Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons Regulate Sleep Deprivation and Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Brain Region | Context/Trigger | Function of Sst Neurons | Effect on Sleep/Wakefulness | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neocortex | Normal Sleep | Generates “OFF state” of slow waves | SWA ↑, NREM sleep time ↑ | [9] |

| Hippocampus | Sleep Deprivation | Inhibitory gate for memory consolidation | Inhibits sleep function (memory) | [3] |

| Central Amygdala (CeA) | Acute Stress | Mediates stress-induced arousal | Sleep latency ↑, Arousal ↑ | [4] |

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) Projection | Sleep Deprivation (Homeostatic Response) | Coordinates recovery sleep | Induces preparatory behavior and recovery NREM sleep | [5] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Expression Profiles

2.2. Tensor

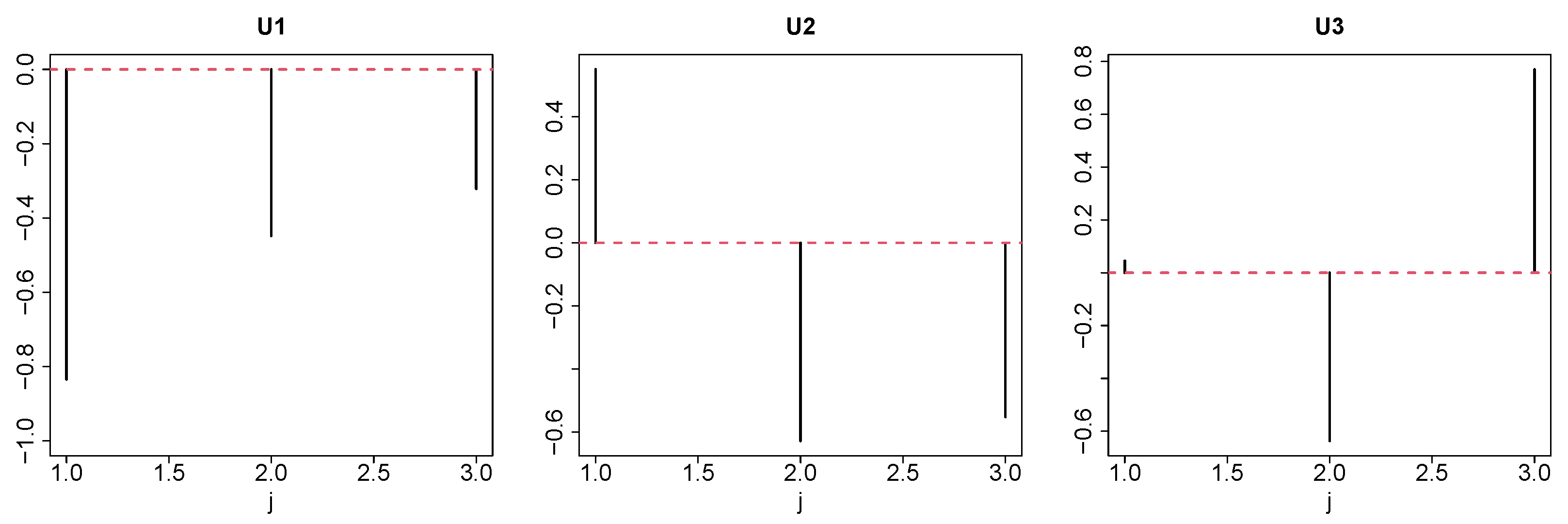

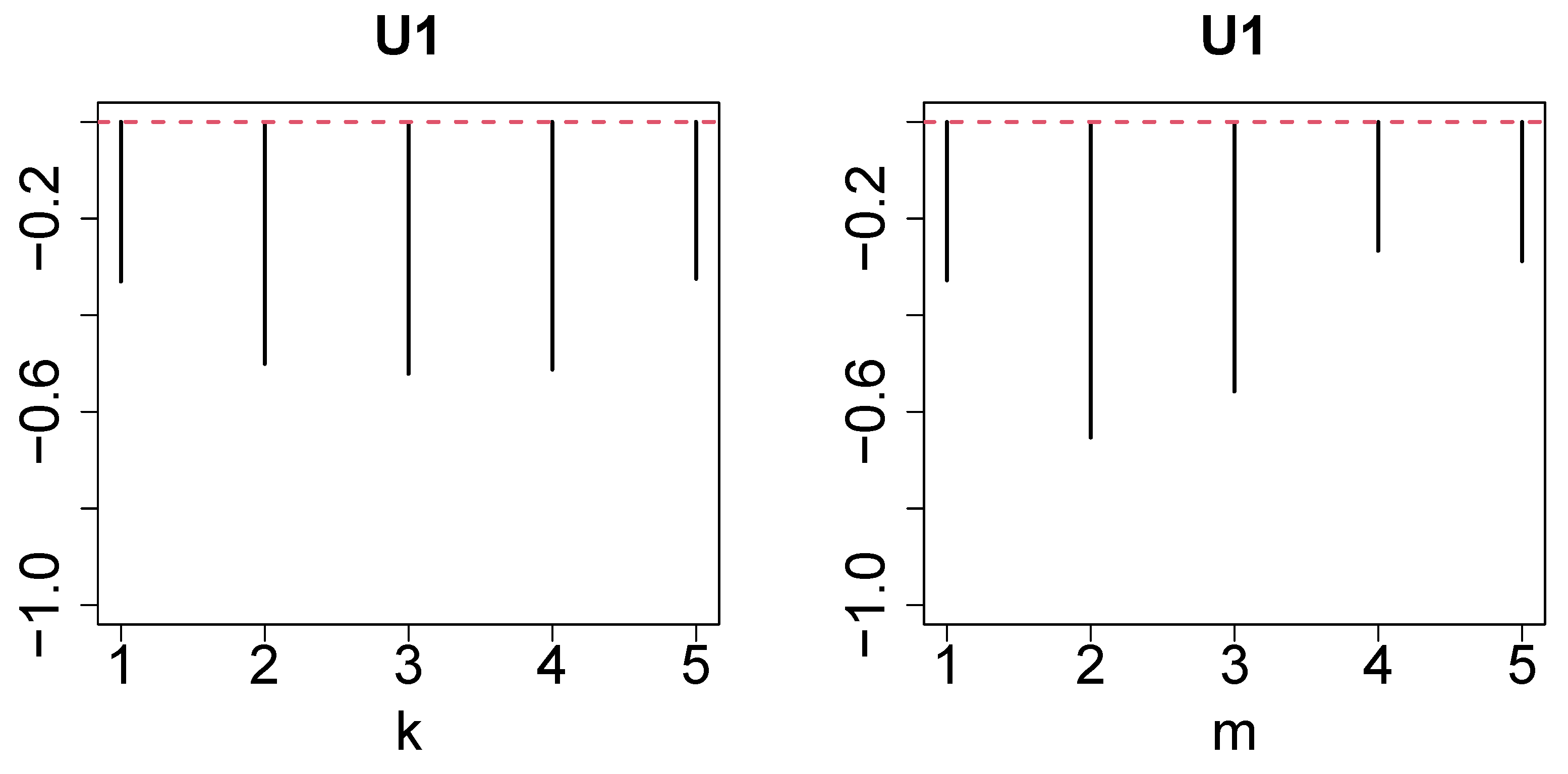

2.3. Tensor Decomposition

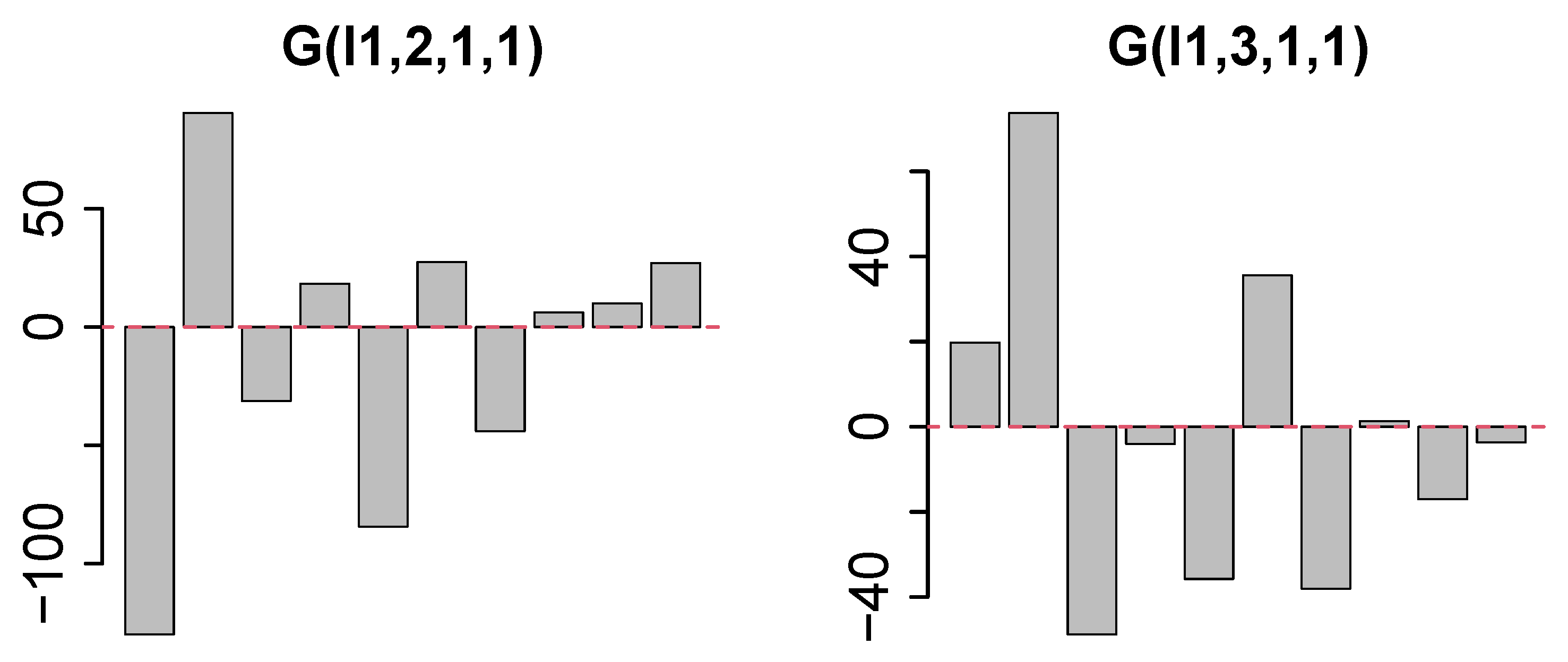

2.4. Gene Selection

- Since the gene expression ought to be distinct between controls and others, should be distinct from and/or .

- Since the gene expression should not be distinct between replicates, should be constant as well as possible.

- Since we did not pre-judge dependence upon time, we overlooked the dependence of upon m.

2.5. AlphaGenome

2.5.1. Conversion to Genomic Regions

2.5.2. Upload to AlphaGenome and Retrieving Features

2.5.3. The Selection of Top Ranked Genes

2.6. Alternative Gene Expression Profiles

2.6.1. GSE33491 [12]

2.6.2. GSE78215 [13]

2.6.3. GSE144957 [14]

3. Results

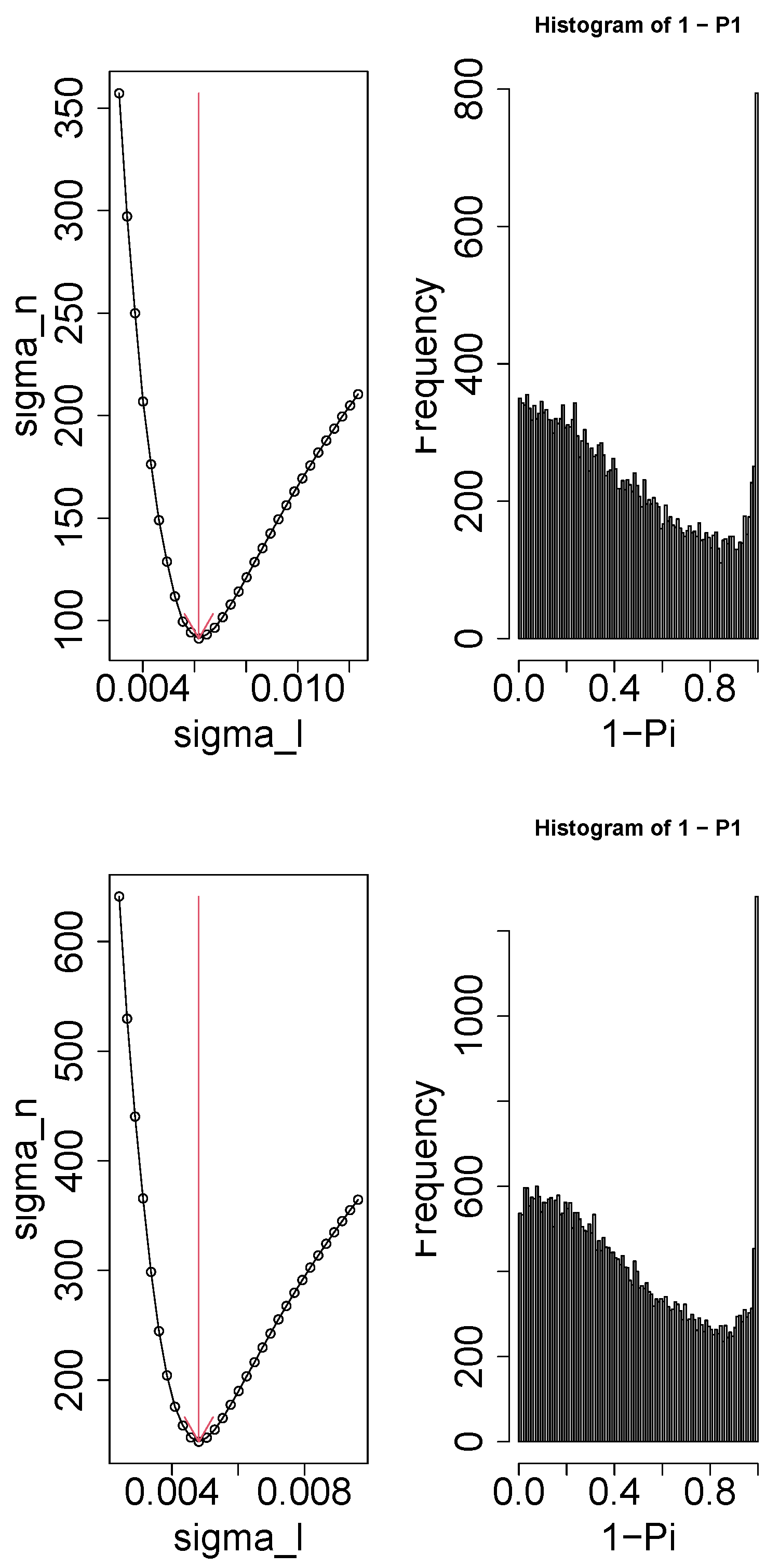

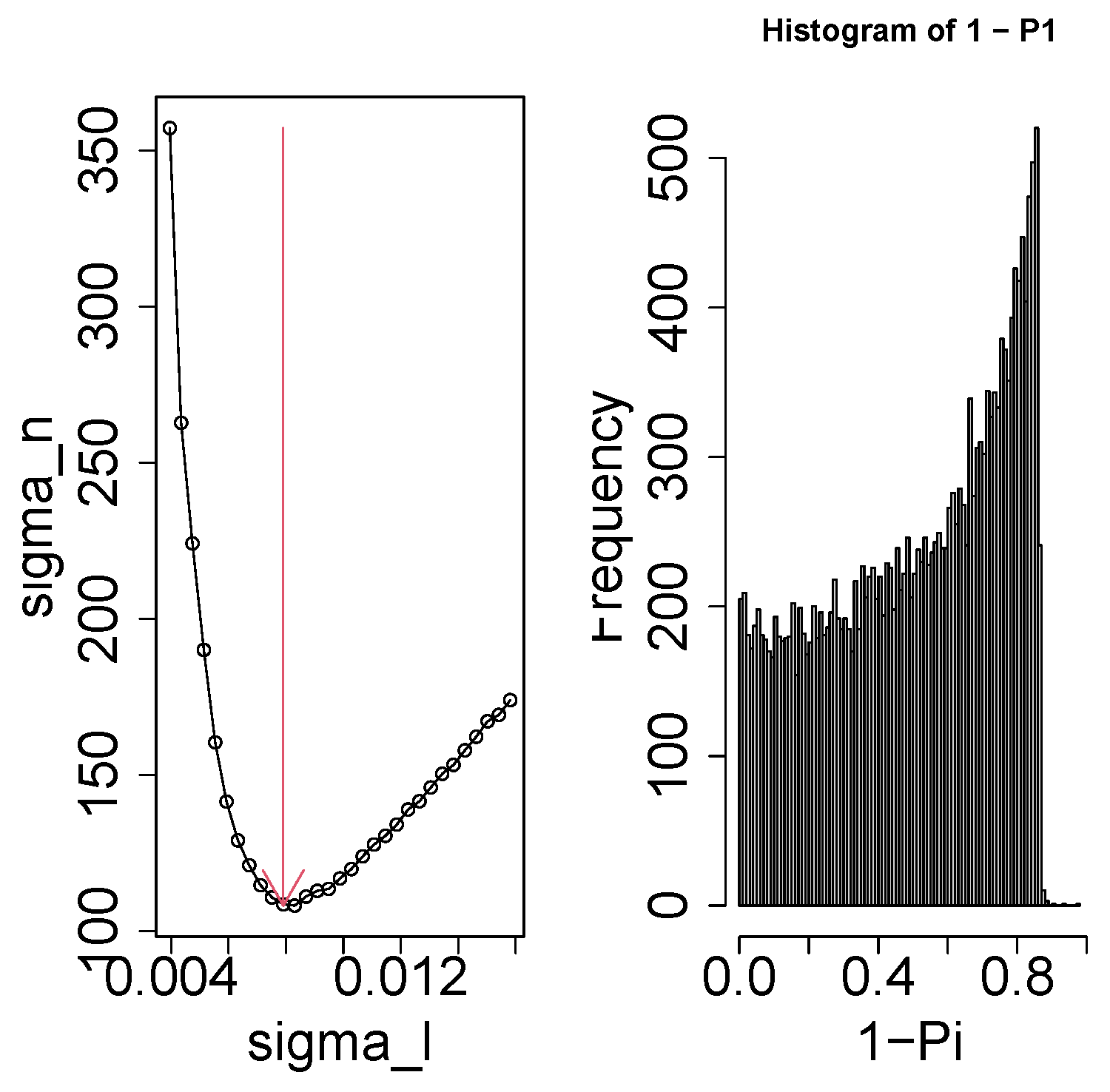

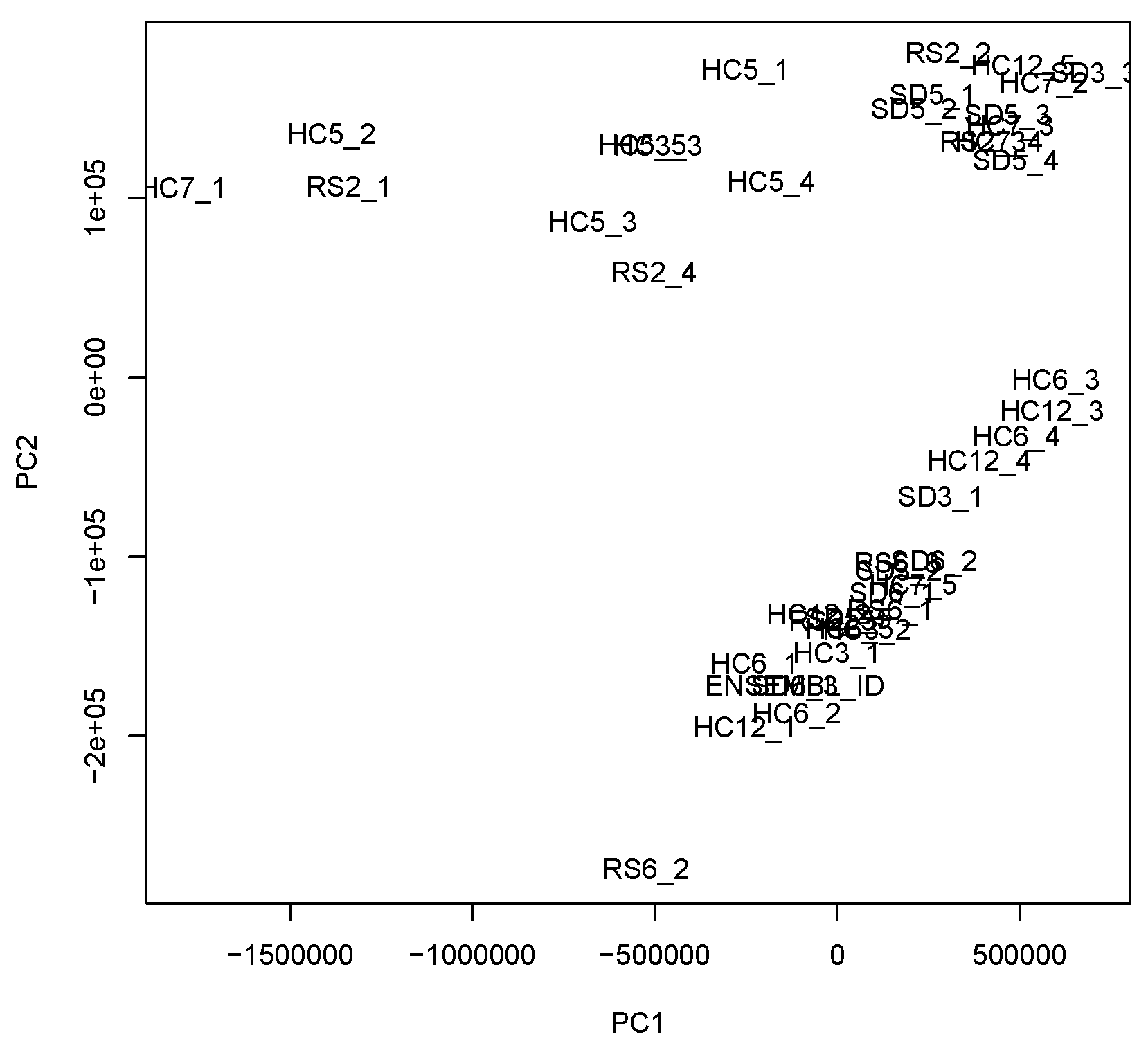

3.1. Gene Selection

3.2. Metascape

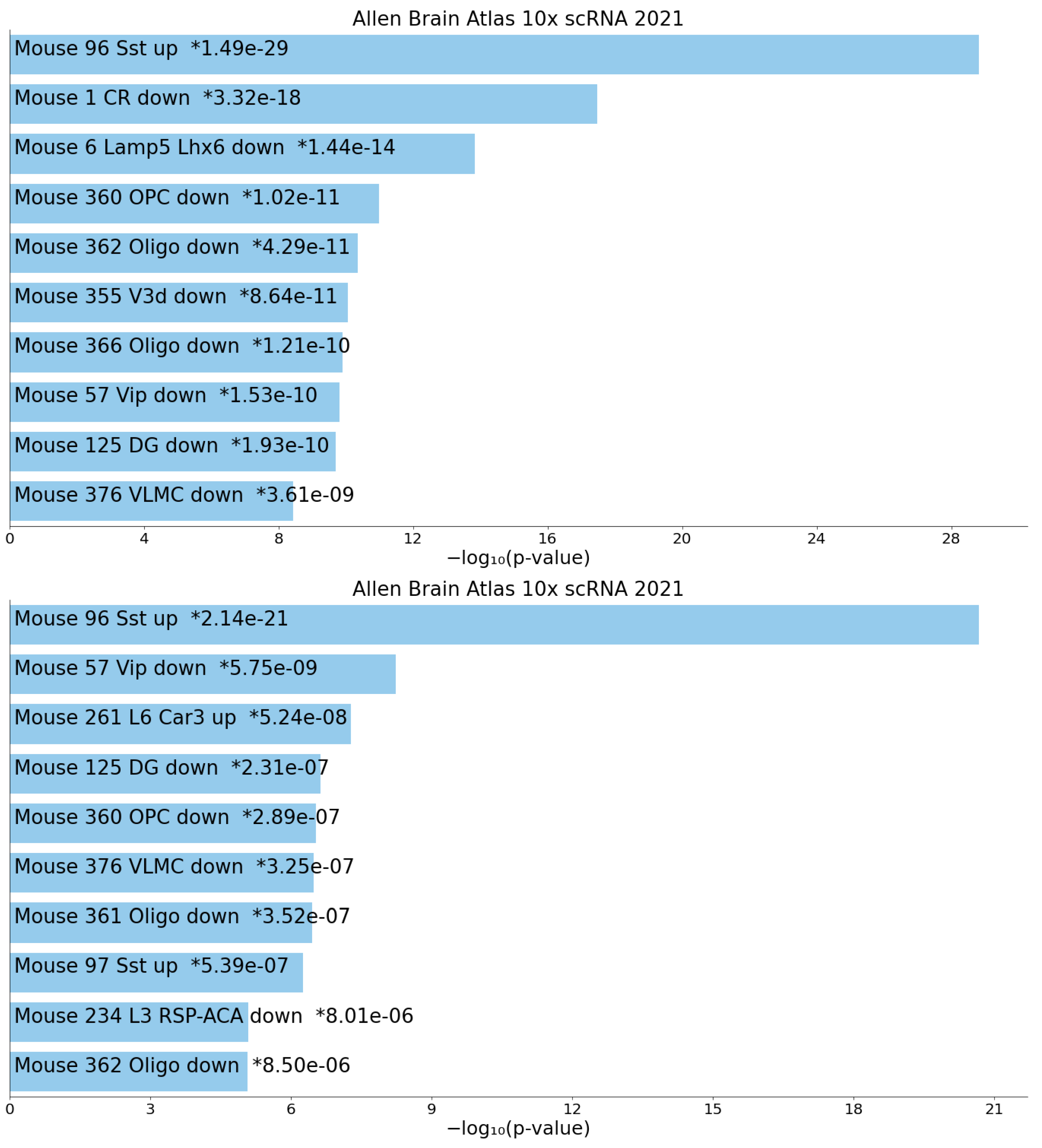

3.3. Enrichr

3.4. Alternative Gene Expression Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popescu, A.; Ottaway, C.; Ford, K.; Medina, E.; Patterson, T.W.; Ingiosi, A.; Hicks, S.C.; Singletary, K.; Peixoto, L. Transcriptional dynamics of sleep deprivation and subsequent recovery sleep in the male mouse cortex. Physiol. Genom. 2025, 57, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, Y.h. Unsupervised Feature Extraction Applied to Bioinformatics: A PCA Based and TD Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, J.; Wang, L.; Kuhn, F.R.; Kodoth, V.; Ma, J.; Martinez, J.D.; Raven, F.; Toth, B.A.; Balendran, V.; Medina, A.V.; et al. Sleep loss drives acetylcholine- and somatostatin interneuron–mediated gating of hippocampal activity to inhibit memory consolidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019318118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Huang, S.X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.S.; Huang, D.Y.; Huang, K.Q.; Huang, Z.X.; Nian, L.W.; Li, J.L.; Chen, L.; et al. Central amygdala somatostatin neurons modulate stress-induced sleep-onset insomnia. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossell, K.; Yu, X.; Giannos, P.; Soto, B.A.; Nollet, M.; Yustos, R.; Miracca, G.; Vicente, M.; Miao, A.; Hsieh, B.; et al. Somatostatin neurons in prefrontal cortex initiate sleep-preparatory behavior and sleep via the preoptic and lateral hypothalamus. Nat. Neurosci. Correction in Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 1570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02003-3.. 2023, 26, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tossell, K.; Yu, X.; Soto, B.A.; Vicente, M.; Miracca, G.; Giannos, P.; Miao, A.; Hsieh, B.; Ma, Y.; Yustos, R.; et al. Sleep deprivation triggers somatostatin neurons in prefrontal cortex to initiate nesting and sleep via the preoptic and lateral hypothalamus. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Tsujino, N.; Hasegawa, E.; Akashi, K.; Abe, M.; Mieda, M.; Sakimura, K.; Sakurai, T. GABAergic neurons in the preoptic area send direct inhibitory projections to orexin neurons. Front. Neural Circuits 2013, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, F.; Medina, A.V.; Schmidt, K.; He, A.; Vankampen, A.A.; Balendran, V.; Aton, S.J. Brief sleep disruption alters synaptic structures among hippocampal and neocortical somatostatin-expressing interneurons. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.M.; Peelman, K.; Bellesi, M.; Marshall, W.; Cirelli, C.; Tononi, G. Role of Somatostatin-Positive Cortical Interneurons in the Generation of Sleep Slow Waves. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 9132–9148, Correction in J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 10770. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2902-17.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Bioconductor Dev Team. BSgenome.Mmusculus.UCSC.mm39: Full Genome Sequences for Mus Musculus (UCSC Genome mm39, Based on GRCm39). R Package Version 1.4.3. 2021. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/BSgenome.Mmusculus.UCSC.mm39.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- DeepMind, G. AlphaGenome. 2025. Available online: https://deepmind.google.com/science/alphagenome/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Hinard, V.; Mikhail, C.; Pradervand, S.; Curie, T.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Auwerx, J.; Franken, P.; Tafti, M. Key Electrophysiological, Molecular, and Metabolic Signatures of Sleep and Wakefulness Revealed in Primary Cortical Cultures. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 12506–12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, J.R.; Koberstein, J.N.; Watson, A.J.; Zapero, N.; Risso, D.; Speed, T.P.; Frank, M.G.; Peixoto, L. Removal of unwanted variation reveals novel patterns of gene expression linked to sleep homeostasis in murine cortex. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorness, T.E.; Kulkarni, A.; Rybalchenko, V.; Suzuki, A.; Bridges, C.; Harrington, A.J.; Cowan, C.W.; Takahashi, J.S.; Konopka, G.; Greene, R.W. An essential role for MEF2C in the cortical response to loss of sleep in mice. eLife 2020, 9, e58331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, N. Roles of Endoplasmic Reticulum and Energetic Stress in Disturbed Sleep. NeuroMol. Med. 2012, 14, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Aton, S.J. Perspective – ultrastructural analyses reflect the effects of sleep and sleep loss on neuronal cell biology. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimaru, H.; Matsumoto, J.; Setogawa, T.; Nishijo, H. Neuronal structures controlling locomotor behavior during active and inactive motor states. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 189, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.H.; Turki, T. L1 GABAergic neurones in the frontal cortex and L6 glutamatergic neurones in the prefrontal cortex use RHO GTPase to differentiate between unconsciousness states. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Bailey, A.; Kuleshov, M.V.; Clarke, D.J.B.; Evangelista, J.E.; Jenkins, S.L.; Lachmann, A.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Jagodnik, K.M.; et al. Gene Set Knowledge Discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, D. GABA receptors in brain development, function, and injury. Metab. Brain Dis. 2015, 30, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, O. Development of GABAergic Interneurons in the Human Cerebral Cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2025, 61, e70136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, R.; Lee, S.; Rudy, B. GABAergic Interneurons in the Neocortex: From Cellular Properties to Circuits. Neuron 2016, 91, 260–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Ciecko, J.; Barth, A.L. Somatostatin-expressing neurons in cortical networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguz-Lecznar, M.; Dobrzanski, G.; Kossut, M. Somatostatin and Somatostatin-Containing Interneurons—From Plasticity to Pathology. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, C.; Prevot, T.D.; Misquitta, K.; Knutson, D.E.; Li, G.; Mondal, P.; Cook, J.M.; Banasr, M.; Sibille, E. Behavioral Deficits Induced by Somatostatin-Positive GABA Neuron Silencing Are Rescued by Alpha 5 GABA-A Receptor Potentiation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyltjens, I.; Arckens, L. The Current Status of Somatostatin-Interneurons in Inhibitory Control of Brain Function and Plasticity. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 8723623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.A.; Fleming, G.; Williams, C.R.O.; Teixeira, C.M.; Smiley, J.F.; Saito, M. Somatostatin neuron contributions to cortical slow wave dysfunction in adult mice exposed to developmental ethanol. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1127711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, M.R.; Atochin, D.N.; McNally, J.M.; McKenna, J.T.; Huang, P.L.; Strecker, R.E.; Gerashchenko, D. Somatostatin+/nNOS+ neurons are involved in delta electroencephalogram activity and cortical-dependent recognition memory. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avsec, Ž.; Latysheva, N.; Cheng, J.; Novati, G.; Taylor, K.R.; Ward, T.; Bycroft, C.; Nicolaisen, L.; Arvaniti, E.; Pan, J.; et al. AlphaGenome: Advancing regulatory variant effect prediction with a unified DNA sequence model. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.h.; Turki, T. Tensor-Decomposition-Based Unsupervised Feature Extraction in Single-Cell Multiomics Data Analysis. Genes 2021, 12, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.h.; Turki, T. Adapted tensor decomposition and PCA based unsupervised feature extraction select more biologically reasonable differentially expressed genes than conventional methods. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| m | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HC3 () | SD3 () | — |

| 2 | HC5 () | SD5 () | RS2 () |

| 3 | HC6 () | SD6 () | RS6 () |

| 4 | HC7 () | — | — |

| 5 | HC12 () | — | — |

| PC2 | PC3 | GO/REAC | Category | Description | Count | % | Log10(P) | Log10(q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◯ | R-MMU-72766 | REAC | Translation | 65 | 4.16 | −21.75 | −17.49 | |

| ◯ | ◯ | R-MMU-8953854 | REAC | Metabolism of RNA | 112 | 7.17 | −21.43 | −17.47 |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0016072 | GO BP | rRNA metabolic process | 59 | 3.77 | −15.85 | −12.54 |

| ◯ | GO:0061024 | GO BP | membrane organization | 119 | 7.61 | −15.08 | −11.82 | |

| ◯ | GO:0006351 | GO BP | DNA-templated transcription | 95 | 6.08 | −14.75 | −11.53 | |

| ◯ | R-MMU-199991 | REAC | Membrane Trafficking | 92 | 5.89 | −13.88 | −10.80 | |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0030705 | GO BP | cytoskeleton-dependent intracellular transport | 50 | 3.20 | −13.72 | −10.68 |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0006886 | GO BP | intracellular protein transport | 92 | 5.89 | −13.58 | −10.63 |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0006914 | GO BP | autophagy | 68 | 4.35 | −13.57 | −10.63 |

| ◯ | GO:0048858 | GO BP | cell projection morphogenesis | 95 | 6.08 | −13.12 | −10.24 | |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0022411 | GO BP | cellular component disassembly | 58 | 3.71 | −12.49 | −9.67 |

| ◯ | ◯ | R-MMU-6791226 | REAC | Major pathway of rRNA processing in the nucleolus and cytosol | 43 | 2.75 | −11.76 | −9.04 |

| ◯ | GO:0070848 | GO BP | response to growth factor | 91 | 5.82 | −10.63 | −7.95 | |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0007626 | GO BP | locomotory behavior | 55 | 3.52 | −10.60 | −7.93 |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0048193 | GO BP | Golgi vesicle transport | 53 | 3.39 | −9.98 | −7.34 |

| ◯ | GO:1903829 | GO BP | positive regulation of protein localization | 84 | 5.37 | −9.62 | −7.02 | |

| ◯ | GO:0034976 | GO BP | response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | 48 | 3.07 | −9.60 | −7.01 | |

| ◯ | R-MMU-983799 | REAC | Mitochondrial protein degradation | 24 | 1.54 | −9.29 | −6.76 | |

| ◯ | ◯ | GO:0021955 | GO BP | central nervous system neuron axonogenesis | 18 | 1.15 | −9.20 | −6.68 |

| ◯ | ◯ | R-MMU-6807505 | REAC | RNA polymerase II transcribes snRNA genes | 23 | 1.47 | −9.17 | −6.68 |

| Color | MCODE | GO | Description | Log10(P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red | MCODE_1 | mmu05214 | Glioma—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −7.8 |

| Red | MCODE_1 | WP1763 | Mechanisms associated with pluripotency | −7.7 |

| Red | MCODE_1 | mmu05200 | Pathways in cancer—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −7.2 |

| Blue | MCODE_2 | GO:0051123 | RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex assembly | −11.7 |

| Blue | MCODE_2 | GO:0070897 | transaction preinitiation complex assembly | −11.2 |

| Blue | MCODE_2 | GO:0060261 | positive regulation of transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II | −10.8 |

| Green | MCODE_3 | GO:0032543 | mitochondrial translation | −22.4 |

| Green | MCODE_3 | GO:0140053 | mitochondrial gene expression | −20.8 |

| Green | MCODE_3 | R-MMU-5419276 | Mitochondrial translation termination | −20.7 |

| Purple | MCODE_4 | GO:0042254 | ribosome biogenesis | −19.5 |

| Purple | MCODE_4 | GO:0022613 | ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis | −17.6 |

| Purple | MCODE_4 | R-MMU-8868773 | rRNA processing in the nucleus and cytosol | −17.5 |

| Orange | MCODE_5 | R-MMU-165159 | MTOR signaling | −8.7 |

| Orange | MCODE_5 | GO:1903432 | regulation of TORC1 signaling | −7.0 |

| Orange | MCODE_5 | R-MMU-166208 | mTORC1-mediated signaling | −6.9 |

| Yellow | MCODE_6 | mmu03083 | Polycomb repressive complex—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −9.9 |

| Yellow | MCODE_6 | R-MMU-8953750 | Transcriptional Regulation by E2F6 | −7.2 |

| Yellow | MCODE_6 | R-MMU-212436 | Generic Transcription Pathway | −3.7 |

| Brown | MCODE_7 | R-MMU-983169 | Class I MHC-mediated antigen processing & presentation | −5.7 |

| Brown | MCODE_7 | mmu04512 | ECM–receptor interaction—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −5.6 |

| Brown | MCODE_7 | mmu04120 | Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −4.9 |

| Pink | MCODE_8 | mmu04814 | Motor proteins—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −12.2 |

| Pink | MCODE_8 | R-MMU-2132295 | MHC class II antigen presentation | −10.5 |

| Pink | MCODE_8 | R-MMU-8856688 | Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | −10.4 |

| Gray | MCODE_9 | R-MMU-9013407 | RHOH GTPase cycle | −10.7 |

| Gray | MCODE_9 | R-MMU-9012999 | RHO GTPase cycle | −6.3 |

| Gray | MCODE_9 | R-MMU-194315 | Signaling by Rho GTPases | −5.6 |

| Teal | MCODE_10 | GO:0036503 | ERAD pathway | −8.7 |

| Teal | MCODE_10 | GO:0034976 | response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | −7.1 |

| Teal | MCODE_10 | GO:0010498 | proteasomal protein catabolic process | −5.8 |

| Lavender | MCODE_12 | R-MMU-9013424 | RHOV GTPase cycle | −8.5 |

| Lavender | MCODE_12 | R-MMU-9012999 | RHO GTPase cycle | −5.2 |

| Lavender | MCODE_12 | R-MMU-194315 | Signaling by Rho GTPases | −4.7 |

| Coral | MCODE_13 | R-MMU-9006936 | Signaling by TGFB family members | −6.9 |

| Coral | MCODE_13 | mmu04350 | TGF-beta signaling pathway—Mus musculus (house mouse) | −6.9 |

| Steel Blue | MCODE_14 | R-MMU-6794361 | Neurexins and neuroligins | −8.6 |

| Steel Blue | MCODE_14 | R-MMU-6794362 | Protein–protein interactions at synapses | −7.6 |

| Steel Blue | MCODE_14 | GO:0034329 | cell junction assembly | −5.5 |

| Pairwise Comparisons | and | Only | Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left cerebral cortex | > | Brain | △ | △ | ◯ | △ | △ |

| < | ◯ | △ | ◯ | ◯ | △ | ||

| Right cerebral cortex | > | ◯ | △ | ◯ | △ | △ | |

| < | ◯ | ◯ | △ | ◯ | × | ||

| Layer of hippocampus | > | ◯ | △ | ◯ | △ | △ | |

| < | ◯ | △ | ◯ | ◯ | × | ||

| Frontal cortex | > | △ | △ | ◯ | △ | △ | |

| < | ◯ | △ | △ | △ | × | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kobayashi, K.; Taguchi, Y.-h. Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons Regulate Sleep Deprivation and Recovery. Genes 2026, 17, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010051

Kobayashi K, Taguchi Y-h. Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons Regulate Sleep Deprivation and Recovery. Genes. 2026; 17(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleKobayashi, Kenta, and Y-h. Taguchi. 2026. "Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons Regulate Sleep Deprivation and Recovery" Genes 17, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010051

APA StyleKobayashi, K., & Taguchi, Y.-h. (2026). Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons Regulate Sleep Deprivation and Recovery. Genes, 17(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010051