Ovulation-Derived Fibronectin Promotes Peritoneal Seeding of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Precursor Cells via Integrin β1 Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Sources

2.2. Clinical Specimens

2.3. ELISA Assay

2.4. AIG

2.5. Anoikis Resistance Assay

2.6. 2D/3D Cell Migration and Invasion Assay

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. Xenograft Tumor Model

2.9. Statistics

3. Result

3.1. High Molecular Weight Components, Including FN, in FF Promote Migration of HGSC Precursor Cells

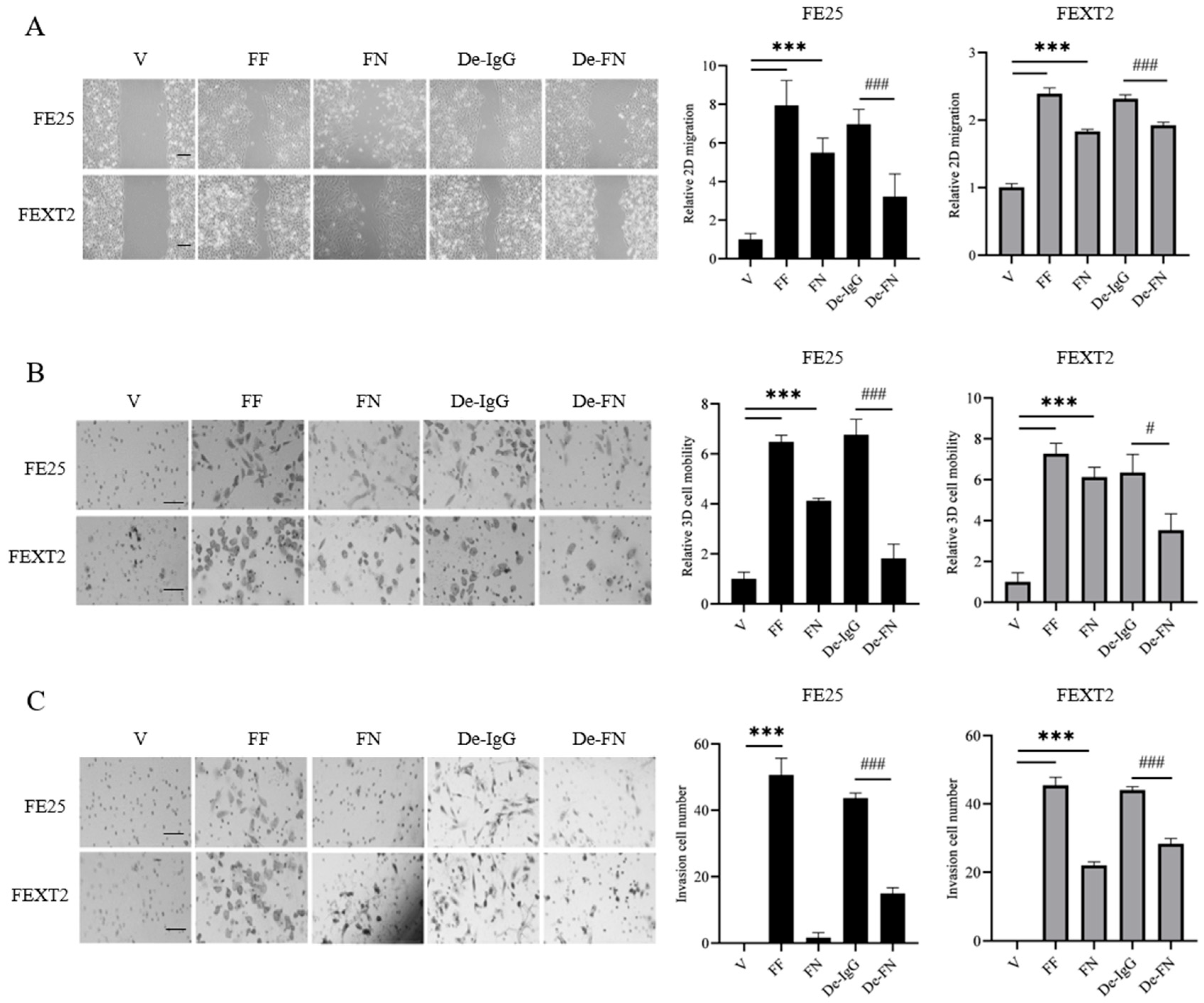

3.2. Depletion of FN from FF Partially Compromises Migration and Invasion

3.3. FF Enhances Proliferation Independently of FN

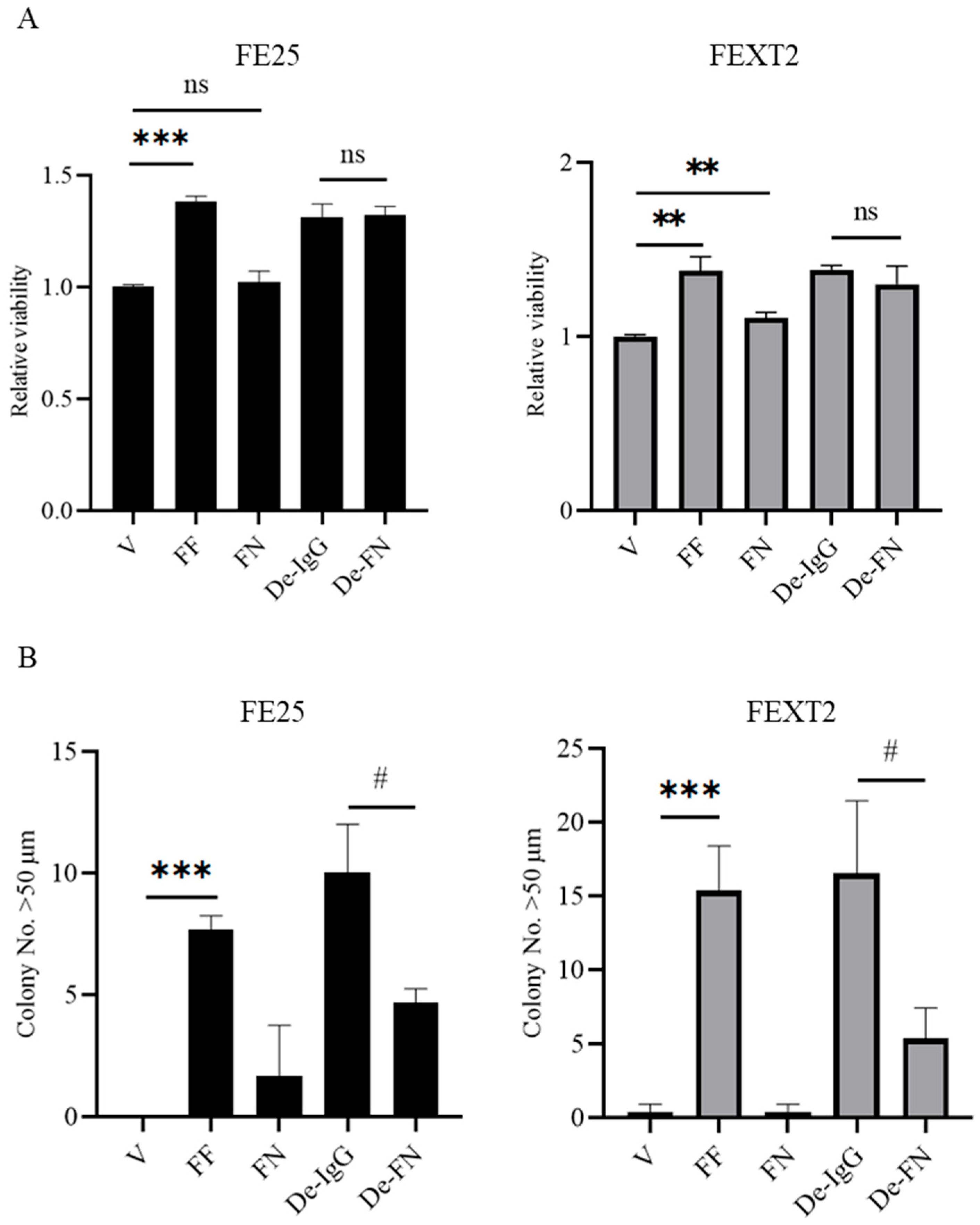

3.4. FN Plays a Minor Role in Anoikis Resistance and Anchorage-Independent Growth (AIG)

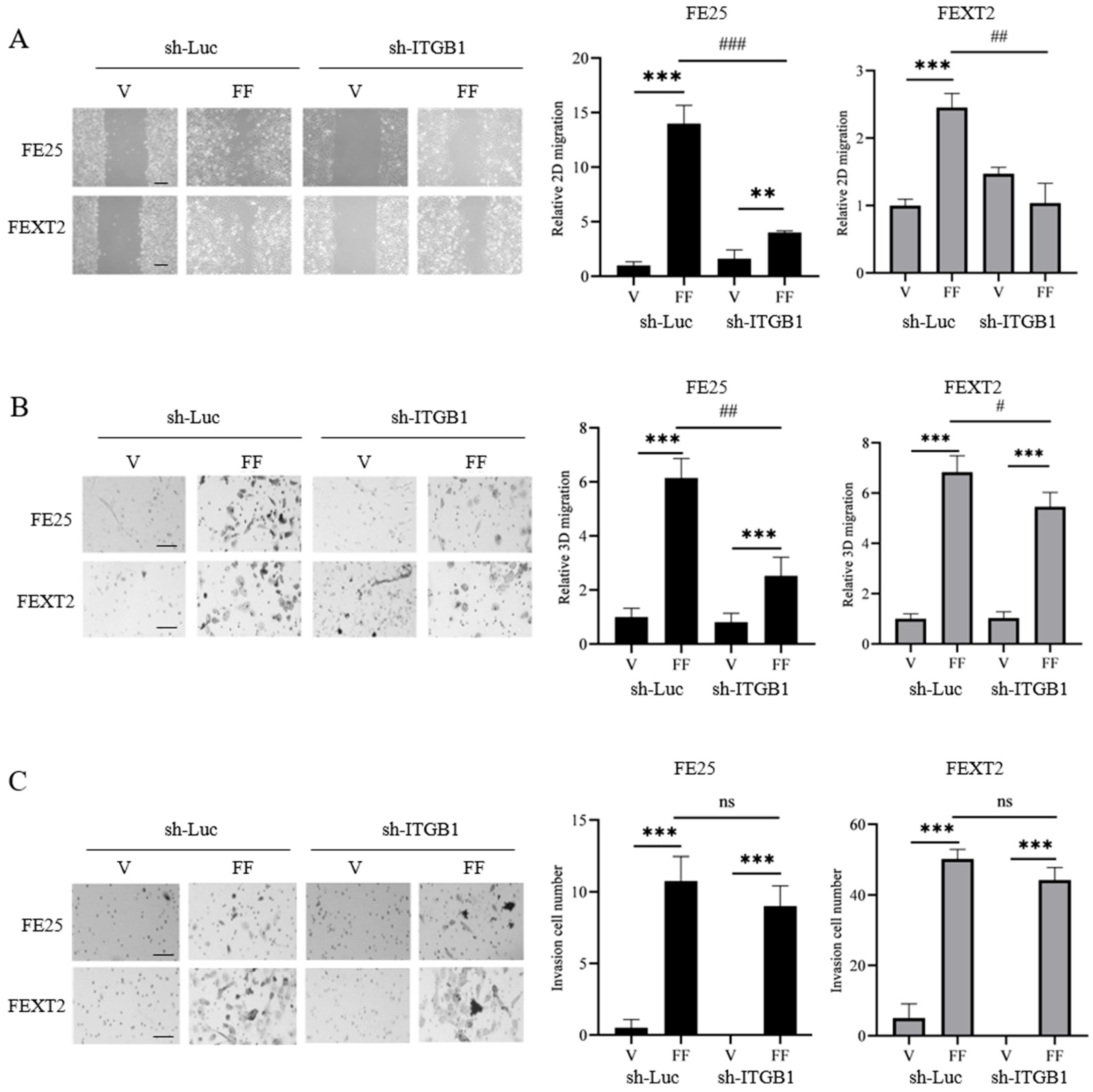

3.5. ITGB1 Knockdown Reduces FF-Induced Migration but Not Invasion

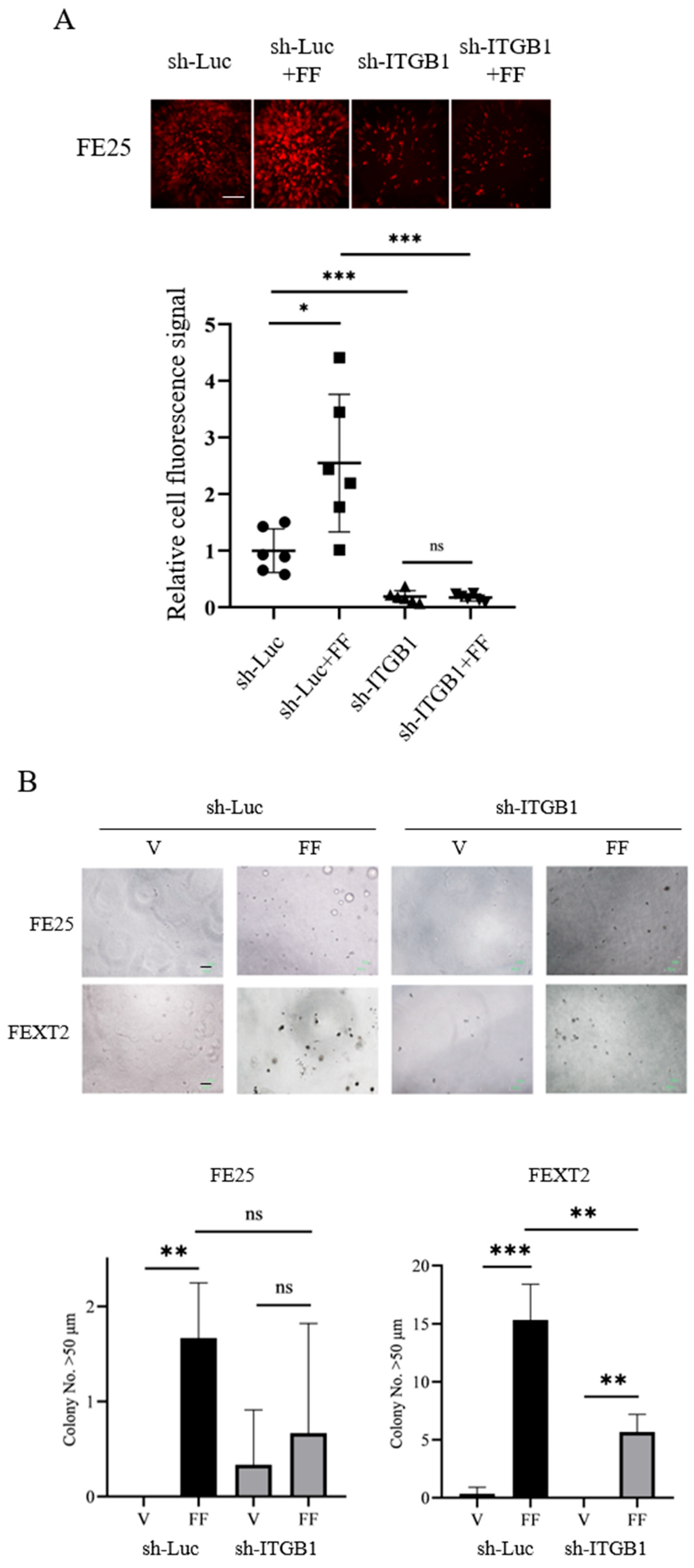

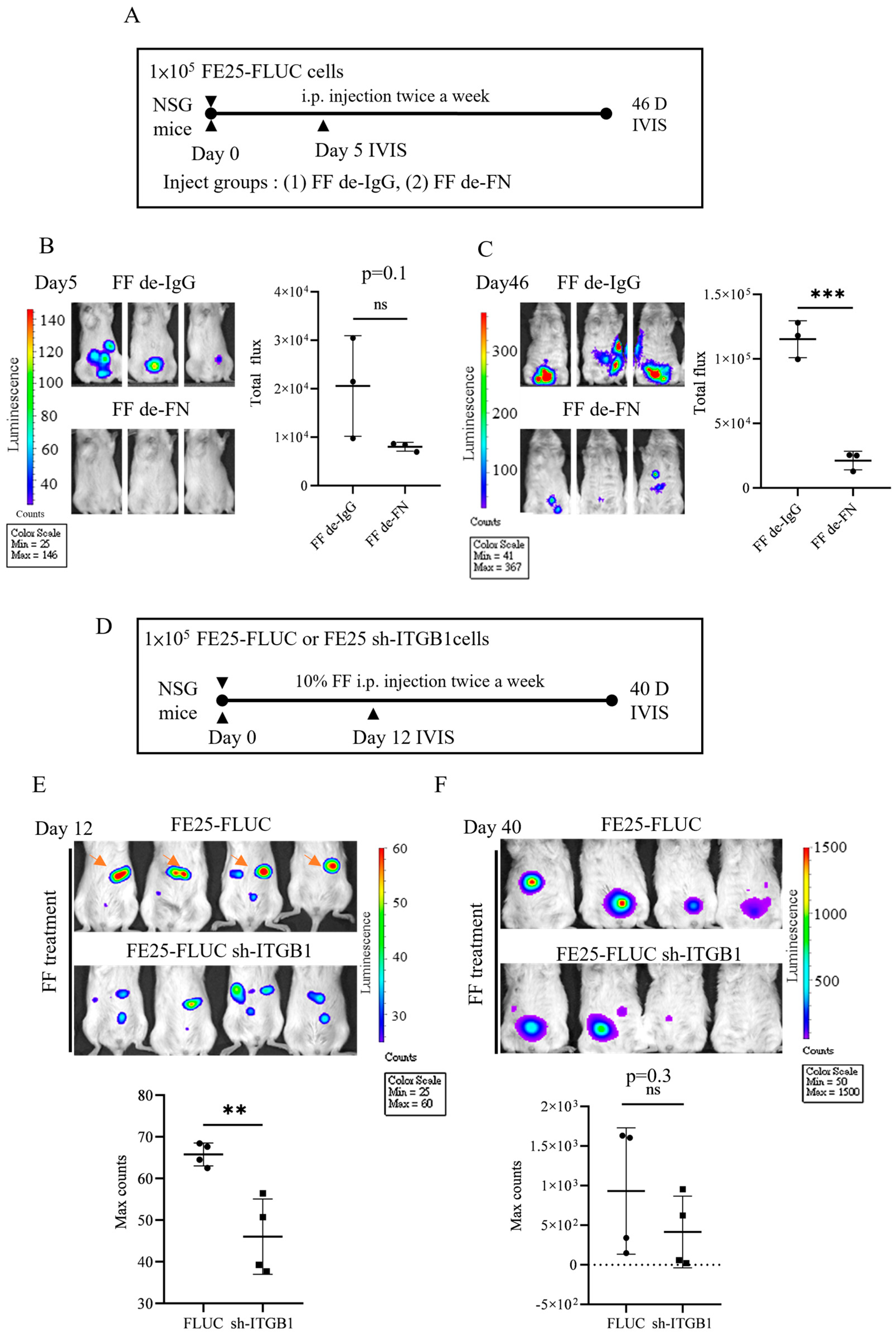

3.6. ITGB1 Knockdown Compromises Peritoneal Attachment and AIG

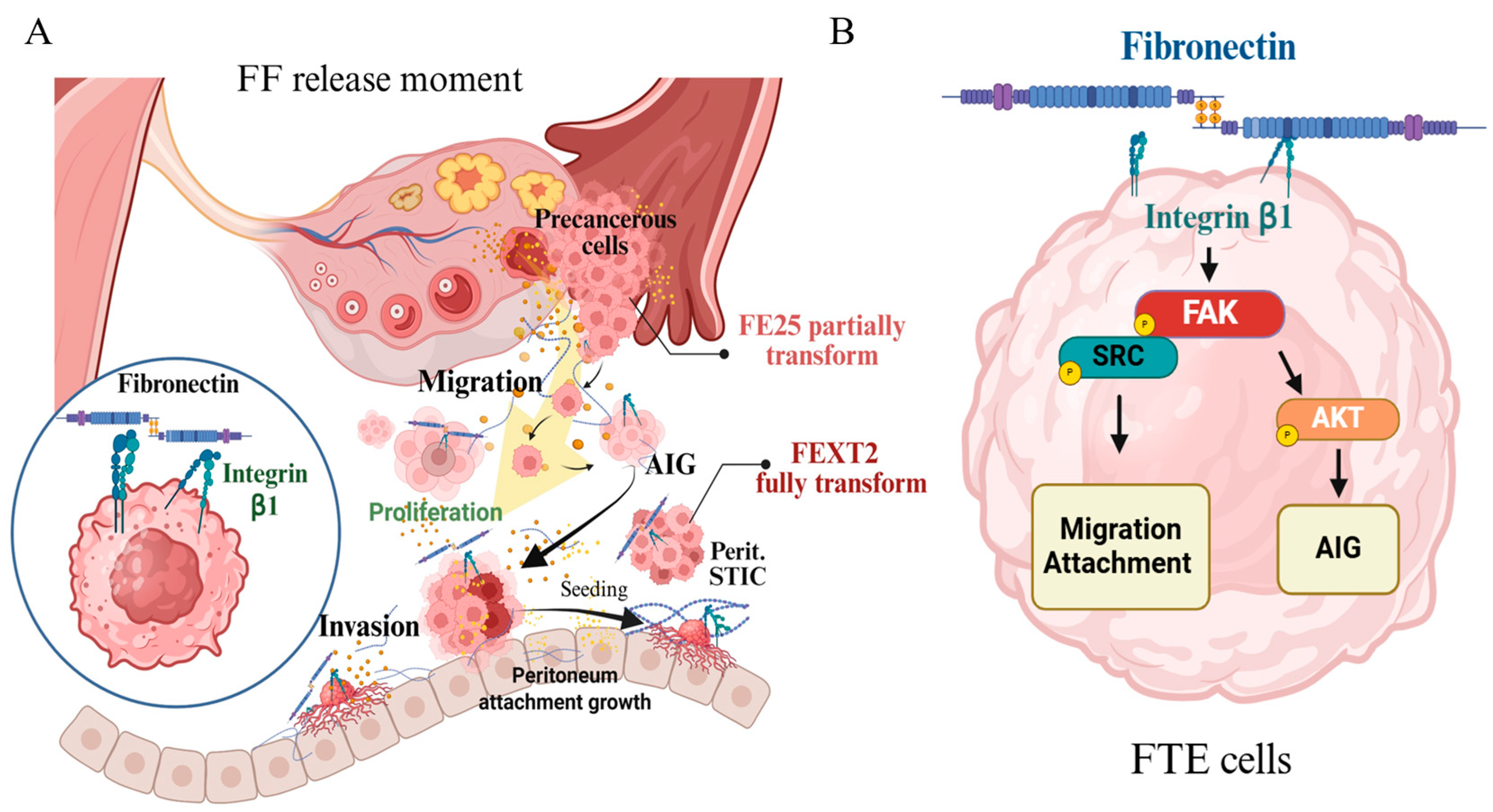

3.7. Pro-Metastasis Effect of the FF-FN/ITGB1 Signaling

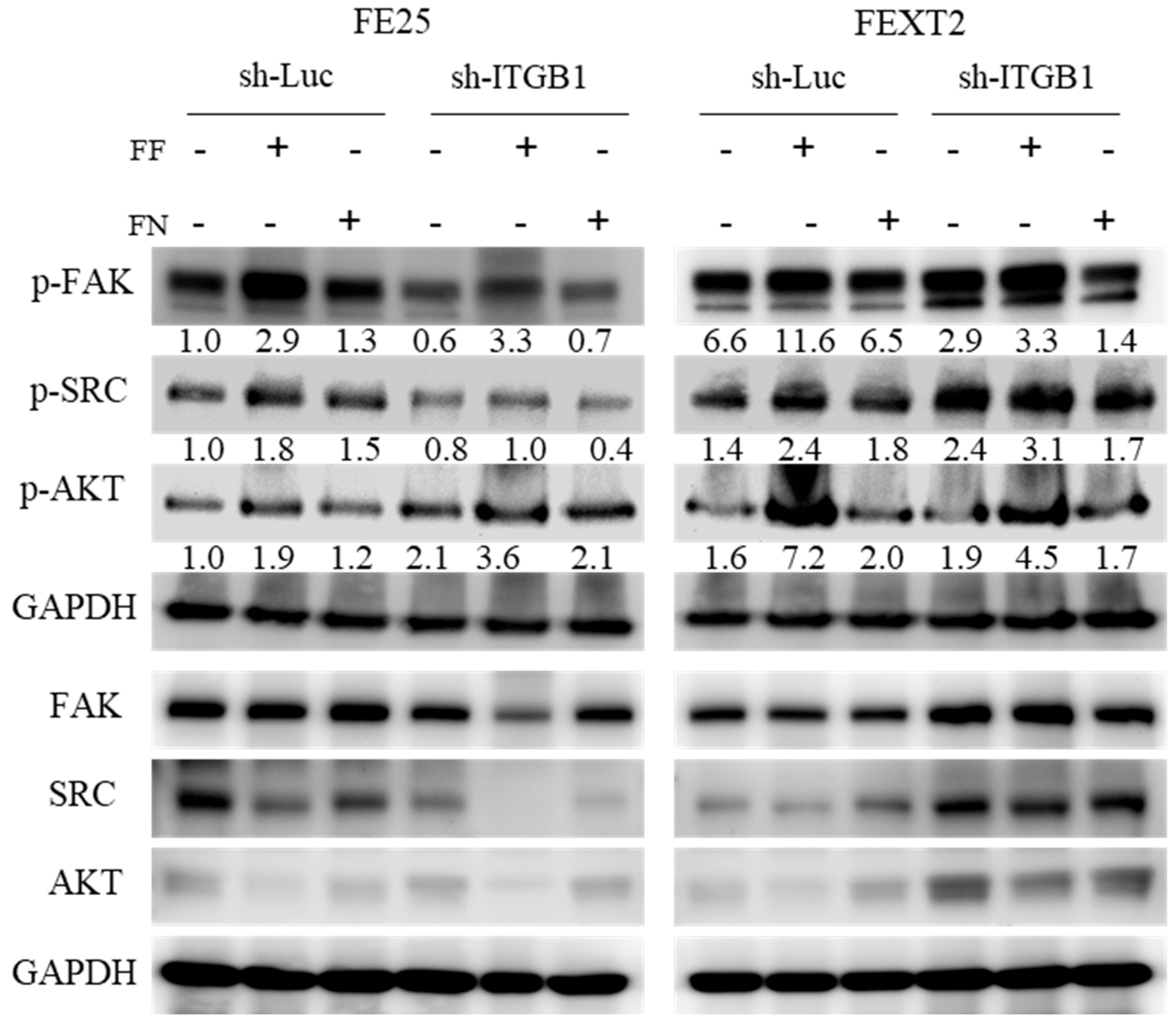

3.8. FF-FN Activities Were Partially Mediated by ITGB1-FAK/SRC/AKT Pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. FF-Derived FN as a Key Mediator of Early Metastasis

4.2. Role of ITGB1 Signaling in Promoting FTE Cell Migration and Tumor Progression

4.3. Fully Transformed FTE Cells Are Less Dependent on FF Signals for Migration and Invasion

4.4. Signals Downstream of FF-FN/ITGB1

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HGSC | High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma |

| FTE | Fallopian tube epithelial |

| FN | Fibronectin |

| ITGB1 | Integrin β1 |

| HGSC | High-grade serous carcinoma |

| ROS | Oxygen species |

| FF | Follicular fluid |

| IGF2 | Insulin-like growth factor 2 |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| PF | Peritoneal fluid |

| AIG | Anchorage-independent growth |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneally |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| NSG | NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγnull |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P.M.; Jordan, S.J. Global epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovac, D.; Armstrong, D.K. Recent progress in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, B.; Edwards, R.P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 32, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, R.J.; Shih Ie, M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: A proposed unifying theory. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, I.M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.L. The Origin of Ovarian Cancer Species and Precancerous Landscape. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, R.J. Origin and molecular pathogenesis of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24 (Suppl. 10), x16–x21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Papp, E.; Hallberg, D.; Niknafs, N.; Adleff, V.; Noe, M.; Bhattacharya, R.; Novak, M.; Jones, S.; Phallen, J.; et al. High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, E.Y.; Kim, O.; Schilder, J.M.; Coffey, D.M.; Cho, C.H.; Bast, R.C., Jr. Cell Origins of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, T.R.; Kolin, D.L.; Teschan, N.J.; Crum, C.P. Back to the Future? The Fallopian Tube, Precursor Escape and a Dualistic Model of High-Grade Serous Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2018, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, T.R.; Howitt, B.E.; Horowitz, N.; Nucci, M.R.; Crum, C.P. The fallopian tube, “precursor escape” and narrowing the knowledge gap to the origins of high-grade serous carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 152, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijron, J.G.; Seldenrijk, C.A.; Zweemer, R.P.; Lange, J.G.; Verheijen, R.H.; van Diest, P.J. Fallopian tube intraluminal tumor spread from noninvasive precursor lesions: A novel metastatic route in early pelvic carcinogenesis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, T.R.; Howitt, B.E.; Miron, A.; Horowitz, N.S.; Campbell, F.; Feltmate, C.M.; Muto, M.G.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Nucci, M.R.; Xian, W.; et al. Evidence for lineage continuity between early serous proliferations (ESPs) in the Fallopian tube and disseminated high-grade serous carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2018, 246, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Chen, P.C.; Seenan, V.; Ding, D.C.; Chu, T.Y. Ovulatory Follicular Fluid Facilitates the Full Transformation Process for the Development of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Seenan, V.; Wang, L.Y.; Chen, P.C.; Ding, D.C.; Chu, T.Y. Human peritoneal fluid exerts ovulation- and nonovulation-sourced oncogenic activities on transforming fallopian tube epithelial cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Huang, H.S.; Chen, P.C.; Ding, D.C.; Chu, T.Y. IGF-axis confers transformation and regeneration of fallopian tube fimbria epithelium upon ovulation. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.S.; Chen, P.C.; Chu, S.C.; Lee, M.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Chu, T.Y. Ovulation sources coagulation protease cascade and hepatocyte growth factor to support physiological growth and malignant transformation. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khine, A.A.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Chu, S.C.; Huang, H.S.; Chu, T.Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor ligands enriched in follicular fluid exosomes promote oncogenesis of fallopian tube epithelial cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.F.; Seenan, V.; Wang, L.Y.; Chu, T.Y. Ovulation Enhances Intraperitoneal and Ovarian Seedings of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cells Originating from the Fallopian Tube: Confirmation in a Bursa-Free Mouse Xenograft Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamah, A.M.; Hassis, M.E.; Albertolle, M.E.; Williams, K.E. Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid from fertile women. Clin. Proteom. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, C.J.; Lemmon, C.A. Fibronectin: Molecular Structure, Fibrillar Structure and Mechanochemical Signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Mo, J.; Dong, S.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, P. Integrinbeta-1 in disorders and cancers: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Yang, C.H.; Cheng, L.H.; Chang, W.T.; Lin, Y.R.; Cheng, H.C. Fibronectin in Cancer: Friend or Foe. Cells 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P.; Hielscher, A. Fibronectin: How Its Aberrant Expression in Tumors May Improve Therapeutic Targeting. J. Cancer 2017, 8, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranga, V.; Dakal, T.C.; Maurya, P.K.; Johnson, M.S.; Sharma, N.K.; Kumar, A. Role of RGD-binding Integrins in ovarian cancer progression, metastasis and response to therapy. Integr. Biol. 2025, 17, zyaf003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Ono, Y.J.; Kanemura, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hayashi, M.; Terai, Y.; Ohmichi, M. Hepatocyte growth factor secreted by ovarian cancer cells stimulates peritoneal implantation via the mesothelial-mesenchymal transition of the peritoneum. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Yang, Z.; Heyrman, G.M.; Cain, B.P.; Lopez Carrero, A.; Isenberg, B.C.; Dean, M.J.; Coppeta, J.; Burdette, J.E. Versican secreted by the ovary links ovulation and migration in fallopian tube derived serous cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022, 543, 215779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, A.; Li, W.; Dipali, S.S.; Cologna, S.M.; Pavone, M.E.; Duncan, F.E.; Burdette, J.E. Follicular fluid aids cell adhesion, spreading in an age independent manner and shows an age-dependent effect on DNA damage in fallopian tube epithelial cells. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Tozer, A.J.; Butler, S.A.; Bell, C.M.; Docherty, S.M.; Iles, R.K. Follicular fluid levels of inhibin A, inhibin B, and activin A levels reflect changes in follicle size but are not independent markers of the oocyte’s ability to fertilize. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wetering, S.; van den Berk, N.; van Buul, J.D.; Mul, F.P.; Lommerse, I.; Mous, R.; ten Klooster, J.P.; Zwaginga, J.J.; Hordijk, P.L. VCAM-1-mediated Rac signaling controls endothelial cell-cell contacts and leukocyte transmigration. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2003, 285, C343–C352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Yan, D.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Cui, H. The Roles of Integrin alpha5beta1 in Human Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 13329–13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Iacob, R.E.; Li, J.; Engen, J.R.; Springer, T.A. Dynamics of integrin alpha5beta1, fibronectin, and their complex reveal sites of interaction and conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowter, H.M.; Corps, A.N.; Smith, S.K. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in ovarian epithelial tumour fluids stimulates the migration of ovarian carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 83, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.K.; Sawada, K.; Tiwari, P.; Mui, K.; Gwin, K.; Lengyel, E. Ligand-independent activation of c-Met by fibronectin and alpha(5)beta(1)-integrin regulates ovarian cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assoian, R.K.; Schwartz, M.A. Coordinate signaling by integrins and receptor tyrosine kinases in the regulation of G1 phase cell-cycle progression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001, 11, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soung, Y.H.; Clifford, J.L.; Chung, J. Crosstalk between integrin and receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in breast carcinoma progression. BMB Rep. 2010, 43, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Guo, S.; Xie, Y.; Yao, Y. The characteristics and the multiple functions of integrin beta1 in human cancers. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.; Giancotti, F.G. Integrin Signaling in Cancer: Mechanotransduction, Stemness, Epithelial Plasticity, and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, H.C. Crosstalk between hepatocyte growth factor and integrin signaling pathways. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 13, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislovas, J.; Kermorgant, S. c-Met-integrin cooperation: Mechanisms, tumorigenic effects, and therapeutic relevance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 994528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A.; Nguyen, A.; Chandra, A.; Sidorov, M.K.; Yagnik, G.; Rick, J.; Han, S.W.; Chen, W.; Flanigan, P.M.; Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; et al. Cross-activating c-Met/beta1 integrin complex drives metastasis and invasive resistance in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8685–E8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, D.; Wadhwa, H.; Sudhir, S.; Chang, A.C.; Jain, S.; Chandra, A.; Nguyen, A.T.; Spatz, J.M.; Pappu, A.; Shah, S.S.; et al. Role of c-Met/beta1 integrin complex in the metastatic cascade in breast cancer. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e138928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Basal Level (Vehicle) | FF | FN | De-IgG | De-FN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | |||||

| FE25 | 1.58 | 1.58× | 1.08× | 3.48 | 0.9× |

| FEXT2 | 1.95 | 1.43× | 1.1× | 2.37 | 0.9× |

| Anchorage independent growth (>50 μm) | |||||

| FE25 | 0 | 8 (No.) | 1.2 (No.) | 9.0 | 0.6 |

| FEXT2 | 0.3 | 16.3 (No.) | 0.3 (No.) | 14.9 | 0.4 |

| Anoikis resistance (OD) | |||||

| FE25 | 0.33 | 1.4× | 1.0× | 0.45 | 1.0× |

| FEXT2 | 0.39 | 1.4× | 1.1× | 0.53 | 0.9× |

| Peritoneal attachment growth (ROI) | |||||

| FE25 | N/A | 1.4× | N/A | 1 | 0.8× |

| FEXT2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2D Migration (Wound healing; µm2) | |||||

| FE25 | 4.62 × 104 | 8.8× | 5.5× | 3.36 × 105 | 0.5× |

| FEXT2 | 2.3 × 105 | 2.4× | 2.2× | 5.36 × 105 | 0.6× |

| 3D Migration (Transwell assay; cell number) | |||||

| FE25 | 5.75 | 6.1× | 4× | 38 | 0.3× |

| FEXT2 | 4.75 | 6.8× | 6× | 29.6 | 0.6× |

| Matrigel invasion (Cell number) | |||||

| FE25 | 0 | 54 (No.) | 1.7 (No.) | 44.3 | 0.3× |

| FEXT2 | 0 | 47 (No.) | 21 (No.) | 45.3 | 0.6× |

| Cell Line | FE25 sh-Luc | FE25 sh-ITGB1 | FEXT2 sh-Luc | FEXT2 sh-ITGB1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal level (Vehicle) | FF | Basal level (Vehicle) | FF | Basal level (Vehicle) | FF | Basal level (Vehicle) | FF | |

| Proliferation | 0.27 | 1.57× | 0.68 | 1.18× | 0.86 | 1.91× | 1.23 | 0.99× |

| Anchorage independent growth (>50 μm, No.) | 0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 15.3 | 0 | 5.7 |

| Anoikis resistance (OD) | 0.20 | 1.4× | 0.20 | 1.4× | 0.20 | 1.4× | 0.25 | 2.0× |

| Peritoneal attachment growth (ROI) | 1.16 × 105 | 2.5× | 2.2 × 104 | 0.17× | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2D Migration (Wound healing, µm2) | 1.83 × 104 | 14.0× | 2.01 × 104 | 4× | 1.34 × 105 | 2.4× | 1.82 × 105 | 0.9× |

| 3D Migration (Transwell assay, No.) | 5.25 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 8.75 | 6.8 | 1 | 5.5 |

| Matrigel invasion (No.) | 0.5 | 10 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 50 | 0 | 44.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hsu, C.-F.; Wang, L.-Y.; Seenan, V.; Chen, P.-C.; Chu, T.-Y. Ovulation-Derived Fibronectin Promotes Peritoneal Seeding of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Precursor Cells via Integrin β1 Signaling. Cells 2026, 15, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010080

Hsu C-F, Wang L-Y, Seenan V, Chen P-C, Chu T-Y. Ovulation-Derived Fibronectin Promotes Peritoneal Seeding of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Precursor Cells via Integrin β1 Signaling. Cells. 2026; 15(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Che-Fang, Liang-Yuan Wang, Vaishnavi Seenan, Pao-Chu Chen, and Tang-Yuan Chu. 2026. "Ovulation-Derived Fibronectin Promotes Peritoneal Seeding of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Precursor Cells via Integrin β1 Signaling" Cells 15, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010080

APA StyleHsu, C.-F., Wang, L.-Y., Seenan, V., Chen, P.-C., & Chu, T.-Y. (2026). Ovulation-Derived Fibronectin Promotes Peritoneal Seeding of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Precursor Cells via Integrin β1 Signaling. Cells, 15(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010080