1. Introduction

Inborn errors of immunity (IEIs), alternatively referred to as primary immunodeficiency disorders (PIDs), constitute a substantial and heterogeneous assemblage of genetic maladies characterized by compromised immune system development or functionality [

1,

2,

3]. As of the present, over 500 distinct IEIs have been documented, with phenotypic expressions ranging from severe combined immunodeficiency to more selective cellular or humoral deficiencies [

4]. These disorders are frequently recognized in early childhood due to recurrent, persistent, or atypical infections, autoimmune manifestations, or vulnerability to specific opportunistic pathogens [

5]. Nonetheless, diagnosis is often postponed, particularly in resource-constrained environments, as clinical manifestations may coincide with prevalent infectious diseases or hematological conditions [

6]. Significantly, individuals with IEIs are susceptible to life-threatening complications upon exposure to live-attenuated vaccines, such as Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), which is extensively utilized in tuberculosis-endemic areas. In these circumstances, heightened clinical awareness of IEIs is paramount [

7]. Disseminated infection following routine vaccination may constitute the first indication of an underlying genetic defect. Timely recognition and genetic confirmation enable personalized patient management, genetic counseling for families, and informed decisions regarding immunization schedules and infection control strategies [

8].

Among the heterogeneous spectrum of Inborn Errors of Immunity (IEIs), a distinct subset is characterized by Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Disease (MSMD) [

9]. These disorders are attributable to mutations in genes implicated in the interleukin-12/interferon-γ (IL-12/IFN-γ) signaling pathway, which is indispensable for host defense against intracellular mycobacteria [

10]. Individuals with MSMD exhibit heightened susceptibility to infections by weakly virulent mycobacteria, encompassing environmental strains and BCG vaccine strains, in addition to more pathogenic

Mycobacterium tuberculosis [

11]. Clinically, affected persons may manifest localized or disseminated BCG infections subsequent to neonatal vaccination, presenting with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, pulmonary lesions, and cutaneous involvement [

12]. These clinical presentations frequently resemble chronic granulomatous disease or recurrent bacterial abscesses, resulting in diagnostic ambiguity. In regions endemic for tuberculosis, where BCG vaccination is universally administered at birth, disseminated disease following vaccination strongly indicates an underlying immunodeficiency [

13]. Notwithstanding its clinical relevance, MSMD remains underrecognized, particularly in Central Asia, where epidemiological data are sparse and access to sophisticated genetic testing has only recently become accessible.

One of the genes implicated in MSMD is

TYK2, which encodes tyrosine kinase 2, a member of the Janus kinase family engaged in signaling for multiple cytokine receptors, including type I interferons, IL-12, and IL-23 [

14]. Deficiency of

TYK2, classified as Immunodeficiency-35 (IMD35), is an autosomal recessive disorder typified by increased vulnerability to mycobacterial and viral infections, recurrent respiratory disease, and in select cases elevated serum IgE levels [

15]. Laboratory investigations frequently reveal normal quantities of immune cells but impaired cellular signaling responses, distinguishing

TYK2 deficiency from combined immunodeficiencies characterized by lymphopenia. Several pathogenic variants in

TYK2 have been documented, ranging from frameshift and nonsense mutations to missense substitutions impacting kinase functionality [

16]. In certain patients, supplementary heterozygous variants in other immune-related genes, such as

MEFV, which is associated with familial Mediterranean fever, may function as genetic modifiers contributing to variable phenotypic severity. The incorporation of whole-exome sequencing (WES) and segregation analysis has consequently become essential in identifying causative mutations and elucidating genotype–phenotype correlations in intricate cases [

17].

Herein, we present the case of a Kazakh juvenile exhibiting recurrent disseminated BCG and tuberculosis infection, initially hypothesized to possess chronic granulomatous disease, but ultimately diagnosed with TYK2 deficiency through WES and corroborative Sanger sequencing. The proband harbored two rare variants in TYK2, encompassing a pathogenic frameshift mutation and a missense substitution of uncertain significance, in conjunction with a heterozygous MEFV duplication variant. The clinical manifestation encompassed persistent lymphadenitis, osteoarticular and cutaneous tuberculosis, recurrent abscess-like lesions, and elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels. The aim of this report is to elucidate the clinical trajectory, immunological characteristics, and genetic findings in this patient, thereby delineating the diagnostic pathway from clinical suspicion to molecular confirmation. This case underscores the significance of thorough immunological and genetic assessment in children with atypical or refractory mycobacterial infections, particularly in BCG-vaccinated cohorts. Furthermore, it contributes to the scant corpus of literature regarding TYK2 deficiency from Central Asia, offering novel insights into regional genetic epidemiology. By disseminating this case, we aspire to broaden the clinical spectrum of TYK2-related immunodeficiency, accentuate the diagnostic complexities in distinguishing it from other granulomatous disorders, and highlight the pivotal role of molecular diagnostics in steering patient management and vaccination strategies in endemic regions.

2. Case Presentation

The proband was a female child born in late 2016 in the Aktobe region of Kazakh-stan, the second child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents. Pregnancy, delivery, and early developmental milestones were unremarkable. She received all routine neonatal vaccinations, including BCG at birth, without early complications. No family history of recurrent infections, autoimmune disorders, or known immunodeficiency or active or treated pulmonary tuberculosis was reported.

Until approximately 2 years of age, her medical history was notable only for occasional upper respiratory infections. Shortly after turning 2 years old, she developed an enlarging, tender mass in the left axillary region ipsilateral to the neonatal BCG vaccination site, accompanied by persistent fever. Surgical drainage was performed, but wound healing was prolonged, with ongoing serous discharge. Over the following months, she experienced recurrent abscess-like lesions of the axilla and anterior chest wall, together with progressive cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. Histology repeatedly showed nonspecific granulomatous inflammation without evidence of malignancy.

During her third year of life, she developed additional lesions in the anterior thoracic wall and neck, along with prolonged fever and general malaise despite antimicrobial and antituberculosis therapy. Imaging revealed multiple cystic and infiltrative lymph node and soft tissue lesions, raising concern for chronic granulomatous or disseminated mycobacterial disease.

In her fourth year of life, she was evaluated by a hematologist, and primary immunodeficiency was suspected. A trial of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was administered, but new lymphadenopathy and soft tissue lesions continued to appear. She was referred to national specialized centers, where she was diagnosed with generalized BCG/tuberculosis infection and restarted on first-line antituberculosis therapy. Partial clinical improvement was observed, though disease activity persisted. During the same year, she also developed acute appendicitis requiring surgical intervention.

By age 4–5 years, the child remained underweight but clinically stable. Examination revealed multiple scars over the axillae, cervical region, and anterior chest wall corresponding to prior surgical drainages and lymph node resections. No hepatosplenomegaly or acute respiratory distress was noted. The combination of disseminated mycobacterial infection, recurrent abscess-like lesions, and failure to respond to prolonged antituberculosis therapy raised strong suspicion for an inborn error of immunity. This prompted referral for comprehensive immunologic evaluation and WES.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Patient and Setting

This study concerns a single female pediatric patient born in November 2016 and evaluated between 2020 and 2021 at regional and national centers in Kazakhstan, including the National Scientific Center of Phthisiopulmonology and the “University Medical Center” Corporate Fund (Astana, Kazakhstan). The referral indication was recurrent, refractory lymphadenitis with multisite involvement and a clinical suspicion of primary immunodeficiency. Clinical data were abstracted from standardized hospital charts and consultation notes, including perinatal history, immunization record, prior procedures, growth and development, and longitudinal infectious episodes. Guardians provided written informed consent for clinical genetic testing and publication of anonymized data.

3.2. Patient and Setting Clinical Assessment and Imaging

A structured clinical examination was performed by pediatric infectious disease and immunology specialists. The assessment included general status, growth parameters, dermatologic survey for scars and draining sinuses, peripheral lymph node stations, respiratory system, and abdominal palpation. Radiology was obtained according to clinical need. Chest radiography was performed in standard projection. Chest computed tomography was performed with thin-slice acquisition and mediastinal and lung reconstructions to characterize lymphadenopathy and parenchymal findings. Soft tissue ultrasound was used to delineate subcutaneous collections and nodal architecture. Imaging was reviewed by board-certified radiologists.

3.3. Microbiology and Histopathology

Surgical material from affected lymph nodes and soft tissues was processed locally according to institutional protocols. Routine stains and histopathology were performed to differentiate nonspecific granulomatous inflammation from suppurative processes or malignancy. Mycobacterial cultures from lymph node tissue were positive for M. tuberculosis complex. Strain-level differentiation between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG (e.g., PCR-based typing or pyrazinamidase testing) was not available at the treating institutions. Consequently, the diagnosis of BCG-related disease was established by national pediatric tuberculosis specialists based on the neonatal BCG vaccination history, chronic progressive lymphadenitis, and radiologic features typical of vaccine-derived infection. Bacteriologic evaluations and tuberculosis program diagnostics were conducted in accordance with national standards and pediatric TB guidelines.

3.4. Hematology, Inflammation, and Serum Immunochemistry

Complete blood counts and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were measured by automated analyzers with internal quality control, including a Sysmex XN-series hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). C-reactive protein and routine biochemistry were determined on clinical chemistry platforms, such as the Cobas c501 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Total immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) and complement components C3 and C4 were quantified by immunoturbidimetry or nephelometry according to manufacturer instructions, using reagent kits for BN II nephelometry (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Total IgE and allergen panels were measured by immunoassay on an automated chemiluminescent analyzer (e.g., Immulite 2000, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Viral serologies were performed by chemiluminescent or enzyme immunoassay per laboratory standard operating procedures, using commercial kits and platforms such as Architect i2000SR (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA).

3.5. Lymphocyte Immunophenotyping and Functional Assays

Peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets were quantified by flow cytometry using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD16, and CD56 with appropriate isotype controls, all purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Flow cytometric acquisition and analysis were performed on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Activated T cells were assessed with HLA-DR gating on CD3 positive lymphocytes. Absolute counts were derived from concurrent hematology indices.

Neutrophil oxidative burst was evaluated by a dihydrorhodamine-based assay (Phagoburst dihydrorhodamine 123 kit, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after phorbol ester stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and reported as the percentage of reactive cells in granulocyte and monocyte gates. Phagocytosis assays for granulocytes and monocytes were performed with opsonized particles using manufacturer protocols, employing a commercial phagocytosis assay (e.g., Phagotest kit, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). All assays followed internal controls and reference intervals validated by the clinical laboratory.

3.6. Whole-Exome Sequencing and Variant Calling

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral whole blood using a validated salt-out protocol, adapted from the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Whole-exome sequencing libraries were prepared with a clinical exome capture kit, the SureSelectXT Clinical Research Exome (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), following manufacturer recommendations for fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, and enrichment. Paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina platform, specifically the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Base calling and FASTQ generation used the instrument software pipeline, bcl2fastq v2.20 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Reads were aligned to GRCh38 using BWA-MEM (v0.7.17; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). Raw FASTQ files underwent quality control with FastQC (v0.12.1; Babraham Bioinformatics, Cambridge, UK). Post-processing included duplicate marking, base quality recalibration, and indel realignment following best practices using Picard tools (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA) and the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v4.4.0.0; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). Small variant discovery used a haplotype-based caller in gVCF mode (GATK HaplotypeCaller) with joint genotyping for family evaluation when parental samples were available.

3.7. Annotation, Filtering, and Clinical Interpretation

Variants were annotated with current releases of population and clinical databases and functional effect predictors, integrated through SnpEff (v5.2; Pablo Cingolani, Arlington, MA, USA) and Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (Ensembl, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK). Population filtering removed common variation using global and ancestry-specific allele frequencies from gnomAD, 1000 Genomes, and other public repositories. Candidate variants were prioritized if exonic or canonical splice, predicted protein-altering, and located in genes consistent with mycobacterial susceptibility syndromes and primary immunodeficiencies. Classification followed ACMG and AMP guidelines, integrating criteria such as very strong loss-of-function evidence in disease genes, rarity, segregation, phenotype specificity, and supportive literature. Copy-number and structural variants were not systematically assessed. Final variant interpretation was performed in a multidisciplinary conference with correlation to clinical phenotype, immunophenotyping, imaging, and histology.

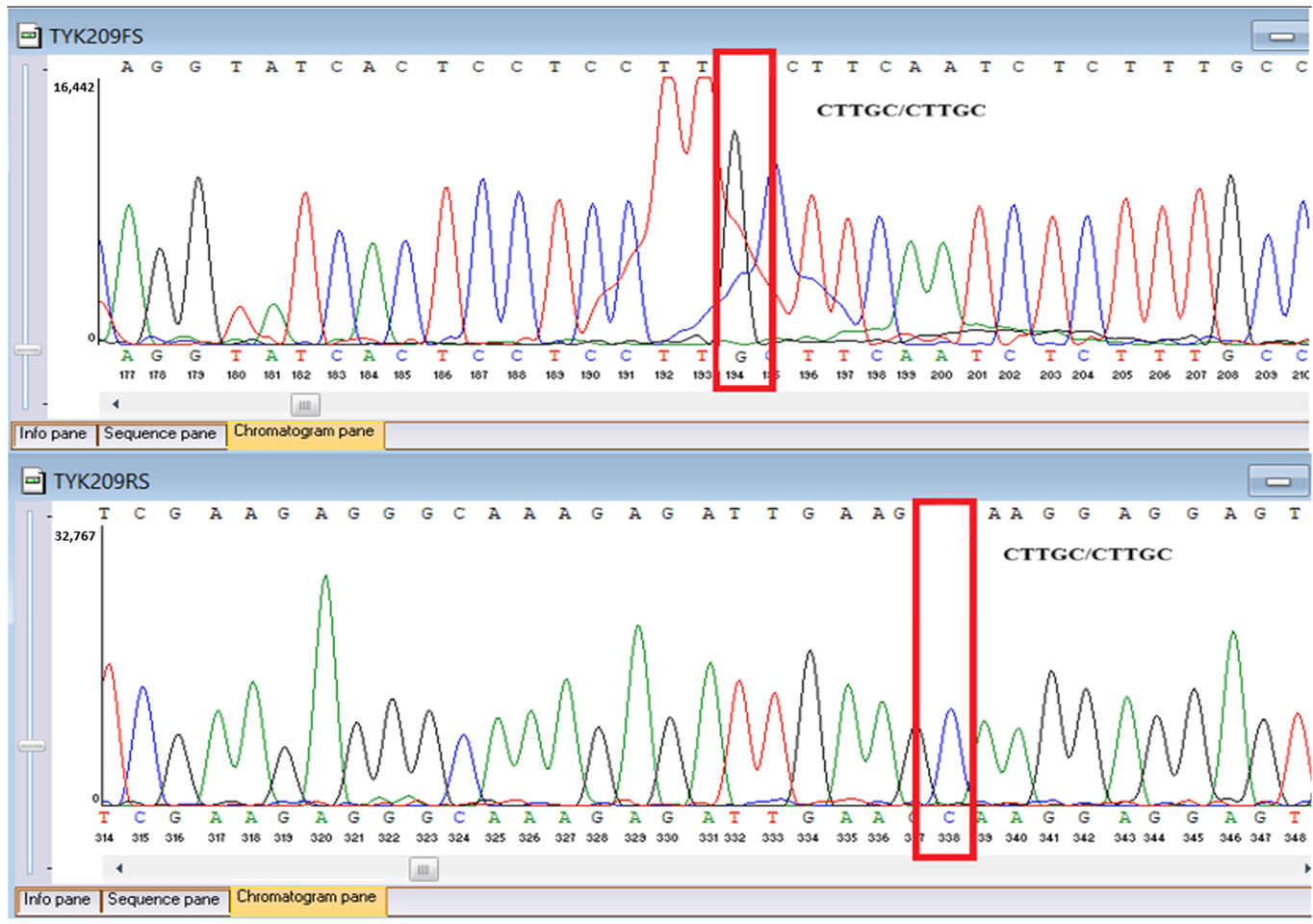

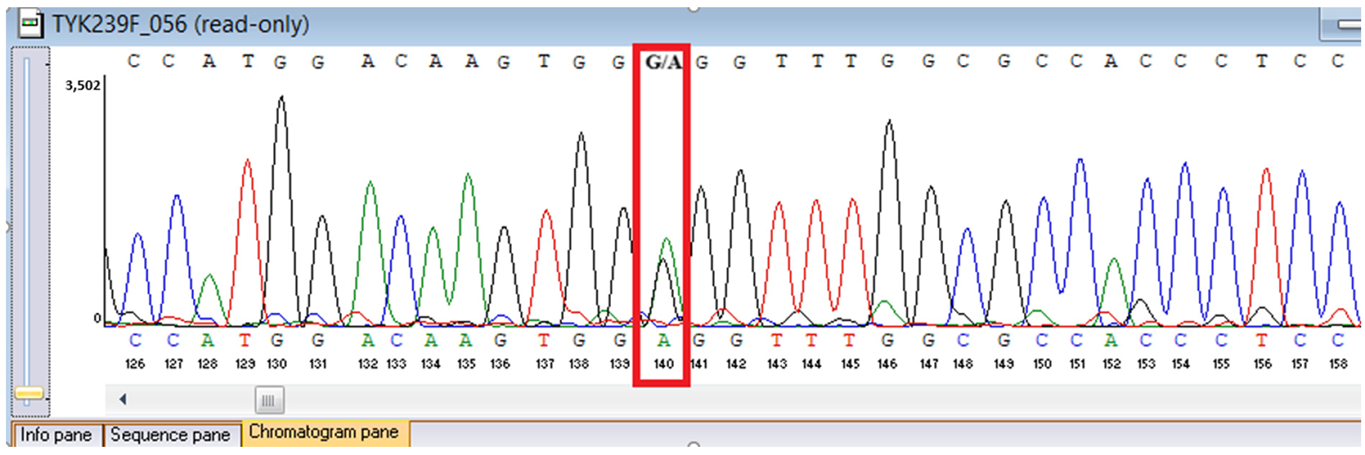

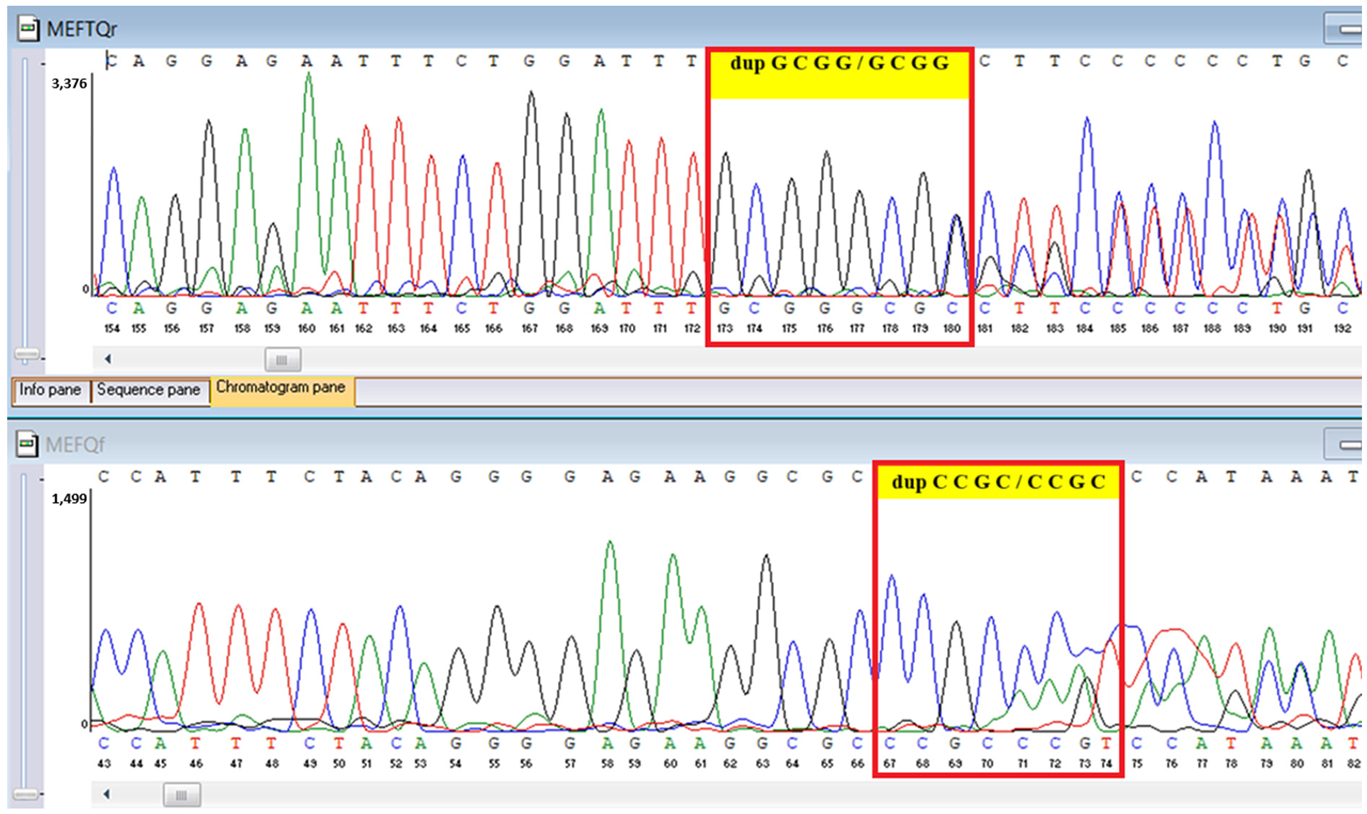

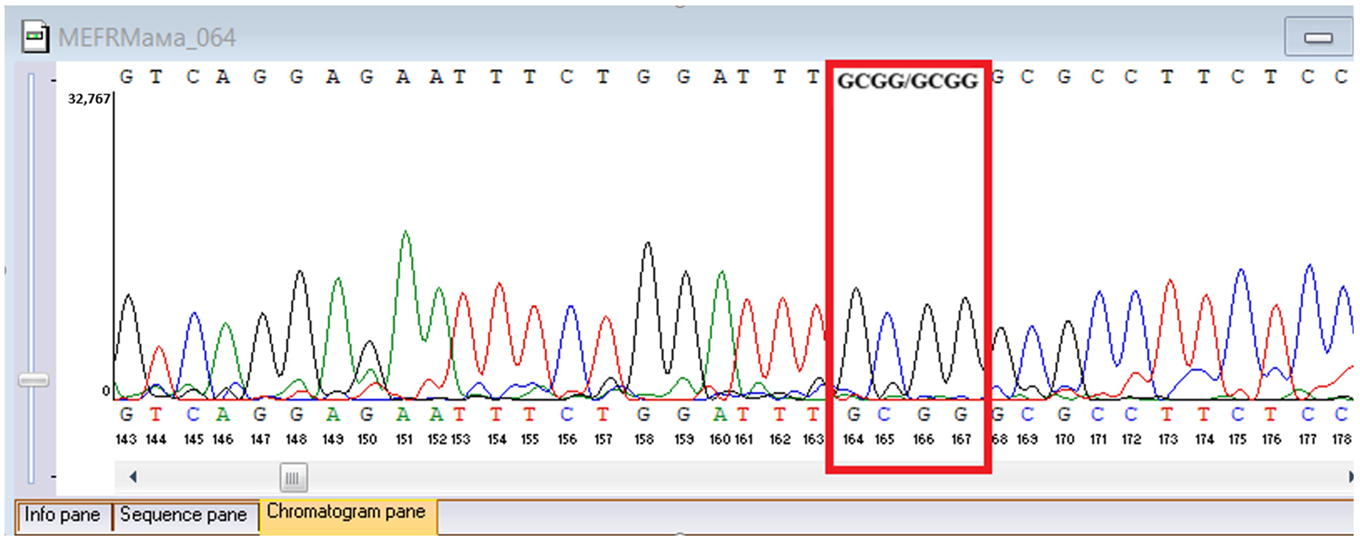

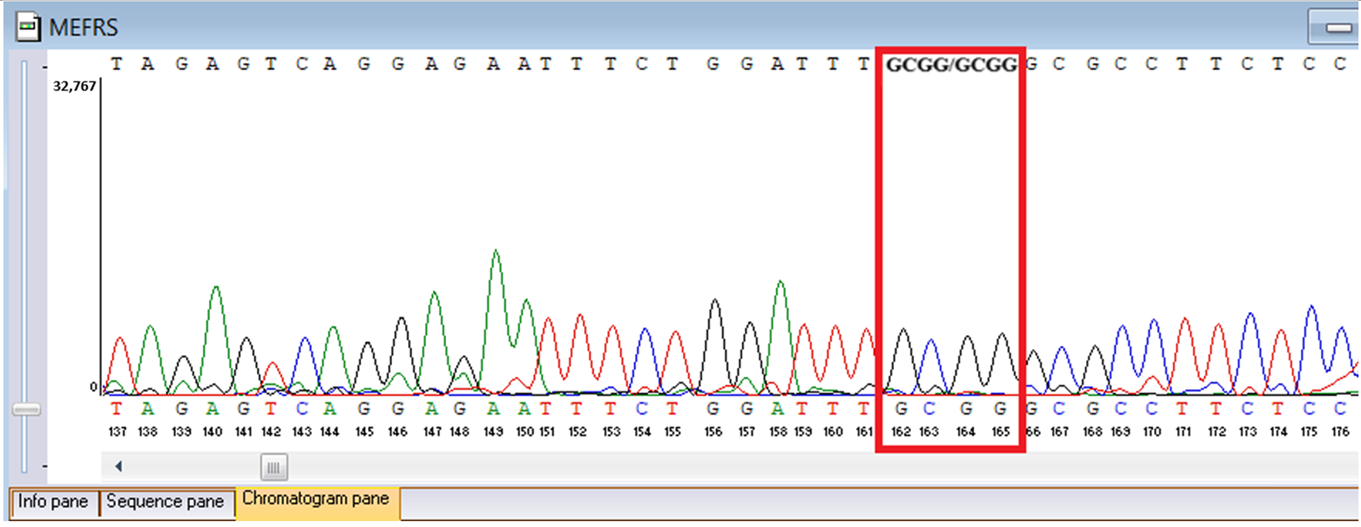

3.8. Sanger Confirmation and Segregation Analysis

Putative diagnostic variants were validated by bidirectional Sanger sequencing. Primers were designed to flank each locus by about 100 to 200 base pairs and synthesized at a national facility, the National Center for Biotechnology (Astana, Kazakhstan), using an ASM-800 DNA synthesizer (Biosset, Novosibirsk, Russia). PCR was performed under standard magnesium and cycling conditions with amplicon cleanup before capillary electrophoresis, using ExoSAP-IT (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) for PCR product purification. Capillary electrophoresis was conducted on an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Parental and sibling DNA was tested when available to assess inheritance (

Table 1).

3.9. Ethical Compliance

The protocol, consent documents, and data handling procedures were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the National Center for Biotechnology (Astana, Kazakhstan). The study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki and national regulations. Written informed consent for genetic testing and publication of de-identified clinical information and images was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian.

4. Results

At the initial evaluation around age 3.5 years, the patient exhibited anemia, reactive thrombocytosis, and markedly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), consistent with active systemic inflammation (

Table 2). By the following year (around age 4.5 years), hemoglobin and platelet counts had improved, and CRP had declined substantially, although the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) remained persistently elevated (

Table 2).

Serum studies in 2020 showed elevated IgG and a pronounced increase in total IgE, with IgA and IgM values slightly above or within reference intervals and normal C3 and C4 (

Table 3). At follow-up in 2021, IgG had normalized, IgE had declined significantly, and complement levels remained stable and within normal limits (

Table 3).

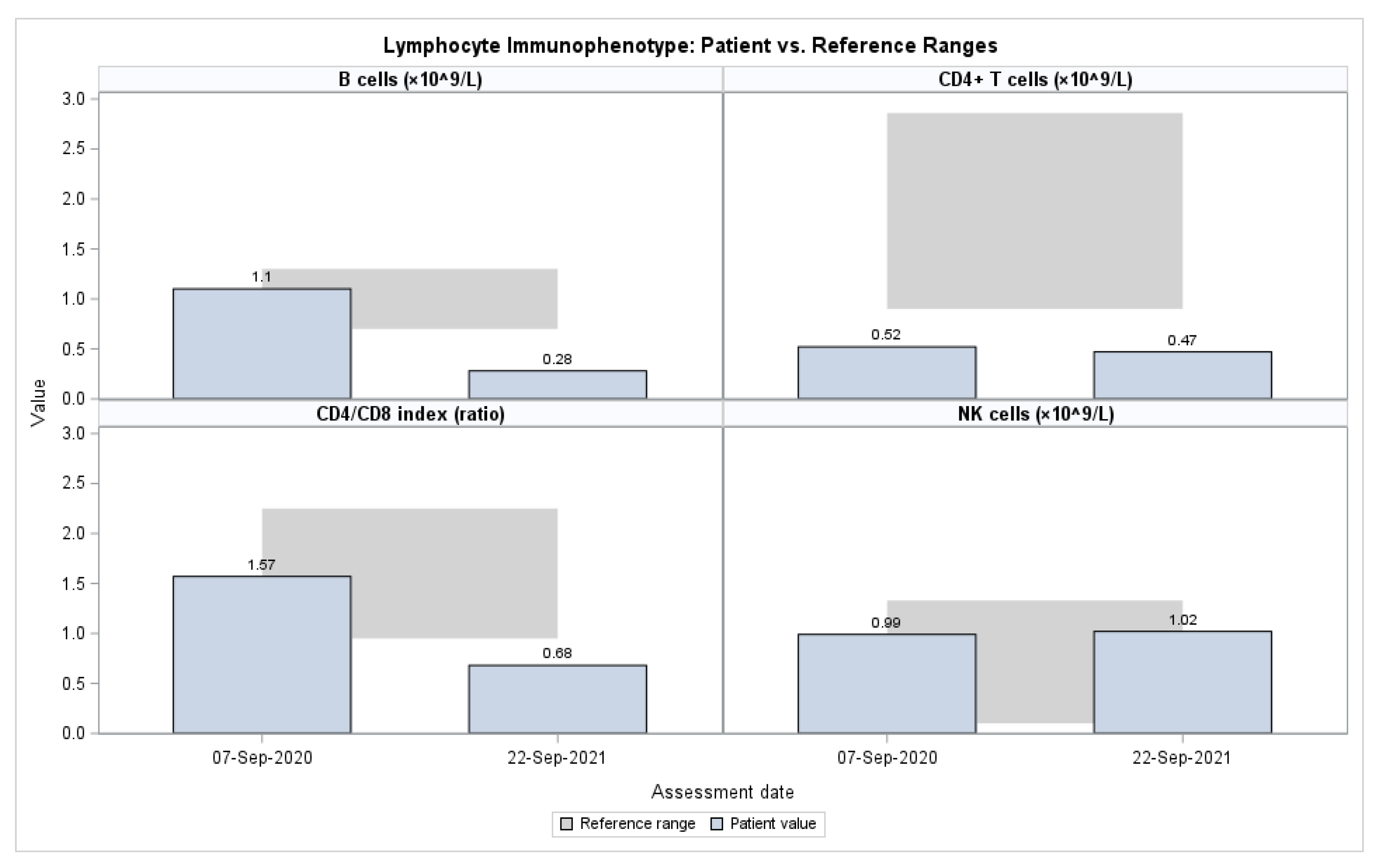

Flow cytometry performed in 2020 and 2021 demonstrated persistently reduced CD4+ T cells and a low CD4/CD8 ratio, accompanied by a progressive decline in CD19+ B cells. In contrast, NK-cell proportions were consistently elevated at both time points, and activated T cells (CD3+HLA-DR+) increased from 6.1% to 14.9% (

Table 4,

Figure 1). Functional testing in 2020 revealed preserved neutrophil and monocyte oxidative burst responses and intact phagocytic capacity, all within reference ranges, effectively excluding chronic granulomatous disease as a cause of the patient’s clinical presentation (

Table 5).

Serologic testing across 2020–2021 was negative for CMV, EBV, HSV-1/2, and hepatitis B. HIV testing was also negative. Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) and total IgE were markedly elevated in 2020 and declined by 2021. Both adult and pediatric Phadiatop allergen panels were negative. Biochemical indices, including glucose, urea, and hepatic enzymes, remained within normal limits throughout the evaluation period.

Cross-sectional imaging during 2020–2021 revealed persistent mediastinal and peripheral lymphadenopathy and anterior thoracic wall lesions, consistent with disseminated mycobacterial infection. Histopathology of excised lymph nodes demonstrated nonspecific granulomatous lymphadenitis without evidence of malignancy. Mycobacterial cultures from lymph node tissue grew M. tuberculosis complex. Strain-specific molecular typing was not available; therefore, the infection was classified as BCG-related tuberculosis by the national pediatric TB team based on the documented neonatal BCG vaccination, the clinical pattern of chronic progressive lymphadenitis, and characteristic radiologic findings. The child had received a single BCG dose in the neonatal period.

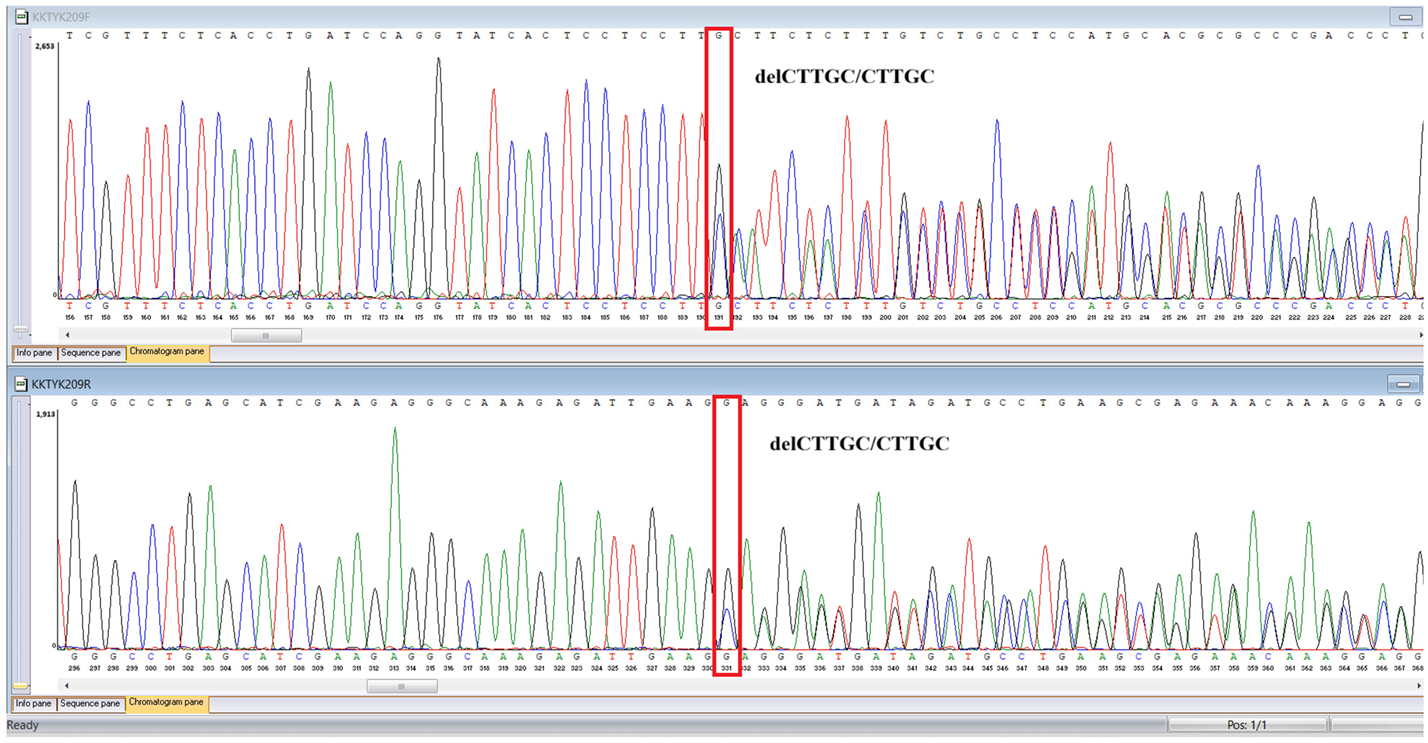

WES identified two rare

TYK2 variants: a pathogenic frameshift mutation,

c.209_212del (

p.Cys70Serfs21), and a missense variant,

c.2395G>A (

p.Gly799Arg), previously reported in a Chinese patient with

TYK2 deficiency and functionally characterized as deleterious, classified here as a variant of uncertain significance in our ACMG-based interpretation (

Table 6). A heterozygous MEFV duplication (

c.761_764dup;

p.Asn256Argfs70), classified as likely pathogenic, was also detected (

Table 6). In population databases,

p.Gly799Arg is absent or extremely rare, supporting its pathogenic potential; however, we classified it as a variant of uncertain significance according to ACMG criteria because no additional functional testing was performed in this patient.

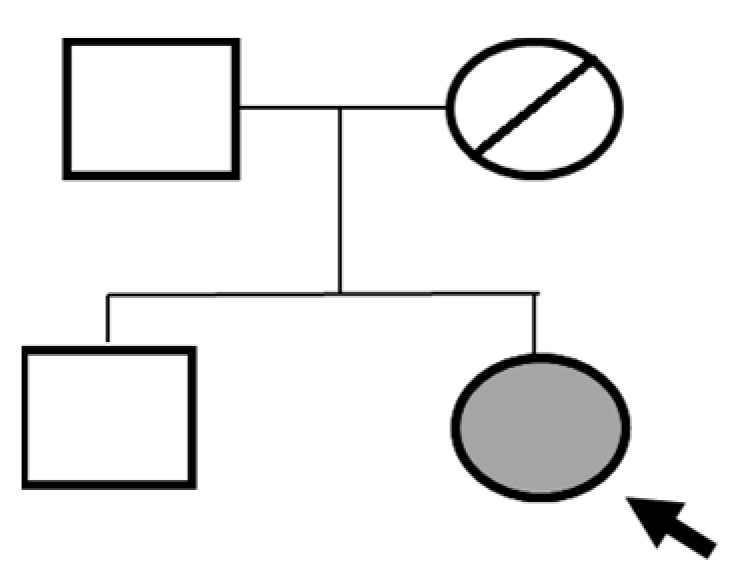

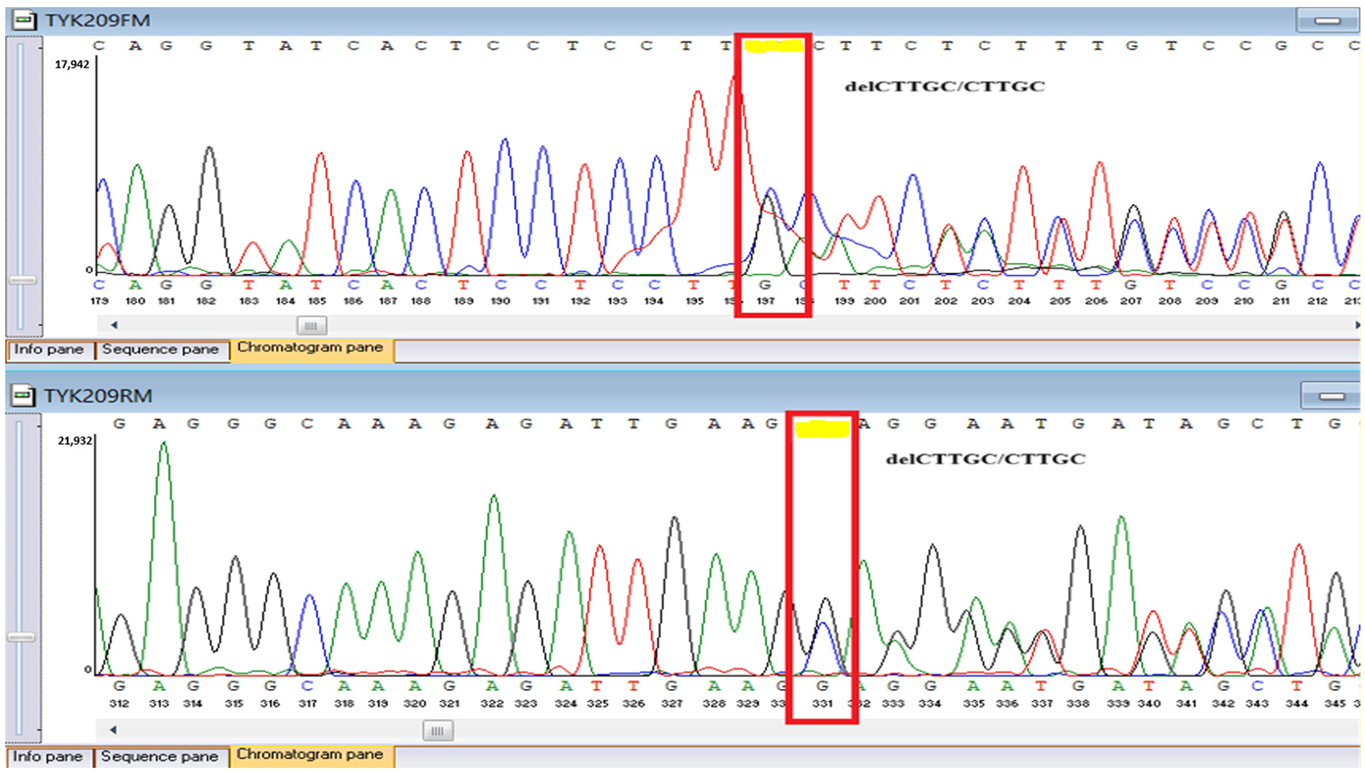

Sanger sequencing confirmed all three variants and clarified segregation within available family members (

Table 7,

Figure 2). The

TYK2 frameshift variant was present in the proband and mother, whereas the clinically and laboratory healthy brother carried only the wild-type allele. The missense

TYK2 variant was identified only in the proband. The

MEFV duplication was found in all three individuals tested. Neither the proband’s mother nor brother had a history of recurrent fevers, serositis, or other symptoms suggestive of

MEFV-associated autoinflammatory disease. Paternal DNA was unavailable; therefore, the allelic phase of the two

TYK2 variants (cis versus trans) cannot be experimentally confirmed, and this is acknowledged as a limitation of our study, although the overall genotype and phenotype are highly suggestive of autosomal recessive

TYK2 deficiency.

The proband’s brother, who is clinically and laboratorily healthy, did not carry the TYK2 c.209_212del frameshift variant. Paternal DNA was not available for analysis; phase of TYK2 variants is inferred but not experimentally confirmed.

5. Discussion

The clinical course of this patient illustrates the classical yet variable manifestations of

TYK2 deficiency, a form of Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Disease (MSMD) characterized by vulnerability to intracellular pathogens, particularly weakly virulent mycobacteria such as

Mycobacterium bovis BCG [

1,

6,

7]. Early-life dissemination of BCG following vaccination remains a hallmark presentation of IL-12/IFN-γ pathway defects [

14,

17]. From early childhood, our patient developed recurrent pulmonary and osteolytic infections, which were initially misattributed to complicated tuberculosis. Similar diagnostic delays have been documented in multiple cohorts due to overlapping clinical features with chronic granulomatous disease or severe tuberculosis [

4,

5,

11,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The present case underscores the need for heightened clinical suspicion of IEIs when BCG-related infections persist or recur despite adequate antimicrobial therapy.

Molecular confirmation through whole-exome sequencing identified two rare

TYK2 variants, comprising a truncating loss-of-function allele and the

p.Gly799Arg substitution, which has been previously reported in a Chinese patient and functionally validated as pathogenic in

TYK2 deficiency [

18], strongly supporting

TYK2-related MSMD in this child. However, because paternal DNA and

TYK2 cDNA cloning were unavailable, we cannot definitively determine whether the two variants are in trans, and we explicitly acknowledge this uncertainty regarding allelic phase as a limitation of our report. Functional studies in previous publications have shown that

TYK2 deficiency results in impaired IL-23–dependent induction of IFN-γ and defective downstream signaling of type I interferons [

18,

19]. No

TYK2 expression or cytokine-response assays were performed in our patient because of logistical constraints; therefore, we rely on previously published functional data for

p.Gly799Arg. Although the precise immunophenotype of

TYK2 deficiency varies, most affected individuals exhibit normal lymphocyte counts but aberrant cytokine responses, distinguishing this condition from combined immunodeficiencies [

4,

5,

17]. In our case, the immunological profile, featuring CD4+ lymphopenia and elevated IgE, corresponds to previously reported “hyper-IgE–like” phenotypes occasionally observed in

TYK2 deficiency [

1,

19].

The coexistence of an additional

MEFV variant in our proband may act as a genetic modifier contributing to the inflammatory phenotype, as similar oligogenic patterns have been observed in MSMD and other IEIs [

10,

11,

17]. The expanding use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has uncovered such digenic and modifier interactions, revealing a more complex genetic architecture underlying immune dysregulation [

11,

20].

MEFV-associated autoinflammatory disease (familial Mediterranean fever) typically follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, and single heterozygous carriers—such as the proband and her relatives—may remain clinically asymptomatic. In this context, we interpret the

MEFV frameshift variant as a potential modifier with possible future relevance for reproductive counseling, rather than as a primary driver of the current phenotype, and we are cautious not to overstate its contribution. The inflammatory markers observed in our patient were largely consistent with a high burden of disseminated mycobacterial infection, and we did not observe

MEFV-compatible autoinflammatory attacks in any family member. Segregation analysis in our family confirmed maternal carriage of the frameshift

TYK2 allele and absence of

TYK2 variants in the clinically healthy brother; paternal DNA was unavailable, so trans configuration cannot be formally proven, and this is explicitly acknowledged as a limitation of our study [

1,

11,

19]. Importantly, these findings further broaden the global

TYK2 mutational spectrum, adding to reports from East Asia, Europe, and the Middle East [

6,

7,

8,

17,

18,

19]. To our knowledge, this case represents one of the first genetically confirmed

TYK2 deficiencies in Central Asia, contributing unique epidemiological data to an underrepresented region [

15,

16,

21].

From a clinical perspective, this report reinforces the crucial role of early immunogenetic evaluation in children presenting with refractory or disseminated mycobacterial infections, particularly in BCG-vaccinated populations [

6,

11,

13]. Delayed diagnosis, as observed here, perpetuates unnecessary procedures and prolonged anti-tuberculosis therapy without addressing the underlying immune defect [

7,

17,

20]. Similar observations have been noted in the J Project registry, where diagnostic delays are common in low- and middle-income countries, including Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, due to limited genetic testing capacity [

15,

16,

21]. Earlier recognition of

TYK2 deficiency could have facilitated timely initiation of appropriate antimicrobial and immunomodulatory regimens, potentially reducing morbidity and preventing irreversible tissue damage. We acknowledge that strain-level confirmation of BCG versus

M. tuberculosis by PCR or drug susceptibility testing was not available, which limits the precision of etiologic attribution and is a common diagnostic constraint in resource-limited settings.

On a broader scale, our findings highlight the pressing need to strengthen IEI diagnostic infrastructure in Central Asia and similar resource-limited settings. Recent registry data from Kazakhstan identified over 200 confirmed IEI cases between 2009 and 2023, yet most lacked molecular diagnosis until recent years [

15]. These data echo earlier reports describing significant diagnostic barriers across the region, including lack of awareness, cost constraints, and absence of specialized immunology centers [

16,

21]. Collaborative initiatives such as the J Project have significantly expanded access to diagnostic and therapeutic support for IEI patients in 30 participating countries, emphasizing the transformative role of international cooperation in improving outcomes [

21].

In this context,

TYK2 deficiency serves as a paradigm for the integration of genomic screening into public health and vaccination policy. Routine BCG vaccination, widely practiced in tuberculosis-endemic countries, poses a substantial risk for infants with undiagnosed IEIs [

14,

17,

20]. Incorporating rapid genetic screening for key MSMD-associated genes (e.g.,

TYK2,

IL12RB1,

IFNGR1) in high-risk populations could mitigate these risks by enabling selective immunization strategies and targeted prophylaxis [

11,

13,

17]. The recently proposed international guidelines on MSMD management advocate for early molecular diagnosis, genetic counseling, and careful consideration of live-attenuated vaccine use in suspected IEI cases [

13,

17,

21].

Collectively, our report expands the clinical and molecular landscape of

TYK2 deficiency and provides region-specific evidence underscoring the necessity of genetic testing in patients with atypical mycobacterial disease. By aligning with global findings and regional epidemiological data, this study contributes to the broader effort to delineate genotype–phenotype correlations, refine diagnostic algorithms, and optimize care for rare primary immunodeficiencies [

1,

11,

13,

15,

17,

19,

20,

21,

22].