Phenylketonuria Alters the Prefrontal Cortex Genome-Wide Expression Profile Regardless of the Mouse Genetic Background

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Brain Punches and RNA Extraction

2.3. Library Preparation, mRNA Sequencing, and Analysis

2.4. Behavioral Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

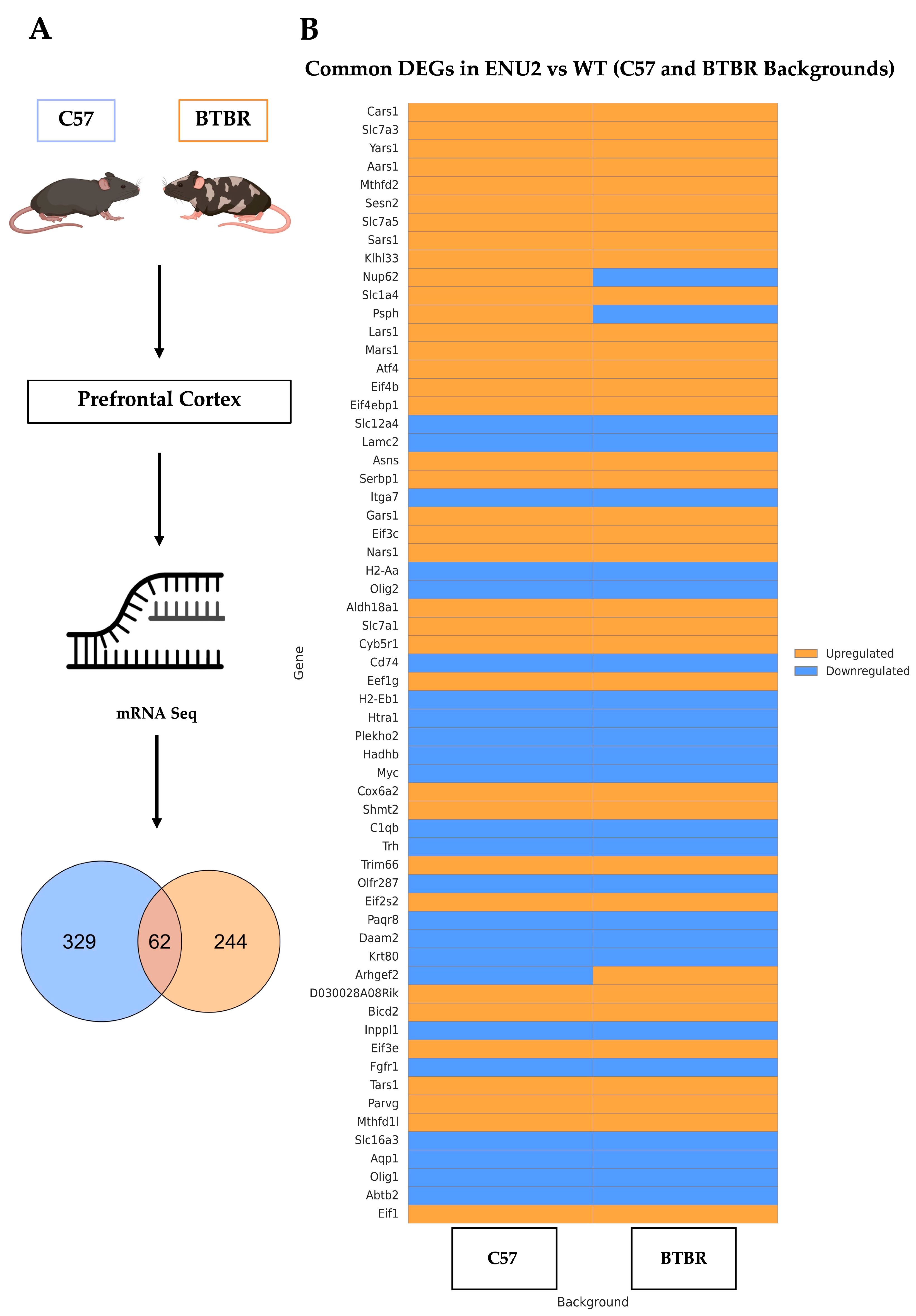

3.1. Transcriptomic Responses to enu2 Mutation Are Largely Conserved Across C57 and BTBR Backgrounds

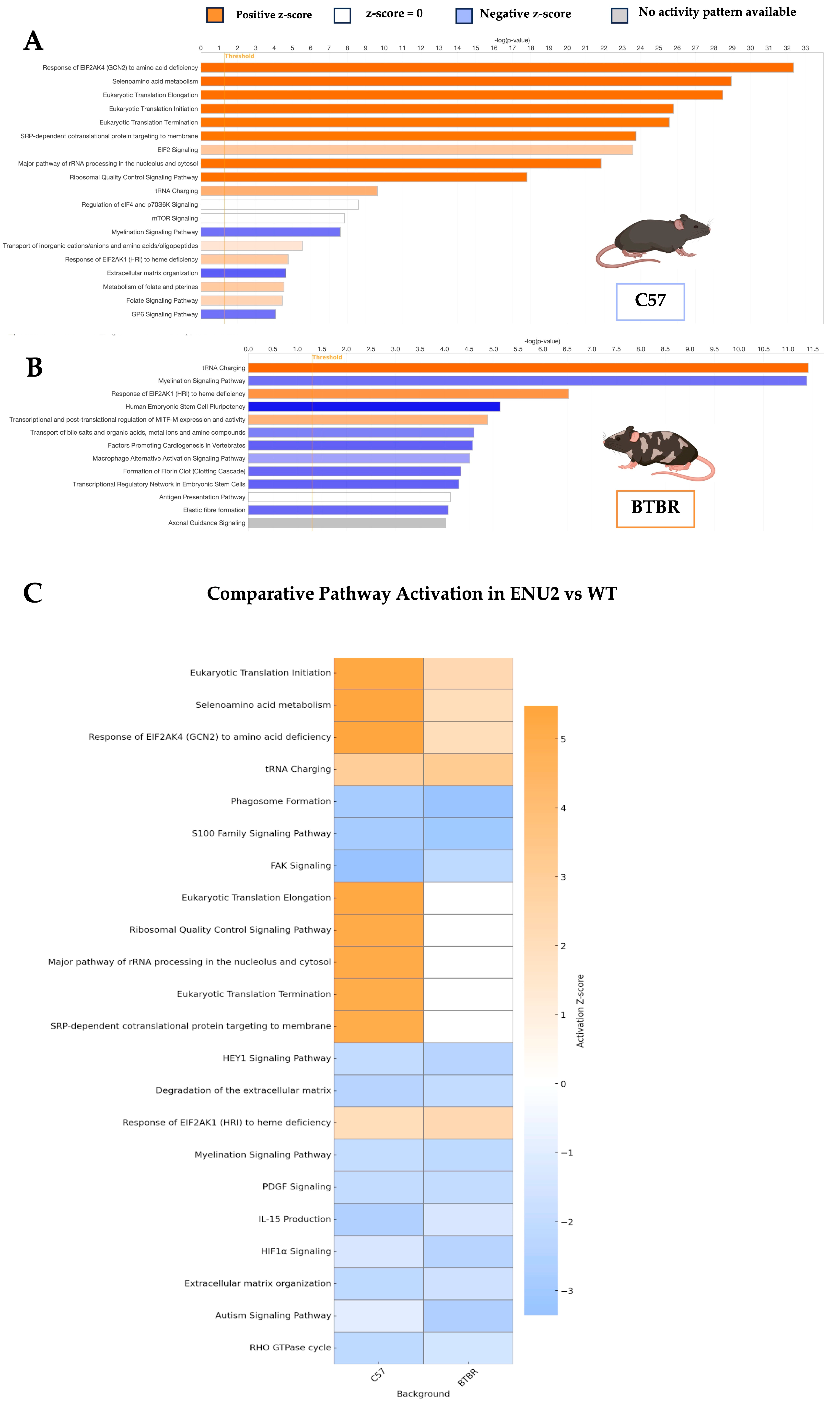

3.2. Activation of Translational and Metabolic Pathways in enu2 Mice Across Genetic Backgrounds

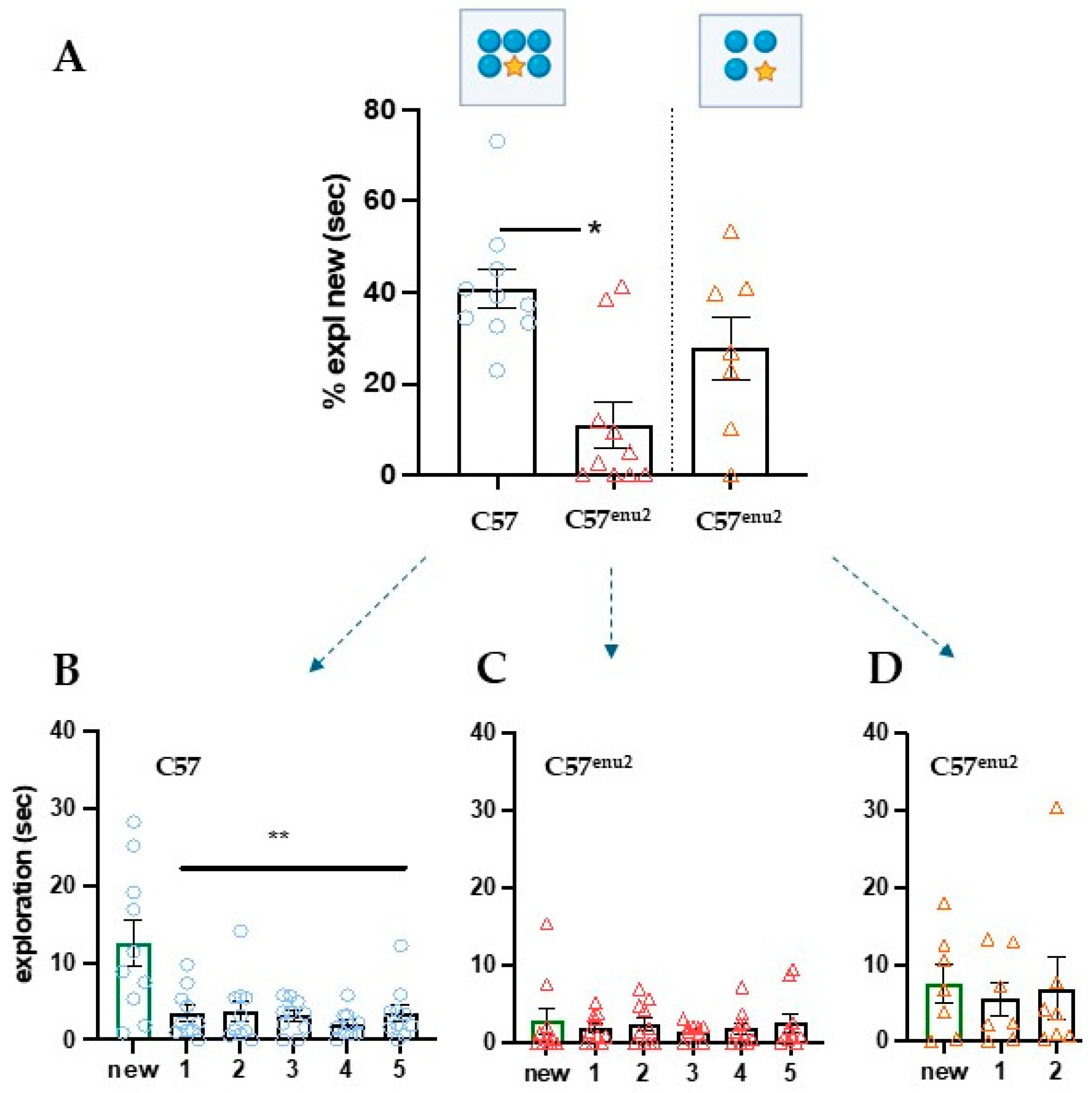

3.3. Increasing Attention Loading Also Highlights Deficits in C57enu2 Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PKU | phenylketonuria |

| HPA | hyperphenylalaninemia |

| pFC | prefrontal cortex |

| Phe | phenylalanine |

| Tyr | tyrosine |

| ETPKU | early-treated PKU |

| IQ | intellectual quotient |

| BTBR | Black and Tan Brachyury |

| C57 | C57Bl/6JRj |

| IOT | identical object task |

| WMC | working memory capacity |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| MBP | myelin basic protein |

References

- Diamond, A.; Prevor, M.B.; Callender, G.; Druin, D.P. Prefrontal Cortex Cognitive Deficits in Children Treated Early and Continuously for PKU. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1997, 62, i-206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuzzi, V.; Pansini, M.; Sechi, E.; Chiarotti, F.; Carducci, C.L.; Levi, G.; Antonozzi, I. Executive Function Impairment in Early-treated PKU Subjects with Normal Mental Development. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2004, 27, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, S.E.; Moffitt, A.J.; Peck, D. Disruption of Prefrontal Function and Connectivity in Individuals with Phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010, 99, S33–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, J.D.; Charlton, C.K. Characterization of mutations at the mouse phenylalanine hydroxylase locus. Genomics 1997, 39, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabib, S.; Pascucci, T.; Ventura, R.; Romano, V.; Puglisi-Allegra, S. The Behavioral Profile of Severe Mental Retardation in a Genetic Mouse Model of Phenylketonuria. Behav. Genet. 2003, 33, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, T.; Giacovazzo, G.; Andolina, D.; Accoto, A.; Fiori, E.; Ventura, R.; Orsini, C.; Conversi, D.; Carducci, C.; Leuzzi, V.; et al. Behavioral and Neurochemical Characterization of New Mouse Model of Hyperphenylalaninemia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolina, D.; Conversi, D.; Cabib, S.; Trabalza, A.; Ventura, R.; Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Pascucci, T. 5-Hydroxytryptophan during critical postnatal period improves cognitive performances and promotes dendritic spine maturation in genetic mouse model of phenylketonuria. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, T.; Rossi, L.; Colamartino, M.; Gabucci, C.; Carducci, C.; Valzania, A.; Sasso, V.; Bigini, N.; Pierigè, F.; Viscomi, M.T.; et al. A new therapy prevents intellectual disability in mouse with phenylketonuria. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 124, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, T.; Andolina, D.; La Mela, I.; Conversi, D.; Latagliata, C.; Ventura, R.; Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Cabib, S. 5-Hydroxytryptophan Rescues Serotonin Response to Stress in Prefrontal Cortex of Hyperphenylalaninaemic Mice. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 12, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, T.; Giacovazzo, G.; Andolina, D.; Conversi, D.; Cruciani, F.; Cabib, S.; Puglisi-Allegra, S. In Vivo Catecholaminergic Metabolism in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex of ENU2 Mice: An Investigation of the Cortical Dopamine Deficit in Phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012, 35, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, E.; Oddi, D.; Ventura, R.; Colamartino, M.; Valzania, A.; D’Amato, F.R.; Bruinenberg, V.; van der Zee, E.; Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Pascucci, T. Early-onset behavioral and neurochemical deficits in the genetic mouse model of phenylketonuria. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Goot, E.; Bruinenberg, V.M.; Hormann, F.M.; Eisel, U.L.M.; van Spronsen, F.J.; Van der Zee, E.A. Hippocampal Microglia Modifications in C57Bl/6 Pah and BTBR Pah Phenylketonuria (PKU) Mice Depend on the Genetic Background, Irrespective of Disturbed Sleep Patterns. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 160, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannino, S.; Russo, F.; Torromino, G.; Pendolino, V.; Calabresi, P.; De Leonibus, E. Role of the Dorsal Hippocampus in Object Memory Load. Learn. Mem. 2012, 19, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivito, L.; De Risi, M.; Russo, F.; De Leonibus, E. Effects of Pharmacological Inhibition of Dopamine Receptors on Memory Load Capacity. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 359, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivito, L.; Saccone, P.; Perri, V.; Bachman, J.L.; Fragapane, P.; Mele, A.; Huganir, R.L.; De Leonibus, E. Phosphorylation of the AMPA Receptor GluA1 Subunit Regulates Memory Load Capacity. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016, 221, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Risi, M.; Torromino, G.; Tufano, M.; Moriceau, S.; Pignataro, A.; Rivagorda, M.; Carrano, N.; Middei, S.; Settembre, C.; Ammassari-Teule, M.; et al. Mechanisms by Which Autophagy Regulates Memory Capacity in Ageing. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeksma, M.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; Pruim, J.; de Valk, H.W.; Paans, A.M.J.; van Spronsen, F.J. Phenylketonuria: High Plasma Phenylalanine Decreases Cerebral Protein Synthesis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 96, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, A.M.; Van Vliet, N.; Van Vliet, D.; Romani, C.; Huijbregts, S.C.; Van Der Goot, E.; Hovens, I.B.; van der Zee, E.A.; Kema, I.P.; Heiner-Fokkema, M.R.; et al. Correlations of blood and brain biochemistry in phenylketonuria: Results from the Pah-enu2 PKU mouse. Mol. Gen. Metab. 2021, 134, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, K.; Kelso, W.; Farrand, S.; Panetta, J.; Fazio, T.; De Jong, G.; Walterfang, M. Psychiatric and Cognitive Aspects of Phenylketonuria: The Limitations of Diet and Promise of New Treatments. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregalda, A.; Carducci, C.; Viscomi, M.T.; Pierigè, F.; Biagiotti, S.; Menotta, M.; Biancucci, F.; Pascucci, T.; Leuzzi, V.; Magnani, M.; et al. Myelin Basic Protein Recovery during PKU Mice Lifespan and the Potential Role of MicroRNAs on Its Regulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 180, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrova, N.A.; Lyubimova, D.I.; Mishina, D.M.; Lobanova, V.S.; Valieva, S.I.; Mityaeva, O.N.; Feoktistova, S.G.; Volchkov, P.Y. Experimental Animal Models of Phenylketonuria: Pros and Cons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wente, S.R.; Rout, M.P. The Nuclear Pore Complex and Nuclear Transport. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeken, J.; Detheux, M.; Fryns, J.P.; Collet, J.F.; Alliet, P.; Van Schaftingen, E. Phosphoserine Phosphatase Deficiency in a Patient with Williams Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 34, 594–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.H.; Schluesener, H.J. The Innate Immunity of the Central Nervous System in Chronic Pain: The Role of Toll-like Receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinenberg, V.M.; van der Goot, E.; van Vliet, D.; de Groot, M.J.; Mazzola, P.N.; Heiner-Fokkema, M.R.; van Faassen, M.; van Spronsen, F.J.; van der Zee, E.A. The Behavioral Consequence of Phenylketonuria in Mice Depends on the Genetic Background. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, S.R.; Dudley, S.; Scherer, T.; Rimann, N.; Thöny, B.; Boutros, S.; Krenik, D.; Raber, J.; Harding, C.O. Modeling the Cognitive Effects of Diet Discontinuation in Adults with Phenylketonuria (PKU) Using Pegvaliase Therapy in PAH-Deficient Mice. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 136, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuzzi, V.; Chiarotti, F.; Nardecchia, F.; van Vliet, D.; van Spronsen, F.J. Predictability and Inconsistencies of Cognitive Outcome in Patients with Phenylketonuria and Personalised Therapy: The Challenge for the Future Guidelines. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, C.; Olson, A.; Aitkenhead, L.; Baker, L.; Patel, D.; Van Spronsen, F.; MacDonald, A.; van Wegberg, A.; Huijbregts, S. Meta-Analyses of Cognitive Functions in Early-Treated Adults with Phenylketonuria. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 143, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.; Capdevila-Lacasa, C.; Segura, B.; Pané, A.; Moreno, P.J.; Garrabou, G.; Grau-Junyent, J.M.; Junqué, C. Diffusivity alterations related to cognitive performance and phenylalanine levels in early-treated adults with phenylketonuria. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2025, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, R.; Rummel, C.; McKinley, R.; Rebsamen, M.; Maissen-Abgottspon, S.; Kreis, R.; Radojewski, P.; Pospieszny, K.; Hochuli, M.; Wiest, R.; et al. Transient brain structure changes after high phenylalanine exposure in adults with phenylketonuria. Brain 2024, 147, 3863–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fiori, E.; Guzzo, S.M.; Lo Iacono, L.; Orsini, C.; Cabib, S.; Andolina, D.; Rossi, L.; Nardecchia, F.; Leuzzi, V.; Pascucci, T. Phenylketonuria Alters the Prefrontal Cortex Genome-Wide Expression Profile Regardless of the Mouse Genetic Background. Cells 2026, 15, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030227

Fiori E, Guzzo SM, Lo Iacono L, Orsini C, Cabib S, Andolina D, Rossi L, Nardecchia F, Leuzzi V, Pascucci T. Phenylketonuria Alters the Prefrontal Cortex Genome-Wide Expression Profile Regardless of the Mouse Genetic Background. Cells. 2026; 15(3):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030227

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiori, Elena, Serafina Manila Guzzo, Luisa Lo Iacono, Cristina Orsini, Simona Cabib, Diego Andolina, Luigia Rossi, Francesca Nardecchia, Vincenzo Leuzzi, and Tiziana Pascucci. 2026. "Phenylketonuria Alters the Prefrontal Cortex Genome-Wide Expression Profile Regardless of the Mouse Genetic Background" Cells 15, no. 3: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030227

APA StyleFiori, E., Guzzo, S. M., Lo Iacono, L., Orsini, C., Cabib, S., Andolina, D., Rossi, L., Nardecchia, F., Leuzzi, V., & Pascucci, T. (2026). Phenylketonuria Alters the Prefrontal Cortex Genome-Wide Expression Profile Regardless of the Mouse Genetic Background. Cells, 15(3), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030227