Thaumatin-Like Protein (TLP) Gene Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Exploration and Expression Analysis during Germination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

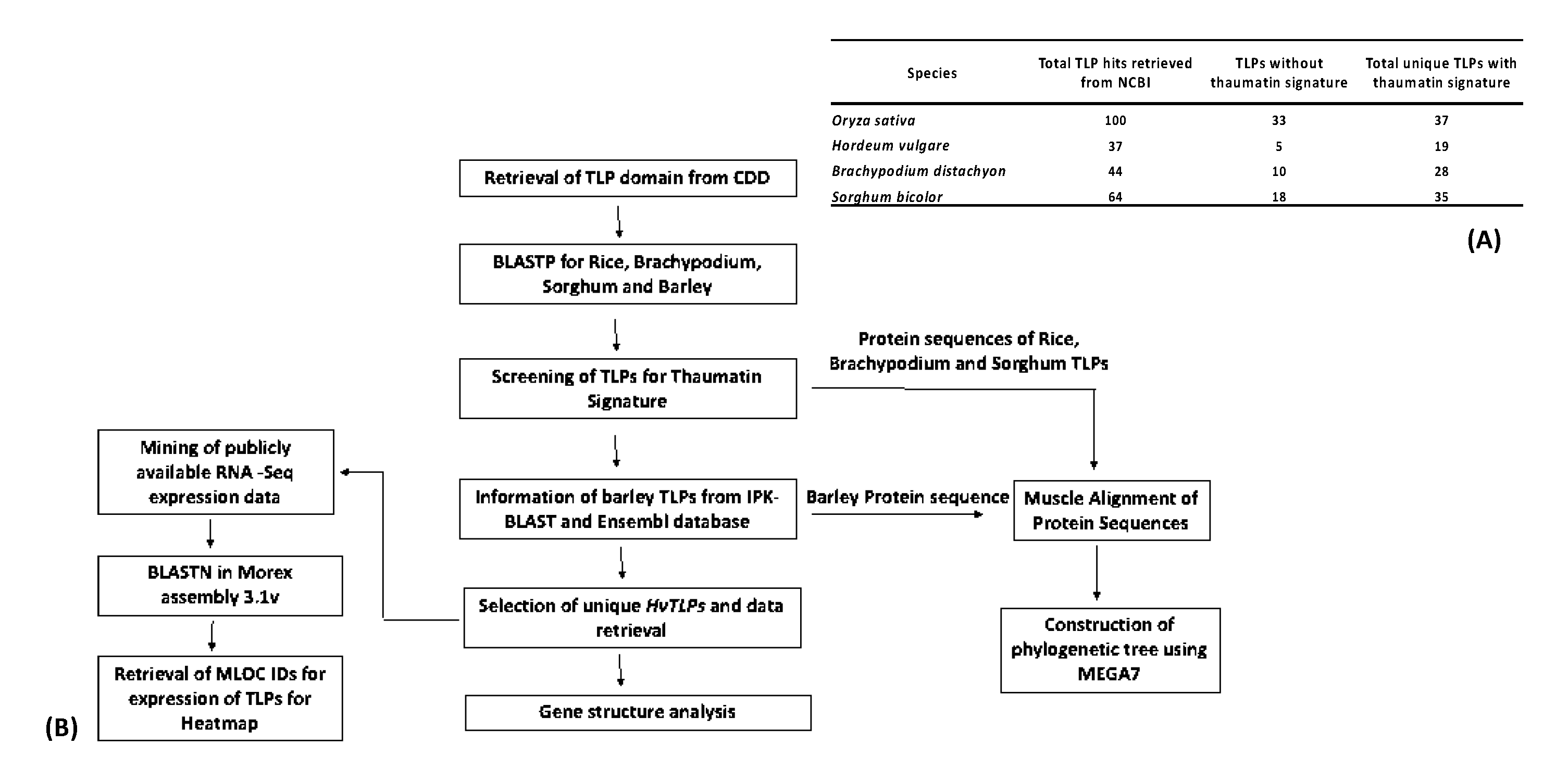

2.1. Sequence Retrieval and Identification of Thaumatin-Like Proteins in Cereals

2.2. Characteristics of TLPs and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Chromosomal Location, Exon/Intron Structure and Alternative Splice Variants Analysis of Barley TLP Genes

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis of Novel Barley TLPs in Different Tissues of a Barley Variety, Morex

2.5. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.6. Total RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

2.7. RT-PCR Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of TLP Gene Family in Cereals

3.2. HvTLP Protein Feature Analysis

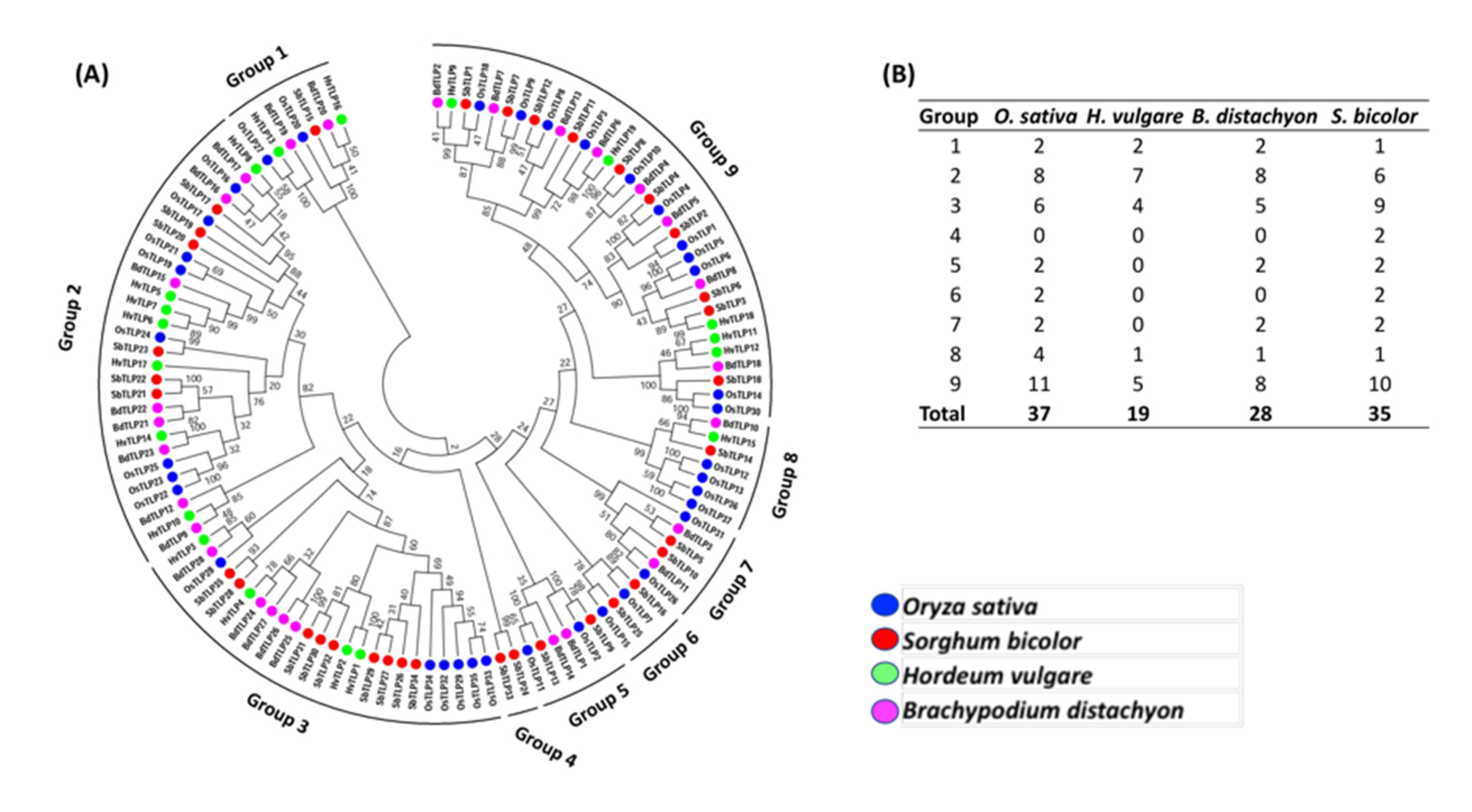

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationship of TLP Genes in Barley, Rice, Brachypodium and Sorghum

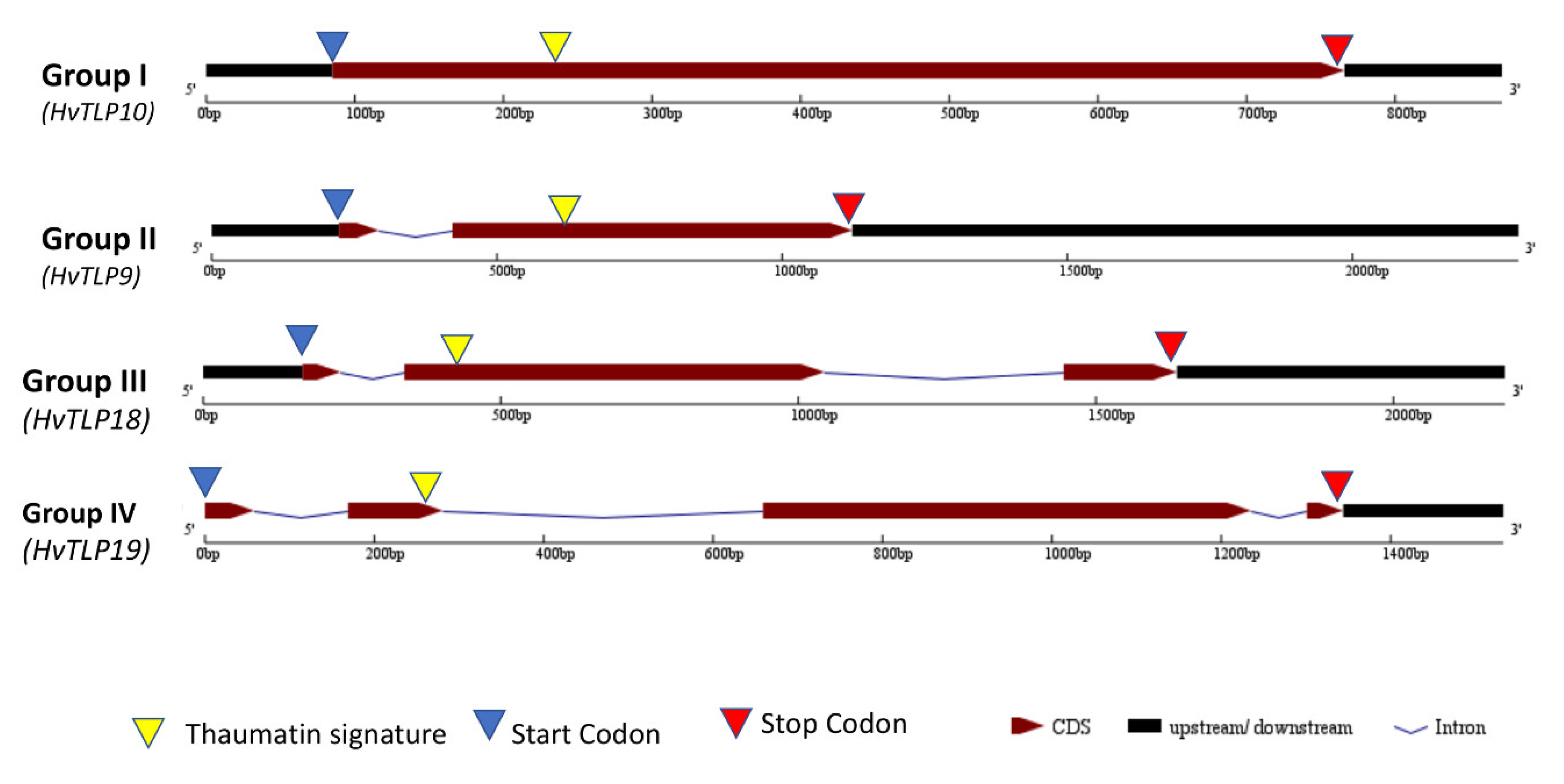

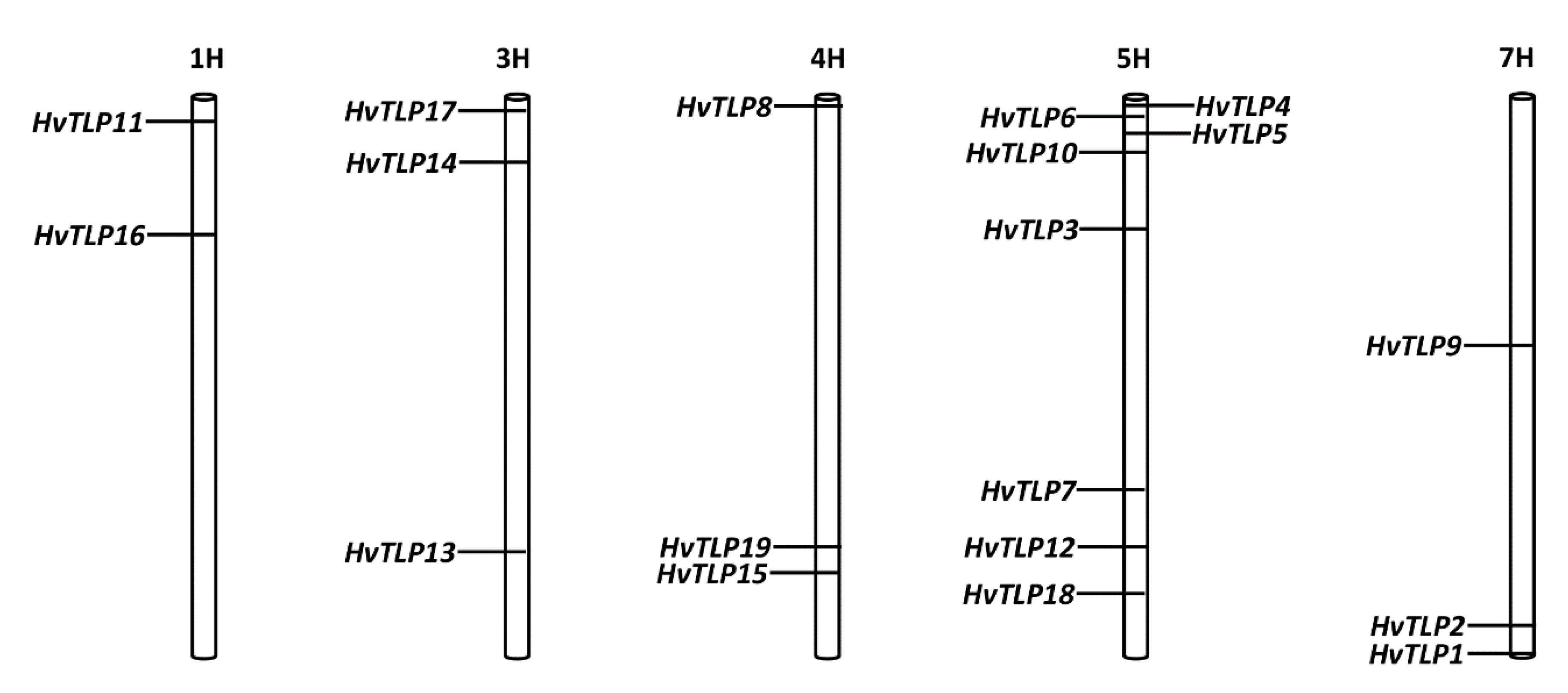

3.4. Gene Structure Analysis and Identification of Thaumatin Signature in Barley TLPs

3.5. Alternative Splicing in HvTLPs

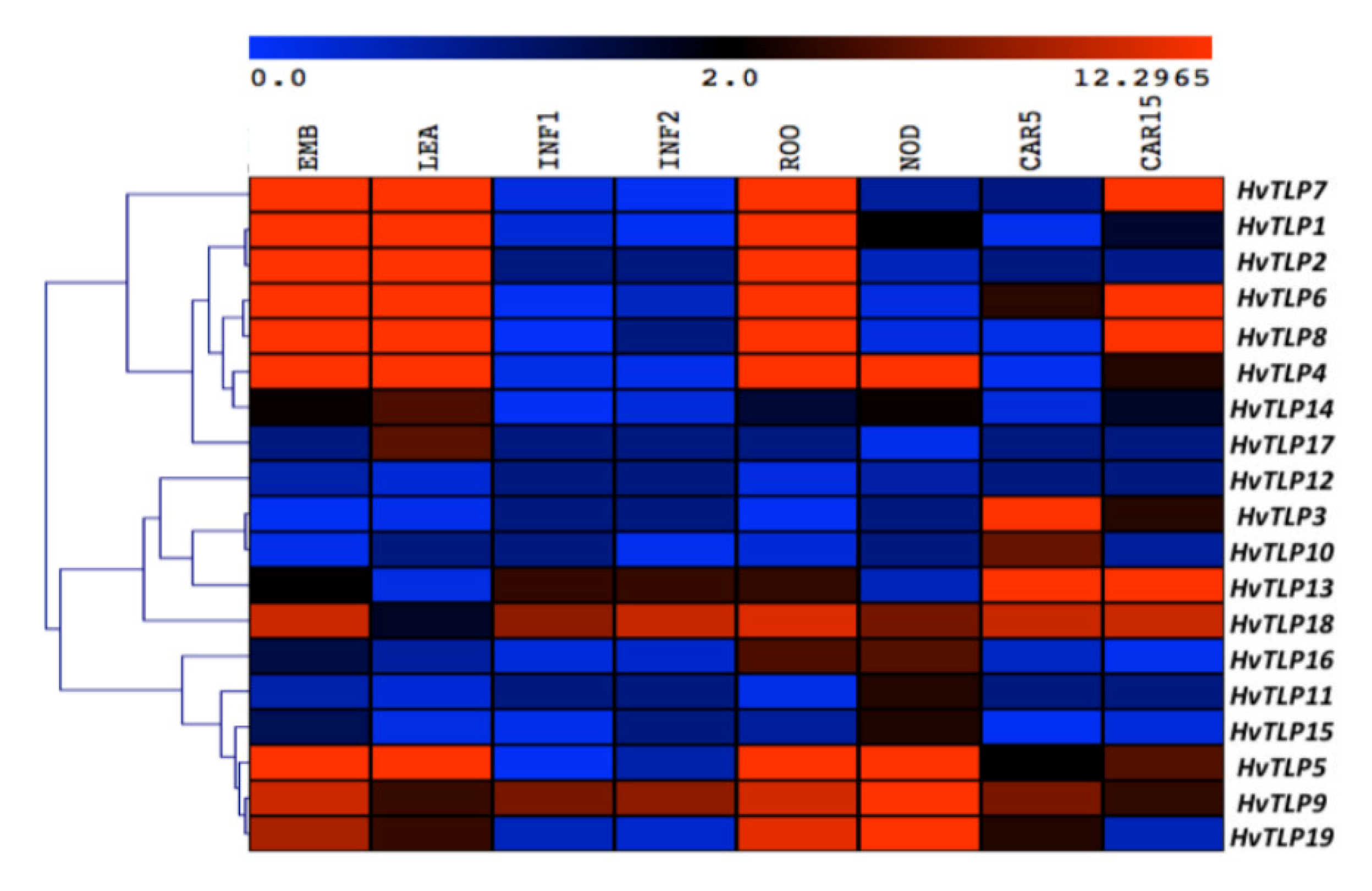

3.6. Spatiotemporal Expression Pattern of HvTLPs

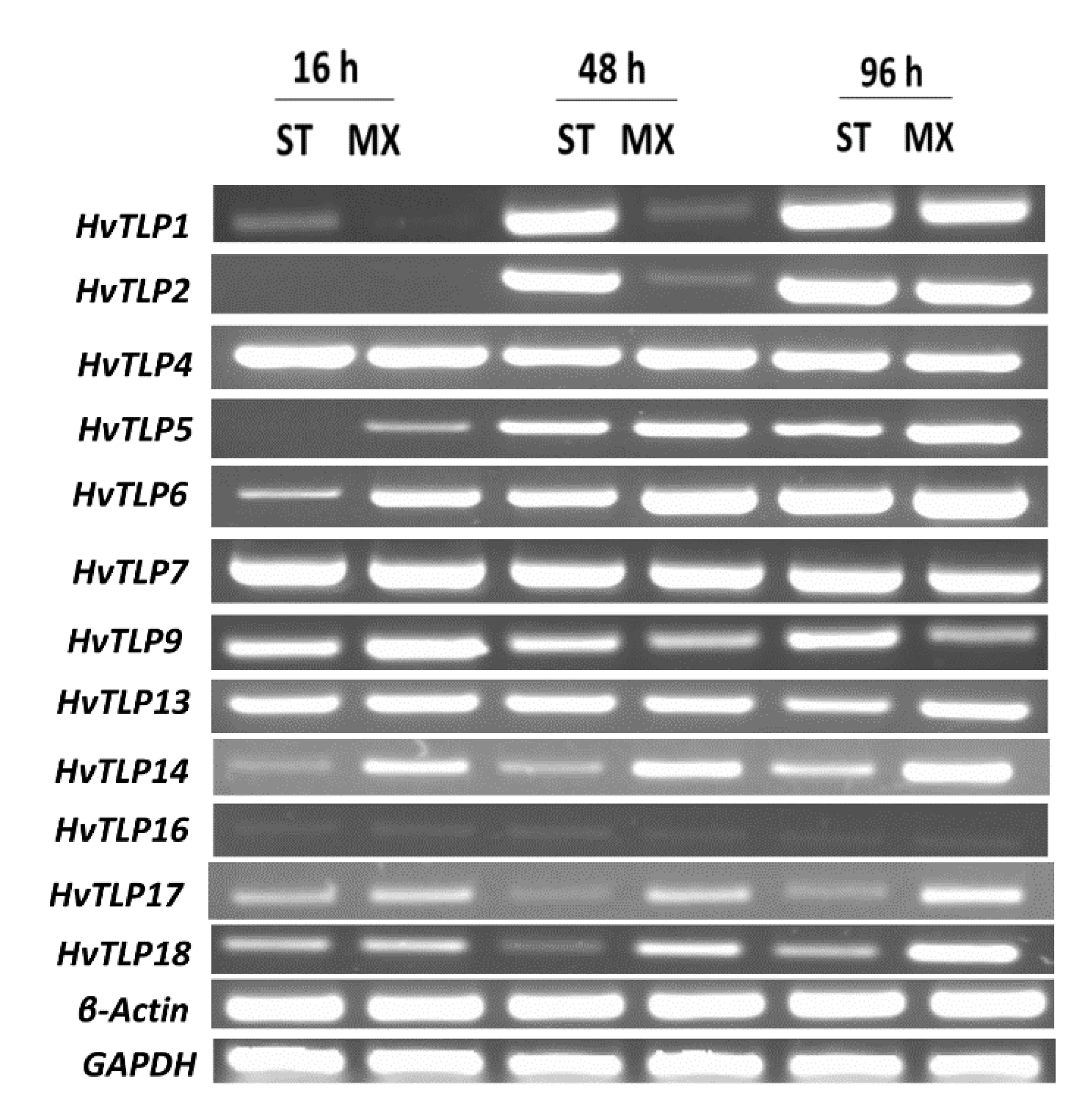

3.7. Transcript Abundance of HvTLPs during Different Stages of Barley Seed Germination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brandazza, A.; Angeli, S.; Tegoni, M.; Cambillau, C.; Pelosi, P. Plant stress proteins of the thaumatin-like family discovered in animals. FEBS Lett. 2004, 572, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Tripathi, R.K.; Lemaux, P.G.; Buchanan, B.B.; Singh, J. Redox-dependent interaction between thaumatin-like protein and β-glucan influences malting quality of barley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7725–7730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fils-Lycaon, B.R.; Wiersma, P.A.; Eastwell, K.C.; Sautiere, P. A cherry protein and its gene, abundantly expressed in ripening fruit, have been identified as thaumatin-like. Plant Physiol. 1996, 111, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, L.C.; Rep, M. Pieterse CM: Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Velazhahan, R.; Datta, S.K.; Muthukrishnan, S. The PR-5 family: Thaumatin-like proteins. In Pathogenesis-Related Proteins in Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Petre, B.; Major, I.; Rouhier, N.; Duplessis, S. Genome-wide analysis of eukaryote thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs) with an emphasis on poplar. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, R.; Chakrabarti, C. Crystal structure analysis of NP24-I: A thaumatin-like protein. Planta 2008, 228, 883–890. [Google Scholar]

- Fierens, E.; Gebruers, K.; Voet, A.R.; De Maeyer, M.; Courtin, C.M.; Delcour, J.A. Biochemical and structural characterization of TLXI, the Triticum aestivum L. thaumatin-like xylanase inhibitor. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 646–654. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Sturrock, R.; Ekramoddoullah, A.K. The superfamily of thaumatin-like proteins: Its origin, evolution, and expression towards biological function. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Aguero, C.B.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Walker, M.A.; Lu, J. Overexpression of a thaumatin-like protein gene from Vitis amurensis improves downy mildew resistance in Vitis vinifera grapevine. Protoplasma 2017, 254, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam, K.; Arun, M.; Mariashibu, T.S.; Theboral, J.; Rajesh, M.; Singh, N.K.; Manickavasagam, M.; Ganapathi, A. Overexpression of tobacco osmotin (Tbosm) in soybean conferred resistance to salinity stress and fungal infections. Planta 2012, 236, 1909–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, K.; Pal, A.K.; Gulati, A.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K.; Ahuja, P.S. Overexpression of Camellia sinensis thaumatin-like protein, CsTLP in potato confers enhanced resistance to Macrophomina phaseolina and Phytophthora infestans infection. Mol. Biotechnol. 2013, 54, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chun, J.; Yu, X.; Griffith, M. Genetic studies of antifreeze proteins and their correlation with winter survival in wheat. Euphytica 1998, 102, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, R.A.; Tikhonova, I.; Bordelon, B.P.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bressan, R.A. Coordinate accumulation of antifungal proteins and hexoses constitutes a developmentally controlled defense response during fruit ripening in grape. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seo, P.J.; Lee, A.-K.; Xiang, F.; Park, C.-M. Molecular and functional profiling of Arabidopsis pathogenesis-related genes: Insights into their roles in salt response of seed germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Lv, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Ding, L. Expansion and evolution of thaumatin-like protein (TLP) gene family in six plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 79, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, K.; Russell, J.; Schreiber, M.; Halpin, C.; Oakey, H.; Washington, J.M.; Booth, A.; Shirley, N.J.; Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B. A genome wide association scan for (1, 3; 1, 4)-β-glucan content in the grain of contemporary 2-row Spring and Winter barleys. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 907. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, J.; Wu, F. The changes of β-glucan content and β-glucanase activity in barley before and after malting and their relationships to malt qualities. Food Chem. 2004, 86, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hejgaard, J.; Jacobsen, S.; Svendsen, I. Two antifungal thaumatin-like proteins from barley grain. FEBS Lett. 1991, 291, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjanović, S.; Beljanski, M.V.; Gavrović-Jankulović, M.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Pavlović, M.D.; Bejosano, F. Antimicrobial Activity of Malting Barley Grain Thaumatin-Like Protein Isoforms, S and R. J. Inst. Brew. 2007, 113, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Osmond, R.I.; Hrmova, M.; Fontaine, F.; Imberty, A.; Fincher, G.B. Binding interactions between barley thaumatin-like proteins and (1, 3)-β-D-glucans: Kinetics, specificity, structural analysis and biological implications. FEBS J. 2001, 268, 4190–4199. [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; Von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenteros, J.J.A.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; Von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, A.K.; Mohan, A.; Gill, K.S. Comparative analysis of ABCB1 reveals novel structural and functional conservation between monocots and dicots. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Boil. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, S.; Dhugga, K.S.; Beech, R.N.; Singh, J. Genome-wide analysis of the cellulose synthase-like (Csl) gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Dhugga, K.S.; Gill, K.; Singh, J. Novel Structural and Functional Motifs in cellulose synthase (CesA) Genes of Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.K.; Goel, R.; Kumari, S.; Dahuja, A. Genomic organization, phylogenetic comparison, and expression profiles of the SPL family genes and their regulation in soybean. Dev. Genes Evol. 2017, 227, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, K.; Singh, J. A root-specific wall-associated kinase gene, HvWAK1, regulates root growth and is highly divergent in barley and other cereals. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2013, 13, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Kumar, K.R.R.; Kumar, D.; Shukla, P.; Kirti, P. Characterization of a pathogen induced thaumatin-like protein gene AdTLP from Arachis diogoi, a wild peanut. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Abu-Ghannam, N.; Gallaghar, E. Barley for brewing: Characteristic changes during malting, brewing and applications of its by-products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierens, E.; Rombouts, S.; Gebruers, K.; Goesaert, H.; Brijs, K.; Beaugrand, J.; Volckaert, G.; Van Campenhout, S.; Proost, P.; Courtin, C.M.; et al. TLXI, a novel type of xylanase inhibitor from wheat (Triticum aestivum) belonging to the thaumatin family. Biochem. J. 2007, 403, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, A.H.; Bowers, J.E.; Bruggmann, R.; Dubchak, I.; Grimwood, J.; Gundlach, H.; Haberer, G.; Hellsten, U.; Mitros, T.; Poliakov, A. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 2009, 457, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, T.; Graner, A.; Waugh, R.; Große, I.; Close, T.J.; Stein, N. Evidence and evolutionary analysis of ancient whole-genome duplication in barley predating the divergence from rice. BMC Evol. Boil. 2009, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Ni, P.; Dong, W.; Hu, S.; Zeng, C. The genomes of Oryza sativa: A history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V. The origin of introns and their role in eukaryogenesis: A compromise solution to the introns-early versus introns-late debate? Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.K.; Bregitzer, P.; Singh, J. Genome-wide analysis of the SPL/miR156 module and its interaction with the AP2/miR172 unit in barley. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Tan, C.; Zhou, G.; Li, C. Involvement of Alternative Splicing in Barley Seed Germination. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wu, J.; Geng, S.; Feng, N.; Chen, F.; Kong, X.; Song, G.; Chen, K.; Li, A.; Mao, L. Regulation of FT splicing by an endogenous cue in temperate grasses. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Napoli, N.; Ghelli, R.; Brunetti, P.; De Paolis, A.; Cecchetti, V.; Tsuge, T.; Serino, G.; Matsui, M.; Mele, G.; Rinaldi, G.; et al. A Newly Identified Flower-Specific Splice Variant of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 Regulates Stamen Elongation and Endothecium Lignification in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 620–637. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.-Q.C.; Lin, L. Transcriptional regulatory programs underlying barley germination and regulatory functions of gibberellin and abscisic acid. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Singh, J. Seed development-related expression of ARGONAUTE4_9 class of genes in barley: Possible role in seed dormancy. Euphytica 2012, 188, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Deduced Protein | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | CDS Length (bp) | a.a | pI | MW (kDa) | No. Cysteine Residues | Chrom-osomal Location | Genomic Location | Exon No. | Subcellular Localization | Signal Peptide | TM Domain |

| HvTLP1 | HORVU7Hr1G122120.1 | 522 | 173 | 4.33 | 17.548 | 10 | 7H | 655448674-655449693 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP2 | HORVU7Hr1G122100.1 | 522 | 173 | 4.51 | 17.576 | 10 | 7H | 655345402-655345932 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP3 | HORVU5Hr1G017530.1 | 528 | 175 | 5.02 | 18.048 | 10 | 5H | 67689233-67690149 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP4 | HORVU5Hr1G005290.1 | 690 | 229 | 6.45 | 24.325 | 10 | 5H | 8764295-8765150 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP5 | HORVU5Hr1G005180.4 | 744 | 247 | 6.48 | 26.062 | 16 | 5H | 8598500-8736900 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP6 | HORVU5Hr1G005180.6 | 681 | 226 | 7.33 | 23.725 | 16 | 5H | 8614116-8615298 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP7 | HORVU5Hr1G051970.4 | 738 | 245 | 8.13 | 25.61 | 16 | 5H | 406435574-406436533 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP8 | HORVU4Hr1G002650.2 | 768 | 255 | 8.11 | 26.821 | 16 | 4H | 5073727-5074962 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP9 | HORVU7Hr1G057350.1 | 771 | 256 | 4.83 | 26.959 | 16 | 7H | 248978165-248980455 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP10 | HORVU5Hr1G005190.1 | 681 | 226 | 5.57 | 23.177 | 16 | 5H | 8603703-8604574 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP11 | HORVU1Hr1G005760.1 | 786 | 261 | 5.18 | 26.106 | 17 | 1H | 12508776-12510365 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP12 | HORVU5Hr1G084650.2 | 840 | 279 | 6.83 | 27.804 | 18 | 5H | 573025822-573026929 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP13 | HORVU3Hr1G086510.1 | 753 | 250 | 7.47 | 26.017 | 17 | 3H | 617523511-617524882 | 1 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP14 | HORVU3Hr1G012100.9 | 1026 | 341 | 5.33 | 38.477 | 22 | 3H | 26305708-26310551 | 1 | Plasma membrane | N-terminal | 2 |

| HvTLP15 | HORVU4Hr1G066130.4 | 780 | 259 | 4.79 | 25.744 | 16 | 4H | 550925586-550926443 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP16 | HORVU1Hr1G021650.3 | 777 | 258 | 8.43 | 27.097 | 17 | 1H | 88073476-88075764 | 2 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP17 | HORVU3Hr1G002210.5 | 1080 | 359 | 7.72 | 40.844 | 24 | 3H | 4627368-4637925 | 2 | Plasma membrane | N-terminal | 1 |

| HvTLP18 | HORVU5Hr1G112160.1 | 960 | 319 | 4.85 | 31.991 | 16 | 5H | 638398994-638401180 | 3 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

| HvTLP19 | HORVU4Hr1G063730.7 | 789 | 262 | 6.07 | 27.062 | 19 | 4H | 533492849-533494381 | 4 | Extracellular | N-terminal | 0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, I.; Tripathi, R.K.; Wilkins, O.; Singh, J. Thaumatin-Like Protein (TLP) Gene Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Exploration and Expression Analysis during Germination. Genes 2020, 11, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091080

Iqbal I, Tripathi RK, Wilkins O, Singh J. Thaumatin-Like Protein (TLP) Gene Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Exploration and Expression Analysis during Germination. Genes. 2020; 11(9):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091080

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Irfan, Rajiv Kumar Tripathi, Olivia Wilkins, and Jaswinder Singh. 2020. "Thaumatin-Like Protein (TLP) Gene Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Exploration and Expression Analysis during Germination" Genes 11, no. 9: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091080

APA StyleIqbal, I., Tripathi, R. K., Wilkins, O., & Singh, J. (2020). Thaumatin-Like Protein (TLP) Gene Family in Barley: Genome-Wide Exploration and Expression Analysis during Germination. Genes, 11(9), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091080