Network Hypoactivity in ALG13-CDG: Disrupted Developmental Pathways and E/I Imbalance as Early Drivers of Neurological Features in CDG

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. X Inactivation Skewing

2.3. Organoid Lysis and Protein Digestion

2.4. Tissue Preparation, Processing, and Analysis for MALDI-MSI

2.5. Single Cell Suspension Formation, Library Preparation, and Sequencing for scRNAseq

2.6. scRNAseq Data Analysis

2.7. CellChat Analysis

2.8. Organoid Preparation and Metabolite Measurement for Metabolomics

2.9. Lipid Extraction from Organoids

2.10. LC-MS/MS Analysis of Lipids

2.11. Data Analysis for Lipidomics

2.12. Plating of cBOs on Multi-Electrode Array (MEA) and Activity, Network, and Axon Recording

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort

3.2. X-Inactivation Skewing in ALG13-CDG

3.3. Proteomic Analysis of ALG13-CDG hCOs

3.4. ALG13-CDG hCOs Exhibit Distinct N-Glycosylation Remodeling

3.5. N-Glycomic Analysis Reveals Distinct Differences in ALG13-CDG hCOs

3.6. Cell Type-Specific Transcriptional Alterations Highlight Disrupted Neurodevelopmental Pathways in ALG13-CDG hCOs

3.7. Metabolic Analysis Reveals Limited Alterations in ALG13-CDG hCOs

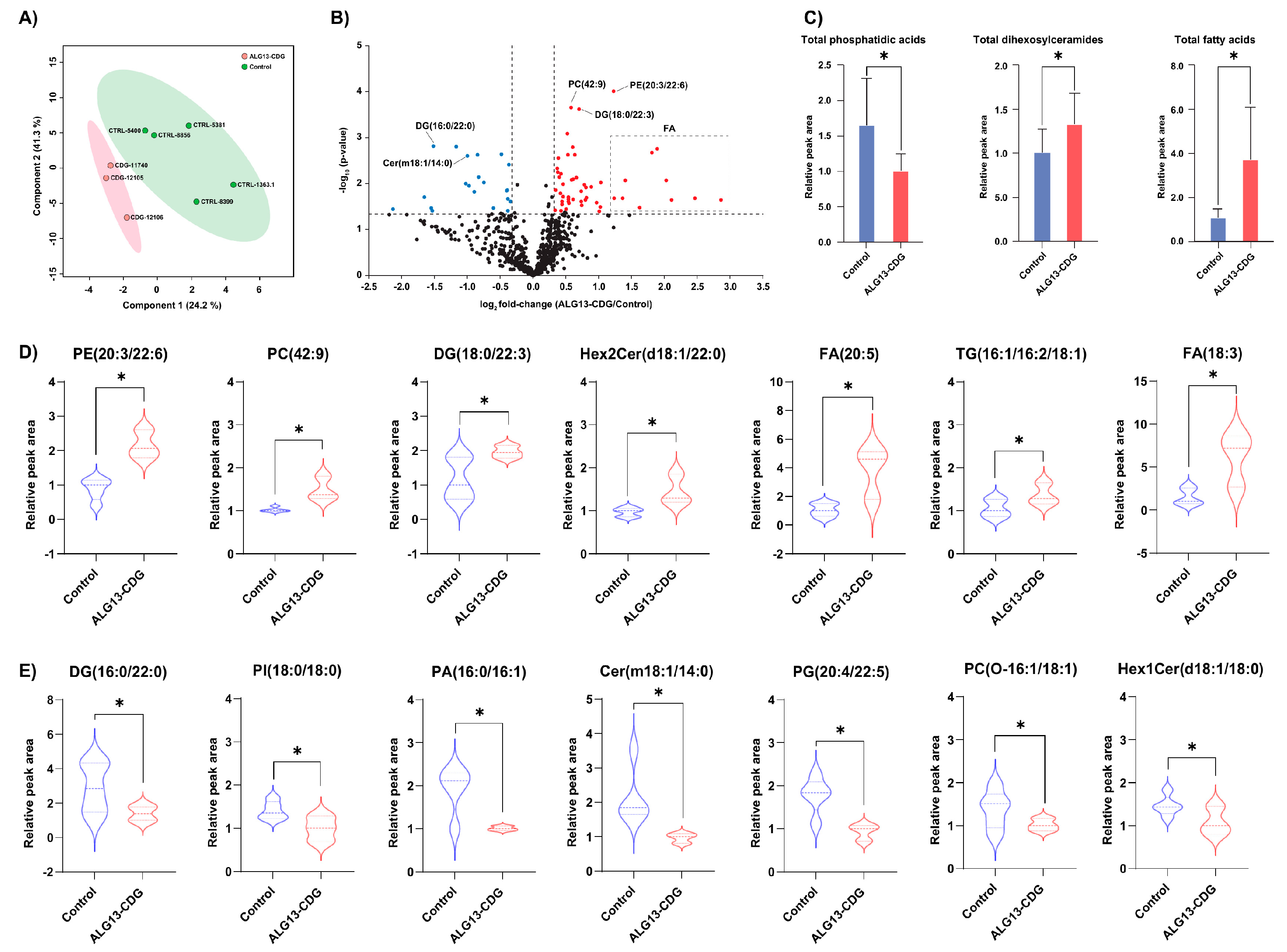

3.8. Lipidomic Profiling Identifies Broad Alterations in Phospholipid Composition in ALG13-CDG hCOs

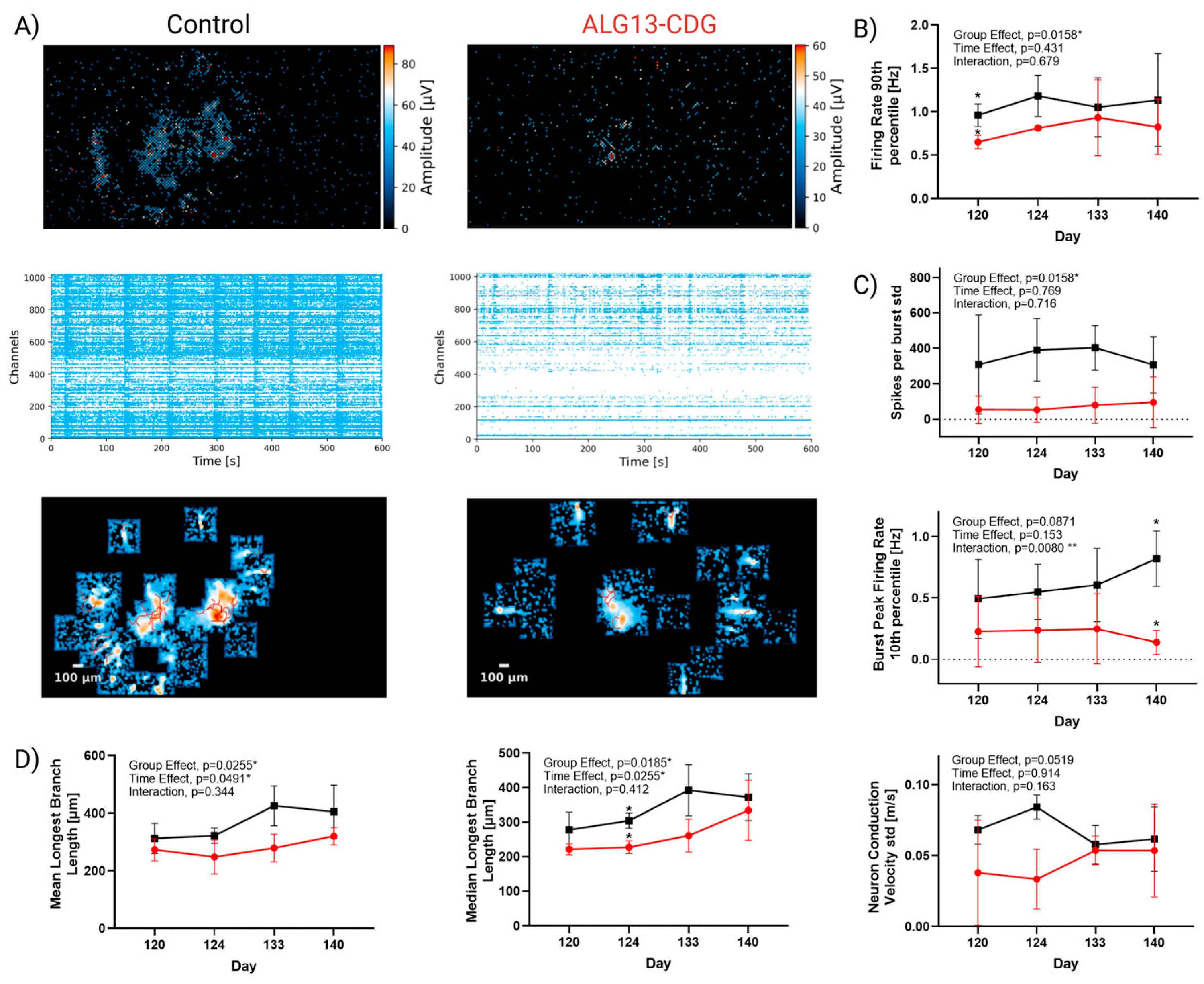

3.9. ALG13-CDG Cortical Organoids Exhibit Reduced Activity and Impaired Neuronal Network Maturation and Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. X-Inactivation Skewing in ALG13-CDG

4.2. ECM Dysregulation Contributes to Neurodevelopmental Defects in ALG13-CDG

4.3. ER Stress-Driven Oxidative Dysregulation in ALG13-CDG

4.4. Calcium-Signaling Abnormalities Contribute to Neurological Pathology in ALG13-CDG

4.5. Lipid and Metabolic Disruption Aligns with Proteomic and Transcriptomic Defects in ALG13-CDG

4.6. Network-Level Vulnerability and Excitatory/Inhibitory Imbalance in ALG13-CDG

4.7. Paradoxical Hypoactivity Reveals Latent Hyperexcitability and Disrupted E/I Maturation in ALG13-CDG

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Weixel, T.; Wolfe, L.; Macnamara, E.F. Genetic counseling for congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG). J. Genet. Couns. 2024, 33, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lam, C.; Scaglia, F.; Berry, G.T.; Larson, A.; Sarafoglou, K.; Andersson, H.C.; Sklirou, E.; Tan, Q.K.G.; Starosta, R.T.; Sadek, M.; et al. Frontiers in congenital disorders of glycosylation consortium, a cross-sectional study report at year 5 of 280 individuals in the natural history cohort. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 142, 108509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharhan, H.; He, M.; Edmondson, A.C.; Daniel, E.J.P.; Chen, J.; Donald, T.; Bakhtiari, S.; Amor, D.J.; Jones, E.A.; Vassallo, G.; et al. ALG13 X-linked intellectual disability: New variants, glycosylation analysis, and expanded phenotypes. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 44, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Johnsen, C.; Pletcher, B.A.; Edmondson, A.C.; Kozicz, T.; Morava, E. Long-term outcomes in ALG13-Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2023, 191, 1626–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Eklund, E.A.; Radenkovic, S.; Sadek, M.; Shammas, I.; Verberkmoes, S.; Ng, B.G.; Freeze, H.H.; Edmondson, A.C.; He, M.; et al. ALG13-Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation (ALG13-CDG): Updated clinical and molecular review and clinical management guidelines. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2024, 142, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.G.; Eklund, E.A.; Shiryaev, S.A.; Dong, Y.Y.; Abbott, M.A.; Asteggiano, C.; Bamshad, M.J.; Barr, E.; Bernstein, J.A.; Chelakkadan, S.; et al. Predominant and novel de novo variants in 29 individuals with ALG13 deficiency: Clinical description, biomarker status, biochemical analysis, and treatment suggestions. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 1333–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galama, W.H.; Verhaagen-van den Akker, S.L.J.; Lefeber, D.J.; Feenstra, I.; Verrips, A. ALG13-CDG with Infantile Spasms in a Male Patient Due to a De Novo ALG13 Gene Mutation. JIMD Rep. 2018, 40, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.D.; Xu, S.; Chen, S.; Chen, Z.H.; Dean, N.; Wang, N.; Gao, X.D. An in vitro assay for enzymatic studies on human ALG13/14 heterodimeric UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.P.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Fang, W.; Wang, Z.; Ye, H.; Wang, M.J.; Ke, L.; Huang, T.; Lv, P.; et al. Lipid-accumulated reactive astrocytes promote disease progression in epilepsy. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radenkovic, S.; Budhraja, R.; Klein-Gunnewiek, T.; King, A.T.; Bhatia, T.N.; Ligezka, A.N.; Driesen, K.; Shah, R.; Ghesquiere, B.; Pandey, A.; et al. Neural and metabolic dysregulation in PMM2-deficient human in vitro neural models. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.C.; Zoghbi, H.Y.; Moseley, A.B.; Rosenblatt, H.M.; Belmont, J.W. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992, 51, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, S.A.; Andersen, J.; Pasca, A.M.; Birey, F.; Pasca, S.P. Generation and assembly of human brain region-specific three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 2062–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R.R.; Powers, T.W.; Norris-Caneda, K.; Mehta, A.S.; Angel, P.M. In Situ Imaging of N-Glycans by MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry of Fresh or Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2018, 94, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Gao, R.; Negraes, P.D.; Gu, J.; Buchanan, J.; Preissl, S.; Wang, A.; Wu, W.; Haddad, G.G.; Chaim, I.A.; et al. Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 558–569.E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garma, L.; Harder, L.; Barba-Reyes, J.; Diez-Salguero, M.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Hyman, B.; Munoz-Manchado, A. Interneuron diversity in the human dorsal striatum. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ding, P.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F. Integrative cross-species analysis of GABAergic neuron cell types and their functions in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Lu, Q. Molecular divergence of mammalian astrocyte progenitor cells at early gliogenesis. Development 2022, 149, dev199985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Love, M.I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: Removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Cacchiarelli, D.; Grimsby, J.; Pokharel, P.; Li, S.; Morse, M.; Lennon, N.J.; Livak, K.J.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Rinn, J.L. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Chang, I.; Ramos, R.; Kuan, C.H.; Myung, P.; Plikus, M.V.; Nie, Q. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radenkovic, S.; Fitzpatrick-Schmidt, T.; Byeon, S.K.; Madugundu, A.K.; Saraswat, M.; Lichty, A.; Wong, S.Y.W.; McGee, S.; Kubiak, K.; Ligezka, A.; et al. Expanding the clinical and metabolic phenotype of DPM2 deficient congenital disorders of glycosylation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2021, 132, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.R.; Huttner, W.B. How the extracellular matrix shapes neural development. Open Biol. 2019, 9, 180216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Patel, V.N.; Song, X.; Xu, Y.; Kaminski, A.M.; Doan, V.U.; Su, G.; Liao, Y.; Mah, D.; Zhang, F.; et al. Increased 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with genetic risk gene HS3ST1. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawistowski, J.S.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Lee, M.F.; Golemis, E.A.; Marchuk, D.A. KRIT1 association with the integrin-binding protein ICAP-1: A new direction in the elucidation of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1) pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroef, V.; Ruegenberg, S.; Horn, M.; Allmeroth, K.; Ebert, L.; Bozkus, S.; Miethe, S.; Elling, U.; Schermer, B.; Baumann, U.; et al. GFPT2/GFAT2 and AMDHD2 act in tandem to control the hexosamine pathway. Elife 2022, 11, e69223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Montes, L.; Ovchinnikova, S.; Yuan, X.; Studer, T.; Sarropoulos, I.; Anders, S.; Kaessmann, H.; Cardoso-Moreira, M. Sex-biased gene expression across mammalian organ development and evolution. Science 2023, 382, eadf1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossola, C.; Kalebic, N. Roots of the Malformations of Cortical Development in the Cell Biology of Neural Progenitor Cells. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 817218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchsbaum, I.Y.; Cappello, S. Neuronal migration in the CNS during development and disease: Insights from in vivo and in vitro models. Development 2019, 146, dev163766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kular, J.K.; Basu, S.; Sharma, R.I. The extracellular matrix: Structure, composition, age-related differences, tools for analysis and applications for tissue engineering. J. Tissue Eng. 2014, 5, 2041731414557112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, M.L.; Nur-e-Kamal, A.; Liu, H.Y.; Gross, S.R.; Movahed, R.; Meiners, S. Neurite outgrowth by the alternatively spliced region of human tenascin-C is mediated by neuronal alpha7beta1 integrin. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo, A.; Tamburini, C.; Noakes, Z.; de la Fuente, D.C.; Keefe, F.; Petter, O.; Plumbly, W.; Clifton, N.E.; Li, M.; Peall, K.J. Cortical neuronal hyperexcitability and synaptic changes in SGCE mutation-positive myoclonus dystonia. Brain 2023, 146, 1523–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysko, J.; Maciag, F.; Mertens, A.; Guler, B.E.; Linnert, J.; Boldt, K.; Ueffing, M.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Heine, M.; Wolfrum, U. The Adhesion GPCR VLGR1/ADGRV1 Regulates the Ca2+ Homeostasis at Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes. Cells 2022, 11, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Qin, N.; Pi, J.; Sun, P.; Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Gao, Q.; et al. Antagonizing apolipoprotein J chaperone promotes proteasomal degradation of mTOR and relieves hepatic lipid deposition. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaric, T.S.; Gudelj, I.; Santpere, G.; Novokmet, M.; Vuckovic, F.; Ma, S.; Doll, H.M.; Risgaard, R.; Bathla, S.; Karger, A.; et al. Human-specific features and developmental dynamics of the brain N-glycome. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radenkovic, S.; Ligezka, A.N.; Mokashi, S.S.; Driesen, K.; Dukes-Rimsky, L.; Preston, G.; Owuocha, L.F.; Sabbagh, L.; Mousa, J.; Lam, C.; et al. Tracer metabolomics reveals the role of aldose reductase in glycosylation. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamici, S.; Bastaki, F.; Khalifa, M. Exome sequence identified a c.320A > G ALG13 variant in a female with infantile epileptic encephalopathy with normal glycosylation and random X inactivation: Review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 60, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.M.; Broekaart, D.W.M.; Bongaarts, A.; Muhlebner, A.; Mills, J.D.; van Vliet, E.A.; Aronica, E. Altered Extracellular Matrix as an Alternative Risk Factor for Epileptogenicity in Brain Tumors. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haushalter, C.; Asselin, L.; Fraulob, V.; Dolle, P.; Rhinn, M. Retinoic acid controls early neurogenesis in the developing mouse cerebral cortex. Dev. Biol. 2017, 430, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.S.; Kaufman, R.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cell fate decision and human disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 21, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.L.; Cobb, J.; Agarwal, R.; Maddux, M.; Cooke, M.S. How Robust is the Evidence for a Role of Oxidative Stress in Autism Spectrum Disorders and Intellectual Disabilities? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 1428–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, M.; Jurajda, M.; Duris, K. Oxidative Stress in the Brain: Basic Concepts and Treatment Strategies in Stroke. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, F.; Alfi, G.; Cetani, F.; Matrone, A.; Mazoni, L.; Apicella, M.; Pardi, E.; Borsari, S.; Laurino, M.; Lai, E.; et al. Serum calcium levels are associated with cognitive function in hypoparathyroidism: A neuropsychological and biochemical study in an Italian cohort of patients with chronic post-surgical hypoparathyroidism. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2022, 45, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqueze-Pouey, B.; Mailfert, S.; Rouger, V.; Goaillard, J.M.; Marguet, D. Physiological epidermal growth factor concentrations activate high affinity receptors to elicit calcium oscillations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.D.; Papp, K.M.; Casey, G.A.; Radziwon, A.; St Laurent, C.D.; Doucette, L.P.; MacDonald, I.M. PEX6 Mutations in Peroxisomal Biogenesis Disorders: An Usher Syndrome Mimic. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2021, 1, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Balram, A.; Li, W. Convergence: Lactosylceramide-Centric Signaling Pathways Induce Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Other Phenotypic Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanguy, E.; Wang, Q.; Moine, H.; Vitale, N. Phosphatidic Acid: From Pleiotropic Functions to Neuronal Pathology. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafstrom, C.E. Epilepsy: A review of selected clinical syndromes and advances in basic science. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2006, 26, 983–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Tang, Y.S.; Chen, B.; Xu, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.C.; Zhao, H.W.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, Z. Early hypoactivity of hippocampal rhythms during epileptogenesis after prolonged febrile seizures in freely-moving rats. Neurosci. Bull. 2015, 31, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Sosicka, P.; Williams, D.J.; Bowyer, M.E.; Ressler, A.K.; Kohrt, S.E.; Muron, S.J.; Crino, P.B.; Freeze, H.H.; Boland, M.J.; et al. SLC35A2 loss-of-function variants affect glycomic signatures, neuronal fate and network dynamics. Brain 2025, 148, 4259–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.C. The Role of Homeostatic Plasticity in Post-Traumatic Epilepsy; Indiana University Indianapolis: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shah, R.; Budhhraja, R.; Radenkovic, S.; Preston, G.; King, A.T.; Sabry, S.; Bleukx, C.; Shammas, I.; Young, L.; Chandran, J.; et al. Network Hypoactivity in ALG13-CDG: Disrupted Developmental Pathways and E/I Imbalance as Early Drivers of Neurological Features in CDG. Cells 2026, 15, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020147

Shah R, Budhhraja R, Radenkovic S, Preston G, King AT, Sabry S, Bleukx C, Shammas I, Young L, Chandran J, et al. Network Hypoactivity in ALG13-CDG: Disrupted Developmental Pathways and E/I Imbalance as Early Drivers of Neurological Features in CDG. Cells. 2026; 15(2):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020147

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Rameen, Rohit Budhhraja, Silvia Radenkovic, Graeme Preston, Alexia Tyler King, Sahar Sabry, Charlotte Bleukx, Ibrahim Shammas, Lyndsay Young, Jisha Chandran, and et al. 2026. "Network Hypoactivity in ALG13-CDG: Disrupted Developmental Pathways and E/I Imbalance as Early Drivers of Neurological Features in CDG" Cells 15, no. 2: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020147

APA StyleShah, R., Budhhraja, R., Radenkovic, S., Preston, G., King, A. T., Sabry, S., Bleukx, C., Shammas, I., Young, L., Chandran, J., Byeon, S. K., Hrstka, R., Smith, D. Y., IV, Staff, N. P., Drake, R., Sloan, S. A., Pandey, A., Morava, E., & Kozicz, T. (2026). Network Hypoactivity in ALG13-CDG: Disrupted Developmental Pathways and E/I Imbalance as Early Drivers of Neurological Features in CDG. Cells, 15(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020147