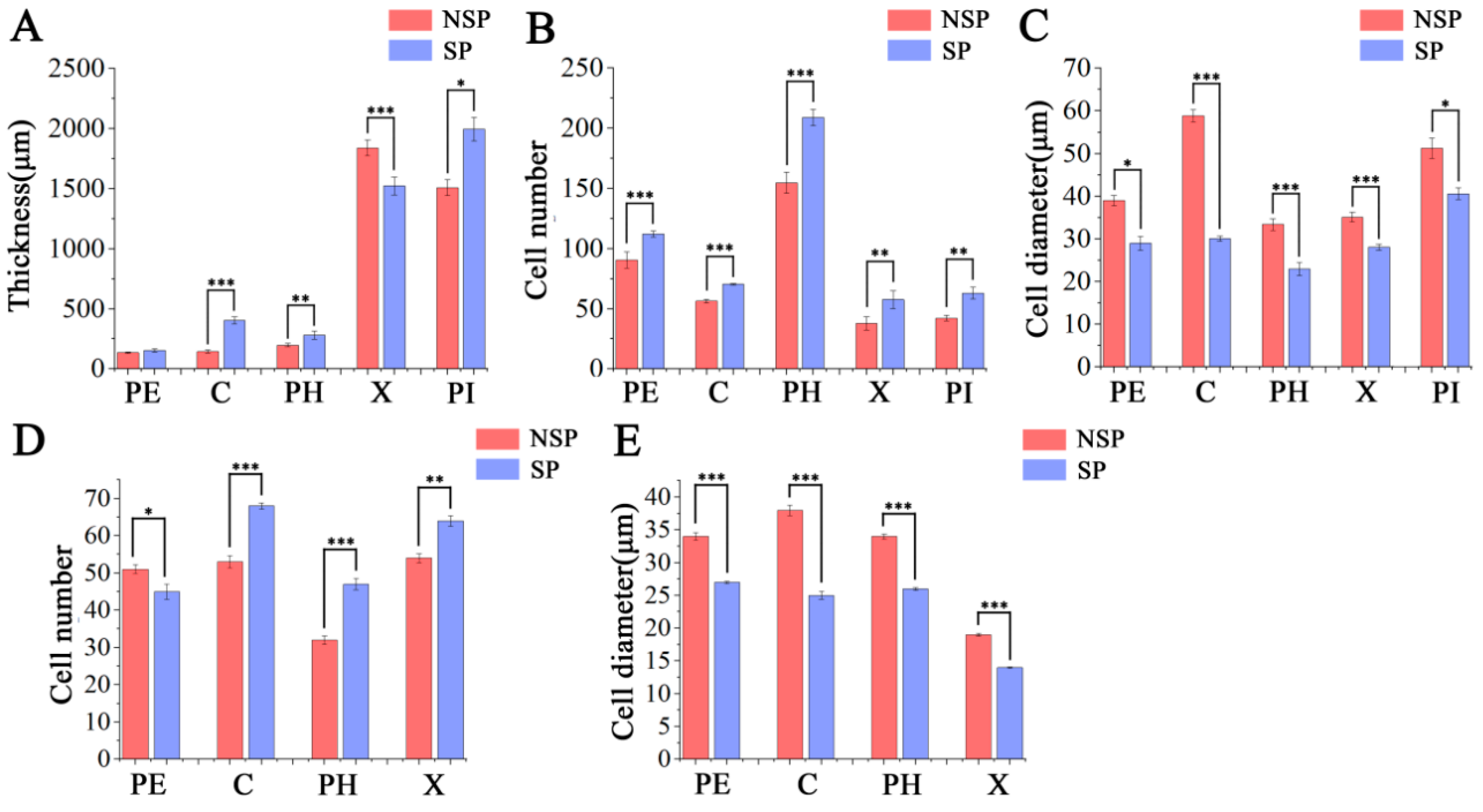

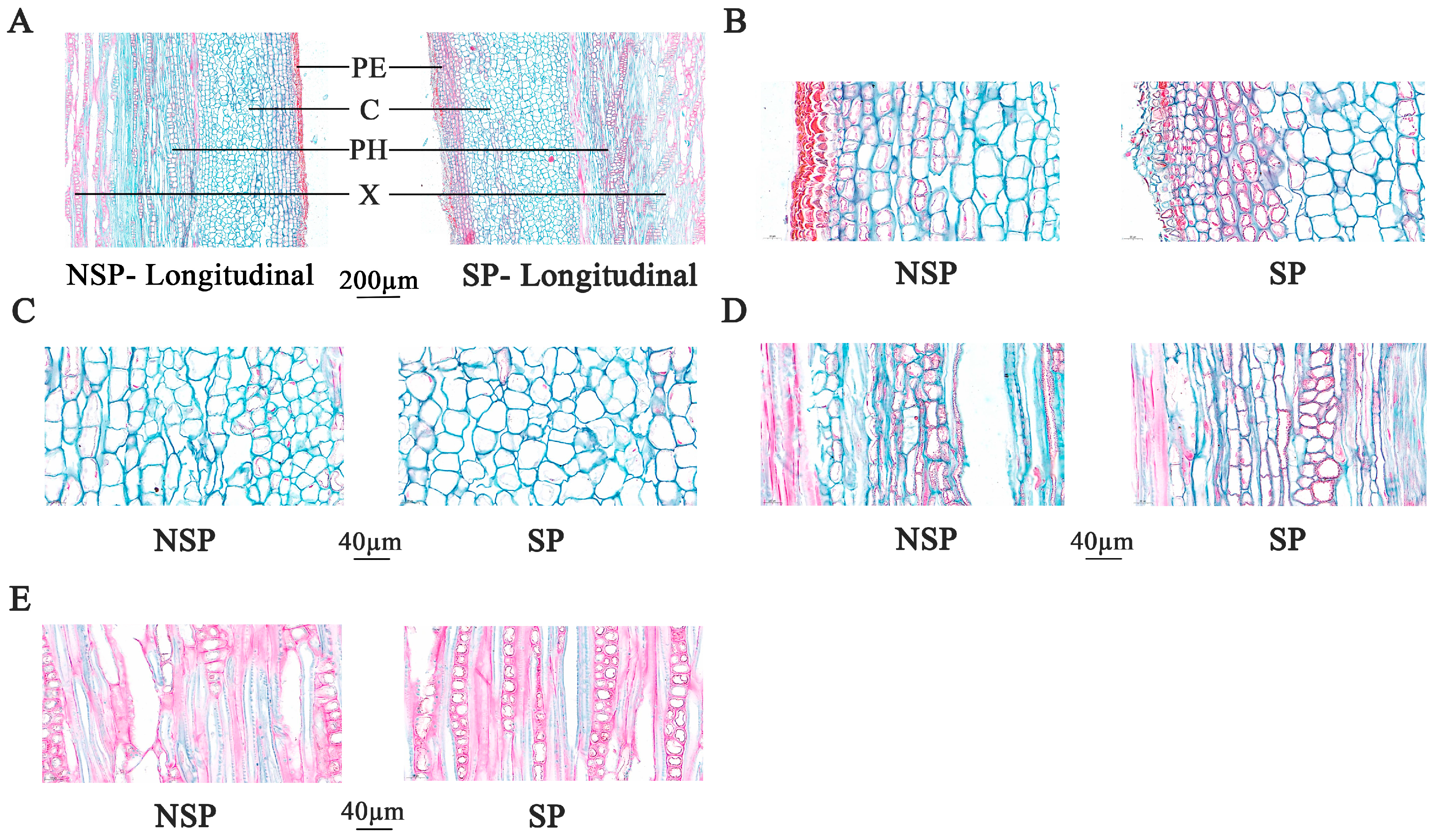

3.2. Anatomical Observation and Analysis

3.3. Variant Analysis of Resequencing Data in the Hybrid Progeny of NSP and SP

3.4. Detection and Annotation of SNPs

3.5. Detection and Annotation of InDels

3.6. Gene Ontology (GO) Annotation

3.7. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Anatomical Structure of Apple Branches Is Associated with Shoot Development

4.2. Plant Hormones Are the Main Factors Affecting Branching

4.3. Sucrose Signaling and Distribution Form the Material Foundation for Plant Branch Development

4.4. Multiple Metabolic Pathways Synergistically Modulate the Development of Plant Branching

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Smith, S.M.; Li, J. Genetic regulation of shoot architecture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, L.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Cao, D.; Tran, L.-S.P. Altering plant architecture to improve performance and resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1154–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ni, B.; Zeng, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, J. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Hormonal Control of Shoot Branching in Salix matsudana. Forests 2020, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, S.; Janssen, B.; Karunairetnam, S.; Wang, T.; Snowden, K.C. Modified CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE8 expression correlates with altered branching in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). New Phytol. 2010, 188, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebrom, T.H.; Brutnell, T.P.; Finlayson, S.A. Suppression of sorghum axillary bud outgrowth by shade, phyB and defoliation signalling pathways. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C.J. Auxin transport in the evolution of branching forms. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Janssen, B.J.; Snowden, K.C. The molecular and genetic regulation of shoot branching. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, N.; Roman, H.; Barbier, F.; Péron, T.; Huché-Thélier, L.; Lothier, J.; Demotes-Mainard, S.; Sakr, S. Light signaling in bud outgrowth and branching in plants. Plants 2014, 3, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Gui, S.; Wang, Y. Regulation of tillering and panicle branching in rice and wheat. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Beveridge, C.A. Roles for auxin, cytokinin, and strigolactone in regulating shoot branching. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 1929–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.-B.; Zhang, X.-S. Auxin–cytokinin interaction regulates meristem development. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariali, E.; Mohapatra, P.K. Hormonal regulation of tiller dynamics in differentially-tillering rice cultivars. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 53, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jiang, L.; Jameson, P.E. Expression patterns of Brassica napus genes implicate IPT, CKX, sucrose transporter, cell wall invertase, and amino acid permease gene family members in leaf, flower, silique, and seed development. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 5067–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameau, C.; Bertheloot, J.; Leduc, N.; Andrieu, B.; Foucher, F.; Sakr, S. Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Q.; Meng, D.; Wang, S. Effects of nitrogen and 6-benzylaminopurine on rice tiller bud growth and changes in endogenous hormones and nitrogen. Crop Sci. 2011, 51, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riefler, M.; Novak, O.; Strnad, M.; Schmülling, T. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development, and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.N.; Guo, H.Q.; Li, X.L.; Kong, L.Q. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR of Leymus chinensis in different tissues. Grassl. Sci. 2017, 34, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Yamagami, D.; Umehara, M.; Hanada, A.; Yoshida, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Yajima, S.; Kyozuka, J.; Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Matsuoka, M.; et al. Regulation of strigolactone biosynthesis by gibberellin signaling. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Bello, L.; Moritz, T.; López-Díaz, I. Silencing C19-GA 2-oxidases induces parthenocarpic development and inhibits lateral branching in tomato plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 5897–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Cheng, F.; Ma, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, D.; Han, M. Exogenous application of GA3 inactively regulates axillary bud outgrowth by influencing of branching-inhibitors and bud-regulating hormones in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Looney, N.E. Abscisic acid levels and genetic compaction in apple seedlings. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1977, 57, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Takahashi, M.; Kameoka, H.; Qin, R.; Shiga, T.; Kanno, Y.; Seo, M.; Ito, M.; Xu, G.; Kyozuka, J. Developmental analysis of the early steps in strigolactone-mediated axillary bud dormancy in rice. Plant J. 2019, 97, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Eggert, K.; Charnikhova, T.; Bouwmeester, H.; Schweizer, P.; Hajirezaei, M.R.; Seiler, C.; Sreenivasulu, N.; von Wirén, N.; et al. Abscisic acid influences tillering by modulation of strigolactones in barley. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3883–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, V.; Leyser, O. Hormonal control of shoot branching. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagalska, M.A.; Leyser, O. Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Xing, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ma, J.; Zhao, C.; Han, M.; Ren, X.; et al. MdKNOX15, a class I knotted-like transcription factor of apple, controls flowering and plant height by regulating GA levels through promoting the MdGA2ox7 transcription. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 185, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Qiang, D.; Zhun, W.; Xiangru, W.; Huiping, G.; Hengheng, Z.; Nianchang, P.; Xiling, Z.; Meizhen, S. Growth and nitrogen metabolism are associated with nitrogen-use efficiency in cotton genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Müller, N.; Borusak, S.; Schleheck, D.; Schink, B. Anaerobic dissimilatory phosphite oxidation, an extremely efficient concept of microbial electron economy. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, C.; Li, C.; Cao, X.-Y.; Sun, X.-D.; Bao, Q.-X.; Mu, X.-R.; Liu, C.-Y.; Loake, G.J.; Chen, H.-H.; Meng, L.-S. Long-distance transport of sucrose in source leaves promotes sink root growth by the EIN3-SUC2 module. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.-J.; Pommerrenig, B.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Keller, I. Interaction between sugar transport and plant development. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 288, 154073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerawitaya, C.; Supaibulwatana, K.; Tisarum, R.; Samphumphuang, T.; Chungloo, D.; Singh, H.P.; Cha-Um, S. Expression levels of nitrogen assimilation-related genes, physiological responses, and morphological adaptations of three indica rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica) genotypes subjected to nitrogen starvation conditions. Protoplasma 2023, 260, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, F.J.; Sandalio, L.M.; Van Breusegem, F. Understanding plant responses to stress conditions: Redox-based strategies. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5785–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.; Walters, L.A.; Cooper, A.M.; Olvera, J.G.; Rosas, M.A.; Rasmusson, A.G.; Escobar, M.A. Nitrate-regulated glutaredoxins control Arabidopsis primary root growth. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Paries, M.; Hobecker, K.; Gigl, M.; Dawid, C.; Lam, H.-M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Gutjahr, C. PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE transcription factors enable arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldie, T.; Hayward, A.; Beveridge, C.A. Axillary bud outgrowth in herbaceous shoots: How do strigolactones fit into the picture? Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 73, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, S.; Ma, Q.; Luo, Z. Physiological and full-length transcriptome analyses reveal the dwarfing regulation in trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L.). Plants 2023, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.-S. The interplay among PbNAC71, PbWAT1, and PbRNF217 reveals the secret behind dwarf pear trees. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, C.A.; Hadiarto, T.; Srinivasan, C.; Scorza, R.; Dardick, C. A brachytic dwarfism trait (dw) in peach trees is caused by a nonsense mutation within the gibberellic acid receptor PpeGID1c. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, K.; Honda, C. Molecular mechanisms regulating the columnar tree architecture in apple. Forests 2022, 13, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapins, K.O.; Fisher, D.V. Four natural spur-type mutants of Mclntosh apple. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1974, 54, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, I.J.; Ferree, D.C.; Schupp, J.R.; Dennis, F.G., Jr. Strain and Rootstock Effects on Spur Characteristics and Yield of Delicious’ Apple Strains. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1990, 115, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, E.; Lauri, P.E.; Regnard, J.L. Analyzing fruit tree architecture: Implications for tree management and fruit production. Hortic. Rev. 2006, 32, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, N.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sui, X.; Wang, S.; et al. Methylation of MdMYB1 locus mediated by RdDM pathway regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1736–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pang, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Huang, G.; Wei, S. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal that GA3ox regulates the dwarf trait in mango (Mangifera indica L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D.; Petersen, R.; Brauksiepe, B.; Braun, P.; Schmidt, E.R. The columnar mutation (“Co gene”) of apple (Malus × domestica) is associated with an integration of a Gypsy-like retrotransposon. Mol. Breed. 2014, 33, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Gao, X.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y.; Tong, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Kou, W.; Chang, C.; Foster, T.; et al. Genome sequencing of ‘Fuji’ apple clonal varieties reveals genetic mechanism of the spur-type morphology. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, H.; Guo, J.; Lu, L.; Mu, W.; Sun, J. Insertion of a solo LTR retrotransposon associates with spur mutations in ‘Red Delicious’ apple (Malus × domestica). Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tan, M.; Ma, J.; Cheng, F.; Li, K.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, D.; Xing, L.; Ren, X.; et al. Molecular mechanism of MdWUS2–MdTCP12 interaction in mediating cytokinin signaling to control axillary bud outgrowth. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4822–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Han, D. BWA-MEME: BWA-MEM emulated with a machine learning approach. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2404–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Cong, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Hao, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Integrated physiological and transcriptomic analyses uncover mechanisms regulating axillary bud outgrowth in apple. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, Q.; Wu, H.; Xiang, C.; Wang, J. DNL1, encodes cellulose synthase-like D4, is a major QTL for plant height and leaf width in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 457, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Su, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lv, H. Morphological, transcriptomics and phytohormone analysis shed light on the development of a novel dwarf mutant of cabbage (Brassica oleracea). Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, X.-F.; Zhao, L.-L.; Huang, L.-J.; Wang, P.-C. Morphological, transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of Sophora davidii mutants for plant height. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, N.; Tang, H.; Gong, B.; Shi, Q. Shoot branching regulation and signaling. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 92, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, M.; Brini, F.; Sharma, A.; Landi, M. Role of jasmonic acid in plants: The molecular point of view. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1471–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liang, C.; Qiu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yin, J.; Ma, C.; Cui, Z.; et al. Jasmonic acid negatively regulates branch growth in pear. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1105521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghi, L.; Kang, J.; Ko, D.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. The role of ABCG-type ABC transporters in phytohormone transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Luo, F.; Wu, D.; Zhang, X.; Lou, M.; Shen, D.; Yan, M.; Mao, C.; Fan, X.; Xu, G.; et al. OsPIN9, an auxin efflux carrier, is required for the regulation of rice tiller bud outgrowth by ammonium. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rongen, M.; Bennett, T.; Ticchiarelli, F.; Leyser, O. Connective auxin transport contributes to strigolactone-mediated shoot branching control independent of the transcription factor BRC1. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, M.; Schuetz, M.; Lin, B.S.P.; Chanis, C.; Hamberger, B.; Western, T.L.; Ehlting, J.; Samuels, A.L. ABC transporters coordinately expressed during lignification of Arabidopsis stems include a set of ABCBs associated with auxin transport. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2063–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Li, C.; Jiang, X.; Gai, Y. Transcriptomic insights into functions of LkABCG36 and LkABCG40 in Nicotiana tabacum. Plants 2023, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Sheen, J.; Müller, B. Cytokinin signaling networks. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Kang, J.; Kiba, T.; Park, J.; Kojima, M.; Do, J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kwon, M.; Endler, A.; Song, W.-Y.; et al. Arabidopsis ABCG14 is essential for the root-to-shoot translocation of cytokinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7150–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Essemine, J.; Pang, X.; Chen, H.; Cai, W. Exogenous application of abscisic acid to shoots promotes primary root cell division and elongation. Plant Sci. 2020, 292, 110385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretzschmar, T.; Kohlen, W.; Sasse, J.; Borghi, L.; Schlegel, M.; Bachelier, J.B.; Reinhardt, D.; Bours, R.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Martinoia, E. A petunia ABC protein controls strigolactone-dependent symbiotic signalling and branching. Nature 2012, 483, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, Q.; Yan, J.; Sun, K.; Liang, Y.; Jia, M.; Meng, X.; Fang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jing, Y.; et al. ζ-Carotene isomerase suppresses tillering in rice through the coordinated biosynthesis of strigolactone and abscisic acid. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1784–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Canam, T.; Kang, K.-Y.; Ellis, D.D.; Mansfield, S.D. Over-expression of an arabidopsis family A sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) gene alters plant growth and fibre development. Transgenic Res. 2008, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashida, Y.; Aoki, N.; Kawanishi, H.; Okamura, M.; Ebitani, T.; Hirose, T.; Yamagishi, T.; Ohsugi, R. A near isogenic line of rice carrying chromosome segments containing OsSPS1 of Kasalath in the genetic background of Koshihikari produces an increased spikelet number per panicle. Field Crop. Res. 2013, 149, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, X.; He, J.; Dong, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Ren, R.; Yang, T. Comparative transcriptome analysis and genetic dissection of vegetative branching traits in foxtail millet (Setaria italica). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.-J.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.-N.; Su, J.-P.; Sun, L.-J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, D.-F.; Chen, X.-W. Os4BGlu14, a monolignol β-Glucosidase, negatively affects seed longevity by influencing primary metabolism in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Yan, X. A novel Beta-glucosidase gene for plant type was identified by genome-wide association study and gene co-expression analysis in widespread Bermudagrass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, S.; Luo, X.; Cao, Y. Overexpression of the bamboo sucrose synthase gene (BeSUS5) improves cellulose production, cell wall thickness and fiber quality in transgenic poplar. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, K.; Lei, B.; Zhou, J.; Guo, T.; An, X. Altered sucrose metabolism and plant growth in transgenic Populus tomentosa with altered sucrose synthase PtSS3. Transgenic Res. 2020, 29, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Qi, X. Biosynthesis of triterpenoids in plants: Pathways, regulation, and biological functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 85, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umehara, M.; Hanada, A.; Yoshida, S.; Akiyama, K.; Arite, T.; Takeda-Kamiya, N.; Magome, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Shirasu, K.; Yoneyama, K.; et al. Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 2008, 455, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasbery, J.M.; Shan, H.; LeClair, R.J.; Norman, M.; Matsuda, S.P.T.; Bartel, B. Arabidopsis thaliana squalene epoxidase 1 is essential for root and seed development. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 17002–17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, K.; Manners, J.M. Jasmonate signaling: Toward an integrated view. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolman, B.K.; Martinez, N.; Millius, A.; Adham, A.R.; Bartel, B. Identification and characterization of Arabidopsis indole-3-butyric acid response mutants defective in novel peroxisomal enzymes. Genetics 2008, 180, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahas, Z.; Ticchiarelli, F.; van Rongen, M.; Dillon, J.; Leyser, O. The activation of Arabidopsis axillary buds involves a switch from slow to rapid committed outgrowth regulated by auxin and strigolactone. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Haslam, T.M.; Sonntag, A.; Molina, I.; Kunst, L. Functional overlap of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, M.W.; Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. K+ transport in plants: Physiology and molecular biology. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, Q.; Qi, K.; Xie, Z.; Yin, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, R.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Identification of Shaker K+ channel family members in Rosaceae and a functional exploration of PbrKAT1. Planta 2019, 250, 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K.; Levchenko, V.; Fromm, J.; Geiger, D.; Steinmeyer, R.; Lautner, S.; Ache, P.; Hedrich, R. The poplar K+ channel KPT1 is associated with K+ uptake during stomatal opening and bud development. Plant J. 2004, 37, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, S. Plastoquinone and ubiquinone in plants: Biosynthesis, physiological function and metabolic engineering. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhnova, N.A.; Gerashchenkov, G.A. Hormonal status of tobacco variety Samsun NN exposed to synthetic coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone 50) and TMV infection. Biol. Bull. 2006, 33, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.; Qiu, J.-L.; Wu, J. Isochorismate synthase is required for phylloquinone, but not salicylic acid biosynthesis in rice. aBIOTECH 2024, 5, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wu, A.; Liu, L. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 ortholog PagAS1a promotes xylem development and plant growth in Populus. For. Res. 2025, 5, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Guo, W.; Hu, M.X.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhou, G.K.; Chai, G.H.; Zhao, S.T.; Lu, M.Z. PagERF81 regulates lignin biosynthesis and xylem cell differentiation in poplar. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Houari, I.; Van Beirs, C.; Arents, H.E.; Han, H.; Chanoca, A.; Opdenacker, D.; Pollier, J.; Storme, V.; Steenackers, W.; Quareshy, M.; et al. Seedling developmental defects upon blocking CINNAMATE-4-HYDROXYLASE are caused by perturbations in auxin transport. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2275–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample ID | Clean Bases (bp) | Clean Reads | Clean GC (%) | Clean Q30 (%) | Mapped Ratio (%) | Real Depth × | Coverage (%) (≥1×) | Coverage (%) (≥4×) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | 7,422,980,792 | 24,635,645 | 38.68 | 91.10 | 98.05 | 12.23 | 83.91 | 75.90 |

| SP | 8,212,655,150 | 27,259,601 | 38.79 | 92.39 | 97.58 | 13.62 | 82.94 | 75.71 |

| Sample ID | SNP Number | Transition | Transversion | Ti/Tv | Homozygosity | Heterozygosity | Het- Ratio % | High | Moderate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | 2,712,688 | 1,858,683 | 858,033 | 2.17 | 2,291,280 | 2,097,484 | 77.32 | 2775 | 78,829 |

| SP | 3,538,106 | 2,434,493 | 1,110,116 | 2.19 | 1,465,862 | 2,136,474 | 60.38 | 3558 | 100,030 |

| Sample ID | CDS SNPs Number | Missense Variant | Synonymous Variant | Stop Gained | Stop Lost | Start Lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | 144,306 | 78,829 | 63,396 | 1487 | 323 | 271 |

| SP | 182,597 | 100,030 | 79,834 | 1978 | 415 | 340 |

| Sample | Total | Insertion | Deletion | Homo | Het | High | Moderate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | 319,195 | 148,304 | 170,891 | 78,031 | 241,164 | 5151 | 2781 |

| SP | 415,521 | 194,940 | 220,581 | 166,195 | 249,326 | 6762 | 3534 |

| Sample ID | Conservative In-Frame Deletion | Conservative In-Frame Insertion | Disruptive In-Frame Deletion | Disruptive In-Frame Insertion | Frameshift Variant | Stop Gained | Stop Lost | Start Lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | 481 | 611 | 880 | 614 | 4817 | 196 | 79 | 139 |

| SP | 645 | 772 | 1090 | 787 | 6323 | 249 | 88 | 169 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhu, B.; Jia, L.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X. Structural and Genomic Bases of Branching Traits in Spur-Type Apple: Insights from Morphology and Whole-Genome Resequencing. Genes 2026, 17, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010096

Wang H, Chen D, Zhao G, Zhang D, Liu X, Zhu B, Jia L, Zhao T, Zhang C, Zhang X. Structural and Genomic Bases of Branching Traits in Spur-Type Apple: Insights from Morphology and Whole-Genome Resequencing. Genes. 2026; 17(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Han, Dongmei Chen, Guodong Zhao, Da Zhang, Xin Liu, Bowei Zhu, Linguang Jia, Tongsheng Zhao, Chaohong Zhang, and Xinsheng Zhang. 2026. "Structural and Genomic Bases of Branching Traits in Spur-Type Apple: Insights from Morphology and Whole-Genome Resequencing" Genes 17, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010096

APA StyleWang, H., Chen, D., Zhao, G., Zhang, D., Liu, X., Zhu, B., Jia, L., Zhao, T., Zhang, C., & Zhang, X. (2026). Structural and Genomic Bases of Branching Traits in Spur-Type Apple: Insights from Morphology and Whole-Genome Resequencing. Genes, 17(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010096