Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery of a Selective TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitor with Topical Anti-Allergic Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of a Virtual Pentapeptide Database

Molecular Docking

2.2. Peptide Synthesis and Purification

2.3. Cell Culture and Transient Transfection

2.4. Electrophysiology

2.5. Human Skin Patch Test

2.6. Statistics and Reproducibility

3. Results

3.1. Virtual Screening of rTRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitors

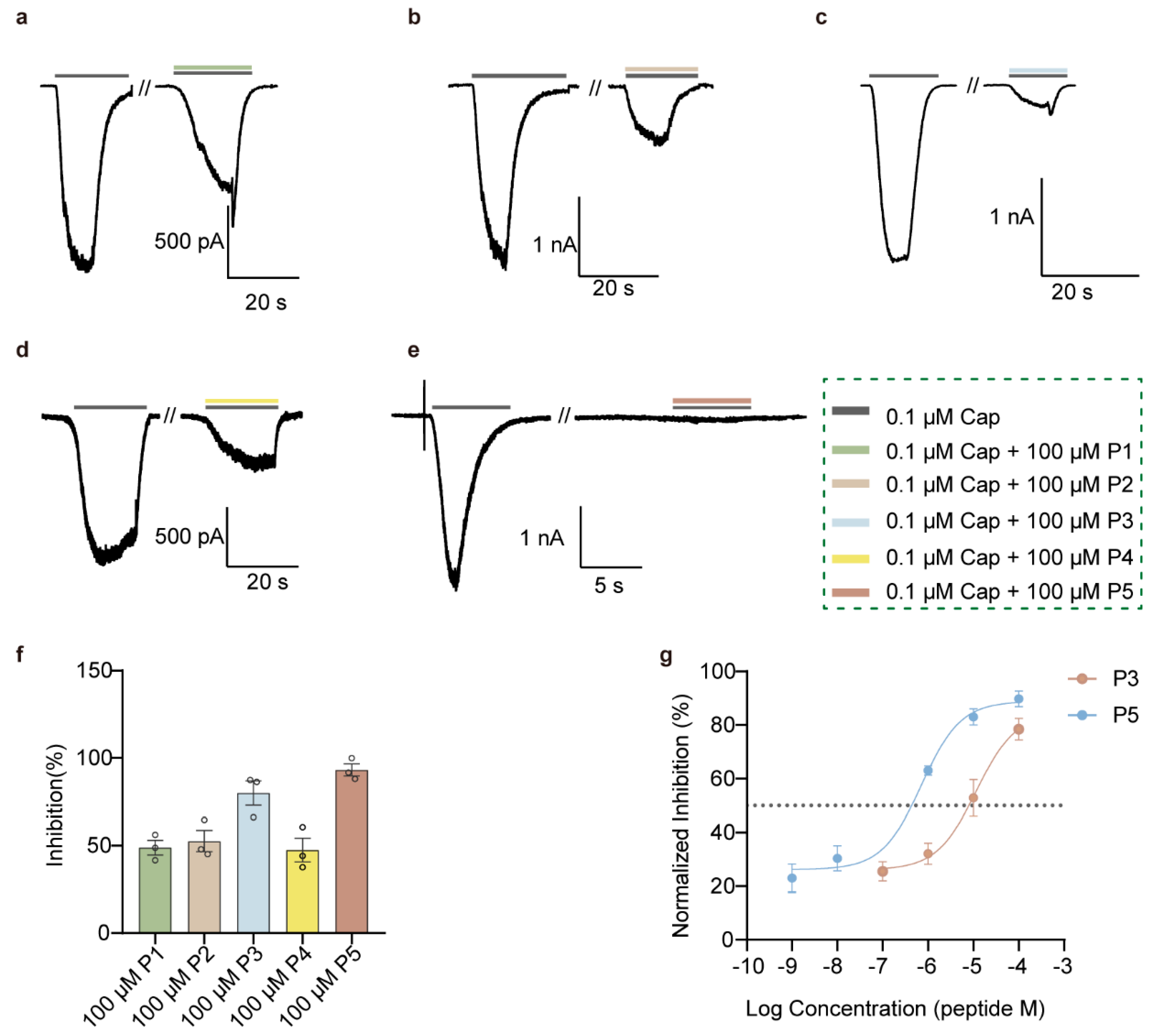

3.2. P3 and P5 Significantly Inhibit rTRPV1

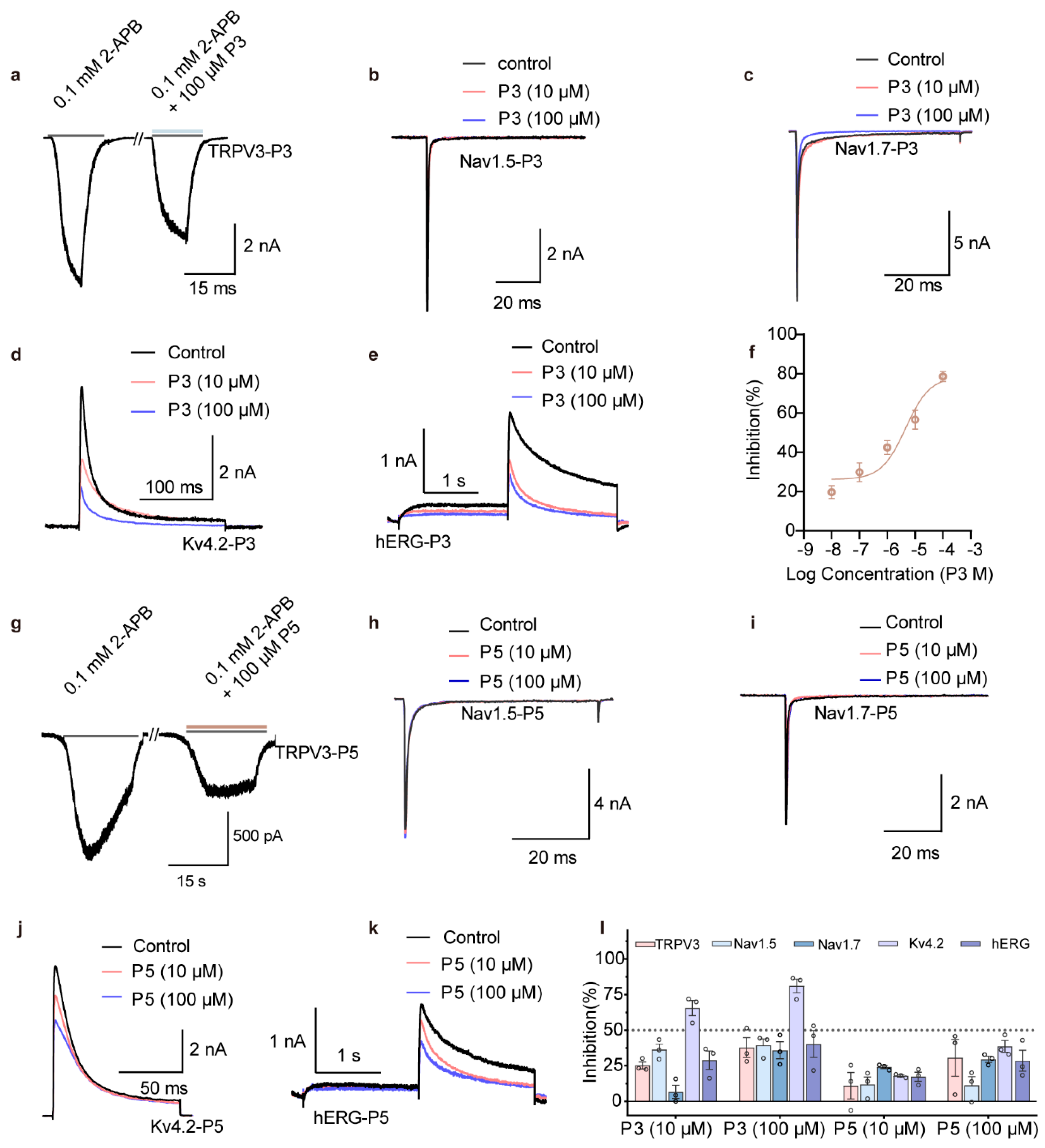

3.3. High-Selectivity rTRPV1 Inhibitor P5

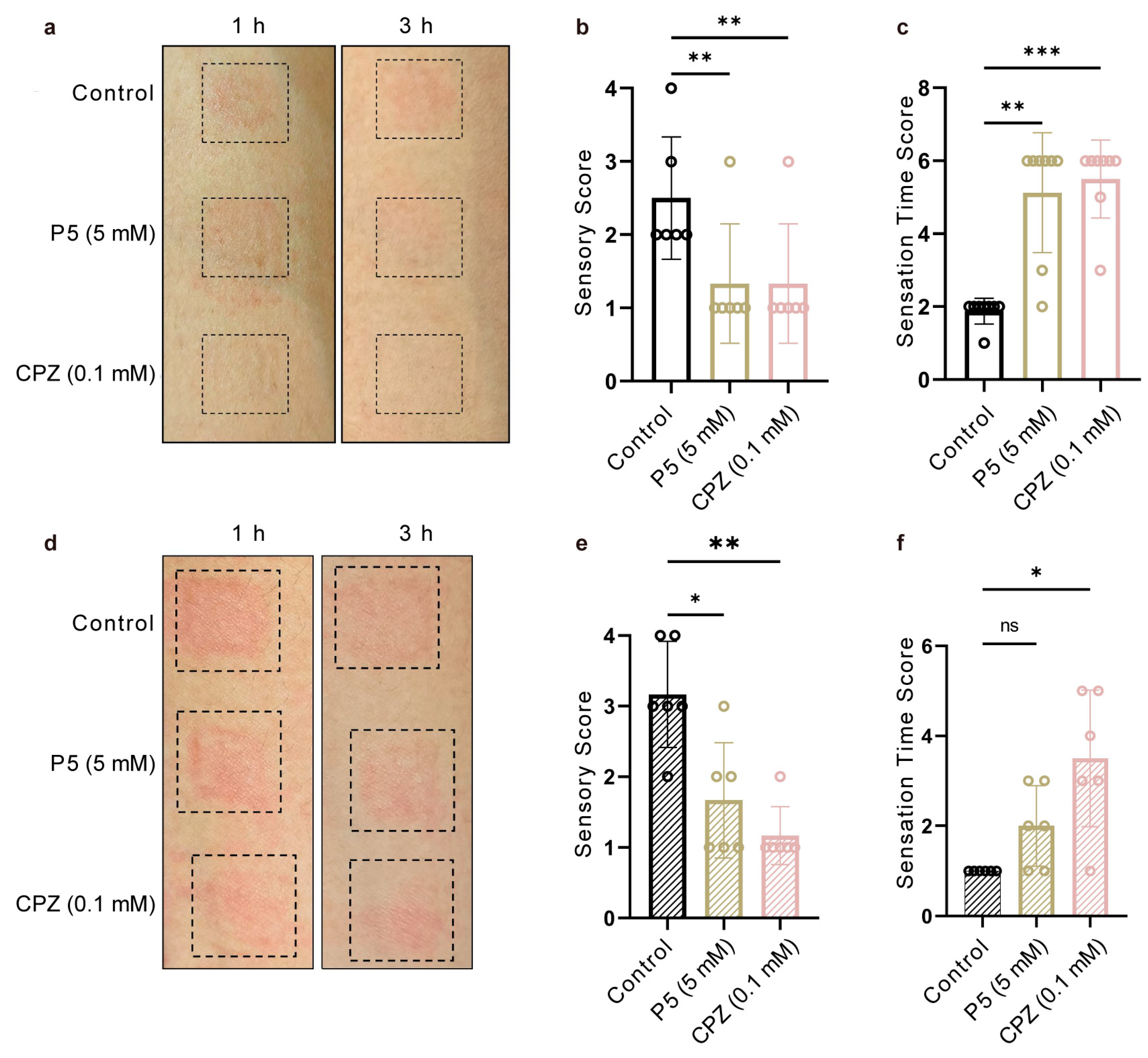

3.4. P5 Alleviated Capsaicin-Induced Skin Hypersensitivity in Human Skin

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenberger, D.C.; Binzen, U.; Treede, R.D.; Greffrath, W. The capsaicin receptor TRPV1 is the first line defense protecting from acute non damaging heat: A translational approach. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caterina, M.J.; Pang, Z. TRP Channels in Skin Biology and Pathophysiology. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Iida, T.; Mizuno, A.; Suzuki, M.; Caterina, M.J. Altered thermal selection behavior in mice lacking transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Sun, M.; Zhao, C.; Kang, J. TRPV1: A promising therapeutic target for skin aging and inflammatory skin diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1037925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagood, M.D.; Isseroff, R.R. TRPV1: Role in Skin and Skin Diseases and Potential Target for Improving Wound Healing. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yang, P.; Mack, M.R.; Dryn, D.; Luo, J.; Gong, X.; Liu, S.; Oetjen, L.K.; Zholos, A.V.; Mei, Z.; et al. Sensory TRP channels contribute differentially to skin inflammation and persistent itch. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Lebovitz, E.E.; Keller, J.M.; Mannes, A.J.; Nemenov, M.I.; Iadarola, M.J. Nociception and inflammatory hyperalgesia evaluated in rodents using infrared laser stimulation after Trpv1 gene knockout or resiniferatoxin lesion. Pain 2014, 155, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walder, R.Y.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Loo, L.; Rasmussen, L.A.; Mohapatra, D.P.; Wilson, S.P.; Sluka, K.A. TRPV1 is important for mechanical and heat sensitivity in uninjured animals and development of heat hypersensitivity after muscle inflammation. Pain 2012, 153, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Deng, S.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Y. TRPV1: The key bridge in neuroimmune interactions. J. Intensive Med. 2024, 4, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, C.; Zanfirescu, A.; Nițulescu, G.M.; Olaru, O.T.; Negreș, S. Natural Active Ingredients and TRPV1 Modulation: Focus on Key Chemical Moieties Involved in Ligand-Target Interaction. Plants 2023, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, O.; Soares, G.B.; Yosipovitch, G. Transient Receptor Potential Channels and Itch. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Won, C.H.; Jung, K.; Nam, H.J.; Choi, G.; Park, Y.H.; Park, M.; Kim, B. Efficacy and safety of PAC-14028 cream—A novel, topical, nonsteroidal, selective TRPV1 antagonist in patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: A phase IIb randomized trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 180, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Won, C.; Park, C.O.; Chung, B.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Jung, K.; Nam, H.J.; Choi, G.; et al. Asivatrep, a TRPV1 antagonist, for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis: Phase 3, randomized, vehicle-controlled study (CAPTAIN-AD). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1340–1347.e1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R.A.; Robertson, J.; Mistry, H.; McCallum, S.; Fernando, D.; Wyres, M.; Yosipovitch, G. A randomised trial evaluating the effects of the TRPV1 antagonist SB705498 on pruritus induced by histamine, and cowhage challenge in healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunthorpe, M.J.; Hannan, S.L.; Smart, D.; Jerman, J.C.; Arpino, S.; Smith, G.D.; Brough, S.; Wright, J.; Egerton, J.; Lappin, S.C.; et al. Characterization of SB-705498, a potent and selective vanilloid receptor-1 (VR1/TRPV1) antagonist that inhibits the capsaicin-, acid-, and heat-mediated activation of the receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 321, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, E.H.B.; Assis, L.C.; de Oliveira, T.A.; da Silva, A.M.; Taranto, A.G. Structure-Based Virtual Screening: From Classical to Artificial Intelligence. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.T. Making virtual screening a reality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6902–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, F.; Junaid, M.; Almalki, A.H.; Almaghrabi, M.; Ghazanfar, S.; Tahir Ul Qamar, M. Deep learning pipeline for accelerating virtual screening in drug discovery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggia, M.; Natale, B.; Amendola, G.; Di Maro, S.; Cosconati, S. Streamlining Large Chemical Library Docking with Artificial Intelligence: The PyRMD2Dock Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 2143–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P. Structural biology of thermoTRPV channels. Cell Calcium 2019, 84, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Cao, E.; Julius, D.; Cheng, Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature 2013, 504, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, E.; Julius, D.; Cheng, Y. TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature 2016, 534, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, R.M. Update on ICH E14/S7B Cardiac Safety Regulations: The Expanded Role of Preclinical Assays and the “Double-Negative” Scenario. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2021, 10, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colatsky, T.; Fermini, B.; Gintant, G.; Pierson, J.B.; Sager, P.; Sekino, Y.; Strauss, D.G.; Stockbridge, N. The Comprehensive in Vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) initiative—Update on progress. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2016, 81, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.I.; Oláh, A.; Szöllősi, A.G.; Bíró, T. TRP channels in the skin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2568–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Li, R.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, X. High-Affinity Peptides for Target Protein Screened in Ultralarge Virtual Libraries. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 2111–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, M.; Mercurio, F.A.; Leone, M. Virtual Screening of Peptide Libraries: The Search for Peptide-Based Therapeutics Using Computational Tools. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffler, A.E.; Kuryatov, A.; Zebroski, H.A.; Powell, S.R.; Filipenko, P.; Hussein, A.K.; Gorson, J.; Heizmann, A.; Lyskov, S.; Tsien, R.W.; et al. Discovery of peptide ligands through docking and virtual screening at nicotinic acetylcholine receptor homology models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8100–E8109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumroy, R.A.; De Jesús-Pérez, J.J.; Protopopova, A.D.; Rocereta, J.A.; Fluck, E.C.; Fricke, T.; Lee, B.H.; Rohacs, T.; Leffler, A.; Moiseenkova-Bell, V. Molecular details of ruthenium red pore block in TRPV channels. EMBO Rep. 2024, 25, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, A.; Nadezhdin, K.D.; Sobolevsky, A.I. Structural mechanisms of TRPV6 inhibition by ruthenium red and econazole. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; Chuang, A.Y.; Cohen, B.E.; Chuang, H.H. Activity-dependent targeting of TRPV1 with a pore-permeating capsaicin analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8497–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.; Sheth, S.; Mukherjea, D.; Rybak, L.P.; Ramkumar, V. TRPV1: A Potential Drug Target for Treating Various Diseases. Cells 2014, 3, 517–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucana, M.C.; Arruga, Y.; Petrachi, E.; Roig, A.; Lucchi, R.; Oller-Salvia, B. Protease-Resistant Peptides for Targeting and Intracellular Delivery of Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, D.; Prakash, S.; Anand, P.; Kaur, H.; Agrawal, P.; Mehta, A.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S.; Raghava, G.P. PEPlife: A Repository of the Half-life of Peptides. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttger, R.; Hoffmann, R.; Knappe, D. Differential stability of therapeutic peptides with different proteolytic cleavage sites in blood, plasma and serum. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Musaimi, O.; Lombardi, L.; Williams, D.R.; Albericio, F. Strategies for Improving Peptide Stability and Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.B.; Smith, E.W. The role of percutaneous penetration enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 18, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagen, S.K. Topical Peptide Treatments with Effective Anti-Aging Results. Cosmetics 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimogaki, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Tamai, H.; Masuda, M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of ellagic acid on melanogenesis inhibition. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2000, 22, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, M.J.; Schumacher, M.A.; Tominaga, M.; Rosen, T.A.; Levine, J.D.; Julius, D. The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997, 389, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hou, W.; Rong, M. Raw dataset of the pentapeptide library-Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery and Activity Evaluation of TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitors. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hou, W.; Rong, M. Code-Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery and Activity Evaluation of TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitors. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Hou, W.; He, Q.; Yuan, F.; Guo, C.; Liu, R.; Huang, B.; Wubulikasimu, A.; Rong, M. Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery of a Selective TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitor with Topical Anti-Allergic Efficacy. Cells 2026, 15, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010079

Liu L, Hou W, He Q, Yuan F, Guo C, Liu R, Huang B, Wubulikasimu A, Rong M. Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery of a Selective TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitor with Topical Anti-Allergic Efficacy. Cells. 2026; 15(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lulu, Wenqian Hou, Qinyi He, Fuchu Yuan, Changrun Guo, Ruxia Liu, Biao Huang, Atikan Wubulikasimu, and Mingqiang Rong. 2026. "Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery of a Selective TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitor with Topical Anti-Allergic Efficacy" Cells 15, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010079

APA StyleLiu, L., Hou, W., He, Q., Yuan, F., Guo, C., Liu, R., Huang, B., Wubulikasimu, A., & Rong, M. (2026). Virtual Screening–Guided Discovery of a Selective TRPV1 Pentapeptide Inhibitor with Topical Anti-Allergic Efficacy. Cells, 15(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010079