Comparative Analysis of Artemisia Plastomes, with Implications for Revealing Phylogenetic Incongruence and Evidence of Hybridization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

2.2. Plastome Assembly and Annotation

2.3. Comparison of Plastome Structures, Divergence Analyses, and SSR Search

2.4. Phylogenetic Inference

3. Results

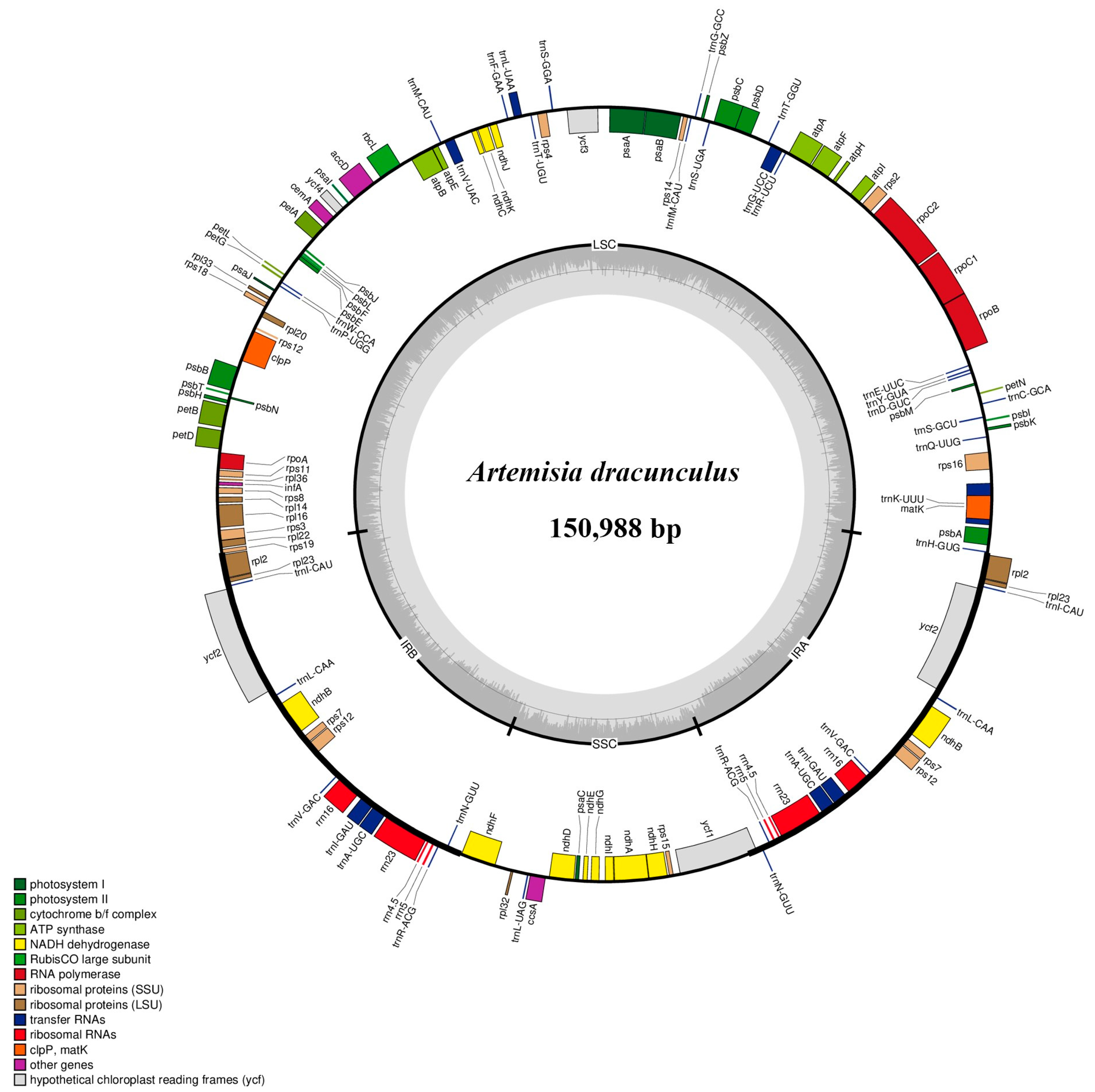

3.1. The General Features of Artemisia Plastomes

3.2. Sequence Divergence, SSR Comparison, and Barcode Identification

3.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDS | Protein-coding sequences |

| IGS | Intergenic spacer region |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer |

References

- Stull, G.W.; Pham, K.K.; Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. Deep reticulation: The long legacy of hybridization in vascular plant evolution. Plant J. 2023, 114, 743–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.X.; Chen, Y.Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, Q. Phylogenomic analyses revealed widely occurring hybridization events across Elsholtzieae (Lamiaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2024, 198, 108112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, J.; Besansky, N.; Hahn, M.W. How reticulated are species? BioEssays 2016, 38, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Zhou, T.; Han, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.L. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of six Rehmannia species. Genes 2017, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapli, P.; Yang, Z.; Telford, M.J. Phylogenetic tree building in the genomic age. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.R.; Humphries, C.J.; Gilbert, M.G. Artemisia Linnaeus. In Flora of China; Wu, Z.Y., Raven, P.H., Hong, D.Y., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2011; Volumes 20–21, pp. 676–737. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer, J.; Garnatje, T.; Korobkov, A.A.; Garnatje, T. Phylogenetic relationships of subgenus Dracunculus (genus Artemisia, Asteraceae) based on ribosomal and chloroplast DNA sequences. Taxon 2011, 60, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado-Ruiz, D.; Vallès, J.; Bayer, R.J.; Palazzesi, L.; Pellicer, J.; Lorenzo, I.P.; Maurin, O.; Françoso, E.; Roy, S.; Leitch, I.J.; et al. A phylogenomic approach to disentangling the evolution of the large and diverse daisy tribe Anthemideae (Asteraceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2024, 63, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.Y. The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normile, D. Nobel for antimalarial drug highlights East-West divide. Science 2015, 350, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallès, J. Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. In Advances in Botanical Research; Kader, J., Delseny, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Burlington, VT, USA, 2011; Volume 60, pp. 349–419. [Google Scholar]

- Shulz, L.M. Artemisia . In Flora of North America; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volumes 19–21, pp. 503–534. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, B.H.; Chen, C.; Wei, M.; Niu, G.H.; Zheng, J.Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Shen, J.H.; Vitales, D.; Vallès, J.; Verloove, F.; et al. Phylogenomics and morphological evolution of the mega-diverse genus Artemisia (Asteraceae: Anthemideae): Implications for its circumscription and infrageneric taxonomy. Am. J. Bot. 2023, 131, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.R. Artemisia L. In Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae; Ling, Y., Ling, Y.R., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1991; Volume 76, pp. 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer, J.; Saslis-Lagoudakis, C.H.; Carrió, E.; Ernst, M.; Garnatje, T.; Grace, O.M.; Gras, A.; Mumbrú, M.; Vallès, J.; Vitales, D.; et al. A phylogenetic road map to antimalarial Artemisia species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Vitales, D.; Hayat, M.Q.; Korobkov, A.A.; Garnatje, T.; Vallès, J. Phylogeny and biogeography of Artemisia subgenus Seriphidium (Asteraceae: Anthemideae). Taxon 2017, 66, 934–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C.R.; Baldwin, B.G. Asian origin and upslope migration of Hawaiian Artemisia (Compositae–Anthemideae). J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Q.; Huang, W.Q.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Xue, D.W.; Wu, Y.H. Comparative analysis of plastomes of Artemisia and insights into the infro-generic phylogenetic relationships within the genus. Genes 2025, 16, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendich, A.J. Circular chloroplast chromosomes: The grand illusion. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.D.; Xi, Z.X.; Mathews, S. Plastid phylogenomics and green plant phylogeny: Almost full circle but not quite there. BMC Biol. 2014, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.Y.; Liu, J.Q.; Hao, G.Q.; Zhang, L.; Mao, K.S.; Wang, X.J.; Zhang, D.; Ma, T.; Hu, Q.J.; Al-Shehbaz, I.; et al. Plastome phylogeny and early diversification of Brassicaceae. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitzendanner, M.A.; Soltis, P.S.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z.; Soltis, D.E. Plastome phylogenetics: 30 years of inferences into plant evolution. Adv. Bot. Res. 2018, 85, 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J.D. Comparative organization of chloroplast genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1985, 19, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Luo, Y.; Gan, L.; Ma, P.F.; Gao, L.M.; Yang, J.B.; Cai, J.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Fritsch, P.W.; Zhang, T.; et al. Plastid phylogenomic insights into relationships of all flowering plant families. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, S.E.; Smith, J.F.; Davidson, C.; Buerki, S. Phylogenetics and comparative plastome genomics of two of the largest genera of angiosperms, Piper and Peperomia (Piperaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 163, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, X.; Landis, J.B.; Sun, Y.X.; Sun, J.; Kuang, T.H.; Li, L.J.; Tiamiyu, B.B.; Deng, T.; Sung, H.; et al. Phylogenomic and comparative analyses of Rheum (Polygonaceae, Polygonoideae). J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 60, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.K.; Cai, Z.; Raubeson, L.A.; Daniell, H.; Depamphilis, C.W.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Müller, K.F.; Guisinger-Bellian, M.; Haberle, R.C.; Hansen, A.K.; et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19369–19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Wu, N.; Gao, X.F.; Zhang, L.B. Analysis of DNA sequences of six chloroplast and nuclear genes suggests incongruence, introgression, and incomplete lineage sorting in the evolution of Lespedeza (Fabaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 62, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Hu, Q.; Alshehbaz, I.A.; Luo, X.; Zeng, T.; Guo, X.Y.; Liu, J.Q. Species delimitation and interspecific relationships of the genus Orychophragmus (Brassicaceae) inferred from whole chloroplast genomes. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Wang, Z.F.; Luo, W.C.; Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Liu, J.Q.; Ren, G.P. Plastomes of Betulaceae and phylogenetic implications. J. Syst. Evol. 2019, 57, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.F.; Yuan, S.; Crowl, A.A.; Liang, Y.Y.; Shi, Y.; Chen, X.Y.; An, Q.Q.; Kang, M.; Manos, P.S.; Wang, B. Phylogenomic analyses highlight innovation and introgression in the continental radiations of Fagaceae across the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Y.; Wei, Z.Y.; Gu, Y.F.; Wang, T.; Liu, B.; Yan, Y.H. Chloroplast genome structure analysis of Equisetum unveils phylogenetic relationships to ferns and mutational hotspot region. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 15, 1328080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.B.; Ma, Z.Y.; Ren, C.; Hodel, R.G.J.; Sun, M.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, G.N.; Hong, D.Y.; Zimmer, E.A.; Wen, J. Capturing single-copy nuclear genes, organellar genomes, and nuclear ribosomal DNA from deep genome skimming data for plant phylogenetics: A case study in Vitaceae. J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 1124–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. Hybrid speciation. Nature 2007, 446, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paun, O.; Forest, F.; Fay, M.F.; Chase, M.W. Hybrid speciation in angiosperms: Parental divergence drives ploidy. New Phytol. 2008, 182, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenk, K.; Brede, N.; Streit, B. Introduction. Extent, processes and evolutionary impact of interspecific hybridization in animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 2805–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 561–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payseur, B.A.; Rieseberg, L.H. A genomic perspective on hybridization and speciation. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Briones, D.; Liston, A.; Tank, D.C. Phylogenomic analyses reveal a deep history of hybridization and polyploidy in the Neotropical genus Lachemilla (Rosaceae). New Phytol. 2018, 218, 1668–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, K.D.; Ahern, J.R.; Campbell, L.G.; Albert, L.P.; King, M.S. Patterns of hybridization in plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 12, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, L.T.; Olofsson, J.K.; Papadopulos, A.S.T.; Hibdige, S.G.S.; Hidalgo, O.; Leitch, I.J.; Baleeiro, P.C.; Ntshangase, S.; Barker, N.; Jobson, R.W. Hybridisation and chloroplast capture between distinct Themeda triandra lineages in Australia. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 5846–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.F.; Odago, W.O.; Jiang, H.; Yang, J.X.; Hu, G.W.; Wang, Q.F. Evolution of 101 Apocynaceae plastomes and phylogenetic implications. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2023, 180, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirie, M.D.; Humphreys, A.M.; Barker, N.P.; Linder, H.P. Reticulation, data combination, and inferring evolutionary history: An example from Danthonioideae (Poaceae). Syst. Biol. 2009, 58, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kuppler, A.L.M.; Fagúndez, J.; Bellstedt, D.U.; Oliver, E.G.H.; Léon, J.; Pirie, M.D. Testing reticulate versus coalescent origins of Erica lusitanica using a species phylogeny of the northern heathers (Ericeae, Ericaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 88, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunert, A.; Heubl, G. Against all odds: Reconstructing the evolutionary history of Scrophularia (Scrophulariaceae) despite high levels of incongruence and reticulate evolution. Org. Divers. Evol. 2017, 17, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; de Pamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G. Novoplasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucl. Acids. Res. 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, X.J.; Moore, M.J.; Li, D.Z.; Yi, T.S. PGA: A software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.L.; Cheung, M.L.; Sturrock, S.L.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW(OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucl. Acids. Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiryousefi, A.; Hyvönen, J.; Poczai, P. IRscope: An online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3030–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Muscle: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl. Acids. Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.; Thiel, T.; Münch, T.; Scholz, U.; Mascher, M. Misa-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2583–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Hohna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Evol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, D.M.; Bull, J.J. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 1993, 42, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree v1. 3.1. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Jin, G.Z.; Li, W.J.; Song, F.; Yang, L.; Wen, Z.B.; Feng, Y. Comparative analysis of complete Artemisia subgenus Seriphidium (Asteraceae: Anthemideae) chloroplast genomes: Insights into structural divergence and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maréchal, A.; Brisson, N. Recombination and the maintenance of plant organelle genome stability. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jun, M.; Park, S.; Park, S. Lineage-Specific Variation in IR Boundary Shift Events, Inversions, and Substitution Rates among Caprifoliaceae s.l. (Dipsacales) Plastomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, F.; Wu, X.; Li, T.; Jia, M.; Liu, X.; Liao, L. The complete chloroplast genome of Stauntonia chinensis and compared analysis revealed adaptive evolution of subfamily Lardizabaloideae species in China. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Hu, Y.; Lv, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Hu, Z. Chloroplast genomes of five Oedogonium species: Genome structure, phylogenetic analysis and adaptive evolution. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.E.; Fay, M.F.; Cronk, Q.C.B.; Bowman, D.; Chase, M.W. A phylogenetic analysis of Rhamnaceae using rbcL and trnL-F plastid DNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2000, 87, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufford, L.; Moody, M.L.; Soltis, D.E. A phylogenetic analysis of Hydrangeaceae based on sequences of the plastid gene matK and their combination with rbcL and morphological data. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 162, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.A.; Chase, M.W.; SotoArenas, M.A.; Ingrouille, M. Phylogenetics of Cranichideae with emphasis on Spiranthinae (Orchidaceae, Orchidoideae): Evidence from plastid and nuclear DNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.B.; Lim, C.E.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, H.J.; Mun, J.H. Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of Artemisia (Asteraceae) in East Asia: Insights into evolutionary divergence and phylogenomic implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 21, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.E. Taxonomic notes on Artemisia waltonii (Asteraceae, Anthemideae), with reduction of A. kangmarensis and A. conaensis to the synonymy of its type variety. Phytotaxa 2020, 450, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.E. Artemisia flaccida (Asteraceae, Anthemideae) is merged with A. fulgens, with transfer of A. flaccida var. meiguensis to A. fulgens. Phytotaxa 2021, 514, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.E. Clarification of morphological characters and geographical distribution of Artemisia neosinensis (Asteraceae, Anthemideae), a strikingly misunderstood species from China. Phytotaxa 2022, 544, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.Y.; Xin, G.L.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhao, D.M. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Dalbergia hainanensis (Leguminosae), a vulnerably endangered legume endemic to China. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2018, 11, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuza, L.; Gastineau, R.; Sielska, A. The complete chloroplast genome of Secale sylvestre (Poaceae: Triticeae). J. Appl. Genet. 2022, 63, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Zhou, C.; Ahmad, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.H.; Liu, Z.J.; Peng, D.H. Comparative phylogenetic analysis for aerides (Aeridinae, orchidaceae) based on six complete plastid genomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.; Peakall, R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): Technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Geng, F.D.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, D.Q.; Gao, F.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.H.; Kang, J.Q.; Ren, Y. Divergence in the Aquilegia ecalcarata complex is correlated with geography and climate oscillations: Evidence from plastid genome data. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 5796–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.S.; Sun, Y.Q.; Jin, Y.; Gao, Q.; Hu, X.G.; Gao, F.L.; Yang, X.L.; Zhu, J.J.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Mao, J.F. Development of high transferability cpSSR markers for individual identification and genetic investigation in Cupressaceae species. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 4967–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, W.P. Gene trees in species trees. Syst. Biol. 1997, 46, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, D.A.; Iyer, V.N.; Moses, A.M.; Eisen, M.B. Wide spread discordance of gene trees with species tree in Drosophila: Evidence for incomplete lineage sorting. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellstrand, N.C. Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants? Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pease, J.B.; Haak, D.C.; Hahn, M.W.; Moyle, L.C. Phylogenomics reveals three sources of adaptive variation during a rapid radiation. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.X.; Ragan, M.A. Next-generation phylogenomics. Biol. Direct. 2013, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E.M.; Lemmon, A.R. High-throughput genomic data in systematics and phylogenetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwickl, D.J.; Stein, J.C.; Wing, R.A.; Ware, D.; Sanderson, M.J. Disentangling methodological and biological sources of gene tree discordance on Oryza (Poaceae) chromosome 3. Syst. Biol. 2014, 63, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.J.; Hegarty, M.J.; Hiscock, S.J.; Brennan, A.C. Homoploid hybrid speciation in action. Taxon 2010, 59, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, E.D.; Mudge, J.; Van Buren, R.; Andersen, W.R.; Sanderson, S.C.; Babbel, D.G. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (RAPD) of Artemisia subgenus Tridentatae species and hybrids. Great Basin Nat. 1998, 58, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, H.D.; Shultz, L.M.; McArthur, E.D. Studies of a new hybrid taxon in the Artemisia tridentata (Asteraceae: Anthemideae) complex. West. N. Am. Nat. 2013, 73, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.M.; Chen, S.M.; Lu, A.M.; Chen, F.D.; Tang, F.P.; Guan, Z.Y.; Teng, N.J. Production and characterisation of the intergeneric hybrids between Dendranthema morifolium and Artemisia vulgaris exhibiting enhanced resistance to chrysanthemum aphid (Macrosiphoniella sanbourni). Planta 2010, 231, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.M.; Chen, S.M.; Chang, Q.S.; Wang, H.B.; Chen, F.D. The chrysanthemum× Artemisia vulgaris intergeneric hybrid has better rooting ability and higher resistance to alternaria leaf spot than its chrysanthemum parent. Sci. Hort. 2012, 134, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelser, B.P.; Kennedy, A.H.; Tepe, E.J.; Shidler, J.B.; Nordenstam, B.; Kadereit, J.W.; Watson, L.E. Patterns and causes of incongruence between plastid and nuclear Senecioneae (Asteraceae) phylogenies. Am. J. Bot. 2010, 97, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, D.; Yu, Y.; Hahn, M.W.; Nakhleh, L. Reticulate evolutionary history and extensive introgression in mosquito species revealed by phylogenetic network analysis. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 2361–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxon | Genbank Accession Number | Length (bp) | GC Content | LSC Size (bp) | IR Size (bp) | SSC Size (bp) | Protein Encoding Gene | tRNA | rRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. dracunculus | PQ850015 | 150,988 | 0.375 | 82,773 | 24,959 | 18,297 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. dubia var. dubia 1 | PQ850014 | 151,013 | 0.375 | 82,776 | 24,959 | 18,319 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. dubia var. dubia 2 | PQ850013 | 151,024 | 0.375 | 82,817 | 24,959 | 18,289 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. dubia var. subdigitata | PQ850012 | 151,032 | 0.375 | 82,794 | 24,959 | 18,320 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. giraldii var. giraldii | PQ850011 | 151,045 | 0.375 | 82,802 | 24,959 | 18,325 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. giraldii var. longipedunculata1 | PQ850010 | 150,662 | 0.375 | 82,542 | 24,926 | 18,268 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. giraldii var. longipedunculata2 | PQ850009 | 151,009 | 0.375 | 82,783 | 24,959 | 18,308 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. nanschanica 1 | PQ850008 | 151,008 | 0.375 | 82,777 | 24,959 | 18,313 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. nanschanica 2 | PQ850007 | 150,655 | 0.375 | 82,535 | 24,926 | 18,268 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. nanschanica 3 | PQ850006 | 151,031 | 0.375 | 82,804 | 24,959 | 18,309 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. tridactyla | PQ850005 | 150,654 | 0.375 | 82,556 | 24,927 | 18,244 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. waltonii | PQ850004 | 151,042 | 0.375 | 82,814 | 24,959 | 18,310 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. desertorum var. desertorum 1 | PQ850003 | 151,014 | 0.375 | 82,812 | 24,959 | 18,284 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. desertorum var. desertorum 2 | PQ850002 | 151,102 | 0.375 | 82,878 | 24,959 | 18,306 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. pratti | PQ850001 | 151,052 | 0.375 | 82,847 | 24,959 | 18,287 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. desertorum var. tongolensis | PQ850019 | 151,061 | 0.375 | 82,855 | 24,959 | 18,288 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. desertorum var. desertorum 3 | PQ850018 | 151,125 | 0.375 | 82,900 | 24,963 | 18,299 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. eriopoda 1 | PQ850017 | 151,064 | 0.375 | 82,853 | 24,959 | 18,293 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

| A. eriopoda 2 | PQ850016 | 151,105 | 0.375 | 82,871 | 24,963 | 18,308 | 87 | 37 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, X.; Bai, Y.; Ruan, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, S.; Xue, D.; Wu, Y. Comparative Analysis of Artemisia Plastomes, with Implications for Revealing Phylogenetic Incongruence and Evidence of Hybridization. Genes 2025, 16, 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101145

Guo X, Bai Y, Ruan J, Jin X, Wang S, Xue D, Wu Y. Comparative Analysis of Artemisia Plastomes, with Implications for Revealing Phylogenetic Incongruence and Evidence of Hybridization. Genes. 2025; 16(10):1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101145

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Xinqiang, Yonghe Bai, Jing Ruan, Xin Jin, Shang Wang, Dawei Xue, and Yuhuan Wu. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Artemisia Plastomes, with Implications for Revealing Phylogenetic Incongruence and Evidence of Hybridization" Genes 16, no. 10: 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101145

APA StyleGuo, X., Bai, Y., Ruan, J., Jin, X., Wang, S., Xue, D., & Wu, Y. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Artemisia Plastomes, with Implications for Revealing Phylogenetic Incongruence and Evidence of Hybridization. Genes, 16(10), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101145