Myosin-X Acts Upstream of L-Plastin to Drive Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes

Highlights

- Myo10 acts upstream of L-plastin in stress-induced TNT formation, defining a unidirectional Myo10 to L-plastin regulatory axis.

- L-plastin is a key structural effector for TNT abundance: upregulating L-plastin increases TNT-connected cells, while downregulating L-plastin reduces TNT-connected cells (with Myo10 and L-plastin co-localizing along TNTs and proto-TNTs).

- The Myo10 to L-plastin axis provides a mechanistic link between stress signaling and stable TNT formation by coupling Myo10-driven protrusion initiation to L-plastin–mediated actin-bundle stabilization.

- This highlights a potentially targetable pathway to modulate TNT networks in disease (e.g., cancer resilience/chemoresistance) or to enhance beneficial TNT-dependent transfer (e.g., mitochondrial rescue in injured/stressed cells).

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Antibodies, Transfection and Transduction

2.2. Transient Transfection of GFP-L-Plastin and GFP-Myo10 in CAD Cells and TNT Counting

2.3. Lentiviral Particle Transduction and TNT Counting

2.4. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

2.5. Cell Lysis, Gel Electrophoresis, and Western Blotting

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. L-Plastin Localizes to Stressed-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes and Proto-TNTs

3.2. Overexpression of L-Plastin Increases TNT Formation

3.3. Knockdown of L-Plastin Reduces TNT Numbers

3.4. L-Plastin Levels Do Not Reciprocally Regulate Myosin-X Expression

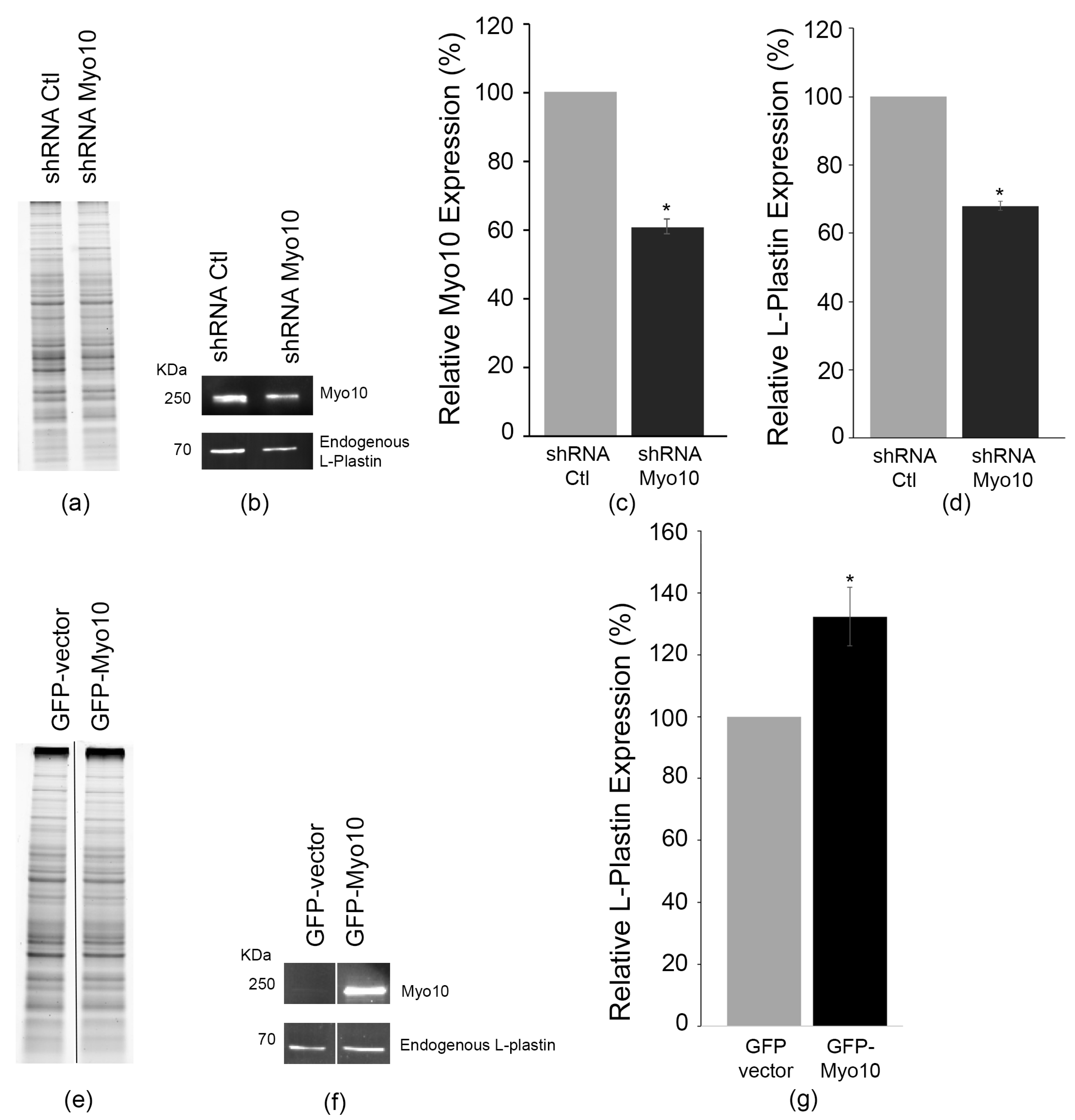

3.5. Myosin-X Controls L-Plastin Protein Abundance and TNT Formation

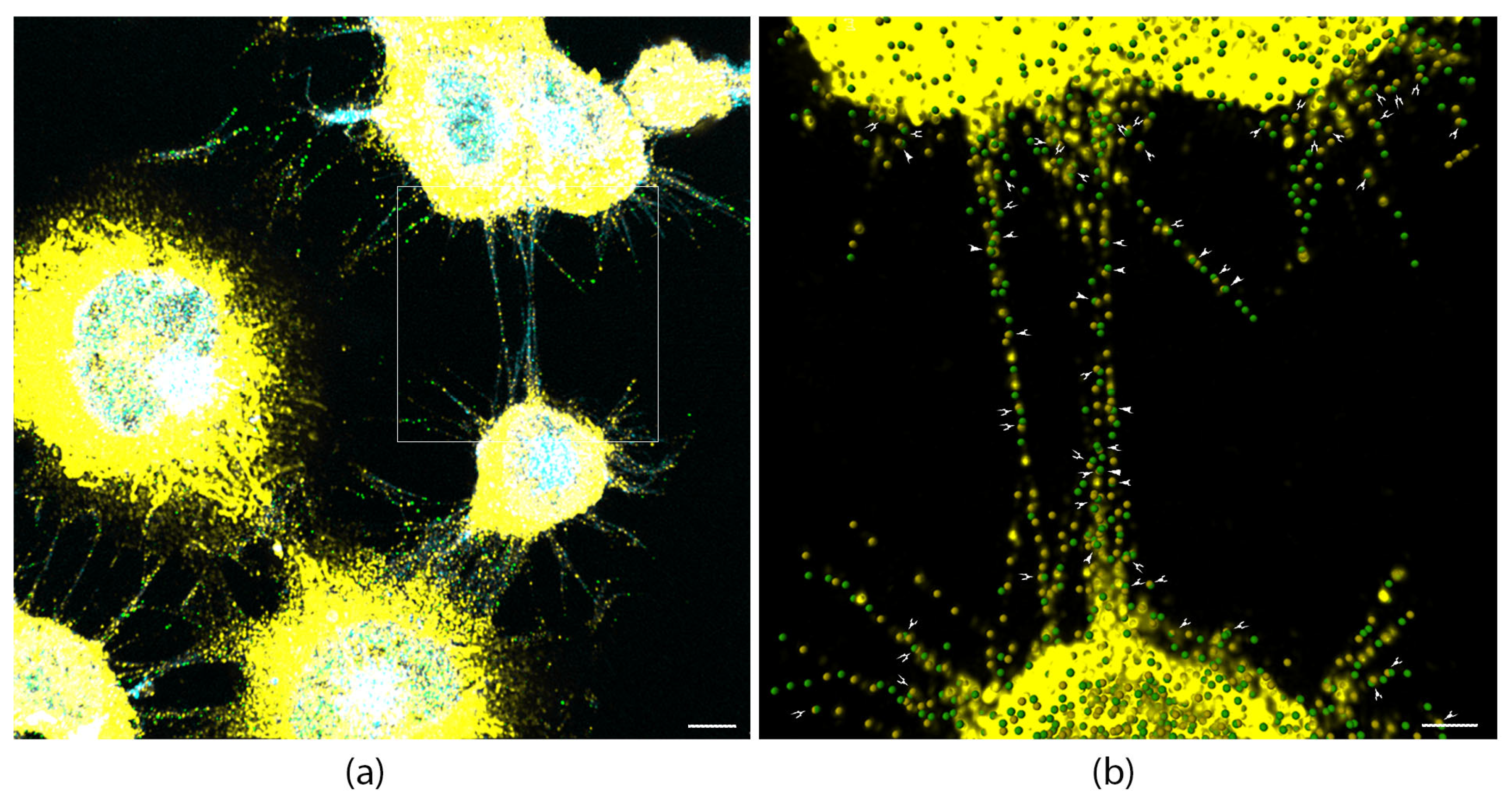

3.6. Myosin-X and L-Plastin Co-Localize in TNTs and Proto-TNTs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TNT | Tunneling nanotube |

| CAD | Cath. a-differentiated neuronal cells |

| Myo10 | Myosin-X |

| LCP1 | L-plastin |

| Proto-TNT | Filopodia-like TNT precursor |

| HIV-1 | Human Immunodeficiency Virus, type 1 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Ca2+ | Calcium |

| PIP3 | Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| PH | Pleckstrin homology |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| SGK | Serum/Glucocorticoid-regulated Kinase |

| LCM | Laser Capture Microsdissection |

| WGA | Wheat Germ Agglutinin |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| DTBP | Dithiobispropionimidate |

| shRNA | Short hairpin RNAPBS |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| TCE | 2,2,2-Trichloroethanol |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| TBST | Tris Buffered Saline with 0.1% Tween |

| RT | Room temperature |

| Standard Error | S.E. |

| control | ctl |

| micrometer | um |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

References

- Rustom, A.; Saffrich, R.; Markovic, I.; Walther, P.; Gerdes, H.-H. Nanotubular Highways for Intercellular Organelle Transport. Science 2004, 303, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abounit, S.; Zurzolo, C. Wiring through Tunneling Nanotubes--from Electrical Signals to Organelle Transfer. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisakhtnezhad, S.; Khosravi, L. Emerging Physiological and Pathological Implications of Tunneling Nanotubes Formation between Cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 94, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdes, H.-H.; Rustom, A.; Wang, X. Tunneling Nanotubes, an Emerging Intercellular Communication Route in Development. Mech. Dev. 2013, 130, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gerdes, H.-H. Transfer of Mitochondria via Tunneling Nanotubes Rescues Apoptotic PC12 Cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.N.; Das, S.R.; Emin, M.T.; Wei, M.; Sun, L.; Westphalen, K.; Rowlands, D.J.; Quadri, S.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, J. Mitochondrial Transfer from Bone-Marrow-Derived Stromal Cells to Pulmonary Alveoli Protects against Acute Lung Injury. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onfelt, B.; Nedvetzki, S.; Benninger, R.K.P.; Purbhoo, M.A.; Sowinski, S.; Hume, A.N.; Seabra, M.C.; Neil, M.A.A.; French, P.M.W.; Davis, D.M. Structurally Distinct Membrane Nanotubes between Human Macrophages Support Long-Distance Vesicular Traffic or Surfing of Bacteria. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 8476–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spees, J.L.; Olson, S.D.; Whitney, M.J.; Prockop, D.J. Mitochondrial Transfer between Cells Can Rescue Aerobic Respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousset, K.; Schiff, E.; Langevin, C.; Marijanovic, Z.; Caputo, A.; Browman, D.T.; Chenouard, N.; de Chaumont, F.; Martino, A.; Enninga, J.; et al. Prions Hijack Tunnelling Nanotubes for Intercellular Spread. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugenin, E.A.; Gaskill, P.J.; Berman, J.W. Tunneling Nanotubes (TNT) Are Induced by HIV-Infection of Macrophages: A Potential Mechanism for Intercellular HIV Trafficking. Cell. Immunol. 2009, 254, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria, G.S.; Zurzolo, C. Trafficking and Degradation Pathways in Pathogenic Conversion of Prions and Prion-like Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Virus Res. 2015, 207, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desir, S.; Wong, P.; Turbyville, T.; Chen, D.; Shetty, M.; Clark, C.; Zhai, E.; Romin, Y.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Starr, T.K.; et al. Intercellular Transfer of Oncogenic KRAS via Tunneling Nanotubes Introduces Intracellular Mutational Heterogeneity in Colon Cancer Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayanithy, V.; Dickson, E.L.; Steer, C.; Subramanian, S.; Lou, E. Tumor-Stromal Cross Talk: Direct Cell-to-Cell Transfer of Oncogenic microRNAs via Tunneling Nanotubes. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2014, 164, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquier, J.; Guerrouahen, B.S.; Al Thawadi, H.; Ghiabi, P.; Maleki, M.; Abu-Kaoud, N.; Jacob, A.; Mirshahi, M.; Galas, L.; Rafii, S.; et al. Preferential Transfer of Mitochondria from Endothelial to Cancer Cells through Tunneling Nanotubes Modulates Chemoresistance. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretschmer, A.; Zhang, F.; Somasekharan, S.P.; Tse, C.; Leachman, L.; Gleave, A.; Li, B.; Asmaro, I.; Huang, T.; Kotula, L.; et al. Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes Support Treatment Adaptation in Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdebenito, S.; Malik, S.; Luu, R.; Loudig, O.; Mitchell, M.; Okafo, G.; Bhat, K.; Prideaux, B.; Eugenin, E.A. Tunneling Nanotubes, TNT, Communicate Glioblastoma with Surrounding Non-Tumor Astrocytes to Adapt Them to Hypoxic and Metabolic Tumor Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, V.; Koganti, R.; Russell, G.; Sharma, A.; Shukla, D. Role of Tunneling Nanotubes in Viral Infection, Neurodegenerative Disease, and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 680891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Chang, X.; Chen, C.; Guo, Z.; Yu, G.; Shao, W.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, F.; et al. ROS/mtROS Promotes TNTs Formation via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway to Protect against Mitochondrial Damages in Glial Cells Induced by Engineered Nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, J.Y.; Loria, F.; Wu, Y.-J.; Córdova, G.; Nonaka, T.; Bellow, S.; Syan, S.; Hasegawa, M.; van Woerden, G.M.; Trollet, C.; et al. The Wnt/Ca2+ Pathway Is Involved in Interneuronal Communication Mediated by Tunneling Nanotubes. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.S.; Cheney, R.E. Myosin-X Is an Unconventional Myosin That Undergoes Intrafilopodial Motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuo, H.; Ikebe, M. Myosin X Transports Mena/VASP to the Tip of Filopodia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 319, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousset, K.; Marzo, L.; Commere, P.-H.; Zurzolo, C. Myo10 Is a Key Regulator of TNT Formation in Neuronal Cells. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 4424–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerber, M.L.; Cheney, R.E. Myosin-X: A MyTH-FERM Myosin at the Tips of Filopodia. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 3733–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Berg, J.S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lång, P.; Sousa, A.D.; Bhaskar, A.; Cheney, R.E.; Strömblad, S. Myosin-X Provides a Motor-Based Link between Integrins and the Cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquemet, G.; Hamidi, H.; Ivaska, J. Filopodia in Cell Adhesion, 3D Migration and Cancer Cell Invasion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miihkinen, M.; Grönloh, M.L.B.; Popović, A.; Vihinen, H.; Jokitalo, E.; Goult, B.T.; Ivaska, J.; Jacquemet, G. Myosin-X and Talin Modulate Integrin Activity at Filopodia Tips. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthis, N.J.; Wegener, K.L.; Ye, F.; Kim, C.; Goult, B.T.; Lowe, E.D.; Vakonakis, I.; Bate, N.; Critchley, D.R.; Ginsberg, M.H.; et al. The Structure of an Integrin/Talin Complex Reveals the Basis of inside-out Signal Transduction. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3623–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquemet, G.; Baghirov, H.; Georgiadou, M.; Sihto, H.; Peuhu, E.; Cettour-Janet, P.; He, T.; Perälä, M.; Kronqvist, P.; Joensuu, H.; et al. L-Type Calcium Channels Regulate Filopodia Stability and Cancer Cell Invasion Downstream of Integrin Signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasca, A.; Astleford, K.; Lederman, A.; Jensen, E.D.; Lee, B.S.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Mansky, K.C. Regulation of Osteoclast Differentiation by Myosin X. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, J.; Gujarathi, S.; Waheed, A.A.; Gordon, A.; Freed, E.O.; Gousset, K. Myosin-X Is Essential to the Intercellular Spread of HIV-1 Nef through Tunneling Nanotubes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 13, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignjevic, D.; Kojima, S.; Aratyn, Y.; Danciu, O.; Svitkina, T.; Borisy, G.G. Role of Fascin in Filopodial Protrusion. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J.M.; Ljubojevic, N.; Belian, S.; Chaze, T.; Castaneda, D.; Battistella, A.; Giai Gianetto, Q.; Matondo, M.; Descroix, S.; Bassereau, P.; et al. Tunnelling Nanotube Formation Is Driven by Eps8/IRSp53-Dependent Linear Actin Polymerization. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e113761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanote, V.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Gettemans, J. Plastins: Versatile Modulators of Actin Organization in (Patho)Physiological Cellular Processes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, S.C. The Actin-Bundling Protein L-Plastin: A Critical Regulator of Immune Cell Function. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 935173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffner-Reckinger, E.; Machado, R.A.C. The Actin-Bundling Protein L-Plastin-A Double-Edged Sword: Beneficial for the Immune Response, Maleficent in Cancer. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 355, 109–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinomiya, H. Plastin Family of Actin-Bundling Proteins: Its Functions in Leukocytes, Neurons, Intestines, and Cancer. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 213492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janji, B.; Giganti, A.; De Corte, V.; Catillon, M.; Bruyneel, E.; Lentz, D.; Plastino, J.; Gettemans, J.; Friederich, E. Phosphorylation on Ser5 Increases the F-Actin-Binding Activity of L-Plastin and Promotes Its Targeting to Sites of Actin Assembly in Cells. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, R.A.C.; Stojevski, D.; De Landtsheer, S.; Lucarelli, P.; Baron, A.; Sauter, T.; Schaffner-Reckinger, E. L-Plastin Ser5 Phosphorylation Is Modulated by the PI3K/SGK Pathway and Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Invasiveness. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2021, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.L.; Wang, J.; Turck, C.W.; Brown, E.J. A Role for the Actin-Bundling Protein L-Plastin in the Regulation of Leukocyte Integrin Function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 9331–9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, H.; Jensen, K.V.; Woodman, A.G.; Hyndman, M.E.; Vogel, H.J. The Calcium-Dependent Switch Helix of L-Plastin Regulates Actin Bundling. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babich, A.; Burkhardt, J.K. Coordinate Control of Cytoskeletal Remodeling and Calcium Mobilization during T-Cell Activation. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 256, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tanoury, Z.; Schaffner-Reckinger, E.; Halavatyi, A.; Hoffmann, C.; Moes, M.; Hadzic, E.; Catillon, M.; Yatskou, M.; Friederich, E. Quantitative Kinetic Study of the Actin-Bundling Protein L-Plastin and of Its Impact on Actin Turn-Over. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousset, K.; Gordon, A.; Kumar Kannan, S.; Tovar, J. A Novel Microproteomic Approach Using Laser Capture Microdissection to Study Cellular Protrusions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.; Kannan, S.K.; Gousset, K. A Novel Cell Fixation Method That Greatly Enhances Protein Identification in Microproteomic Studies Using Laser Capture Microdissection and Mass Spectrometry. Proteomics 2018, 18, e1700294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.; Gousset, K. Utilization of Laser Capture Microdissection Coupled to Mass Spectrometry to Uncover the Proteome of Cellular Protrusions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2259, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuella Martin, C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Bertin, A.; Geistlich, K.; Guyot, B.; Lefort, S.; Delay, E.; Dalverny, C.; Boissard, A.; Henry, C.; et al. Tunneling Nanotubes Propagate a BMP-Dependent Preneoplastic State 2025. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodneland, E.; Lundervold, A.; Gurke, S.; Tai, X.-C.; Rustom, A.; Gerdes, H.-H. Automated Detection of Tunneling Nanotubes in 3D Images. Cytom. Part J. Int. Soc. Anal. Cytol. 2006, 69, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurke, S.; Barroso, J.F.V.; Hodneland, E.; Bukoreshtliev, N.V.; Schlicker, O.; Gerdes, H.-H. Tunneling Nanotube (TNT)-like Structures Facilitate a Constitutive, Actomyosin-Dependent Exchange of Endocytic Organelles between Normal Rat Kidney Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 3669–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, D.M.; Shen, H.; Maki, C.G. Puromycin-Based Vectors Promote a ROS-Dependent Recruitment of PML to Nuclear Inclusions Enriched with HSP70 and Proteasomes. BMC Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Audenhove, I.; Denert, M.; Boucherie, C.; Pieters, L.; Cornelissen, M.; Gettemans, J. Fascin Rigidity and L-Plastin Flexibility Cooperate in Cancer Cell Invadopodia and Filopodia. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9148–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riplinger, S.M.; Wabnitz, G.H.; Kirchgessner, H.; Jahraus, B.; Lasitschka, F.; Schulte, B.; van der Pluijm, G.; van der Horst, G.; Hämmerling, G.J.; Nakchbandi, I.; et al. Metastasis of Prostate Cancer and Melanoma Cells in a Preclinical in Vivo Mouse Model Is Enhanced by L-Plastin Expression and Phosphorylation. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemke, M.; Rafael, M.T.; Wabnitz, G.H.; Weschenfelder, T.; Konstandin, M.H.; Garbi, N.; Autschbach, F.; Hartschuh, W.; Samstag, Y. Phosphorylation of Ectopically Expressed L-Plastin Enhances Invasiveness of Human Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.S.; Derfler, B.H.; Pennisi, C.M.; Corey, D.P.; Cheney, R.E. Myosin-X, a Novel Myosin with Pleckstrin Homology Domains, Associates with Regions of Dynamic Actin. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 3439–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramirez Perez, A.; Tovar, J.; Gousset, K. Myosin-X Acts Upstream of L-Plastin to Drive Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes. Cells 2026, 15, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030224

Ramirez Perez A, Tovar J, Gousset K. Myosin-X Acts Upstream of L-Plastin to Drive Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes. Cells. 2026; 15(3):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030224

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamirez Perez, Ana, Joey Tovar, and Karine Gousset. 2026. "Myosin-X Acts Upstream of L-Plastin to Drive Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes" Cells 15, no. 3: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030224

APA StyleRamirez Perez, A., Tovar, J., & Gousset, K. (2026). Myosin-X Acts Upstream of L-Plastin to Drive Stress-Induced Tunneling Nanotubes. Cells, 15(3), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030224