UBE2E1 Is Preferentially Expressed in the Cytoplasm of Slow-Twitch Fibers and Protects Skeletal Muscles from Exacerbated Atrophy upon Dexamethasone Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Constructs and Materials

2.2. Cell Culture and Knockdown Experiments

2.3. Animals and Knockdown Experiments

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.5. Protein Extraction

2.6. qRT-PCR

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

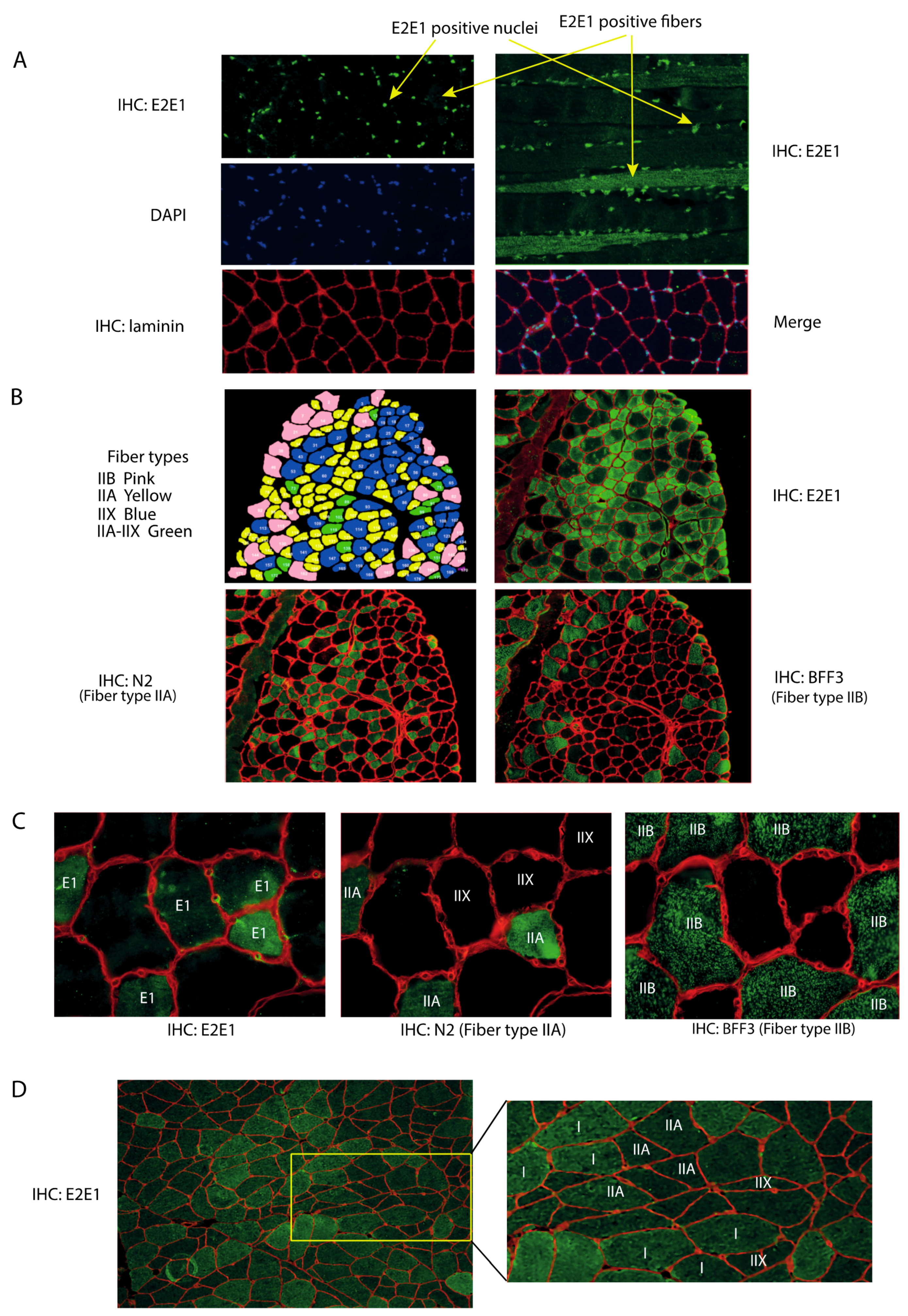

3.1. E2E1 Is Present in Both the Nuclei and the Cytoplasm of Mouse and Human Muscle Cells

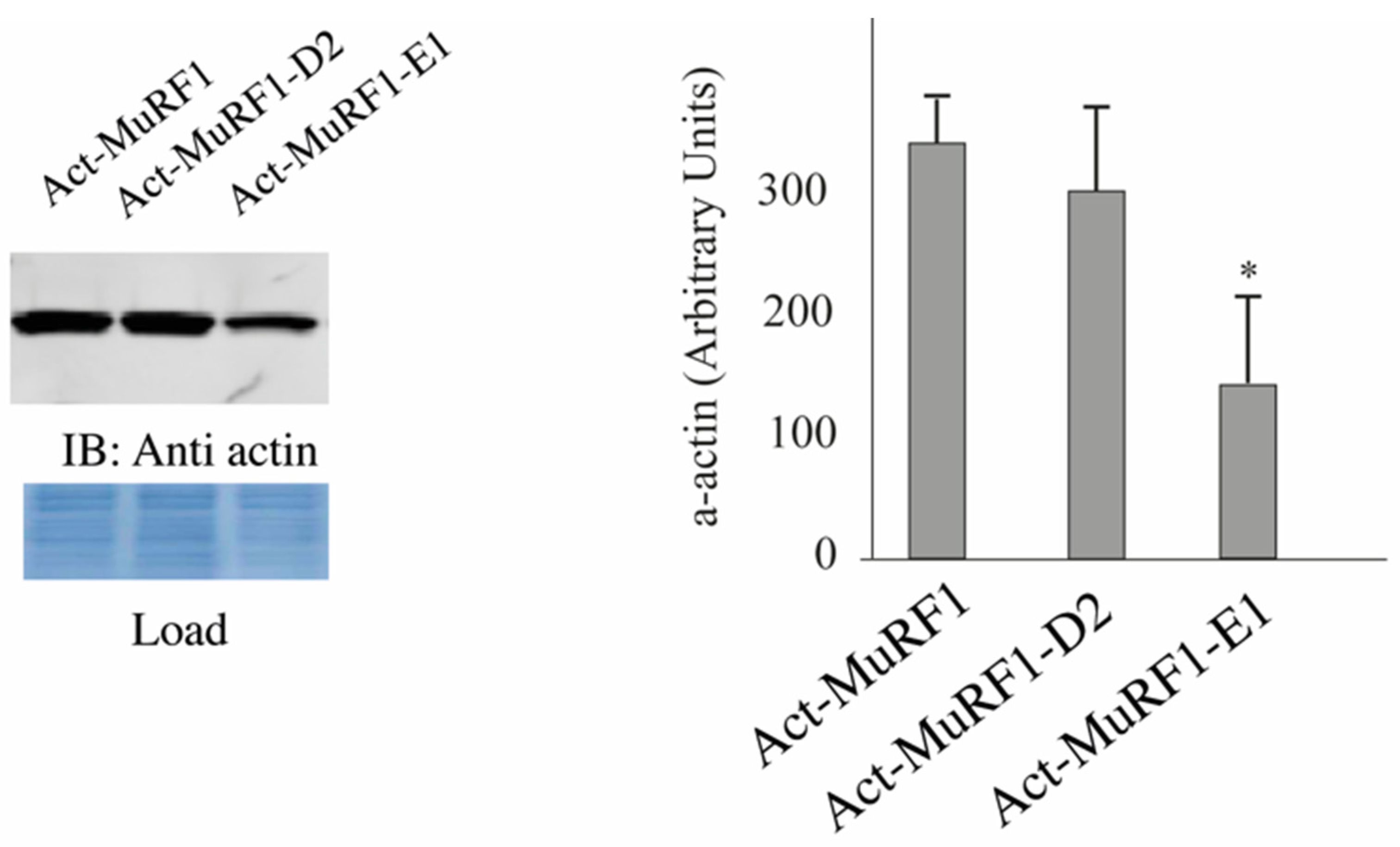

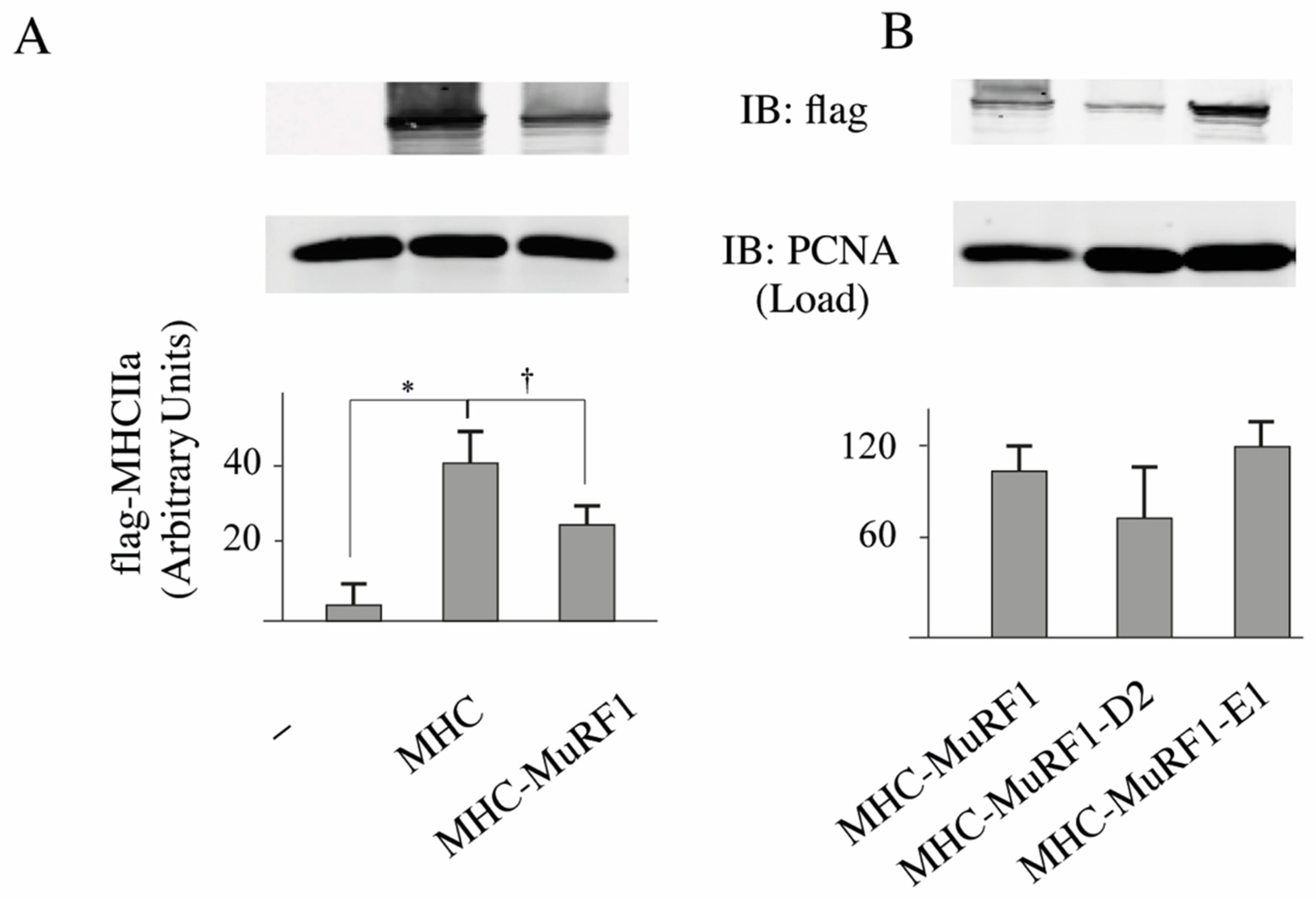

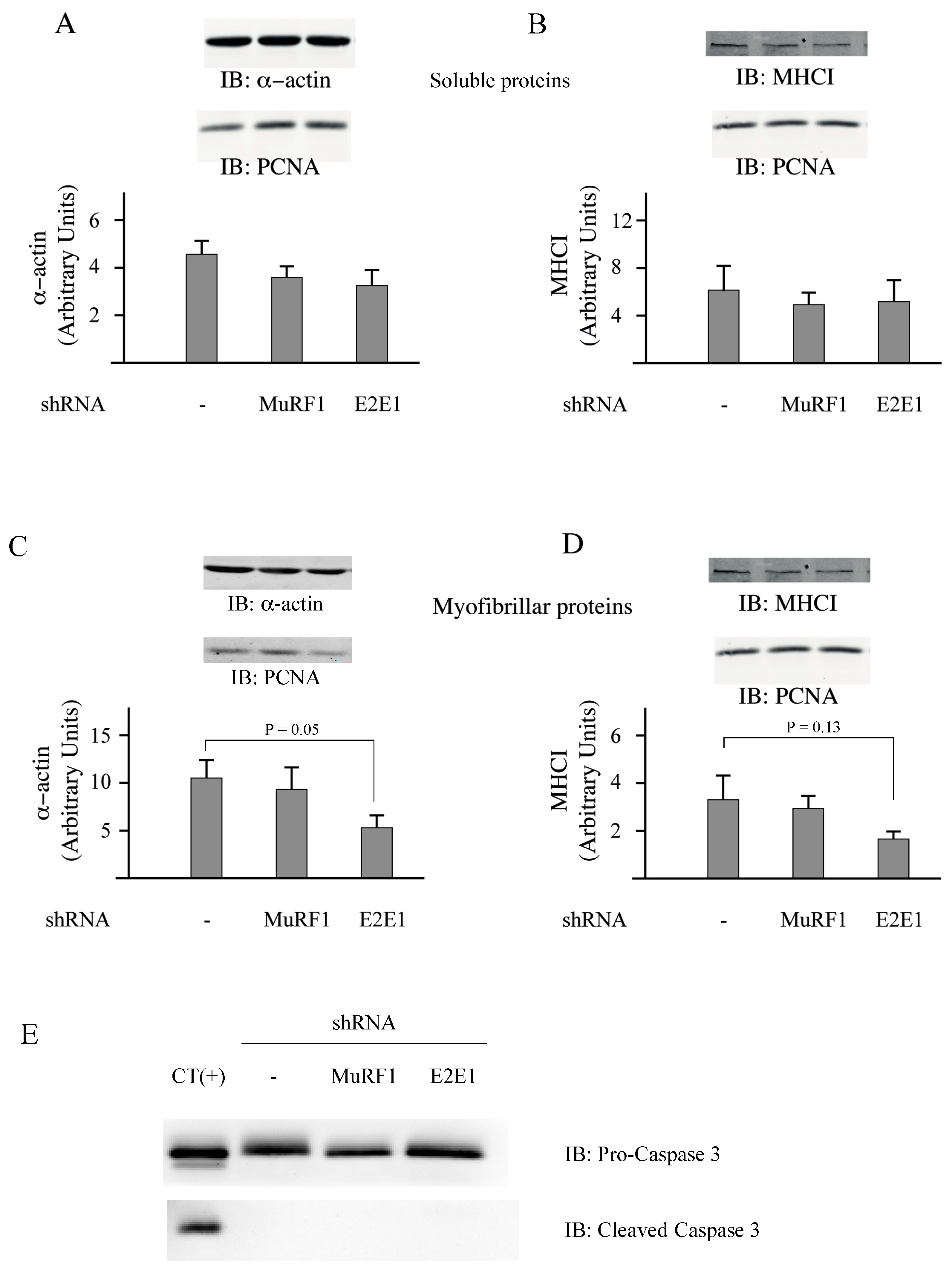

3.2. The MuRF1-E2E1 Couple Is Able to Target α-Actin But Not MHCIIa for Degradation in HEK293T Cells

3.3. E2E1 Repression Decreased α-Actin Levels and Tended to Depress MHCI Levels in Catabolic C2C12 Myotubes

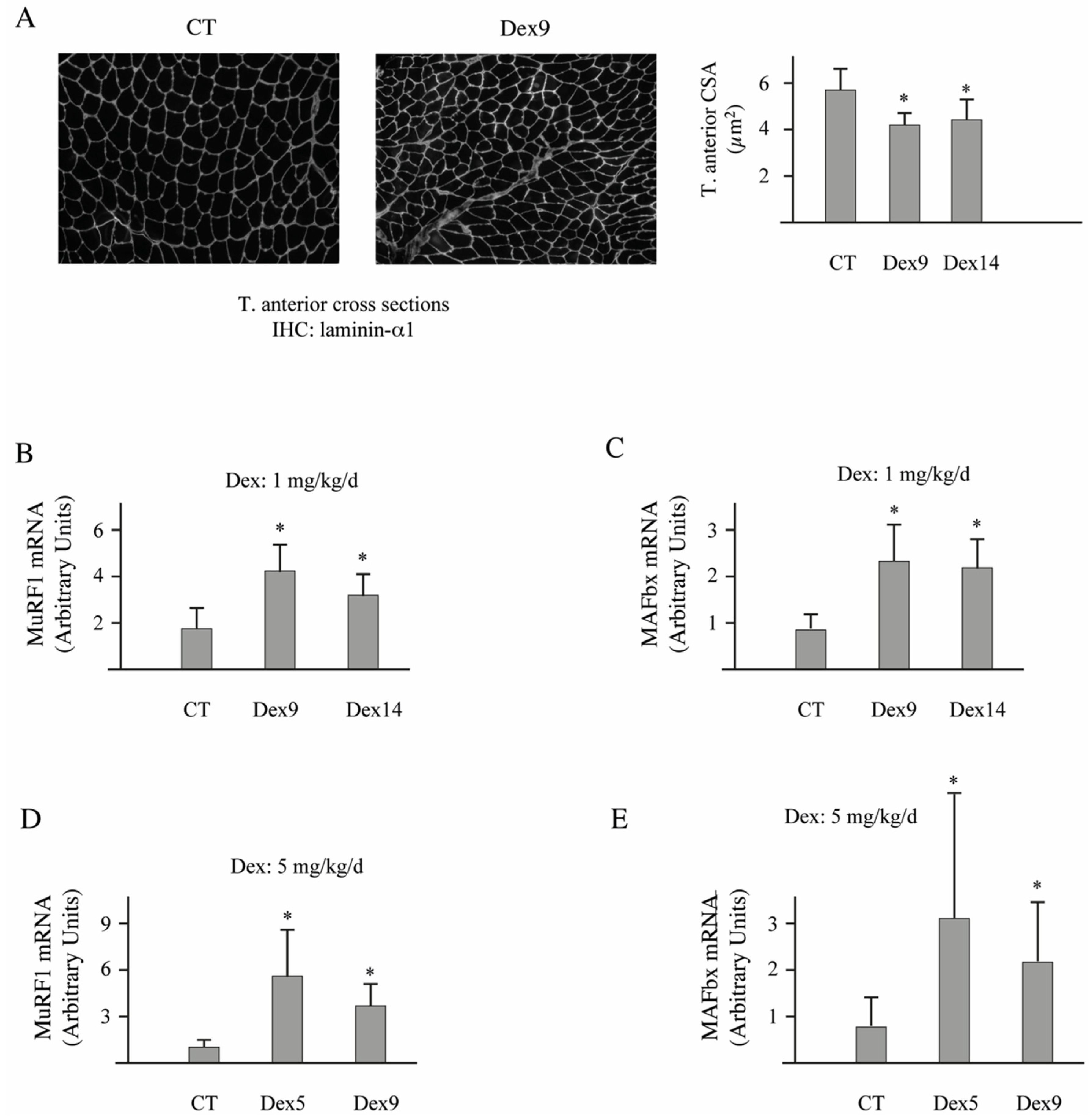

3.4. Dex-Treatment Induces Muscle Atrophy and Activates the UPS in Mice

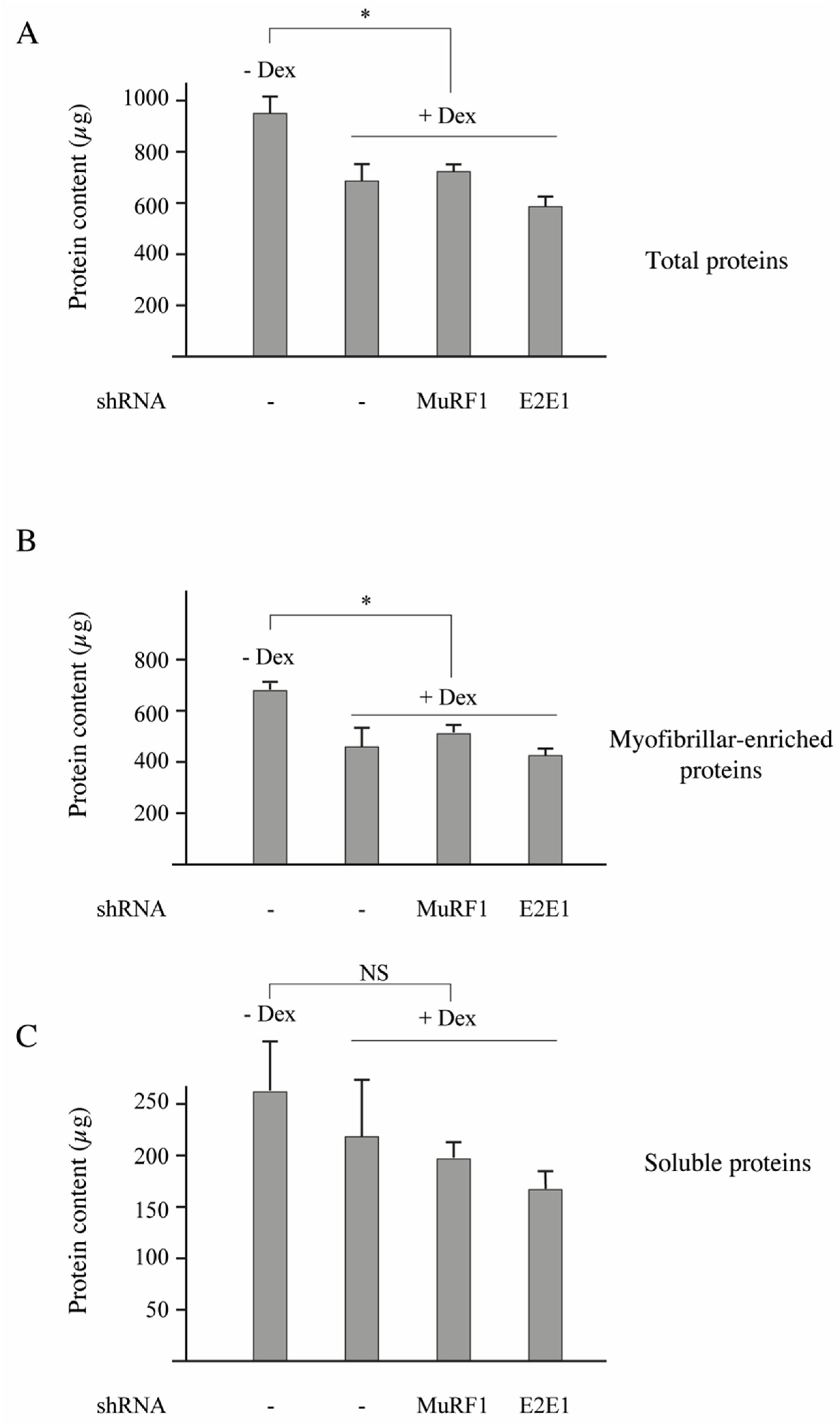

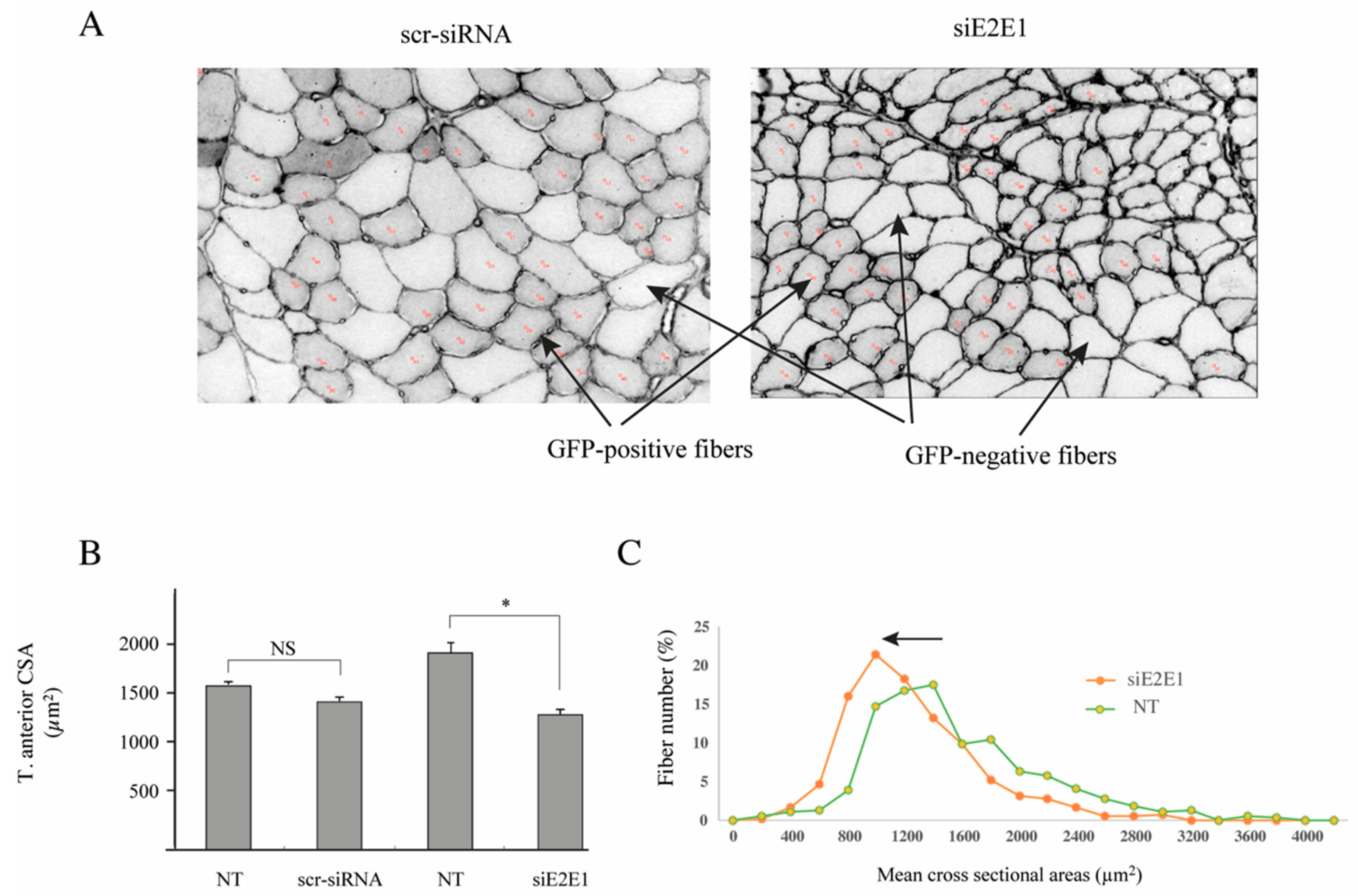

3.5. E2E1 Knockdown Aggravates Muscle Atrophy in Dex-Treated Mice

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearon, K.; Arends, J.; Baracos, V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nature reviews. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Von Haehling, S.; Anker, M.S.; Anker, S.D. Prevalence and clinical impact of cachexia in chronic illness in Europe, USA, and Japan: Facts and numbers update 2016. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: Role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2121–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pessin, J.E. Mechanisms for fiber-type specificity of skeletal muscle atrophy. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, J.; Maves, L. Skeletal muscle fiber type: Using insights from muscle developmental biology to dissect targets for susceptibility and resistance to muscle disease. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Dev. Biol. 2016, 5, 518–534. [Google Scholar]

- Ciciliot, S.; Rossi, A.C.; Dyar, K.A.; Blaauw, B.; Schiaffino, S. Muscle type and fiber type specificity in muscle wasting. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2191–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Pescatore, F.; Armani, A.; Paik, J.H.; Frasson, L.; Seydel, A.; Zhao, J.; Abraham, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaix, D.; Ventadour, S.; Codran, A.; Béchet, D.; Taillandier, D.; Combaret, L. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and skeletal muscle wasting. Essays Biochem. 2005, 41, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecker, S.H.; Jagoe, R.T.; Gilbert, A.; Gomes, M.; Baracos, V.; Bailey, J.; Price, S.R.; Mitch, W.E.; Goldberg, A.L. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Baehr, L.M. Skeletal muscle atrophy and the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E469–E484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Latres, E.; Baumhueter, S.; Lai, V.K.; Nunez, L.; Clarke, B.A.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Panaro, F.J.; Na, E.; Dharmarajan, K.; et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 2001, 294, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, B.A.; Drujan, D.; Willis, M.S.; Murphy, L.O.; Corpina, R.A.; Burova, E.; Rakhilin, S.V.; Stitt, T.N.; Patterson, C.; Latres, E.; et al. The E3 Ligase MuRF1 degrades myosin heavy chain protein in dexamethasone-treated skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielitz, J.; Kim, M.-S.; Shelton, J.M.; Latif, S.; Spencer, J.A.; Glass, D.J.; Richardson, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Myosin accumulation and striated muscle myopathy result from the loss of muscle RING finger 1 and 3. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2486–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedar, V.; McDonough, H.; Arya, R.; Li, H.H.; Rockman, H.A.; Patterson, C. Muscle-specific ring finger 1 is a bona fide ubiquitin ligase that degrades cardiac troponin I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 18135–18140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polge, C.; Cabantous, S.; Deval, C.; Claustre, A.; Hauvette, A.; Bouchenot, C.; Aniort, J.; Béchet, D.; Combaret, L.; Attaix, D.; et al. A muscle-specific MuRF1-E2 network requires stabilization of MuRF1-E2 complexes by telethonin, a newly identified substrate. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polge, C.; Heng, A.-E.; Jarzaguet, M.; Ventadour, S.; Claustre, A.; Combaret, L.; Bechet, D.; Matondo, M.; Uttenweiler-Joseph, S.; Monsarrat, B.; et al. Muscle actin is polyubiquitinylated in vitro and in vivo and targeted for breakdown by the E3 ligase MuRF1. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3790–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polge, C.; Attaix, D.; Taillandier, D. Role of E2-Ub-conjugating enzymes during skeletal muscle atrophy. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Van Wijk, S.J.; Timmers, H.T. The family of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s): Deciding between life and death of proteins. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markson, G.; Kiel, C.; Hyde, R.; Brown, S.; Charalabous, P.; Bremm, A.; Semple, J.; Woodsmith, J.; Duley, S.; Salehi-Ashtiani, K.; et al. Analysis of the human E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme protein interaction network. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, F.R.; Wilson, G.; Day, C.L. The N-terminal extension of UBE2E ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes limits chain assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 4099–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T.; Iwahara, S.; Saeki, Y.; Sasajima, H.; Yokosawa, H. Link between the ubiquitin conjugation system and the ISG15 conjugation system: ISG15 conjugation to the UbcH6 ubiquitin E2 enzyme. J. Biochem. 2005, 138, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Nowak, D.G.; Narula, N.; Robinson, B.; Watrud, K.; Ambrico, A.; Herzka, T.M.; Zeeman, M.E.; Minderer, M.; Zheng, W.; et al. The nuclear transport receptor Importin-11 is a tumor suppressor that maintains PTEN protein. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Plafker, K.S.; Starnes, A.; Cook, M.; Klevit, R.E.; Plafker, S.M. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, UbcM2, is restricted to monoubiquitylation by a two-fold mechanism that involves backside residues of E2 and Lys48 of ubiquitin. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 4004–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, D.E.; Brzovic, P.S.; Klevit, R.E. E2-BRCA1 RING interactions dictate synthesis of mono- or specific polyubiquitin chain linkages. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banka, P.A.; Behera, A.P.; Sarkar, S.; Datta, A.B. RING E3-Catalyzed E2 Self-Ubiquitination Attenuates the Activity of Ube2E Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 2290–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, L.M.; Jaffray, E.G.; Hay, R.T.; Meroni, G. Functional interactions between ubiquitin E2 enzymes and TRIM proteins. Biochem. J. 2011, 434, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, Y.; Ziv, T.; Admon, A.; Navon, A. The E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes direct polyubiquitination to preferred lysines. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 8595–8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkari, F.; Wheaton, K.; La Delfa, A.; Mohamed, M.; Shaikh, F.; Khatun, R.; Arrowsmith, C.H.; Frappier, L.; Saridakis, V.; Sheng, Y. Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 is a regulator of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbE2E1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16975–16985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, Y.; Ternette, N.; Edelmann, M.J.; Ziv, T.; Gayer, B.; Sertchook, R.; Dadon, Y.; Kessler, B.M.; Navon, A. E3 ligases determine ubiquitination site and conjugate type by enforcing specificity on E2 enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44104–44115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plafker, S.M.; Plafker, K.S.; Weissman, A.M.; Macara, I.G. Ubiquitin charging of human class III ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes triggers their nuclear import. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 167, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, K.; Sarkari, F.; Stanly Johns, B.; Davarinejad, H.; Egorova, O.; Kaustov, L.; Raught, B.; Saridakis, V.; Sheng, Y. UbE2E1/UBCH6 Is a Critical in Vivo E2 for the PRC1-catalyzed Ubiquitination of H2A at Lys-119. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2893–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polge, C.; Koulmann, N.; Claustre, A.; Jarzaguet, M.; Serrurier, B.; Combaret, L.; Béchet, D.; Bigard, X.; Attaix, D.; Taillandier, D. UBE2D2 is not involved in MuRF1-dependent muscle wasting during hindlimb suspension. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventadour, S.; Jarzaguet, M.; Wing, S.S.; Chambon, C.; Combaret, L.; Bechet, D.; Attaix, D.; Taillandier, D. A new method of purification of proteasome substrates reveals polyubiquitination of 20 S proteasome subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 5302–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, R.J.; Cagnin, S.; Chemello, F.; Silvestrin, M.; Musaro, A.; De Pitta, C.; Lanfranchi, G.; Sandri, M. Involvement of microRNAs in the regulation of muscle wasting during catabolic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 21909–21925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueugneau, M.; Coudy-Gandilhon, C.; Théron, L.; Meunier, B.; Barboiron, C.; Combaret, L.; Taillandier, D.; Polge, C.; Attaix, D.; Picard, B.; et al. Skeletal muscle lipid content and oxidative activity in relation to muscle fiber type in aging and metabolic syndrome. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochala, J.; Gustafson, A.-M.; Diez, M.L.; Renaud, G.; Li, M.; Aare, S.; Qaisar, R.; Banduseela, V.C.; Hedström, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Preferential skeletal muscle myosin loss in response to mechanical silencing in a novel rat intensive care unit model: Underlying mechanisms. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 2007–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElhinny, A.S.; Kakinuma, K.; Sorimachi, H.; Labeit, S.; Gregorio, C.C. Muscle-specific RING finger-1 interacts with titin to regulate sarcomeric M-line and thick filament structure and may have nuclear functions via its interaction with glucocorticoid modulatory element binding protein-1. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 157, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knöll, R.; Linke, W.A.; Zou, P.; Miocic, S.; Kostin, S.; Buyandelger, B.; Ku, C.H.; Neef, S.; Bug, M.; Schäfer, K.; et al. Telethonin deficiency is associated with maladaptation to biomechanical stress in the mammalian heart. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S. Muscle fiber type diversity revealed by anti-myosin heavy chain antibodies. FEBS J. 2018, 385, 3688–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menconi, M.; Gonnella, P.; Petkova, V.; Lecker, S.; Hasselgren, P.O. Dexamethasone and corticosterone induce similar, but not identical, muscle wasting responses in cultured L6 and C2C12 myotubes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashima, T.; Naito, M.; Tsuruo, T. Caspase-mediated cleavage of cytoskeletal actin plays a positive role in the process of morphological apoptosis. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Wang, X.; Miereles, C.; Bailey, J.L.; Debigare, R.; Zheng, S.; Price, S.R.; Mitch, W.E. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Q.; Zhao, G. Resveratrol induces apoptosis in SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells. Resveratrol induces apoptosis in SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 2949–2956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umeki, D.; Ohnuki, Y.; Mototani, Y.; Shiozawa, K.; Suita, K.; Fujita, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Saeki, Y.; Okumura, S. Protective Effects of Clenbuterol against Dexamethasone-Induced Masseter Muscle Atrophy and Myosin Heavy Chain Transition. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, E.K.; Rayavarapu, S.; Damsker, J.M.; Nagaraju, K. Glucocorticoid analogues: Potential therapeutic alternatives for treating inflammatory muscle diseases. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2012, 12, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, R.; Yamamoto, S.; Yasumoto, Y.; Oishi, K. Dosing schedule-dependent attenuation of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protzek, A.O.P.; Costa-Júnior, J.M.; Rezende, L.F.; Santos, G.J.; Araújo, T.G.; Vettorazzi, J.F.; Ortis, F.; Carneiro, E.M.; Rafacho, A.; Boschero, A.C. Augmented beta-Cell Function and Mass in Glucocorticoid-Treated Rodents Are Associated with Increased Islet Ir-beta/AKT/mTOR and Decreased AMPK/ACC and AS160 Signaling. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 983453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvaniti, K.; Ricquier, D.; Champigny, O.; Richard, D. Leptin and corticosterone have opposite effects on food intake and the expression of UCP1 mRNA in brown adipose tissue of lep(ob)/lep(ob) mice. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 4000–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gounarides, J.S.; Korach-André, M.; Killary, K.; Argentieri, G.; Turner, O.; Laurent, D. Effect of dexamethasone on glucose tolerance and fat metabolism in a diet-induced obesity mouse model. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aniort, J.; Polge, C.; Claustre, A.; Combaret, L.; Béchet, D.; Attaix, D.; Heng, A.-E.; Taillandier, D. Upregulation of MuRF1 and MAFbx participates to muscle wasting upon gentamicin-induced acute kidney injury. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, G.; Thomas, M.; Langley, B.; Somers, W.; Patel, K.; Kemp, C.F.; Sharma, M.; Kambadur, R. Titin-cap associates with, and regulates secretion of, Myostatin. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002, 193, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormaechea-Agulla, D.; Kim, Y.; Song, M.S.; Song, S.J. New Insights into the Role of E2s in the Pathogenesis of Diseases: Lessons Learned from UBE2O. Mol. Cells 2018, 41, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Wijk, S.J.L.; de Vries, S.J.; Kemmeren, P.; Huang, A.; Boelens, R.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Timmers, H.T.M. A comprehensive framework of E2-RING E3 interactions of the human ubiquitin-proteasome system. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009, 5, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dex 1 mg/d/kg | Dex 5 mg/d/kg | |||||

| CT | Dex9 | Dex14 | CT | Dex5 | Dex9 | |

| Mice (g) | 26.01 ± 1.8 | 22.6 ± 1.4 * | 21.9 ± 2.2 * | 28.1 ± 1.8 | 24.6 ± 0.4 * | 24.2 ± 0.6 * |

| Gastrocnemius (mg) | 133.5 ± 8.0 | 112.0 ± 2.4 * | 94.9 ± 10.3 * | 163.7 ± 8.6 | 117.2 ± 5.4 * | 118.4 ± 7.5 * |

| T. anterior (mg) | 42.9 ± 2.0 | 39.1 ± 0.7 * | 33.94 ± 3.8 * | 51.5 ± 1.5 | 40.2 ± 1.7 * | 43.7 ± 2.4 * |

| EDL (mg) | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 8.4 ± 0.4 * | 7.08 ± 1.0 * | 12 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 0.5 * | 9.1 ± 0.4 * |

| Soleus (mg) | 8.5 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 9.3 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.3 * | 7.9 ± 0.6 * |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polge, C.; Aniort, J.; Armani, A.; Claustre, A.; Coudy-Gandilhon, C.; Tournebize, C.; Deval, C.; Combaret, L.; Béchet, D.; Sandri, M.; et al. UBE2E1 Is Preferentially Expressed in the Cytoplasm of Slow-Twitch Fibers and Protects Skeletal Muscles from Exacerbated Atrophy upon Dexamethasone Treatment. Cells 2018, 7, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7110214

Polge C, Aniort J, Armani A, Claustre A, Coudy-Gandilhon C, Tournebize C, Deval C, Combaret L, Béchet D, Sandri M, et al. UBE2E1 Is Preferentially Expressed in the Cytoplasm of Slow-Twitch Fibers and Protects Skeletal Muscles from Exacerbated Atrophy upon Dexamethasone Treatment. Cells. 2018; 7(11):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7110214

Chicago/Turabian StylePolge, Cécile, Julien Aniort, Andrea Armani, Agnès Claustre, Cécile Coudy-Gandilhon, Clara Tournebize, Christiane Deval, Lydie Combaret, Daniel Béchet, Marco Sandri, and et al. 2018. "UBE2E1 Is Preferentially Expressed in the Cytoplasm of Slow-Twitch Fibers and Protects Skeletal Muscles from Exacerbated Atrophy upon Dexamethasone Treatment" Cells 7, no. 11: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7110214

APA StylePolge, C., Aniort, J., Armani, A., Claustre, A., Coudy-Gandilhon, C., Tournebize, C., Deval, C., Combaret, L., Béchet, D., Sandri, M., Attaix, D., & Taillandier, D. (2018). UBE2E1 Is Preferentially Expressed in the Cytoplasm of Slow-Twitch Fibers and Protects Skeletal Muscles from Exacerbated Atrophy upon Dexamethasone Treatment. Cells, 7(11), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7110214