Gene Editing Therapies Targeting Lipid Metabolism for Cardiovascular Disease: Tools, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Progress

Highlights

- Gene editing therapies targeting liver-specific genes that are involved in lipid metabolism for treating cardiovascular diseases (LivGETx-CVD) have progressed from conceptual frameworks to early-phase clinical trials, with the potential to redefine prevention and long-term management of dyslipidemia and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.

- Human genetics and preclinical studies suggest several promising genes, such as PCSK9, ANGPTL3, IDOL, ASGR1, APOC3, and LPA, for targeting in LivGETx-CVD to achieve durable LDL-C and triglyceride lowering after a single administration.

- LivGETx-CVD is a potential “vaccine-like” intervention for cardiovascular disease, offering long-term protection without the adherence challenges and access barriers of chronic lipid-lowering medications.

- To translate LivGETx-CVD beyond rare, severe dyslipidemias toward broader preventive use, the field must address outstanding challenges in delivery safety, off-target effects, cost-effectiveness, as well as ethical and regulatory oversight, requiring larger and longer clinical trials and societal-level discussion.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Gene Editing Tools

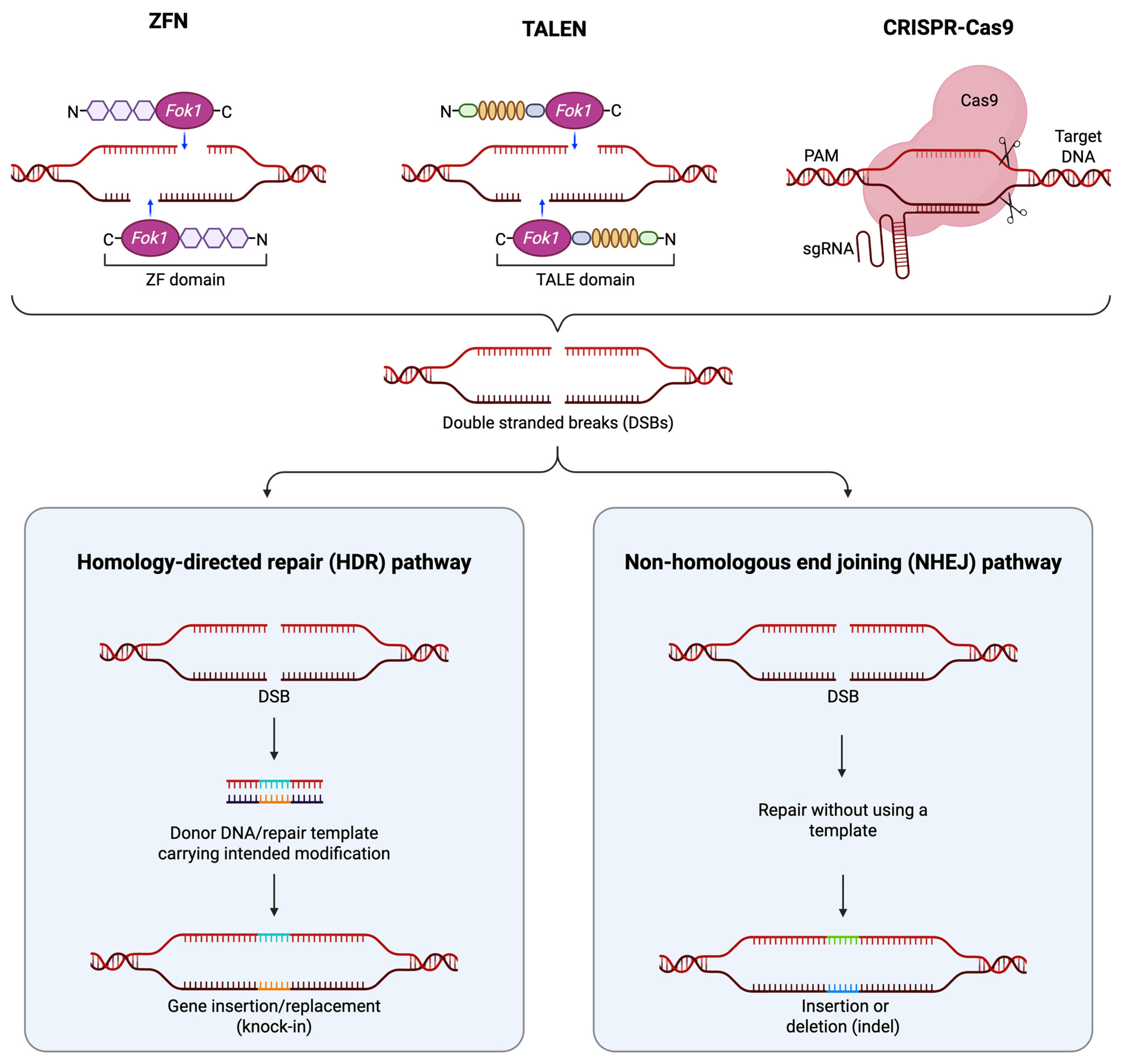

2.1. Zinc-Finger Nucleases

2.2. Transcription Activator-like Effector Nucleases

2.3. CRISPR/Cas9

2.4. Nuclease-Inactive Cas9 Variants

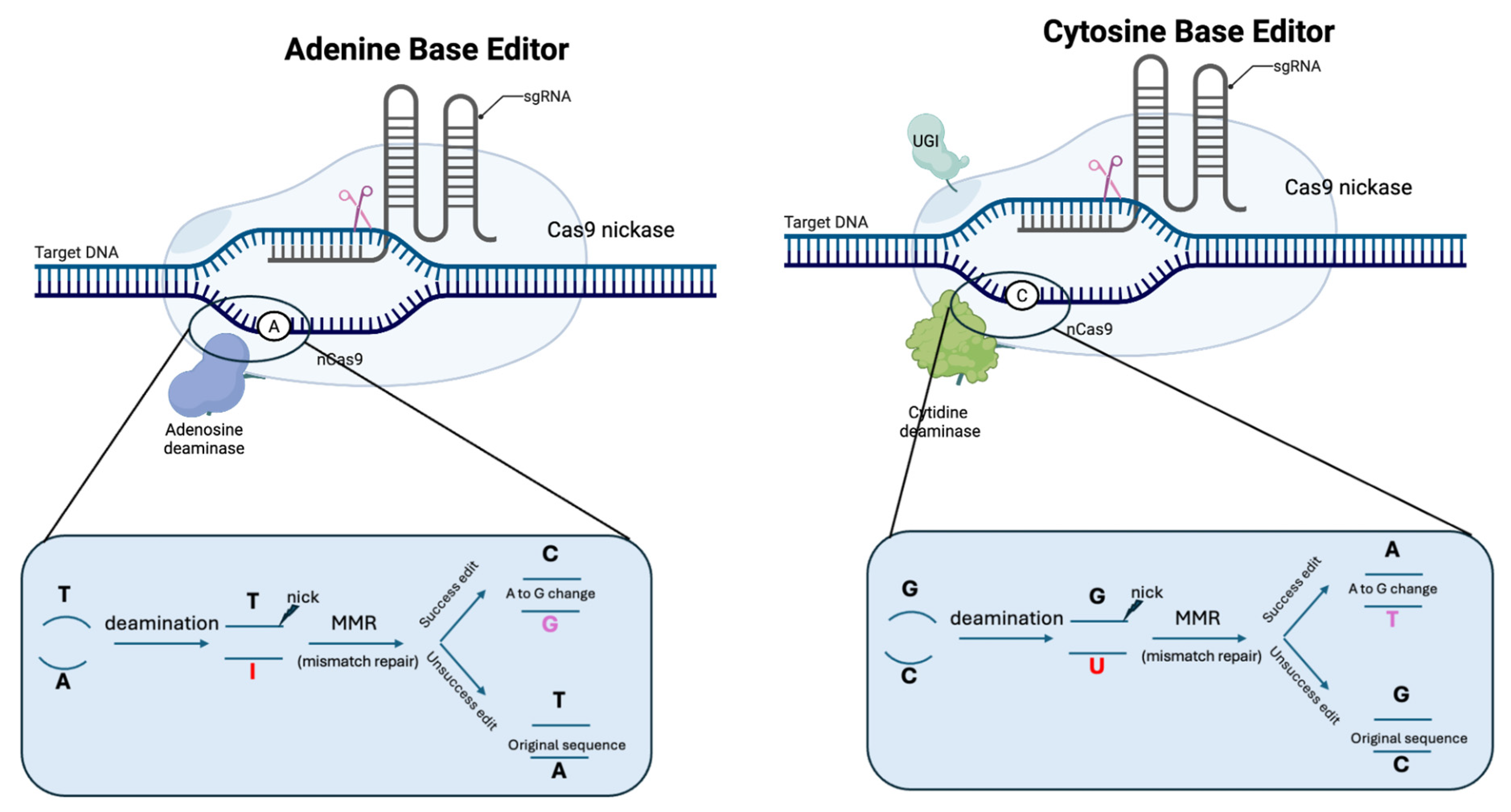

2.5. Base Editors

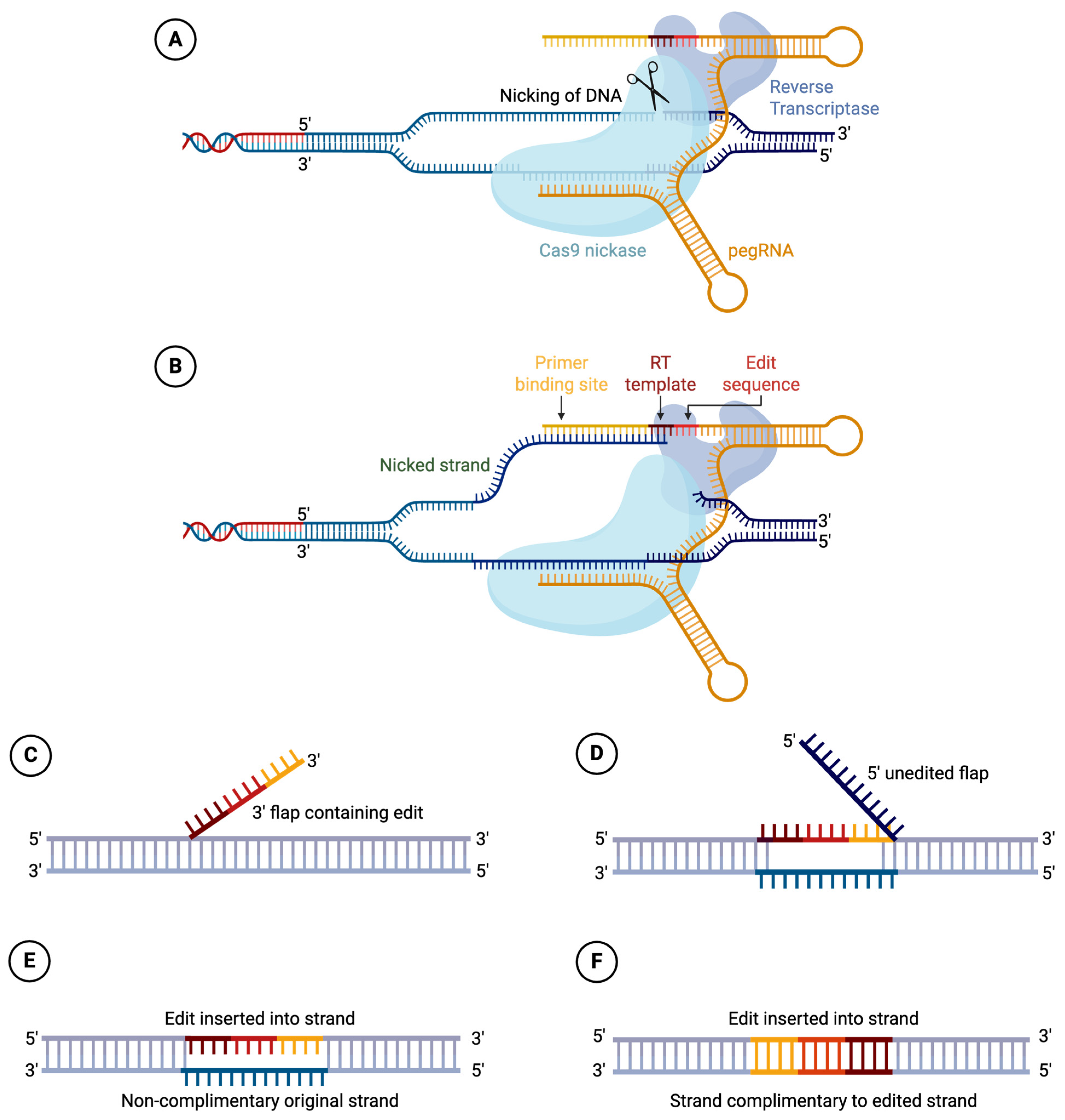

2.6. PRIME Editors

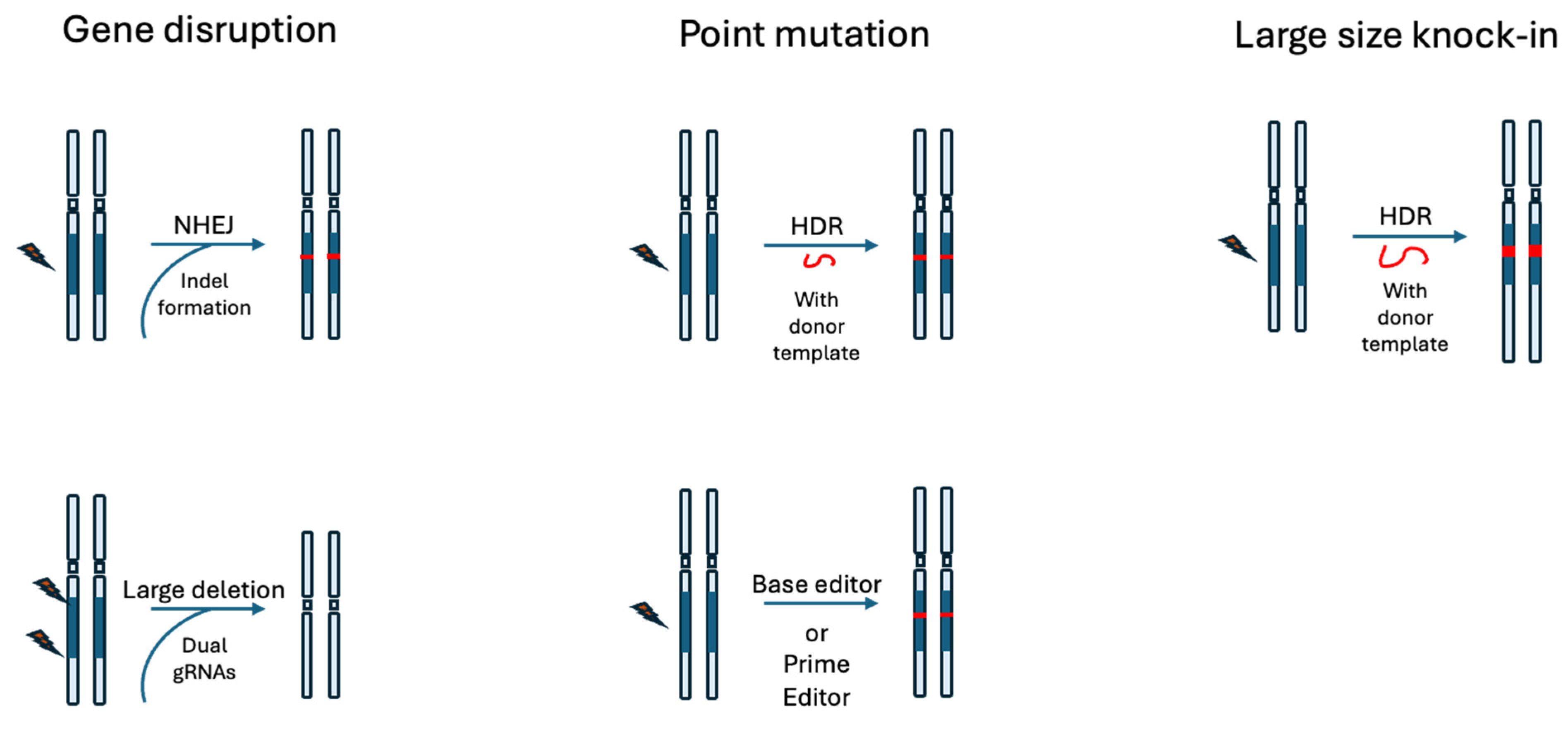

3. GETx Strategies

3.1. Gene Disruption

3.2. Point Mutation

3.3. Large-Scale Gene Knock-In

4. Delivery Considerations

4.1. Adeno-Associated Virus

4.2. Lentivirus

4.3. Adenovirus

4.4. Lipid Nanoparticles

4.5. Virus-Like Particles

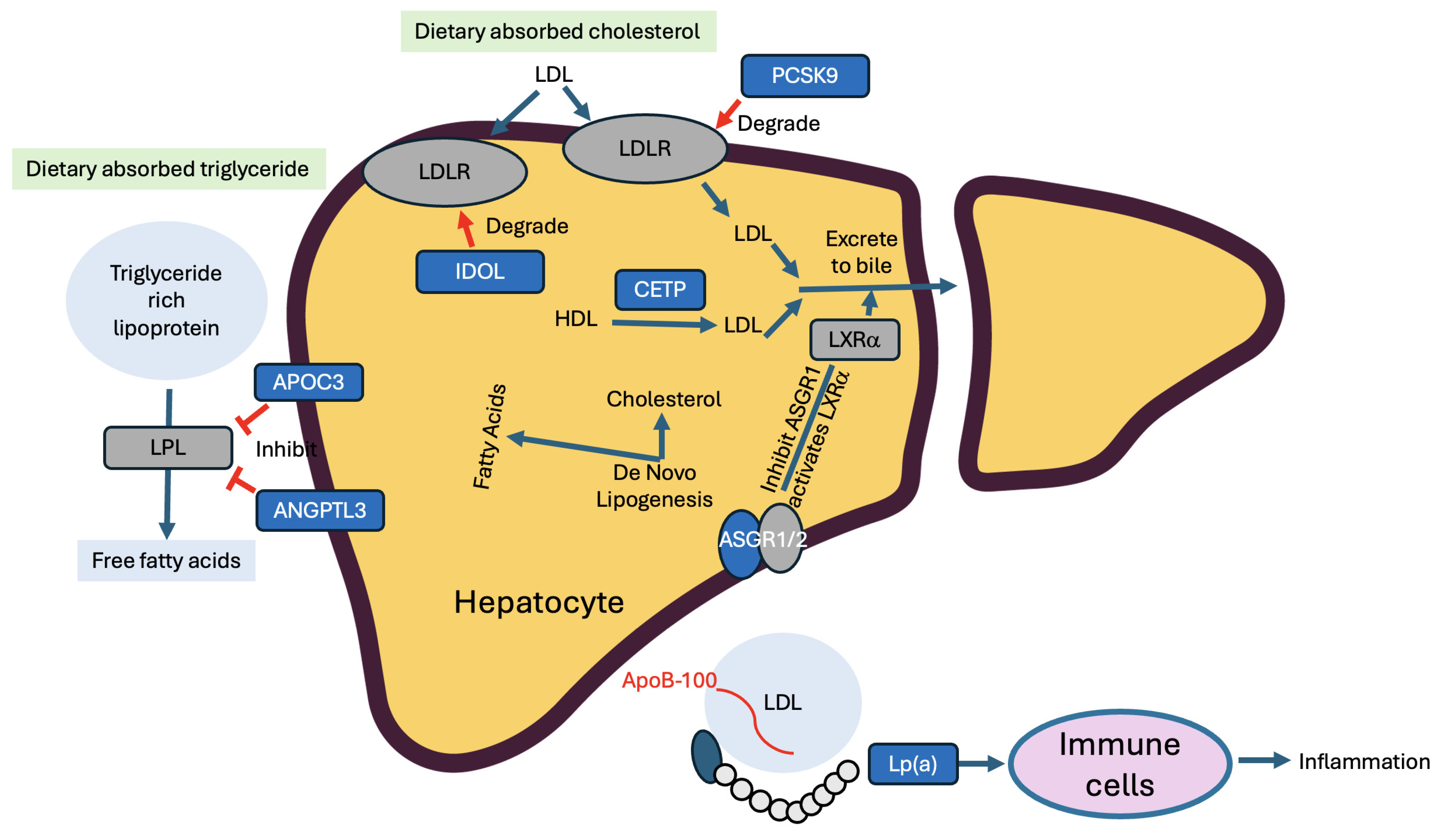

5. Genes of Interest in LivGETx-CVD

5.1. PCSK9

5.1.1. Rationale

5.1.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.1.3. Clinical Supporting Evidence (Other than LivGETx-CVD)

5.1.4. Ongoing LivGETx-CVD Clinical Trials Targeting PCSK9

5.1.5. Risk Considerations

5.2. ANGPTL3

5.2.1. Rationale

5.2.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.2.3. Clinical Supporting Evidence (Other than LivGETx-CVD)

5.2.4. Ongoing LivGETx-CVD Clinical Trials Targeting ANGPTL3

5.2.5. Risk Considerations

5.3. CETP

5.3.1. Rationale

5.3.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.3.3. Clinical Supporting Evidence

5.3.4. Risk Considerations

5.4. ApoC3

5.4.1. Rationale

5.4.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.4.3. Clinical Supporting Evidence (Other than LivGETx-CVD)

5.4.4. LivGETx-CVD Clinical Trials Targeting ApoC3

5.4.5. Risk Considerations

5.5. ASGR1

5.5.1. Rationale

5.5.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.5.3. Risk Considerations

5.6. LPA

5.6.1. Rationale

5.6.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.6.3. Clinical Supporting Evidence (Other than LivGETx-CVD)

5.6.4. Ongoing LivGETx-CVD Clinical Trials Targeting LPA

5.6.5. Risk Considerations

5.7. IDOL

5.7.1. Rationale

5.7.2. Preclinical Supporting Evidence

5.7.3. Risk Considerations

5.8. General Limitations of These Trials

| Trial | Company | Editor Type | Editing Target | Mutation Type | Delivery Method | Indication(s) | Phase/Status | Main Results/Outcomes (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VERVE-101 | Verve Therapeutics | Adenine base editor | PCSK9 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | HeFH | Phase 1b | Up to 55% LDL-C↓; durable PCSK9 KO; good safety [204] |

| VERVE-102 | Verve Therapeutics | Adenine base editor | PCSK9 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | HeFH, premature CAD | Phase 1b | Up to 69% LDL-C↓, 84% PCSK9↓; no treatment SAEs [205] |

| ART002 | AccurEdit Therapeutics | Canonical Cas9 nuclease | PCSK9 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | HeFH | Single-arm IIT complete | >50% LDL-C↓, good safety; triglyceride data not highlighted [120] |

| YOLT-101 | YolTech Therapeutics | Adenine base editor | PCSK9 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | HeFH | Phase 1 | 50% LDL-C↓, >70% PCSK9↓ at 4 months, mild transient events [206] |

| VERVE-201 | Verve Therapeutics | Adenine base editor | ANGPTL3 | Loss-of-function | GalNAc-LNP (IV) | RH, HoFH | Phase 1b Ongoing | Preclinical: 98–99% ANGPTL3↓; clinical data pending [207] |

| CTX310 | CRISPR Therapeutics | Canonical Cas9 nuclease | ANGPTL3 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | FH, SHTG, mixed dyslipidemia | Phase 1 | Up to 82% TG↓, up to 86% LDL-C↓, well-tolerated [208] |

| CS121 | Correctseq | Transformer base editor | APOC3 | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | FCS, severe hypertriglyceridemia | Phase 1 | Rapid TG↓ (initial patient); no adverse events; longer safety pending [209] |

| CTX320 | CRISPR Therapeutics | Canonical Cas9 nuclease | LPA | Loss-of-function | LNP (IV) | Elevated Lp(a), ASCVD/aortic stenosis | Phase 1 Ongoing | Preclinical: 95% Lp(a)↓; clinical data awaited [182] |

6. Challenges of LivGETx-CVD

6.1. Delivery Related Challenges

6.2. Off-Target Effect

6.3. On-Target Genotoxicity

6.4. Immunogenicity

6.5. Further Considerations

6.5.1. From Rare Disease to Prevention

6.5.2. Cost-Effectiveness and Feasibility

6.5.3. Ethical and Societal Questions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, R. Crispr Developers Win 2020 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2021, 185, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Gordon, T.; Kannel, W.B.; Castelli, W.P.; Dawber, T.R. Lipoproteins, cardiovascular disease, and death. The Framingham study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1981, 141, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Stone, N.J.; Ballantyne, C.; Bittner, V.; Criqui, M.H.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Goldberg, G.C.; Howard, W.J.; Jacobson, M.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; et al. Triglycerides and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2011, 123, 2292–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shahawy, M.; Cannon, C.P.; Blom, D.J.; McKenney, J.M.; Cariou, B.; Lecorps, G.; Pordy, R.; Chaudhari, U.; Colhoun, H.M. Efficacy and Safety of Alirocumab Versus Ezetimibe Over 2 Years (from ODYSSEY COMBO II). Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnier, M. Alirocumab for the treatment of hyperlipidemia in high-risk patients: An updated review. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2017, 15, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.A.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Sanganalmath, S.K.; Langslet, G.; Baum, S.J.; Shah, P.K.; Koren, A.; Mandel, J.; Davidson, M.H. Efficacy and Safety of Alirocumab in High-Risk Patients with Clinical Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and/or Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (from 5 Placebo-Controlled ODYSSEY Trials). Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 121, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.M. One-Shot, One Cure with Genome Editing for Dyslipidemia. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2014, 7, 967–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiga, M.; Qi, L.S.; Wu, J.C. Therapeutic genome editing in cardiovascular diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 168, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ren, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.E. Gene editing therapy ready for cardiovascular diseases: Opportunities, challenges, and perspectives. Med. Rev. 2021, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A. A CRISPR edit for heart disease. Nature 2018, 555, S23–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, F.V.; Link, W.; Ferreira, B.I. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing: From basic research to translational medicine. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 3766–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yan, Y.; Su, F.; Huang, X.; Xia, D.; Jiang, X.; Dong, Y.; Lv, P.; Chen, F.; Lv, Y. Research progress in gene editing technology. Front. Biosci. 2021, 26, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cao, D.; Han, R. Recent advances in therapeutic gene-editing technologies. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2619–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Cha, J.; Chandrasegaran, S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: Zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.C.; Tan, S.; Qiao, G.; A Barlow, K.; Wang, J.; Xia, D.F.; Meng, X.; E Paschon, D.; Leung, E.; Hinkley, S.J.; et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 29, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M.; Cermak, T.; Doyle, E.L.; Schmidt, C.; Zhang, F.; Hummel, A.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Voytas, D.F. Targeting DNA Double-Strand Breaks with TAL Effector Nucleases. Genetics 2010, 186, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, J.; Scholze, H.; Schornack, S.; Landgraf, A.; Hahn, S.; Kay, S.; Lahaye, T.; Nickstadt, A.; Bonas, U. Breaking the Code of DNA Binding Specificity of TAL-Type III Effectors. Science 2009, 326, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscou, M.J.; Bogdanove, A.J. A Simple Cipher Governs DNA Recognition by TAL Effectors. Science 2009, 326, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.D.; Richardson, C.D.; Corn, J.E. Advances in genome editing through control of DNA repair pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Packer, M.S.; Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudelli, N.M.; Komor, A.C.; Rees, H.A.; Packer, M.S.; Badran, A.H.; Bryson, D.I.; Liu, D.R. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 2017, 551, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.C.; Zhao, K.T.; Packer, M.S.; Gaudelli, N.M.; Waterbury, A.L.; Koblan, L.W.; Kim, Y.B.; Badran, A.H.; Liu, D.R. Improved base excision repair inhibition and bacteriophage Mu Gam protein yields C:G-to-T:A base editors with higher efficiency and product purity. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, eaao4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koblan, L.W.; Doman, J.L.; Wilson, C.; Levy, J.M.; Tay, T.; A Newby, G.; Maianti, J.P.; Raguram, A.; Liu, D.R. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Xin, X.; Hu, M.; Price, M.A.; Rosser, S.J.; Bi, C.; Zhang, X. Glycosylase base editors enable C-to-A and C-to-G base changes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 39, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Hong, M.; Luan, C.; Gao, H.; Ru, G.; Guo, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Wu, J.; et al. Adenine transversion editors enable precise, efficient A•T-to-C•G base editing in mammalian cells and embryos. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 42, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Ma, Q.; Wu, D.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; et al. Programmable A-to-Y base editing by fusing an adenine base editor with an N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Liu, D.R. Prime editing for precise and highly versatile genome manipulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 24, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, F.; Gao, G. CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Genome Editing: Strategies and In Vivo Delivery by AAV Vectors. Cell 2020, 181, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Stein, D.; Tang, W.W.; Frank, I.; Wang, S.Q.; Lee, G.; Spratt, S.K.; Surosky, R.T.; Giedlin, M.A.; Nichol, G.; et al. Gene Editing of CCR5 in Autologous CD4 T Cells of Persons Infected with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtmauer, E.A.; Fraietta, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Cohen, A.D.; Weber, K.L.; Lancaster, E.; Mangan, P.A.; Kulikovskaya, I.; Gupta, M.; Chen, F.; et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science 2020, 367, eaba7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xue, J.; Deng, T.; Zhou, X.; Yu, K.; Deng, L.; Huang, M.; Yi, X.; Liang, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Safety and feasibility of CRISPR-edited T cells in patients with refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.A.; Hemez, C.; Lei, L.; Traore, S.; Kulhankova, K.; Newby, G.A.; Doman, J.L.; Oye, K.; Pandey, S.; Karp, P.H.; et al. Systematic optimization of prime editing for the efficient functional correction of CFTR F508del in human airway epithelial cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 9, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N.E.; Suzuki, S.; Barillà, C.; Hawkins, F.J.; Randell, S.H.; Reynolds, S.D.; Stripp, B.R.; Davis, B.R. Correction of Airway Stem Cells: Genome Editing Approaches for the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everette, K.A.; Newby, G.A.; Levine, R.M.; Mayberry, K.; Jang, Y.; Mayuranathan, T.; Nimmagadda, N.; Dempsey, E.; Li, Y.; Bhoopalan, S.V.; et al. Ex vivo prime editing of patient haematopoietic stem cells rescues sickle-cell disease phenotypes after engraftment in mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.T.; Rayner, R.E.; Nouri, R.; Suarez, C.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kanke, K.L.; Vetter, T.A.; Cormet-Boyaka, E.; Vaidyanathan, S. DNA-PKcs inhibition improves sequential gene insertion of the full-length CFTR cDNA in airway stem cells. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Johnson, W.A.; Qu, Y.; Yin, D.; Ramkissoon, N.; Xiang, H.; Cong, L. Long sequence insertion via CRISPR/Cas gene-editing with transposase, recombinase, and integrase. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 28, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, J.; Yun, S.; Xue, C.; Yao, Y.; Rao, S. Recent advances in CRISPR-Cas9-based genome insertion technologies. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-Y.; Fan, P.-D.; Frizzell, R.A. Quantitative Analysis of the Packaging Capacity of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus. Hum. Gene Ther. 1996, 7, 2101–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, F.; Schmidt, K.; Kleinschmidt, J.A. A viral assembly factor promotes AAV2 capsid formation in the nucleolus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10220–10225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, P.J.; Kelsic, E.D.; Sinai, S.; Church, G.M. Comprehensive AAV capsid fitness landscape reveals a viral gene and enables machine-guided design. Science 2019, 366, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; A Wellman, J.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65 -mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelas, C.; Grimm, D. Split Cas9, Not Hairs − Advancing the Therapeutic Index of CRISPR Technology. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1700432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.M.; Yeh, W.-H.; Pendse, N.; Davis, J.R.; Hennessey, E.; Butcher, R.; Koblan, L.W.; Comander, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, D.R. Cytosine and adenine base editing of the brain, liver, retina, heart and skeletal muscle of mice via adeno-associated viruses. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, N.E.; Tasfaout, H.; Chamberlain, J.S. The road toward AAV-mediated gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimasu, H.; Cong, L.; Yan, W.X.; Ran, F.A.; Zetsche, B.; Li, Y.; Kurabayashi, A.; Ishitani, R.; Zhang, F.; Nureki, O. Crystal Structure of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell 2015, 162, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edraki, A.; Mir, A.; Ibraheim, R.; Gainetdinov, I.; Yoon, Y.; Song, C.-Q.; Cao, Y.; Gallant, J.; Xue, W.; Rivera-Pérez, J.A.; et al. A Compact, High-Accuracy Cas9 with a Dinucleotide PAM for In Vivo Genome Editing. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 714–726.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Koo, T.; Park, S.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, K.; Cho, H.-Y.; Song, D.W.; Lee, K.J.; Jung, M.H.; Kim, S.; et al. In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Gao, N.; Li, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, D.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Ong, S.-G.; et al. A compact Cas9 ortholog from Staphylococcus Auricularis (SauriCas9) expands the DNA targeting scope. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D. Lethal immunotoxicity in high-dose systemic AAV therapy. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 3123–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-S.; Agbandje-McKenna, M. Mapping the AAV Capsid Host Antibody Response toward the Development of Second Generation Gene Delivery Vectors. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.T.; Yu, Q.-C.; Wilson, J.M.; Croyle, M.A. Utility of PEGylated recombinant adeno-associated viruses for gene transfer. J. Control. Release 2005, 108, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.; Gessler, D.J.; Xie, J.; Zhong, L.; Li, J.; Tran, K.; Van Vliet, K.; Ren, L.; Su, Q.; et al. A Rationally Engineered Capsid Variant of AAV9 for Systemic CNS-Directed and Peripheral Tissue-Detargeted Gene Delivery in Neonates. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2018, 9, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, L.V.; Klinc, K.A.; Madigan, V.J.; Castellanos Rivera, R.M.; Wells, L.F.; Havlik, L.P.; Smith, J.K.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Asokan, A. Structure-guided evolution of antigenically distinct adeno-associated virus variants for immune evasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4812–E4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Thompson, A.A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Porter, J.B.; Thrasher, A.J.; Hongeng, S.; Sauer, M.G.; Thuret, I.; Lal, A.; Walters, M.C.; et al. Betibeglogene Autotemcel Gene Therapy for Non–β0/β0 Genotype β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.I.; Mallhi, K.K.; Ganesh, J.; Chen, W.-L. Elivaldogene autotemcel approved for treatment of cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (CALD) in males: A therapeutics bulletin of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. Open 2023, 1, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangji, R.N.; Abu Ali, Q.; Dhamija, R.; Corado, A.M.; Kharbanda, S. Lenmeldy (atidarsagene autotemcel) for individuals with early metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD): A therapeutics bulletin of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. Open 2025, 3, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J.; Walters, M.C.; Krishnamurti, L.; Mapara, M.Y.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Rifkin-Zenenberg, S.; Aygun, B.; Kasow, K.A.; Pierciey, F.J.; Bonner, M.; et al. Biologic and Clinical Efficacy of LentiGlobin for Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G.D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kasamon, Y.L.; Lin, X.; Xu, Z.; Theoret, M.R.; Purohit-Sheth, T. FDA Approval Summary: Axicabtagene Ciloleucel for Second-Line Treatment of Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 4331–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchkouj, N.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Przepiorka, D.; Xu, Z.; Purohit-Sheth, T.; Theoret, M. FDA Approval Summary: Brexucabtagene Autoleucel for Treatment of Adults with Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Oncologist 2022, 27, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, K.; Mahat, U.; Richardson, N.C.; Tegenge, M.; Gao, Q.; Theoret, M.R.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.A. FDA Approval Summary: Lisocabtagene Maraleucel for Relapsed or Refractory Follicular Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 3830–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanisch, K.; Yáñez-Muñoz, R.J. Integration-deficient Lentiviral Vectors: A Slow Coming of Age. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1316–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kymäläinen, H.; Appelt, J.U.; Giordano, F.A.; Davies, A.F.; Ogilvie, C.M.; Ahmed, S.G.; Laufs, S.; Schmidt, M.; Bode, J.; Yáñez-Muñoz, R.J.; et al. Long-Term Episomal Transgene Expression from Mitotically Stable Integration-Deficient Lentiviral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, H.A.; Danel, C.; Longenecker, G.; Metzger, M.; Setoguchi, Y.; Rosenfeld, M.A.; Gant, T.W.; Thorgeirsson, S.S.; Stratford-Perricaudet, L.D.; Perricaudet, M.; et al. Adenovirus–mediated in vivo gene transfer and expression in normal rat liver. Nat. Genet. 1992, 1, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, M.A.; Yoshimura, K.; Trapnell, B.C.; Yoneyama, K.; Rosenthal, E.R.; Dalemans, W.; Fukayama, M.; Bargon, J.; Stier, L.E.; Stratford-Perricaudet, L.; et al. In vivo transfer of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene to the airway epithelium. Cell 1992, 68, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, S.E.; Chirmule, N.; Lee, F.S.; Wivel, N.A.; Bagg, A.; Gao, G.-P.; Wilson, J.M.; Batshaw, M.L. Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003, 80, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumahara, K.; Nagata, H.; Watanabe, K.; Shimizu, N.; Arimoto, Y.; Isoyama, K.; Okamoto, Y.; Shirasawa, H. Suppression of inflammation by dexamethasone prolongs adenoviral vector-mediated transgene expression in murine nasal mucosa. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2005, 125, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, C.R.; Lachapelle, A.; Delgado, C.; Parkes, V.; Wadsworth, S.C.; Smith, A.E.; Francis, G.E. PEGylation of Adenovirus with Retention of Infectivity and Protection from Neutralizing Antibody In Vitro and In Vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M.A.; Gu, M.; Motzel, S.; Zhao, J.; Lin, J.; Su, Q.; Allen, H.; Franlin, L.; Parks, R.J.; Graham, F.L.; et al. An adenoviral vector deleted for all viral coding sequences results in enhanced safety and extended expression of a leptin transgene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7866–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, P.; Yu, S.-Y.; Thomson, S.B.; Birkenshaw, A.; Leavitt, B.R.; Ross, C.J.D. Lipid-Nanoparticle-Based Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Genome-Editing Components. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, G.; Querbes, W.; Alabi, C.; Eltoukhy, A.; Sarkar, S.; Zurenko, C.; Karagiannis, E.; Love, K.; Chen, D.; Zoncu, R.; et al. Efficiency of siRNA delivery by lipid nanoparticles is limited by endocytic recycling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Tsuzuku, T.; Takahashi, S.; Okamoto, A.; Dewa, T.; Nango, M.; Hyodo, K.; Ishihara, H.; Kikuchi, H.; Oku, N. Cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 444, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; De Smedt, S.C.; De Vos, W.H.; Braeckmans, K. Light-triggered nanocarriers for nucleic acid delivery. Drug Deliv. 2025, 32, 2502346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urits, I.; Swanson, D.; Swett, M.C.; Patel, A.; Berardino, K.; Amgalan, A.; Berger, A.A.; Kassem, H.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O. A Review of Patisiran (ONPATTRO®) for the Treatment of Polyneuropathy in People with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 9, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Marc, G.P.; Moreira, E.D.; Gruber, W.C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Stephen, S.; Nadine, R.; Zaks, T.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, M.; Sayyah, M.; Eshraghi, H.R.; Panahi, N.; Mirzapourdelavar, H.; Pourbadie, H.G. The Lentiviral Vector Pseudotyped by Modified Rabies Glycoprotein Does Not Cause Reactive Gliosis and Neurodegeneration in Rat Hippocampus. Iran. Biomed. J. 2019, 23, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frietze, K.M.; Peabody, D.S.; Chackerian, B. Engineering virus-like particles as vaccine platforms. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 18, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banskota, S.; Raguram, A.; Suh, S.; Du, S.W.; Davis, J.R.; Choi, E.H.; Wang, X.; Nielsen, S.C.; Newby, G.A.; Randolph, P.B.; et al. Engineered virus-like particles for efficient in vivo delivery of therapeutic proteins. Cell 2022, 185, 250–265.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Raguram, A.; Du, S.W.; Banskota, S.; Davis, J.R.; Newby, G.A.; Chen, P.Z.; Palczewski, K.; Liu, D.R. Engineered virus-like particles for transient delivery of prime editor ribonucleoprotein complexes in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguram, A.; An, M.; Chen, P.Z.; Liu, D.R. Directed evolution of engineered virus-like particles with improved production and transduction efficiencies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Arora, K.; Roy, S.S.; Joseph, A.; Rastogi, R.; Arora, N.M.; Kundu, P.K. Platforms, advances, and technical challenges in virus-like particles-based vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1123805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassoury, N.; Blasiole, D.A.; Oler, A.T.; Benjannet, S.; Hamelin, J.; Poupon, V.; McPherson, P.S.; Attie, A.D.; Prat, A.; Seidah, N.G. The Cellular Trafficking of the Secretory Proprotein Convertase PCSK9 and Its Dependence on the LDLR. Traffic 2007, 8, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.-W.; Schmidt, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, S.; Lin, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Beyer, T.P.; Bensch, W.R.; Li, W.; et al. Secreted PCSK9 downregulates low density lipoprotein receptor through receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.-H.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Dong, L.-W.; Li, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Li, W.-H.; Wang, J.-Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. New Loss-of-Function Mutations in PCSK9 Reduce Plasma LDL Cholesterol. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.C.; Boerwinkle, E.; Mosley, T.H.; Hobbs, H.H. Sequence Variations inPCSK9,Low LDL, and Protection against Coronary Heart Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Strong, A.; Patel, K.M.; Ng, S.-L.; Gosis, B.S.; Regan, S.N.; Cowan, C.A.; Rader, D.J.; Musunuru, K. Permanent Alteration of PCSK9 with In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Raghavan, A.; Chen, T.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Musunuru, K. CRISPR-Cas9 Targeting of PCSK9 in Human Hepatocytes In Vivo—Brief Report. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.C.; Wang, X.; Musunuru, K. In Vivo Base Editing of PCSK9 (Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9) as a Therapeutic Alternative to Genome Editing. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A.; Cong, L.; Yan, W.X.; Scott, D.A.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Kriz, A.J.; Zetsche, B.; Shalem, O.; Wu, X.; Makarova, K.S.; et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 2015, 520, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Su, J.; Liu, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhong, X.; Mo, L.; Wang, Q.; Deng, H.; Yang, Y. In vivo PCSK9 gene editing using an all-in-one self-cleavage AAV-CRISPR system. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 20, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelluti, M.A.; Poeta, V.M.; Valsoni, S.; Quarato, P.; Merlin, S.; Merelli, I.; Lombardo, A. Durable and efficient gene silencing in vivo by hit-and-run epigenome editing. Nature 2024, 627, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, F.; Xiong, Q.; Shah, S.S.; Ko, C.-W.; Kelly, K.; Morrison, M.S.; Giancarlo, C.; Ramirez, R.N.; Hildebrand, E.M.; Voytek, S.B.; et al. A potent epigenetic editor targeting human PCSK9 for durable reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Breton, C.; Warzecha, C.C.; Bell, P.; Yan, H.; He, Z.; White, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Buza, E.L.; et al. Long-term stable reduction of low-density lipoprotein in nonhuman primates following in vivo genome editing of PCSK9. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2019–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musunuru, K.; Chadwick, A.C.; Mizoguchi, T.; Garcia, S.P.; DeNizio, J.E.; Reiss, C.W.; Wang, K.; Iyer, S.; Dutta, C.; Clendaniel, V.; et al. In vivo CRISPR base editing of PCSK9 durably lowers cholesterol in primates. Nature 2021, 593, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgangl, T.; Dennis, M.K.; Lin, P.J.; Oka, R.; Witzigmann, D.; Villiger, L.; Qi, W.; Hruzova, M.; Kissling, L.; Schwank, G.; et al. In vivo adenine base editing of PCSK9 in macaques reduces LDL cholesterol levels. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.G.; Mazzola, A.M.; Braun, M.C.; Platt, C.; Vafai, S.B.; Kathiresan, S.; Rohde, E.; Bellinger, A.M.; Khera, A.V. Efficacy and Safety of an Investigational Single-Course CRISPR Base-Editing Therapy Targeting PCSK9 in Nonhuman Primate and Mouse Models. Circulation 2023, 147, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Yu, Z.; Ding, L.; Lu, Z.; Yao, K.; Zhang, H.; Huang, B.; He, M.; Ma, L. Improved split prime editors enable efficient in vivo genome editing. Cell Rep. 2024, 44, 115144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.G.; Farnier, M.; Krempf, M.; Bergeron, J.; Luc, G.; Averna, M.; Stroes, E.S.; Langslet, G.; Raal, F.J.; El Shahawy, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Alirocumab in Reducing Lipids and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, D.J.; Hala, T.; Bolognese, M.; Lillestol, M.J.; Toth, P.D.; Burgess, L.; Ceska, R.; Roth, E.; Koren, M.J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; et al. A 52-Week Placebo-Controlled Trial of Evolocumab in Hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Wright, R.S.; Kallend, D.; Koenig, W.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; Bisch, J.A.; Richardson, T.; Jaros, M.; Wijngaard, P.L.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Inclisiran in Patients with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Yao, Z.; Han, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Xu, G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ongericimab in Chinese patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Atherosclerosis 2025, 403, 119120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Q.; Du, W.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, T.; Deng, H.; Qian, L.; Zheng, S.; Cui, Y. Pharmacokinetic/LDL-C and exposure–response analysis of tafolecimab in Chinese hypercholesterolemia patients: Results from phase I, II, and III studies. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 16, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pei, Z.; Chen, B.; Qu, Y.; Dong, X.; Yu, B.; Wang, G.; Xu, F.; Lu, D.; He, Z.; et al. Ebronucimab in Chinese patients with hypercholesterolemia—A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ebronucimab. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 207, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lv, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, R.; Gao, X.; Han, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zheng, M.; Luo, S.; et al. Recaticimab as Add-On Therapy to Statins for Nonfamilial Hypercholesterolemia. JACC 2024, 84, 2037–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofherr, A.; Schumi, J.; Rekić, D.; Knöchel, J.; Nilsson, C.; Rudvik, A.; Hurt-Camejo, E.; Wernevik, L.; Rydén-Bergsten, T.; Koren, M.; et al. ETESIAN: A phase 2B study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of AZD8233, a PCSK9-targeted antisense oligonucleotide, in patients with dyslipidemia. Atherosclerosis 2022, 355, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribo Showcases New Clinical Data from Leading siRNA Programs at ESC 2025, Underscoring Significant Progress and Achievements in Advancing Cardiovascular Therapies. Available online: https://www.ribolia.com/en/media-center/our-products-news/50?utm_source (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Klug, E.Q.; Llerena, S.; Burgess, L.J.; Fourie, N.; Scott, R.; Vest, J.; Caldwell, K.; Kallend, D.; Stein, E.A.; The LIBERATE-HR Investigators; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lerodalcibep in Patients with or at High Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.R.; Hooper, A.J. MK-0616: An oral PCSK9 inhibitor for hypercholesterolemia treatment. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2023, 32, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, M.J.; Descamps, O.; Hata, Y.; Hengeveld, E.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ikonomidis, I.; Jensen, M.D.R.J.; Langbakke, I.H.; Martens, F.M.A.C.; Søndergaard, A.L.; et al. PCSK9 inhibition with orally administered NNC0385-0434 in hypercholesterolaemia: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R.; Garkaviy, P.; Knöchel, J.; Barbour, A.; Rudvik, A.; Laru, J.; Twaddle, L.; Mccarthy, M.C.; Rosenmeier, J.B. AZD0780, the first oral small molecule PCSK9 inhibitor for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia: Results from a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 trial. Atherosclerosis 2024, 395, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verve Therapeutics Announces Positive Initial Data from the Heart-2 Phase 1b Clinical Trial of VERVE-102, an In Vivo Base Editing Medicine Targeting PCSK9. Available online: https://vervetx.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/verve-therapeutics-announces-positive-initial-data-heart-2-phase (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- World’s First: In Vivo Gene Editing Product ART002 Achieves Saturation of Pharmacological Effect in Humans and Reduces LDL-C Safely and Effectively. Available online: https://www.accuredit.com/46/63 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Da Dalt, L.; Ruscica, M.; Bonacina, F.; Balzarotti, G.; Dhyani, A.; Di Cairano, E.; Baragetti, A.; Arnaboldi, L.; De Metrio, S.; Pellegatta, F.; et al. PCSK9 deficiency reduces insulin secretion and promotes glucose intolerance: The role of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Shi, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Kong, N.; Ji, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. PCSK9 potentiates innate immune response to RNA viruses by preventing AIP4-mediated polyubiquitination and degradation of VISA/MAVS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2412206122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connell, E.M.; Lohoff, F.W. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) in the Brain and Relevance for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Afroza, H.; Rader, D.J.; Jin, W. Angiopoietin-like Protein 3 Inhibits Lipoprotein Lipase Activity through Enhancing Its Cleavage by Proprotein Convertases. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 27561–27570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, F.E.; Gusarova, V.; Dunbar, R.L.; O’dUshlaine, C.; Schurmann, C.; Gottesman, O.; McCarthy, S.; Van Hout, C.V.; Bruse, S.; Dansky, H.M.; et al. Genetic and Pharmacologic Inactivation of ANGPTL3 and Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitziel, N.O.; Khera, A.V.; Wang, X.; Bierhals, A.J.; Vourakis, A.C.; Sperry, A.E.; Natarajan, P.; Klarin, D.; Emdin, C.A.; Zekavat, S.M.; et al. ANGPTL3 Deficiency and Protection Against Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2054–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.C.; Evitt, N.H.; Lv, W.; Musunuru, K. Reduced Blood Lipid Levels with In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Base Editing of ANGPTL3. Circulation 2018, 137, 975–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Glass, Z.; Chen, J.; Haas, M.; Jin, X.; Zhao, X.; Rui, X.; Ye, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Lipid nanoparticle-mediated codelivery of Cas9 mRNA and single-guide RNA achieves liver-specific in vivo genome editing of Angptl3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020401118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, W.; Herzog, R.W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.E.; Han, R. Liver-specific in vivo base editing of Angptl3 via AAV delivery efficiently lowers blood lipid levels in mice. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.R.; Wang, X.; Witte, I.P.; Huang, T.P.; Levy, J.M.; Raguram, A.; Banskota, S.; Seidah, N.G.; Musunuru, K.; Liu, D.R. Efficient in vivo base editing via single adeno-associated viruses with size-optimized genomes encoding compact adenine base editors. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirallah, J.; Bloomer, H.; Wich, D.; Huang, C.; Workman, J.N.; Li, Y.; Newby, G.A.; Liu, D.R.; Xu, Q. In vivo base editing of Angptl3 via lipid nanoparticles to treat cardiovascular disease. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehn, B.M. Evinacumab Approval Adds a New Option for Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia with a Hefty Price Tag. Circulation 2021, 143, 2494–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, F.J.; Rosenson, R.S.; Reeskamp, L.F.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kastelein, J.J.; Rubba, P.; Ali, S.; Banerjee, P.; Chan, K.-C.; Gipe, D.A.; et al. Evinacumab for Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenson, R.S.; George, R.T.; Sanchez, R.J.; Zhao, X.-Q.; Ponda, M.P.; Waldron, A.; Pordy, R. Efficacy of evinacumab in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia and a history of severe hypertriglyceridemia-related acute pancreatitis: A phase 2b trial. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenson, R.S.; Gaudet, D.; Hegele, R.A.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Nicholls, S.J.; Lucas, K.J.; Martin, J.S.; Zhou, R.; Muhsin, M.; Chang, T.; et al. Zodasiran, an RNAi Therapeutic Targeting ANGPTL3, for Mixed Hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, K.K.; Oru, E.; Rosenson, R.S.; Jones, J.; Ma, X.; Walgren, J.; Haupt, A.; Verma, S.; Gaudet, D.; Nicholls, S.J.; et al. Durability and efficacy of solbinsiran, a GalNAc-conjugated siRNA targeting ANGPTL3, in adults with mixed dyslipidaemia (PROLONG-ANG3): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, D.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Baum, S.J.; Hurh, E.; Kingsbury, J.; Bartlett, V.J.; Figueroa, A.L.; Piscitelli, P.; Singleton, W.; Witztum, J.L.; et al. Vupanorsen, an N-acetyl galactosamine-conjugated antisense drug to ANGPTL3 mRNA, lowers triglycerides and atherogenic lipoproteins in patients with diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and hypertriglyceridaemia. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3936–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffin, L.J.; Nicholls, S.J.; Scott, R.S.; Clifton, P.M.; Baker, J.; Sarraju, A.; Singh, S.; Wang, Q.; Wolski, K.; Xu, H.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Targeting ANGPTL3. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 2119–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarugi, P.; Bertolini, S.; Calandra, S. Angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) deficiency and familial combined hypolipidemia. J. Biomed. Res. 2019, 33, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Larsen, S.W.R.; Bondesen, S.; Qian, Y.; Tian, H.D.; Walker, S.G.; Davies, B.S.J.; Remaley, A.T.; Young, S.G.; Konrad, R.J.; et al. ANGPTL3/8 is an atypical unfoldase that regulates intravascular lipolysis by catalyzing unfolding of lipoprotein lipase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2420721122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall, A. Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J. Lipid Res. 1993, 34, 1255–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barter, P.J.; Nicholls, S.J.; Kastelein, J.J.; Rye, K.-A. Is cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition an effective strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk? CETP inhibition as a strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk: The pro case. Circulation 2015, 132, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Lauridsen, B.K.; Afzal, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Frikke-Schmidt, R.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A. Long-term Benefits and Harms Associated with Genetic Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Deficiency in the General Population. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millwood, I.Y.; Bennett, D.A.; Holmes, M.V.; Boxall, R.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Yang, L.; Sansome, S.; Chen, Y.; Du, H.; et al. Association of CETP Gene Variants with Risk for Vascular and Nonvascular Diseases Among Chinese Adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Niimi, M.; Yang, D.; Liang, J.; Xu, J.; Kimura, T.; Mathew, A.V.; Guo, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, T.; et al. Deficiency of Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Protects Against Atherosclerosis in Rabbits. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugano, M.; Makino, N.; Sawada, S.; Otsuka, S.; Watanabe, M.; Okamoto, H.; Kamada, M.; Mizushima, A. Effect of Antisense Oligonucleotides against Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein on the Development of Atherosclerosis in Cholesterol-fed Rabbits. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5033–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barter, P.J.; Caulfield, M.; Eriksson, M.; Grundy, S.M.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Komajda, M.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; Mosca, L.; Tardif, J.-C.; Waters, D.D.; et al. Effects of Torcetrapib in Patients at High Risk for Coronary Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2109–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Abt, M.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Barter, P.J.; Brumm, J.; Chaitman, B.R.; Holme, I.M.; Kallend, D.; Leiter, L.A.; et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2089–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HPS3/TIMI55–REVEAL Collaborative Group; Bowman, L.; Hopewell, J.C.; Chen, F.; Wallendszus, K.; Stevens, W.; Collins, R.; Wiviott, S.D.; Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E.; et al. Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients with Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Nicholls, S.J.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Barter, P.J.; Brewer, H.B.; Fox, K.A.A.; Gibson, C.M.; Granger, C.; Menon, V.; Montalescot, G.; et al. Evacetrapib and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Vascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Nelson, A.J.; Ditmarsch, M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Ray, K.K.; Navar, A.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Curcio, D.L.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Obicetrapib in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovingh, G.K.; Ray, K.K.; Boekholdt, S.M. Is Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Inhibition an Effective Strategy to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk? Circulation 2015, 132, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebara, T.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Steiner, G.; Shachter, N.S. Chylomicronemia due to apolipoprotein CIII overexpression in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Apolipoprotein CIII-induced hypertriglyceridemia is not mediated by effects on apolipoprotein E. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2672–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.A.; Smith, L.C.; Pownall, H.; Sparrow, J.T.; Nicolas, J.-P.; Gotto, A.M. Hydrolysis of phospholipids by purified milk lipoprotein lipase. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 291, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M. The crucial roles of apolipoproteins E and C-III in apoB lipoprotein metabolism in normolipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 26, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, M.; Zhong, S.; Khalil, M.B.; Links, P.H.; Zhao, Y.; Iqbal, J.; Hussain, M.M.; Parks, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Z. Expression of apolipoprotein C-III in McA-RH7777 cells enhances VLDL assembly and secretion under lipid-rich conditions. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 22–31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Soffer, G.; Sztalryd, C.; Horenstein, R.B.; Holleran, S.; Matveyenko, A.; Thomas, T.; Nandakumar, R.; Ngai, C.; Karmally, W.; Ginsberg, H.N.; et al. Effects of APOC3 Heterozygous Deficiency on Plasma Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Cong, N.X.; Gao, M.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Xian, X. Inactivation of ApoC3 by CRISPR/Cas9 Protects Against Atherosclerosis in Hamsters. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yan, K.; Zhuang, W.; Liang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of APOC3 stabilizes plasma lipids and inhibits atherosclerosis in rabbits. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, S.; Bucher, S.; Smekalova, E.; Saraya, J.; Stein, S.; Sato, A.; Bale, S.; Krupa, O.; Mauriello, A.; Ripley-Phipps, S.; et al. Abstract 4146303: A Single-Dose of a Novel CasX-Editor Lowers APOC3 Levels In Vivo. Circulation 2024, 150, A4146303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witztum, J.L.; Gaudet, D.; Freedman, S.D.; Alexander, V.J.; Digenio, A.; Williams, K.R.; Yang, Q.; Hughes, S.G.; Geary, R.S.; Arca, M.; et al. Volanesorsen and Triglyceride Levels in Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouni-Berthold, I.; Alexander, V.J.; Yang, Q.; Hurh, E.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Moriarty, P.M.; Hughes, S.G.; Gaudet, D.; A Hegele, R.; O’DEa, L.S.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of volanesorsen in patients with multifactorial chylomicronaemia (COMPASS): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.S.; Alexander, V.J.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Arca, M.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Soran, H.; Prohaska, T.A.; Xia, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; et al. Olezarsen, Acute Pancreatitis, and Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, G.F.; Rosenson, R.S.; Hegele, R.A.; Goldberg, I.J.; Gallo, A.; Mertens, A.; Baass, A.; Zhou, R.; Muhsin, M.; Hellawell, J.; et al. Plozasiran for Managing Persistent Chylomicronemia and Pancreatitis Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase 2 Trial Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of RBD5044 in Patients with Mixed Dyslipidemia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06797401 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Study of RN0361 in Adult Healthy Subjects and Adult Hypertriglyceridemic Subjects. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06471543?term=AREA%5BConditionSearch%5D(%22Familial%20Chylomicronemia%20Syndrome%22)&rank=6 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- A First in Human Study of STT-5058, an Antibody That Binds ApoC3. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04419688 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Khetarpal, S.A.; Zeng, X.; Millar, J.S.; Vitali, C.; Somasundara, A.V.H.; Zanoni, P.; Landro, J.A.; Barucci, N.; Zavadoski, W.J.; Sun, Z.; et al. A human APOC3 missense variant and monoclonal antibody accelerate apoC-III clearance and lower triglyceride-rich lipoprotein levels. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyose, C. Absorption, transportation, and distribution of vitamin E homologs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 177, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordts, P.L.; Nock, R.; Son, N.-H.; Ramms, B.; Lew, I.; Gonzales, J.C.; Thacker, B.E.; Basu, D.; Lee, R.G.; Mullick, A.E.; et al. ApoC-III inhibits clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins through LDL family receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2855–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwell, G.; Harford, J. Carbohydrate-Specific Receptors of the Liver. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1982, 51, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-Q.; Li, L.-L.; Hu, A.; Deng, G.; Wei, J.; Li, Y.-F.; Liu, Y.-B.; Lu, X.-Y.; Qiu, Z.-P.; Shi, X.-J.; et al. Inhibition of ASGR1 decreases lipid levels by promoting cholesterol excretion. Nature 2022, 608, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nioi, P.; Sigurdsson, A.; Thorleifsson, G.; Helgason, H.; Agustsdottir, A.B.; Norddahl, G.L.; Helgadottir, A.; Magnusdottir, A.; Jonasdottir, A.; Gretarsdottir, S.; et al. Variant ASGR1 Associated with a Reduced Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, B.; Zhou, J.; Du, M.; Xing, X.; Bai, L.; Liu, E.; Alvarez, F.; et al. Deficiency of ASGR1 in pigs recapitulates reduced risk factor for cardiovascular disease in humans. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Leng, X.K.; Zhai, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Z.W.; Xiao, J.Y.; Lu, J.F.; Liu, K.; Xia, B.; Gao, Q.; et al. Deficiency of ASGR1 promotes liver injury by increasing GP73-mediated hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Chapman, M.J.; Ray, K.; Borén, J.; Andreotti, F.; Watts, G.F.; Ginsberg, H.; Amarenco, P.; Catapano, A.; Descamps, O.S.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: Current status. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 2844–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Ference, B.A.; Staley, J.R.; Freitag, D.F.; Mason, A.M.; Nielsen, S.F.; Willeit, P.; Young, R.; Surendran, P.; Karthikeyan, S.; et al. Association of LPA Variants with Risk of Coronary Disease and the Implications for Lipoprotein(a)-Lowering Therapies: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; Wright, N.; Lin, K.; Yu, C.; Walters, R.G.; Lv, J.; Hill, M.; Kartsonaki, C.; Millwood, I.Y.; Bennett, D.A.; et al. Causal Relevance of Lp(a) for Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke Types in East Asian and European Ancestry Populations: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Circulation 2025, 151, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfler, A.M.; Park, S.H.; Assini, J.M.; Youssef, A.; Saxena, L.; Yaseen, A.B.; De Giorgi, M.; Chuecos, M.; Hurley, A.E.; Li, A.; et al. LPA disruption with AAV-CRISPR potently lowers plasma apo(a) in transgenic mouse model: A proof-of-concept study. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2022, 27, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.A.; Pierre, A.F.; Quirino, L.; Acharya, G.; Vasudevan, A.; Pei, Y.; Chung, E.; Chang, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Endow, M.; et al. Lipid nanoparticle delivery of TALEN mRNA targeting LPA causes gene disruption and plasma lipoprotein(a) reduction in transgenic mice. Mol. Ther. 2024, 33, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, P.K.; D’Souza, S.; Wood, T.; Gowda, V.; Lee, N.; Zhang, M.L.; Pandji, J.; Serwer, L.; Steiger, K.; Sula, E.; et al. Abstract 17013: CTX320: An Investigational in vivo CRISPR-Based Therapy Efficiently and Durably Reduces Lipoprotein (a) Levels in Non-Human Primates After a Single Dose. Circulation 2023, 148, A17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viney, N.J.; van Capelleveen, J.C.; Geary, R.S.; Xia, S.; A Tami, J.; Yu, R.Z.; Marcovina, S.M.; Hughes, S.G.; Graham, M.J.; Crooke, R.M.; et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): Two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet 2016, 388, 2239–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial Assessing the Impact of Lipoprotein(a) Lowering with Pelacarsen (TQJ230) on the Progression of Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis [Lp(a)FRONTIERS CAVS]. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05646381 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Investigate the Effect of Lepodisiran on the Reduction of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Adults with Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Who Have Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease or Are at Risk for a First Cardiovascular Event—ACCLAIM-Lp(a). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06292013 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Nissen, S.E.; Wang, Q.; Nicholls, S.J.; Navar, A.M.; Ray, K.K.; Schwartz, G.G.; Szarek, M.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Troquay, R.; Dorresteijn, J.A.N.; et al. Zerlasiran-A Small-Interfering RNA Targeting Lipoprotein(a): A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 332, 1992–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study Assessing the Impact of Olpasiran on Major Cardiovascular Events in Participants with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Lipoprotein(a). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05581303 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Michael, L.; Perez, C.; Lafuente, C.; Sanz, G.; Priego, J.; Escribano, A.; Calle, L.; Espinosa, J.; Sauder, M.; Priest, B.; et al. Discovery and preclinical development of LY3473329, a potent small molecule inhibitor of lipoprotein(a) formation. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, ehad655.2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Ni, W.; Rhodes, G.M.; Nissen, S.E.; Navar, A.M.; Michael, L.F.; Haupt, A.; Krege, J.H. Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglés-Cano, E.; Díaz, A.D.L.P.; Loyau, S. Inhibition of Fibrinolysis by Lipoprotein(a). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 936, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelcer, N.; Hong, C.; Boyadjian, R.; Tontonoz, P. LXR Regulates Cholesterol Uptake Through Idol-Dependent Ubiquitination of the LDL Receptor. Science 2009, 325, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.K.; Cook, E.C.L.; Loregger, A.; Hoeksema, M.A.; Scheij, S.; Kovacevic, I.; Hordijk, P.L.; Ovaa, H.; Zelcer, N. Deubiquitylase Inhibition Reveals Liver X Receptor-independent Transcriptional Regulation of the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase IDOL and Lipoprotein Uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 4813–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Duit, S.; Jalonen, P.; Out, R.; Scheer, L.; Sorrentino, V.; Boyadjian, R.; Rodenburg, K.W.; Foley, E.; Korhonen, L.; et al. The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase IDOL Induces the Degradation of the Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Family Members VLDLR and ApoER2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19720–19726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, E.; Hong, C.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Tu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zelcer, N.; Boyadjian, R.; de Jong, P.J.; Young, S.G.; Fong, L.G.; et al. Targeted Disruption of the Idol Gene Alters Cellular Regulation of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor by Sterols and Liver X Receptor Agonists. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.K.; Laufs, U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasman, D.I.; Paré, G.; Mora, S.; Hopewell, J.C.; Peloso, G.; Clarke, R.; Cupples, L.A.; Hamsten, A.; Kathiresan, S.; Mälarstig, A.; et al. Forty-Three Loci Associated with Plasma Lipoprotein Size, Concentration, and Cholesterol Content in Genome-Wide Analysis. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslovich, T.M.; Musunuru, K.; Smith, A.V.; Edmondson, A.C.; Stylianou, I.M.; Koseki, M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ripatti, S.; Chasman, D.I.; Willer, C.J.; et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010, 466, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissglas-Volkov, D.; Calkin, A.C.; Tusie-Luna, T.; Sinsheimer, J.S.; Zelcer, N.; Riba, L.; Tino, A.M.V.; Ordoñez-Sánchez, M.L.; Cruz-Bautista, I.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; et al. The N342S MYLIP polymorphism is associated with high total cholesterol and increased LDL receptor degradation in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3062–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, V.; Fouchier, S.W.; Motazacker, M.M.; Nelson, J.K.; Defesche, J.C.; Dallinga-Thie, G.M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Hovingh, G.K.; Zelcer, N. Identification of a loss-of-function inducible degrader of the low-density lipoprotein receptor variant in individuals with low circulating low-density lipoprotein. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Marshall, S.M.; McDaniel, A.L.; Graham, M.; Layne, J.D.; Cai, L.; Scotti, E.; Boyadjian, R.; Kim, J.; Chamberlain, B.T.; et al. The LXR–Idol Axis Differentially Regulates Plasma LDL Levels in Primates and Mice. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, T.; Koike, Y.; Niimi, M.; Guo, Y.; Yang, D.; Song, J.; Xu, J.; Tang, X.; Ren, Z.; Kong, X.; et al. IDOL Deficiency Inhibits Cholesterol-Rich Diet–Induced Atherosclerosis in Rabbits. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.D.; Priest, C.; Bjursell, M.; Gao, J.; Arneson, D.V.; Ahn, I.S.; Diamante, G.; van Veen, J.E.; Massa, M.G.; Calkin, A.C.; et al. IDOL regulates systemic energy balance through control of neuronal VLDLR expression. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Marosi, M.; Choi, J.; Achiro, J.M.; Kim, S.; Li, S.; Otis, K.; Martin, K.C.; Portera-Cailliau, C.; Tontonoz, P. The E3 ubiquitin ligase IDOL regulates synaptic ApoER2 levels and is important for plasticity and learning. eLife 2017, 6, e29178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Qin, X.; Kong, F.; Chen, P.; Pan, G. Improving cellular uptake of therapeutic entities through interaction with components of cell membrane. Drug Deliv. 2019, 26, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdosi, S.R.; Ewaisha, R.; Moghadam, F.; Krishna, S.; Park, J.G.; Ebrahimkhani, M.R.; Kiani, S.; Anderson, K.S. Multifunctional CRISPR-Cas9 with engineered immunosilenced human T cell epitopes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wienert, B.; Shin, J.; Zelin, E.; Pestal, K.; E Corn, J. In vitro–transcribed guide RNAs trigger an innate immune response via the RIG-I pathway. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, L.E.; Fisher, J.; O’Rourke, K.P.; Muley, A.; Kastenhuber, E.R.; Livshits, G.; Tschaharganeh, D.F.; Socci, N.D.; Lowe, S.W. Inducible in vivo genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, L.; Mao, S.; Sheng, J.; Chen, L.; Khan, U.; Upputuri, P.K.; Zakharov, Y.N.; Coughlan, M.F.; et al. Near-infrared light activatable chemically induced CRISPR system. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalter, N.; Fuster-García, C.; Silva, A.; Ronco-Díaz, V.; Roncelli, S.; Turchiano, G.; Gorodkin, J.; Cathomen, T.; Benabdellah, K.; Lee, C.; et al. Off-target effects in CRISPR-Cas genome editing for human therapeutics: Progress and challenges. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Joung, J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, I.M.; Gao, L.; Zetsche, B.; Scott, D.A.; Yan, W.X.; Zhang, F. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 2016, 351, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulskas, C.A.; Dever, D.P.; Rettig, G.R.; Turk, R.; Jacobi, A.M.; Collingwood, M.A.; Bode, N.M.; McNeill, M.S.; Yan, S.; Camarena, J.; et al. A high-fidelity Cas9 mutant delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex enables efficient gene editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, A.; Olivieri, M.; Petris, G.; Montagna, C.; Reginato, G.; Maule, G.; Lorenzin, F.; Prandi, D.; Romanel, A.; Demichelis, F.; et al. A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klermund, J.; Rhiel, M.; Kocher, T.; Chmielewski, K.O.; Bischof, J.; Andrieux, G.; el Gaz, M.; Hainzl, S.; Boerries, M.; Cornu, T.I.; et al. On- and off-target effects of paired CRISPR-Cas nickase in primary human cells. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 1298–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Sander, J.D.; Reyon, D.; Cascio, V.M.; Joung, J.K. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Ryan, D.; Taussig, D.; Steinfeld, I.; Phadnis, S.M.; Lunstad, B.D.; Singh, M.; Vuong, X.; Okochi, K.D.; McCaffrey, R.; Olesiak, M.; et al. Improving CRISPR–Cas specificity with chemical modifications in single-guide RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 46, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doench, J.G.; Fusi, N.; Sullender, M.; Hegde, M.; Vaimberg, E.W.; Donovan, K.F.; Smith, I.; Tothova, Z.; Wilen, C.; Orchard, R.; et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosicki, M.; Tomberg, K.; Bradley, A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR–Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aussel, C.; Cathomen, T.; Fuster-García, C. The hidden risks of CRISPR/Cas: Structural variations and genome integrity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yang, D.; Xu, J.; Zhu, T.; Chen, Y.E.; Zhang, J. RS-1 enhances CRISPR/Cas9- and TALEN-mediated knock-in efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno, S.; Fernández-Ávila, M.J.; Cruz-García, A.; Cepeda-García, C.; Gómez-Cabello, D.; Huertas, P. Neddylation inhibits CtIP-mediated resection and regulates DNA double strand break repair pathway choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Dougan, S.K.; Truttmann, M.C.; Bilate, A.M.; Ingram, J.R.; Ploegh, H.L. Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weterings, E.; Gallegos, A.C.; Dominick, L.N.; Cooke, L.S.; Bartels, T.N.; Vagner, J.; Matsunaga, T.O.; Mahadevan, D. A novel small molecule inhibitor of the DNA repair protein Ku70/80. DNA Repair 2016, 43, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M.; Mok, G.; Heravi, M.; Lee, L.; Vuong, T.; Aloyz, R.; Panasci, L.; Muanza, T. Effects of dna-Dependent Protein Kinase Inhibition by NU7026 on dna Repair and Cell Survival in Irradiated Gastric Cancer Cell Line N87. Curr. Oncol. 2014, 21, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutschner, T.; Haemmerle, M.; Genovese, G.; Draetta, G.F.; Chin, L. Post-translational Regulation of Cas9 during G1 Enhances Homology-Directed Repair. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, N.; Ringnalda, F.C.; Lindsay, H.; Berk, C.; Bargsten, K.; Li, Y.; Neri, D.; Robinson, M.D.; Ciaudo, C.; Hall, J.; et al. Covalent linkage of the DNA repair template to the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease enhances homology-directed repair. eLife 2018, 7, e33761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Bashir, S.; Li, X.; Rossius, J.; Chu, V.T.; Rajewsky, K.; Kühn, R. Enhancement of Precise Gene Editing by the Association of Cas9 with Homologous Recombination Factors. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ruan, J.; Song, J.; Wen, L.; Yang, D.; Zhao, J.; Xia, X.; Chen, Y.E.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. MiCas9 increases large size gene knock-in rates and reduces undesirable on-target and off-target indel edits. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, C.T.; Deshpande, P.S.; Dever, D.P.; Camarena, J.; Lemgart, V.T.; Cromer, M.K.; Vakulskas, C.A.; Collingwood, M.A.; Zhang, L.; Bode, N.M.; et al. Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Ono, K. VERVE-101: A promising CRISPR-based gene editing therapy that reduces LDL-C and PCSK9 levels in HeFH patients. Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2023, 10, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flight, P.; Rohde, E.; Lee, R.; Mazzola, A.M.; Platt, C.; Mizoguchi, T.; Pendino, K.; Chadwick, A.; Khera, A.; Vafai, S.; et al. † VERVE-102, a clinical stage in vivo base editing medicine, leads to potent and precise inactivation of PCSK9 in preclinical studies. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Exploration Trial of YOLT-101 in the Treatment of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06461702 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Phase 1b Study of VERVE-201 in Patients with Refractory Hyperlipidemia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06451770 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Morrow, P.K.; Chen, Y.-S.; Serwer, L.; Detwiler, Z.; Flanagan, N.; Koch, E.; Zhang, M.L.; Mu, M.; Nguyen, T.; Sula, E.; et al. Abstract 16908: CTX310: An Investigational in vivo CRISPR-Based Therapy Efficiently and Durably Reduces ANGPTL3 Protein and Triglyceride Levels in Non-Human Primates After a Single Dose. Circulation 2023, 148, A16908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World’s First Gene-Editing Therapy Targeting APOC3 for Hyperlipidemia. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-worlds-first-gene-editing-therapy-targeting-apoc3-for-hyperlipidemia-302606367.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Hussain, A.; Ding, X.; Alariqi, M.; Manghwar, H.; Hui, F.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wu, C.; Cao, J.; Jin, S. Herbicide Resistance: Another Hot Agronomic Trait for Plant Genome Editing. Plants 2021, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Randolph, P.B.; Davis, J.R.; Sousa, A.A.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Chen, P.J.; Wilson, C.; Newby, G.A.; Raguram, A.; et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

| Platform (Reference) | Cargo Type | Cargo Size | Immunogenicity | Genome Integration | Tissue Tropism | Particle Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV [39] | DNA | ~4.7 kb | Low-moderate | Rare (episomal) | Broad, serotype-dependent | ~20–25 nm |

| AdV [40] | DNA | ~8–36 kb | High | No | Broad (liver, airway, etc.) | ~70–100 nm |

| LV [41] | RNA (retroviral) | ~8–10 kb | Moderate | Yes (integrates) | Broad, envelope-dependent | ~80–120 nm |

| VLP [42] | Protein or peptide | Variable (<150 kDa protein typical) | Low | No | Customizable by engineering | ~20–200 nm (system-dependent) |

| LNP [43] | DNA, mRNA, protein, or small molecules | Up to ~15 kb mRNA | Low-moderate | No | Liver primarily, or engineered targeting | ~60–150 nm |

| Gene | Key Mechanism Exploited in LivGETx-CVD | Hypothesized Loss of Function Effects in LivGETx-CVD |

|---|---|---|

| PCSK9 | Degrade LDLR | Retention of LDLR → reduced cholesterol in the blood → less CVD risks |

| ANGPTL3 | Inhibit LPL | Less inhibition of LPL → increased digestion of triglycerides → reduced triglyceride levels in the blood → less CVD risks |

| CETP | Convert HDL to LDL | Less conversion of HDL to LDL → increased HDL-C and decreased LDL-C levels in the blood → less CVD risks |

| ApoC3 | Inhibit LPL | Less inhibition of LPL → increased digestion of triglycerides → reduced triglyceride levels in the blood → less CVD risks |

| ASGR1 | Inhibition of ASGR1 promotes bile excretion | Upregulation of reverse cholesterol transport → increased cholesterol excretion through feces → reduced cholesterol levels → less CVD risks |

| LPA | Pro-inflammation | Less inflammation → less CVD risks |

| IDOL | Degrade LDLR | Retention of LDLR → reduced cholesterol → less CVD risks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.E. Gene Editing Therapies Targeting Lipid Metabolism for Cardiovascular Disease: Tools, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Progress. Cells 2026, 15, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020134

Ren Z, Zhou J, Yang D, Guo Y, Zhang J, Xu J, Chen YE. Gene Editing Therapies Targeting Lipid Metabolism for Cardiovascular Disease: Tools, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Progress. Cells. 2026; 15(2):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020134

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Zhuoying, Jun Zhou, Dongshan Yang, Yanhong Guo, Jifeng Zhang, Jie Xu, and Y Eugene Chen. 2026. "Gene Editing Therapies Targeting Lipid Metabolism for Cardiovascular Disease: Tools, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Progress" Cells 15, no. 2: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020134

APA StyleRen, Z., Zhou, J., Yang, D., Guo, Y., Zhang, J., Xu, J., & Chen, Y. E. (2026). Gene Editing Therapies Targeting Lipid Metabolism for Cardiovascular Disease: Tools, Delivery Strategies, and Clinical Progress. Cells, 15(2), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020134