Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Oncology: Navigating Between Therapeutic Delivery and Tumor Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

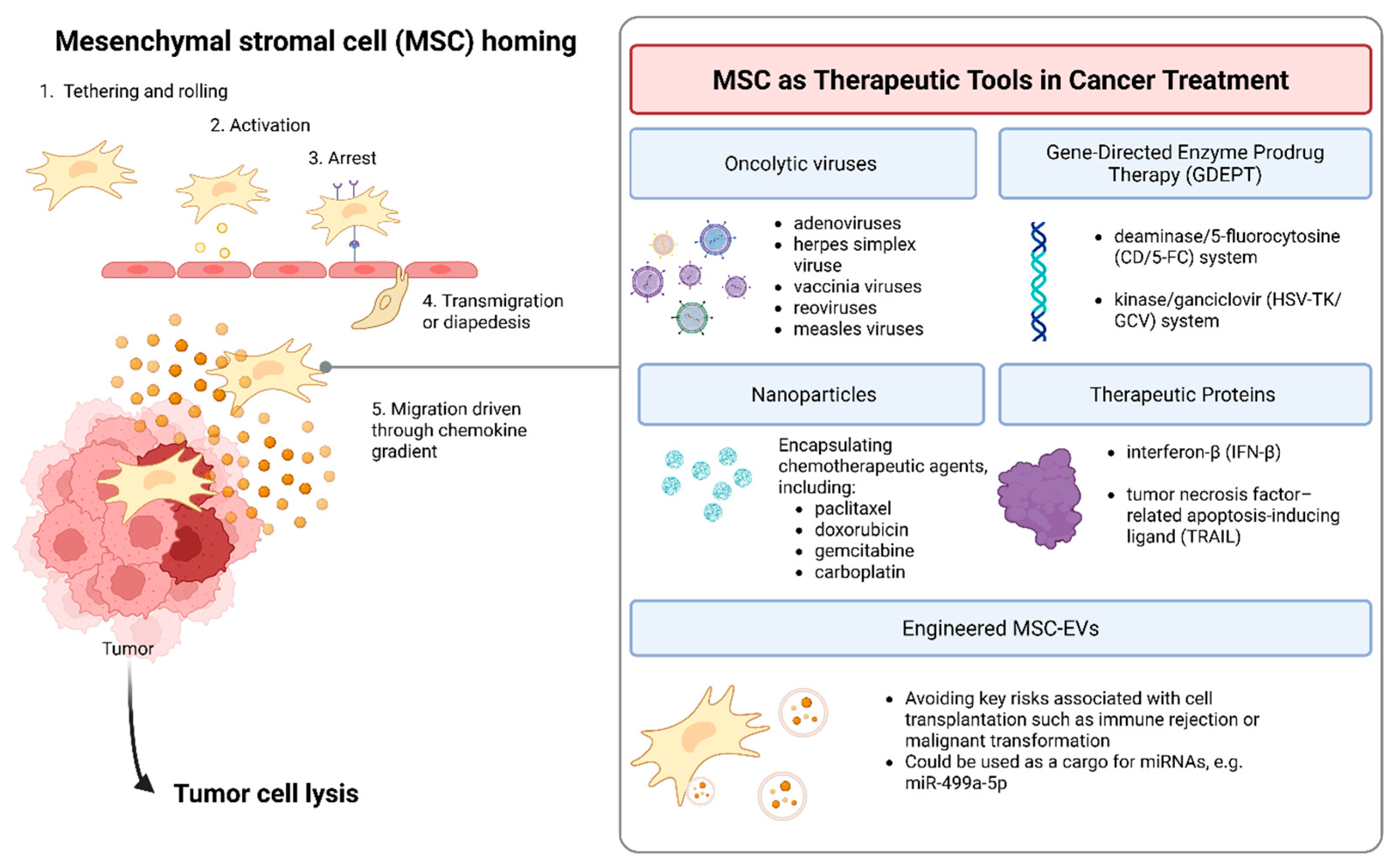

2. MSCs as Therapeutic Tools in Cancer Treatment

2.1. Oncolytic Viruses

2.2. Gene-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy (GDEPT)

2.3. Nanoparticles

2.4. Ex Vivo Gene Therapy and Therapeutic Proteins Delivery

2.5. Engineered MSC-EVs

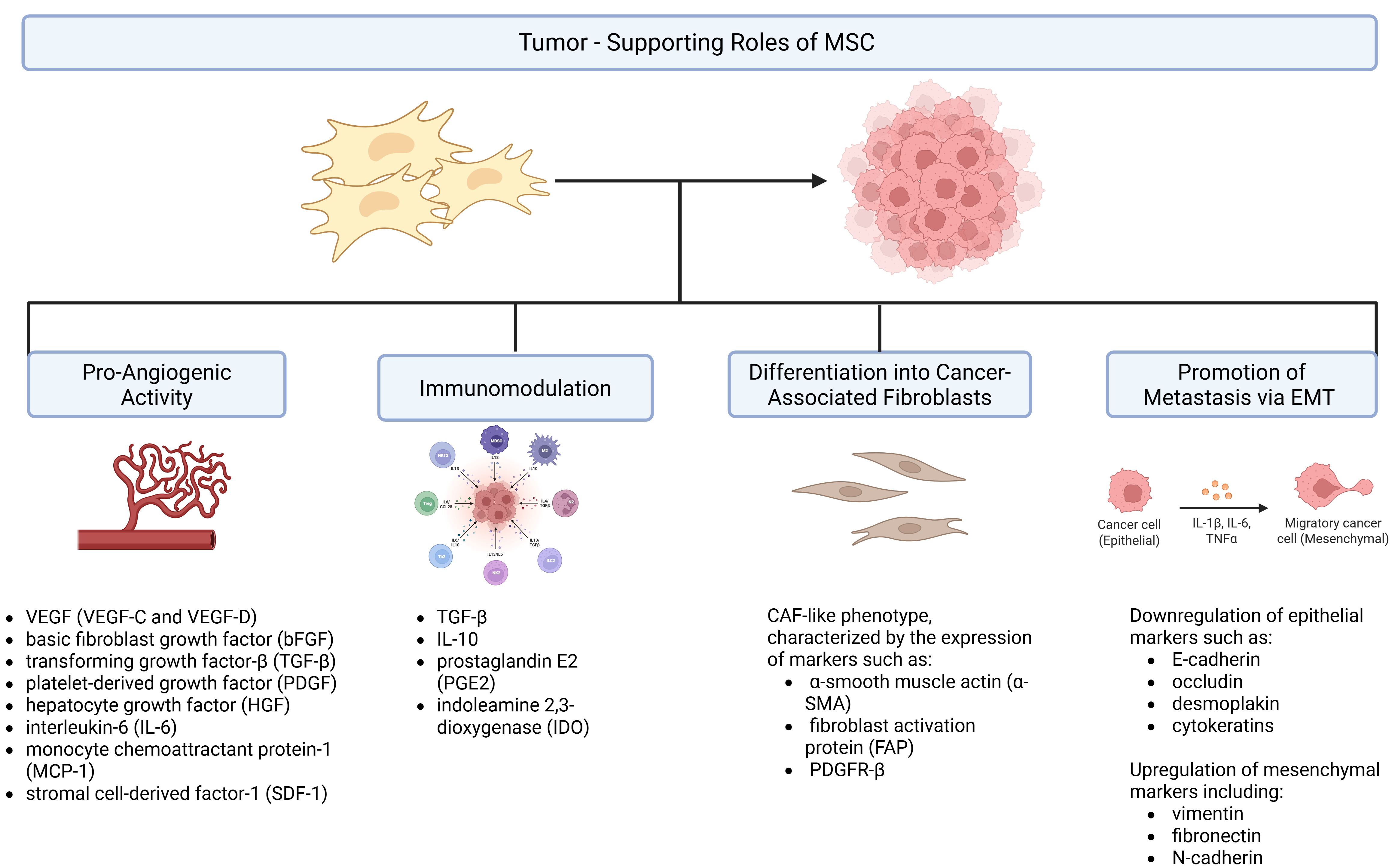

3. Potential Risks and Tumor-Promoting Effects of MSC-Based Therapies

3.1. Pro-Angiogenic Activity

3.2. Immunomodulation

3.3. Differentiation into Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

3.4. Promotion of Metastasis via EMT

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| AD-MSCs | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells |

| ATMP | Advanced therapy medicinal product |

| B-ALL | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| bFGF | Basic fibroblast growth factor |

| BM-MSC | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cell |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (stromal cell-derived factor-1, SDF-1) |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| GDEPT | Gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HE | Hospital exemption |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha |

| HLA-DR | Human leukocyte antigen—DR isotype |

| HSV-TK | Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| IFN-β | Interferon-beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| ITGA5 | Integrin alpha-5 |

| LLC | Lewis lung carcinoma |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MET | Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition |

| MNP | Magnetic nanoparticle |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell |

| MSC-EV | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle |

| NK | Natural killer (cell) |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| NTR | Nitroreductase |

| OV / OVs | Oncolytic virus / oncolytic viruses |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PDGFR-β | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PLGA | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) |

| PNP | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase |

| SDF-1 | Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL12) |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| T-VEC | Talimogene laherparepvec |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| TK | Thymidine kinase |

| TKA168H | HSV-TK mutant variant TKA168H |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Berebichez-Fridman, R.; Montero-Olvera, P.R. Sources and Clinical Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: State-of-the-Art Review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e264–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies: Immunomodulatory Properties and Clinical Progress. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.C.; Shyu, W.C.; Lin, S.Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkholt, L.; Flory, E.; Jekerle, V.; Lucas-Samuel, S.; Ahnert, P.; Bisset, L.; Büscher, D.; Fibbe, W.; Foussat, A.; Kwa, M.; et al. Risk of Tumorigenicity in Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Based Therapies: Bridging Scientific Observations and Regulatory Viewpoints. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Allickson, J. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy: Progress to Date and Future Outlook. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Fresnedo, A.; Al-Kharboosh, R.; Twohy, E.L.; Basil, A.N.; Szymkiewicz, E.C.; Zubair, A.C.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Durand, N.; Dickson, D.W.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; et al. Phase 1, Dose Escalation, Nonrandomized, Open-Label, Clinical Trial Evaluating the Safety and Preliminary Efficacy of Allogenic Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Clinical Trial Protocol. Neurosurg. Pract. 2023, 4, e00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Xia, Y.; Yu, T.; Tang, M.; Meng, K.; Yin, L.; Yang, Y.; Shen, L.; et al. The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer and Prospects for Their Use in Cancer Therapeutics. MedComm 2024, 5, e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.; Liu, D.D.; Thakor, A.S. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Homing: Mechanisms and Strategies for Improvement. iScience 2019, 15, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yu, S.; Liu, H.; Liao, N.; Liu, X. Enhancing Mesenchymal Stem Cell Survival and Homing Capability to Improve Cell Engraftment Efficacy for Liver Diseases. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L. The Heterogeneity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: An Important Issue to Be Addressed in Cell Therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różycka-Baczyńska, A.M.; Stepaniec, I.; Warzycha, M.; Zdolińska-Malinowska, I.; Oldak, T.; Rozwadowska, N.; Kolanowski, T.J. Development of a Novel Gene Expression Panel for the Characterization of MSCs for Increased Biological Safety. J. Appl. Genet. 2024, 65, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsvik, A.; Røsland, G.V.; Svendsen, A.; Molven, A.; Immervoll, H.; McCormack, E.; Lønning, P.E.; Primon, M.; Sobala, E.; Tonn, J.C.; et al. Spontaneous Malignant Transformation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reflects Cross-Contamination: Putting the Research Field on Track—Letter. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 6393–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi Darestani, N.; Gilmanova, A.I.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Zekiy, A.O.; Ansari, M.J.; Zabibah, R.S.; Jawad, M.A.; Al-Shalah, S.A.J.; Rizaev, J.A.; Alnassar, Y.S.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Released Oncolytic Virus: An Innovative Strategy for Cancer Treatment. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Gao, J.; Pang, X.; Wu, K.; Yang, S.; Wei, H.; Hao, Y. Formulation-Optimized Oncolytic Viruses: Advancing Systemic Delivery and Immune Amplification. J. Control. Release 2025, 383, 113822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, P.F.; Pala, L.; Conforti, F.; Cocorocchio, E. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-vec): An Intralesional Cancer Immunotherapy for Advanced Melanoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parato, K.A.; Senger, D.; Forsyth, P.A.J.; Bell, J.C. Recent Progress in the Battle between Oncolytic Viruses and Tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, W.; Qian, X.; Dunmall, L.C.; Liu, F.; Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Song, D.; Liu, D.; Ma, L.; Qu, Y.; et al. Non-Secreting IL12 Expressing Oncolytic Adenovirus Ad-TD-nsIL12 in Recurrent High-Grade Glioma: A Phase I Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F.F.; Bruner, J.M.; Fuller, G.N.; Aldape, K.; Prados, M.D.; Chang, S.; Berger, M.S.; McDermoff, M.W.; Kunwar, S.M.; Junck, L.R.; et al. Phase I Trial of Adenovirus-Mediated P53 Gene Therapy for Recurrent Glioma: Biological and Clinical Results. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin Ly, C.Y.; Kunnath, A.P. Application of Gene-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy in Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Biomed. Res. Pract. 2021, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kale, V.; Chen, M. Gene-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy. AAPS J. 2015, 17, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, I.; Touati, W.; Beaune, P.; De Waziers, I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells as Cellular Vehicles for Prodrug Gene Therapy against Tumors. Biochimie 2014, 104, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu-Duvaz, I.; Spooner, R.; Marais, R.; Springer, C.J. Gene-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 1998, 9, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordhuis, P.; Holwerda, U.; van der Wilt, C.L.; van Groeningen, C.J.; Smid, K.; Meijer, S.; Pinedo, H.M.; Peters, G.J. 5-Fluorouracil Incorporation into RNA and DNA in Relation to Thymidylate Synthase Inhibition of Human Colorectal Cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.-Y.; Jung, J.-H.; Kim, A.A.; Marasini, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, S.-S.; Suh-Kim, H. Combined Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Carrying Cytosine Deaminase Gene with 5-Fluorocytosine and Temozolomide in Orthotopic Glioma Model. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oishi, T.; Ito, M.; Koizumi, S.; Horikawa, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamagishi, S.; Yamasaki, T.; Sameshima, T.; Suzuki, T.; Sugimura, H.; et al. Efficacy of HSV-TK/GCV System Suicide Gene Therapy Using SHED Expressing Modified HSV-TK against Lung Cancer Brain Metastases. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 26, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Sadia, H.; Ali Shah, S.Z.; Khan, M.N.; Shah, A.A.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, M.F.; Bibi, H.; Bafakeeh, O.T.; Ben Khedher, N.; et al. Classification, Synthetic, and Characterization Approaches to Nanoparticles, and Their Applications in Various Fields of Nanotechnology: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Rajan, R.A.; Balasubramaniyam, S.; Elumalai, K. Nano Delivery Systems in Stem Cell Therapy: Transforming Regenerative Medicine and Overcoming Clinical Challenges. Nano TransMed 2025, 4, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.W.; Hsiao, J.K.; Liu, H.M.; Wu, C.H. Characterization of an Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Labelling and MRI-Based Protocol for Inducing Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Neural-like Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebinger, M.R.; Kyrtatos, P.G.; Turmaine, M.; Price, A.N.; Pankhurst, Q.; Lythgoe, M.F.; Janes, S.M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Homing to Pulmonary Metastases Using Biocompatible Magnetic Nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8862–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Yu, D.; Tsai, H.M.; Morshed, R.A.; Kanojia, D.; Lo, L.W.; Leoni, L.; Govind, Y.; Zhang, L.; Aboody, K.S.; et al. Dynamic in Vivo SPECT Imaging of Neural Stem Cells Functionalized with Radiolabeled Nanoparticles for Tracking of Glioblastoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Jeong, C.H.; Woo, J.S.; Ryu, C.H.; Lee, J.H.; Jeun, S.S. In Vivo Near-Infrared Imaging for the Tracking of Systemically Delivered Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Tropism for Brain Tumors and Biodistribution. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 11, 3079–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, S.; Guo, J.; Alahdal, M.; Cao, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Y.; Sun, M.; Mo, R.; et al. Targeted Delivery of Doxorubicin by Nano-Loaded Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Lung Melanoma Metastases Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layek, B.; Sadhukha, T.; Panyam, J.; Prabha, S. Nano-Engineered Mesenchymal Stem Cells Increase Therapeutic Efficacy of Anticancer Drug through True Active Tumor Targeting. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Lv, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Loaded with Paclitaxel-Poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) Nanoparticles for Glioma-Targeting Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 5231–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente-Gómez, N.; Martínez-Mingo, M.; Díaz-Riascos, Z.V.; García-Prats, B.; de la Iglesia, I.; Dhanjani, M.; García-Soriano, D.; Campos, L.A.; Mancilla-Zamora, S.; Salas, G.; et al. Gemcitabine and miRNA34a Mimic Codelivery with Magnetic Nanoparticles Enhanced Anti-Tumor Effect against Pancreatic Cancer. J. Control. Release 2025, 383, 113791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, J.J.; Cabaña-Muñoz, M.E. Nanoparticles and Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Therapy for Cancer Treatment: Focus on Nanocarriers and a si-RNA CXCR4 Chemokine Blocker as Strategies for Tumor Eradication In Vitro and In Vivo. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y. Cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and cytotoxicity of nanomaterials. Small 2011, 7, 1322–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.Q.; Tao, N.; Dergay, A.; Moy, P.; Fawell, S.; Davis, A.; Wilson, J.M.; Barsoum, J. Interferon-β Gene Therapy Inhibits Tumor Formation and Causes Regression of Established Tumors in Immune-Deficient Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 14411–14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studeny, M.; Marini, F.C.; Champlin, R.E.; Zompetta, C.; Fidler, I.J.; Andreeff, M. Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells as Vehicles for Interferon-β Delivery into Tumors. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3603–3608. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, S.; Caldwell, L.; Dietrich, M.; Samudio, I.; Spaeth, E.L.; Watson, K.; Shi, Y.; Abbruzzese, J.; Konopleva, M.; Andreeff, M.; et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Alone or Expressing Interferon-β Suppress Pancreatic Tumors in Vivo, an Effect Countered by Anti-Inflammatory Treatment. Cytotherapy 2010, 12, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetzkendorf, J.; Mueller, L.P.; Mueller, T.; Caysa, H.; Nerger, K.; Schmoll, H.J. Growth Inhibition of Colorectal Carcinoma by Lentiviral TRAIL-Transgenic Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Requires Their Substantial Intratumoral Presence. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loebinger, M.R.; Eddaoudi, A.; Davies, D.; Janes, S.M. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Delivery of TRAIL Can Eliminate Metastatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4134–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.R.; Fellabaum, C.; Jovicic, N.; Djonov, V.; Arsenijevic, N.; Volarevic, V. Molecular Mechanisms Responsible for Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Secretome. Cells 2019, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeppner, T.R.; Herz, J.; Görgens, A.; Schlechter, J.; Ludwig, A.-K.; Radtke, S.; de Miroschedji, K.; Horn, P.A.; Giebel, B.; Hermann, D.M. Extracellular Vesicles Improve Post-Stroke Neuroregeneration and Prevent Postischemic Immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Croce, C.M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Hua, X.; Yuanna, D.; Rukun, Z.; Junjun, M. Exosomal Mir-499a-5p Inhibits Endometrial Cancer Growth and Metastasis via Targeting Vav3. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 11255–11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Kolluri, K.K.; Gowers, K.H.; Janes, S.M. TRAIL Delivery by MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Is an Effective Anticancer Therapy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6, 1265291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalimuthu, S.; Gangadaran, P.; Li, X.; Oh, J.M.; Lee, H.W.; Baek, S.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, J.; Ahn, B.C. In Vivo Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles with Optical Imaging Reporter in Tumor Mice Model. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Z.; Han, Z.C.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Z. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Suppress Breast Cancer Progression by Inhibiting Angiogenesis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 30, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, L.; Coccè, V.; Bonomi, A.; Ami, D.; Ceccarelli, P.; Ciusani, E.; Viganò, L.; Locatelli, A.; Sisto, F.; Doglia, S.M.; et al. Paclitaxel Is Incorporated by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Released in Exosomes That Inhibit In Vitro Tumor Growth: A New Approach for Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2014, 192, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Liang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Therapy Resistance: From Biology to Clinical Opportunity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokati, A.; Rahnama, M.A.; Jalali, L.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Masoudifar, S.; Ahmadvand, M. Revolutionizing Cancer Treatment: Engineering Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Afzal, M.; Goyal, K.; Ganesan, S.; Kumari, M.; Sunitha, S.; Dash, A.; Saini, S.; Rana, M.; Gupta, G.; et al. MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Precision miRNA Delivery for Overcoming Cancer Therapy Resistance. Regen. Ther. 2025, 29, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimuthu, S.; Zhu, L.; Oh, J.M.; Gangadaran, P.; Lee, H.W.; Baek, S.H.; Rajendran, R.L.; Gopal, A.; Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, S.W.; et al. Migration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Tumor Xenograft Models and In Vitro Drug Delivery by Doxorubicin. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Nethi, S.K.; Rathi, S.; Layek, B.; Prabha, S. Engineered Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Targeting Solid Tumors: Therapeutic Potential beyond Regenerative Therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Song, Z. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment with Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Based Delivery Approach for Efficient Delivery of Anticancer Agents: An Updated Review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 232, 116725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoon, R.; Overdevest, N.; Saleh, A.H.; Keating, A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as Cancer Promoters. Oncogene 2024, 43, 3545–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, R. Role of MSC in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2020, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.Y. The Role of MSCs in the Tumor Microenvironment and Tumor Progression. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 3039–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prantl, L.; Muehlberg, F.; Navone, N.M.; Song, Y.-H.; Vykoukal, J.; Logothetis, C.J.; Alt, E.U. Adipose Tissue Derived Stem Cells Promote Prostate Tumor Growth. Prostate 2010, 70, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Xu, W.; Jiang, R.; Qian, H.; Chen, M.; Hu, J.; Cao, W.; Han, C.; Chen, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Bone Marrow Favor Tumor Cell Growth in Vivo. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2006, 80, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, P.; Huo, J.; Wu, H. Gastric Cancer-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prompt Gastric Cancer Progression through Secretion of Interleukin-8. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.T.; Dwyer, R.M.; Kelly, J.; Khan, S.; Murphy, J.M.; Curran, C.; Miller, N.; Hennessy, E.; Dockery, P.; Barry, F.P.; et al. Potential Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in the Breast Tumour Microenvironment: Stimulation of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 124, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Gumin, J.; Gao, F.; Figueroa, J.; Shinojima, N.; Takezaki, T.; Priebe, W.; Villarreal, D.; Kang, S.-G.; Joyce, C.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolated From Human Gliomas Increase Proliferation and Maintain Stemness of Glioma Stem Cells Through the IL-6/Gp130/STAT3 Pathway. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 2015, 33, 2400–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Han, Z.; Han, Z.C.; Li, Z. Proangiogenic Features of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Therapeutic Applications. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 1314709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, Y.; Ah-Pine, F.; Khettab, M.; Arcambal, A.; Begue, M.; Dutheil, F.; Gasque, P. The Dual Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer Pathophysiology: Pro-Tumorigenic Effects versus Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.J.; Chi, Y.; Yang, Z.X.; Li, Z.J.; Cui, J.J.; Song, B.Q.; Li, X.; Yang, S.G.; Han, Z.B.; Han, Z.C. Heterogeneity of Proangiogenic Features in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Bone Marrow, Adipose Tissue, Umbilical Cord, and Placenta. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, F.; Mei, H.; Wang, S.; Cheng, L. Human Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells Show More Efficient Angiogenesis Promotion on Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells than Umbilical Cord and Endometrium. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 7537589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, R.; Andrés, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Llonch, E.; Igea, A.; Gutierrez-Prat, N.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Nebreda, A.R. Regulation of Tumor Angiogenesis and Mesenchymal–Endothelial Transition by P38α through TGF-β and JNK Signaling. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.-C.; Zhang, H.-W.; Zhao, Q.-C.; Sun, L.; Yang, J.-J.; Hong, L.; Feng, F.; Cai, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Tumor Angiogenesis via the Action of Transforming Growth Factor Β1. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizárraga-Verdugo, E.; Avendaño-Félix, M.; Bermúdez, M.; Ramos-Payán, R.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.; Aguilar-Medina, M. Cancer Stem Cells and Its Role in Angiogenesis and Vasculogenic Mimicry in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Sun, K.; Zeng, R.; Yang, H. Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Exosomal miR-21-5p Enhances Angiogenesis in Endothelial Progenitor Cells to Promote Bone Repair via the NOTCH1/DLL4/VEGFA Signaling Pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brossa, A.; Fonsato, V.; Bussolati, B. Anti-Tumor Activity of Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 1872–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.T.; Pham, K.D.; Cao, H.T.Q.; Pham, P.V. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and the Angiogenic Regulatory Network with Potential Incorporation and Modification for Therapeutic Development. Biocell 2024, 48, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Manrreza, M.E. Participation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Regulation of Immune Response and Cancer Development. Bol. Méd. Hosp. Infant. México 2016, 73, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuiffo, B.G.; Karnoub, A.E. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Tumor Development. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2012, 6, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X.; Tian, C.; Zhao, M.; Sun, Y.; Huang, C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer Progression and Anticancer Therapeutic Resistance. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ren, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Rabson, A.B.; Roberts, A.I.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Employ IDO to Regulate Immunity in Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, A.H.; Gupta, A.; Spaeth, E.; Andreeff, M.; Marini, F. Concise Review: Dissecting a Discrepancy in the Literature: Do Mesenchymal Stem Cells Support or Suppress Tumor Growth? Stem Cells 2011, 29, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.A.; Meyer, J.R.; Greco, S.J.; Corcoran, K.E.; Bryan, M.; Rameshwar, P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect Breast Cancer Cells through Regulatory T Cells: Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived TGF-β. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5885–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balik, K.; Kaźmierski, Ł.; Maj, M.; Bajek, A. MSCs and CAFs Interactions in the Prostate and Bladder Cancer Microenvironment as the Potential Cause of Tumour Progression. Med. Res. J. 2023, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Oda, T.; Mori, N.; Kida, Y.S. Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Differentiate into Pancreatic Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Vitro. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 2268–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Fang, Q.; Liu, P.; Ma, D.; Cao, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Hu, T.; Wang, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells With Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Like Phenotype Stimulate SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis to Enhance the Growth and Invasion of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells Through Cell-to-Cell Communication. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 708513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, T.; Aoyagi, K.; Kawahara, A.; Murakami, N.; Isobe, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Kaku, H.; Fujita, F.; Akagi, Y. Evaluation of the Expression of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Stroma of Gastric Cancer Tissue. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2020, 4, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies of EMT in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Tamma, R.; Annese, T. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Historical Overview. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgayer, H.; Mahapatra, S.; Mishra, B.; Swain, B.; Saha, S.; Khanra, S.; Kumari, K.; Panda, V.K.; Malhotra, D.; Patil, N.S.; et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Cancer Metastasis: The Status Quo of Methods and Experimental Models. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ji, T.; Wu, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, J.; Lin, H.; Li, C.; Cai, X. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Tumor Growth via MAPK Pathway and Metastasis by Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Integrin α5 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mele, V.; Muraro, M.G.; Calabrese, D.; Pfaff, D.; Amatruda, N.; Amicarella, F.; Kvinlaug, B.; Bocelli-Tyndall, C.; Martin, I.; Resink, T.J.; et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Induce Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells through the Expression of Surface-Bound TGF-β. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 2583–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cargo | MSC Source | Tumor Indication | Model | Main Outcome | Key Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncolytic Viruses (OVs) | Ad-TD-nsIL12 | NA | recurrent high-grade glioma | Phase I clinical trial | Repeated administration was safe; showed signals of tumor growth control | [17] |

| Ad-p53 | NA | glioma | Phase I clinical trial | minimum toxicity; virus showed biological activity in tumor tissue | [18] | |

| GDEPT | cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine (CD/5-FC) | bone marrow-derived MSCs | glioblastoma | in vivo xenograft | tumor suppression; strong bystander effect; synergy with TMZ | [24] |

| herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) | stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) | brain metastasis model of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | in vivo metastasis model | strong bystander effect; tumor regression; prolonged survival; complete tumor regression in a subset of mice | [25] | |

| Therapeutic Proteins | IFN-β | bone marrow-derived MSCs | melanoma [39], pancreatic cancer [40] | in vivo xenograft | tumor growth inhibition; prolonged survival [39]; tumor suppression [40] | [39,40] |

| TRAIL | bone marrow-derived MSCs [41] | colorectal cancer (CRC) [41], lung metastases [42] | in vivo xenograft [41], in vivo metastasis model [42] | apoptosis induction in TRAIL-sensitive and TRAIL-resistant CRC cell lines [41]; metastatic reduction, complete elimination of metastatic disease in 38% of mice; no systemic toxicity [42] | [41,42] | |

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) | not specified | pancreatic cancer | in vivo xenograft | enhanced sensitivity to gemcitabine, lower toxicity | [35] |

| Extracellular Vehicles (EVs) | miR-499a-5p | mouse bone-marrow MSCs | endometrial cancer | in vivo xenograft | inhibited tumor growth and angiogenesis; reduced tumor volume, weight, and microvessel density; confirmed direct targeting of VAV3 | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Warzycha, M.; Oleksiuk, A.; Suska, O.; Kolanowski, T.J.; Rozwadowska, N. Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Oncology: Navigating Between Therapeutic Delivery and Tumor Promotion. Genes 2026, 17, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010108

Warzycha M, Oleksiuk A, Suska O, Kolanowski TJ, Rozwadowska N. Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Oncology: Navigating Between Therapeutic Delivery and Tumor Promotion. Genes. 2026; 17(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarzycha, Marta, Agnieszka Oleksiuk, Olga Suska, Tomasz Jan Kolanowski, and Natalia Rozwadowska. 2026. "Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Oncology: Navigating Between Therapeutic Delivery and Tumor Promotion" Genes 17, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010108

APA StyleWarzycha, M., Oleksiuk, A., Suska, O., Kolanowski, T. J., & Rozwadowska, N. (2026). Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Oncology: Navigating Between Therapeutic Delivery and Tumor Promotion. Genes, 17(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010108