Impact of Menopause and Associated Hormonal Changes on Spine Health in Older Females: A Review

Highlights

- Menopausal hormone fluctuations are associated with intervertebral disc degeneration, facet joint osteoarthritis, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, sarcopenia, sympathetic innervation alterations, and systemic inflammation; however, specific mechanisms remain poorly understood.

- Evidence suggests exercise and parathyroid hormone are promising therapeutic options for menopausal low back pain (LBP), while hormone replacement therapy and bisphosphonates seem less promising.

- This review highlights critical windows for research to uncover mechanisms and inform improved, targeted treatments for menopause related LBP.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

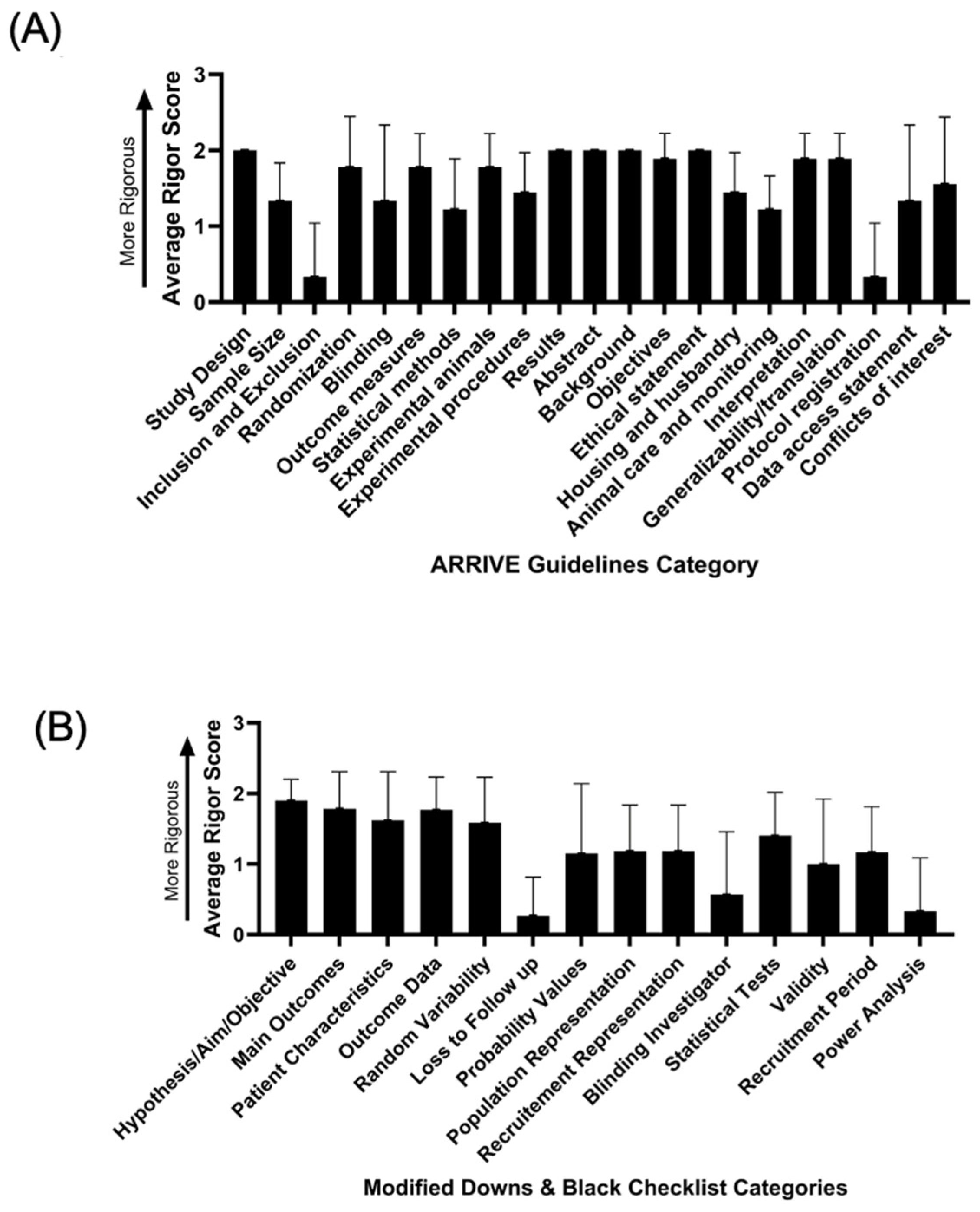

3.1. Article Inclusion and Rigour and Reproducibility Analysis

3.2. Low Back Pain Pathophysiology

3.2.1. Contributions to LBP from Spinal Tissues

Intervertebral Disc

Vertebral Endplate

Spinal Muscles

Facet Joint

Ligamentum Flavum

3.2.2. Neurologic Contributions to LBP

3.2.3. Contributions to LBP from Systemic Tissues

3.2.4. Sociopsychological Contributions to LBP

3.3. Treatments for Post-Menopausal Low Back Pain

3.3.1. Hormone Replacement Therapy

3.3.2. Exercise

3.3.3. Other Non-HRT Treatments

4. Discussion

Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LBP | Low Back Pain |

| IDD | Intervertebral Disc Degeneration |

| US | United States |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ODI | Oswestry Disability Index |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| HRT | Hormonal Replacement Therapy |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| LSS | Lumbar Spinal Stenosis |

| ALP | Bone Formation Marker |

| u-NTx | Bone Resorption Marker |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 |

| CRP | C-reactive Protein |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating Hormone |

| VCD | 4-Vinylcyclohexene Diepoxide |

References

- Vrbanic, T.S. Low Back Pain—From Definition to Diagnosis. Reumatizam 2011, 58, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, N.; Emanski, E.; Knaub, M.A. Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 98, 777–789, xii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Low Back Pain, 1990–2020, Its Attributable Risk Factors, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Lui, A.; Matsoyan, A.; Safaee, M.M.; Aryan, H.; Ames, C. Comparative Review of the Socioeconomic Burden of Lower Back Pain in the United States and Globally. Neurospine 2024, 21, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfirrmann, C.W.; Metzdorf, A.; Zanetti, M.; Hodler, J.; Boos, N. Magnetic Resonance Classification of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Spine 2001, 26, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952; discussion 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Patiman; Liu, B.; Zhang, R.; Ma, X.; Guo, H. Correlation between Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Bone Mineral Density Difference: A Retrospective Study of Postmenopausal Women Using an Eight-Level MRI-Based Disc Degeneration Grading System. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, G.E.; Fritz, J.M.; Delitto, A.; McGill, S.M. Preliminary Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Determining Which Patients with Low Back Pain Will Respond to a Stabilization Exercise Program. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.C.; Brant-Zawadzki, M.N.; Obuchowski, N.; Modic, M.T.; Malkasian, D.; Ross, J.S. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Lumbar Spine in People without Back Pain. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, S.; Huang, W.; Conley, Y.; Vo, N.; Schneider, M.; Sowa, G. Pain-Related Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms: Association with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Patient Experience and Non-Surgical Treatment Outcomes. Eur. Spine J. 2024, 33, 2213–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, S.; Huang, W.; Perera, S.; Conley, Y.; Belfer, I.; Jayabalan, P.; Tremont, K.; Coelho, P.; Ernst, S.; Cortazzo, M.; et al. Association of Protein and Genetic Biomarkers with Response to Lumbar Epidural Steroid Injections in Subjects with Axial Low Back Pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; Roberts, S. Degeneration of the Intervertebral Disc. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2003, 5, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.J. Menopause as a Potential Cause for Higher Prevalence of Low Back Pain in Women Than in Age-Matched Men. J. Orthop. Translat. 2016, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wáng, Y.X.J.; Wáng, J.-Q.; Káplár, Z. Increased Low Back Pain Prevalence in Females Than in Males after Menopause Age: Evidences Based on Synthetic Literature Review. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2016, 6, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.X.; Griffith, J.F. Effect of Menopause on Lumbar Disk Degeneration: Potential Etiology. Radiology 2010, 257, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.S. Disc Degeneration. Its Frequency and Relationship to Symptoms. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1969, 28, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcouffe, J.; Manillier, P.; Brehier, M.; Fabin, C.; Faupin, F. Analysis by Sex of Low Back Pain among Workers from Small Companies in the Paris Area: Severity and Occupational Consequences. Occup. Environ. Med. 1999, 56, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.Y.; Song, X.X.; Li, X.F. The Role of Estrogen in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Steroids 2020, 154, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A. Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Women: Still More Questions to Be Answered. Menopause 2009, 16, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoseph, E.T.; Taiwo, R.; Kiapour, A.; Touponse, G.; Massaad, E.; Theologitis, M.; Wu, J.Y.; Williamson, T.; Zygourakis, C.C. Pregnancy-Related Spinal Biomechanics: A Review of Low Back Pain and Degenerative Spine Disease. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society” Advisory Panel. The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022, 29, 767–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poomalar, G.K.; Arounassalame, B. The Quality of Life during and after Menopause among Rural Women. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinoga, M.; Majchrzycki, M.; Piotrowska, S. Low Back Pain in Women before and after Menopause. Przegląd Menopauzalny 2015, 14, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoeke, C.E.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Guthrie, J.R.; Dennerstein, L. The Relationship of Reports of Aches and Joint Pains to the Menopausal Transition: A Longitudinal Study. Climacteric 2008, 11, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.; Chen, H.; Mei, L.; Yu, W.; Zhu, K.; Liu, F.; Chen, Z.; Xiang, G.; Chen, M.; Weng, Q.; et al. Association between Menopause and Lumbar Disc Degeneration: An Mri Study of 1,566 Women and 1,382 Men. Menopause 2017, 24, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, H. The Demography of Menopause. Maturitas 1996, 23, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichchou, L.; Allali, F.; Rostom, S.; Bennani, L.; Hmamouchi, I.; Abourazzak, F.Z.; Khazzani, H.; El Mansouri, L.; Abouqal, R.; Hajjaj-Hassouni, N. Relationship between Spine Osteoarthritis, Bone Mineral Density and Bone Turn over Markers in Post Menopausal Women. BMC Womens Health 2010, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charde, S.H.; Joshi, A.; Raut, J. A Comprehensive Review on Postmenopausal Osteoporosis in Women. Cureus 2023, 15, e48582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, C. Association of Hormone Preparations with Bone Mineral Density, Osteopenia, and Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2018. Menopause 2023, 30, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The Arrive Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, A.D.; Melrose, J. Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and How It Leads to Low Back Pain. JOR Spine 2023, 6, e1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Forell, G.A.; Stephens, T.K.; Samartzis, D.; Bowden, A.E. Low Back Pain: A Biomechanical Rationale Based on “Patterns” of Disc Degeneration. Spine 2015, 40, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Han, B.; Song, C.; Yan, L. Molecular Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies for Discogenic Lumbar Pain. Immunol. Res. 2025, 73, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Isa, I.L.; Teoh, S.L.; Mohd Nor, N.H.; Mokhtar, S.A. Discogenic Low Back Pain: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatments of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wáng, Y.X. Continued Progression of Lumbar Disc Degeneration in Postmenopausal Women. Climacteric 2015, 18, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscat Baron, Y. Menopause and the Intervertebral Disc. Menopause 2017, 24, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Chen, H.L.; Feng, X.Z.; Xiang, G.H.; Zhu, S.P.; Tian, N.F.; Jin, Y.L.; Fang, M.Q.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.Z. Menopause Is Associated with Lumbar Disc Degeneration: A Review of 4230 Intervertebral Discs. Climacteric 2014, 17, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.J. Postmenopausal Chinese Women Show Accelerated Lumbar Disc Degeneration Compared with Chinese Men. J. Orthop. Translat. 2015, 3, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.X.; Shi, S.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.F.; Yu, B.W. Estrogen Receptors Involvement in Intervertebral Discogenic Pain of the Elderly Women: Colocalization and Correlation with the Expression of Substance P in Nucleus Pulposus. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38136–38144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.X.; Jin, L.Y.; Li, X.F.; Luo, Y.; Yu, B.W. Substance P Mediates Estrogen Modulation Proinflammatory Cytokines Release in Intervertebral Disc. Inflammation 2021, 44, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotz, J.C.; Fields, A.J.; Liebenberg, E.C. The Role of the Vertebral End Plate in Low Back Pain. Glob. Spine J. 2013, 3, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinsky, B.G.; Bonnevie, E.D.; Mandalapu, S.A.; Pickup, S.; Wang, C.; Han, L.; Mauck, R.L.; Smith, H.E.; Gullbrand, S.E. Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Is Associated with Aberrant Endplate Remodeling and Reduced Small Molecule Transport. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Yuxiao, L.; Huilan, L.; Jun, H.; Dong, L. Correlation Analysis of Osteoporosis and Vertebral Endplate Defects Using Ct and Mri Imaging: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1649477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, J.F.; Sparrey, C.J.; Been, E.; Kramer, P.A. Morphological and Postural Sexual Dimorphism of the Lumbar Spine Facilitates Greater Lordosis in Females. J. Anat. 2016, 229, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalla, S.; Lebib, S.B.; Miri, I.; Koubaa, S.; Rahali, H.; Salah, F.Z.; Dziri, C. Study of the Postural Profile and Spinal Static for Menopausal-Women with Chronic Low Back Pain. Ann. Readapt. Med. Phys. 2008, 51, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsanz, V.; Boechat, M.I.; Gilsanz, R.; Loro, M.L.; Roe, T.F.; Goodman, W.G. Gender Differences in Vertebral Sizes in Adults: Biomechanical Implications. Radiology 1994, 190, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponrartana, S.; Aggabao, P.C.; Dharmavaram, N.L.; Fisher, C.L.; Friedlich, P.; Devaskar, S.U.; Gilsanz, V. Sexual Dimorphism in Newborn Vertebrae and Its Potential Implications. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsanz, V.; Wren, T.A.L.; Ponrartana, S.; Mora, S.; Rosen, C.J. Sexual Dimorphism and the Origins of Human Spinal Health. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalli, I.; Niglas, M.; Naeini, M.K.; Freidin, M.; Thomas, L.; Menni, C.; Williams, F. Paraspinal Muscle Quality in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Muscle Atrophy and Fat Infiltration. Eur. Spine J. 2025. OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, M.; Aoyama, T.; Murakami, T.; Yanase, K.; Ji, X.; Tateuchi, H.; Ichihashi, N. Association of Low Back Pain with Muscle Stiffness and Muscle Mass of the Lumbar Back Muscles, and Sagittal Spinal Alignment in Young and Middle-Aged Medical Workers. Clin. Biomech. 2017, 49, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, A.M.; Brown, S.H.M. Paraspinal Muscle Pathophysiology Associated with Low Back Pain and Spine Degenerative Disorders. JOR Spine 2021, 4, e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltais, M.L.; Desroches, J.; Dionne, I.J. Changes in Muscle Mass and Strength after Menopause. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 2009, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.C.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Lowe, D.A. Aging of the Musculoskeletal System: How the Loss of Estrogen Impacts Muscle Strength. Bone 2019, 123, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodete, C.S.; Thuraka, B.; Pasupuleti, V.; Malisetty, S. Hormonal Influences on Skeletal Muscle Function in Women across Life Stages: A Systematic Review. Muscles 2024, 3, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; King, A.I. Mechanism of Facet Load Transmission as a Hypothesis for Low-Back Pain. Spine 1984, 9, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosabbir, A. Mechanisms Behind the Development of Chronic Low Back Pain and Its Neurodegenerative Features. Life 2023, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, L.; Hunter, D.J. Lumbar Facet Joint Osteoarthritis: A Review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 37, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, K.; Chen, K.; Yang, H. Estrogen Deficiency Accelerates Lumbar Facet Joints Arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinkaya, N.; Yildirim, T.; Demir, S.; Alkan, O.; Sarica, F.B. Factors Associated with the Thickness of the Ligamentum Flavum: Is Ligamentum Flavum Thickening Due to Hypertrophy or Buckling? Spine 2011, 36, E1093–E1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairyo, K.; Biyani, A.; Goel, V.; Leaman, D.; Booth, R., Jr.; Thomas, J.; Gehling, D.; Vishnubhotla, L.; Long, R.; Ebraheim, N. Pathomechanism of Ligamentum Flavum Hypertrophy: A Multidisciplinary Investigation Based on Clinical, Biomechanical, Histologic, and Biologic Assessments. Spine 2005, 30, 2649–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, H.; Sairyo, K.; Biyani, A.; Leaman, D.; Yeasting, R.; Higashino, K.; Sakai, T.; Katoh, S.; Sano, T.; Goel, V.K.; et al. Pathomechanism of Loss of Elasticity and Hypertrophy of Lumbar Ligamentum Flavum in Elderly Patients with Lumbar Spinal Canal Stenosis. Spine 2007, 32, 2805–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwal, P.; Nguyen-Thai, A.M.; Alexander, P.G.; Sowa, G.A.; Vo, N.V.; Lee, J.Y. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Hypertrophy of Ligamentum Flavum. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Hu, C.-K.; Chen, P.-R.; Chen, Y.-S.; Sun, J.-S.; Chen, M.-H. Dose-Dependent Regulation of Cell Proliferation and Collagen Degradation by Estradiol on Ligamentum Flavum. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2014, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westhoff, C.C.; Peterlein, C.D.; Daniel, H.; Paletta, J.R.; Moll, R.; Ramaswamy, A.; Lakemeier, S. Expression of Estrogen Receptor Alpha and Evaluation of Histological Degeneration Scores in Fibroblasts of Hypertrophied Ligamentum Flavum: A Qualitative Study. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J.M.; Ozaktay, A.C.; Yamashita, T.; Avramov, A.; Getchell, T.V.; King, A.I. Mechanisms of Low Back Pain: A Neurophysiologic and Neuroanatomic Study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1997, 335, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, Y.; Connolly, M.; Srinivasan, A.; Kim, J.; Capizzano, A.A.; Moritani, T. Mechanisms and Origins of Spinal Pain: From Molecules to Anatomy, with Diagnostic Clues and Imaging Findings. Radiographics 2020, 40, 1163–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Meng, F.; Huang, W.; Cui, Y.; Meng, F.; Wu, S.; Xu, H. The Alterations in the Brain Corresponding to Low Back Pain: Recent Insights and Advances. Neural Plast. 2024, 2024, 5599046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.Q. Estrogen Facilitates Spinal Cord Synaptic Transmission Via Membrane-Bound Estrogen Receptors: Implications for Pain Hypersensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 33268–33281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amandusson, A.; Blomqvist, A. Estrogenic Influences in Pain Processing. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 34, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Gu, Y.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Estrogen Affects Neuropathic Pain through Upregulating N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Acid Receptor 1 Expression in the Dorsal Root Ganglion of Rats. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mai, C.L.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, Z.J.; Jie, Y.T.; Mai, J.Z.; Liu, C.; Xie, M.X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.G. The Causal Role of Magnesium Deficiency in the Neuroinflammation, Pain Hypersensitivity and Memory/Emotional Deficits in Ovariectomized and Aged Female Mice. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 6633–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Jiao, C.; Wang, L.; Fu, F.; Feng, Y.; Qian, X.; et al. Estrogen modulation of pain perception with a novel 17β-estradiol pretreatment regime in ovariectomized rats. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.T.; Alipui, D.O.; Sison, C.P.; Bloom, O.; Quraishi, S.; Overby, M.C.; Levine, M.; Chahine, N.O. Serum Levels of the Proinflammatory Cytokine Interleukin-6 Vary Based on Diagnoses in Individuals with Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuertz, K.; Haglund, L. Inflammatory Mediators in Intervertebral Disk Degeneration and Discogenic Pain. Glob. Spine J. 2013, 3, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtori, S.; Miyagi, M.; Inoue, G. Sensory Nerve Ingrowth, Cytokines, and Instability of Discogenic Low Back Pain: A Review. Spine Surg. Relat. Res. 2018, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Muñoz, V.; Suárez-Gómez, S.; Acevedo-González, J.C. Intestinal-Intervertebral Disc Axis: Relationship between Dysbiosis and Lower Back Pain Due to Intervertebral Disc Degeneration (P4-7.007). Neurology 2025, 104, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Kakiuchi, T.; Esaki, M.; Tsukamoto, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Hirata, H.; Yabuki, S.; Mawatari, M. Gut-Spine Axis: A Possible Correlation between Gut Microbiota and Spinal Degenerative Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1290858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyasa, I.K.; Lestari, A.A.W.; Setiawan, I.G.N.Y.; Mahadewa, T.G.B.; Widyadharma, I.P.E. Elevated High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Interleukin-6 Plasma as Risk Factors for Symptomatic Lumbar Osteoarthritis in Postmenopausal Women. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2107–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enrico, V.T.; Anderst, W.; Bell, K.M.; Coelho, J.P.; Darwin, J.; Delitto, A.; Greco, C.M.; Lee, J.Y.; McKernan, G.P.; Patterson, C.G.; et al. Plasma Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in an Observational Chronic Low Back Pain Cohort. JOR Spine 2025, 8, e70095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Chen, S.; Klyne, D.M.; Harrich, D.; Ding, W.; Yang, S.; Han, F.Y. Low Back Pain and Osteoarthritis Pain: A Perspective of Estrogen. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseĭkin, I.A.; Goĭdenko, V.S.; Aleksandrov, V.I.; Rudenko, I.V.; Borzunova, T.A.; Barashkov, G.N. Gender Features of Low Back Pain Syndromes. Zhurnal Nevrol. I Psikhiatrii Im. SS Korsakova 2010, 110, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.A.; Lin, J.; Qi, Q.; Usyk, M.; Isasi, C.R.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Derby, C.A.; Santoro, N.; Perreira, K.M.; Daviglus, M.L.; et al. Menopause Is Associated with an Altered Gut Microbiome and Estrobolome, with Implications for Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. mSystems 2022, 7, e0027322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kverka, M.; Stepan, J.J. Associations among Estrogens, the Gut Microbiome and Osteoporosis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2024, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijnhoven, H.A.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Smit, H.A.; Picavet, H.S.J. Hormonal and Reproductive Factors Are Associated with Chronic Low Back Pain and Chronic Upper Extremity Pain in Women—The Morgen Study. Spine 2006, 31, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Zhou, J.; Lin, C.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Rao, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; et al. A Causal Examination of the Correlation between Hormonal and Reproductive Factors and Low Back Pain. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1326761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuch, I.; Heuch, I.; Hagen, K.; Storheim, K.; Zwart, J.A. Does the Risk of Chronic Low Back Pain Depend on Age at Menarche or Menopause? A Population-Based Cross-Sectional and Cohort Study: The Trøndelag Health Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmons, D.P.; van Hemert, A.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Valkenburg, H.A. A Longitudinal Study of Back Pain and Radiological Changes in the Lumbar Spines of Middle Aged Women. I. Clinical Findings. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1991, 50, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braden, J.B.; Young, A.; Sullivan, M.D.; Walitt, B.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Martin, L. Predictors of Change in Pain and Physical Functioning among Post-Menopausal Women with Recurrent Pain Conditions in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Cohort. J. Pain 2012, 13, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavudu, M.V.; Divya, J.N.; Ranganathan, P.; Mahesh Kumar, P.G.; Hari Hara Subramanyan, P.V.; Subramanian, S. Determining the Predominant Risk Factor of Low Back Pain among Pre-Menopausal and Post-Menopausal Women. Int. J. Exp. Res. Rev. 2023, 34, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczkiewicz, D.; Owoc, A.; Sarecka-Hujar, B.; Saran, T.; Bojar, I. Impact of Spinal Pain on Daily Living Activities in Postmenopausal Women Working in Agriculture. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017, 24, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, L. Hysterectomy-a Possible Risk Factor for Operative Intervention in Female Patients for Degenerative Lumbar Spine Conditions: A Case Control and Cohort Study. Spine J. 2024, 24, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.S.; Woods, N.F. Pain Symptoms during the Menopausal Transition and Early Postmenopause. Climacteric 2010, 13, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiri, R.; Karppinen, J.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Solovieva, S.; Viikari-Juntura, E. The Association between Obesity and Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, I.R.; Morelhao, P.K.; Verhagen, A.; Gobbi, C.; Oliveira, C.B.; Silva, N.S.; Lustosa, L.P.; Franco, M.R.; Pinto, R.Z. Does the Number of Comorbidities Predict Pain and Disability in Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain? A Longitudinal Study with 6- and 12-Month Follow-Ups. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2024, 47, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, M.; Cote, P.; French, M.R.; Hawker, G.A. The Association between Low Back Pain and Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2010, 33, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.J.; Licciardone, J.C. The Effect of Long-Term Opioid Use on Back-Specific Disability and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Osteopath Med. 2022, 122, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynhildsen, J.O.; Björs, E.; Skarsgård, C.; Hammar, M.L. Is Hormone Replacement Therapy a Risk Factor for Low Back Pain among Postmenopausal Women? Spine 1998, 23, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.L.; Orsini, M.R.; Saraifoger, S.; Ortolani, S.; Radaelli, G.; Betti, S. Quality of Life in Post-Menopausal Osteoporosis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2005, 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duymaz, T.; Yagci, N.; Gayef, A.; Telatar, B. Study on the Relationship between Low Back Pain and Emotional State, Sleep and Quality of Life in Postmenopausal Women. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2020, 33, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, S.; Behnezhad, S.; Azad, E. Back Pain and Depressive Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2020, 91217420913001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.S.; Mendonça, L.V.F.; Sampaio, R.S.M.; de Castro-Lopes, J.M.P.D.; de Azevedo, L.F.R. The Impact of Anxiety and Depression on the Outcomes of Chronic Low Back Pain Multidisciplinary Pain Management-a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study in Pain Clinics with One-Year Follow-Up. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qi, L.; Zhang, H.; Yu, D.; Shi, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, T. Smoking and BMI Mediate the Causal Effect of Education on Lower Back Pain: Observational and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1288170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, G.; Tobias, J.H.; Paskins, Z.; Khera, T.K.; Huggins, C.J.; Allison, S.J.; Abasolo, D.; Clark, E.M.; Ireland, A. Daily Pain Severity but Not Vertebral Fractures Is Associated with Lower Physical Activity in Postmenopausal Women with Back Pain. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2024, 32, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherad, M.; Rosengren, B.E.; Hasserius, R.; Nilsson, J.; Redlund-Johnell, I.; Ohlsson, C.; Mellström, D.; Lorentzon, M.; Ljunggren, Ö.; Karlsson, M.K. Risk Factors for Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Elderly Men—The MrOS Sweden Study. Age Ageing 2016, 46, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, A.; Djordjevic, G.; Ljubisavljevic, S.; Zivadinovic, B.; Stojanov, J. Quality of Life, and Quality of Sleep in the Working Population with Chronic Low Back Pain: A 2-Year Follow-Up. Medicine 2025, 104, e45321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urquhart, D.M.; Bell, R.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Cui, J.; Forbes, A.; Davis, S.R. Low Back Pain and Disability in Community-Based Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Menopause 2009, 16, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, H.O.; Andersson, G.B.; Hagstad, A.; Jansson, P.O. The Relationship of Low-Back Pain to Pregnancy and Gynecologic Factors. Spine 1990, 15, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Song, R. Bone Mineral Density and Perceived Menopausal Symptoms: Factors Influencing Low Back Pain in Postmenopausal Women. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhang, J. Smoking, Alcohol and Coffee Consumption and Risk of Low Back Pain: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaudo, C.M.; Van de Velde, M.; Steyaert, A.; Mouraux, A. Navigating the Biopsychosocial Landscape: A Systematic Review on the Association between Social Support and Chronic Pain. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0321750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbjörnsson, C.O.; Alfredsson, L.; Fredriksson, K.; Köster, M.; Michélsen, H.; Vingård, E.; Torgén, M.; Kilbom, A. Psychosocial and Physical Risk Factors Associated with Low Back Pain: A 24 Year Follow up among Women and Men in a Broad Range of Occupations. Occup. Environ. Med. 1998, 55, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, D.R.; Chatterjee, A.; McCroskey, A.L.; Ahmadi, T.; Simmelink, D.; Oldfield, E.C., IV; Pryor, C.R.; Faschan, M.; Raulli, O. A Review of Select Centralized Pain Syndromes:Relationship with Childhood Sexual Abuse, Opiate Prescribing, and Treatment Implications for the Primary Care Physician. Health Serv. Res. Manag. Epidemiol. 2015, 2, 2333392814567920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Haldeman, S.; Lu, M.-L.; Baker, D. Low Back Pain Prevalence and Related Workplace Psychosocial Risk Factors: A Study Using Data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2016, 39, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, D.S.; Vogt, M.T.; Nevitt, M.C.; Cauley, J.A. Back Problems among Postmenopausal Women Taking Estrogen Replacement Therapy: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Spine 2001, 26, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuch, I.; Heuch, I.; Hagen, K.; Storheim, K.; Zwart, J.A. Menopausal Hormone Therapy, Oral Contraceptives and Risk of Chronic Low Back Pain: The Hunt Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Hong, J.Y.; Han, K.; Han, S.W.; Chun, E.M. Relationship between Hormone Replacement Therapy and Spinal Osteoarthritis: A Nationwide Health Survey Analysis of the Elderly Korean Population. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyllönen, E.S.; Heikkinen, J.E.; Väänänen, H.K.; Kurttila-Matero, E.; Wilen-Rosenqvist, G.; Lankinen, K.S.; Vanharanta, J.H. Influence of Estrogen-Progestin Replacement Therapy and Exercise on Lumbar Spine Mobility and Low Back Symptoms in a Healthy Early Postmenopausal Female Population: A 2-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Spine J. 1998, 7, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyllönen, E.S.; Väänänen, H.K.; Vanharanta, J.H.; Heikkinen, J.E. Influence of Estrogen-Progestin Treatment on Back Pain and Disability among Slim Premenopausal Women with Low Lumbar Spine Bone Mineral Density. A 2-Year Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trial. Spine 1999, 24, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty-Poumarat, C.; Ostertag, A.; Baudoin, C.; Marpeau, M.; de Vernejoul, M.C.; Cohen-Solal, M. Does Hormone Replacement Therapy Prevent Lateral Rotatory Spondylolisthesis in Postmenopausal Women? Eur. Spine J. 2012, 21, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Huo, Y.; Tian, T.; Yang, D.; Ma, L.; Yang, S.; Ding, W. 17β-Estradiol Alleviates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration by Inhibiting Nf-Κb Signal Pathway. Life Sci. 2021, 284, 119874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.Y.; Lv, Z.D.; Wang, K.; Qian, L.; Song, X.X.; Li, X.F.; Shen, H.X. Estradiol Alleviates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration through Modulating the Antioxidant Enzymes and Inhibiting Autophagy in the Model of Menopause Rats. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7890291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, S.; Yang, Z.; Hong, H.; Zou, D.; Song, C.; Li, W.; Leng, H. Htra1 from Ovx Rat Osteoclasts Causes Detrimental Effects on Endplate Chondrocytes through Nf-Κb. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Bendinelli, B.; Assedi, M.; Occhini, D.; Castaldo, M.; Fabiano, J.; Petranelli, M.; Migliolo, M.; Monaci, M.; Masala, G. Low Back Pain in Healthy Postmenopausal Women and the Effect of Physical Activity: A Secondary Analysis in a Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisinger, E.; Alacamlioglu, Y.; Pils, K.; Bosina, E.; Metka, M.; Schneider, B.; Ernst, E. Exercise Therapy for Osteoporosis: Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 1996, 30, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.B.; Lima, V.P.; Mello, D.B.; Lopes, G.C.; Peixoto, J.C.; Santos, A.O.D.; Nunes, R.A.; Souza Vale, R.G. Effects of Pilates with and without Elastic Resistance on Health Variables in Postmenopausal Women with Low Back Pain. Pain Manag. 2022, 12, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Caguicla, J.M.; Park, S.; Kwak, D.J.; Won, D.Y.; Park, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, M. Effects of 8-Week Pilates Exercise Program on Menopausal Symptoms and Lumbar Strength and Flexibility in Postmenopausal Women. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2016, 12, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageswari, C.; Meena, N. Effects of Pilates Exercises Versus Conventional Exercises among Post-Menopausal Women Suffering from Non-Specific Low Back Pain, by Improving Lumbar Flexibility, Endurance, and Quality of Life—A Comparative Study. Int. J. Physiother. 2025, 12, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Yaqoob, I.; Shakil-Ur-Rehman, S.; Ghous, M.; Ghazal, J.; Namroz, N. Effects of Core Muscle Stability on Low Back Pain and Quality of Life in Post- Menopausal Women: A Comparative Study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.S.; Santos, P.d.J.; Vasconcelos, A.B.S.; Gomes, A.C.A.; de Oliveira, L.M.; Souza, P.R.M.; Heredia-Elvar, J.R.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E. Neuroendocrine Effects of a Single Bout of Functional and Core Stabilization Training in Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Crossover Study. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cergel, Y.; Topuz, O.; Alkan, H.; Sarsan, A.; Akkoyunlu, N.S. The Effects of Short-Term Back Extensor Strength Training in Postmenopausal Osteoporotic Women with Vertebral Fractures: Comparison of Supervised and Home Exercise Program. Arch. Osteoporos. 2019, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadouria, N.; Holguin, N. Osteoporosis Treatments for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Back Pain: A Perspective. JBMR Plus 2024, 8, ziae048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.D.; Chines, A.A.; Christiansen, C.; Hoeck, H.C.; Kendler, D.L.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Woodson, G.; Levine, A.B.; Constantine, G.; Delmas, P.D. Effects of Bazedoxifene on Bmd and Bone Turnover in Postmenopausal Women: 2-Yr Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-, and Active-Controlled Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, J.; Takeda, T.; Ichimura, S.; Matsu, K.; Uzawa, M. Effects of Cyclical Etidronate with Alfacalcidol on Lumbar Bone Mineral Density, Bone Resorption, and Back Pain in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Sci. 2003, 8, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, B. Relationship between Bone Mineral Density and the Frequent Administration of Epidural Steroid Injections in Postmenopausal Women with Low Back Pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2014, 19, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Griffith, J.F. Menopause Causes Vertebral Endplate Degeneration and Decrease in Nutrient Diffusion to the Intervertebral Discs. Med. Hypotheses 2011, 77, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmer, G.; Hettinger, Z.R.; Tuakli-Wosornu, Y.; Skidmore, E.; Silver, J.K.; Thurston, R.C.; Lowe, D.A.; Ambrosio, F. Female Aging: When Translational Models Don’t Translate. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhu, R.; Sheng, Z.; Qin, G.; Luo, X.; Qin, Q.; Song, C.; Li, L.; Jin, P.; Yang, G.; et al. Multiple Doses of Shr-1222, a Sclerostin Monoclonal Antibody, in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalation Phase 1 Trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1168757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, D.; Tian, F. Parathyroid Hormone (1–34) Retards the Lumbar Facet Joint Degeneration and Activates Wnt/Β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Ovariectomized Rats. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Wei, Y.; Cai, C.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; Gong, M.; et al. Moderate Static Magnetic Fields Prevent Estrogen Deficiency-Induced Bone Loss: Evidence from Ovariectomized Mouse Model and Small Sample Size Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.L.; Pollow, D.P.; Hoyer, P.B. The VCD Mouse Model of Menopause and Perimenopause for the Study of Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease and the Metabolic Syndrome. Physiology 2016, 31, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmer, G.; Iijima, H.; Hettinger, Z.R.; Jackson, N.; Bergmann, J.; Bean, A.C.; Shahshahan, N.; Creed, E.; Kopchak, R.; Wang, K.; et al. Menopause-induced 17β-estradiol and progesterone loss increases senescence markers, matrix disassembly and degeneration in mouse cartilage. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| General LBP Risk Factors | Female Non-Hormonal Risk Factors | Female Potentially Hormone Mediated Risk Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Structural Changes | IDD [32,33,34,35] | IDD [39] | IDD [18,25,36,37,38,40,41] |

| Vertebral endplate degeneration [44] | Vertebral endplate degeneration [45,46,47,48,49] | Facet joint OA [13,59] | |

| Spinal Muscles [50,51,52] | Ligamentum flavum hypertrophy [64,65] | ||

| Facet joint OA [56,57,58] | Sympathetic Innervation [69,70,71,72] | ||

| Ligamentum flavum hypertrophy [60,61,62,63] | |||

| Sympathetic innervation [66,67,68] | |||

| Systemic inflammation [74,75,76,80] | |||

| Systemic Changes | Dysregulated gut microbiome [77,78] | Sarcopenia [53,54,55] | |

| Pain in the knees and hips [88,95] | Gut microbiome [83,84] | ||

| High BMI [24,89,90,91,94] | |||

| Comorbidities [89,96] | |||

| Gynecological Conditions | Severe associated menopausal symptoms [93] | ||

| Hysterectomy [85,92] | |||

| Previously irregular menstruation [85] | |||

| Early menarche [86,87] | |||

| Young maternal age at first childbirth [19,85,86] | |||

| Oral contraceptive use [85] | |||

| Sociopsychological Conditions | Chronic opioid use [89,97] | High perceived stress [90] | |

| Anxiety [90,100,102] | Unemployment [24,107] | ||

| Lower education level [91,103] | Headaches [88] | ||

| Impaired physical activity [89,99,104,105] | History of sexual abuse [93] | ||

| Poor sleep quality [100,106] | Poor interpersonal relationships [107] | ||

| Having disability accommodations [107] | |||

| Consuming alcohol [107] | |||

| Working relatively longer hours [90] | |||

| Drinking coffee [109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chagas, J.; Gilmer, G.; Sowa, G.; Vo, N. Impact of Menopause and Associated Hormonal Changes on Spine Health in Older Females: A Review. Cells 2026, 15, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020148

Chagas J, Gilmer G, Sowa G, Vo N. Impact of Menopause and Associated Hormonal Changes on Spine Health in Older Females: A Review. Cells. 2026; 15(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020148

Chicago/Turabian StyleChagas, Julia, Gabrielle Gilmer, Gwendolyn Sowa, and Nam Vo. 2026. "Impact of Menopause and Associated Hormonal Changes on Spine Health in Older Females: A Review" Cells 15, no. 2: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020148

APA StyleChagas, J., Gilmer, G., Sowa, G., & Vo, N. (2026). Impact of Menopause and Associated Hormonal Changes on Spine Health in Older Females: A Review. Cells, 15(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020148