Neonatal Regulatory T Cells Mediate Fibrosis and Contribute to Cardiac Repair

Highlights

- Neonatal hearts display a distinct post-infarction immune profile characterized by the accumulation of CD4+Foxp3+ T (T-reg) cells with reparative transcriptional programs.

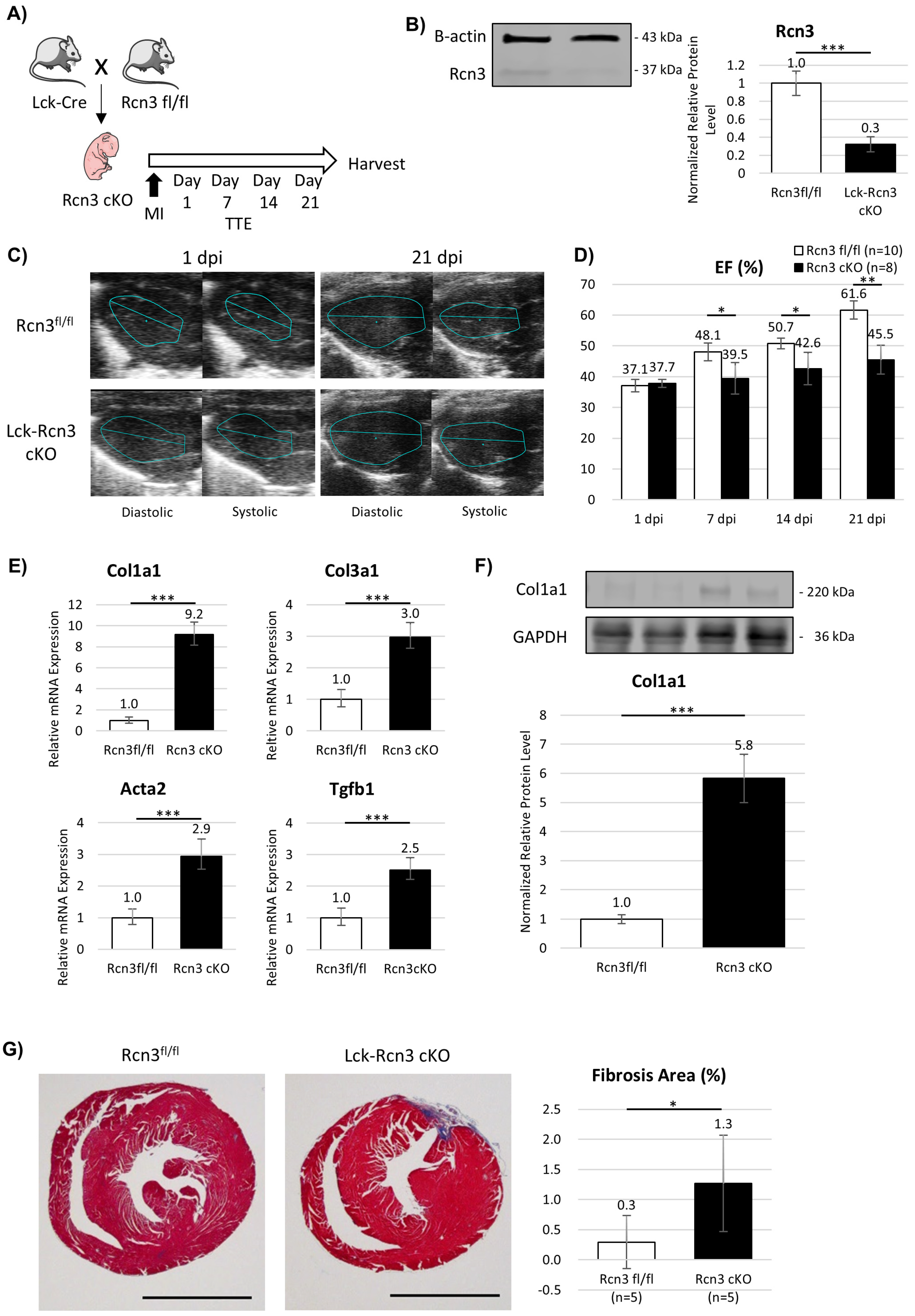

- Reticulocalbin 3 (Rcn3) is selectively upregulated in neonatal T-reg cells and is required for functional recovery and suppression of fibrosis after myocardial infarction.

- Neonatal T-reg cells actively contribute to cardiac repair by modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress responses and paracrine anti-fibrotic signaling.

- Targeting T-cell-specific pathways such as Rcn3 may represent a novel immunomodulatory strategy to enhance myocardial repair in the adult heart.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Myocardial Infarction Surgery

2.3. Transthoracic Echocardiography

2.4. Immune Cell Isolation from Heart Tissue

2.5. T-Cell Population Characterization and Flow Cytometry

2.6. RNA Sequencing and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.7. Adult Cardiac Fibroblast Isolation

2.8. Lentiviral Transduction of Jurkat Cells

2.9. Rcn3 Treatment Under Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress Conditions

2.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

2.12. Histological Analyses

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Age-Dependent Dynamics of Cardiac T Cells After Myocardial Infarction

3.2. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Distinct T-Cell Programs in Neonatal Versus Aged Hearts

3.3. Intracellular Rcn3 Enhances Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress Responses in T Cells

3.4. Rcn3 Suppresses Fibrotic Responses in Adult Cardiac Fibroblasts In Vitro

3.5. T-Cell-Specific Deletion of Rcn3 Impairs Neonatal Cardiac Repair In Vivo

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrello, E.R.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Simpson, E.; Johnson, B.A.; Grinsfelder, D.; Canseco, D.; Mammen, P.P.; Rothermel, B.A.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Regulation of neonatal and adult mammalian heart regeneration by the miR-15 family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrello, E.R.; Mahmoud, A.I.; Simpson, E.; Hill, J.A.; Richardson, J.A.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science 2011, 331, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haubner, B.J.; Schneider, J.; Schweigmann, U.; Schuetz, T.; Dichtl, W.; Velik-Salchner, C.; Stein, J.I.; Penninger, J.M. Functional Recovery of a Human Neonatal Heart After Severe Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; D’Agostino, G.; Loo, S.J.; Wang, C.X.; Su, L.P.; Tan, S.H.; Tee, G.Z.; Pua, C.J.; Pena, E.M.; Cheng, R.B.; et al. Early Regenerative Capacity in the Porcine Heart. Circulation 2018, 138, 2798–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur, A.; Lee, R.T. Mechanisms of Cardiac Regeneration. Dev. Cell 2016, 36, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Hippenmeyer, S.; Saadat, L.V.; Luo, L.; Weissman, I.L.; Ardehali, R. Existing cardiomyocytes generate cardiomyocytes at a low rate after birth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8850–8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.C.; Segers, V.F.; Davis, M.E.; MacGillivray, C.; Gannon, J.; Molkentin, J.D.; Robbins, J.; Lee, R.T. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, M.; Shah, A.M.; Tan, W.; Liu, N.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Cell-Type-Specific Gene Regulatory Networks Underlying Murine Neonatal Heart Regeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelman, S.; Liu, P.P.; Mann, D.L. Role of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in cardiac injury and repair. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saparov, A.; Ogay, V.; Nurgozhin, T.; Chen, W.C.W.; Mansurov, N.; Issabekova, A.; Zhakupova, J. Role of the immune system in cardiac tissue damage and repair following myocardial infarction. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 66, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.D.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The Biological Basis for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammation to Fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, U.; Frantz, S. Role of T-cells in myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennet, T.; Hagen, F.K.; Tabak, L.A.; Marth, J.D. T-cell-specific deletion of a polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase gene by site-directed recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 12070–12074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, N.R.; Shetye, S.S.; Bogush, I.; Keene, D.R.; Tufa, S.; Hudson, D.M.; Archer, M.; Qin, L.; Soslowsky, L.J.; Dyment, N.A.; et al. Reticulocalbin 3 is involved in postnatal tendon development by regulating collagen fibrillogenesis and cellular maturation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Anzai, A.; Katsumata, Y.; Matsuhashi, T.; Ito, K.; Endo, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Takeshima, A.; Shinmura, K.; Shen, W.; et al. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.I.; Porrello, E.R.; Kimura, W.; Olson, E.N.; Sadek, H.A. Surgical models for cardiac regeneration in neonatal mice. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.; Cheng, L.; Moon, C.; Spurgeon, H.; Lakatta, E.G.; Talan, M.I. Induction of myocardial infarcts of a predictable size and location by branch pattern probability-assisted coronary ligation in C57BL/6 mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H1201–H1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, M.L.; Kassiri, Z.; Virag, J.A.I.; de Castro Bras, L.E.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Guidelines for measuring cardiac physiology in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H733–H752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafiriou, M.P.; Noack, C.; Unsold, B.; Didie, M.; Pavlova, E.; Fischer, H.J.; Reichardt, H.M.; Bergmann, M.W.; El-Armouche, A.; Zimmermann, W.H.; et al. Erythropoietin responsive cardiomyogenic cells contribute to heart repair post myocardial infarction. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 2480–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurien, B.T.; Scofield, R.H. Western blotting. Methods 2006, 38, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, A.; Kikuchi, Y.; Sato, Y.; Koide, S.; Yuasa, K.; Nagahama, M.; Matsuda, Y. A proteomic approach reveals transient association of reticulocalbin-3, a novel member of the CREC family, with the precursor of subtilisin-like proprotein convertase, PACE4. Biochem. J. 2006, 396, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Man Lam, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, R.; Shui, G.; Ma, R.Z. Neonatal Respiratory Failure with Retarded Perinatal Lung Maturation in Mice Caused by Reticulocalbin 3 Disruption. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 54, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martinez, E.; Ibarrola, J.; Fernandez-Celis, A.; Santamaria, E.; Fernandez-Irigoyen, J.; Rossignol, P.; Jaisser, F.; Lopez-Andres, N. Differential Proteomics Identifies Reticulocalbin-3 as a Novel Negative Mediator of Collagen Production in Human Cardiac Fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.K.; Rhee, J.W.; Wu, J.C. Adult Stem Cell Therapy and Heart Failure, 2000 to 2016: A Systematic Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubner, B.J.; Adamowicz-Brice, M.; Khadayate, S.; Tiefenthaler, V.; Metzler, B.; Aitman, T.; Penninger, J.M. Complete cardiac regeneration in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Aging 2012, 4, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, E.; Zhao, M.; Chong, Z.; Fan, C.; Tang, Y.; Hunter, J.D.; Borovjagin, A.V.; Walcott, G.P.; Chen, J.Y.; et al. Regenerative Potential of Neonatal Porcine Hearts. Circulation 2018, 138, 2809–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzahor, E.; Poss, K.D. Cardiac regeneration strategies: Staying young at heart. Science 2017, 356, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, U.; Beyersdorf, N.; Weirather, J.; Podolskaya, A.; Bauersachs, J.; Ertl, G.; Kerkau, T.; Frantz, S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 2012, 125, 1652–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolejsi, T.; Delgobo, M.; Schuetz, T.; Tortola, L.; Heinze, K.G.; Hofmann, U.; Frantz, S.; Bauer, A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Penninger, J.M.; et al. Adult T-cells impair neonatal cardiac regeneration. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2698–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curato, C.; Slavic, S.; Dong, J.; Skorska, A.; Altarche-Xifro, W.; Miteva, K.; Kaschina, E.; Thiel, A.; Imboden, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Identification of noncytotoxic and IL-10-producing CD8+AT2R+ T cell population in response to ischemic heart injury. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 6286–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varda-Bloom, N.; Leor, J.; Ohad, D.G.; Hasin, Y.; Amar, M.; Fixler, R.; Battler, A.; Eldar, M.; Hasin, D. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes are activated following myocardial infarction and can recognize and kill healthy myocytes in vitro. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2000, 32, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nomura, T.; Ono, M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 2008, 133, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaczewski, M.; Xia, Y.; Bujak, M.; Gonzalez-Quesada, C.; Frangogiannis, N.G. CCR5 signaling suppresses inflammation and reduces adverse remodeling of the infarcted heart, mediating recruitment of regulatory T cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirather, J.; Hofmann, U.D.; Beyersdorf, N.; Ramos, G.C.; Vogel, B.; Frey, A.; Ertl, G.; Kerkau, T.; Frantz, S. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchigna, S.; Martinelli, V.; Moimas, S.; Colliva, A.; Anzini, M.; Nordio, A.; Costa, A.; Rehman, M.; Vodret, S.; Pierro, C.; et al. Paracrine effect of regulatory T cells promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation during pregnancy and after myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroudgar, S.; Thuerauf, D.J.; Marcinko, M.C.; Belmont, P.J.; Glembotski, C.C. Ischemia activates the ATF6 branch of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 29735–29745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroudgar, S.; Glembotski, C.C. New concepts of endoplasmic reticulum function in the heart: Programmed to conserve. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2013, 55, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendyk, J.; Sreenivasaiah, P.K.; Kim, D.H.; Agellon, L.B.; Michalak, M. Biology of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Nguyen, C.; May, H.I.; Li, X.; Al-Hashimi, A.A.; Austin, R.C.; Gillette, T.G.; Fu, G.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Chaperone GRP78 Protects Heart From Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury Through Akt Activation. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitadello, M.; Penzo, D.; Petronilli, V.; Michieli, G.; Gomirato, S.; Menabo, R.; Di Lisa, F.; Gorza, L. Overexpression of the stress protein Grp94 reduces cardiomyocyte necrosis due to calcium overload and simulated ischemia. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 923–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.C.; Knobel, J.; Burkert-Rettenmaier, S.; Li, X.; Meyer, I.S.; Jungmann, A.; Sicklinger, F.; Backs, J.; Lasitschka, F.; Muller, O.J.; et al. Secretome Analysis of Cardiomyocytes Identifies PCSK6 (Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 6) as a Novel Player in Cardiac Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2020, 141, 1628–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kino, T.; Mohsin, S.; Chiba, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Ishigami, T. Neonatal Regulatory T Cells Mediate Fibrosis and Contribute to Cardiac Repair. Cells 2026, 15, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020204

Kino T, Mohsin S, Chiba Y, Sugiyama M, Ishigami T. Neonatal Regulatory T Cells Mediate Fibrosis and Contribute to Cardiac Repair. Cells. 2026; 15(2):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020204

Chicago/Turabian StyleKino, Tabito, Sadia Mohsin, Yumi Chiba, Michiko Sugiyama, and Tomoaki Ishigami. 2026. "Neonatal Regulatory T Cells Mediate Fibrosis and Contribute to Cardiac Repair" Cells 15, no. 2: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020204

APA StyleKino, T., Mohsin, S., Chiba, Y., Sugiyama, M., & Ishigami, T. (2026). Neonatal Regulatory T Cells Mediate Fibrosis and Contribute to Cardiac Repair. Cells, 15(2), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020204