Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with LCMV-G in Gene Transfer to Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

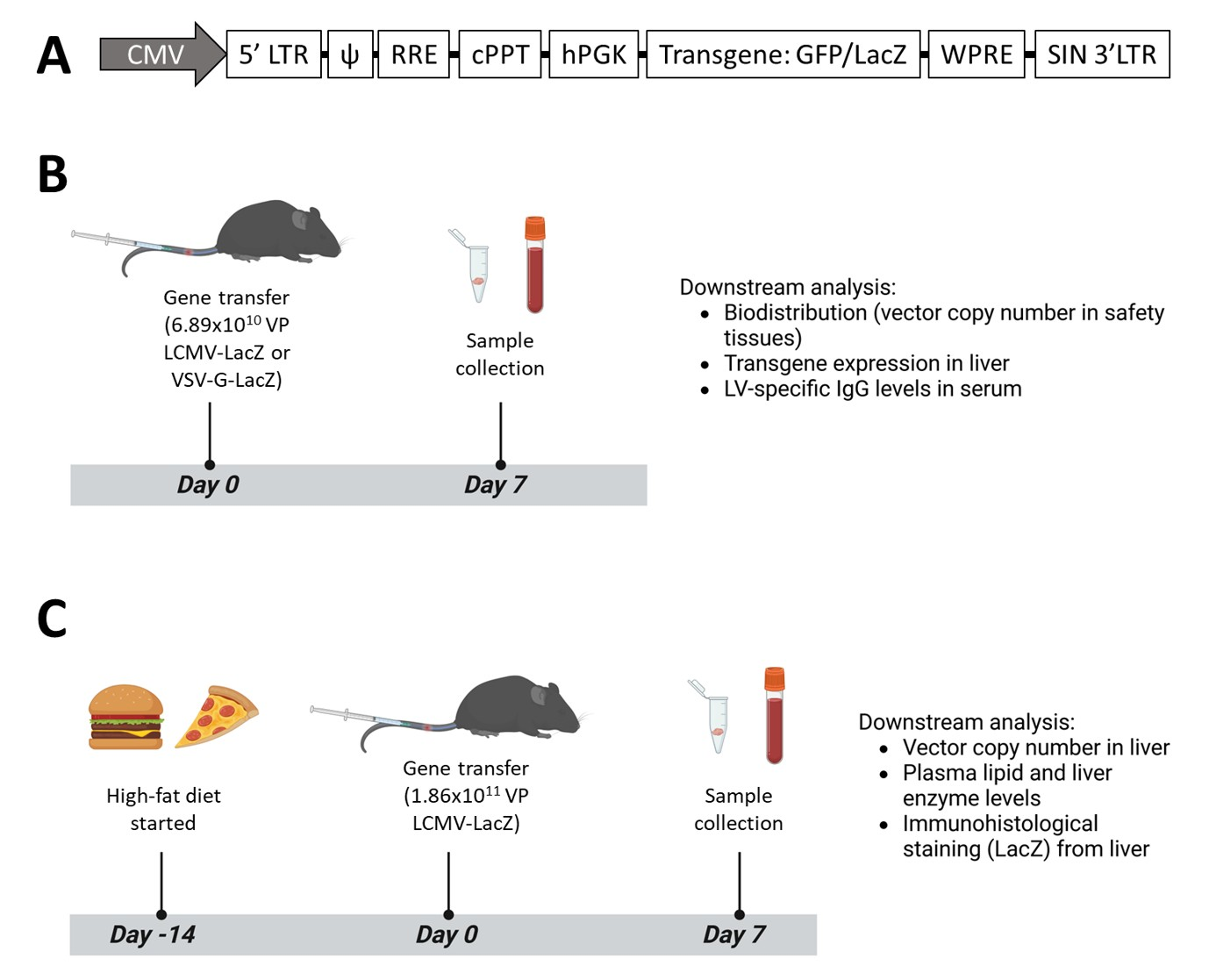

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lentivirus Vector Production

2.2. In Vitro Testing of LCMV-Pseudotyped LVs

2.3. In Vivo Gene Transfer

2.4. Histological Staining and Analysis of Mouse Tissue Samples

2.5. Analysis of Mouse Serum and Plasma Samples

2.6. Droplet Digital PCR Analysis of Vector Copy Number and LV Biodistribution

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

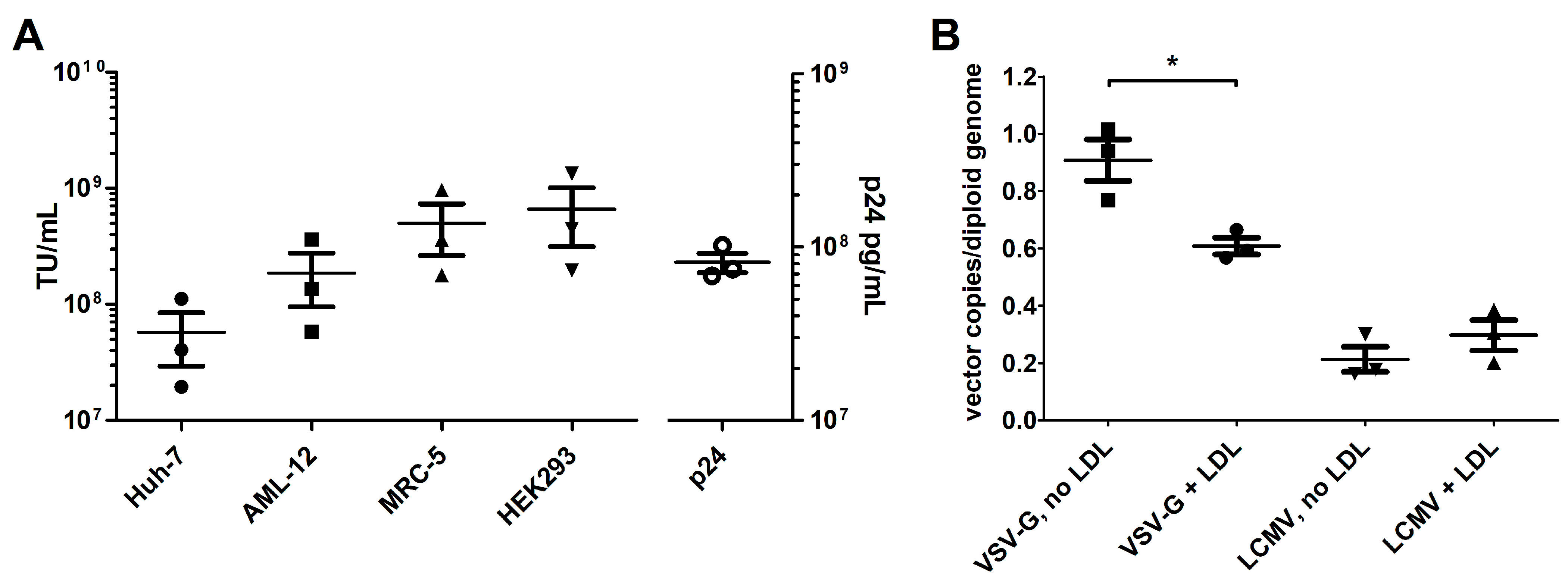

3.1. In Vitro Characterization of LCMV-Pseudotyped LVs

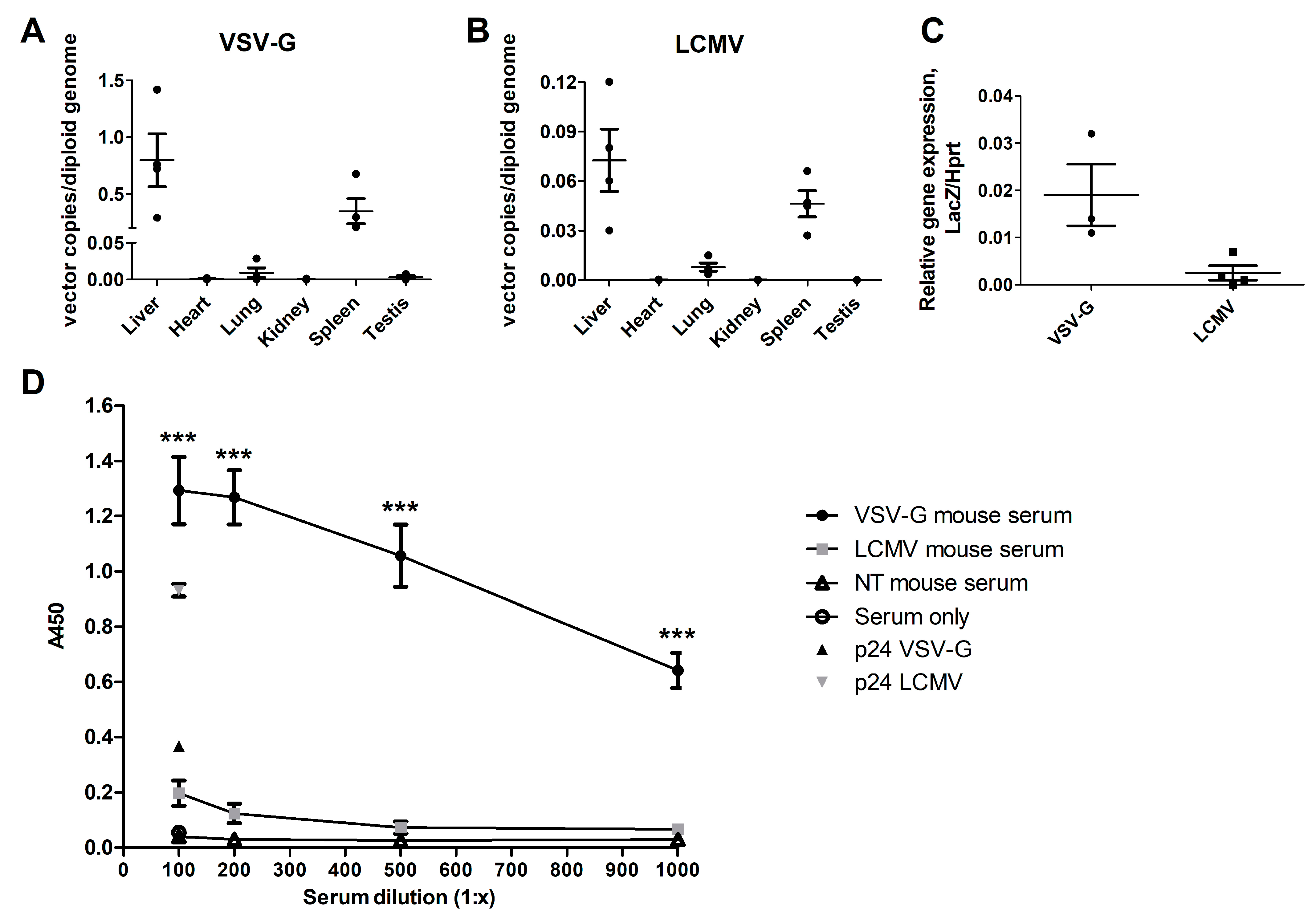

3.2. LCMV-LV-Mediated Gene Transfer to Ldlr-KO Mouse Liver Is Lower than with VSV-G-LVs

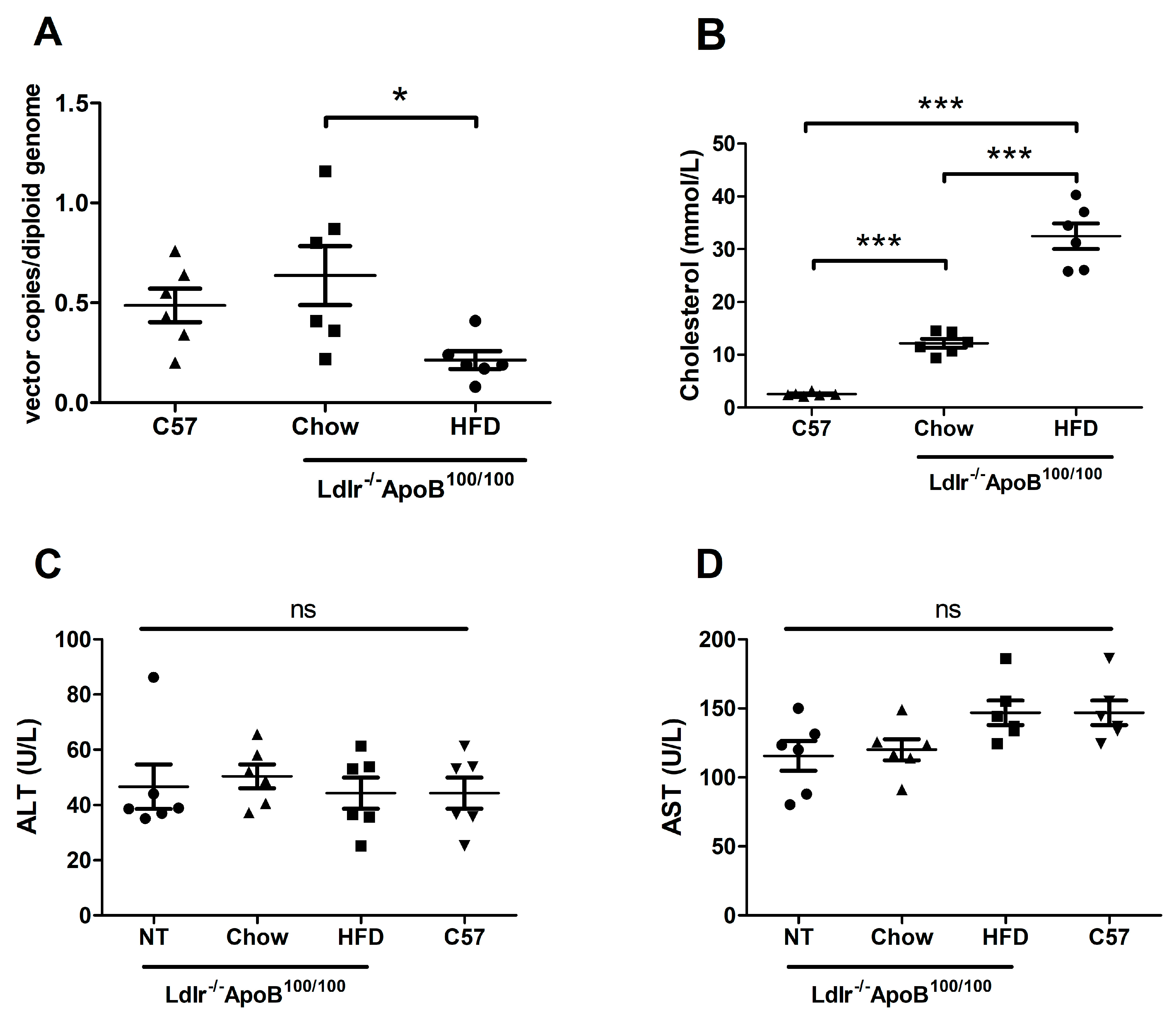

3.3. HFD Reduces LCMV-LV-Mediated Gene Transfer to Ldlr-KO Mouse Liver

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LV | Lentiviral vector |

| VSV-G | Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein |

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| LCMV | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| BaEV | Baboon retroviral envelope glycoprotein |

| SSP | Stable signal peptide |

| GP1 | Glycoprotein 1 |

| GP2 | Glycoprotein 2 |

| Ldlr-KO | Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| VP | Vector particle |

| ddPCR | Droplet digital PCR |

| i.v. | Intravenous |

| VCN | Vector copy number |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| TU/mL | LV infectious titer, transducing units per mL |

| LRP1 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 |

References

- Sakuma, T.; Barry, M.A.; Ikeda, Y. Lentiviral vectors: Basic to translational. Biochem J. 2012, 443, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dull, T.; Zufferey, R.; Kelly, M.; Mandel, R.J.; Nguyen, M.; Trono, D.; Naldini, L. A Third-Generation Lentivirus Vector with a Conditional Packaging System. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8463–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, H.; Blomer, U.; Takahashi, M.; Gage, F.H.; Verma, I.M. Development of a Self-Inactivating Lentivirus Vector. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 8150–8157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, K.A.; Landau, N.R.; Littman, D.R. Construction and use of a human immunodeficiency virus vector for analysis of virus infectivity. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 5270–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, R.; Nagy, D.; Mandel, R.J.; Naldini, L.; Trono, D. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, J.; Belot, L.; Raux, H.; Legrand, P.; Gaudin, Y.; Albertini, A.A. Structural basis for the recognition of LDL-receptor family members by VSV glycoprotein. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelshtein, D.; Werman, A.; Novick, D.; Barak, S.; Rubinstein, M. LDL receptor and its family members serve as the cellular receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7306–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard-Gagnepain, A.; Amirache, F.; Costa, C.; Lévy, C.; Frecha, C.; Fusil, F.; Nègre, D.; Lavillette, D.; Cosset, F.L.; Verhoeyen, E. Baboon envelope pseudotyped LVs outperform VSV-G-LVs for gene transfer into early-cytokine-stimulated and resting HSCs. Blood 2014, 124, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernadin, O.; Amirache, F.; Girard-Gagnepain, A.; Moirangthem, R.D.; Lévy, C.; Ma, K.; Costa, C.; Nègre, D.; Reimann, C.; Fenard, D.; et al. Baboon envelope LVs efficiently transduced human adult, fetal, and progenitor T cells and corrected SCID-X1 T-cell deficiency. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, K.; Vigant, F.; Van Handel, B.; Pernet, O.; Chikere, K.; Hong, P.; Sherman, S.P.; Patterson, M.; An, D.S.; Lowry, W.E.; et al. Nipah Virus Envelope-Pseudotyped Lentiviruses Efficiently Target ephrinB2-Positive Stem Cell Populations In Vitro and Bypass the Liver Sink When Administered In Vivo. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2094–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajawat, Y.S.; Humbert, O.; Cook, S.M.; Radtke, S.; Pande, D.; Enstrom, M.; Wohlfahrt, M.E.; Kiem, H.P. In Vivo Gene Therapy for Canine SCID-X1 Using Cocal-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021, 32, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Ikawa, Y.; Takenaka, M.; Sakai, Y.; Fujiki, T.; Kuroda, R.; Chappell, M.; Ghiaccio, V.; Rivella, S.; Wada, T. Protocol for a high titer of BaEV-Rless pseudotyped lentiviral vector: Focus on syncytium formation and detachment. J. Virol. Methods 2023, 314, 114689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquato, A.; Cendron, L.; Kunz, S. Cleavage of the glycoprotein of arenaviruses. In Activation of Viruses by Host Proteases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319754741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylla, D.E.; Xie, L.; Michele, D.E.; Kunz, S.; McCray, P.B. Altering α-dystroglycan receptor affinity of LCMV pseudotyped lentivirus yields unique cell and tissue tropism. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2011, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimojima, M.; Kawaoka, Y. Cell surface molecules involved in infection mediated by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012, 74, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, W.R.; Westphal, M.; Ostertag, W.; von Laer, D. Oncoretrovirus and Lentivirus Vectors Pseudotyped with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Glycoprotein: Generation, Concentration, and Broad Host Range. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, B.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P. Pseudotyping Lentiviral Vectors with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Glycoproteins for Transduction of Dendritic Cells and In Vivo Immunization. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods 2014, 25, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, F. Correction of Bleeding Diathesis Without Liver Toxicity Using Arenaviral-Pseudotyped HIV-1-Based Vectors in Hemophilia A Mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 2003, 14, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véniant, M.M.; Zlot, C.H.; Walzem, R.L.; Pierotti, V.; Driscoll, R.; Dichek, D.; Herz, J.; Young, S.G. Lipoprotein clearance mechanisms in LDL receptor-deficient “apo-B48- only” and “apo-B100-only” mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S.E.; Kivelä, A.M.; Huusko, J.; Dijkstra, M.H.; Gurzeler, E.; Mäkinen, P.I.; Leppänen, P.; Olkkonen, V.M.; Eriksson, U.; Jauhiainen, M.; et al. The effects of VEGF-A on atherosclerosis, lipoprotein profile, and lipoprotein lipase in hyperlipidaemic mouse models. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 99, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivelä, A.M.; Huusko, J.; Gurzeler, E.; Laine, A.; Dijkstra, M.H.; Dragneva, G.; Andersen, C.B.F.; Moestrup, S.K.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. High Plasma Lipid Levels Reduce Efficacy of Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Hao, Y.; Tang, W.; Diering, G.H.; Zou, F.; Kafri, T. Analysis of Hepatic Lentiviral Vector Transduction: Implications for Preclinical Studies and Clinical Gene Therapy Protocols. Viruses 2025, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follenzi, A.; Naldini, L. Generation of HIV-1 derived lentiviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2002, 346, 454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, H. How to calculate sample size in animal studies? Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 1, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xu, W.; Luo, S.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Q. Improving the production of BaEV lentivirus by comprehensive optimization. J. Virol. Methods 2025, 333, 115106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio-Kokko, H.; Laakkonen, J.; Rizzoli, A.; Tagliapietra, V.; Cattadori, I.; Perkins, S.E.; Hudson, P.J.; Cristofolini, A.; Versini, W.; Vapalahti, O.; et al. Hantavirus and arenavirus antibody prevalence in rodents and humans in Trentino, Northern Italy. Epidemiol. Infect. 2006, 134, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Oreski, T.; Korva, M.; Kolaric, B.; Stevanovic, V.; Zidovec-Lepej, S.; Tabain, I.; Jelicic, P.; Miklausic-Pavic, B.; Savic, V.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection in Continental Croatian Regions. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, J.; Hamann, U.; Rogne, S.; Myklebost, O.; Gausepohl, H.; Stanley, K.K. Surface location and high affinity for calcium of a 500-kd liver membrane protein closely related to the LDL-receptor suggest a physiological role as lipoprotein receptor. EMBO J. 1988, 7, 4119–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillis, A.P.; Van Duyn, L.B.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E.; Strickland, D.K. LDL receptor-related protein 1: Unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 887–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Gunther, R.; Duan, W.; Wendell, S.; Kaemmerer, W.; Kafri, T.; Verma, I.M.; Whitley, C.B. Biodistribution and Toxicity Studies of VSVG-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector after Intravenous Administration in Mice with the Observation of in Vivo Transduction of Bone Marrow. Mol. Ther. 2002, 6, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annoni, A.; Battaglia, M.; Follenzi, A.; Lombardo, A.; Sergi-Sergi, L.; Naldini, L.; Roncarolo, M.G. The immune response to lentiviral-delivered transgene is modulated in vivo by transgene-expressing antigen-presenting cells but not by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Blood 2007, 110, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unemo, M.; Cole, M.; Lewis, D.; Ndowa, F.; Van Der Pol, B.; Wi, T. Laboratory and Point-of-Care Diagnostic Testing for Sexually Transmitted Infections, Including HIV; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-92-4-007709-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley, J.L.; de Jong, Y.P.; Terhorst, C.; Herzog, R.W. Immune Responses to Viral Gene Therapy Vectors. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschli, B.; Zellweger, R.M.; Wepf, A.; Lang, K.S.; Quirin, K.; Weber, J.; Zinkernagel, R.M.; Hengartner, H. Early Antibodies Specific for the Neutralizing Epitope on the Receptor Binding Subunit of the Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Glycoprotein Fail To Neutralize the Virus. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11650–11657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recher, M.; Lang, K.S.; Hunziker, L.; Freigang, S.; Eschli, B.; Harris, N.L.; Navarini, A.; Senn, B.M.; Fink, K.; Lötscher, M.; et al. Deliberate removal of T cell help improves virus-neutralizing antibody production. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczmiel, U.; Kräutler, N.J.; Pedrioli, A.; Bartsch, I.; Agnellini, P.; Bedenikovic, G.; Harker, J.; Richter, K.; Oxenius, A. Sustained T follicular helper cell response is essential for control of chronic viral infection. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, 8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, T.; Schweier, O.; Bruns, M.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Waisman, A.; Pircher, H. Nucleoprotein-specific nonneutralizing antibodies speed up LCMV elimination independently of complement and FcγR. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 2338–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, A.R.; Nansen, A.; Andersen, C.; Johansen, J.; Marker, O.; Christensen, J.P. Cooperation of B cells and T cells is required for survival of mice infected with vesicular stomatitis virus. Int. Immunol. 1997, 9, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.D.; Sitia, G.; Annoni, A.; Hauben, E.; Sergi, L.S.; Zingale, A.; Roncarolo, M.G.; Guidotti, L.G.; Naldini, L. In vivo administration of lentiviral vectors triggers a type I interferon response that restricts hepatocyte gene transfer and promotes vector clearance. Blood 2007, 109, 2797–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, G.S.; Reardon, C.A. Animal Models of Atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.D.; Venneri, M.A.; Zingale, A.; Sergi, L.S.; Naldini, L. Endogenous microRNA regulation suppresses transgene expression in hematopoietic lineages and enables stable gene transfer. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, M.; Annoni, A.; Moalli, F.; Liu, T.; Cesana, D.; Calabria, A.; Bartolaccini, S.; Biffi, M.; Russo, F.; Visigalli, I.; et al. Phagocytosis-shielded lentiviral vectors improve liver gene therapy in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Function | |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudotyping constructs | VSV-G | Control envelope |

| LCMV | Pseudotype tested for characterization | |

| Transgene constructs | hPGK-EGFP | Reporter for in vitro testing |

| hPGK-LacZ | Reporter for in vivo gene transfer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nousiainen, A.; Ruotsalainen, A.-K.; Hokkanen, K.; Laidinen, S.; Tawfek, A.; Schenkwein, D.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with LCMV-G in Gene Transfer to Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 Mice. Genes 2026, 17, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010060

Nousiainen A, Ruotsalainen A-K, Hokkanen K, Laidinen S, Tawfek A, Schenkwein D, Ylä-Herttuala S. Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with LCMV-G in Gene Transfer to Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 Mice. Genes. 2026; 17(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleNousiainen, Alisa, Anna-Kaisa Ruotsalainen, Krista Hokkanen, Svetlana Laidinen, Ahmed Tawfek, Diana Schenkwein, and Seppo Ylä-Herttuala. 2026. "Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with LCMV-G in Gene Transfer to Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 Mice" Genes 17, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010060

APA StyleNousiainen, A., Ruotsalainen, A.-K., Hokkanen, K., Laidinen, S., Tawfek, A., Schenkwein, D., & Ylä-Herttuala, S. (2026). Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with LCMV-G in Gene Transfer to Ldlr−/−ApoB100/100 Mice. Genes, 17(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010060