Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 Enhances Lung Endothelial Cell Homeostasis Under Shear Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Electrical Cell–Substrate Impedance Sensing

2.4. Expression Permeability Test Assay

2.5. Western Blot

2.6. qPCR

2.7. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.8. Shear Stress

2.9. Immunofluorescence

2.10. siRNA Transfection

2.11. Fluorescence Intensity

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. ADM Improves Endothelial Barrier Function

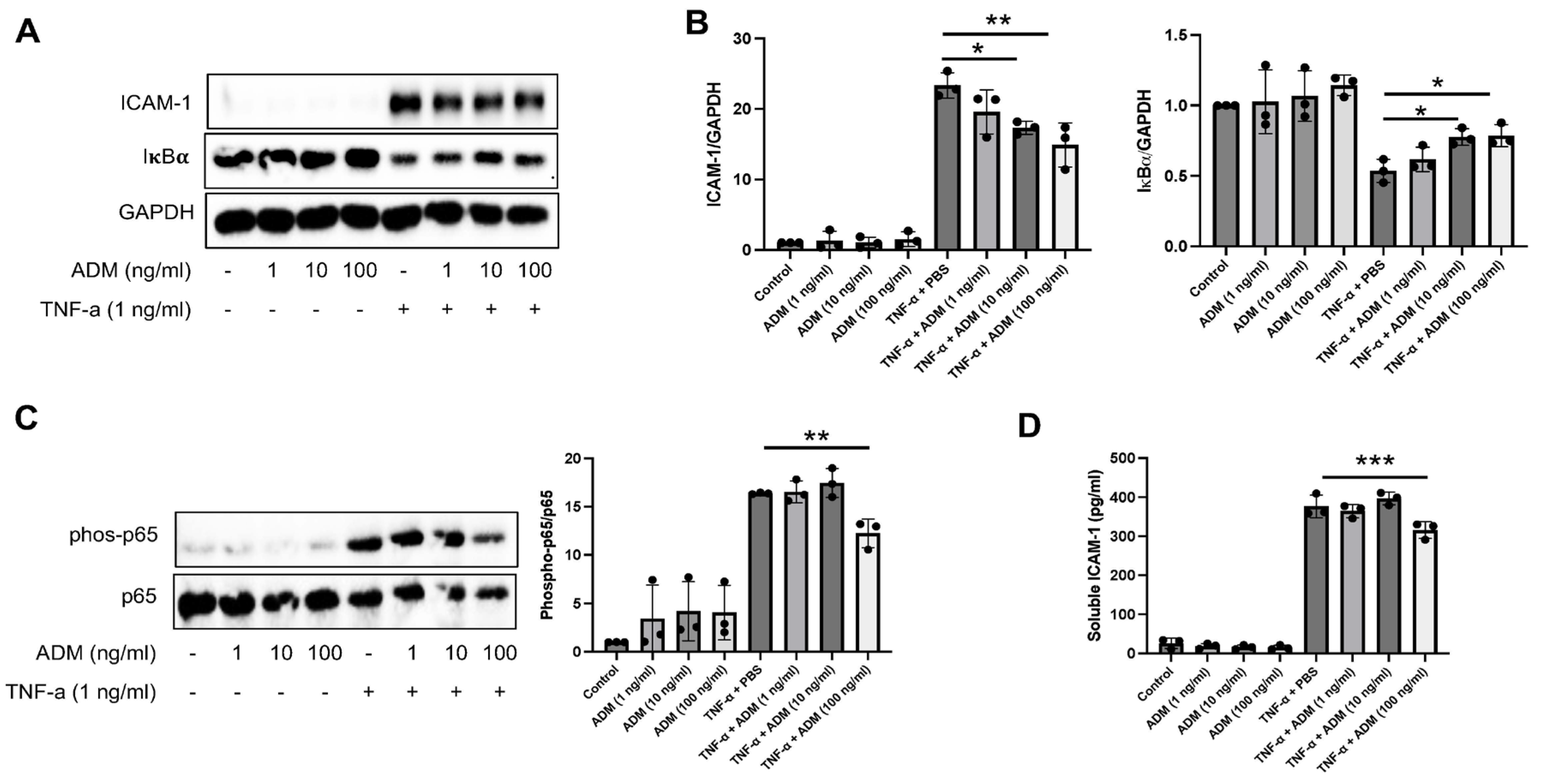

3.2. ADM Reduces Inflammatory Responses

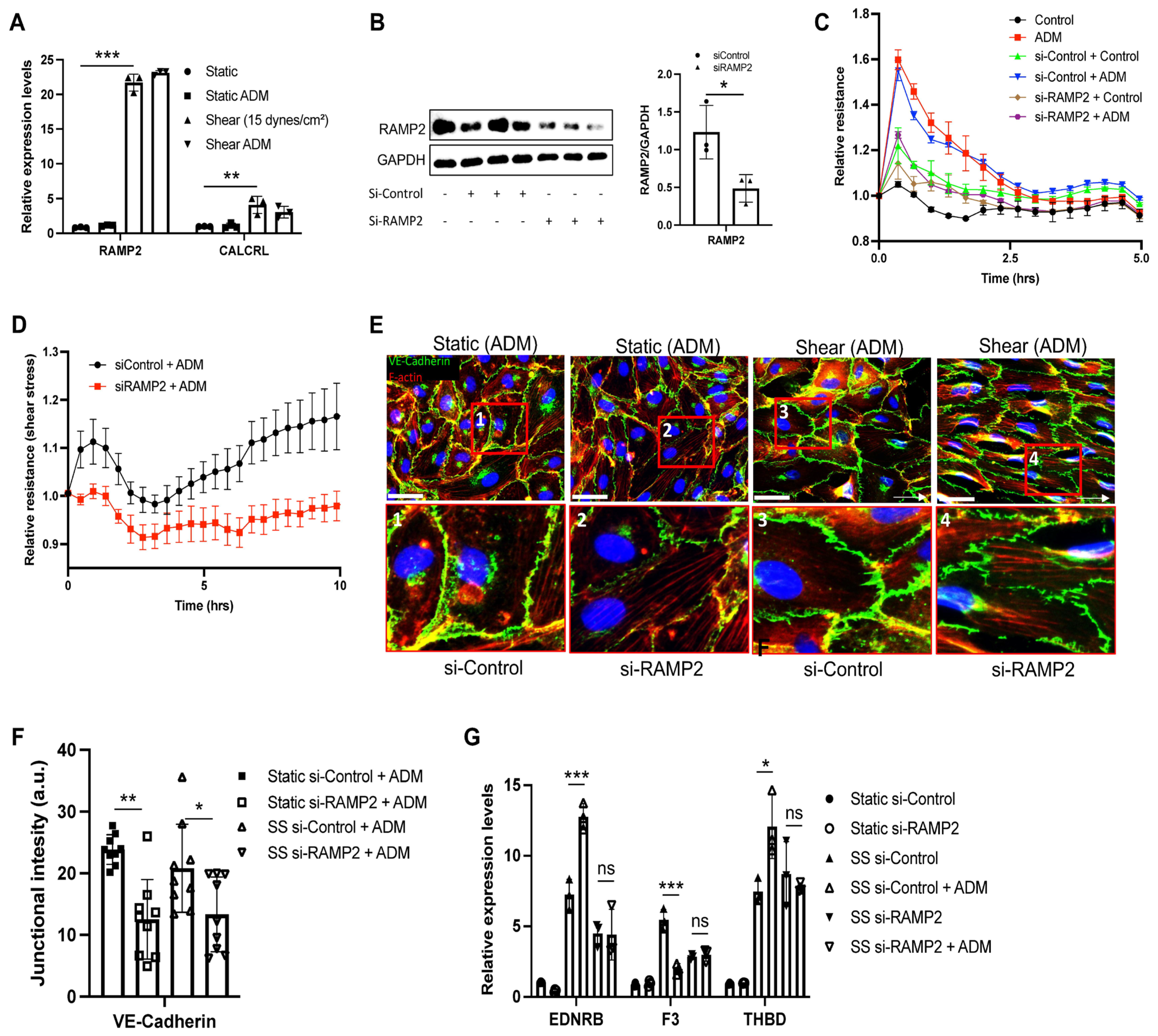

3.3. ADM Improves Endothelial Homeostatic Markers Under Shear Stress

3.4. ADM Regulates Endothelial Cell Functions Through an RAMP2-Dependent Mechanism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ejikeme, C.; Safdar, Z. Exploring the pathogenesis of pulmonary vascular disease. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1402639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, A.; Guignabert, C.; Barberà, J.A.; Bärtsch, P.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Dewachter, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Dorfmüller, P.; et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelium: The orchestra conductor in respiratory diseases: Highlights from basic research to therapy. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1700745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, A.; Fang, Z.; Sakurai, Y.; Choi, H.; Williams, E.K.; Hardy, E.T.; Maher, K.; Coskun, A.F.; et al. Clinically relevant clot resolution via a thromboinflammation-on-a-chip. Nature 2025, 641, 1298–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Ahn, B.; Sakurai, Y.; Hansen, C.E.; Tran, R.; Mimche, P.N.; Mannino, R.G.; Ciciliano, J.C.; Lamb, T.J.; Joiner, C.H.; et al. Microvasculature-on-a-chip for the long-term study of endothelial barrier dysfunction and microvascular obstruction in disease. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.A.; Leopoldi, A.; Aichinger, M.; Wick, N.; Hantusch, B.; Novatchkova, M.; Taubenschmid, J.; Hämmerle, M.; Esk, C.; Bagley, J.A.; et al. Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature 2019, 565, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Pek, N.M.; Tan, C.; Jiang, C.; Yu, Z.; Iwasawa, K.; Shi, M.; Kechele, D.O.; Sundaram, N.; Pastrana-Gomez, V.; et al. Co-development of mesoderm and endoderm enables organotypic vascularization in lung and gut organoids. Cell 2025, 188, 4295–4313 e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettschureck, N.; Strilic, B.; Offermanns, S. Passing the Vascular Barrier: Endothelial Signaling Processes Controlling Extravasation. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1467–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, J.C.; Adams, T.S.; Cosme, C., Jr.; Raredon, M.S.B.; Yuan, Y.; Omote, N.; Poli, S.; Chioccioli, M.; Rose, K.-A.; Manning, E.P.; et al. Integrated Single-Cell Atlas of Endothelial Cells of the Human Lung. Circulation 2021, 144, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.F. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2009, 6, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintard, C.; Tubbs, E.; Jonsson, G.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Werschler, N.; Laporte, C.; Pitaval, A.; Bah, T.-S.; Pomeranz, G.; et al. A microfluidic platform integrating functional vascularized organoids-on-chip. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.E.; Pinals, R.L.; Choi, A.; Truong, N.; Kang, E.; Jiang, A.; Lozano Cruz, C.F.; Hawkins, S.; Sarcar, R.; Volkova, A.; et al. Vascular-Perfusable Human 3D Brain-on-Chip. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeyens, N.; Nicoli, S.; Coon, B.G.; Ross, T.D.; Dries, K.V.D.; Han, J.; Lauridsen, H.M.; Mejean, C.O.; Eichmann, A.; Thomas, J.-L.; et al. Vascular remodeling is governed by a VEGFR3-dependent fluid shear stress set point. Elife 2015, 4, e04645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.K.; Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y. Biophysical and Biochemical Roles of Shear Stress on Endothelium: A Revisit and New Insights. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 752–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birukova, A.A.; Shah, A.S.; Tian, Y.; Moldobaeva, N.; Birukov, K.G. Dual role of vinculin in barrier-disruptive and barrier-enhancing endothelial cell responses. Cell Signal 2016, 28, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasain, N.; Stevens, T. The actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 77, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Leiby, K.L.; Greaney, A.M.; Raredon, M.S.B.; Qian, H.; Schupp, J.C.; Engler, A.J.; Baevova, P.; Adams, T.S.; Kural, M.H.; et al. A Pulmonary Vascular Model From Endothelialized Whole Organ Scaffolds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 760309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillich, A.; Zhang, F.; Farmer, C.G.; Travaglini, K.J.; Tan, S.Y.; Gu, M.; Zhou, B.; Feinstein, J.A.; Krasnow, M.A.; Metzger, R.J. Capillary cell-type specialization in the alveolus. Nature 2020, 586, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.C.; Witzenrath, M.; Tschernig, T.; Gutbier, B.; Hippenstiel, S.; Santel, A.; Suttorp, N.; Rosseau, S. Adrenomedullin attenuates ventilator-induced lung injury in mice. Thorax 2010, 65, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutbier, B.; Neuhauß, A.-K.; Reppe, K.; Ehrler, C.; Santel, A.; Kaufmann, J.; Scholz, M.; Weissmann, N.; Morawietz, L.; Mitchell, T.J.; et al. Prognostic and Pathogenic Role of Angiopoietin-1 and -2 in Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippenstiel, S.; Witzenrath, M.; Schmeck, B.; Hocke, A.; Krisp, M.; Krull, M.; Seybold, J.; Seeger, W.; Rascher, W.; Schutte, H.; et al. Adrenomedullin reduces endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.S.; Chien, S. Shear stress-initiated signaling and its regulation of endothelial function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Shih, Y.T.; Wei, S.Y.; Chiu, J.J. Impacts of aging and fluid shear stress on vascular endothelial metabolism and atherosclerosis development. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traub, O.; Berk, B.C. Laminar shear stress: Mechanisms by which endothelial cells transduce an atheroprotective force. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, K.M.; Larman, H.B.; Dai, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, E.T.; Moorthy, S.N.; Kratz, J.R.; Lin, Z.; Jain, M.K.; Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; et al. Integration of flow-dependent endothelial phenotypes by Kruppel-like factor 2. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Pan, H.; Guo, X.; Huang, Y.; Luo, J.Y. Endothelial Kruppel-like factor 2/4: Regulation and function in cardiovascular diseases. Cell. Signal. 2025, 130, 111699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahmann, N.; Woods, A.; Spengler, K.; Heslegrave, A.; Bauer, R.; Krause, S.; Viollet, B.; Carling, D.; Heller, R. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by vascular endothelial growth factor mediates endothelial angiogenesis independently of nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 10638–10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lee, T.-S.; Kolb, E.M.; Sun, K.; Lu, X.; Sladek, F.M.; Kassab, G.S.; Garland, T., Jr.; Shyy, J.Y.-J. AMP-activated protein kinase is involved in endothelial NO synthase activation in response to shear stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bi, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.X.; Chiu, J.-J.; Liu, G.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, P.; Jiang, F. Shear stress regulates endothelial cell autophagy via redox regulation and Sirt1 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.E.; Cai, H.; Drummond, G.R.; Harrison, D.G. Shear stress regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression through c-Src by divergent signaling pathways. Circ. Res. 2001, 89, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Riha, G.M.; Yan, S.; Li, M.; Chai, H.; Yang, H.; Yao, Q.; Chen, C. Shear stress induces endothelial differentiation from a murine embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell line. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 1817–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Takahashi, T.; Asahara, T.; Ohura, N.; Sokabe, T.; Kamiya, A.; Ando, J. Proliferation, differentiation, and tube formation by endothelial progenitor cells in response to shear stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iring, A.; Jin, Y.-J.; Albarrán-Juárez, J.; Siragusa, M.; Wang, S.; Dancs, P.T.; Nakayama, A.; Tonack, S.; Chen, M.; Künne, C.; et al. Shear stress-induced endothelial adrenomedullin signaling regulates vascular tone and blood pressure. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2775–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, A.; Albarrán-Juárez, J.; Liang, G.; Roquid, K.A.; Iring, A.; Tonack, S.; Chen, M.; Müller, O.J.; Weinstein, L.S.; Offermanns, S. Disturbed flow-induced Gs-mediated signaling protects against endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis. JCI J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 5, e140485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, F.; Kinasewitz, G.; Dormer, K. The role of endothelial shear stress on haemodynamics, inflammation, coagulation and glycocalyx during sepsis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 12258–12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbrandt, E.B.; Reade, M.C.; Lee, M.; Shook, S.L.; Angus, D.C.; Kong, L.; Carter, M.; Yealy, D.M.; Kellum, J.A. Prevalence and significance of coagulation abnormalities in community-acquired pneumonia. Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullivan, S.; Murphy, C.A.; Weiss, L.; Comer, S.P.; Kevane, B.; McCullagh, B.; Maguire, P.B.; Ainle, F.N.; Gaine, S.P. Platelets, extracellular vesicles and coagulation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2021, 11, 20458940211021036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernysh, I.N.; Nagaswami, C.; Kosolapova, S.; Peshkova, A.D.; Cuker, A.; Cines, D.B.; Cambor, C.L.; Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. The distinctive structure and composition of arterial and venous thrombi and pulmonary emboli. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casa, L.D.; Deaton, D.H.; Ku, D.N. Role of high shear rate in thrombosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikezoe, T. Thrombomodulin/activated protein C system in septic disseminated intravascular coagulation. J. Intensive Care 2015, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochfort, K.D.; Cummins, P.M. Thrombomodulin regulation in human brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro: Role of cytokines and shear stress. Microvasc. Res. 2015, 97, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, V.; Houssaye, S.; Ternisien, C.; Leon, A.; De Verneuil, H.; Elbim, C.; Mackman, N.; Edgington, T.S.; De Prost, D. Endotoxin-induced tissue factor messenger RNA in human monocytes is negatively regulated by a cyclic AMP-dependent mechanism. Blood 1993, 81, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler-Guettler, H.; Yu, K.; Soff, G.; Gudas, L.J.; Rosenberg, R.D. Thrombomodulin gene regulation by cAMP and retinoic acid in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 2155–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, A.E.; Cundiff, D.L.; Soff, G.A. cAMP influence on transcription of thrombomodulin is dependent on de novo synthesis of a protein intermediate: Evidence for cohesive regulation of myogenic proteins in vascular smooth muscle. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1995, 126, 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa, K.; Aoki, N. Regulatory mechanisms for thrombomodulin expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro. J. Cell Physiol. 1991, 147, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archipoff, G.; Beretz, A.; Bartha, K.; Brisson, C.; de la Salle, C.; Froget-Léon, C.; Klein-Soyer, C.; Cazenave, J. Role of cyclic AMP in promoting the thromboresistance of human endothelial cells by enhancing thrombomodulin and decreasing tissue factor activities. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 109, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fato, B.R.; Beard, S.; Binder, N.K.; Pritchard, N.; Kaitu’u-Lino, T.J.; de Alwis, N.; Hannan, N.J. The Regulation of Endothelin-1 in Pregnancies Complicated by Gestational Diabetes: Uncovering the Vascular Effects of Insulin. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dschietzig, T.; Richter, C.; Asswad, L.; Baumann, G.; Stangl, K. Hypoxic induction of receptor activity-modifying protein 2 alters regulation of pulmonary endothelin-1 by adrenomedullin: Induction under normoxia versus inhibition under hypoxia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 321, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Sequence (5-3) | Size | NCBI Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLF2 | Forward | ACTTTCGCCAGCCCGTGC | 103 | NM_016270.4 |

| Reverse | AGTCCAGCACGCTGTTGAG | |||

| KLF4 | Forward | CTGCGGCAAAACCTACACAA | 182 | NM_001314052.2 |

| Reverse | GGTCGCATTTTTGGCACTG | |||

| CD31 | Forward | CCAGTGTCCCCAGAAGCAAA | 81 | NM_000442.5 |

| Reverse | TGATAACCACTGCAATAAGTCCTTTC | |||

| CDH5 | Forward | TTGGAACCAGATGCACATTGAT | 86 | NM_001795.5 |

| Reverse | TCTTGCGACTCACGCTTGAC | |||

| NOS3 | Forward | GCCGGAACAGCACAAGAGTTAT | 150 | NM_000603.5 |

| Reverse | AGCCCGAACACACAGAACC | |||

| KDR | Forward | CGGTCAACAAAGTCGGGAGA | 123 | NM_002253.4 |

| Reverse | CAGTGCACCACAAAGACACG | |||

| TEK | Forward | GATTTTGGATTGTCCCGAGGTCAAG | 327 | NM_000459.5 |

| Reverse | CACCAATATCTGGGCAAATGATGG | |||

| ANGPT1 | Forward | TGGCTGCAAAAACTTGAGAATTAC | 145 | NM_001146.5 |

| Reverse | TTCTGGTCTGCTCTGCAGTCTG | |||

| S1PR1 | Forward | TGCGGGAAGGGAGTATGTTT | 198 | NM_001400.5 |

| Reverse | TGCAGTTCCAGCCCATGATA | |||

| F3 | Forward | CAGACAGCCCGGTAGAGTGT | 75 | NM_001993.5 |

| Reverse | CCACAGCTCCAATGATGTAGAA | |||

| PROCR | Forward | ACTTCTCTTTTCCCTAGACTGC | 169 | NM_006404.5 |

| Reverse | TGAAGTCTTTGGAGGCCATCT | |||

| CD36 | Forward | ACTGAGGACTGCAGTGTAGG | 223 | NM_001001548.3 |

| Reverse | GGTTTCTACAAGCTCTGGTTCTTA | |||

| EDNRB | Forward | CTGGCCATTTGGAGCTGAGA | 200 | NM_000115.5 |

| Reverse | CCAGAACCACAGAGACCACC | |||

| HPGD | Forward | CATGCACGTGAACGGCAAAG | 155 | NM_000860.6 |

| Reverse | GCTCATCCAGGGCAGCTTTA | |||

| SOX17 | Forward | AAGGGCGAGTCCCGTATC | 221 | NM_022454.4 |

| Reverse | TTGTAGTTGGGGTGGTCCTG | |||

| ACKR1 | Forward | GATGGCCTCCTCTGGGTATG | 198 | NM_001122951.3 |

| Reverse | AAGGGCAGTGCAGAGTCATC | |||

| RAMP2 | Forward | CTGTCCTGAATCCCCACGAG | 191 | NM_005854.3 |

| Reverse | CAGGGTGCTATAAGGCCTGC | |||

| CALCRL | Forward | AAGAGCTGGACTGGGTCTTGA | 212 | NM_005795.6 |

| Reverse | GAAGTTTGCAGCAGTCTTGTCA | |||

| THBD | Forward | CCCAACACCCAGGCTAGCT | 76 | NM_000361.3 |

| Reverse | CGTCGATGTCCGTGCAGAT | |||

| GAPDH | Forward | ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTC | 108 | NM_002046.7 |

| Reverse | GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA | |||

| IL1B | Forward | CAGGCTGCTCTGGGATTCTC | 172 | NM_000576.3 |

| Reverse | GTCCTGGAAGGAGCACTTCAT | |||

| IL6 | Forward | ACTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG | 149 | NM_000600.5 |

| Reverse | CCATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG | |||

| ICAM1 | Forward | ACCATCTACAGCTTTCCGGC | 293 | NM_000201.3 |

| Reverse | CAATCCCTCTCGTCCAGTCG | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoon, Y.; Duffy, S.R.; Kirk, S.E.; Promnares, K.; Karki, P.; Birukova, A.A.; Birukov, K.G.; Yuan, Y. Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 Enhances Lung Endothelial Cell Homeostasis Under Shear Stress. Cells 2026, 15, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020152

Yoon Y, Duffy SR, Kirk SE, Promnares K, Karki P, Birukova AA, Birukov KG, Yuan Y. Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 Enhances Lung Endothelial Cell Homeostasis Under Shear Stress. Cells. 2026; 15(2):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020152

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Yongdae, Sean R. Duffy, Shannon E. Kirk, Kamoltip Promnares, Pratap Karki, Anna A. Birukova, Konstantin G. Birukov, and Yifan Yuan. 2026. "Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 Enhances Lung Endothelial Cell Homeostasis Under Shear Stress" Cells 15, no. 2: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020152

APA StyleYoon, Y., Duffy, S. R., Kirk, S. E., Promnares, K., Karki, P., Birukova, A. A., Birukov, K. G., & Yuan, Y. (2026). Adrenomedullin-RAMP2 Enhances Lung Endothelial Cell Homeostasis Under Shear Stress. Cells, 15(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020152