Dissecting the Biological Functions of Various Isoforms of Ferredoxin Reductase for Cell Survival and DNA Damage Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture and Cell Line Generation

2.3. RNA Interference (RNAi)

2.4. Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Phase-Contrast Microscopy

2.5. Western Blotting Analysis

2.6. Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

2.8. Colony Formation Assay

2.9. Recombinant Protein Expression

2.10. Cell Viability Assay

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Expression Profiles of Various FDXR Isoforms

3.2. All Seven FDXR Isoforms Are Induced by DNA Damage in a p53-Dependent Manner

3.3. Generation and Validation of Isoform-Specific FDXR Knockout Cell Lines

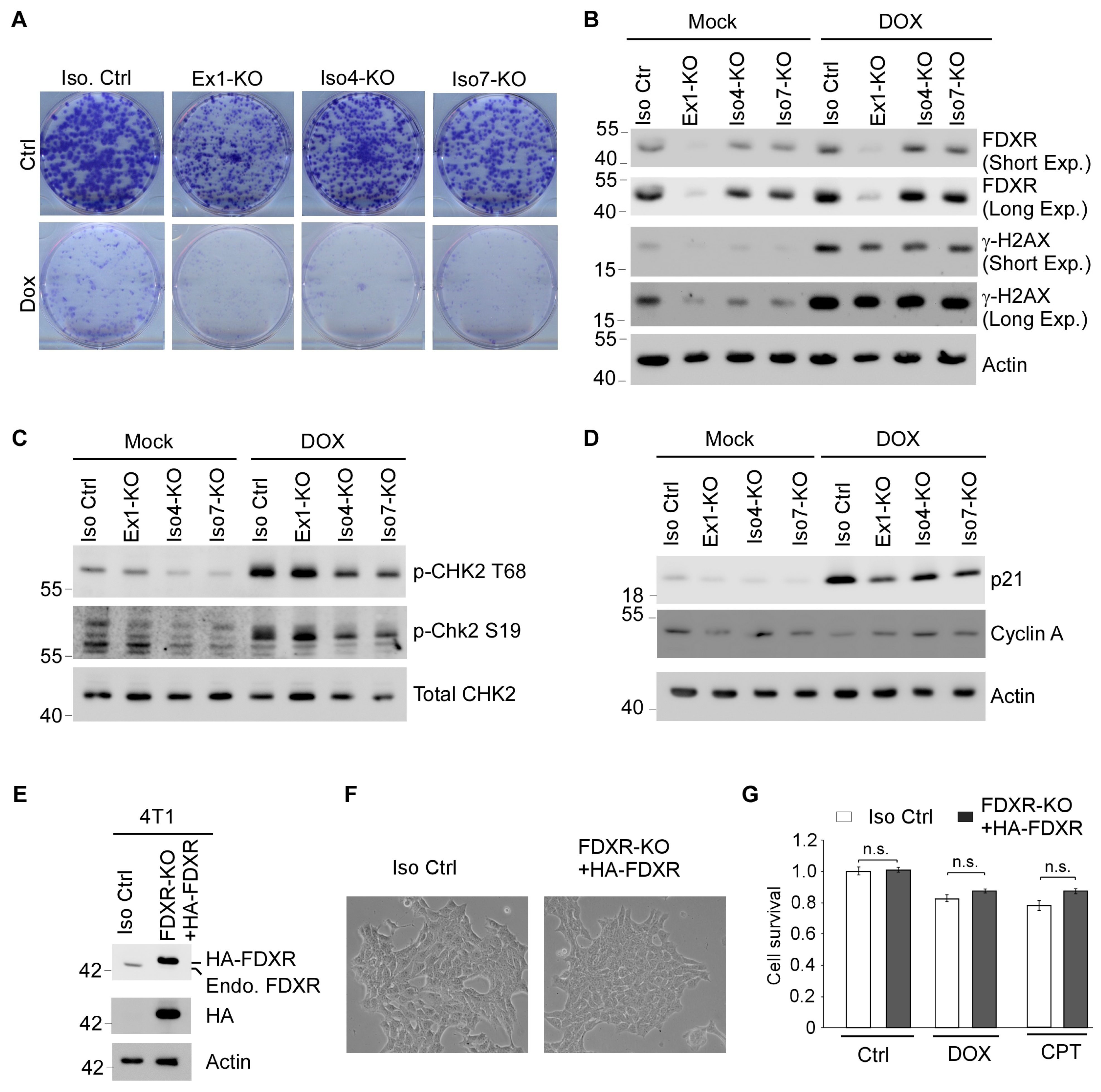

3.4. Each FDXR Isoform Contributes to Cell Viability

3.5. Cells Deficient in One or More FDXR Isoforms Are Prone to DNA Damage-Induced Growth Suppression Along with Impaired DNA Damage Response

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suhara, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Takemori, S.; Katagiri, M. The purification and properties of NADPH-adrenodoxin reductase from bovine adrenocortical mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1972, 28, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L. Steroidogenic electron-transfer factors and their diseases. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 26, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Adinolfi, S.; Pastore, A. Ferredoxin, in conjunction with NADPH and ferredoxin-NADP reductase, transfers electrons to the IscS/IscU complex to promote iron-sulfur cluster assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Proteins Proteom. 2015, 1854, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, V.; Freibert, S.A.; Boss, L.; Muhlenhoff, U.; Stehling, O.; Lill, R. Mitochondrial [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins: New functions for old dogs. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheftel, A.D.; Stehling, O.; Pierik, A.J.; Elsasser, H.P.; Muhlenhoff, U.; Webert, H.; Hobler, A.; Hannemann, F.; Bernhardt, R.; Lill, R. Humans possess two mitochondrial ferredoxins, Fdx1 and Fdx2, with distinct roles in steroidogenesis, heme, and Fe/S cluster biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11775–11780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, K.M.; Hannemann, F.; Iametti, S.; Morleo, A.; Bernhardt, R. Functional characterization of Fdx1: Evidence for an evolutionary relationship between P450-type and ISC-type ferredoxins. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 413, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Tonelli, M.; Frederick, R.O.; Markley, J.L. Human Mitochondrial Ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) and Ferredoxin 2 (FDX2) Both Bind Cysteine Desulfurase and Donate Electrons for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhilper, R.; Boss, L.; Freibert, S.A.; Schulz, V.; Krapoth, N.; Kaltwasser, S.; Lill, R.; Murphy, B.J. Two-stage binding of mitochondrial ferredoxin-2 to the core iron-sulfur cluster assembly complex. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Drecourt, A.; Petit, F.; Deguine, D.D.; Vasnier, C.; Oufadem, M.; Masson, C.; Bonnet, C.; Masmoudi, S.; Mosnier, I.; et al. FDXR Mutations Cause Sensorial Neuropathies and Expand the Spectrum of Mitochondrial Fe-S-Synthesis Diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, J.; Peng, Y.; Chamberlin, A.; Harris, B.; Kaylor, J.; McDonald, M.T.; Lemmon, M.; El-Dairi, M.A.; Tchapyjnikov, D.; Gonzalez-Krellwitz, L.A.; et al. Biallelic mutations in FDXR cause neurodegeneration associated with inflammation. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 63, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, G.S.; Chinnery, P.F.; DiMauro, S.; Hirano, M.; Koga, Y.; McFarland, R.; Suomalainen, A.; Thorburn, D.R.; Zeviani, M.; Turnbull, D.M. Mitochondrial diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slone, J.D.; Yang, L.; Peng, Y.; Queme, L.F.; Harris, B.; Rizzo, S.J.S.; Green, T.; Ryan, J.L.; Jankowski, M.P.; Reinholdt, L.G.; et al. Integrated analysis of the molecular pathogenesis of FDXR-associated disease. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Shinde, D.N.; Valencia, C.A.; Mo, J.S.; Rosenfeld, J.; Truitt Cho, M.; Chamberlin, A.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Gui, B.; et al. Biallelic mutations in the ferredoxin reductase gene cause novel mitochondriopathy with optic atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4937–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignatti, E.; Slone, J.; Gomez Cano, M.A.; Campbell, T.M.; Vu, J.; Sauter, K.S.; Pandey, A.V.; Martinez-Azorin, F.; Alonso-Riano, M.; Neilson, D.E.; et al. FDXR variants cause adrenal insufficiency and atypical sexual development. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e179071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, W.; Jung, Y.S.; Chen, M.; Huang, E.; Lloyd, K.; Duan, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Ferredoxin reductase is critical for p53-dependent tumor suppression via iron regulatory protein 2. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mohibi, S.; Vasilatis, D.M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Ferredoxin reductase and p53 are necessary for lipid homeostasis and tumor suppression through the ABCA1-SREBP pathway. Oncogene 2022, 41, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montealegre, S.; Lebigot, E.; Debruge, H.; Romero, N.; Heron, B.; Gaignard, P.; Legendre, A.; Imbard, A.; Gobin, S.; Lacene, E.; et al. FDX2 and ISCU Gene Variations Lead to Rhabdomyolysis With Distinct Severity and Iron Regulation. Neurol. Genet. 2022, 8, e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiourtzis, N.; Tramma, D.; Papadopoulou-Legbelou, K.; Moutafi, M.; Evangeliou, A. Alpha rare case of myopathy, lactic acidosis, and severe rhabdomyolysis, due to a homozygous mutation of the ferredoxin-2 (FDX2) gene. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2023, 191, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkittichote, P.; Pantano, C.; He, M.; Hong, X.; Demczko, M.M. Clinical, biochemical and molecular characterization of a new case with FDX2-related mitochondrial disorder: Potential biomarkers and treatment options. JIMD Rep. 2024, 65, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoska, K.; Abend, M.; O’Brien, G.; Gregoire, E.; Port, M.; Badie, C. Calibration curve for radiation dose estimation using FDXR gene expression biodosimetry-premises and pitfalls. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2024, 100, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, O.; White, L.; Cullen, D.; O’Brien, G.; Shields, L.; Bryant, J.; Noone, E.; Bradshaw, S.; Finn, M.; Dunne, M.; et al. A 4-Gene Signature of CDKN1, FDXR, SESN1 and PCNA Radiation Biomarkers for Prediction of Patient Radiosensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Garcia, L.; O’Brien, G.; Sipos, B.; Mayes, S.; Tichy, A.; Sirak, I.; Davidkova, M.; Markova, M.; Turner, D.J.; Badie, C. In Vivo Validation of Alternative FDXR Transcripts in Human Blood in Response to Ionizing Radiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, G.; Cruz-Garcia, L.; Majewski, M.; Grepl, J.; Abend, M.; Port, M.; Tichy, A.; Sirak, I.; Malkova, A.; Donovan, E.; et al. FDXR is a biomarker of radiation exposure in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Chen, X. The ferredoxin reductase gene is regulated by the p53 family and sensitizes cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 2002, 21, 7195–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.M.; Bunz, F.; Yu, J.; Rago, C.; Chan, T.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Kelso, G.F.; Smith, R.A.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Ferredoxin reductase affects p53-dependent, 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druck, T.; Cheung, D.G.; Park, D.; Trapasso, F.; Pichiorri, F.; Gaspari, M.; Palumbo, T.; Aqeilan, R.I.; Gaudio, E.; Okumura, H.; et al. Fhit-Fdxr interaction in the mitochondria: Modulation of reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis in cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.R.; Dobritsa, A.; Gaines, P.; Segraves, W.A.; Carlson, J.R. The dare gene: Steroid hormone production, olfactory behavior, and neural degeneration in Drosophila. Development 1999, 126, 4591–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solish, S.B.; Picado-Leonard, J.; Morel, Y.; Kuhn, R.W.; Mohandas, T.K.; Hanukoglu, I.; Miller, W.L. Human adrenodoxin reductase: Two mRNAs encoded by a single gene on chromosome 17cen----q25 are expressed in steroidogenic tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 7104–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, B.L.; Vickery, L.E. Expression of Human Ferredoxin in Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae-Mitochondrial Import of the Protein and Assembly of the [2fe-2s] Center. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 294, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, V.M.; Vickery, L.E. Expression of Human Ferredoxin and Assembly of the [2fe-2s] Center in Escherichia-Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Tanaka-Nozaki, M.; Kato, S.; Blomeke, B. Influence of 5-fluorouracil on ferredoxin reductase mRNA splice variants in colorectal carcinomas. Oncol. Lett. 2010, 1, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchesi, C.A.; Zhang, J.; Ma, B.; Chen, M.; Chen, X. Disruption of the Rbm38-eIF4E Complex with a Synthetic Peptide Pep8 Increases p53 Expression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohn, M.; Nozell, S.; Willis, A.; Chen, X. Tumor suppressor gene-inducible cell lines. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003, 223, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, B.; Chen, X. DEC1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and a novel target gene of the p53 family, mediates p53-dependent premature senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 2896–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.F. DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989, 58, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, S.; Koshlatyi, S.; Lu, T.; Gopen, T.; Bargonetti, J. Camptothecin and Zeocin can increase p53 levels during all cell cycle stages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 289, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Yan, W.; Chen, X. RNPC1, an RNA-binding protein and a target of the p53 family, is required for maintaining the stability of the basal and stress-induced p21 transcript. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2961–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, L.J.; El-Osta, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. gammaH2AX: A sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 2010, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, L.; Delia, D.; Buscemi, G. CHK2 kinase in the DNA damage response and beyond. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 6, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, D.; Li, Z.; Xu, R.; Cheng, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; You, C. Uncover DNA damage and repair-related gene signature and risk score model for glioma. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2200033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zou, B.J.; Zhao, J.Z.; Liang, J.B.; She, Z.Y.; Zhou, W.Y.; Lin, S.X.; Tian, L.; Luo, W.J.; He, F.Z. A novel DNA damage repair-related signature for predicting prognositc and treatment response in non-small lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 961274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, D.S.; Pena-Chilet, M.; Cordero Varela, J.A.; Alvarez-Alegret, R.; Agra-Pujol, C.; Izquierdo, F.; Ramos, R.; Ortega-Medina, L.; Martin-Davila, F.; Castilla-Ramirez, C.; et al. A DNA damage repair gene-associated signature predicts responses of patients with advanced soft-tissue sarcoma to treatment with trabectedin. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 3691–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Wu, S.; Zhao, X.; Jing, J. A Novel DNA Damage Repair-Related Gene Signature for Predicting Glioma Prognosis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 10083–10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Ahmad, R.; Tantry, I.Q.; Ahmad, W.; Siddiqui, S.; Alam, M.; Abbas, K.; Moinuddin; Hassan, M.I.; Habib, S.; et al. Apoptosis: A Comprehensive Overview of Signaling Pathways, Morphological Changes, and Physiological Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2024, 13, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, M.; Reme, T.; Goldschmidt, H.; Fiol, G.; Pantesco, V.; De Vos, J.; Rossi, J.F.; Hose, D.; Klein, B. Gene expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic proteins in malignant and normal plasma cells. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 145, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.Y.; Zhao, W.J.; Xiao, S.G.; Lu, Y.X. A Signature of Three Apoptosis-Related Genes Predicts Overall Survival in Breast Cancer. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 863035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinew, G.M.; Messeha, S.; Taka, E.; Ahmed, S.A.; Soliman, K.F.A. The Role of Apoptotic Genes and Protein-Protein Interactions in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2023, 20, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Exon 1 sgRNA #1 | Forward: 5′-caccgCGGGATTCTCTCGGGAGTCG-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacCGACTCCCGAGAGAATCCCGc-3′ |

| Exon 1 sgRNA #2 | Forward: 5′-caccgCGAGATCCCGGTGGTGTAC-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacGTACACCACCGGGATCTCGCc-3′ |

| Isoform 4 sgRNA #1 | Forward: 5′-caccgACTTCATCTGAACCCCCAA-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacTTGGGGGTTCAGATGAAGTc-3′ |

| Isoform 4 sgRNA #2 | Forward: 5′-caccgTCAAGGCTTTGGCATTTGCA-3′ Reverse: 5′ -aaacTGCAAATGCCAAAGCCTTGAc-3′ |

| Isoform 7 sgRNA #1 | Forward: 5′-caccgGTTCAAACTGCTCGGCCTAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacCTAGGCCGAGCAGTTTGAACc-3′ |

| Isoform 7 sgRNA #2 | Forward: 5′-caccgACATCCAAGGGTCTCAGGTT-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacAACCTGAGACCCTTGGATGTc-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Exon 1-KO genotyping | Forward: 5′-GCGTATACCCCGGATGCTC-3′ Reverse: 5′-TCACCTTTGTTGACCTCCGTC-3′ |

| Isoform 4-KO genotyping | Forward: 5′-CCGTTGGAAGGATGTGGGAT-3′ Reverse: 5′-CCAGTCCCAAACCAACCTGA-3′ |

| Isoform 7-KO genotyping | Forward: 5′-CGAGGGAACAGGAGCAGAAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-GCCTTGCTCAAAAATCTTCGC-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Exon 3 sgRNA #1 | Forward: 5′-caccgCTTCTCGTAGATGTCTACGT-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacACGTAGACATCTACGAGAAGc-3′ |

| Exon 3 sgRNA #2 | Forward: 5′-caccgCCAACACCACCCTCCGCACC-3′ Reverse: 5′-aaacGGTGCGGAGGGTGGTGTTGGc-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Scrambled siRNA | 5′-GCAGUGUCUCCACGCACUAdTdT-3′ |

| siFDXR #1 | 5′-GCUCAGCAGCAUUGGGUAUUU-3′ |

| siFDXR #2 | 5′-CACCAUUAAGGAGCUUCGG-3′ |

| siIso7 | 5′-AGGAAAGAAUGGAAGAUAAUU-3′ |

| siEx2 | 5′-CGGCCCAACACCUGCUAAAdTdT-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| FDXR (Total) | Forward: 5′-GTACAACGGGCTTCCTGAGA-3′ Reverse: 5′-CTCAGGTGGGGTCAGTAGGA-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#2) | Forward: 5′-CTGAGAACCAGGAGCTGGAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-GTCCGTTCTCTGGCACAAA-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#3) | Forward: 5′-GGTGGAAGCCTTGTGTTCT-3′ Reverse: 5′-GAGAGAGAGAGGCTGGGA-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#4) | Forward: 5′-TGAAGTAAGAGACCCTGCAAAT-3′ Reverse: 5′-ATATCCAACAGAAGCTGGAACT-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#5) | Forward: 5′-CTTCTACACGGCCCAACAC-3′ Reverse: 5′-AATGGGCCGTCTTCACCT-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#6) | Forward: 5′-GCCACCATTTCTCCACACAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-CCCCGTAGCTCTTCACCTC-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#7) | Forward: 5′-AGGTCAGCCACGAGAGATA-3′ Reverse: 5′-GCTCTCTGTCCTTATCTTCCATTC-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| FDXR (Total) | Forward: 5′-GTACAACGGGCTTCCTGAGA-3′ Reverse: 5′-CTCAGGTGGGGTCAGTAGGA-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#1) | Forward: 5′-GCAGTAGCTAGGAACAGATCC-3′ Reverse: 5′-TGTGTGGAGAAATGGTGGCAG-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#4) | Forward: 5′-GCTTCGCGCTGCTGGCGCTG-3′ Reverse: 5′-ATATCCAACAGAAGCTGGAACT-3′ |

| FDXR (Iso#7) | Forward: 5′-AGGTCAGCCACGAGAGATA-3′ Reverse: 5′-GCTCTCTGTCCTTATCTTCCATTC-3′ |

| Actin | Forward: 5′-CACTGTGCCCATCTACGAGG-3′ Reverse: 5′-TGGCCATCTCTTGCTCGAAG-3′ |

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| p53RE #1 | Forward: 5′-CCTCATGACAACCTGCAAAGC-3′ Reverse: 5′-TGTTCCCAGTAAAGCCTGCG-3′ |

| p53RE #2 | Forward: 5′-TGTCCCAGGCACAGAGAACT-3′ Reverse: 5′-TCTGATCGGGGAAGAGGAGG-3′ |

| p21 | Forward: 5′-CAGGCTGTGGCTCTGATTGG-3′ Reverse: 5′-TTCAGAGTAACAGGCTAAGG-3′ |

| GAPDH | Forward: 5′-AAAAGCGGGGAGAAAGTAGG-3′ Reverse: 5′-AAGAAGATGCGGCTGACTGT-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakajima, K.-i.; Mohibi, S.; Hong, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J. Dissecting the Biological Functions of Various Isoforms of Ferredoxin Reductase for Cell Survival and DNA Damage Response. Cells 2026, 15, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010062

Nakajima K-i, Mohibi S, Hong K, Chen X, Zhang J. Dissecting the Biological Functions of Various Isoforms of Ferredoxin Reductase for Cell Survival and DNA Damage Response. Cells. 2026; 15(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakajima, Ken-ichi, Shakur Mohibi, Kyle Hong, Xinbin Chen, and Jin Zhang. 2026. "Dissecting the Biological Functions of Various Isoforms of Ferredoxin Reductase for Cell Survival and DNA Damage Response" Cells 15, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010062

APA StyleNakajima, K.-i., Mohibi, S., Hong, K., Chen, X., & Zhang, J. (2026). Dissecting the Biological Functions of Various Isoforms of Ferredoxin Reductase for Cell Survival and DNA Damage Response. Cells, 15(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010062