The emergence of FDP marks a paradigm shift in modern forensic science. Where traditional DNA profiling has long been limited to identifying individuals through STR markers, FDP opens the possibility of predicting EVCs directly from genetic material, particularly in human remains [

45]. By bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype, FDP enables investigators to infer aspects of an unknown person’s physical appearance, ancestry, and even age from DNA found at a crime scene [

46]. This approach offers valuable investigative leads, especially in cases where conventional methods reach a dead end [

1].

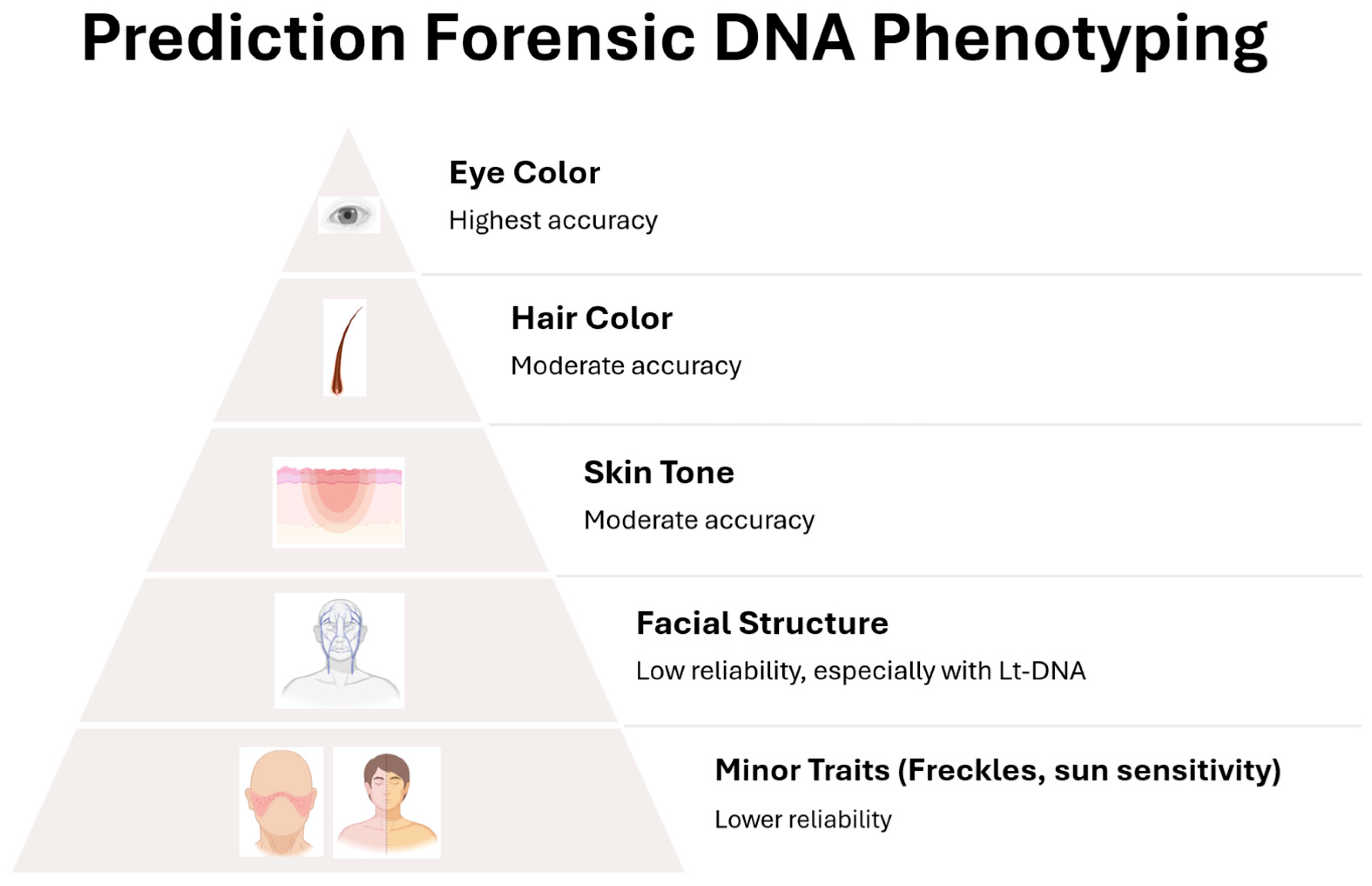

FDP currently focuses on a defined but gradually expanding set of traits, each with its own level of scientific maturity and predictive accuracy. Eye color, for instance, is among the most reliable phenotypic traits to be predicted from DNA, thanks to well-characterized variants in genes such as

HERC2 and

OCA2 [

47,

48]. In contrast, traits like skin pigmentation and hair color are more genetically complex, influenced by multiple genes and moderated by environmental factors. While red and black hair can be predicted with reasonable confidence, intermediate hair shades and skin tones remain more difficult to assess, particularly in admixed or non-European populations [

49,

50,

51].

Secondary traits such as freckling and sun sensitivity can further refine a DNA-based appearance profile, though they are typically used in conjunction with primary pigmentation traits [

52]. A more ambitious goal is the prediction of facial morphology, which remains one of the most challenging areas due to its highly polygenic nature and sensitivity to non-genetic influences like age, nutrition, and development. Although some genetic variants (e.g., in

PAX3 or

EDAR) have been associated with facial shape, practical applications in forensic casework are still in the early stages [

53].

In parallel, advancements in epigenetics have introduced the possibility of estimating chronological age from DNA, using methylation markers at specific CpG sites. Though age is not a fixed phenotype in the genetic sense, these DNA methylation-based “epigenetic clocks” offer promising tools for narrowing suspect or victim pools, particularly when traditional identifiers are absent [

54]. Moreover, biogeographical ancestry inference provides essential context for phenotype prediction, as genetic variant frequencies differ across populations [

55].

Tools like IrisPlex, HIrisPlex, and HIrisPlex-S panels, as well as the VISible Attributes through GEnomics (VISAGE) Enhanced Tool, have made FDP more accessible in forensic settings, allowing for targeted genotyping of key SNPs related to eye, hair, and skin color. Genotyping 24 genetic markers (SNPs and indels) enables rapid and reliable prediction of eye and hair color using the HIrisPlex system; the inclusion of 17 additional markers extends this capability to skin color prediction through the HIrisPlex-S system. While these panels show strong performance under ideal laboratory conditions, their predictive accuracy often diminishes in real-world scenarios involving degraded, mixed, or low-template DNA. As a result, integrating FDP into investigations requires not only scientific rigor but also careful consideration of its limitations and the probabilistic nature of the predictions it offers [

56,

57,

58,

59]. It is important to note that current forensic prediction panels (IrisPlex, HIrisPlex-S, VISAGE) primarily employ multinomial logistic regression for trait inference. These models are interpretable and validated for forensic use but differ fundamentally from ML approaches discussed later, which aim to capture complex genotype–phenotype relationships using non-linear, high-dimensional methods.

3.1. Forensic Eye Color Prediction from DNA: Insights from Genetic Markers

In forensic science, biological traces such as blood, saliva, semen, or epithelial cells recovered from crime scenes are primarily used for human identification through DNA profiling. However, recent advances have enabled the use of DNA to predict EVCs [

60].

Eye color prediction is based on the analysis of specific SNPs associated with pigmentation genes [

47]. These SNPs influence melanin synthesis and distribution in the iris, which, despite being covered by the transparent cornea, exhibits color variation due to both pigment concentration and structural light scattering in the stroma. The variation in iris color is primarily determined by the number and distribution of stromal melanocytes and the type of melanin, especially eumelanin, present [

61].

Eye color is a polygenic trait, with multiple genes contributing to its expression [

57]. Among these, the SNP rs12913832 in the

HERC2 gene has the most significant impact, particularly in European populations. Although located in an intronic region of

HERC2, this SNP regulates the expression of the

OCA2 gene, which encodes a protein essential for melanin transport. Individuals with the AA genotype at rs12913832 typically have blue eyes, GG genotype correlates with brown eyes, and AG heterozygotes often exhibit intermediate shades such as green or hazel [

62,

63].

Other genes, such as

SLC24A4,

SLC45A2,

TYR,

TYRP1,

ASIP or

IRF4, also contribute to eye color variation, especially for intermediate phenotypes. However, their predictive power is generally lower and may vary across populations. Polymorphisms in these genes, while informative, are often population-specific and less conserved than the

HERC2-OCA2 regulatory axis [

64,

65,

66].

To operate these genetic insights, the IrisPlex system was developed. This forensic tool uses a panel of six SNPs (

Table 1) to predict eye color using a multinomial logistic regression model. The system outputs probabilities for three eye color categories: blue, brown, and intermediate. A prediction is considered reliable when the highest probability exceeds a threshold of 0.7. For example, a prediction of 0.89 for blue, 0.08 for brown, and 0.03 for intermediate would be interpreted as blue eyes [

58].

Validation studies have demonstrated that IrisPlex achieves over 90% accuracy for blue and brown eyes in European populations. However, prediction accuracy for intermediate eye colors remains lower (around 73%), with sensitivity as low as 1.1%, reflecting the complex genetic architecture of these phenotypes [

58].

As detailed in

Section 2.3, LT-DNA introduces stochastic effects and allelic dropout that may compromise prediction accuracy. Future challenges in iris color prediction lie in integrating newly identified genetic markers to enhance predictive accuracy. A recent publication highlighted that whole-exome sequencing of 150 individuals has uncovered 27 previously unreported variants associated with eye color, offering promising new targets for prediction models. Notably, the SNP rs2253104 in the

ARFIP2 gene emerged as a key predictor, selected by multiple feature selection methods and contributing to the most accurate regression models. These findings suggest that expanding SNP panels with newly validated variants could significantly improve prediction outcomes, especially when working with degraded or limited DNA samples where maximizing the information from each locus is crucial. Validating and adapting these new markers for use in mini-amplicon assays could be a key step forward in applying iris prediction to challenging forensic samples [

47].

Additionally, high-sensitivity genotyping platforms, including MassARRAY (MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for multiplex SNP genotyping), NGS/MPS (parallel sequencing of multiple loci), and real-time PCR (using allele-specific probes or high-resolution melting analysis), have enhanced the precision and robustness of SNP detection [

51,

67]. Replicate testing and consensus genotyping further mitigate random amplification errors by allowing analysts to identify consistent results across multiple runs. Moreover, the integration of probabilistic models into prediction tools enables the communication of uncertainty levels, helping to avoid overinterpretation of marginal or ambiguous profiles. Enforcing strict quality control thresholds, such as minimum allele calling criteria and prediction probability cutoffs (e.g., >0.7), also ensures that only high-confidence phenotype predictions are reported. Nevertheless, certain limitations remain. Intermediate eye colors, for instance, continue to be difficult to predict accurately due to their polygenic inheritance patterns and relatively low heritability. Furthermore, variations in allele frequencies across populations can influence prediction outcomes, highlighting the necessity of validating predictive models in diverse genetic backgrounds to ensure their broader applicability and forensic reliability [

68].

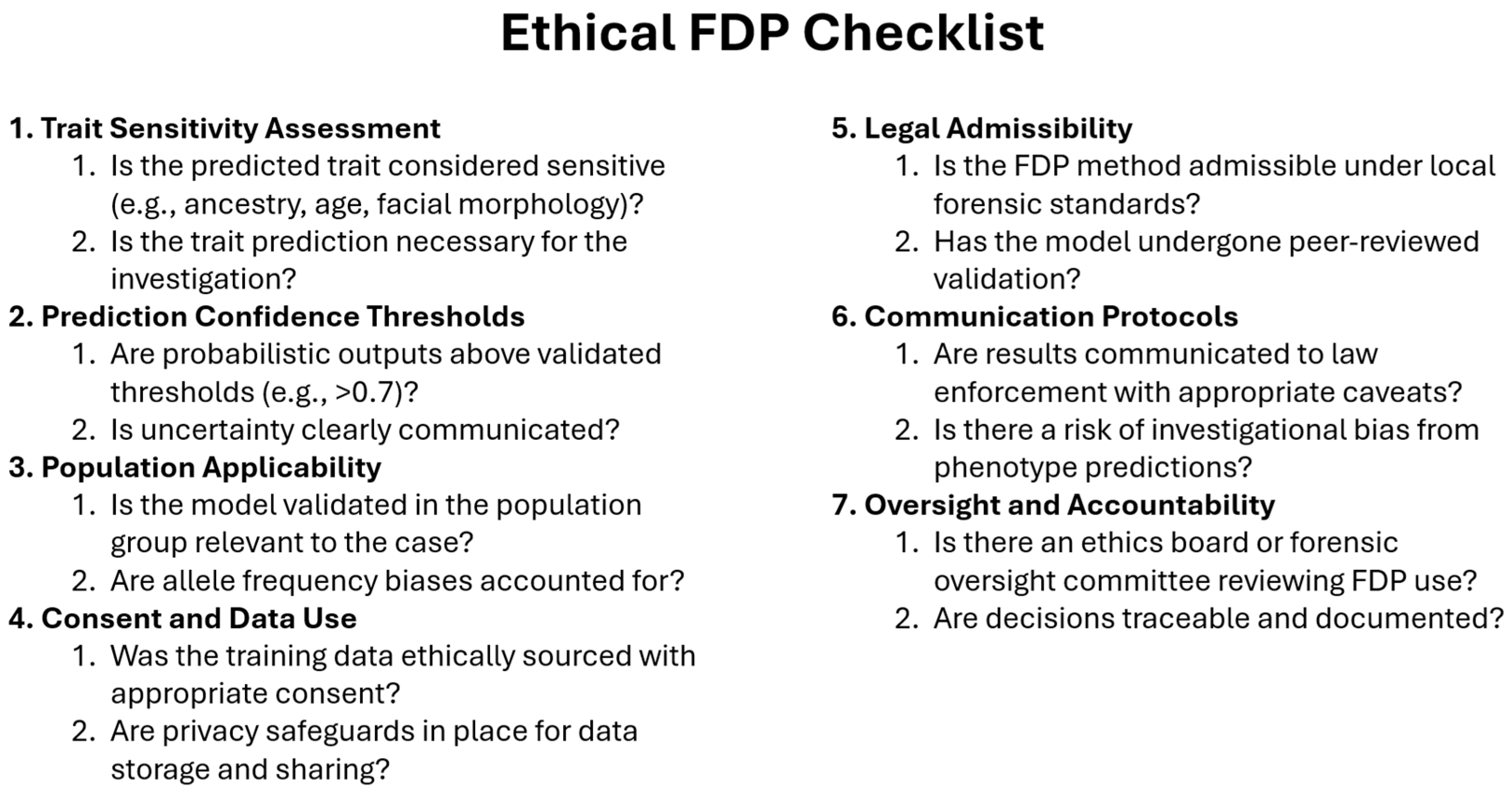

While eye color is generally considered a low-risk trait in terms of privacy, its use in FDP must adhere to ethical standards and legal frameworks. Misinterpretation of probabilistic predictions, especially in cases with low confidence or ambiguous results, can lead to investigational bias. Therefore, careful communication of FDP findings to law enforcement is crucial to avoid wrongful suspicion [

11,

69].

3.2. Hair Color Prediction from Biological Traces

When biological traces are collected, forensic experts apply extraction protocols designed to preserve DNA quality even from degraded or low template samples [

70]. Following DNA isolation and quantification, molecular techniques are used to identify SNPs associated with hair pigmentation [

71].

Specific DNA regions are involved in the production, distribution, and degradation of melanin, the pigment primarily responsible for hair, eye, and skin coloration [

56]. Hair color is determined by the type and quantity of melanin in the hair shaft: eumelanin (black/brown pigment) and pheomelanin (red/yellow pigment). The balance between these two types of melanin, regulated by a network of genes and genetic variants, gives rise to the wide spectrum of human hair colors, from black and brown to blond and red [

72].

Hair color is a complex trait shaped by the combined influence of many genes and their interactions, each contributing in different ways to the final pigmentation phenotype. Among these,

MC1R (Melanocortin 1 Receptor) plays a particularly prominent role. Variants in this gene are closely linked to red hair, as

MC1R controls the switch between the production of eumelanin (dark pigment) and pheomelanin (red/yellow pigment). When

MC1R function is disrupted by specific genetic variants, the balance shifts toward pheomelanin, leading to the characteristic red or auburn hair tones [

73,

74,

75].

Other genes also contribute significantly to hair color diversity.

HERC2 and

OCA2, which are more widely recognized for their role in determining eye color, also influence melanin synthesis in the hair, particularly affecting the variations observed in blond and brown shades [

48].

Genes such as

SLC24A4,

SLC45A2, and

TYR further support the pigmentation process by regulating melanosome function and the activity of tyrosinase, an enzyme critical for melanin biosynthesis. Variants in these genes are commonly associated with lighter hair tones [

76].

Lastly,

IRF4 has emerged as another important contributor. This gene influences pigmentation through its regulatory functions in melanocyte biology. Not only is it associated with lighter hair colors, but it is also implicated in age-related changes in pigmentation, such as the gradual transition to gray hair [

77].

The HIrisPlex system, developed as an extension of the earlier IrisPlex model for eye color prediction, integrates both eye and hair color SNPs into a single assay. As summarized in

Table 2, the system uses 24 SNPs across multiple pigmentation genes [

56].

The model outputs probability for each color, allowing forensic experts to assess the likely hair color of the DNA donor. A prediction is usually accepted when one color category exceeds a predefined probability threshold (e.g., >70%). For example, a sample yielding 0.82 probability for brown, 0.10 for black, 0.06 for blond, and 0.02 for red would result in a brown hair color prediction [

78].

The predictive accuracy of hair color varies by color category and population group. For example, red hair can be predicted with over 80–90% accuracy, primarily due to the strong effect of

MC1R variants [

79]. Blond and brown hair predictions are also relatively reliable (75–85%) but may show variation across different ethnic backgrounds. Black hair, being the most common worldwide, is typically predicted with high sensitivity but may have slightly lower specificity due to overlapping SNP effects [

80].

Prediction models have been validated in European populations, where hair color diversity is greatest. However, performance in non-European populations can differ due to allele frequency differences and additional contributing variants. Ongoing research continues to expand databases and improve prediction accuracy across ancestrally diverse groups [

81].

The utility of hair color prediction from biological traces hinges on the ability to generate accurate genotypes from compromised samples [

82].

In cases involving severely degraded DNA, MPS-based typing offers advantages by enabling parallel analysis of multiple short DNA fragments and improving coverage at key SNP sites [

67,

83,

84]. Still, probabilistic interpretation remains essential, particularly when prediction confidence falls below threshold values [

82].

Although hair color is a relatively non-sensitive trait in forensic terms, the use of predictive models still raises questions about genetic privacy, the potential for profiling, and public trust. Moreover, probabilistic results should be presented with appropriate caveats, particularly when based on partial or degraded DNA samples [

83].

3.3. Skin Pigmentation Prediction in Forensic Science from Biological Traces

The HIrisPlex-S model further incorporates skin color prediction and uses a total of 41 SNPs (

Table 3), enabling a broader EVC profile from a single DNA sample. This comprehensive approach improves the informative value of FDP in real-world investigations [

84].

While the SNP tables provide a comprehensive overview of markers used in FDP, performance varies significantly across panels and traits, especially under degraded-DNA conditions. The HIrisPlex-S system, which integrates eye, hair, and skin color prediction, has demonstrated robust performance in forensic contexts, including aged bone samples, ref. [

59] with successful recovery of pigmentation profiles in over 55% of cases [

9]. However, certain SNPs associated with skin tone (e.g., rs1426654 in

SLC24A5 and rs12913832 in

HERC2) show reduced amplification success in highly degraded samples, leading to underperformance in intermediate pigmentation categories. VISAGE panels, designed for massively parallel sequencing, offer improved sensitivity and multiplexing, enabling better SNP recovery from LT-DNA and degraded skeletal remains. Inter-laboratory validation studies [

59] confirm that VISAGE achieves higher reproducibility and lower dropout rates compared to HIrisPlex-S, particularly for skin color and ancestry inference. Nonetheless, both panels exhibit population-specific limitations: predictive accuracy is highest in European cohorts and declines in admixed populations, underscoring the need for inclusive reference datasets and ongoing calibration.

Skin pigmentation prediction from biological traces is an emerging and powerful facet of FDP, allowing forensic scientists to infer EVCs of unknown individuals when conventional identification techniques are unfeasible. Alongside eye and hair color, skin pigmentation provides essential descriptive features that can generate investigative leads from DNA alone. This is particularly relevant in cases involving unknown perpetrators, unidentified human remains, or degraded biological evidence [

85].

Biological traces recovered from crime scenes can contain sufficient nuclear DNA to permit genotyping, and in such cases, the typing of SNPs associated with pigmentation traits [

44]. Human skin color is primarily determined by the quantity and type of melanin produced by melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis. The density, distribution, and synthesis of melanin granules, regulated by a network of pigmentation genes, are key factors in determining skin tone [

86]. These processes are influenced by several genes that affect melanosome formation, melanocyte biology, and melanin biosynthesis pathways [

87]. Numerous genes have been associated with variations in skin pigmentation, many of which have been included in forensic prediction panels. Furthermore, skin color is a continuous trait influenced by both genetic and environmental factors (i.e., sun exposure, tanning behavior, and age can affect observed skin tone) [

88]. Its prediction from DNA is complex due to its polygenic nature, wide variation across populations, and the influence of evolutionary history. Despite this, robust predictive models have been developed, especially those designed to distinguish between broad pigmentation categories (light, intermediate, dark) across major global ancestries [

89]. This classification system simplifies the continuous nature of skin tone into practical categories for forensic investigation. The model utilizes logistic regression trained on a large reference dataset that includes individuals from diverse ancestral backgrounds [

90].

In validation studies, HIrisPlex-S demonstrated high accuracy, particularly in predicting light and dark pigmentation. Intermediate skin tones are more challenging due to greater phenotypic and genetic diversity and less clear boundaries between categories. The prediction accuracy is also influenced by the genetic background of the individual: for example, predictions are more reliable in populations of European or sub-Saharan African descent, and less so in admixed or South Asian populations [

81].

The prediction of skin color from LT-DNA is a promising yet complex frontier in forensic genetics. LT-DNA samples are inherently prone to degradation and contamination [

70]. These factors can compromise the integrity of genetic markers, particularly SNPs used in pigmentation prediction models such as HIrisPlex-S. Indeed, LT-DNA samples frequently result in incomplete genetic profiles, which limits the number of informative SNPs available for analysis. This can hinder the statistical confidence of phenotype predictions, especially in individuals with intermediate or admixed ancestry, where subtle genetic variations play a significant role in pigmentation. Advanced probabilistic models and imputation techniques are being developed to address these limitations, but their effectiveness remains contingent on the quality and completeness of the input DNA [

9].

Despite these challenges, LT-DNA-based skin color prediction remains a valuable tool in forensic investigations. When used responsibly, it can provide critical leads in otherwise unsolvable cases, offering a glimpse into the physical appearance of unknown individuals and narrowing suspect pools in a scientifically grounded manner.

3.4. Freckles and Sun Sensitivity Prediction in Forensic Science from Biological Traces

Among the suite of the prediction of EVCs from biological traces, freckles and sun sensitivity may seem minor at first glance, but they can contribute meaningfully to the construction of a biogeographic and phenotypic profile of an unknown individual [

91]. Freckles (ephelides) are small, pigmented macules that typically appear on sun-exposed areas of fair skin. Sun sensitivity refers to a person’s susceptibility to burning rather than tanning upon UV exposure, typically resulting from lower eumelanin levels and higher pheomelanin content [

86]. These traits, rooted in pigmentation biology, are closely associated with genes involved in melanin synthesis and regulation, particularly the

MC1R gene, located on chromosome 16 [

92]. Several common

MC1R variants (e.g., R151C, R160W, D294H) are collectively referred to as “R alleles” and are associated with the red hair color (RHC) phenotype, but also contribute independently to freckling and UV sensitivity, even in individuals without red hair [

93]. Other genes, such as

ASIP,

TYR, and

IRF4, may modulate freckling and pigmentation patterns, although their effects are smaller and often population-specific [

94].

With appropriate genetic analysis, forensic scientists can derive probabilistic predictions about whether an individual is likely to have freckled skin and/or increased sensitivity to sunlight. The relative SNPs are included in comprehensive forensic phenotyping tools such as HIrisPlex-S [

85]. These models use multinomial logistic regression or ML classifiers trained on large, multi-ethnic datasets [

51,

95]. For freckles, individuals are categorized as likely or unlikely to have them based on the presence of specific MC1R variants and other associated SNPs [

3,

96,

97,

98,

99]. For sun sensitivity, prediction involves assessing genetic profiles associated with reduced melanin production and increased burn tendency (high likelihood of sunburn with minimal tanning, moderate sensitivity, low sensitivity/likely to tan) [

100].

Prediction accuracy for freckles and sun sensitivity is generally good when the relevant SNPs are reliably genotyped, and the individual belongs to a well-represented population in the model’s training data (typically of European ancestry) [

51]. For instance, freckle prediction can reach accuracies above 75–80%, particularly when individuals carry two or more non-functional MC1R alleles. Sun sensitivity prediction is somewhat more variable due to the continuous nature of the phenotype and its interaction with environmental factors (e.g., lifetime sun exposure, behavior, geography) [

101].

However, there are several limitations: -polygenic complexity: many small-effect genes and gene-environment interactions contribute to these traits; -environmental influence: freckling can be influenced by UV exposure history, making it a dynamic, rather than strictly genetically determined, trait; -population bias: predictive models perform best in individuals of European ancestry, where pigmentation variation is highest and best studied; accuracy drops in admixed or underrepresented populations; -LT-DNA [

100].

3.5. Facial Morphology Prediction in Forensic Science from Biological Traces

In the field of FDP, the prediction of facial morphology, the shape and structure of the human face, represents a frontier with considerable scientific promise and complex challenges [

102]. While traits like eye, hair, and skin color have reached relatively high predictive reliability, facial morphology prediction is more intricate due to the polygenic and multifactorial nature of facial features. However, recent advances in genomics, 3D facial imaging, and ML models are progressively transforming facial prediction from a speculative vision into an emerging forensic tool. The ability to reconstruct aspects of a person’s facial structure from biological traces such as blood, saliva, or touch DNA could significantly support investigations, particularly when no biometric or documentary information is available [

102,

103].

Facial morphology is a highly heritable trait governed by the interaction of hundreds of genes and regulatory elements. GWAS have identified dozens of loci associated with specific facial traits, including: facial width and height, nasal bridge length and tip projection, lip thickness, chin prominence, brow ridge shape, mandibular and maxillary dimensions [

6,

104].

Key genes such as

PAX3,

EDAR,

DCHS2,

RUNX2, and

PRDM16 have been linked to facial development, often through their role in craniofacial growth, tissue differentiation, and skeletal patterning. Variants in these genes influence the position and projection of facial landmarks that define individual appearance. Notably, the expression of these traits is further modulated by age, sex, ancestry, and environmental influences (e.g., nutrition, trauma), which makes prediction from DNA alone inherently probabilistic [

105,

106].

In addition to genotyping, the ancestry and sex of the donor are determined, as both play pivotal roles in shaping facial morphology. Ancestry informs baseline structural patterns common in different populations (e.g., nasal breadth, cheekbone prominence), while sex influences sexually dimorphic traits such as jaw angle and brow thickness [

107].

To transform genetic data into facial predictions, researchers apply ML techniques trained on large databases of paired genotype and 3D facial imaging data. These datasets often consist of thousands of individuals with detailed facial scans and genome-wide SNP data. Key modeling approaches include partial least squares regression (PLSR) to link SNPs to principal components of facial variation; convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to analyze facial geometry from genetic and demographic inputs; deep generative models (e.g., variational autoencoders or GANs) to create realistic 3D face renderings from DNA data [

108].

Recent examples include the FaceBase project, VisiGen, and research from the Penn State Forensic Anthropology Lab, which has shown that genetic data can explain 10–20% of the variance in certain facial traits, modest but meaningful progress toward practical forensic use [

109,

110]. Despite promising advances, current models explain only a modest proportion of facial trait variance, typically between 10–20%, with substantial limitations in predicting features influenced by environmental and developmental factors. Traits such as facial asymmetry, age-related changes, and expression dynamics remain poorly captured by genotype-based models. This modest predictive power underscores that current models are research-grade and unsuitable for operational forensic deployment.

The predictive power of facial trait modeling is strongest when combined with known ancestry, sex, and age estimates, particularly in young adults, whose facial structures are relatively stable. Nonetheless, these models often lack precision at the individual level and are more effective at generating composite depictions or narrowing demographic search pools than at identifying exact facial characteristics. Reproducibility remains a major challenge in facial morphology prediction. Variability in imaging techniques, SNP panels, and population structure can lead to inconsistent results across studies. Moreover, the lack of standardized validation protocols and limited availability of forensic-grade datasets restrict the generalizability of current models. According to recent publications, the highest predictability is observed for traits such as nose width, facial width, intercanthal distance (the distance between the eyes), and lip thickness. Moderate predictability applies to features like brow ridge prominence, chin shape, and nasal tip projection. In contrast, traits such as facial asymmetry, expression-related features, and age-related morphological changes exhibit low predictability [

46,

111].

In forensic contexts, these predictions are used as investigative leads rather than as confirmatory evidence. Reproducibility remains limited due to variability in imaging protocols, SNP panels, and population structure. Most data sets are European-biased, reducing generalizability and increasing misclassification risk in admixed populations. Future efforts should focus on expanding training datasets to include diverse populations, integrating multi-omics data to capture non-genetic influences, and establishing standardized pipelines for model development and validation to enhance reproducibility and forensic reliability. For example, in cold cases, a predicted facial image may be released to the public to generate tips. In mass disaster scenarios, facial predictions can assist in identifying unknown victims when traditional methods, such as fingerprinting or dental records, are unavailable. Similarly, in cases involving unidentified remains, predicted facial features can complement skeletal reconstructions and ancestry estimations, enhancing the overall identification process.

Facial prediction from LT-DNA represents a cutting-edge intersection of forensic genetics and computational modeling. Facial predictions derived from LT-DNA are probabilistic rather than definitive and are best used to generate investigative leads rather than serve as conclusive evidence [

3,

102]. Indeed, despite promising advances, current models explain only 10–20% of variance in facial traits, which is insufficient for individual-level reconstruction. These outputs remain research-grade and are not forensically deployable. Reproducibility is constrained by differences in imaging protocols, SNP panels, and population structure. Beyond technical limitations, predicting facial morphology raises significant ethical concerns. Unlike eye, hair, and skin color, facial features are closely linked to ancestry and identity, making them particularly sensitive. Generated facial composites risk being misinterpreted as accurate likenesses, potentially leading to investigational bias or discrimination. These challenges underscore the need for transparent communication of uncertainty, strict governance, and clear disclaimers when using such predictions as investigative leads rather than confirmatory evidence.

3.6. Age Prediction in Forensic Science Based on Biological Traces

Estimating chronological age from biological traces has become a valuable forensic tool, particularly when conventional identifiers are unavailable [

112]. Unlike skeletal assessments, molecular approaches rely on biomarkers that change predictably over time [

113]. Among these, DNA methylation at specific CpG sites is the most reliable indicator of age, outperforming earlier methods based on telomere length or mtDNA mutations, which showed high variability and limited forensic utility [

114,

115,

116].

Epigenetic clocks exploit methylation changes at selected loci to predict age with high accuracy. Forensic models prioritize simplicity and robustness for degraded or LT-DNA. A widely used approach by Bekaert et al. employs four CpG sites in genes such as

ELOVL2,

FHL2,

KLF14, and

TRIM59, achieving mean absolute deviations of about 3–4 years in blood samples.

ELOVL2 is particularly informative due to its consistent methylation increase across tissues, including blood, saliva, and buccal cells [

117]. The VISAGE Consortium has further advanced this field by creating multiplex assays compatible with NGS, enabling sensitive and robust age estimation from trace DNA.

ELOVL2, in particular, has emerged as a key biomarker due to its consistent methylation increase with age across multiple tissue types, including blood, saliva, and buccal cells [

118].

One of the strengths of DNA methylation-based age prediction is its applicability across various forensic sample types [

119]. Blood and saliva are most commonly used due to their higher DNA yield and stable methylation profiles. Semen requires tissue-specific models, as methylation patterns vary significantly between tissues. Touch DNA, derived from epithelial cells, presents greater challenges due to low DNA quantities, but ongoing research is improving its feasibility. Even skeletal remains can be analyzed for methylation-based age estimation, offering valuable insights in cold cases or mass grave investigations [

112,

120].

In forensic casework, age prediction serves multiple roles. It can assist in suspect profiling when no known individual is linked to the biological evidence, providing an estimated age range to guide investigations. In victim identification, especially in cases involving unidentified remains, age estimates help correlate findings with missing persons databases. Additionally, age prediction is sometimes used in legal and immigration contexts to determine whether individuals are minors, although this application remains ethically and legally contentious [

121,

122].

Technological platforms for methylation analysis include pyrosequencing, quantitative PCR, and NGS. Pyrosequencing remains popular for targeted assays because of its cost-effectiveness and compatibility with forensic workflows, while NGS offers higher sensitivity and multiplexing for degraded samples. Recent VISAGE Consortium developments integrate methylation-based age estimation into multiplex panels, enabling simultaneous prediction of age and other traits from trace DNA [

123,

124].

Despite these advances, LT-DNA poses challenges such as allelic dropout and incomplete methylation profiles, which can reduce accuracy [

125]. Optimized assays using short amplicons, replicate testing, and probabilistic models help mitigate these issues [

126]. When combined with strict quality control and robust statistical frameworks, methylation-based age prediction provides actionable investigative leads, even from compromised samples [

127].

3.7. Ancestry Prediction in Forensic Science from Biological Traces

Ancestry prediction from biological traces has become a powerful tool in forensic science, offering critical insights into the biogeographical origins of unknown individuals when traditional identification methods are unavailable [

128]. This approach is particularly valuable in criminal investigations, mass disasters, and the identification of unidentified remains, where DNA evidence may be the only clue. Unlike cultural or self-reported ethnicity, forensic ancestry inference relies on genetic markers that reflect population-level differences shaped by evolutionary history, migration, and genetic drift. These markers, primarily SNPs, are distributed across the genome and exhibit frequency patterns that vary among continental and subcontinental populations [

129].

The foundation of ancestry prediction lies in the analysis of ancestry-informative markers (AIMs), SNPs selected for their high allele frequency differences between populations. Panels such as the SNPforID 34-plex or others, such as the Precision ID Ancestry Panel, include hundreds of AIMs optimized for forensic use. These panels can distinguish major continental ancestries (e.g., African, European, East Asian, Native American, South Asian) and, in some cases, provide finer resolution within regions [

130,

131]. The VISAGE Consortium has developed advanced multiplex assays compatible with MPS, enabling ancestry inference from degraded or LT-DNA samples commonly encountered in forensic contexts [

59,

132].

Despite the promise of ancestry prediction, several challenges must be addressed, particularly when working with LT-DNA. However, recent advances in sequencing sensitivity and bioinformatic tools have improved the robustness of ancestry inference from trace samples. Probabilistic models and ML algorithms can now integrate partial genotypes and assign ancestry with high confidence, even from compromised DNA [

90,

133].

In forensic casework, ancestry prediction serves multiple purposes. It can help narrow suspect pools by providing investigators with information about the likely population background of an unknown individual. In missing persons cases, ancestry estimates can guide comparisons with databases and assist in facial reconstruction efforts. In mass disaster scenarios, ancestry inference can support victim identification when other biological or contextual information is lacking. Importantly, ancestry prediction is not intended to identify individuals directly but to provide investigative leads that complement other forensic evidence [

134].

The accuracy of ancestry prediction depends on several factors, including the number and informativeness of SNPs used, the diversity of reference populations, and the complexity of individual genetic backgrounds. Admixed individuals, those with ancestry from multiple populations, pose particular challenges, as their genetic profiles may not align neatly with reference categories. To address this, modern forensic tools incorporate admixture analysis and ancestry deconvolution, estimating proportional ancestry contributions from different populations. These methods enhance the interpretability of results and reduce the risk of misclassification [

135].

As forensic genomics continues to evolve, ancestry prediction from biological traces, especially LT-DNA, will play an increasingly important role in investigative workflows. With ongoing improvements in marker panels, sequencing technologies, and computational methods, the ability to infer ancestry from even the most challenging samples is becoming more accurate and accessible, offering valuable insights in the pursuit of justice.