Multiomic Analyses Reveal Brainstem Metabolic Changes in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome

Highlights

- There are widespread metabolic changes in the brainstem of Scn1aA1783V/WT HET mice.

- Metabolomic analyses reveal age-specific (brainstem versus forebrain) alterations in HETs.

- Several druggable protein kinases are altered in the brainstem of HET mice.

- The findings of this study suggest a role of metabolic alterations in the brainstem as a plausible contributor to SUDEP pathogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Untargeted Metabolomic Analysis

- ➢

- Analysis of mass spectrometry data: Data were collected using MassHunter software version 12.0 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Metabolites were identified, and their peak area was recorded using MassHunter Quant. This data was transferred to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Metabolite identity was established using a combination of an in-house metabolite library developed using pure purchased standards, the NIST library, and the Fiehn library. Data were then analyzed using the “MetaboAnalyst” software tool (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). The steps involved uploading "raw input" followed by normalization and % CV analysis, which helped remove “failing compounds” by testing for individual metabolite reliability. Briefly, all the integration values were normalized relative to a labeled internal standard. This is carried out to account for minor errors caused by extraction or injection differences. Quality control (QC) samples are created by combining an equal amount of all samples in the experiment. The QC sample is injected at regular intervals between samples. During the data analysis, QC was carried out to check two factors to ensure data integrity. The first was comparing the area under the curve of the QC to the area under the curve of the process blank. Anything less than 1.5 was removed from analysis. Data were normalized to a reference value, transformed by the square root, and finally scaled with Pareto scaling. All values were adjusted for False Discovery Rate (FDR). After normalization, QC was used to evaluate the consistency of the data. This was carried out by measuring the percent coefficient of variation (%CV) (100 × standard deviation/mean). Metabolites with a %CV > 30% were removed from analysis.

- ➢

- Analysis of mass spectrometry data: Data was collected using SCIEX analyst software. Chromatogram integration was performed using SCIEX MultiQuant. Statistical analysis was performed using the Microsoft Excel Data Analysis add-in. Metabolite identity was established using a combination of an in-house metabolite library developed using pure purchased standards and the METLIN library. Normalization and QC were performed as described above for GC-MS. Values were adjusted for FDR. The report generated was then used for Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MetaboAnalyst), and the steps described above were followed to generate the top 25 enriched metabolites along with the enrichment ratio, and then associated p-values were generated. To ascertain changes in each individual metabolite between HETs and WTs, an unpaired, parametric Student’s t-test was utilized.

2.3. Glucose Assay

2.4. Glycogen Assay

2.5. Hexokinase (HK) Assay

2.6. Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) Assay

2.7. Hyperthermia Testing

2.8. Protein Assay

2.9. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for ΔFosB

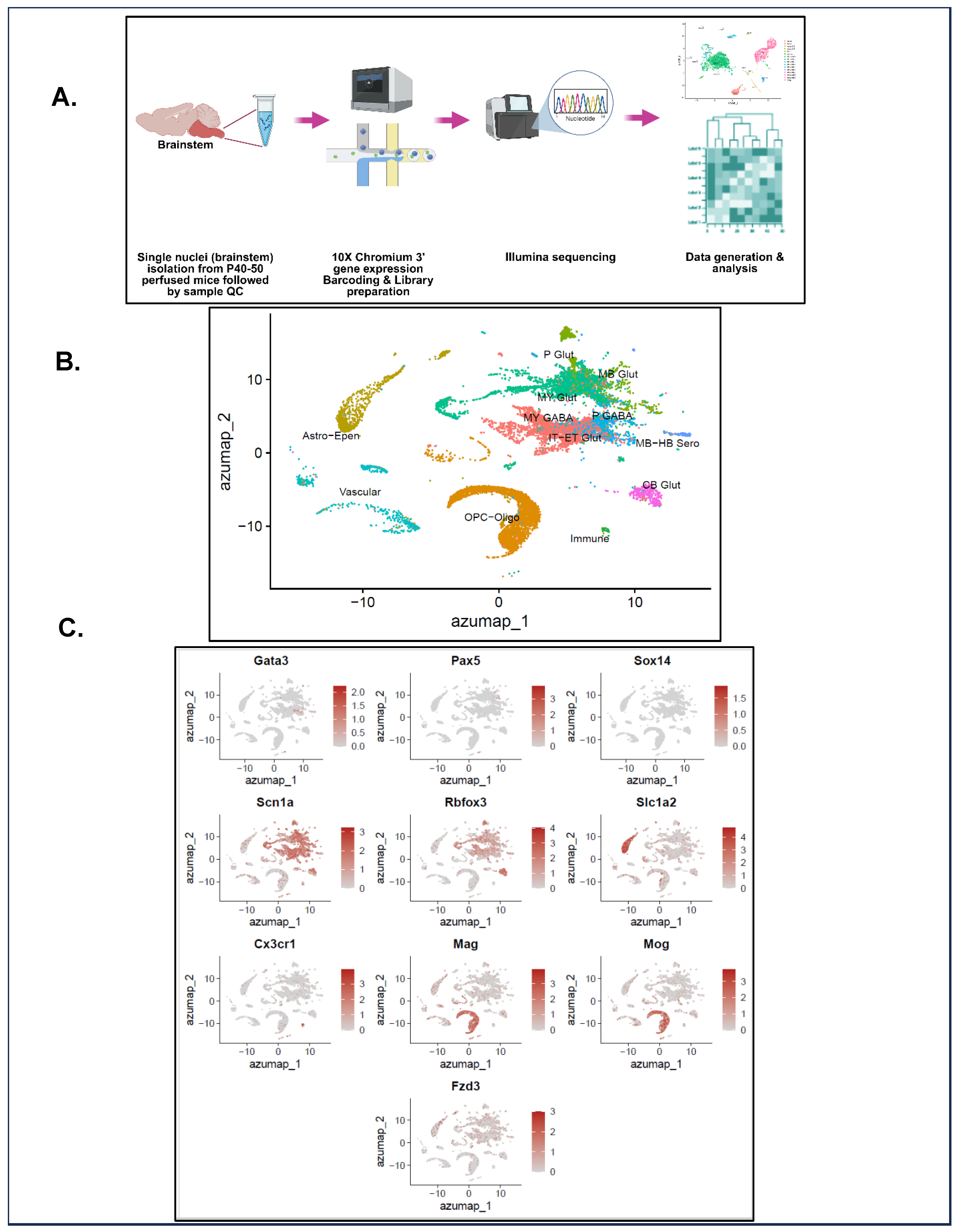

2.10. Single-Nuclei Preparation and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.11. Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Chemoproteomics

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study I: Metabolomic Analysis Reveals a Decrease in Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle Metabolites in the Forebrain of P20–30 HETs

3.2. Respiratory Nuclei Are Chronically Active in Several Brainstem Nuclei of HETs

3.3. Metabolomic Analyses (Studies I and II) Reveal an Overall Increase in Glycolytic and Energy Metabolism in the Brainstem of P20–30 HETs

3.4. Glutathione (GSH) and Aconitate Are Increased in the Brainstem of P40–50 HETs

3.5. Exploratory Single-Nuclei Sequencing (snRNA-seq) Unravels the Transcriptomes of P40–50 HETs and WTs

3.6. Genes Associated with Neurotransmission, Protein Translation, and Cellular Respiration Are Altered in the Brainstem of P40–50 HETs

3.7. MS-Based Preliminary Proteomic Analysis Identifies Druggable, Kinase-Mediated Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ngugi, A.K.; Bottomley, C.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Sander, J.W.; Newton, C.R. Estimation of the burden of active and life-time epilepsy: A meta-analytic approach. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dravet, C.; Oguni, H. Dravet syndrome (severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy). Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 111, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parihar, R.; Ganesh, S. The SCN1A gene variants and epileptic encephalopathies. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 58, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.S.; McIntosh, A.; Crompton, D.E.; McMahon, J.M.; Schneider, A.; Farrell, K.; Ganesan, V.; Gill, D.; Kivity, S.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; et al. Mortality in Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2016, 128, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange, I.M.; Gunning, B.; Sonsma, A.C.M.; van Gemert, L.; van Kempen, M.; Verbeek, N.E.; Sinoo, C.; Nicolai, J.; Knoers, N.; Koeleman, B.P.C.; et al. Outcomes and comorbidities of SCN1A-related seizure disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 90, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagae, L.; Brambilla, I.; Mingorance, A.; Gibson, E.; Battersby, A. Quality of life and comorbidities associated with Dravet syndrome severity: A multinational cohort survey. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2018, 60, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.M. Mechanisms of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.J.; Yousaf, M.I.K.; Shah, V.B. Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvlin, P.; Nashef, L.; Lhatoo, S.D.; Bateman, L.M.; Bird, J.; Bleasel, A.; Boon, P.; Crespel, A.; Dworetzky, B.A.; Hogenhaven, H.; et al. Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS): A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Bravo, E.; Thirnbeck, C.K.; Smith-Mellecker, L.A.; Kim, S.H.; Gehlbach, B.K.; Laux, L.C.; Zhou, X.; Nordli, D.R., Jr.; Richerson, G.B. Severe peri-ictal respiratory dysfunction is common in Dravet syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilella, L.; Lacuey, N.; Hampson, J.P.; Rani, M.R.S.; Sainju, R.K.; Friedman, D.; Nei, M.; Strohl, K.; Scott, C.; Gehlbach, B.K.; et al. Postconvulsive central apnea as a biomarker for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Neurology 2019, 92, e171–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, P.L. Cardiorespiratory Dysfunction Induced by Brainstem Spreading Depolarization: A Potential Mechanism for SUDEP. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 2387–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noebels, J.L. Brainstem spreading depolarization: Rapid descent into the shadow of SUDEP. Brain 2019, 142, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiba, I.; Noebels, J.L. Spreading depolarization in the brainstem mediates sudden cardiorespiratory arrest in mouse SUDEP models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 282ra246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, J.S.; Colangeli, R.; Wolff, M.D.; Wall, A.K.; Phillips, T.J.; George, A.; Federico, P.; Teskey, G.C. Postictal hypoperfusion/hypoxia provides the foundation for a unified theory of seizure-induced brain abnormalities and behavioral dysfunction. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, E.; Song, D.K.; Kim, M.S. Emerging role of the brain in the homeostatic regulation of energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.; Puchowicz, M.; Borges, K. Impairments in Oxidative Glucose Metabolism in Epilepsy and Metabolic Treatments Thereof. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress: Cause and consequence of epileptic seizures. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeland, O.B.; Hadera, M.G.; McDonald, T.S.; Sonnewald, U.; Borges, K. Brain Mitochondrial Metabolic Dysfunction and Glutamate Level Reduction in the Pilocarpine Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, W.H. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in human epilepsy. Adv. Neurol. 1999, 79, 873–881. [Google Scholar]

- Miljanovic, N.; van Dijk, R.M.; Buchecker, V.; Potschka, H. Metabolomic signature of the Dravet syndrome: A genetic mouse model study. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 2000–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depienne, C.; Trouillard, O.; Saint-Martin, C.; Gourfinkel-An, I.; Bouteiller, D.; Carpentier, W.; Keren, B.; Abert, B.; Gautier, A.; Baulac, S.; et al. Spectrum of SCN1A gene mutations associated with Dravet syndrome: Analysis of 333 patients. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, T.L.; Bomben, V.C.; Patel, A.; Drabek, J.; Chen, T.T.; Gu, W.; Zhang, F.; Chapman, K.; Lupski, J.R.; Noebels, J.L.; et al. High-resolution molecular genomic autopsy reveals complex sudden unexpected death in epilepsy risk profile. Epilepsia 2014, 55, e6–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabbout, R.; Gennaro, E.; Dalla Bernardina, B.; Dulac, O.; Madia, F.; Bertini, E.; Capovilla, G.; Chiron, C.; Cristofori, G.; Elia, M.; et al. Spectrum of SCN1A mutations in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Neurology 2003, 60, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Sun, H.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.W.; Wu, X.R. Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of SCN1A mutations in Dravet syndrome. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 2012, 29, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernici, C.D.; Mensah, J.A.; Dahle, E.J.; Johnson, K.J.; Handy, L.; Buxton, L.; Smith, M.D.; West, P.J.; Metcalf, C.S.; Wilcox, K.S. Development of an antiseizure drug screening platform for Dravet syndrome at the NINDS contract site for the Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernici, C.D.; Spink, A.; Dahle, E.J.; Johnson, K.J.; Metcalf, C.S.; West, P.J.; Wilcox, K.S. Evaluation of spontaneous seizure activity, sex-dependent differences, behavioral comorbidities, and alterations in CA1 neuron firing properties in a mouse model of Dravet Syndrome. bioRxiv 2021, 2021-06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricobaraza, A.; Mora-Jimenez, L.; Puerta, E.; Sanchez-Carpintero, R.; Mingorance, A.; Artieda, J.; Nicolas, M.J.; Besne, G.; Bunuales, M.; Gonzalez-Aparicio, M.; et al. Epilepsy and neuropsychiatric comorbidities in mice carrying a recurrent Dravet syndrome SCN1A missense mutation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkowski, M.; Lau, H.T.; Chan, M.; Kenerson, H.; Vidadala, V.N.; Shoemaker, A.; Maly, D.J.; Yeung, R.S.; Gujral, T.S.; Ong, S.E. Pharmacoproteomics Identifies Kinase Pathways that Drive the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Drug Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Syst. 2020, 11, 196–207.e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkowski, M.; Vidadala, V.N.; Lau, H.T.; Shoemaker, A.; Shimizu-Albergine, M.; Beavo, J.; Maly, D.J.; Ong, S.E. Kinobead/LC-MS Phosphokinome Profiling Enables Rapid Analyses of Kinase-Dependent Cell Signaling Networks. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkowski, M.; Lius, A.; Sapre, T.; Lau, H.T.; Moreno, T.; Maly, D.J.; Ong, S.E. Multiplexed kinase interactome profiling quantifies cellular network activity and plasticity. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 803–818.e808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.-J. Evaluation of a Potential Mechansim of SUDEP in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome; The University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, K.; Rants’o, T.A.; Chan, A.M.; Sapre, T.; Mastin, G.E.; Maguire, K.M.; Ong, S.-E.; Golkowski, M. diaPASEF-Powered Chemoproteomics Enables Deep Kinome Interaction Profiling. bioRxiv 2024, 2024-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, F.; Brunner, A.D.; Frank, M.; Ha, A.; Bludau, I.; Voytik, E.; Kaspar-Schoenefeld, S.; Lubeck, M.; Raether, O.; Bache, N.; et al. diaPASEF: Parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation combined with data-independent acquisition. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: Neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, K.; Mertins, P.; Zhang, B.; Hornbeck, P.; Raju, R.; Ahmad, R.; Szucs, M.; Mundt, F.; Forestier, D.; Jane-Valbuena, J.; et al. A Curated Resource for Phosphosite-specific Signature Analysis. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2019, 18, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsen, T.; de Vlieg, J.; Alkema, W. BioVenn—A web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzigaluppi, P.; Ebrahim Amini, A.; Weisspapir, I.; Stefanovic, B.; Carlen, P.L. Hungry Neurons: Metabolic Insights on Seizure Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, A.B.; do Canto, A.M.; Donatti, A.; Rosa, D.C.; Bruno, D.C.F.; Alvim, M.K.; Yasuda, C.L.; Martins, L.G.; Quintero, M.; Tasic, L.; et al. Circulating Metabolites as Biomarkers of Disease in Patients with Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Metabolites 2022, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuAlrob, M.A.; Tadi, P. Neuroanatomy, Nucleus Solitarius. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet, P.G.; Stornetta, R.L.; Abbott, S.B.; Depuy, S.D.; Kanbar, R. The retrotrapezoid nucleus and breathing. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 758, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millhorn, D.E.; Eldridge, F.L. Role of ventrolateral medulla in regulation of respiratory and cardiovascular systems. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986, 61, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiroi, N.; Marek, G.J.; Brown, J.R.; Ye, H.; Saudou, F.; Vaidya, V.A.; Duman, R.S.; Greenberg, M.E.; Nestler, E.J. Essential role of the fosB gene in molecular, cellular, and behavioral actions of chronic electroconvulsive seizures. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 6952–6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotti, L.I.; Hadeishi, Y.; Ulery, P.G.; Barrot, M.; Monteggia, L.; Duman, R.S.; Nestler, E.J. Induction of deltaFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10594–10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, G.S.; Park, J.; Eagle, A.; You, J.; Silva-Perez, M.; Fu, C.H.; Choi, S.; Romain, C.P.S.; Sugimoto, C.; Buffington, S.A.; et al. Persistent ∆FosB expression limits recurrent seizure activity and provides neuroprotection in the dentate gyrus of APP mice. Prog. Neurobiol. 2024, 237, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, F.S.; Cleary, C.M.; LoTurco, J.J.; Chen, X.; Mulkey, D.K. Disordered breathing in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Elife 2019, 8, e43387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Yao, J.; Rettberg, J.R.; Chen, S.; Brinton, R.D. Early decline in glucose transport and metabolism precedes shift to ketogenic system in female aging and Alzheimer’s mouse brain: Implication for bioenergetic intervention. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Alshakhshir, N.; Zhao, L. Glycolytic Metabolism, Brain Resilience, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 662242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choii, G.; Ko, J. Gephyrin: A central GABAergic synapse organizer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmler, M.; Gentier, R.J.; Dennissen, F.J.; Schulz, H.; Bolle, I.; Holter, S.M.; Kallnik, M.; Cheng, J.J.; Klingenspor, M.; Rozman, J.; et al. Long-term proteasomal inhibition in transgenic mice by UBB(+1) expression results in dysfunction of central respiration control reminiscent of brainstem neuropathology in Alzheimer patients. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 124, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivot, K.; Meszaros, G.; Pangou, E.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, M.; Erbs, E.; Yeghiazaryan, G.; Quinones, M.; Grandgirard, E.; Schneider, A.; et al. CaMK1D signalling in AgRP neurons promotes ghrelin-mediated food intake. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal, C.D.; Wang, C.Y.; Zuo, Z.; Smith, J.A.; Lindeke-Myers, A.; Bellen, H.J.; Lee, H.K. Daam2 Regulates Myelin Structure and the Oligodendrocyte Actin Cytoskeleton through Rac1 and Gelsolin. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montague, P.; McCallion, A.S.; Davies, R.W.; Griffiths, I.R. Myelin-Associated Oligodendrocytic Basic Protein: A Family of Abundant CNS Myelin Proteins in Search of a Function. Dev. Neurosci. 2006, 28, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, M.; Damseh, N.; de Sousa, M.M.L.; Jacob, F.; Lang, A.; Kristiansen, E.; Pannone, M.; Kissova, M.; et al. A loss-of-function mutation in human Oxidation Resistance 1 disrupts the spatial-temporal regulation of histone arginine methylation in neurodevelopment. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morré, D.J.; Morré, D.M. The ENOX Protein Family. In ECTO-NOX Proteins: Growth, Cancer, and Aging; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Yenari, M.A. Heat shock protein signaling in brain ischemia and injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 715, 134642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekutowska-Abramczuk, D.; Assouline, Z.; Matakovic, L.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Konarikova, E.; Jurkiewicz, E.; Stawinski, P.; Gusic, M.; Koller, A.; Pollak, A.; et al. NDUFB8 Mutations Cause Mitochondrial Complex I Deficiency in Individuals with Leigh-like Encephalomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, N.R.; AlDhaheri, N.S.; Ghosh, R.; Lim, J.; Streff, H.; Nayak, A.; Graham, B.H.; Hanchard, N.A.; Elsea, S.H.; Scaglia, F. Biallelic variants in COX4I1 associated with a novel phenotype resembling Leigh syndrome with developmental regression, intellectual disability, and seizures. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2019, 179, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Shukla, R. Dynamic Dysregulation of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Mouse Brain Stress Models. Stresses 2024, 4, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljanovic, N.; Hauck, S.M.; van Dijk, R.M.; Di Liberto, V.; Rezaei, A.; Potschka, H. Proteomic signature of the Dravet syndrome in the genetic Scn1a-A1783V mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 157, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the Dependency of Cellular Protein Levels on mRNA Abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.B.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chico, L.K.; Van Eldik, L.J.; Watterson, D.M. Targeting protein kinases in central nervous system disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, F.M.; Gray, N.S. Kinase inhibitors: The road ahead. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M. A Metabolic Paradigm for Epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2018, 18, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rho, J.M.; Boison, D. The metabolic basis of epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinger, H.; Hogg, J.P. Neuroanatomy, Brainstem. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Aglyamova, G.; Yim, Y.Y.; Bailey, A.O.; Lynch, H.M.; Powell, R.T.; Nguyen, N.D.; Rosenthal, Z.; Zhao, W.N.; Li, Y.; et al. Chemically targeting the redox switch in AP1 transcription factor DeltaFOSB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 9548–9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Vinet, J.; Curia, G.; Biagini, G. Repeated 6-Hz Corneal Stimulation Progressively Increases FosB/DeltaFosB Levels in the Lateral Amygdala and Induces Seizure Generalization to the Hippocampus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.F.; You, J.C.; Zhang, X.; Pyfer, M.S.; Tosi, U.; Iascone, D.M.; Petrof, I.; Hazra, A.; Fu, C.H.; Stephens, G.S.; et al. DeltaFosB Regulates Gene Expression and Cognitive Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, G.S.; Fu, C.H.; St Romain, C.P.; Zheng, Y.; Botterill, J.J.; Scharfman, H.E.; Liu, Y.; Chin, J. Genes Bound by DeltaFosB in Different Conditions with Recurrent Seizures Regulate Similar Neuronal Functions. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.C.; Muralidharan, K.; Park, J.W.; Petrof, I.; Pyfer, M.S.; Corbett, B.F.; LaFrancois, J.J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mohila, C.A.; et al. Epigenetic suppression of hippocampal calbindin-D28k by DeltaFosB drives seizure-related cognitive deficits. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, R.; Huynh, C.; Figueroa, F.; Dinday, M.T.; Baraban, S.C.; Patel, M. Enhancing glucose metabolism via gluconeogenesis is therapeutic in a zebrafish model of Dravet syndrome. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksendzovsky, A.; Bachani, M.; Altshuler, M.; Walbridge, S.; Mortazavi, A.; Moyer, M.; Chen, C.; Fayed, I.; Steiner, J.; Edwards, N.; et al. Chronic neuronal activation leads to elevated lactate dehydrogenase A through the AMP-activated protein kinase/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α hypoxia pathway. Brain Commun. 2022, 5, fcac298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, T.S.; Borges, K. Impaired hippocampal glucose metabolism during and after flurothyl-induced seizures in mice: Reduced phosphorylation coincides with reduced activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.; Garcia-Culebras, A.; Satta, V.; Hernandez-Fisac, I.; Sierra, A.; Guimare, J.A.; Lizasoain, I.; Fernandez-Ruiz, J.; Sagredo, O. Investigation in blood-brain barrier integrity and susceptibility to immune cell penetration in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 44, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.J.; Liang, C.L.; Li, G.M.; Yu, C.Y.; Yin, M. Stearic acid protects primary cultured cortical neurons against oxidative stress. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Li, G.M.; Tang, W.L.; Yin, M. Neuroprotective effects of stearic acid against toxicity of oxygen/glucose deprivation or glutamate on rat cortical or hippocampal slices. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2006, 27, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Miwa, T.; Sasaki, H.; Shibasaki, J.; Kaneto, H. Effect of straight chain fatty acids on seizures induced by picrotoxin and pentylenetetrazole in mice. J. Pharmacobiodyn 1990, 13, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Li, G.M.; Nie, B.M.; Lu, Y.; Yin, M. Neuroprotective effect of the stearic acid against oxidative stress via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyilmaz-Tiebe, D.; Pfaff, D.H.; Virtue, S.; Schwarz, K.V.; Fleming, T.; Altamura, S.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Okun, J.G.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Nawroth, P.; et al. Dietary stearic acid regulates mitochondria in vivo in humans. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siesjo, B.K.; Ingvar, M.; Westerberg, E. The influence of bicuculline-induced seizures on free fatty acid concentrations in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum. J. Neurochem. 1982, 39, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangos, P.J.; Trams, E.; Clark-Rosenberg, R.L.; Paul, S.M.; Skolnick, P. Anticonvulsant doses of inosine result in brain levels sufficient to inhibit [3H] diazepam binding. Psychopharmacology 1981, 75, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pougovkina, O.; te Brinke, H.; Ofman, R.; van Cruchten, A.G.; Kulik, W.; Wanders, R.J.A.; Houten, S.M.; de Boer, V.C.J. Mitochondrial protein acetylation is driven by acetyl-CoA from fatty acid oxidation. Human Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3513–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stincone, A.; Prigione, A.; Cramer, T.; Wamelink, M.M.; Campbell, K.; Cheung, E.; Olin-Sandoval, V.; Gruning, N.M.; Kruger, A.; Tauqeer Alam, M.; et al. The return of metabolism: Biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2015, 90, 927–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, H. Neuroprotective effects of oleic acid in rodent models of cerebral ischaemia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienel, G.A.; Gillinder, L.; McGonigal, A.; Borges, K. Potential new roles for glycogen in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haginoya, K.; Togashi, N.; Kaneta, T.; Hino-Fukuyo, N.; Ishitobi, M.; Kakisaka, Y.; Uematsu, M.; Inui, T.; Okubo, Y.; Sato, R.; et al. [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography study of genetically confirmed patients with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2018, 147, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boison, D.; Steinhauser, C. Epilepsy and astrocyte energy metabolism. Glia 2018, 66, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, G.A.; Cruz, N.F.; Sokoloff, L.; Driscoll, B.F. Determination of Glucose Utilization Rates in Cultured Astrocytes and Neurons with [(14)C]deoxyglucose: Progress, Pitfalls, and Discovery of Intracellular Glucose Compartmentation. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obel, L.F.; Müller, M.S.; Walls, A.B.; Sickmann, H.M.; Bak, L.K.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; Schousboe, A. Brain glycogen-new perspectives on its metabolic function and regulation at the subcellular level. Front. Neuroenergetics 2012, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, E.; Guidi, L.; Capellacci, S.; Ambrogini, P.; Papa, S.; Del Grande, P.; Ninfali, P. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase supports the functioning of the synapses in rat cerebellar cortex. Brain Res. 2001, 911, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgaard, I.; Li, B.; Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Sanggaard, S.; Haswell, J.D.; Sun, W.; Goldman, S.; Blekot, S.; Nielsen, M.; et al. Direct neuronal glucose uptake heralds activity-dependent increases in cerebral metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninfali, P.; Aluigi, G.; Pompella, A. Postnatal expression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in different brain areas. Neurochem. Res. 1998, 23, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, R.; Gerevich, Z.; Friedman, A.; Otahal, J.; Prager, O.; Gabriel, S.; Berndt, N. Bioenergetic Mechanisms of Seizure Control. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, D.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Li, L.; Fang, J.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; Peng, B.; Liu, W.; He, X. Long-term metabolic alterations in a febrile seizure model. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 126, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, S.R.; O’Brien, T.J.; Stefanidou, M.; Kuzniecky, R.I. Neuroimaging the epileptogenic process. Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dringen, R. Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000, 62, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Fiorello, M.L.; Bailey, D.M. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox. Biol. 2018, 15, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.S.; Hardingham, G.E. Adaptive regulation of the brain’s antioxidant defences by neurons and astrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 100, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.C.; Nejad, H.H.; Bottje, W.G.; Hassan, A.S. Glutathione Levels in Specific Brain-Regions of Genetically Epileptic (Tg/Tg) Mice. Brain Res. Bull. 1990, 25, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.G.; Trabesinger, A.H.; Boesiger, P.; Wieser, H.G. Brain glutathione levels in patients with epilepsy measured by in vivo1H-MRS. Neurology 2001, 57, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldbaum, S.; Liang, L.P.; Patel, M. Persistent impairment of mitochondrial and tissue redox status during lithium-pilocarpine-induced epileptogenesis. J. Neurochem. 2010, 115, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Hari, A.; Banerji, R.; Liang, L.P.; Fulton, R.E.; Huynh, C.Q.; Fabisiak, T.; McElroy, P.B.; Roede, J.R.; Patel, M. Increasing glutathione levels by a novel posttranslational mechanism inhibits neuronal hyperexcitability. Redox. Biol. 2023, 67, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewett, B.E.; Sharma, S. Physiology, GABA. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.G.; Rowley, S.; Fulton, R.; Dinday, M.T.; Baraban, S.C.; Patel, M. Altered Glycolysis and Mitochondrial Respiration in a Zebrafish Model of Dravet Syndrome. eNeuro 2016, 3, ENEURO.0008-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.K.; de Menezes, M.S.; Saneto, R.P. Dravet syndrome: Patients with co-morbid SCN1A gene mutations and mitochondrial electron transport chain defects. Seizure 2012, 21, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenina, N.; Bashammakh, S.; Bader, M. Specification and differentiation of serotonergic neurons. Stem. Cell Rev. 2006, 2, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Kalmbach, B.; Morishima, M.; Kim, J.; Juavinett, A.; Li, N.; Dembrow, N. Specialized Subpopulations of Deep-Layer Pyramidal Neurons in the Neocortex: Bridging Cellular Properties to Functional Consequences. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 5441–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Bland, B.H.; Antle, M.C. Nonserotonergic projection neurons in the midbrain raphe nuclei contain the vesicular glutamate transporter VGLUT3. Synapse 2009, 63, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebschull, J.M.; Richman, E.B.; Ringach, N.; Friedmann, D.; Albarran, E.; Kolluru, S.S.; Jones, R.C.; Allen, W.E.; Wang, Y.; Cho, S.W.; et al. Cerebellar nuclei evolved by repeatedly duplicating a conserved cell-type set. Science 2020, 370, eabd5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.; Rosch, R.E.; Hughes, E.; Ruben, P.C. Temperature-dependent changes in neuronal dynamics in a patient with an SCN1A mutation and hyperthermia induced seizures. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, D.A.; Ma, Z.; Horrocks, J.; Rogers, A.N. Stress-induced Eukaryotic Translational Regulatory Mechanisms. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, N.; Przybyla, M.; van der Hoven, J.; Ke, Y.D.; Delerue, F.; van Eersel, J.; Ittner, L.M. Treatment of epilepsy using a targeted p38gamma kinase gene therapy. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, F.Y.; Chi, S.; Liu, T.; Yang, H.L.; Zhong, R.J.; Li, X.Y.; Gao, J. Mitochondria-targeting peptide SS-31 attenuates ferroptosis via inhibition of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in the hippocampus of epileptic rats. Brain Res. 2024, 1836, 148882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enomoto, A.; Kido, N.; Ito, M.; Takamatsu, N.; Miyagawa, K. Serine-threonine kinase 38 is regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and modulates oxidative stress-induced cell death. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jope, R.S.; Cheng, Y.; Lowell, J.A.; Worthen, R.J.; Sitbon, Y.H.; Beurel, E. Stressed and Inflamed, Can GSK3 Be Blamed? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Zhu, H.; Sheng, F.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, J. Activation of the MAPK11/12/13/14 (p38 MAPK) pathway regulates the transcription of autophagy genes in response to oxidative stress induced by a novel copper complex in HeLa cells. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1285–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, E.; Vegliante, R.; Cardaci, S.; Nepravishta, R.; Paci, M.; Ciriolo, M.R. MAPK14/p38α-dependent modulation of glucose metabolism affects ROS levels and autophagy during starvation. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1652–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, C.; Codogno, P.; Fanto, M.; Hergovich, A.; Camonis, J. STK38 at the crossroad between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy 2016, 12, 594–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katholnig, K.; Kaltenecker, C.C.; Hayakawa, H.; Rosner, M.; Lassnig, C.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Gaestel, M.; Müller, M.; Hengstschläger, M.; Hörl, W.H.; et al. p38α senses environmental stress to control innate immune responses via mechanistic target of rapamycin. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.A.; Souder, D.C.; Miller, K.N.; Clark, J.P.; Sagar, A.K.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Puglielli, L.; Beasley, T.M.; Anderson, R.M. GSK3β Regulates Brain Energy Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1922–1931.e1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Dai, G.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.; Ma, T.; Wang, N.; Gu, J.; Wang, Y. Integrating Proteomics and Transcriptomics Reveals the Potential Pathways of Hippocampal Neuron Apoptosis in Dravet Syndrome Model Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aourz, N.; Serruys, A.K.; Chabwine, J.N.; Balegamire, P.B.; Afrikanova, T.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Grey, A.I.; Kamuhabwa, A.R.; Walrave, L.; Esguerra, C.V.; et al. Identification of GSK-3 as a Potential Therapeutic Entry Point for Epilepsy. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 1992–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sri Hari, A.; Chan, A.M.; Scholl, A.; Mulligan, A.; Camacho, J.; Kearns, I.R.; Opazo, G.V.; Cheminant, J.; Musci, T.; Goh, M.-J.; et al. Multiomic Analyses Reveal Brainstem Metabolic Changes in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. Cells 2026, 15, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010067

Sri Hari A, Chan AM, Scholl A, Mulligan A, Camacho J, Kearns IR, Opazo GV, Cheminant J, Musci T, Goh M-J, et al. Multiomic Analyses Reveal Brainstem Metabolic Changes in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. Cells. 2026; 15(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleSri Hari, Ashwini, Alexandria M. Chan, Audrey Scholl, Aidan Mulligan, Janint Camacho, Ireland Rose Kearns, Gustavo Vasquez Opazo, Jenna Cheminant, Teresa Musci, Min-Jee Goh, and et al. 2026. "Multiomic Analyses Reveal Brainstem Metabolic Changes in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome" Cells 15, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010067

APA StyleSri Hari, A., Chan, A. M., Scholl, A., Mulligan, A., Camacho, J., Kearns, I. R., Opazo, G. V., Cheminant, J., Musci, T., Goh, M.-J., Venosa, A., Moos, P. J., Golkowski, M., & Metcalf, C. S. (2026). Multiomic Analyses Reveal Brainstem Metabolic Changes in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. Cells, 15(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010067