Expanded Carrier Screening: Current Evidence and Future Directions in the Era of Population Genomics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gene Selection Criteria in Expanded Carrier Screening

3. Interpretation Challenges and Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS)

4. Inclusion of Lethal Genes in ECS Panels: Ethical and Clinical Considerations

- Identify more couples at risk for conceptions that fail before clinical pregnancy is established.

- Explain otherwise “idiopathic” infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss.

- Enable targeted reproductive interventions such as preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) to prevent repeated failed cycles or miscarriages.

- Yet, the inclusion of such genes also presents significant challenges:

- Interpretation difficulty, due to limited functional evidence, incomplete penetrance, or uncertain pathogenicity.

- Communication challenges, as couples may struggle to interpret risks related to embryonic outcomes that occur before pregnancy detection.

- Ethical concerns, including potential anxiety, overuse of assisted reproductive technologies, and decisions based on incomplete or population-specific evidence.

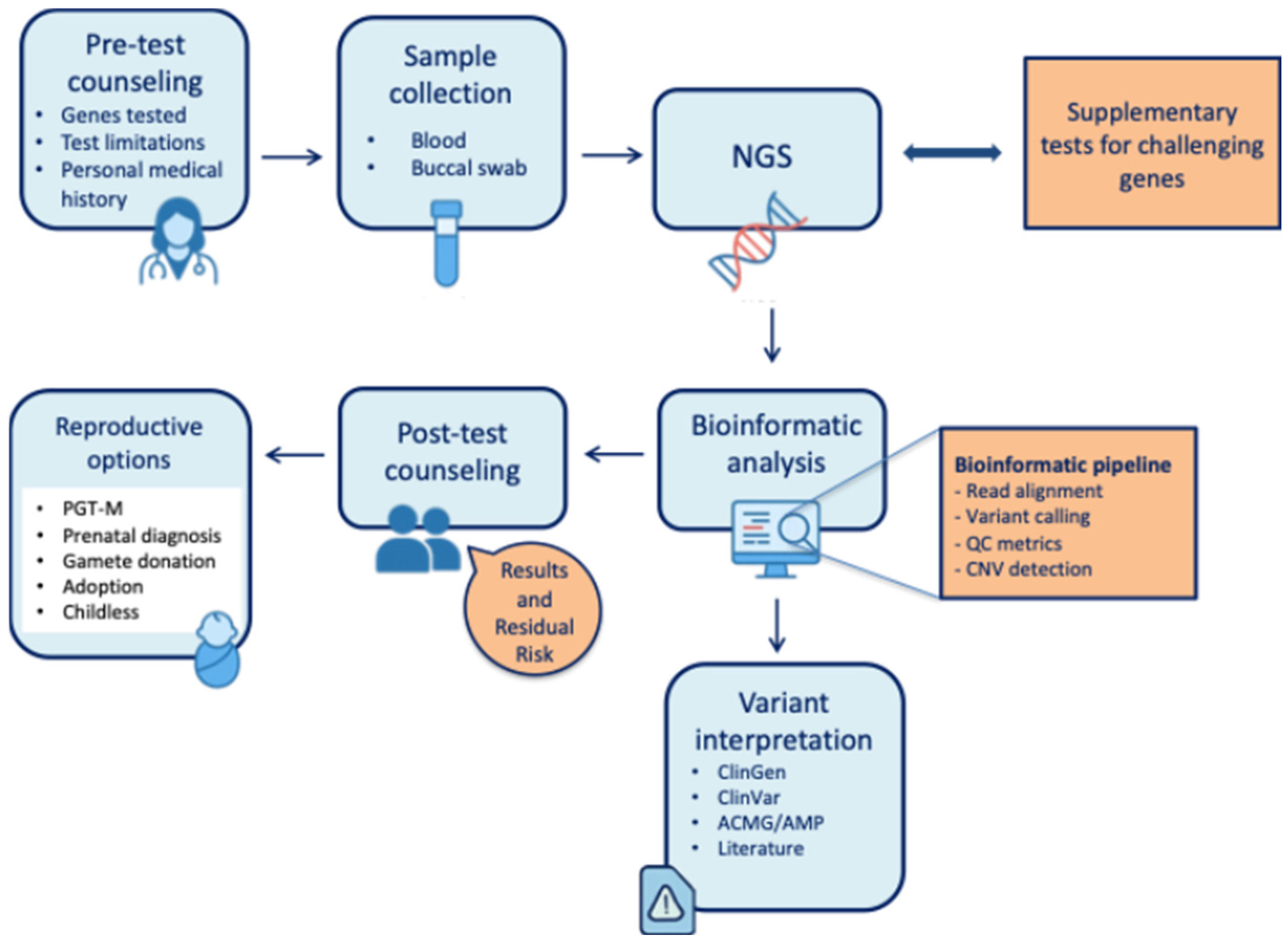

5. The Role of Genetic Counselling in CS Programs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henneman, L.; Borry, P.; Chokoshvili, D.; Cornel, M.C.; van El, C.G.; Forzano, F.; Hall, A.; Howard, H.C.; Janssens, S.; Kayserili, H.; et al. Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG 2016, 24, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroselli, S.; Poli, M.; Gatta, V.; Stuppia, L.; Capalbo, A. Preconception carrier screening and preimplantation genetic testing in the infertility management. Andrology 2025, 13, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaback, M.M. Population-based genetic screening for reproductive counseling: The Tay-Sachs disease model. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2000, 159, S192–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, P.; Capalbo, A.; Novelli, V.; Zuccarello, D.; Lonardo, F.; Giardina, E.; Calabrese, O.; Bizzoco, D.; Bianca, S.; Scarano, G.; et al. Considerazioni sull’utilizzo del Carrier Screening (CS) ed Expanded Carrier Screening (ECS) in Ambito Riproduttivo; Italian Society of Human Genetics, SIGU: Milan, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://sigu.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Considerazioni-sullutilizzo-del-Carrier-Screening-CS-ed-Expanded-Carrier-Screening-ECS-in-ambito-riproduttivo_rev20_07_2021.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Gregg, A.R.; Aarabi, M.; Klugman, S.; Leach, N.T.; Bashford, M.T.; Goldwaser, T.; Chen, E.; Sparks, T.N.; Reddi, H.V.; Rajkovic, A.; et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: A practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2021, 23, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capalbo, A.; de Wert, G.; Henneman, L.; Kakourou, G.; Mcheik, S.; Peterlin, B.; van El, C.; Vassena, R.; Vermeulen, N.; Viville, S.; et al. An ESHG-ESHRE survey on the current practice of expanded carrier screening in medically assisted reproduction. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 52, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, A.; Gabbiato, I.; Caroselli, S.; Picchetta, L.; Cavalli, P.; Lonardo, F.; Bianca, S.; Giardina, E.; Zuccarello, D. Considerations on the use of carrier screening testing in human reproduction: Comparison between recommendations from the Italian Society of Human Genetics and other international societies. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 2581–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Orton, K.; Kwan, E.; Faga, C.; Le, T.; Shaheen, R.; Nair, V.; Cliffe, S. Couple-Based Carrier Screening: How Gene and Variant Considerations Impact Outcomes. Genes 2025, 16, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiossi, C.E.; Goldberg, J.D.; Haque, I.S.; Lazarin, G.A.; Wong, K.K. Clinical Utility of Expanded Carrier Screening: Reproductive Behaviors of At-Risk Couples. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.H.; Gregg, A.R. Estimating yields of prenatal carrier screening and implications for design of expanded carrier screening panels. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2019, 21, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyser, A.; Singer, T.; Mullin, C.; Bristow, S.L.; Gamma, A.; Onel, K.; Hershlag, A. Comparing ethnicity-based and expanded carrier screening methods at a single fertility center reveals significant differences in carrier rates and carrier couple rates. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2019, 21, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, A.; Valero, R.A.; Jimenez-Almazan, J.; Pardo, P.M.; Fabiani, M.; Jiménez, D.; Simon, C.; Rodriguez, J.M. Optimizing clinical exome design and parallel gene-testing for recessive genetic conditions in preconception carrier screening: Translational research genomic data from 14,125 exomes. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, K.; He, W.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, L.; Hu, H.; Lu, G.; Lin, G.; Dong, C.; Zhang, V.W.; et al. Clinical Utility of Medical Exome Sequencing: Expanded Carrier Screening for Patients Seeking Assisted Reproductive Technology in China. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 943058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westemeyer, M.; Saucier, J.; Wallace, J.; Prins, S.A.; Shetty, A.; Malhotra, M.; Demko, Z.P.; Eng, C.M.; Weckstein, L.; Boostanfar, R.; et al. Clinical experience with carrier screening in a general population: Support for a comprehensive pan-ethnic approach. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2020, 22, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Capalbo, A.; Fabiani, M.; Caroselli, S.; Poli, M.; Girardi, L.; Patassini, C.; Favero, F.; Cimadomo, D.; Vaiarelli, A.; Simon, C.; et al. Clinical validity and utility of preconception expanded carrier screening for the management of reproductive genetic risk in IVF and general population. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 2050–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, T.S.; Schneider, E.; Boniferro, E.; Brockhoff, E.; Johnson, A.; Stoffels, G.; Feldman, K.; Grubman, O.; Cole, D.; Hussain, F.; et al. Barriers to completion of expanded carrier screening in an inner city population. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2023, 25, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, E.P.; Delatycki, M.B.; Archibald, A.D.; Tutty, E.; Caruana, J.; Halliday, J.L.; Lewis, S.; McClaren, B.J.; Newson, A.J.; Dive, L.; et al. Nationwide, Couple-Based Genetic Carrier Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Luo, J.; Li, J.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y. The effectiveness of expanded carrier screening based on next-generation sequencing for severe monogenic genetic diseases. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reches, A.; Ofen Glassner, V.; Goldstein, N.; Yeshaya, J.; Delmar, G.; Portugali, E.; Hallas, T.; Weinstein, A.; Kurolap, A.; Berkenstadt, M.; et al. Expanded targeted preconception screening panel in Israel: Findings and insights. J. Med. Genet. 2024, 61, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wen, J.; Zhang, H.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.; Liang, D.; Wu, L.; Li, Z. Comprehensive analysis of NGS-based expanded carrier screening and follow-up in southern and southwestern China: Results from 3024 Chinese individuals. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tan, J.; Jiang, Z.; Shao, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, P.; Luo, C.; Xu, Z. Expanded carrier screening for 224 monogenic disease genes in 1,499 Chinese couples: A single-center study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024, 63, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee Opinion No. 690 Summary: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, 595–596. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotakainen, R.; Järvinen, T.T.; Kettunen, K.; Anttonen, A.-K.; Jakkula, E. Estimation of carrier frequencies of autosomal and X-linked recessive genetic conditions based on gnomAD v4.0 data in different ancestries. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2025, 27, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, M.J.; Bashar, A.; Soman, V.; Nkrumah, E.A.F.; Al Mulla, H.; Darabi, H.; Wang, J.; Kiehl, P.; Sethi, R.; Dungan, J.; et al. Leveraging diverse genomic data to guide equitable carrier screening: Insights from gnomAD v.4.1.0. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Chen, G.; Lei, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Expanded carrier screening in Chinese patients seeking the help of assisted reproductive technology. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzin, M.J.; Hobbs, M.; Ellsworth, R.E.; Poll, S.; Aguilar, S.; Knezovich, J.; Faulkner, N.; Olsen, N.; Aradhya, S.; Burnett, L. Optimizing gene panels for equitable reproductive carrier screening: The Goldilocks approach. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2025, 27, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, H.; Behar, D.M.; Carmi, S.; Levy-Lahad, E. Preconception carrier screening yield: Effect of variants of unknown significance in partners of carriers with clinically significant variants. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicconardi, A.; Facchiano, A.; Fariselli, P.; Giordano, D.; Isidori, F.; Marabotti, A.; Martelli, P.L.; Pascarella, S.; Pinelli, M.; Pippucci, T.; et al. Resources and tools for rare disease variant interpretation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1169109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenbuch, R.; Shearer, C.A.; Kollasch, A.W.; Spinner, A.D.; Hopf, T.; van Niekerk, L.; Franceschi, D.; Dias, M.; Frazer, J.; Marks, D.S. Proteome-wide model for human disease genetics. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 3165–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. DeepMind’s new AlphaGenome AI tackles the ‘dark matter’ in our DNA. Nature 2025, 643, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminbeidokhti, M.; Qu, J.H.; Belur, S.; Cakmak, H.; Jaswa, E.; Lathi, R.B.; Sirota, M.; Snyder, M.P.; Yatsenko, S.A.; Rajkovic, A. Miscarriage risk assessment: A bioinformatic approach to identifying candidate lethal genes and variants. Hum. Genet. 2024, 143, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tise, C.G.; Byers, H.M. Genetics of recurrent pregnancy loss: A review. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 33, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, R.; Lek, M.; Cooper, S.T. Gene discovery informatics toolkit defines candidate genes for unexplained infertility and prenatal or infantile mortality. npj Genom. Med. 2019, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseldin, H.E.; AlAbdi, L.; Maddirevula, S.; Alsaif, H.S.; Alzahrani, F.; Ewida, N.; Hashem, M.; Abdulwahab, F.; Abuyousef, O.; Kuwahara, H.; et al. Lethal variants in humans: Lessons learned from a large molecular autopsy cohort. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Mu, J.; Wang, L. Genetic factors as potential molecular markers of human oocyte and embryo quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Sang, Q.; Wang, L. Genetic factors of oocyte maturation arrest: An important cause for recurrent IVF/ICSI failures. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.N. Expanded carrier screening: Counseling and considerations. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Arribas, E.; Herrer, R.; Serna, J. Pros and cons of implementing a carrier genetic test in an infertility practice. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 28, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danylchuk, N.R.; Cook, L.; Shane-Carson, K.P.; Cacioppo, C.N.; Hardy, M.W.; Nusbaum, R.; Steelman, S.C.; Malinowski, J. Telehealth for genetic counseling: A systematic evidence review. J. Genet. Couns. 2021, 30, 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Lee, S.-A.; Chung, H.-S.; Yun, J.Y.; Park, E.A.; So, M.-K.; Huh, J. Evaluating the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence to Support Genetic Counseling for Rare Diseases. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movaghar, A.; Page, D.; Brilliant, M.; Mailick, M. Advancing artificial intelligence-assisted pre-screening for fragile X syndrome. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.; García, S.A.; León, A.; Pastor, O. The promises and pitfalls of automated variant interpretation: A comprehensive review. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busnelli, A.; Ciani, O.; Caroselli, S.; Figliuzzi, M.; Poli, M.; Levi-Setti, P.E.; Tarricone, R.; Capalbo, A. Implementing preconception expanded carrier screening in a universal health care system: A model-based cost-effectiveness analysis. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2023, 25, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdaney, A.; Lichten, L.; Propst, L.; Mann, C.; Lazarin, G.A.; Jones, M.; Taylor, A.; Malinowski, J. Expanded carrier screening in the United States: A systematic evidence review exploring client and provider experiences. J. Genet. Couns. 2022, 31, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Panel/Number of Genes | Population | Technologies | % At-Risk Couples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghiossi et al., J Genet Couns (2018)—Clinical Utility of ECS [10] | 110 genes | Not specified (results 537 ARC) | NGS-based panel | 2.5% |

| Guo, M. H., & Gregg, A. R. (2019)—Estimating yields of prenatal carrier screening and implications for design of expanded carrier screening panels [11] | 415 genes | Data from gnomAD v2.0.2, based on 123,136 exome sequencing sample | Theoretical model based on Gene Carrier Rate (GCR) | 0.17% to 2.52% |

| Peyser, A. et al. (2019)—Comparing ethnicity-based and expanded carrier screening methods at a single fertility center reveals significant differences in carrier rates and carrier couple rates [12] | 104 genes (comparison with ACOG panel/ethnicity) | 4232 individuals | NGS-based panel | 1.2% |

| Capalbo et al., (2019)—Optimizing clinical exome design and parallel gene-testing for recessive genetic conditions in preconception carrier screening: Translational research genomic data from 14,125 exomes [13] | 114 genes-conditions | 14,125 analysis (5845 gamete donors and 8280 infertile patients) | Exome sequencing | 4.8% |

| Tong K. et al. (2022)—“Clinical Utility of Medical Exome Sequencing” (China) [14] | 4158 genes | 2234 couples | Medical Exome Sequencing | 9.80% |

| Westemeyer, M. et al., (2020)—Clinical experience with carrier screening in a general population: support for a comprehensive pan-ethnic approach [15] | 274 genes | 381,014 individuals | NGS-based panel | 2.28% |

| Capalbo A. et al., (2021)—Clinical validity and utility of preconception expanded carrier screening for the management of reproductive genetic risk in IVF and general population [16] | 20 genes | 3877 individuals | NGS based panel and qPCR | 2.6% |

| Strauss, T. S. et al., (2023)—Barriers to completion of expanded carrier screening in an inner city population [17] | 283 genes | 222 couples | NGS-based panel | 9.5% |

| Mackenzie’s Mission (Kirk, Archibald et al., NEJM—(2024)) [18] | 1281 genes (~750 diseases) | National program in Australia—10,038 couples enrolled | Exome sequencing and NGS panel | 1.9% |

| Zhang X, Chen Q, Li J et al.—(2024) The effectiveness of expanded carrier screening based on next-generation sequencing for severe monogenic genetic diseases [19] | 147 genes (155 diseases) | 1048 couples | NGS-based panel | 5.34% |

| Feldman et al., 2024—Expanded targeted preconception screening panel in Israel [20] | 357 genes (1487 variants) | 10,115 Israelis (6036 couples tested) | SNP-Array | 2.6% |

| Huang et al., 2024—Comprehensive analysis of NGS-based expanded carrier screening in southern/southwestern China [21] | 220 genes | 1512 couples | NGS-based panel | Not specified |

| Tan et al., 2024—Expanded carrier screening for 224 monogenic disease genes in 1499 Chinese couples [22] | 224 genes | 1499 couples (China) | NGS-based panel | 3.67% |

| Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Early identification of reproductive risk | Variable detection rates and residual risk |

| Expanded reproductive options | Interpretation issues related to variants of uncertain significance (VUS) |

| Reduction in incidence of severe recessive disorders | Psychological impact and complex reproductive decision-making |

| More equitable screening when panels are ancestry-independent | Cost and variability in access across healthcare systems |

| Supports personalized genetic counseling | Ethical and implementation considerations (consent, misinterpretation, integration in routine care) |

| Reduction in economic burden for recessive diseases healthcare |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pilenzi, L.; Scorrano, V.; Di Rado, S.; Buccolini, C.; Giansante, R.; Siciliani, L.; Stuppia, L.; Gatta, V.; Capalbo, A. Expanded Carrier Screening: Current Evidence and Future Directions in the Era of Population Genomics. Genes 2026, 17, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010058

Pilenzi L, Scorrano V, Di Rado S, Buccolini C, Giansante R, Siciliani L, Stuppia L, Gatta V, Capalbo A. Expanded Carrier Screening: Current Evidence and Future Directions in the Era of Population Genomics. Genes. 2026; 17(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010058

Chicago/Turabian StylePilenzi, Lucrezia, Vincenzo Scorrano, Sara Di Rado, Carlotta Buccolini, Roberta Giansante, Laura Siciliani, Liborio Stuppia, Valentina Gatta, and Antonio Capalbo. 2026. "Expanded Carrier Screening: Current Evidence and Future Directions in the Era of Population Genomics" Genes 17, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010058

APA StylePilenzi, L., Scorrano, V., Di Rado, S., Buccolini, C., Giansante, R., Siciliani, L., Stuppia, L., Gatta, V., & Capalbo, A. (2026). Expanded Carrier Screening: Current Evidence and Future Directions in the Era of Population Genomics. Genes, 17(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010058