Optical Genome Mapping Enhances Structural Variant Detection and Refines Risk Stratification in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Cohort and Study Design

2.2. Sample Types and OGM Workflow

2.3. Additional Cytogenomics Work-Up

2.4. Next-Generation Sequencing and IGHV Somatic Hypermutation Analysis

2.5. Integrative Genomic Analyses Approach

2.6. Time-to-First-Treatment (TTFT) Assessment & Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

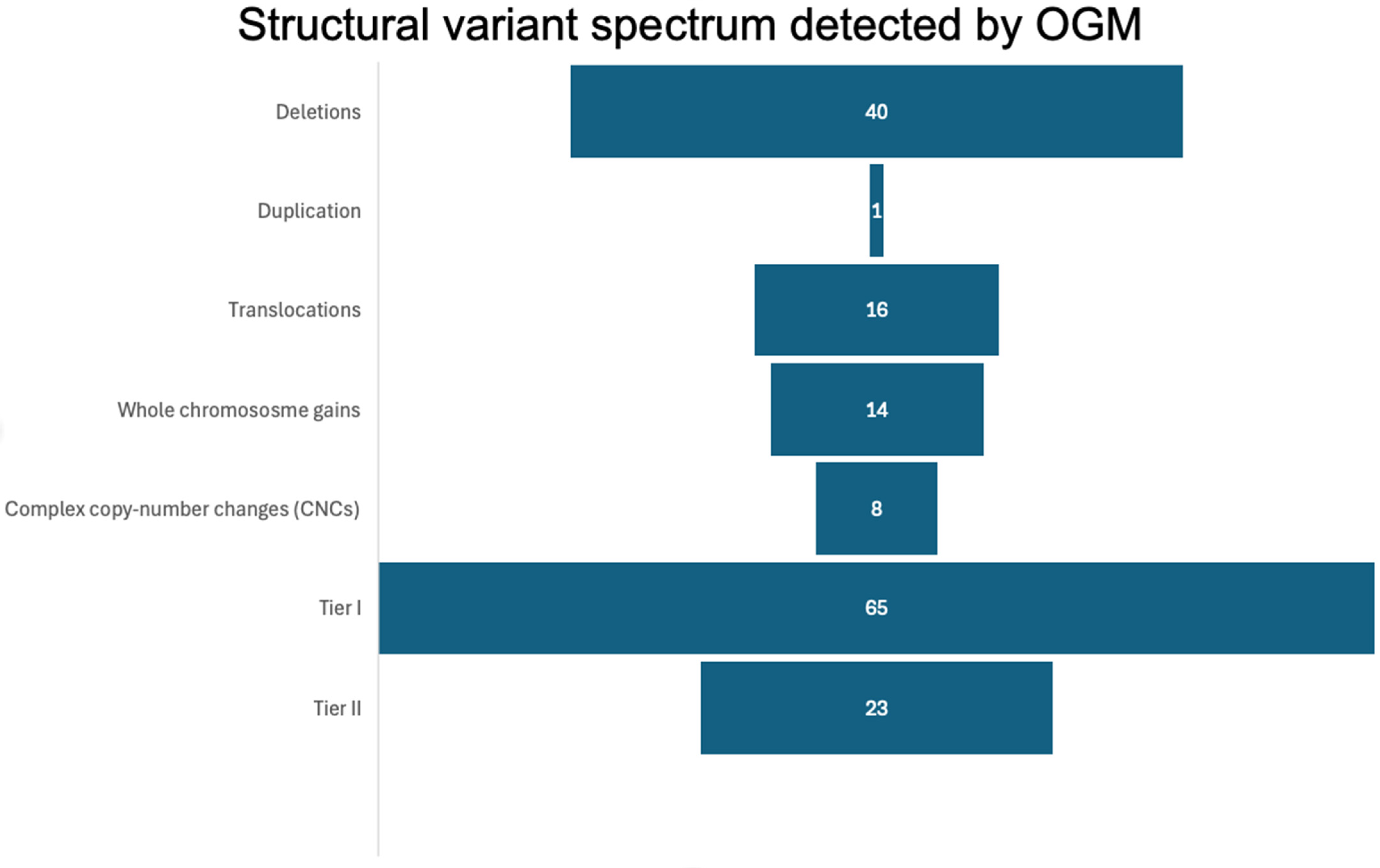

3.2. Global Structural Variant Landscape Identified by OGM

3.3. Deletion of 13q14 Presented as the Dominant Structural Variant with Heterogeneous Deletion Sizes

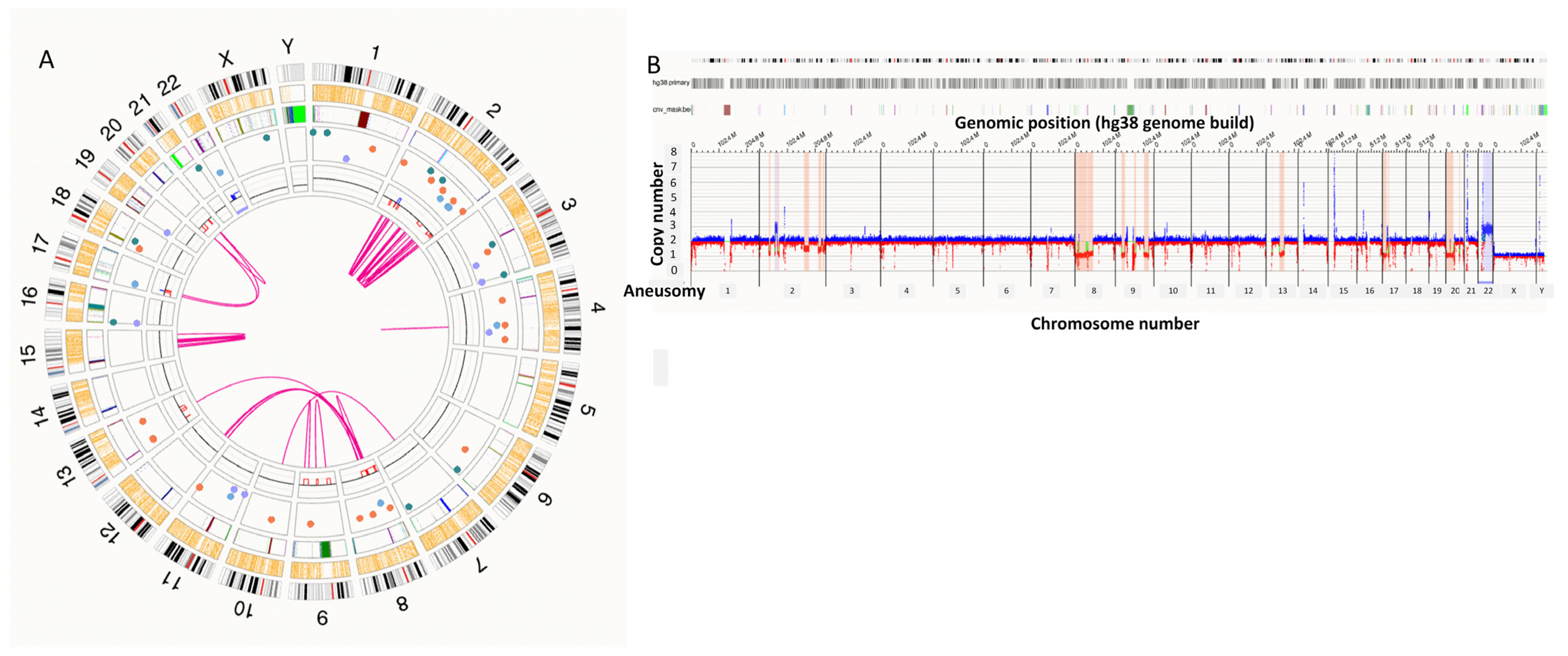

3.4. Co-Occurring High-Risk Structural Abnormalities

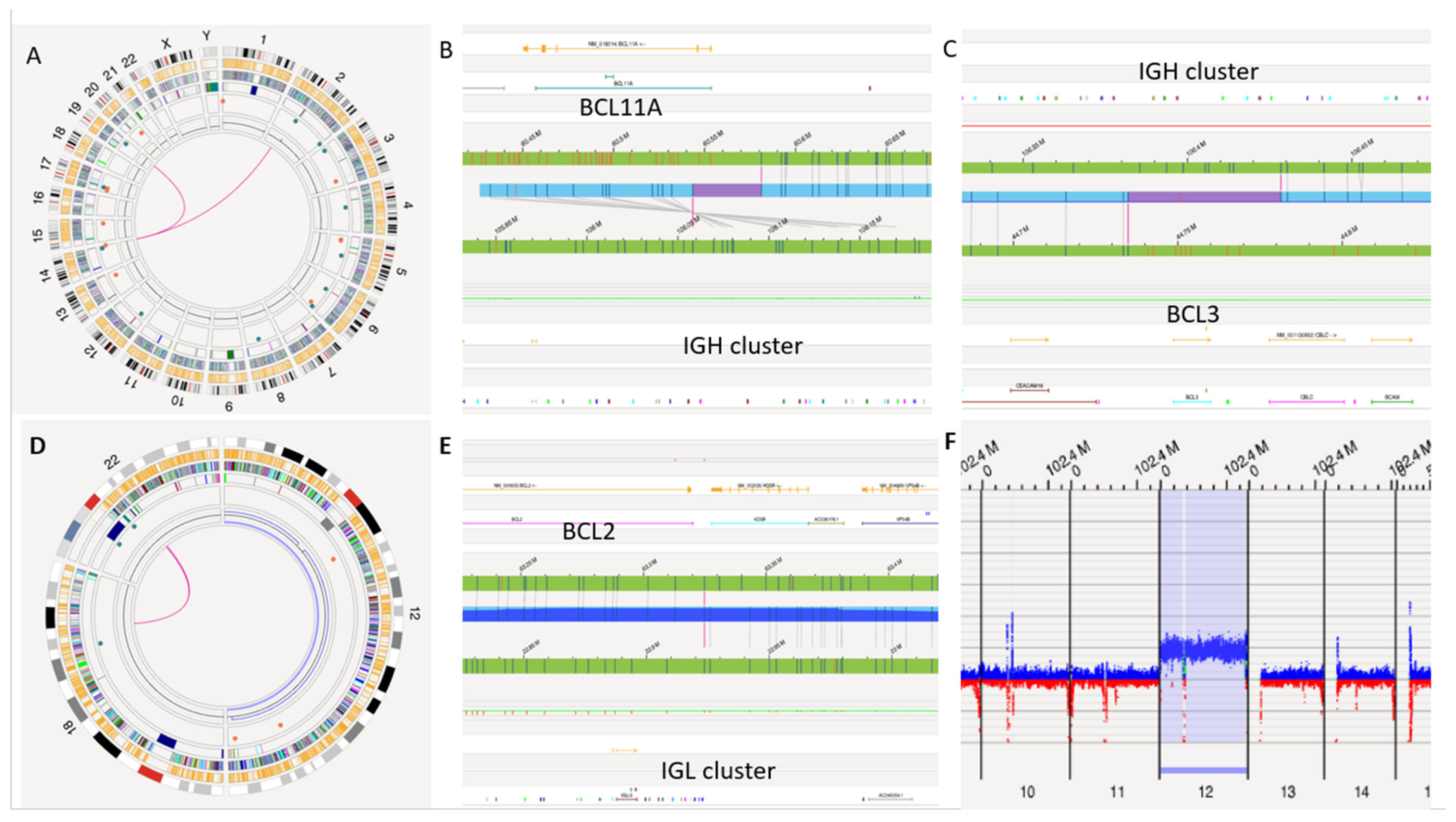

3.5. Rare CLL Rearrangements by OGM

3.6. Concordance Studies

3.7. OGM-Negative Cases

3.8. IGHV Somatic Hypermutation Status and Relationship to OGM Profiles

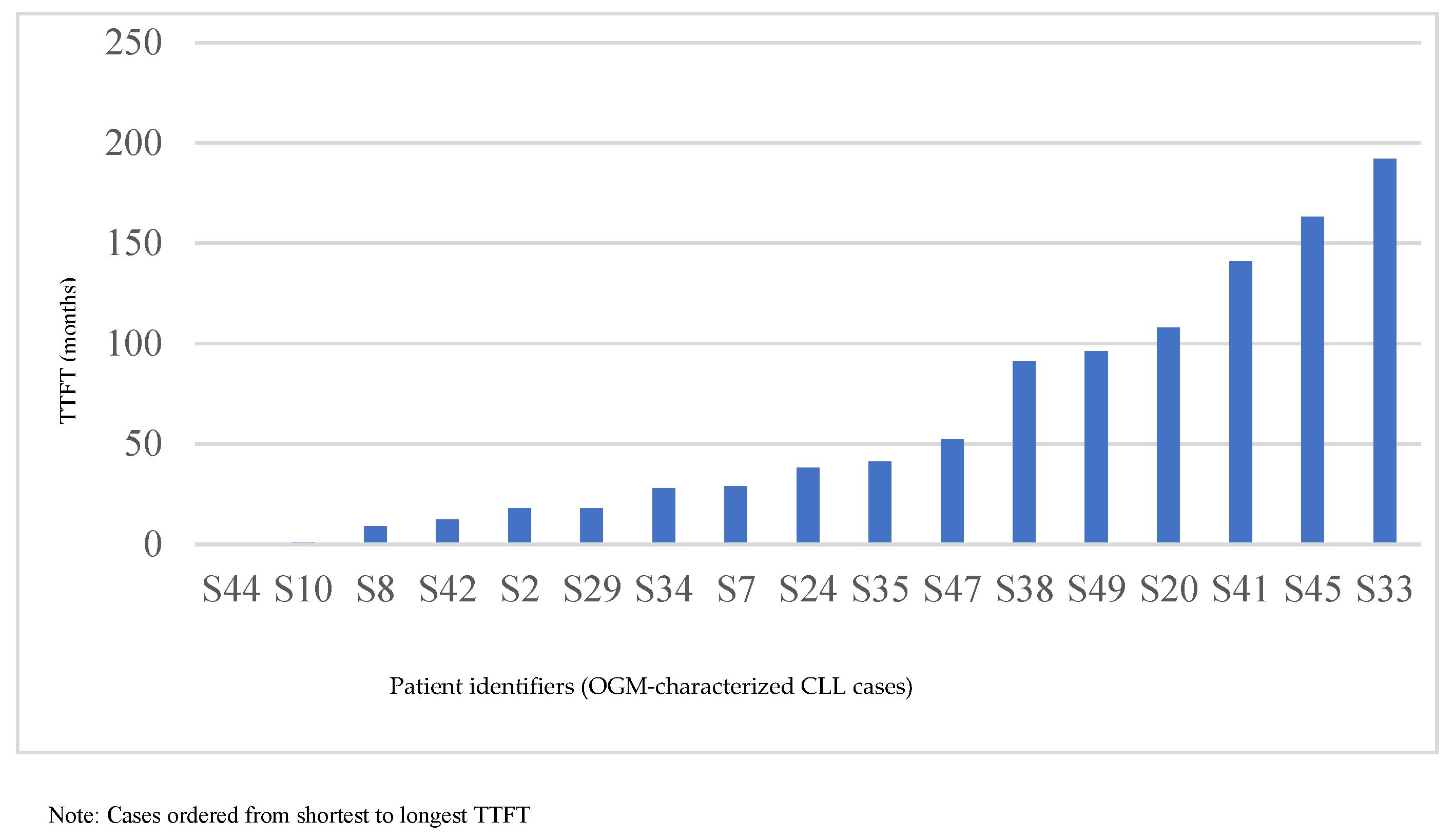

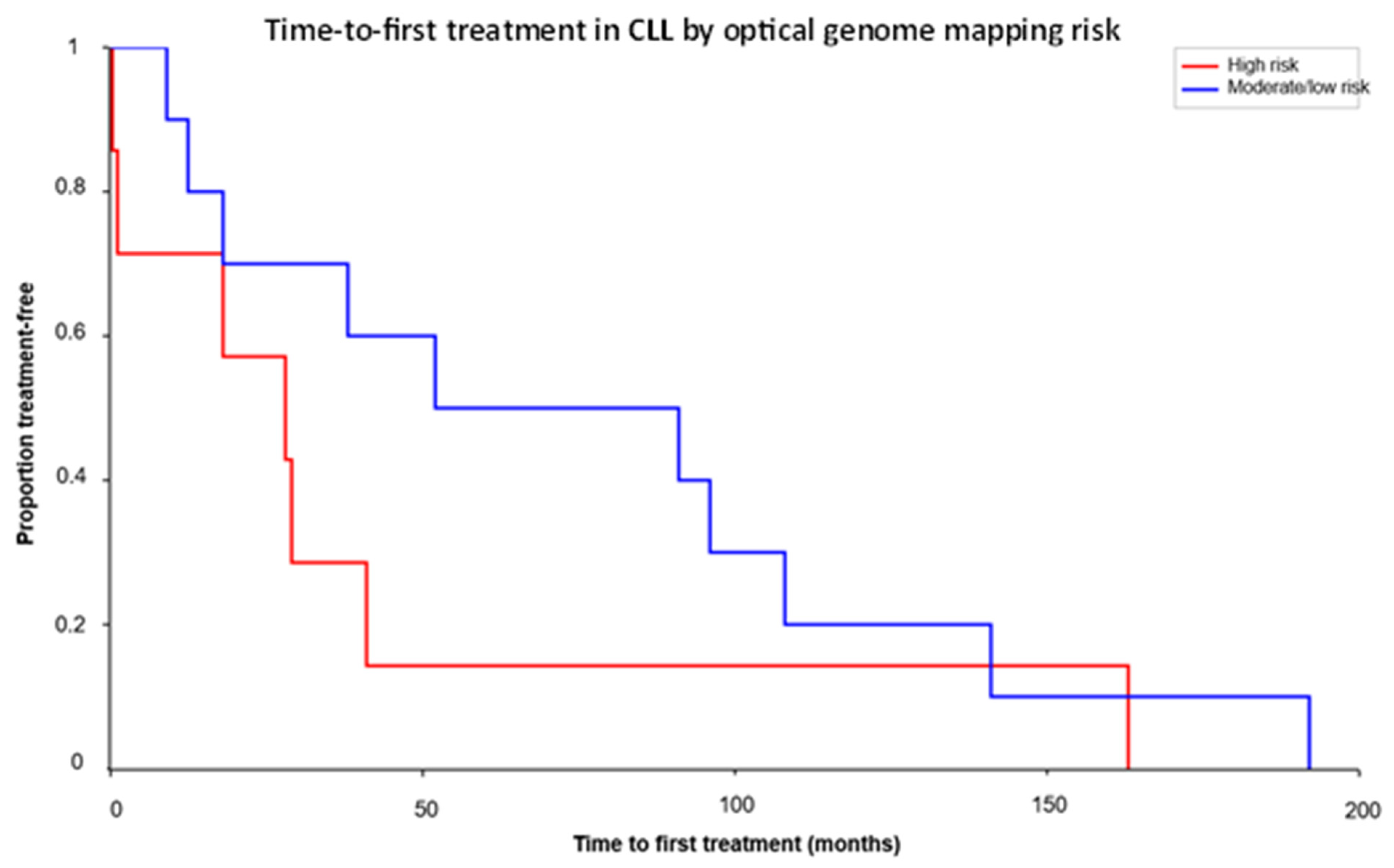

3.9. TTFT Analysis and Clinical Correlation

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Lesions and Genomic Complexity

4.2. Diagnostic and Clinical Impact of OGM

4.3. Integrated Genomic Risk and TTFT

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Döhner, H.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Benner, A.; Leupolt, E.; Kröber, A.; Bullinger, L.; Döhner, K.; Bentz, M.; Lichter, P. Genomic Aberrations and Survival in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1910–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenz, T.; Kröber, A.; Scherer, K.; Häbe, S.; Bühler, A.; Benner, A.; Döhner, H.; Stilgenbauer, S. Monoallelic TP53 Inactivation Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4473–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, G.; Dalla-Favera, R. The Molecular Pathogenesis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouillette, P.; Collins, R.; Shakhan, S.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Shedden, K.; Malek, S.N. The prognostic significance of various 13q14 deletions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6778–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez-Vicente, A.E.; Hernández, J.Á.; Lumbreras, E.; Sarasquete, M.E.; Martín, A.Á.; Benito, R.; Vicente-Gutiérrez, C.; Robledo, C.; de Las Heras, N.; et al. MiRNA expression profile of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with 13q deletion. Leuk. Res. 2016, 46, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausch, E.; Mertens, D.; Stilgenbauer, S. Genomic features: Impact on pathogenesis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2016, 39, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, T.J.; Davis, Z.; Gardiner, A.; Oscier, D.G.; Stevenson, F.K. Unmutated Ig V(H) Genes Are Associated with a Poor Prognosis in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 1999, 94, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damle, R.N.; Wasil, T.; Fais, F.; Ghiotto, F.; Valetto, A.; Allen, S.L.; Buchbinder, A.; Budman, D.; Dittmar, K.; Kolitz, J.; et al. Ig V Gene Mutation Status and CD38 Expression Define New Prognostic Subgroups in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 1999, 94, 1840–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xu, J.; Cao, S.; Wang, N.; Hao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Differential Impact of IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations on Clinical Outcomes in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Genetics 2025, 298–299, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveling, K.; Mantere, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Oorsprong, M.; van Beek, R.; Kater-Baats, E.; Pauper, M.; van der Zande, G.; Smeets, D.; Weghuis, D.O.; et al. Next-generation cytogenetics: Comprehensive assessment of 52 hematological malignancy genomes by optical genome mapping. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Sahajpal, N.S.; Neveling, K.; Rack, K.; Dewaele, B.; Olde Weghuis, D.; Stevens-Kroef, M.; Puiggros, A.; Mallo, M.; et al. A framework for the clinical implementation of optical genome mapping in hematologic malignancies. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 642–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Puiggros, A.; Granada, I.; Raca, G.; Rack, K.; Mallo, M.; Dewaele, B.; Smith, A.C.; Akkari, Y.; Levy, B.; et al. Integration of Optical Genome Mapping in the Cytogenomic and Molecular Work-Up of Hematological Malignancies: Expert Recommendations From the International Consortium for Optical Genome Mapping. Am. J. Hematol. 2025, 100, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.S.; Hughes, E.G.; Sukhadia, S.S.; Green, D.C.; Houde, B.E.; Tsongalis, G.J.; Tafe, L.J. Validation and Implementation of a Somatic-Only Tumor Exome for Routine Clinical Application. J. Mol. Diagn. 2024, 26, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.R.; A Bickford, M.; A Smuliac, N.; A Tonseth, K.; Murad, F.; Bao, J.; Wilson, D.N.; Steinmetz, H.B.; Wainman, L.M.; Donnely, L.L.; et al. IGL: CCND1 Detected by Optical Genome Mapping Revises Diagnosis of a B-Cell Lymphoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2025, 164, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosati, E.; Baldoni, S.; De Falco, F.; Del Papa, B.; Dorillo, E.; Rompietti, C.; Albi, E.; Falzetti, F.; Di Ianni, M.; Sportoletti, P. NOTCH1 aberrations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.; Banks, H.E.; Sargent, R.L.; Medeiros, L.J.; Abruzzo, L.V. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with t (14;18)(q32; q21). Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Reid, J.; Jeyakumar, D.; Semenova, K.; Kiran, N.; Lee, L.; Fleishman, A.; Rezk, S.; Zhao, X.; Quintero-Rivera, F. Unfavorable Disease Progression in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia with Concurrent t(6;9)(DEK::NUP214) or inv(16)(CBFB::MYH11). Cancer Genetics 2025, 298–299, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeksma, A.C.; Taylor, J.; Wu, B.; Gardner, J.R.; He, J.; Nahas, M.; Gonen, M.; Alemayehu, W.G.; Te Raa, D.; Walther, T.; et al. Clonal diversity predicts adverse outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2019, 33, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, D.; Rasi, S.; Spina, V.; Bruscaggin, A.; Monti, S.; Ciardullo, C.; Deambrogi, C.; Khiabanian, H.; Serra, R.; Bertoni, F.; et al. Integrated Mutational and Cytogenetic Analysis Identifies New Prognostic Subgroups in CLL. Blood 2013, 121, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, D.A.; Carter, S.L.; Stojanov, P.; McKenna, A.; Stevenson, K.; Lawrence, M.S.; Sougnez, C.; Stewart, C.; Sivachenko, A.; Wang, L.; et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell 2013, 152, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Martinez, P.; Wade, R.; Hockley, S.; Oscier, D.; Matutes, E.; Dearden, C.E.; Richards, S.M.; Catovsky, D.; Morgan, G.J. Mutational status of the TP53 gene as a predictor of response and survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from the LRF CLL4 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, X.S.; Pinyol, M.; Quesada, V.; Conde, L.; Ordóñez, G.R.; Villamor, N.; Escaramis, G.; Jares, P.; Beà, S.; González-Díaz, M.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing Identifies Recurrent Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia. Nature 2011, 475, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliakas, P.; Jeromin, S.; Iskas, M.; Puiggros, A.; Plevova, K.; Nguyen-Khac, F.; Davis, Z.; Rigolin, G.M.; Visentin, A.; Xochelli, A.; et al. Cytogenetic Complexity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Definitions, Associations, and Clinical Impact. Blood 2019, 133, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stilgenbauer, S.; Schnaiter, A.; Paschka, P.; Zenz, T.; Rossi, M.; Döhner, K.; Bühler, A.; Böttcher, S.; Ritgen, M.; Kneba, M.; et al. Gene Mutations and Treatment Outcome in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Results from the CLL8 Trial. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2014, 123, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Fangazio, M.; Rasi, S.; Vaisitti, T.; Monti, S.; Cresta, S.; Chiaretti, S.; Del Giudice, I.; Fabbri, G.; Bruscaggin, A.; et al. Disruption of BIRC3 associates with fludarabine chemorefractoriness in TP53 wild-type chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2012, 119, 2854–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, K.; Dalla-Favera, R. Germinal Centres and B-Cell Lymphomagenesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küppers, R. Mechanisms of B-Cell Lymphoma Pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiggros, A.; Blanco, G.; Espinet, B. Genetic Abnormalities in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Where We Are and Where We Go. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 435983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Reichard, K.K.; Rabe, K.G.; Hanson, C.A.; Call, T.G.; Ding, W.; Kenderian, S.S.; Muchtar, E.; Schwager, S.M.; Leis, J.F.; et al. IGH Translocations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Clinicopathologic Associations and Outcomes. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lawrence, M.S.; Wan, Y.; Stojanov, P.; Sougnez, C.; Stevenson, K.; Werner, L.; Sivachenko, A.; DeLuca, D.S.; Zhang, L.; et al. SF3B1 and Other Novel Cancer Genes in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcikova, J.; Tausch, E.; Rossi, D.; Sutton, L.A.; Soussi, T.; Zenz, T.; Kater, A.P.; Niemann, C.U.; Gonzalez, D.; Davi, F.; et al. ERIC recommendations for TP53 mutation analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia—Update on methodological approaches and results interpretation. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, D.A.; Tausch, E.; Taylor-Weiner, A.N.; Stewart, C.; Reiter, J.G.; Bahlo, J.; Kluth, S.; Bozic, I.; Lawrence, M.; Böttcher, S.; et al. Mutations Driving CLL and Their Evolution in Progression and Relapse. Nature 2015, 526, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierda, W.G.; Brown, J.; Abramson, J.S.; Awan, F.; Bilgrami, S.F.; Bociek, G.; Brander, D.; Cortese, M.; Cripe, L.; Davis, R.S.; et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strefford, J.C. The genomic landscape of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Biological and clinical implications. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, R.M.; Telang, B.; Soni, G.; Khalife, A. Overview of perspectives on cancer, newer therapies, and future directions. Oncol. Transl. Med. 2024, 10, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| Total Patients | 50 |

| Male | 25 |

| Female | 25 |

| Median Age at Diagnosis (Male) | 63 |

| Median Age at Diagnosis (Female) | 65 |

| CLL Cases | 47 |

| MBL Cases | 2 |

| MCL Case (Revised) | 1 |

| Sample ID | Sample Type | OGM Findings | FISH Findings | IGV Mutation Status | NGS Findings | Prognosis Impacted by OGM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | BM | Negative | Negative | Unmutated | Negative | No |

| S2 | PB | T1: del(11q)(ATM, BCRL3), del (13q), T2: del(18p), dup(15q)(MAP2K1, PML, IDH2), reciprocal t(13;21) | del (11q), del(13q) | Unmutated | N/A | Yes |

| S3 | PB | Negative | Negative | N/A | Negative | No |

| S4 | PB | T1: del(13q) | del(13q) | N/A | N/A | No |

| S5 | PB | T1: del(13q) | del(13q) | Mutated | T1: TP53 | No |

| S6 | BM | T1: t(11;22)(IGL::CCND1) | Extra copy of 11q13 | Mutated | T2:DNMT3A, NOTCH2, BIRC3, SMARCB1 | Yes |

| S7 | PB | T1: del (11q)(ATM, BIRC3) | del(11q) | Unmutated | Negative | Yes |

| S8 | BM | T1: del(13q) (RB1) | del(13q) | Mutated | Negative | Yes |

| S9 | PB | T1: del(13q), t(5;13) | del(13q) | Mutated | No T1 or T2 | Yes |

| S10 | PB | T1:t(2;14)(IGH::BCL11A), t(14;19)(IGH::BCL3), partial copy number gain on chromosome 12 | Negative | Unmutated | N/A | Yes |

| S11 | PB | T1: Trisomy 12 | Trisomy 12 | N/A | N/A | No |

| S12 | PB | T1: del(13q), Trisomy12, T2:de(l1p)(CSF3R) | del(13q), Trisomy 12 | Mutated | T1:NOTCH1 | Yes |

| S13 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1), T2:ins17q23.3(CD79B) | del(13q) | Mutated | N/A | Yes |

| S14 | PB | T1: del(13q) (RB1),T2: gains of chromosomes 3, 8q(MYC), and 18 | del(13q) | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| S15 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1), t(1;13), t(7;13), t(9;13) | del(13q) | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| S16 | PB | Negative | Negative | N/A | N/A | No |

| S17 | PB | T1: Bi and mono allelic del(13q) | del(13q) | Mutated | No T1 or T2 | No |

| S18 | PB | Negative | Negative | Unmutated | No T1 or T2 | No |

| S19 | BM | Negative | Negative | N/A | T1: SRSF2 | No |

| S20 | PB | T1: del(13q) (RB1), reciprocal translocation between 2p13, 2q36.3, and 13q | del(13q) | Mutated | T1:NOTCH1, BIRC3 | Yes |

| S21 | PB | T1: del(13q) | del(13q) | unmutated | T1:TP53 | No |

| S22 | PB | T1: del(13q) | del(13q) | Mutated | N/A | No |

| S23 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1) | del13q | Mutated | N/A | No |

| S24 | BM | No T1 or T2 | Negative | Unmutated | T1: NOTCH1 | No |

| S25 | PB | Negative | Negative | N/A | N/A | No |

| S26 | PB | T1: del(13q), interstitial del(17p) (TP53) | del(13q), del(17p) | Mutated | N/A | No |

| S27 | PB | T1: del(13q) | N/A | Mutated | Negative | Yes |

| S28 | PB | Negative | Negative | N/A | N/A | No |

| S29 | BM | No T1 or T2 | Trisomy 12 (low-level) | Unmutated | T1: NOTCH1 | No |

| S30 | PB | T1: Trisomy12 | Trisomy 12 | Unmutated | N/A | No |

| S31 | PB | T1: de(l13q) | del(13q) | Mutated | N/A | No |

| S32 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1) | del(13q) | Mutated | N/A | No |

| S33 | PB | T1: del(13q), reciprocal translocation between 13q14 and 21q22.2, T2: CN gain 5q34-q35 | del(13q) | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| S34 | PB | T1: del(17p), paracentric translocation/inversion involving 13q14, T2: complex CN change in 12p and 12q | del(17p) | unmutated | T1:TP53, NOTCH1 | Yes |

| S35 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1), del17p, complex CNC 9p&9q, T2: Complex CNC 2p, 2q, loss 8p | del(17p), del(13q) | N/A | T1:TP53 | Yes |

| S36 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1) | del(13q) | Mutated | Negative | No |

| S37 | PB | T1: Trisomy 12, t(18;22)(IGL::BCL2) | Trisomy 12 | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| S38 | BM | T1: del(11q)(ATM&BIRC3)(low level), del(13q), Monosomy 13, reciprocal t(13q;14q) (low level) | del(13q)(low level) | Mutated | No T1 or T2 | Yes |

| S39 | PB | T1: del(13q)(RB1) | del(13q) | Mutated | Negative | No |

| S40 | PB | T1: Trisomy12, del9p22 (MLLT3, CDKN2A) | Trisomy12 | unmutated | Negative | Yes |

| S41 | BM | T1: del(13q) | del(13q) | Mutated | No T1 or T2 | No |

| S42 | PB | Negative | Negative | Unmutated | N/A | No |

| S43 | PB | T1: Trisomy 12, reciprocal t(1q23;13q14), T2: gains of chromosomes 18 and 19 | Negative | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| S44 | PB | T1: del(13q), del(17p), T2: t(8:14), CN gain of 2p, 7p, and 18, CN loss 8p, 20q | Extra copy of IGH, del(17p), biallelic del(13q) | Unmutated | T1:TP53 | Yes |

| S45 | PB | T1: Trisomy 12, t(14:18) (IGH:BCL2) | Trisomy12 | Mutated | No T1 or T2 | Yes |

| S46 | PB | T1: del(11q)(ATM, BIRC3), del(13q) | del(11q), del(13q) | Unmutated | N/A | Yes |

| S47 | BM | Negative | Negative | Unmutated | T2: DNMT3A | No |

| S48 | PB | T1: trisomy12, del(13q) (RB1), t(14:18)(IGH:BCL2) | extra copy IGH, del(13q), trisomy 12 | Mutated | T1:NOTCH1 | Yes |

| S49 | PB | T1: del(13q) (RB1), T2: t(1:13) | del(13q) | Unmutated | T1: NOTCH1 | Yes |

| S50 | PB | T1 Trisomy 12, del(13q) | trisomy 12, del(13q) | Mutated | T1: NOTCH1 T2: MYD88 | No |

| Case | TTFT(Months) | OGM Results |

|---|---|---|

| S44 | 0.3 | T1: Trisomy 12, reciprocal t(1q23;13q14), T2: gains of chromosomes 18 and 19 |

| S10 | 1.1 | T1:t(2;14)(IGH::BCL11A), t(14;19)(IGH::BCL3), partial copy number gain on chromosome 12 |

| S8 | 9 | T1: de(13q) (RB1) |

| S42 | 12.4 | Negative |

| S2 | 18 | T1: del(11q)(ATM, BIRC3), del(13q), T2: del(18p), dup(15q22)(MAP2K1, PML, IDH2), reciprocal t(13;21) |

| S29 | 18 | No T1 or T2 |

| S34 | 28 | T1: del(17p), paracentric translocation/inversion involving 13q14, T2: complex CNC in 12p and 12q |

| S7 | 29 | T1: del(11q)(ATM, BIRC3) |

| S24 | 38 | No T1 or T2 |

| S35 | 41 | T1: del(13q)(RB1), del(17p), complex CNC 9p&9q, T2: Complex CNCs 2p, 2q, loss 8p |

| S47 | 52 | Negative |

| S38 | 91 | T1: del (11q)(ATM&BIRC3)(low level), del(13q), Monosomy 13, reciprocal t(13q;14q) (low level) |

| S49 | 96 | T1: del(13q) (RB1), T2: t(1:13) |

| S20 | 108 | T1: del(13q) (RB1), reciprocal translocation between 2p13, 2q36, and 13q |

| S41 | 141 | T1: del(13q) |

| S45 | 163 | T1: Trisomy 12, t(14:18) (IGH::BCL2) |

| S33 | 192 | T1: del(13q), reciprocal translocation between 13q14 and 21q22.2, T2: CN gain 5q34-q35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, S.R.; Bickford, M.A.; Smuliac, N.A.; Tonseth, K.A.; Bao, J.; Murad, F.; Domínguez Vigil, I.G.; Steinmetz, H.B.; Wainman, L.M.; Shah, P.; et al. Optical Genome Mapping Enhances Structural Variant Detection and Refines Risk Stratification in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Genes 2026, 17, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010106

Chakraborty SR, Bickford MA, Smuliac NA, Tonseth KA, Bao J, Murad F, Domínguez Vigil IG, Steinmetz HB, Wainman LM, Shah P, et al. Optical Genome Mapping Enhances Structural Variant Detection and Refines Risk Stratification in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Genes. 2026; 17(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Soma Roy, Michelle A. Bickford, Narcisa A. Smuliac, Kyle A. Tonseth, Jing Bao, Farzana Murad, Irma G. Domínguez Vigil, Heather B. Steinmetz, Lauren M. Wainman, Parth Shah, and et al. 2026. "Optical Genome Mapping Enhances Structural Variant Detection and Refines Risk Stratification in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia" Genes 17, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010106

APA StyleChakraborty, S. R., Bickford, M. A., Smuliac, N. A., Tonseth, K. A., Bao, J., Murad, F., Domínguez Vigil, I. G., Steinmetz, H. B., Wainman, L. M., Shah, P., Bengtson, E. M., PonnamReddy, S., Harmon, G. A., Donnelly, L. L., Tafe, L. J., Karrs, J. X., Kaur, P., & Khan, W. A. (2026). Optical Genome Mapping Enhances Structural Variant Detection and Refines Risk Stratification in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Genes, 17(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010106