Protein Kinase A Signaling in Cortisol Production and Adrenal Cushing’s Syndrome

Highlights

- Disruptions to cAMP/PKA signaling in adrenal cells can cause chronically elevated cortisol levels, known as Cushing’s syndrome.

- Synthesis of the mutations and their impacts suggests that elevated and/or ectopic PKA activity drives pathology, including augmented cell proliferation and overactive cholesterol processing.

- Elucidation of the specific roles for type I versus type II PKA, as well as which subcellular populations of the kinase control cortisol production and proliferation, will lead to improved understanding of pathology.

Abstract

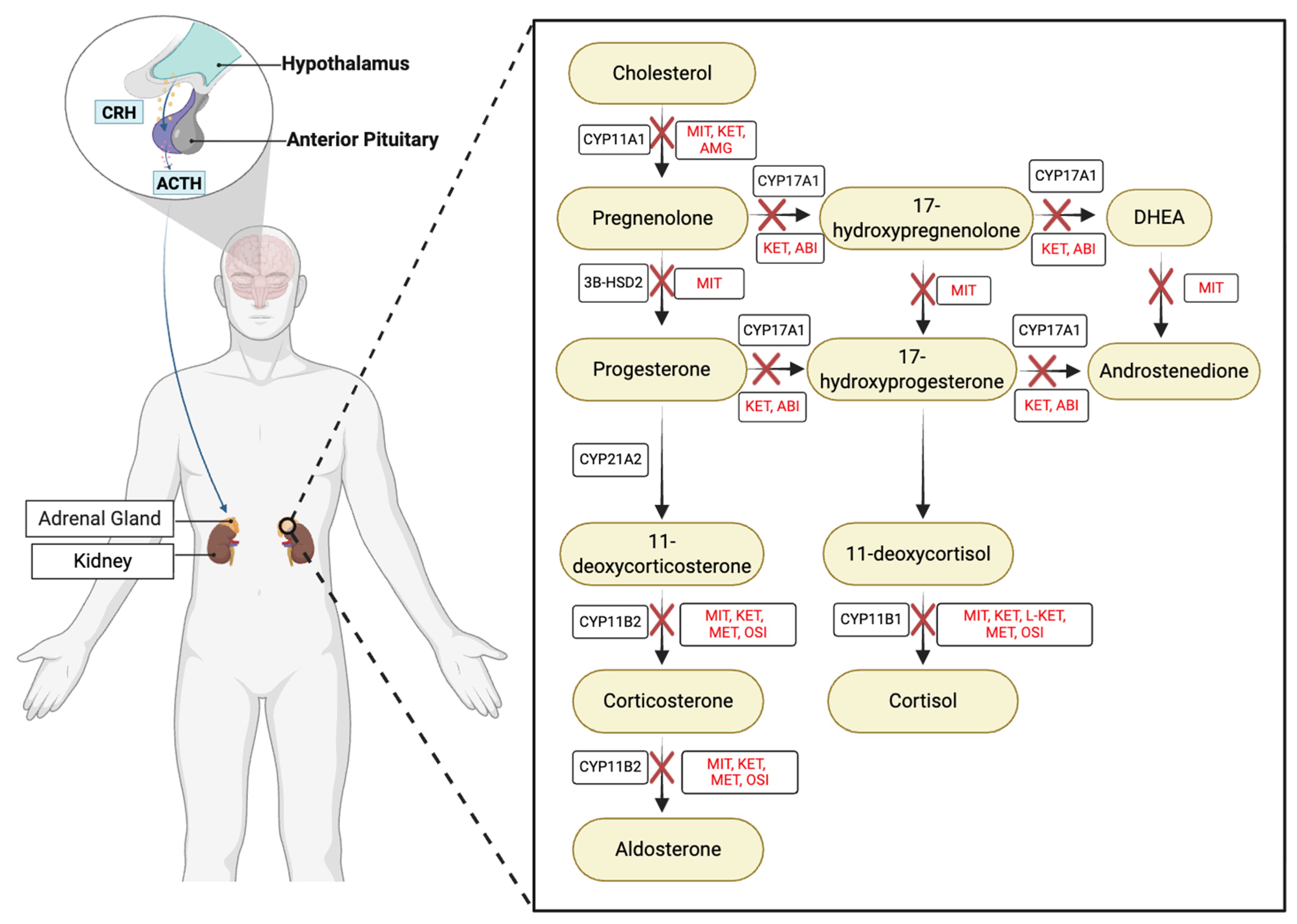

1. Cortisol in Health and Disease

2. Mechanisms of Protein Kinase A Signaling

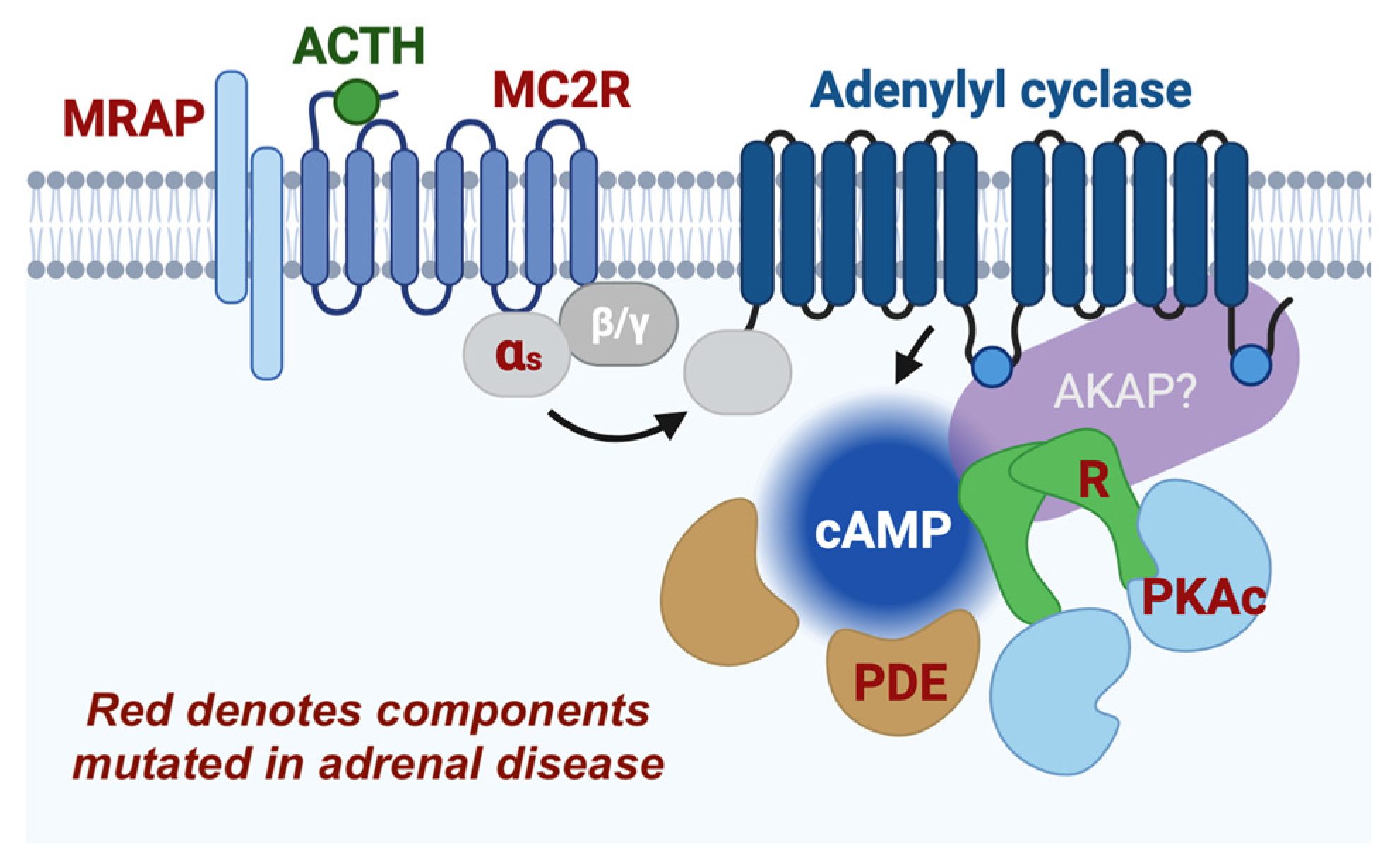

3. PKA Is a Vital Component of Cortisol Production

4. PKA and StAR

5. cAMP Signaling in Adrenal Disease

6. Receptor Complexes

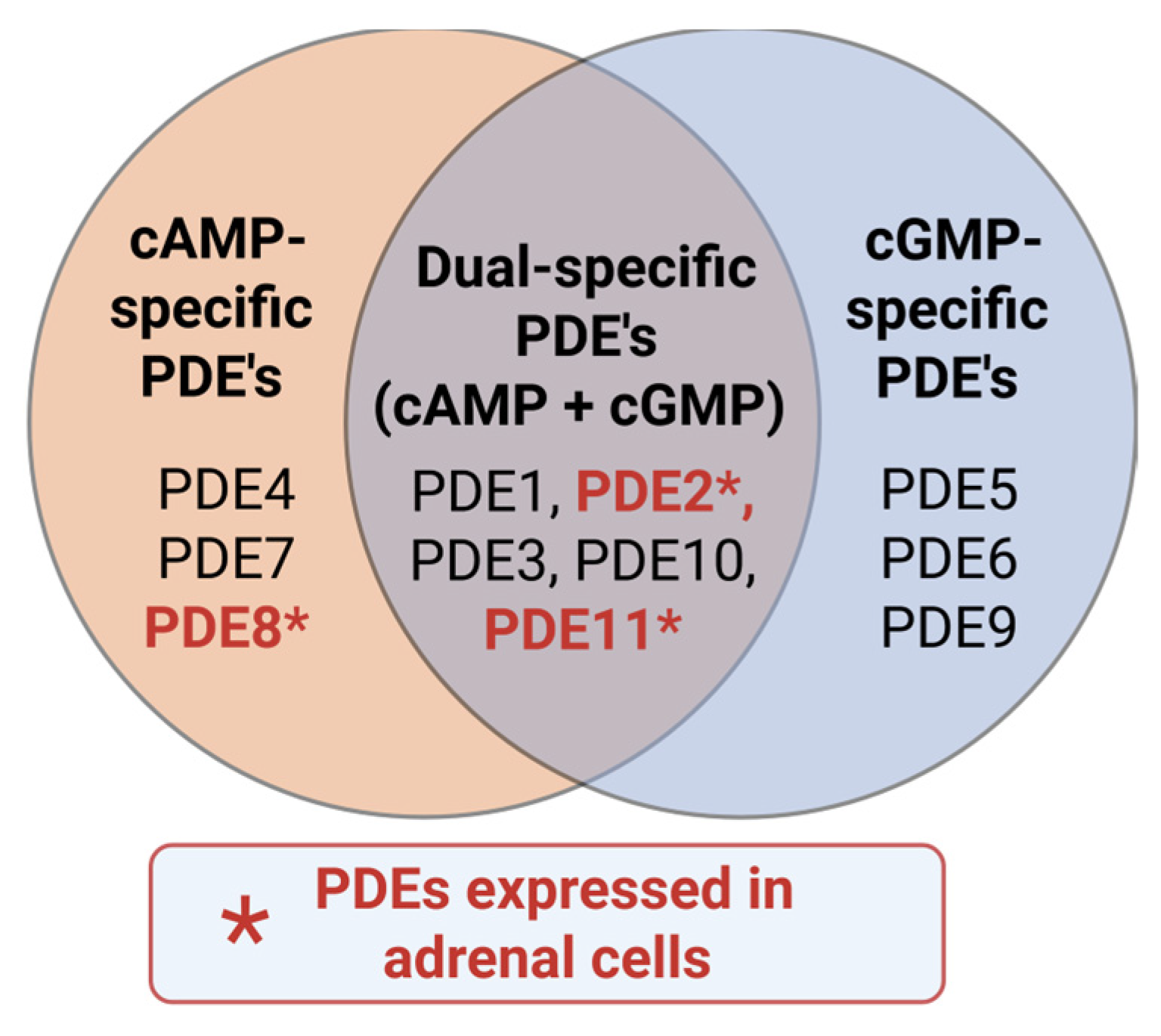

7. Phosphodiesterases

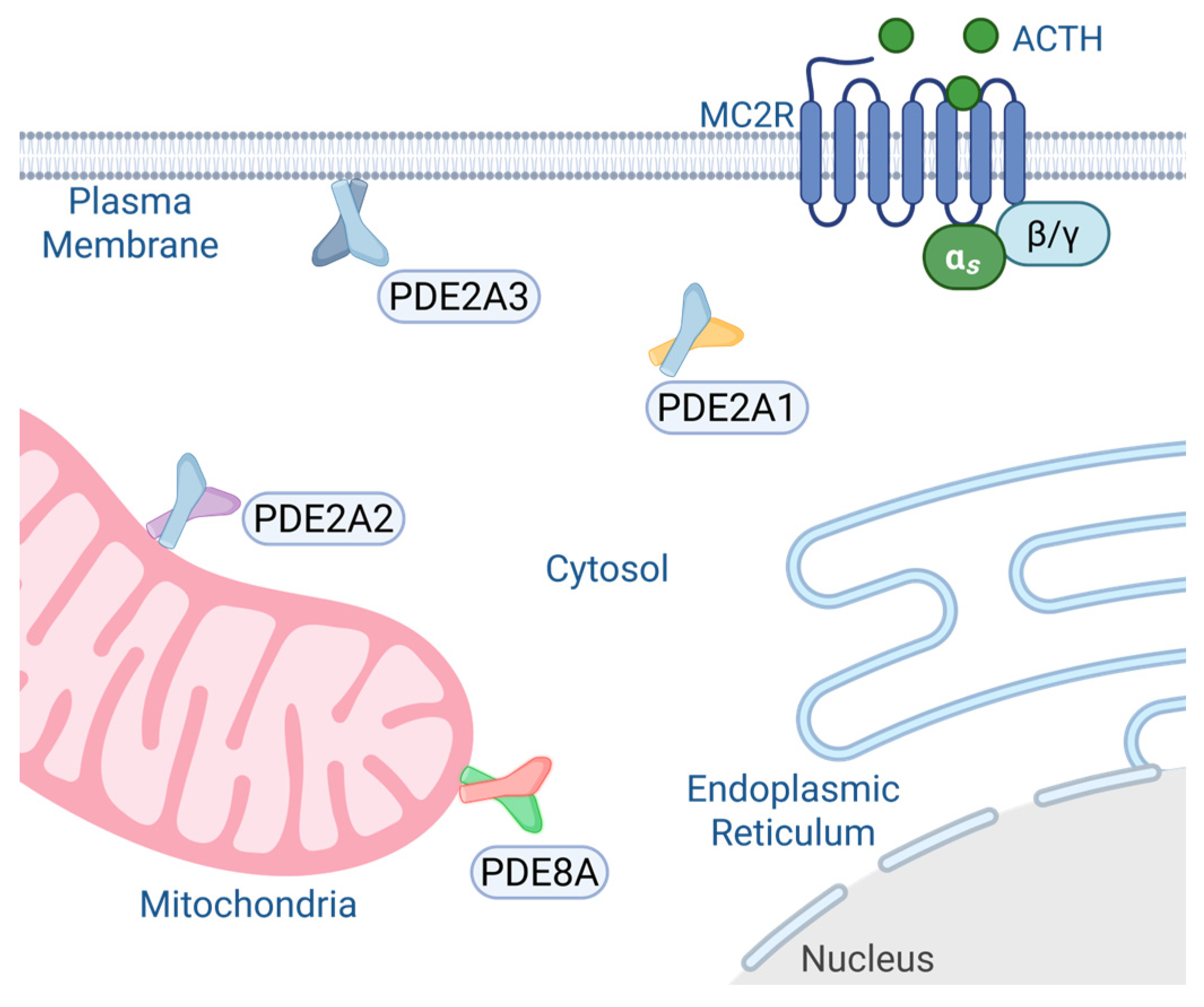

7.1. PDE2A

7.2. PDE8A/B

7.3. PDE11

8. β-Catenin

9. PKA Regulatory Subunit Roles in Cushing’s Syndrome

10. PKA Catalytic Subunit Mutations in Cushing’s Syndrome

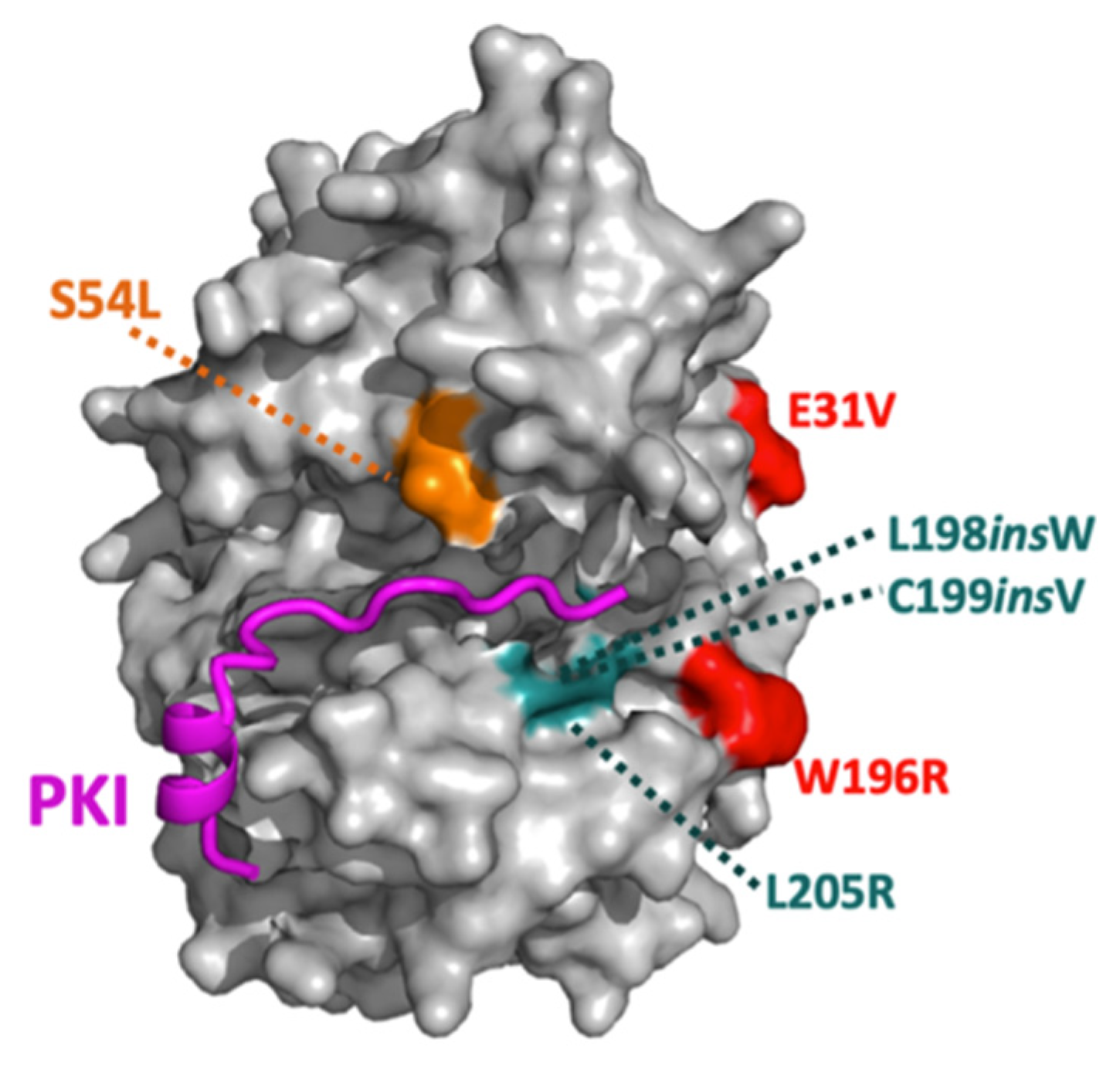

| Mutations | Inhibitory Interactions | Signaling Disruptions |

|---|---|---|

| E31V | RI inhibition weakly to not disrupted | |

| W196R | RI inhibition moderately disrupted; RII inhibition strongly disrupted | Upregulated pERK and decreased YAP/TAZ levels (cells and knock-in mice); increased RIα and decreased RIIβ levels (cells and knock-in mice); increased StAR levels (cells) |

| W196G | RI inhibition weakly disrupted; RII inhibition strongly disrupted | Increased RIα levels (patient tissue) |

| L198insW | RI, RII, and PKI inhibitions strongly disrupted | |

| C199insV | RI and PKI inhibitions strongly disrupted; RII inhibition moderately disrupted | |

| L205R | RI, RII, and PKI inhibitions strongly disrupted | Increased YAP/TAZ levels, increased histone H1.4 phosphorylation, increased StAR levels (cells and patient tissue); decreased RII levels (cells and patient tissue) |

| S212R + insIILR | RI and RII inhibitions strongly disrupted; no data on PKI | |

| del243–247 + E248Q | RI and RII inhibitions strongly disrupted; no data on PKI | |

| S53L (PKAcβ) | RI and PKI inhibitions moderately disrupted |

11. Other cAMP Effectors

12. Closing Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charmandari, E.; Tsigos, C.; Chrousos, G. Endocrinology of the Stress Response. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005, 67, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, N.A.; Yuen, F.; Butt, W.Z.; Liu, P.Y. Sleep and Circadian Regulation of Cortisol: A Short Review. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2021, 18, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell-Price, J.; Bertagna, X.; Grossman, A.B.; Nieman, L.K. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet 2006, 367, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Hu, Z.; Lü, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Chronic Glucocorticoid Exposure Induces Depression-Like Phenotype in Rhesus Macaque (Macaca Mulatta). Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, A.; Feelders, R.A.; Stratakis, C.A.; Nieman, L.K. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reincke, M.; Fleseriu, M. Cushing Syndrome: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, L.K.; Biller, B.M.; Findling, J.W.; Murad, M.H.; Newell-Price, J.; Savage, M.O.; Tabarin, A. Treatment of Cushing’s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 2807–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, L.K.; Castinetti, F.; Newell-Price, J.; Valassi, E.; Drouin, J.; Takahashi, Y.; Lacroix, A. Cushing syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savas, M.; Mehta, S.; Agrawal, N.; van Rossum, E.F.C.; Feelders, R.A. Approach to the Patient: Diagnosis of Cushing Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 3162–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, M.; Ceccato, F.; Scaroni, C. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Hypertension in Patients with Cushing’s Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, S.; Perini, A.M.E.; Botto, C.; Oliva, F.; Terzolo, M. Long-Term Consequences of Cushing Syndrome: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e901–e919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, O.M.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; Jørgensen, J.O.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Ehrenstein, V.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Pereira, A.M.; Sørensen, H.T. Multisystem morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome: A cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broersen, L.H.A.; Jha, M.; Biermasz, N.R.; Pereira, A.M.; Dekkers, O.M. Effectiveness of medical treatment for Cushing’s syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pituitary 2018, 21, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalla, G.K.; Arzt, E.; Losa, M.; Renner, U. Editorial: Current Clinical and Pre-Clinical Progress in Cushing’s Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 612321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäger, M.-C.; Kędzierski, J.; Gell, V.; Wey, T.; Kollár, J.; Winter, D.V.; Schuster, D.; Smieško, M.; Odermatt, A. Virtual screening and biological evaluation to identify pharmaceuticals potentially causing hypertension and hypokalemia by inhibiting steroid 11β-hydroxylase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 475, 116638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleseriu, M.; Castinetti, F. Updates on the role of adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors in Cushing’s syndrome: A focus on novel therapies. Pituitary 2016, 19, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, C.; Lalli, E. Impact of ACTH Signaling on Transcriptional Regulation of Steroidogenic Genes. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmer, B.P. The 1994 Upjohn Award Lecture. Molecular and genetic approaches to the study of signal transduction in the adrenal cortex. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995, 73, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Fischer, E.H.; Demaille, J.G.; Krebs, E.G. Identification of an inhibitory region of the heat-stable protein inhibitor of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 4379–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.D.; Glaccum, M.B.; Fischer, E.H.; Krebs, E.G. Primary-structure requirements for inhibition by the heat-stable inhibitor of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 1613–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.A.; Ashby, C.D.; Gonzalez, C.; Calkins, D.; Fischer, E.H. Krebs EG: Purification and characterization of a protein inhibitor of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabb, J.B. Physiological substrates of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2381–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnham, R.E.; Scott, J.D. Protein kinase A catalytic subunit isoform PRKACA; History, function and physiology. Gene 2016, 577, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, I.C.; Huang, W.J.; Jhuang, Y.L.; Chang, Y.Y.; Hsu, H.P.; Jeng, Y.M. Microinsertions in PRKACA cause activation of the protein kinase A pathway in cardiac myxoma. J. Pathol. 2017, 242, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbach, F.; Stoyanov, G.; Erger, F.; Stratakis, C.A.; Settas, N.; London, E.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Torti, E.; Haldeman-Englert, C.; Sklirou, E.; et al. Variants in PRKAR1B cause a neurodevelopmental disorder with autism spectrum disorder, apraxia, and insensitivity to pain. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, G.B. The cAMP-signaling cancers: Clinically-divergent disorders with a common central pathway. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1024423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.H.; Scott, J.D. AKAP Signaling Islands: Venues for Precision Pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.S.; Ilouz, R.; Zhang, P.; Kornev, A.P. Assembly of allosteric macromolecular switches: Lessons from PKA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.S.; Wallbott, M.; Machal, E.M.F.; Søberg, K.; Ahmed, F.; Bruystens, J.; Vu, L.; Baker, B.; Wu, J.; Raimondi, F.; et al. PKA Cβ: A forgotten catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase opens new windows for PKA signaling and disease pathologies. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 2101–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.D.; Reichow, S.L.; Esseltine, J.L.; Shi, D.; Langeberg, L.K.; Scott, J.D.; Gonen, T. Intrinsic disorder within an AKAP-protein kinase A complex guides local substrate phosphorylation. eLife 2013, 2, e01319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.D.; Esseltine, J.L.; Nygren, P.J.; Veesler, D.; Byrne, D.P.; Vonderach, M.; Strashnov, I.; Eyers, C.E.; Eyers, P.A.; Langeberg, L.K.; et al. Local protein kinase A action proceeds through intact holoenzymes. Science 2017, 356, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, Z.; Hernández-Ochoa, E.O.; Pratt, S.J.P.; Liu, Y.; Pierce, A.D.; Wilder, P.T.; Adipietro, K.A.; Breysse, D.H.; Varney, K.M.; Schneider, M.F.; et al. The Activation of Protein Kinase A by the Calcium-Binding Protein S100A1 Is Independent of Cyclic AMP. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happ, J.T.; Arveseth, C.D.; Bruystens, J.; Bertinetti, D.; Nelson, I.B.; Olivieri, C.; Zhang, J.; Hedeen, D.S.; Zhu, J.F.; Capener, J.L.; et al. A PKA inhibitor motif within SMOOTHENED controls Hedgehog signal transduction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 29, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, T.A.; Correll, L.A.; McKnight, G.S.; Corbin, J.D. Expression and characterization of mutant forms of the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. The effect of defective cAMP binding on holoenzyme activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 13321–13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, A.D.; McKnight, G.S. Overexpression of the type II regulatory subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase eliminates the type I holoenzyme in mouse cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 20255–20260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stakkestad, Ø.; Larsen, A.C.; Kvissel, A.K.; Eikvar, S.; Ørstavik, S.; Skålhegg, B.S. Protein kinase A type I activates a CRE-element more efficiently than protein kinase A type II regardless of C subunit isoform. BMC Biochem 2011, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.K.L.; Maisel, S.; Hwang, Y.C.; Pascual, B.C.; Wolber, R.R.B.; Vu, P.; Patra, K.C.; Bouhaddou, M.; Kenerson, H.L.; Lim, H.C.; et al. Oncogenic PKA signaling increases c-MYC protein expression through multiple targetable mechanisms. eLife 2023, 12, e69521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, D.W.; Stofko-Hahn, R.E.; Fraser, I.D.; Bishop, S.M.; Acott, T.S.; Brennan, R.G.; Scott, J.D. Interaction of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase with RII-anchoring proteins occurs through an amphipathic helix binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 14188–14192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberg, F.W.; Maleszka, A.; Eide, T.; Vossebein, L.; Tasken, K. Analysis of A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) interaction with protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunits: PKA isoform specificity in AKAP binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 298, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.C., Jr. The activation of adrenal phosphorylase by the adrenocorticotropic hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.C., Jr.; Koritz, S.B.; Peron, F.G. Influence of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate on corticoid production by rat adrenal glands. J. Biol. Chem. 1959, 234, 1421–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahame-Smith, D.G.; Butcher, R.W.; Ney, R.L.; Sutherland, E.W. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate as the intracellular mediator of the action of adrenocorticotropic hormone on the adrenal cortex. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 5535–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garren, L.D. The mechanism of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone. Vitam. Horm. 1969, 26, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunton, O.D.; Roth, J.; Pastan, I. ACTH stimulation of adenyl cyclase in adrenal homogenates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garren, L.D.; Ney, R.L.; Davis, W.W. Studies on the role of protein synthesis in the regulation of corticosterone production by adrenocorticotropic hormone in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1965, 53, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.A.; Perkins, J.P.; Krebs, E.G. An adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependant protein kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1968, 243, 3763–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garren, L.D.; Gill, G.N.; Walton, G.M. The isolation of a receptor for adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) from the adrenal cortex: The role of the receptor in the mechanism of action of cAMP. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1971, 185, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, P.A.; Gutmann, N.S.; Tsao, J.; Schimmer, B.P. Mutations in cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and corticotropin (ACTH)-sensitive adenylate cyclase affect adrenal steroidogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, G.M.; Gill, G.N. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and protein kinase dependent phosphorylation of ribosomal protein. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 2604–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podesta, E.J.; Milani, A.; Steffen, H.; Neher, R. Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) induces phosphorylation of a cytoplasmic protein in intact isolated adrenocortical cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 5187–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, J.A.; Green, E.G.; Mortensen, R.M.; Menachery, A.; Williams, G.H.; Orme-Johnson, N.R. Comparison of protein phosphorylation patterns produced in adrenal cells by activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca-dependent protein kinase. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995, 53, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakane, F.; King, S.R.; Du, Y.; Kallen, C.B.; Walsh, L.P.; Watari, H.; Stocco, D.M.; Strauss, J.F. Phosphorylation of Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein (StAR) Modulates Its Steroidogenic Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 32656–32662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumura, Y.; Buonassisi, V.; Sato, G. Clonal analysis of differentiated function in animal cell cultures. I. Possible correlated maintenance of differentiated function and the diploid karyotype. Cancer Res. 1966, 26, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.; Krolczyk, A.J.; Schimmer, B.P. The causal relationship between mutations in cAMP-dependent protein kinase and the loss of adrenocorticotropin-regulated adrenocortical functions. Mol. Endocrinol. 1992, 6, 1614–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.F.; Krolczyk, A.J.; Gorman, K.B.; Steinberg, R.A.; Schimmer, B.P. Molecular basis for the 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate resistance of Kin mutant Y1 adrenocortical tumor cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1993, 7, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.J.; Orme-Johnson, N.R. Acute adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation of adrenal corticosteroidogenesis. Discovery of a rapidly induced protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 10159–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pon, L.A.; Hartigan, J.A.; Orme-Johnson, N.R. Acute ACTH regulation of adrenal corticosteroid biosynthesis. Rapid accumulation of a phosphoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 13309–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberta, J.A.; Epstein, L.F.; Pon, L.A.; Orme-Johnson, N.R. Mitochondrial localization of a phosphoprotein that rapidly accumulates in adrenal cortex cells exposed to adrenocorticotropic hormone or to cAMP. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 2368–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pon, L.A.; Epstein, L.F.; Orme-Johnson, N.R. Acute cAMP stimulation in Leydig cells: Rapid accumulation of a protein similar to that detected in adrenal cortex and corpus luteum. Endocr. Res. 1986, 12, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, L.R.; Stocco, D.M. Effect of different steroidogenic stimuli on protein phosphorylation and steroidogenesis in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1991, 1094, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocco, D.M. Further evidence that the mitochondrial proteins induced by hormone stimulation in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells are involved in the acute regulation of steroidogenesis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, D.M.; Clark, B.J. The requirement of phosphorylation on a threonine residue in the acute regulation of steroidogenesis in MA-10 mouse Leydig cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993, 46, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.J.; Wells, J.; King, S.R.; Stocco, D.M. The purification, cloning, and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR). J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 28314–28322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, G.; Zubair, M.; Ishii, T.; Mitsui, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Auchus, R.J. The contribution of serine 194 phosphorylation to steroidogenic acute regulatory protein function. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M.T.; Jones, J.K.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Manna, P.R.; Alonso, M.; Gottesman, M.E.; Stocco, D.M. Mitochondrial A-kinase anchoring protein 121 binds type II protein kinase A and enhances steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-mediated steroidogenesis in MA-10 mouse leydig tumor cells. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 78, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grozdanov, P.N.; Stocco, D.M. Short RNA molecules with high binding affinity to the KH motif of A-kinase anchoring protein 1 (AKAP1): Implications for the regulation of steroidogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 2104–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M.T.; Kowalewski, M.P.; Manna, P.R.; Stocco, D.M. The differential regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein-mediated steroidogenesis by type I and type II PKA in MA-10 cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 300, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogreid, D.; Ekanger, R.; Suva, R.H.; Miller, J.P.; Døskeland, S.O. Comparison of the two classes of binding sites (A and B) of type I and type II cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinases by using cyclic nucleotide analogs. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989, 181, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronde, E.; Wicht, H.; Taskén, K.; Genieser, H.-G.; Dehghani, F.; Olcese, J.; Korf, H.-W. CREB phosphorylation and melatonin biosynthesis in the rat pineal gland: Involvement of cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase type II. J. Pineal Res. 1999, 27, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A.E.; Selheim, F.; de Rooij, J.; Dremier, S.; Schwede, F.; Dao, K.K.; Martinez, A.; Maenhaut, C.; Bos, J.L.; Genieser, H.G.; et al. cAMP analog mapping of Epac1 and cAMP kinase. Discriminating analogs demonstrate that Epac and cAMP kinase act synergistically to promote PC-12 cell neurite extension. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 35394–35402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poderoso, C.; Converso, D.P.; Maloberti, P.; Duarte, A.; Neuman, I.; Galli, S.; Cornejo Maciel, F.; Paz, C.; Carreras, M.C.; Poderoso, J.J.; et al. A mitochondrial kinase complex is essential to mediate an ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of a key regulatory protein in steroid biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, N.G.; Trester-Zedlitz, M.; Newton, B.W.; Peng, G.E.; Johnson, J.R.; Jimenez-Morales, D.; Kurland, A.P.; Krogan, N.J.; von Zastrow, M. Endosomal cAMP production broadly impacts the cellular phosphoproteome. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, S.E.; Kayser, C.; Maiellaro, I.; Nemec, K.; Möller, J.; Koschinski, A.; Zaccolo, M.; Annibale, P.; Falcke, M.; Lohse, M.J.; et al. Receptor-associated independent cAMP nanodomains mediate spatiotemporal specificity of GPCR signaling. Cell 2022, 185, 1130–1142.e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, A.; Maudhoo, A.; Chan, L.F.; Novoselova, T.; Prasad, R.; Metherell, L.A.; Guasti, L. Isolated glucocorticoid deficiency: Genetic causes and animal models. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 189, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.Q.; Azevedo, M.F.; Xekouki, P.; Bimpaki, E.I.; Horvath, A.; Collins, M.T.; Karaviti, L.P.; Jeha, G.S.; Bhattacharyya, N.; Cheadle, C.; et al. Activation of cyclic AMP signaling leads to different pathway alterations in lesions of the adrenal cortex caused by germline PRKAR1A defects versus those due to somatic GNAS mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E687–E693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, A.; Ndiaye, N.; Tremblay, J.; Hamet, P. Ectopic and abnormal hormone receptors in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, L.S.; Shenker, A.; Gejman, P.V.; Merino, M.J.; Friedman, E.; Spiegel, A.M. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, C.; Ashida, K.; Kohashi, K.; Ohe, K.; Fujii, Y.; Yano, S.; Matsuda, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Sakamoto, R.; Oda, Y.; et al. A case of autonomous cortisol secretion in a patient with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome, GNAS mutation, and paradoxical cortisol response to dexamethasone. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2019, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takedani, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Tanaka, S.; Ishihara, S.; Taketani, T.; Kanasaki, K. ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic endocrinologically functional adrenal tissue caused by a GNAS heterozygous mutation: A rare case of McCune-Albright syndrome accompanied by central amenorrhea and hypothyroidism: A case report and literature review. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 934748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Maekawa, S.; Ishii, R.; Sanada, M.; Morikawa, T.; Shiraishi, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Nagata, Y.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Yoshizato, T.; et al. Recurrent somatic mutations underlie corticotropin-independent Cushing’s syndrome. Science 2014, 344, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Shokat, K.M. Disease-Causing Mutations in the G Protein Gαs Subvert the Roles of GDP and GTP. Cell 2018, 173, 1254–1264.e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omori, K.; Kotera, J. Overview of PDEs and Their Regulation. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.R.; Clancy, C.E.; Harvey, R.D. Mechanisms Restricting Diffusion of Intracellular cAMP. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Arcangelis, V.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Soto, D.; Xiang, Y.K. Equilibrium between adenylyl cyclase and phosphodiesterase patterns adrenergic agonist dose-dependent spatiotemporal cAMP/protein kinase A activities in cardiomyocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 78, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musheshe, N.; Schmidt, M.; Zaccolo, M. cAMP: From Long-Range Second Messenger to Nanodomain Signalling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, M.F.; Faucz, F.R.; Bimpaki, E.; Horvath, A.; Levy, I.; de Alexandre, R.B.; Ahmad, F.; Manganiello, V.; Stratakis, C.A. Clinical and Molecular Genetics of the Phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 195–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, L.C.; Shimizu-Albergine, M.; Beavo, J.A. The high-affinity cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase 8B controls steroidogenesis in the mouse adrenal gland. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 79, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, A.; Boikos, S.; Giatzakis, C.; Robinson-White, A.; Groussin, L.; Griffin, K.J.; Stein, E.; Levine, E.; Delimpasi, G.; Hsiao, H.P.; et al. A genome-wide scan identifies mutations in the gene encoding phosphodiesterase 11A4 (PDE11A) in individuals with adrenocortical hyperplasia. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakics, V.; Karran, E.H.; Boess, F.G. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology 2010, 59, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A.; Mericq, V.; Stratakis, C.A. Mutation in PDE8B, a cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase in adrenal hyperplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 750–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah-Shmouni, F.; Faucz, F.R.; Stratakis, C.A. Alterations of Phosphodiesterases in Adrenocortical Tumors. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, M.J.; Reverte-Salisa, L.; Chao, Y.C.; Koschinski, A.; Gesellchen, F.; Subramaniam, G.; Jiang, H.; Pace, S.; Larcom, N.; Paolocci, E.; et al. Phosphodiesterase 2A2 regulates mitochondria clearance through Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bähr, V.; Sander-Bähr, C.; Ardevol, R.; Tuchelt, H.; Beland, B.; Oelkers, W. Effects of atrial natriuretic factor on the renin-aldosterone system: In vivo and in vitro studies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993, 45, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, S.E.; Wu, A.Y.; Glavas, N.A.; Tang, X.B.; Turley, S.; Hol, W.G.; Beavo, J.A. The two GAF domains in phosphodiesterase 2A have distinct roles in dimerization and in cGMP binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13260–13265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, J.; Lampron, A.; Mazzuco, T.L.; Chapman, A.; Bourdeau, I. Characterization of differential gene expression in adrenocortical tumors harboring beta-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E1206–E1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu-Albergine, M.; Tsai, L.C.; Patrucco, E.; Beavo, J.A. cAMP-specific phosphodiesterases 8A and 8B, essential regulators of Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 81, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenbuhler, A.; Horvath, A.; Libé, R.; Faucz, F.R.; Fratticci, A.; Raffin Sanson, M.L.; Vezzosi, D.; Azevedo, M.; Levy, I.; Almeida, M.Q.; et al. Identification of novel genetic variants in phosphodiesterase 8B (PDE8B), a cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase highly expressed in the adrenal cortex, in a cohort of patients with adrenal tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012, 77, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Altieri, B.; Scholz, C.; Sbiera, S.; Luconi, M.; Waldman, J.; Kastelan, D.; Ceccato, F.; Chiodini, I.; Arnaldi, G.; et al. RNA Sequencing and Somatic Mutation Status of Adrenocortical Tumors: Novel Pathogenetic Insights. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e4459–e4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nome, T.; Thomassen, G.O.; Bruun, J.; Ahlquist, T.; Bakken, A.C.; Hoff, A.M.; Rognum, T.; Nesbakken, A.; Lorenz, S.; Sun, J.; et al. Common fusion transcripts identified in colorectal cancer cell lines by high-throughput RNA sequencing. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 6, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, C.M.; Wadell, J.; McLean, K.; Venere, M.; Malik, M.; Shibata, T.; Driggers, P.H.; Kino, T.; Guo, X.C.; Koide, H.; et al. The Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor AKAP13 (BRX) is essential for cardiac development in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 12344–12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot Roussel, H.; Vezzosi, D.; Rizk-Rabin, M.; Barreau, O.; Ragazzon, B.; René-Corail, F.; de Reynies, A.; Bertherat, J.; Assié, G. Identification of gene expression profiles associated with cortisol secretion in adrenocortical adenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E1109–E1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, J.L., 2nd; Zoraghi, R.; Francis, S.H.; Corbin, J.D. N-Terminal domain of phosphodiesterase-11A4 (PDE11A4) decreases affinity of the catalytic site for substrates and tadalafil, and is involved in oligomerization. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 10353–10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.P. A Role for Phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A) in the Formation of Social Memories and the Stabilization of Mood. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 17, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, J.; Hoxie, J.; Liu, C.J.; Cash, M.N.; Luther, J.M.; Gellert, L.; Turcu, A.F.; Else, T.; Giordano, T.J.; Udager, A.M.; et al. Targeted Mutational Analysis of Cortisol-Producing Adenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e594–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemaru, K.I.; Moon, R.T. The transcriptional coactivator CBP interacts with beta-catenin to activate gene expression. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 149, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taurin, S.; Sandbo, N.; Qin, Y.; Browning, D.; Dulin, N.O. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9971–9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Kazi, J.U. Phosphorylation-Dependent Regulation of WNT/Beta-Catenin Signaling. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 858782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drelon, C.; Berthon, A.; Sahut-Barnola, I.; Mathieu, M.; Dumontet, T.; Rodriguez, S.; Batisse-Lignier, M.; Tabbal, H.; Tauveron, I.; Lefrancois-Martinez, A.M.; et al. PKA inhibits WNT signalling in adrenal cortex zonation and prevents malignant tumour development. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissier, F.; Cavard, C.; Groussin, L.; Perlemoine, K.; Fumey, G.; Hagneré, A.M.; René-Corail, F.; Jullian, E.; Gicquel, C.; Bertagna, X.; et al. Mutations of beta-catenin in adrenocortical tumors: Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is a frequent event in both benign and malignant adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 7622–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet-Serrano, F.; Bertherat, J. Genetics of tumors of the adrenal cortex. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2018, 25, R131–R152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanba, K.; Omata, K.; Else, T.; Beck, P.C.C.; Nanba, A.T.; Turcu, A.F.; Miller, B.S.; Giordano, T.J.; Tomlins, S.A.; Rainey, W.E. Targeted Molecular Characterization of Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas in White Americans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3869–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chortis, V.; Kariyawasam, D.; Berber, M.; Guagliardo, N.A.; Leng, S.; Haykir, B.; Ribeiro, C.; Shah, M.S.; Pignatti, E.; Jorgensen, B.; et al. Abrogation of FGFR signaling blocks β-catenin-induced adrenocortical hyperplasia and aldosterone production. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e184863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, L.S.; Carney, J.A.; Pack, S.D.; Taymans, S.E.; Giatzakis, C.; Cho, Y.S.; Cho-Chung, Y.S.; Stratakis, C.A. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A type I-alpha regulatory subunit in patients with the Carney complex. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.Q.; Stratakis, C.A. How does cAMP/protein kinase A signaling lead to tumors in the adrenal cortex and other tissues? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 336, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, C.D.C.; Faucz, F.R.; Voutetakis, A.; Stratakis, C.A. Carney Complex. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 127, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, L.S.; Kusewitt, D.F.; Matyakhina, L.; Towns, W.H., 2nd; Carney, J.A.; Westphal, H.; Stratakis, C.A. A mouse model for the Carney complex tumor syndrome develops neoplasia in cyclic AMP-responsive tissues. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4506–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahut-Barnola, I.; de Joussineau, C.; Val, P.; Lambert-Langlais, S.; Damon, C.; Lefrançois-Martinez, A.-M.; Pointud, J.-C.; Marceau, G.; Sapin, V.; Tissier, F.; et al. Cushing’s Syndrome and Fetal Features Resurgence in Adrenal Cortex–Specific Prkar1a Knockout Mice. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, A.; Bertherat, J. Update of Genetic and Molecular Causes of Adrenocortical Hyperplasias Causing Cushing Syndrome. Horm. Metab. Res. 2020, 52, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drougat, L.; Settas, N.; Ronchi, C.L.; Bathon, K.; Calebiro, D.; Maria, A.G.; Haydar, S.; Voutetakis, A.; London, E.; Faucz, F.R.; et al. Genomic and sequence variants of protein kinase A regulatory subunit type 1β (PRKAR1B) in patients with adrenocortical disease and Cushing syndrome. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, G.; Lania, A.G.; Bondioni, S.; Peverelli, E.; Pedroni, C.; Ferrero, S.; Pellegrini, C.; Vicentini, L.; Arnaldi, G.; Bosari, S.; et al. Different expression of protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunits in cortisol-secreting adrenocortical tumors: Relationship with cell proliferation. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, I.; Ronchi, C.L.; Rizk-Rabin, M.; Dalmazi, G.D.; Wild, V.; Bathon, K.; Rubin, B.; Calebiro, D.; Beuschlein, F.; Bertherat, J.; et al. Differential expression of the protein kinase A subunits in normal adrenal glands and adrenocortical adenomas. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, I.; Ronchi, C.L.; Vanselow, J.T.; Bathon, K.; Lenz, K.; Herterich, S.; Schlosser, A.; Kroiss, M.; Fassnacht, M.; Calebiro, D.; et al. PKA Cα subunit mutation triggers caspase-dependent RIIβ subunit degradation via Ser(114) phosphorylation. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuschlein, F.; Fassnacht, M.; Assie, G.; Calebiro, D.; Stratakis, C.A.; Osswald, A.; Ronchi, C.L.; Wieland, T.; Sbiera, S.; Faucz, F.R.; et al. Constitutive activation of PKA catalytic subunit in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, M.; Gao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Zhong, X.; Lei, Y.; et al. Activating hotspot L205R mutation in PRKACA and adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Science 2014, 344, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.; Scholl, U.I.; Healy, J.M.; Choi, M.; Prasad, M.L.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Kunstman, J.W.; Korah, R.; Suttorp, A.C.; Dietrich, D.; et al. Recurrent activating mutation in PRKACA in cortisol-producing adrenal tumors. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Kisker, C.; Calebiro, D.; Mannelli, M.; Canu, L.; Arnaldi, G.; Quinkler, M.; Rayes, N.; Tabarin, A.; Laure Jullie, M.; et al. Novel somatic mutations in the catalytic subunit of the protein kinase A as a cause of adrenal Cushing’s syndrome: A European multicentric study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2093–E2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, B.; Tang, L.; Lang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, J.; Zhang, X. Clinical characteristics of PRKACA mutations in Chinese patients with adrenal lesions: A single-centre study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 85, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, C.L.; Di Dalmazi, G.; Faillot, S.; Sbiera, S.; Assié, G.; Weigand, I.; Calebiro, D.; Schwarzmayr, T.; Appenzeller, S.; Rubin, B.; et al. Genetic Landscape of Sporadic Unilateral Adrenocortical Adenomas Without PRKACA p.Leu206Arg Mutation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3526–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espiard, S.; Knape, M.J.; Bathon, K.; Assié, G.; Rizk-Rabin, M.; Faillot, S.; Luscap-Rondof, W.; Abid, D.; Guignat, L.; Calebiro, D.; et al. Activating PRKACB somatic mutation in cortisol-producing adenomas. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.H. Disruptions to protein kinase A localization in adrenal pathology. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2024, 52, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.H.; Kihiu, M.; Byrne, D.P.; Lee, K.S.; Lakey, T.M.; Butcher, E.; Eyers, P.A.; Scott, J.D. Classification of Cushing’s syndrome PKAc mutants based upon their ability to bind PKI. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.H.; Byrne, D.P.; Jones, K.N.; Lakey, T.M.; Collins, K.B.; Lee, K.-S.; Daly, L.A.; Forbush, K.A.; Lau, H.-T.; Golkowski, M.; et al. Mislocalization of protein kinase A drives pathology in Cushing’s syndrome. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.H.; Byrne, D.P.; Shrestha, S.; Lakey, T.M.; Lee, K.-S.; Lauer, S.M.; Collins, K.B.; Daly, L.A.; Eyers, C.E.; Baird, G.S.; et al. Discovery of a Cushing’s syndrome protein kinase A mutant that biases signaling through type I AKAPs. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.; Wang, Y.; Olivieri, C.; Karamafrooz, A.; Casby, J.; Bathon, K.; Calebiro, D.; Gao, J.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Taylor, S.S.; et al. Cushing’s syndrome driver mutation disrupts protein kinase A allosteric network, altering both regulation and substrate specificity. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.; Wang, Y.; Olivieri, C.; VS, M.; Gao, J.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Calebiro, D.; Taylor, S.S.; Veglia, G. Is Disrupted Nucleotide-Substrate Cooperativity a Common Trait for Cushing’s Syndrome Driving Mutations of Protein Kinase A? J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calebiro, D.; Hannawacker, A.; Lyga, S.; Bathon, K.; Zabel, U.; Ronchi, C.; Beuschlein, F.; Reincke, M.; Lorenz, K.; Allolio, B.; et al. PKA catalytic subunit mutations in adrenocortical Cushing’s adenoma impair association with the regulatory subunit. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-R.; Sang, L.; Yue, D.T. Uncovering Aberrant Mutant PKA Function with Flow Cytometric FRET. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 3019–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzi, N.M.; Lyons, C.E.; Peterson, D.L.; Ellis, K.C. Kinetics and inhibition studies of the L205R mutant of cAMP-dependent protein kinase involved in Cushing’s syndrome. FEBS Open Bio 2018, 8, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, S.A.; McKnight, G.S. Mutations in the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase result in unregulated biological activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 4726–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, S.A.; Amieux, P.S.; Zhao, X.; McKnight, G.S. Mutations in the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase interfere with holoenzyme formation without disrupting inhibition by protein kinase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 6843–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Yaron, T.M.; Huntsman, E.M.; Kerelsky, A.; Song, J.; Regev, A.; Lin, T.-Y.; Liberatore, K.; Cizin, D.M.; Cohen, B.M.; et al. An atlas of substrate specificities for the human serine/threonine kinome. Nature 2023, 613, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleymani, S.; Gravel, N.; Huang, L.-C.; Yeung, W.; Bozorgi, E.; Bendzunas, N.G.; Kochut, K.J.; Kannan, N. Dark kinase annotation, mining, and visualization using the Protein Kinase Ontology. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubner, J.M.; Dodge-Kafka, K.L.; Carlson, C.R.; Church, G.M.; Chou, M.F.; Schwartz, D. Cushing’s syndrome mutant PKA(L)(205R) exhibits altered substrate specificity. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathon, K.; Weigand, I.; Vanselow, J.T.; Ronchi, C.L.; Sbiera, S.; Schlosser, A.; Fassnacht, M.; Calebiro, D. Alterations in Protein Kinase A Substrate Specificity as a Potential Cause of Cushing Syndrome. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.S.; Hsu, P.H.; Lo, P.W.; Scheer, E.; Tora, L.; Tsai, H.J.; Tsai, M.D.; Juan, L.J. Protein kinase A-mediated serine 35 phosphorylation dissociates histone H1.4 from mitotic chromosome. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 35843–35851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroishi, T.; Hansen, C.G.; Guan, K.L. The emerging roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Hansen, C.G. The Hippo pathway in cancer: YAP/TAZ and TEAD as therapeutic targets in cancer. Clin. Sci. 2022, 136, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, J.; Sczaniecka, A.; Heidary Arash, E.; Nguyen, L.; Chen, C.C.; Ratkovic, S.; Klezovitch, O.; Attisano, L.; McNeill, H.; Emili, A.; et al. DLG5 connects cell polarity and Hippo signaling protein networks by linking PAR-1 with MST1/2. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, M.; Huang, L.; Ma, Z.; Gong, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, W.; et al. ERK1 indicates good prognosis and inhibits breast cancer progression by suppressing YAP1 signaling. Aging 2019, 11, 12295–12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonga, O.E.; Enkvist, E.; Herberg, F.W.; Uri, A. Inhibitors and fluorescent probes for protein kinase PKAcβ and its S54L mutant, identified in a patient with cortisol producing adenoma. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Z.; Cheng, X. Origin and Isoform Specific Functions of Exchange Proteins Directly Activated by cAMP: A Phylogenetic Analysis. Cells 2021, 10, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.E.; Aesoy, R.; Bakke, M. Role of EPAC in cAMP-Mediated Actions in Adrenocortical Cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumo, L.; Rusten, M.; Mellgren, G.; Bakke, M.; Lewis, A.E. Functional roles of protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein directly activated by 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5’-monophosphate (cAMP) 2 (EPAC2) in cAMP-mediated actions in adrenocortical cells. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Oliveira Barbosa, E.; Roggero, E.A.; González, F.B.; Fernández, R.D.V.; Carvalho, V.F.; Bottasso, O.A.; Pérez, A.R.; Villar, S.R. Evidence in Favor of an Alternative Glucocorticoid Synthesis Pathway During Acute Experimental Chagas Disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000143630-HCN3/tissue/adrenal+gland (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Brand, T.; Schindler, R. New kids on the block: The Popeye domain containing (POPDC) protein family acting as a novel class of cAMP effector proteins in striated muscle. Cell. Signal. 2017, 40, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Omar, M.H. Protein Kinase A Signaling in Cortisol Production and Adrenal Cushing’s Syndrome. Cells 2026, 15, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010063

Kumar A, Sharma A, Omar MH. Protein Kinase A Signaling in Cortisol Production and Adrenal Cushing’s Syndrome. Cells. 2026; 15(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Abhishek, Abhimanyu Sharma, and Mitchell H. Omar. 2026. "Protein Kinase A Signaling in Cortisol Production and Adrenal Cushing’s Syndrome" Cells 15, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010063

APA StyleKumar, A., Sharma, A., & Omar, M. H. (2026). Protein Kinase A Signaling in Cortisol Production and Adrenal Cushing’s Syndrome. Cells, 15(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010063