Assembly, Characterization and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitogenome of Small-Leaved Eriobotrya seguinii (Maleae, Rosaceae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Sequencing Data Retrieving

2.2. Mitogenome Assembly and Gene Annotation

2.3. Repeat Sequence Analysis

2.4. Codon Usage

2.5. Prediction of RNA Editing Events and Nucleotide Diversity

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genomic Features of the E. seguinii Mitogenome

3.2. Characteristics of Repeat Sequences

3.3. Codon Usage Bias Analysis

3.4. RNA Editing Sites and Nucleotide Diversity

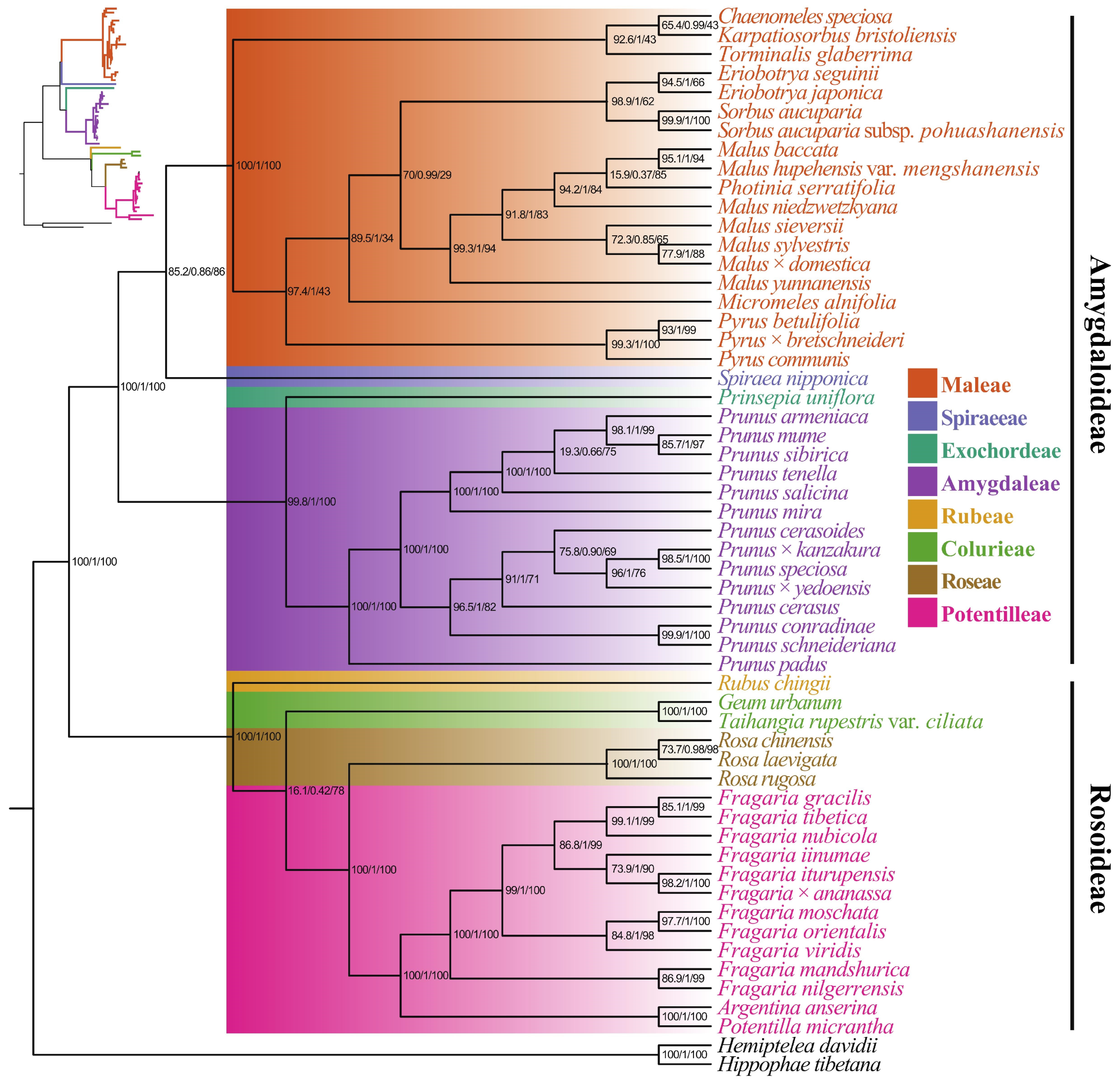

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCGs | Protein-coding genes |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| bp | base pair |

| A | Adenine |

| T | Thymine |

| G | Guanine |

| C | Cytosine |

| ORFs | Open reading frames |

References

- Gu, C.Z.; Spongberg, S.A. Eriobotrya Lindley. In Flora of China; Wu, Z.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2003; Volume 9, pp. 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Léveillé, H. Decades plantarum novarum. Repert. Spec. Nov. Regni Veg. 1912, 10, 431. Available online: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/7031#page/1/mode/1up (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Cardot, J. Rosacees Nouvelles D’Extreme-Orient (Suite). Notul. Syst. 1918, 3, 371–372. Available online: https://archive.org/details/biostor-266751 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Guillaumin, A. Observations Sur les Symplocos. Bull. Soc. Bot. France 1924, 71, 287. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00378941.1924.10836934 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- POWO. The Plants of the World Online Database. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2025. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Fay, M.F.; Christenhusz, M.J.M. Rosaceae. In The Global Flora: A Practical Flora to Vascular Plant Species of the World; Christenhusz, M.J.M., Fay, M.F., Byng, J.W., Eds.; Plant Gateway Ltd.: Bradford, UK, 2018; Volume 4, pp. 94–126. Available online: https://docslib.org/doc/7359289/global-flora-vol-4 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Liu, B.B.; Liu, G.N.; Hong, D.Y.; Wen, J. Eriobotrya belongs to Rhaphiolepis (Maleae, Rosaceae): Evidence from chloroplast genome and nuclear Ribosomal DNA Data. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, J.E. Notes sur quelques Rosacees asiatiques (III). Revision du genre Eriobotrya (Pomoideae). Adansonia 1965, 5, 537–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, C. Rosaceae. In The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. VI Flowering Plants-Dicotyledons Celastrales, oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales; Cornales, Ericales; Kubitzki, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 343–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Li, M.; Pathak, M.L.; Qaiser, M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, X.-F. A taxonomic revision of the genus Eriobotrya Lindl. (Rosaceae). Pak. J. Bot. 2022, 54, 985–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, A.A.; Pramanick, D.D.; Krishna, G.; Mao, A.A. (Eds.) Flora of India; Rosaceae to Neuradaceae; Botanical Survey of India: Kolkata, India, 2025; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.-H.; Ong, H.G.; Lee, J.-H.; Jung, E.-K.; Kyaw, N.-O.; Fan, Q.; Kim, Y.-D. A new broad-leaved species of loquat from Eastern Myanmar and its phylogenetic affinity in the genus Eriobotrya (Rosaceae). Phytotaxa 2021, 482, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaszewski, B.; Jankowska-Wróblewska, S.; Świło, K.; Burczyk, J. Phylogeny of Maleae (Rosaceae) Based on Complete Chloroplast Genomes Supports the Distinction of Aria, Chamaemespilus and Torminalis as Separate Genera, Different from Sorbus sp. Plants 2021, 10, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Qu, S.; Landrein, S.; Yu, W.B.; Xin, J.; Zhao, W.; Song, Y.; Tan, Y.; Xin, P. Increasing taxa sampling provides new insights on the phylogenetic relationship between Eriobotrya and Rhaphiolepis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 831206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Morales-Briones, D.F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, T.; Huang, C.H.; Guo, P.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Phylogenomics insights into gene evolution, rapid species diversification, and morphological innovation of the apple tribe (Maleae, Rosaceae). New Phytol. 2023, 240, 2102–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Li, M.; Shaw, J.M.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ahmad, M. New species, combinations and synonyms in Eriobotrya (Rosaceae). Phytotaxa 2025, 712, 031–046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Qu, S.; Zhu, W.; Li, Q.; Tan, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xin, P.; Song, Y. Chloroplast-genome-based insights into the systematic relationship of Eriobotrya (Rhaphiolepis). iScience 2025, 28, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, N.; Chen, F.; Shaw, J.M.H. Reassessing the Evolutionary Relationships of Eriobotrya and Rhaphiolepis (Rosaceae): Evidence from Micromorphology, Complete Nuclear Ribosomal DNA and Mitochondrial Genomic Data. Biology 2025, 14, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Tian, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z. Comparative Mitochondrial genome of the endangered Prunus pedunculata (Prunoideae, Rosaceae) in China: Characterization and phylogenetic analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1266797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Fu, D.; Zhao, B.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y. Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of mitochondrial genomes of hawthorn (Cratageus spp.) in Northeast China. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, P.; Xiang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, X.; Yin, Y.; Qin, L.; Yuan, T. Comparative analysis of the organelle genomes of seven Rosa species (Rosaceae): Insight into structural variation and phylogenetic position. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1584289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, R.; Qin, X.; Shen, X.; You, C. Morphological structure identification, comparative Mitochondrial genomics and population genetic analysis toward exploring interspecific variations and phylogenetic implications of Malus baccata ‘ZA’ and other species. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.; He, X.Y.; Li, W.Y. The Taihangia mitogenome provides new insights into its adaption and organelle genome evolution in Rosaceae. Planta 2025, 261, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, N.; Zeng, X.L.; Wu, J.C.; Lin, X.J.; Zheng, G.H. Phylogenetic relationships and characterizations of the complete mitochondrial genome of Eriobotrya japonica in southeast of China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2019, 5, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yü, T.T. Rosaceae (1). Spiraeoideae-Maloideae. In Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1974; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Peng, S.A.; Cai, L.H.; Fang, D.Q. The germplasm resources of the genus Eriobotrya with special reference on the origin of E. japonica Lindl. Acta Hort. Sinica 1990, 17, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Najafabadi, S.K.; Shahid, M.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, Y.; Wei, W.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Lin, S. Genetic relationships among Eriobotrya species revealed by genome-wide RAD sequence data. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G.F.; Yang, X.H.; Lin, S. Taxonomic studies using multivariate analysis of Eriobotrya based on morphological traits. Phytotaxa 2017, 302, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Pathak, M.L.; Memon, N.H.; Khan, S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, X.F. Morphological and Morphometric analysis of the genus Eriobotrya Lindl. (Rosaceae). J. Animal Plant Sci. 2021, 31, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.H.; Yang, X.H.; Lin, S.Q. Analysis of genetic relationships among Eriobotrya germplasm in China using ISSR markers. Acta Horticult. 2007, 750, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Liu, C.M.; Lin, S.Q. Genetic relationships in Eriobotrya species as revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers. Sci. Horti. 2009, 122, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lin, S.; Yang, X.H.; Hu, G.; Jiang, Y. Molecular phylogeny of Eriobotrya Lindl. (loquat) inferred from internal transcribed spacer sequences of nuclear ribosome. Pakistan J. Bot. 2009, 41, 185–193. Available online: http://pakbs.org/pjbot/PDFs/41(1)/PJB41(1)185.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yang, X.H.; Li, P.; Lin, S.Q.; Hu, G.B.; He, X.L. A preliminary phylogeny study of the Eriobotrya based on the nrDNA Adh sequences. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobot. 2012, 40, 233–237. Available online: https://ftp.notulaebotanicae.ro/index.php/nbha/article/view/7997/7036 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Chen, Z.J. ITS sequences from cultivars and some wild species of genus Eriobotrya. Guihaia 2017, 37, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Idrees, M.; Tariq, A.; Pathak, M.L.; Gao, X.F.; Sadia, S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zeng, F. Phylogenetic relationships of the genus Eriobotrya Lindl. (Rosaceae) based on ITS sequence. Pakistan J. Bot. 2020, 52, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Hui, W.; Mitra, L.P.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, X.F. Phylogenetic study of Eriobotrya (Rosaceae) based on combined cpDNA psbA-trnH and atpB-rbcl marker. J. Trop. Forest Sci. 2021, 33, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Milne, R.; Zhou, R.; Meng, K.; Yin, Q.; Guo, W.; Ma, Y.; Mao, K.; Xu, K.; Kim, Y.D.; et al. When tropical and subtropical congeners met: Multiple ancient hybridization events within Eriobotrya in the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, a tropical-subtropical transition area in China. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 31, 1543–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastP: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Boil. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Choudhuri, J.V.; Ohlebusch, E.; Schleiermacher, C.; Stoye, J.; Giegerich, R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 4633–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, S. Tandem repats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edera, A.A.; Small, I.; Milone, D.H.; Sanchez-Puerta, M.V. Deepred-Mt: Deep representation learning for predicting C-to-U RNA editing in plant mitochondria. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Tajima, F. DNA polymorphism detectable by restriction endonucleases. Genetics 1981, 97, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylus, D.; Altenhoff, A.; Majidian, S.; Sedlazeck, F.J.; Dessimoz, C. Inference of phylogenetic trees directly from raw sequencing reads using Read2Tree. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozewicki, J.; Li, S.; Amada, K.M.; Standley, D.M.; Katoh, K. MAFFT-DASH: Integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W5–W10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.Y.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Lei, H.P.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zou, H.; Wang, G.T.; Zhang, D. Using PhyloSuite for molecular phylogeny and tree-based analyses. Imeta. 2023, 2, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevigny, N.; Schatz-Daas, D.; Lotfi, F.; Gualberto, J.M. DNA repair and the stability of the plant mitochondrial genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardoya, R. Recent advances in understanding mitochondrial genome diversity. F1000Res 2020, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Zhao, M.; Lan, Q.; Peng, S.; Lin, F.; Li, Z. Comprehensive Assembly and Comparative Analysis of Chloroplast Genome and Mitogenome of Prunus salicina var. cordata. Genes 2025, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; Keeling, P.J. Mitochondrial and plastid genome architecture: Reoccurring themes, but significant differences at the extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10177–10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.F.; Zhao, Y.H.; Kong, X.J.; Khan, A.; Zhou, B.J.; Liu, D.M.; Kashif, M.H.; Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Zhou, R.Y. Complete sequence of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) mitochondrial genome and comparative analysis with the mitochondrial genomes of other plants. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, M.; Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Yu, R.; Han, X.; Chen, K.; Huang, A.; Chen, C.; et al. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of the bitter gourd (Momordica charantia). Plants 2023, 12, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Newton, K.J. Angiosperm mitochondrial genomes and mutations. Mitochondrion 2008, 8, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Teng, K.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Duan, L.; Zhang, H.; Wen, H.; Teng, W.; Yue, Y.; Fan, X. The first complete mitochondrial genome of Carex (C. breviculmis): A significantly expanded genome with highly structural variations. Planta 2023, 258, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Paterson, A.H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, D.; Qu, Y.; Jiang, A.; Ye, Q.; Ye, N. Corrigendum to analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. BioMed. Res. Int. 2016, 2019, 9691253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.P.; Hu, X.Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y.P.; Huang, J.L. Widespread impact of horizontal gene transfer on plant colonization of land. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Zhao, K.; Wu, J. Rearrangement and domestication as drivers of Rosaceae mitogenome plasticity. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasniak-Owczarek, M.; Kazmierczak, U.; Tomal, A.; Mackiewicz, P.; Janska, H. Deficiency of mitoribosomal S10 protein affects translation and splicing in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 11790–11806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, M.; Cognat, V.; Duchene, A.M.; Marechal-Drouard, L. A global picture of tRNA genes in plant genomes. Plant J. 2011, 66, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayne, C.K.; Lewis, T.A.; Stanley, R.E. Recent insights into the structure, function, and regulation of the eukaryotic transfer RNA splicing endonuclease complex. WIREs RNA 2022, 13, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Yu, J. Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chinese plum (Prunus salicina): Characterization of genome recombination and RNA editing sites. Genes 2021, 12, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, M.; McNally, J.; Henry, R.J. Evaluating the potential of SSR flanking regions for examining taxonomic relationships in the Vitaceae. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Lu, N.; Xu, Y.; He, C.; Lu, Z. Characterization and analysis of the mitochondrial genome of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) by comparative genomic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, K.; Busanello, C.; Viana, V.E.; Pegoraro, C.; Victoria, F.; Maia, L. An empirical analysis of mtSSRs: Could microsatellite distribution patterns explain the evolution of mitogenomes in plants? Funct. Integr. Genom. 2022, 22, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntal, H.; Sharma, V. In silico analysis of SSRs in mitochondrial genomes of plants. OMICS 2011, 15, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, H.; Zavala, A.; Musto, H. Codon usage in Chlamydia trachomatis is the result of strand-specific mutational biases and a complex pattern of selective forces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, S.T.; Udayasuriyan, V.; Bhadana, V. Codon usage bias. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wu, W.; Xin, Y.; Zeng, W. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitogenome of Rubus chingii var. suavissimus, an exceptional berry plant possessing sweet leaves. Front Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1504687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershkovitz, M.A.; Lewis, L.A. Deep-level diagnostic value of the rDNA-ITS region. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996, 13, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, D.B.; Warren, J.M.; Williams, A.M.; Wu, Z.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Chicco, A.J.; Havird, J.C. Cytonuclear integration and co-evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.S.; Evans, R.C.; Morgan, D.R.; Dickinson, T.A.; Arsenault, M.P. Phylogeny of Subtribe Pyrinae (Formerly the Maloideae, Rosaceae): Limited Resolution of a Complex Evolutionary History. Plant Syst. Evol. 2007, 266, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.K.; Chen, S.F.; Xu, K.W.; Zhou, R.C.; Li, M.W.; Dhamala, M.K.; Liao, W.B.; Fan, Q. Phylogenomic analyses based on genome-skimming data reveal cyto-nuclear discordance in the evolutionary history of Cotoneaster (Rosaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 158, 107083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.T.; Janssens, S.B.; Liu, B.B.; Yu, S.X. Phylogenomic conflict analyses of the plastid and mitochondrial genomes via deep genome skimming highlight their independent evolutionary histories: A case study in the cinquefoil genus Potentilla sensu lato (Potentilleae, Rosaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2024, 190, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, C.R.; Rieseberg, L.H. Reconstructing patterns of reticulate evolution in plants. American J. Bot. 2004, 91, 1700–1708. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4123861 (accessed on 5 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.D.; Jin, J.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Chase, M.W.; Soltis, D.E.; Li, H.T.; Yang, J.B.; Li, D.Z.; Yi, T.S. Diversification of Rosaceae since the Late Cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.D.; Herbon, L.A. Plant mitochondrial DNA evolues rapidly in structure, but slowly in sequence. J. Mol. Evol. 1998, 28, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mower, J.P.; Sloan, D.B.; Alverson, A.J. Plant Mitochondrial Genome Diversity: The Genomics Revolution. In Plant Genome Diversity; Wendel, J., Greilhuber, J., Dolezel, J., Leitch, I., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E. seguinii | E. japonica | |

|---|---|---|

| Total length (bp) | 372,899 | 434,980 |

| Total number of genes (unique) | 96 (71) | 67 (58; 71 *) |

| Protein-coding genes | 52 (47) | 41 (40; 41 *) |

| rRNA genes | 4 | 3 (3 *) |

| tRNA genes | 40 (20) | 23 (15; 22 *) |

| Genes with intron (s) | 13 | 8 |

| GC content (%) | 46 | 45.4 (37.80 *) |

| A (%) | 27.2 | 27.3 |

| G (%) | 23 | 22.6 |

| C (%) | 22.6 | 22.9 |

| T (%) | 27.2 | 27.3 |

| GenBank accessions | SRR35934444 | MN481990 |

| Category | Gene Groups | Genes in E. seguinii | Genes in E. japonica |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core genes | ATP synthase | atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, atp9-fragment * | atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp |

| Cytochrome C biogenesis | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc *, ccmFn | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc *, ccmFn | |

| Ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase | cob | cob | |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | cox1, cox2, cox2-fragment (2), cox3 | cox1, cox2, cox3 | |

| Maturase | matR | matR | |

| Variable genes | ORFs | ORF215, ORF216, ORF230, ORF230-fragment (3), ORF234, ORF300, ORF300-fragment *, ORF332, ORF354 | ORF215, ORF216, ORF230, ORF234, ORF300, ORF332, ORF354 |

| NADH dehydrogenase | nad1 **, nad1-fragment (2), nad2 **, nad2-fragment *, nad3, nad4 ***, nad4L, nad5 *, nad5-fragment (2) *, nad6, nad7 ****, nad9 | nad1 ****, nad2 ****, nad3, nad4 ***, nad4 (2) ***, nad4L, nad5 ***, nad5-fragment (2), nad6, nad7 ****, nad9 | |

| Transport membrane protein | mttB | mttB | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase | sdh4 | sdh4 | |

| Ribosomal Protein (LSU) | rpl5, rpl10 | rpl5, rpl10 | |

| Ribosomal Protein (SSU) | rps1, rps3, rps4, rps12, rps13, rps14 | rps1, rps3, rps4, rps12, rps13, rps14 | |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn5, rrn18, rrn5-fragment, rrn26 | rrn5, rrn18, rrn26 | |

| Transfer RNAs | trnK-UUU, trnS-UGA(2), trnS-GCU (2), trnW-CCA, trnP-GGG, trnP-UGG, trnP-UGG-fragment, trnF-GAA (3), trnC-GCA (2), trnN-GUU (2), trnY-GUA (2), trnE-UUC (4) i, trnD-GUC (2), trnTERM-UUA, trnnull-NNN(3), trnM-CAU (6) i, trnG-GCC (2), trnQ-UUG, trnH-GUG (2), trnT-UGU | trnK-TTT, trnS-GCT *, trnS-TGA, trnW-CCA, trnP-TGG, trnF-GAA (3), trnC-GCA, trnN-GTT, trnY-GTA, trnE-TTC (3), trnD-GTC, trnD-GTC (2), trnM-CAT (4), trnG-GCC, trnQ-TTG, trnH-GTG |

| Sequence Information | Mitochondrial Genome Sequences (mtDNA) |

|---|---|

| Number of sequences (n) | 56 |

| Number of Eriobotrya species (n) | 2 |

| Alignment length (bp) | 45,360 |

| Invariable sites (bp) | 10,831 |

| Variable sites (bp) | 1102 |

| Parsimony-information sites (bp) | 614 |

| Total number of mutations (bp) | 1176 |

| GC contents bp (%) | 43.1 |

| Total nucleotide diversity (Pi) | 0.01577 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Idrees, M.; Safiul Azam, F.M.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Lv, Y. Assembly, Characterization and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitogenome of Small-Leaved Eriobotrya seguinii (Maleae, Rosaceae). Genes 2026, 17, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010107

Idrees M, Safiul Azam FM, Li M, Zhang Z, Wang H, Lv Y. Assembly, Characterization and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitogenome of Small-Leaved Eriobotrya seguinii (Maleae, Rosaceae). Genes. 2026; 17(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdrees, Muhammad, Fardous Mohammad Safiul Azam, Meng Li, Zhiyong Zhang, Hui Wang, and Yunyun Lv. 2026. "Assembly, Characterization and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitogenome of Small-Leaved Eriobotrya seguinii (Maleae, Rosaceae)" Genes 17, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010107

APA StyleIdrees, M., Safiul Azam, F. M., Li, M., Zhang, Z., Wang, H., & Lv, Y. (2026). Assembly, Characterization and Comparative Analysis of the Complete Mitogenome of Small-Leaved Eriobotrya seguinii (Maleae, Rosaceae). Genes, 17(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010107