Genetic Modeling of Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) in the Brain–Midgut Axis of Drosophila melanogaster During Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ortholog Prediction and Definition of DIOPT Score and Homology Ranking

2.2. Structural Alignment

2.3. Drosophila melanogaster Strain Stocks and Culturing Conditions

2.4. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

2.5. Longevity Measurement

2.6. Negative Geotaxis Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. From Humans to Flies: Identification of LSD-Related Gene Orthologs Using the DIOPT

3.2. Structural Conservation of LSD-Associated Proteins Between Homo Sapiens and Drosophila melanogaster

3.3. Modeling of Sphingolipidoses in Drosophila

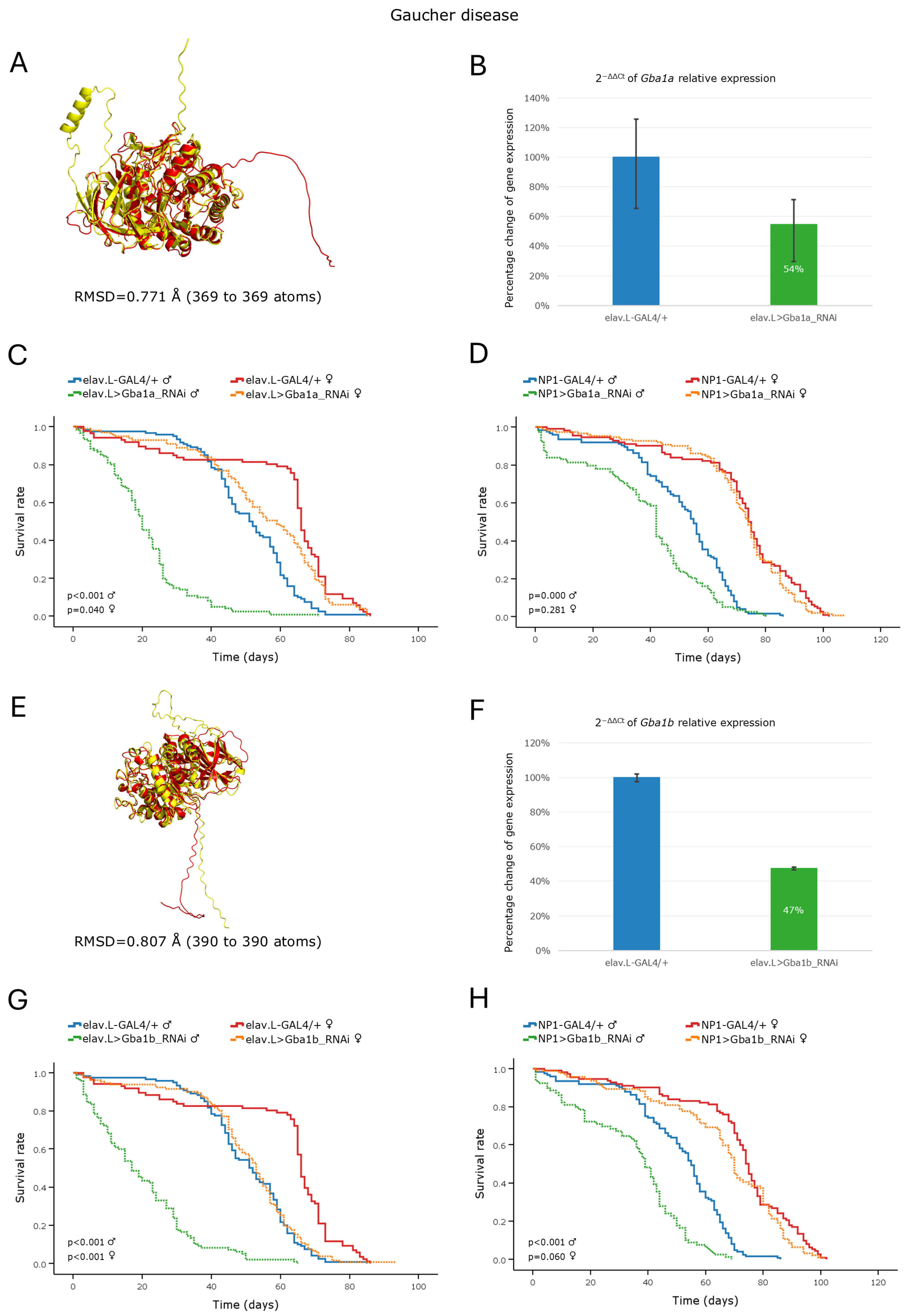

3.3.1. Gaucher Disease

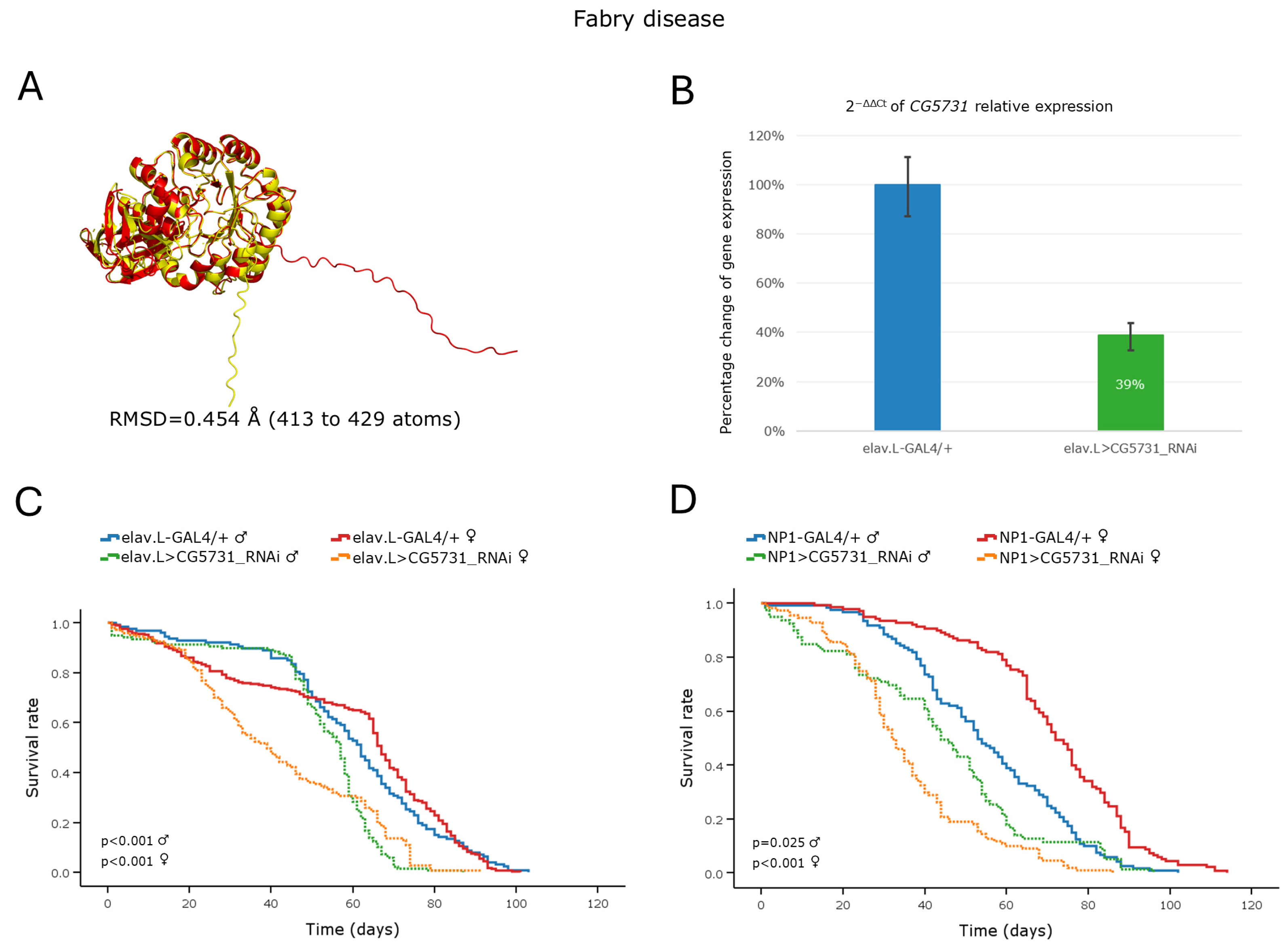

3.3.2. Fabry Disease

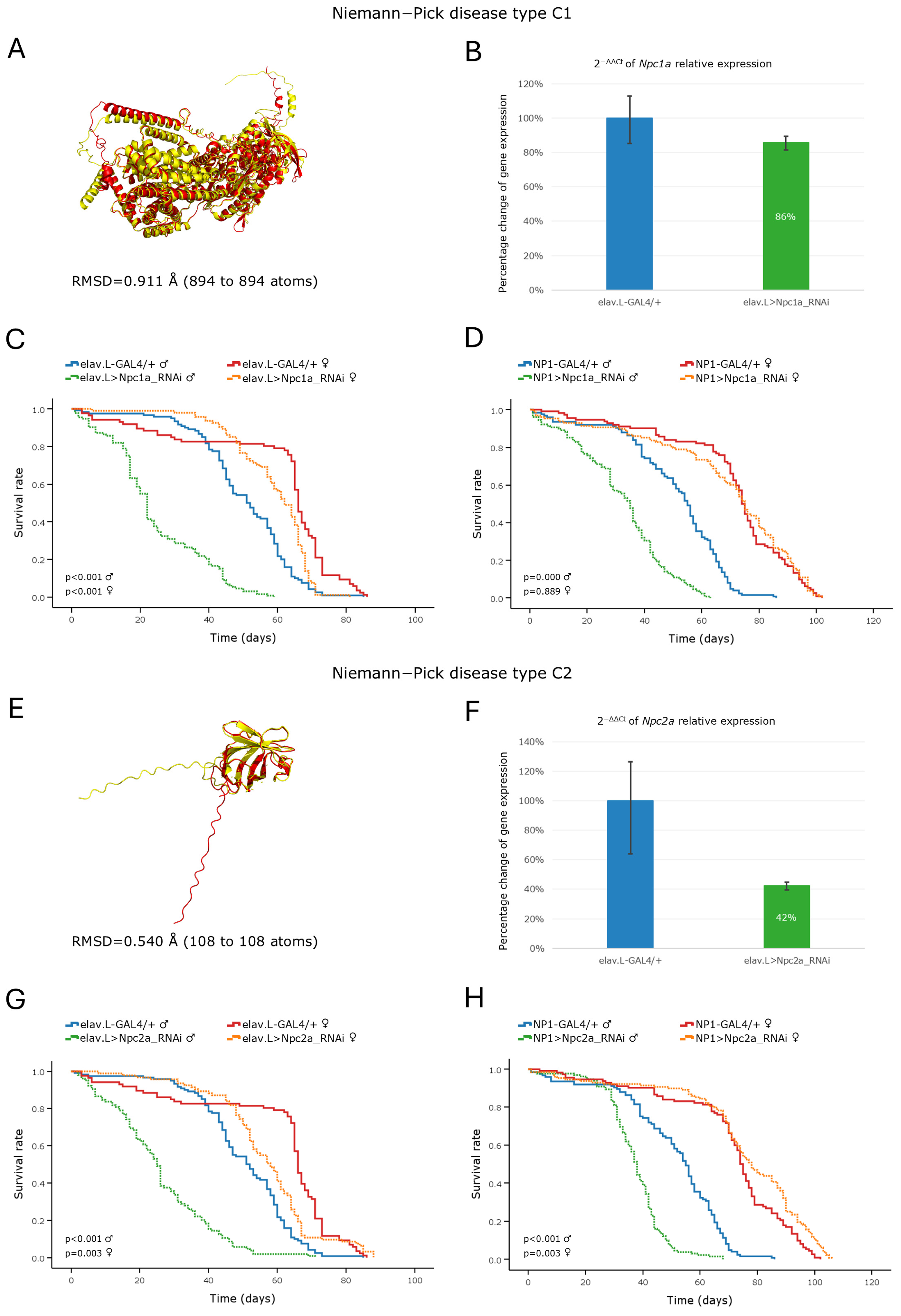

3.3.3. Niemann–Pick Disease

3.3.4. Tay–Sachs/Sandhoff Disease(s)

3.4. Modeling of Pompe Disease in Drosophila

Pompe Disease

3.5. Modeling of Mucopolysaccharidoses in Drosophila

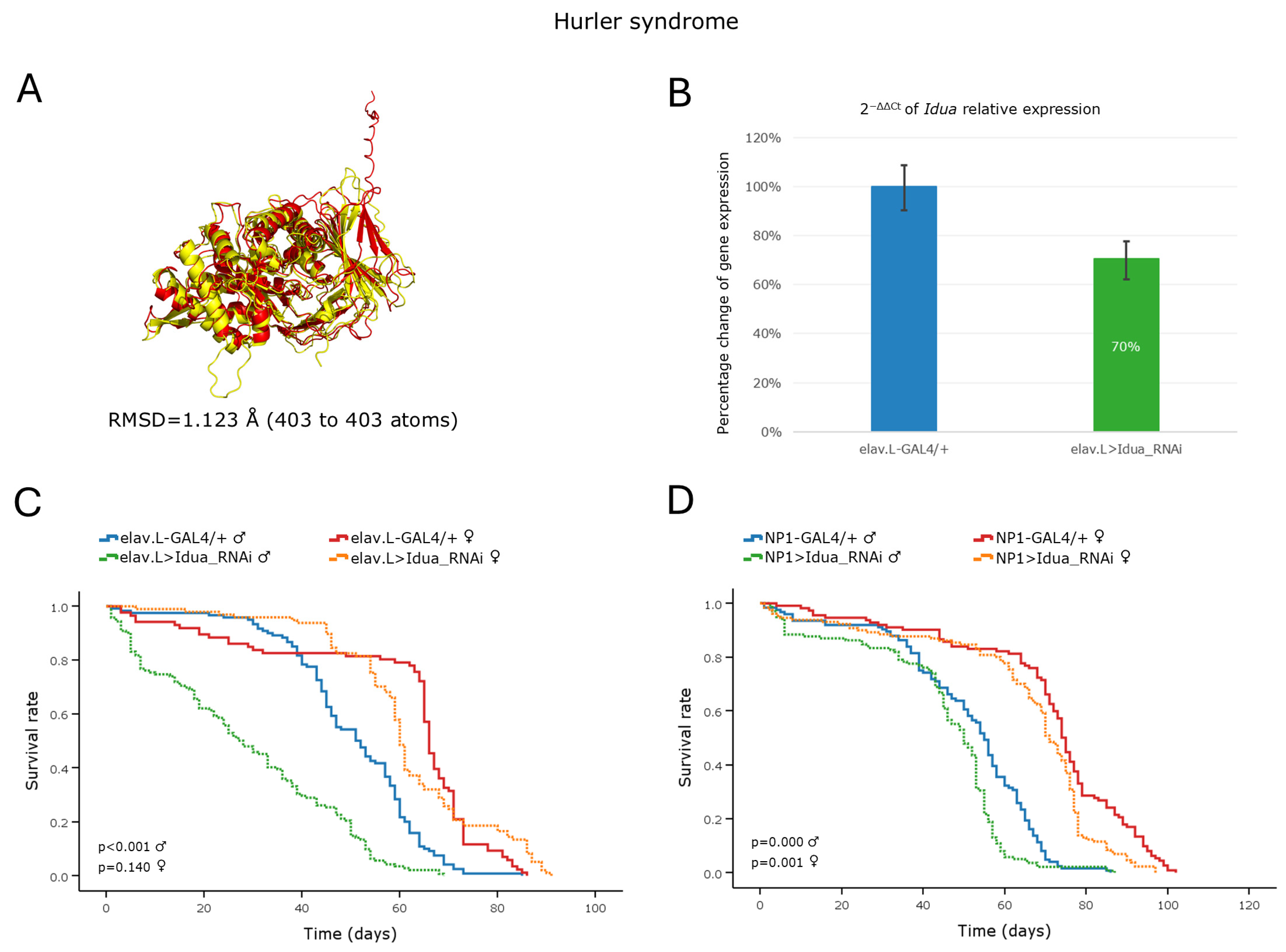

3.5.1. Hurler Syndrome

3.5.2. Hunter Syndrome

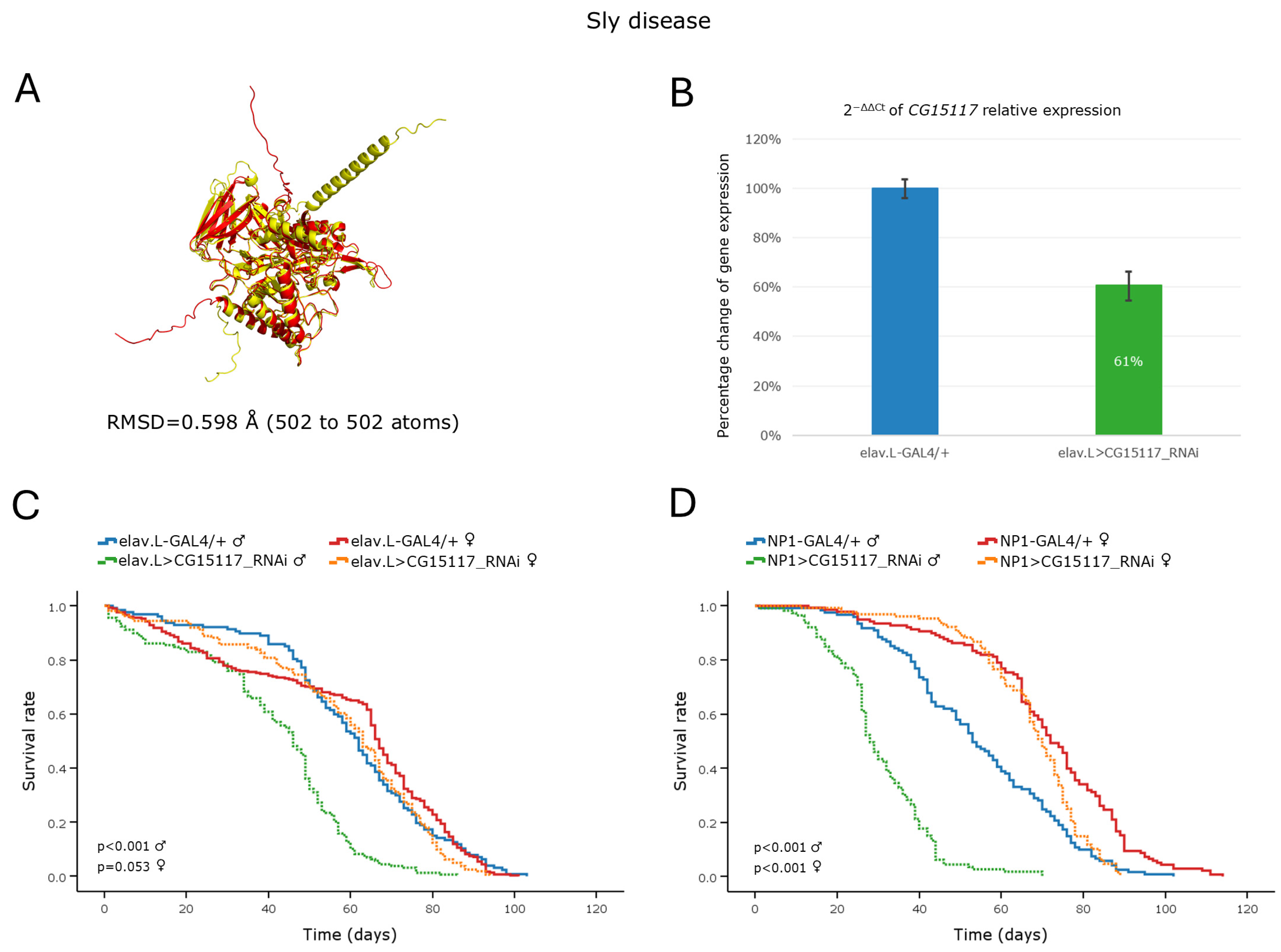

3.5.3. Sly Disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parenti, G.; Andria, G.; Ballabio, A. Lysosomal storage diseases: From pathophysiology to therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.; Meikle, P.J.; Hopwood, J.J. Epidemiology of lysosomal storage diseases: An overview. In Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS; Mehta, A., Beck, M., Sunder-Plassmann, G., Eds.; Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meikle, P.J.; Hopwood, J.J.; Clague, A.E.; Carey, W.F. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA 1999, 281, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, F.M.; d’Azzo, A.; Davidson, B.L.; Neufeld, E.F.; Tifft, C.J. Lysosomal storage diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seranova, E.; Connolly, K.J.; Zatyka, M.; Rosenstock, T.R.; Barrett, T.; Tuxworth, R.I.; Sarkar, S. Dysregulation of autophagy as a common mechanism in lysosomal storage diseases. Essays Biochem. 2017, 61, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gool, R.; Tucker-Bartley, A.; Yang, E.; Todd, N.; Guenther, F.; Goodlett, B.; Al-Hertani, W.; Bodamer, O.A.; Upadhyay, J. Targeting neurological abnormalities in lysosomal storage diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.R.A.; Saftig, P. Lysosomal storage disorders—Challenges, concepts and avenues for therapy: Beyond rare diseases. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs221739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson-Lawrence, E.J.; Shandala, T.; Prodoehl, M.; Plew, R.; Borlace, G.N.; Brooks, D.A. Lysosomal storage disease: Revealing lysosomal function and physiology. Physiology 2010, 25, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkara, H.A. Recent advances in the biochemistry and genetics of sphingolipidoses. Brain Dev. 2004, 26, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolter, T.; Sandhoff, K. Sphingolipid metabolism diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 2057–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerowitz, R. Tay-Sachs disease-causing mutations and neutral polymorphisms in the Hex A gene. Hum. Mutat. 1997, 9, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrieger, F.W. The Niemann-Pick type diseases—A synopsis of inborn errors in sphingolipid and cholesterol metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 2023, 90, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubaski, F.; de Oliveira Poswar, F.; Michelin-Tirelli, K.; Matte, U.D.S.; Horovitz, D.D.; Barth, A.L.; Baldo, G.; Vairo, F.; Giugliani, R. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, T.; Feltes, B.C.; Giugliani, R.; Matte, U. Disruption of morphogenic and growth pathways in lysosomal storage diseases. WIREs Mech. Dis. 2021, 13, e1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellen, H.J.; Wangler, M.F.; Yamamoto, S. The fruit fly at the interface of diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of rare and common human diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, R207–R214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigon, L.; De Filippis, C.; Napoli, B.; Tomanin, R.; Orso, G. Exploiting the Potential of Drosophila Models in Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Pathological Mechanisms and Drug Discovery. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Peterson, R.T. Modeling Lysosomal Storage Diseases in the Zebrafish. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurda, B.L.; Vite, C.H. Large animal models contribute to the development of therapies for central and peripheral nervous system dysfunction in patients with lysosomal storage diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, R119–R131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Ezoe, T.; Tohyama, J.; Matsuda, J.; Vanier, M.T.; Suzuki, K. Are animal models useful for understanding the pathophysiology of lysosomal storage disease? Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 2003, 92, 54–62; discussion 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Flockhart, I.; Vinayagam, A.; Bergwitz, C.; Berger, B.; Perrimon, N.; Mohr, S.E. An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Comjean, A.; Rodiger, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chung, V.; Zirin, J.; Perrimon, N.; Mohr, S.E. FlyRNAi.org-the database of the Drosophila RNAi screening center and transgenic RNAi project: 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D908–D915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Comjean, A.; Roesel, C.; Vinayagam, A.; Flockhart, I.; Zirin, J.; Perkins, L.; Perrimon, N.; Mohr, S.E. FlyRNAi.org-the database of the Drosophila RNAi screening center and transgenic RNAi project: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D672–D678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Zidek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMBL-EBI. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. Available online: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Schrodinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0; Schrodinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Reva, B.A.; Finkelstein, A.V.; Skolnick, J. What is the probability of a chance prediction of a protein structure with an rmsd of 6 A? Fold. Des. 1998, 3, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, D.; Shravage, B.; Simin, R.; Mills, K.; Berry, D.L.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Kumar, S. Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markow, T.A. “Cost” of virginity in wild Drosophila melanogaster females. Ecol. Evol. 2011, 1, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, L.; Fowler, K. Non-mating costs of exposure to males in female Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect Physiol. 1990, 36, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiff, T.; Jacobson, J.; Cognigni, P.; Antonello, Z.; Ballesta, E.; Tan, K.J.; Yew, J.Y.; Dominguez, M.; Miguel-Aliaga, I. Endocrine remodelling of the adult intestine sustains reproduction in Drosophila. eLife 2015, 4, e06930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzl, G.; Chen, D.; Schnorrer, F.; Su, K.C.; Barinova, Y.; Fellner, M.; Gasser, B.; Kinsey, K.; Oppel, S.; Scheiblauer, S.; et al. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 2007, 448, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, A.H.; Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 1993, 118, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rera, M.; Clark, R.I.; Walker, D.W. Intestinal barrier dysfunction links metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging to death in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21528–21533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.M.; Aparicio, R.; Clark, R.I.; Rera, M.; Walker, D.W. Intestinal barrier dysfunction: An evolutionarily conserved hallmark of aging. Dis. Model. Mech. 2023, 16, dmm049969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, J.C.; Khericha, M.; Dobson, A.J.; Bolukbasi, E.; Rattanavirotkul, N.; Partridge, L. Sex difference in pathology of the ageing gut mediates the greater response of female lifespan to dietary restriction. eLife 2016, 5, e10956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudry, B.; Khadayate, S.; Miguel-Aliaga, I. The sexual identity of adult intestinal stem cells controls organ size and plasticity. Nature 2016, 530, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, J.W.; Rideout, E.J. Sex differences in Drosophila development and physiology. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2018, 6, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katarachia, S.A.; Markaki, S.P.; Velentzas, A.D.; Stravopodis, D.J. Genetic Targeting of dSAMTOR, A Negative dTORC1 Regulator, during Drosophila Aging: A Tissue-Specific Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, E. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.E.; Roman, G.; Davis, R.L. Gene expression systems in Drosophila: A synthesis of time and space. Trends Genet. 2004, 20, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southall, T.D.; Elliott, D.A.; Brand, A.H. The GAL4 System: A Versatile Toolkit for Gene Expression in Drosophila. CSH Protoc. 2008, 2008, pdb-top49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, U.; Ciesla, L. Using Drosophila as a platform for drug discovery from natural products in Parkinson’s disease. Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, U.B.; Nichols, C.D. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farfel-Becker, T.; Vitner, E.B.; Futerman, A.H. Animal models for Gaucher disease research. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ito, K.; Takahara, T.; Goto-Inoue, N.; Setou, M.; Sakata, K.; Ishida, N. Minos-insertion mutant of the Drosophila GBA gene homologue showed abnormal phenotypes of climbing ability, sleep and life span with accumulation of hydroxy-glucocerebroside. Gene 2017, 614, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.A.; Overend, G.; Dow, J.A.T.; Leader, D.P. FlyAtlas 2 in 2022: Enhancements to the Drosophila melanogaster expression atlas. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1010–D1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.; Li, R.; Oliver, B. Lipid profiles of female and male Drosophila. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, J.C.; Kuroda, M.I. Dosage compensation in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a019398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, T.; Murray, G.J.; Swaim, W.D.; Longenecker, G.; Quirk, J.M.; Cardarelli, C.O.; Sugimoto, Y.; Pastan, I.; Gottesman, M.M.; Brady, R.O.; et al. alpha-Galactosidase A deficient mice: A model of Fabry disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 2540–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunstein, H.; Papazian, M.; Maor, G.; Lukas, J.; Rolfs, A.; Horowitz, M. Misfolding of Lysosomal alpha-Galactosidase a in a Fly Model and Its Alleviation by the Pharmacological Chaperone Migalastat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J. Sex-specific regulation of aging and apoptosis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006, 127, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Suyama, K.; Buchanan, J.; Zhu, A.J.; Scott, M.P. A Drosophila model of the Niemann-Pick type C lysosome storage disease: dnpc1a is required for molting and sterol homeostasis. Development 2005, 132, 5115–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, F.; Pasini, M.E.; Intra, J.; Matsumoto, M.; Briani, F.; Hoshi, M.; Perotti, M.E. Identification and expression analysis of Drosophila melanogaster genes encoding beta-hexosaminidases of the sperm plasma membrane. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, R.; Rendic, D.; Rabouille, C.; Wilson, I.B.; Preat, T.; Altmann, F. The Drosophila fused lobes gene encodes an N-acetylglucosaminidase involved in N-glycan processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4867–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, C.; Napoli, B.; Rigon, L.; Guarato, G.; Bauer, R.; Tomanin, R.; Orso, G. Drosophila D-idua Reduction Mimics Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I Disease-Related Phenotypes. Cells 2021, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigon, L.; Kucharowski, N.; Eckardt, F.; Bauer, R. Modeling Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II in the Fruit Fly by Using the RNA Interference Approach. Life 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, S.; Prasad, M.; Datta, R. Neuromuscular degeneration and locomotor deficit in a Drosophila model of mucopolysaccharidosis VII is attenuated by treatment with resveratrol. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11, dmm036954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drosophila Ortholog | Stock ID (RRID) | Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| Gba1a | 39064 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS01984}attP2 |

| Gba1b | 38977 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS01893}attP40 |

| CG7997 | 63655 | y [1] v [1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMJ30222}attP40 |

| CG5731 | 67025 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS05491}attP40 |

| Npc1a | 37504 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS01646}attP40 |

| Npc2a | 38237 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS01681}attP40 |

| Hexo1 | 67312 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMC06416}attP40 |

| Hexo2 | 57199 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMC04581}attP40 |

| GCS2alpha | 34334 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS01322}attP2 |

| tobi | 53379 | y [1] v [1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMJ02101}attP40 |

| Idua | 64931 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMC05804}attP2 |

| Ids | 51901 | y [1] v [1]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMC03475}attP40 |

| CG15117 | 33693 | y [1] sc[*] v [1] sev [21]; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = TRiP.HMS00562}attP2 |

| Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) | Human Gene | Protein Name | Drosophila Ortholog | Homology (Rank)/ (DIOPT Score) | RNAi Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia type 48 (SPG48) | AP5Z1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 5 subunit zeta 1 | Lpin/CG8709 | Low (1) | 63614 1 |

| 77170 1 | |||||

| 2. Disorders of lysosomal amino acid transport | |||||

| A. Cystinosis | CTNS | Cystinosin, Lysosomal Cystine transporter | Ctns/ CG17119 | High (16) | 40823 1 |

| B. Free sialic acid storage disease (free SASD) | |||||

| (a) Salla disease (SD) | SLC17A5 | Sialin, Solute carrier family 17 member 5 | VGlut2/MFS9/CG4288 | High (10) | 29305 1 |

| (b) Intermediate severity Salla disease | v104145 2 | ||||

| (c) Infatile free sialic acid storage disease (ISSD) | |||||

| 3. Disorders of sialic acid metabolism | |||||

| Sialuria | GNE | Glucosamine (UDP-N-acetyl)-2-epimerase/N-Acetyl-mannosamine kinase | - | - | - |

| 4. Glycoproteinoses | |||||

| A. Mucolipidoses (ML) | |||||

| (a) ML type II α/β: Inclusion (I)- cell disease | GNPTAB | N-Acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphotransferase subunits α/β | Gnptab/ CG8027 | High (15) | v109400 2 |

| (b) ML type III: Pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy: | |||||

| type III α/β | GNPTG | N-Acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphotransferase subunit γ | GCS2beta/ CG6453 | Moderate (3) | 35008 1 |

| type III γ | CG7685 | Low (2) | 62254 1 | ||

| (c) ML type IV: Sialolipidosis | MCOLN1 | Mucolipin 1, Mucolipin transient receptor potencial (TRP) cation channel 1 | CG42638 | Moderate (14) | 44098 1 |

| Trpml/ CG8743 | Moderate (14) | 31294 1 | |||

| 31673 1 | |||||

| v108088 2 | |||||

| v45989 2 | |||||

| B. Oligosaccharidoses | |||||

| (a) α-Mannosidosis | MAN2B1 | Lysosomal α-Mannosidase, Mannosidase alpha class 2B member 1 | LManII/ CG6206 | High (16) | 53294 1 |

| LManI/ CG5322 | Moderate (14) | 44473 1 | |||

| LManV/ CG9466 | Moderate (14) | v104300 2 | |||

| v13040 2 | |||||

| LManIV/ CG9465 | Moderate (14) | 66992 1 | |||

| LManIII/ CG9463 | Moderate (13) | v15589 2 | |||

| v48063 2 | |||||

| LManVI/ CG9468 | Moderate (12) | 61216 1 | |||

| alpha-Man-IIa/CG18802 | Low (3) | v5838 2 | |||

| alpha-Man-IIb/CG4606 | Low (2) | v108043 2 | |||

| v42652 2 | |||||

| (b) β-Mannosidosis | MANBA | β-Mannosidase | beta-Man/ CG12582 | High (14) | 53272 1 |

| (c) Fucosidosis | FUCA1 | α-L-Fucosidase 1 | Fuca/ CG6128 | High (13) | - |

| (d) Aspartyglucosaminuria (AGU) | AGA | Aspartylglucosaminidase | CG1827 | High (14) | 65141 1 |

| CG10474 | High (14) | 51444 1 | |||

| CG4372 | Moderate (8) | v36431 2 | |||

| CG7860 | Low (2) | v108281 2 | |||

| v34394 2 | |||||

| Tasp1/ CG5241 | Low (2) | 64907 1 | |||

| (e) α-Ν-Acetyl- galactosaminidase deficiency (NAGA deficiency): Schindler disease: | |||||

| type I: Infantile onset Neuroaxonal dystrophy | NAGA | α-N-Acetyl-galactosaminidase | CG5731 | High (16) | 67025 1 |

| type II: Kanzaki disease | CG7997 | Moderate (15) | 63655 1 | ||

| type III: Intermediate severity | 57781 1 | ||||

| (f) Galactosialidosis: Goldberg syndrome | CTSA | Protective protein Cathepsin A, and a secondary deficiency in β-Galactosidase and Neuraminidase-1 | CG4572 | Moderate (4) | 34337 1 |

| CG32483 | Low (2) | v106263 2 | |||

| v22976 2 | |||||

| hiro/CG3344 | Low (2) | v110402 2 | |||

| v15213 2 | |||||

| CG31821 | Low (2) | v106059 2 | |||

| v15496 2 | |||||

| CG31823 | Low (2) | 66941 1 | |||

| 67027 1 | |||||

| (g) Sialidosis: | |||||

| type I (ST-1): Cherry-red spot- myoclonus syndrome | NEU1 | Neuraminidase-1, Lysosomal Sialidase | - | - | - |

| type II (ST-2): Mucolipidosis I | |||||

| 5. Lysosomal acid phosphatase deficiency | |||||

| 6. Glycogen storage disease(s) [GSD(s)] | |||||

| GSD type II (due to acid maltase deficiency): Pompe disease | GAA | Lysosomal α-Glucosidase, Acid maltase | GCS2alpha/ CG14476 | Moderate (5) | 34334 1 |

| tobi/ CG11909 | Low (3) | 53379 1 | |||

| CG33080 | Low (2) | 42554 1 | |||

| GSD due to LAMP-2 deficiency: Danon disease | LAMP2 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 | Lamp1/ CG3305 | Moderate (8) | 38335 1 |

| 38254 1 | |||||

| CG32225 | Low (3) | v102345 2 | |||

| v5383 2 | |||||

| 7. Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs) | |||||

| MPS I | |||||

| Hurler syndrome (MPSIH) | IDUA | α-L-Iduronidase | Idua/CG6201 | High (14) | 64931 1 |

| Hurler-Scheie syndrome (MPSIH/S) | |||||

| Scheie syndrome (MPSIS) | |||||

| MPS II: Hunter syndrome | |||||

| type A (MPSIIA), severe form | IDS | Iduronate 2-sulfatase | Ids/CG12014 | High (18) | 51901 1 |

| type B (MPSIIB), attenuated form | 63004 1 | ||||

| MPS III: Sanfilippo syndrome | |||||

| type A (MPSIIIA) | SGSH | N-Sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase | Sgsh/ CG14291 | High (16) | v107384 2 |

| v16897 2 | |||||

| type B (MPSIIIB) | NAGLU | N-Acetyl-α-glucosaminidase | Naglu/ CG13397 | High (17) | 51808 1 |

| type C (MPSIIIC) | HGSNAT | Heparan-α-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase | Hgsnat/ CG6903 | High (15) | 33423 1 |

| type D (MPSIIID) | GNS | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase | Gns/ CG18278 | High (15) | 28520 1 |

| 51878 1 | |||||

| v109944 2 | |||||

| v22936 2 | |||||

| MPS IV: Morquio syndrome | |||||

| type A (MPSIVA) | GALNS | N-Acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase | CG7408 | Moderate (3) | 65359 1 |

| Gns/ CG18278 | Moderate (3) | 28520 1 | |||

| 51878 1 | |||||

| CG7402 | Moderate (3) | v103947 2 | |||

| v37302 2 | |||||

| CG32191 | Moderate (3) | v101578 2 | |||

| v14294 2 | |||||

| type B (MPSIVB) | GLB1 | β-Galactosidase 1 | Ect3/CG3132 | Moderate (15) | 62217 1 |

| Gal/CG9092 | Moderate (14) | 42922 1 | |||

| 50680 1 | |||||

| MPS VI: Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome | ARSB | Arylsulfatase B | CG7402 | High (13) | v103947 2 |

| v37302 2 | |||||

| MPS VII: Sly disease | GUSB | β-Glucuronidase | CG15117 | High (17) | 33693 1 |

| beta-Glu/CG2135 | Moderate (15) | 62236 1 | |||

| beta-Man/ CG12582 | Low (2) | 53272 1 | |||

| MPS IX: Hyaluronidase deficiency | HYAL1 | Hyaluronidase 1 | - | - | - |

| 8. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL): Batten disease | |||||

| CLN1: Haltia–Santavuori disease /Hagberg–Santavuori disease/ Santavuori disease (INCL) | PPT1 | Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 | Ppt1/ CG12108 | High (14) | 55331 1 |

| 62291 1 | |||||

| 25952 1 | |||||

| Ppt2/ CG4851 | Low (3) | 28362 1 | |||

| v106819 2 | |||||

| v14592 | |||||

| CLN2: Jansky–Bielschowsky disease (LINCL) | TPP1 | Tripeptidyl peptidase 1 | - | - | - |

| CLN3: Batten–Spielmeyer–Sjogren disease (JNCL) | CLN3 | Battenin, Endosomal transmembrane protein | Cln3/ CG5582 | High (14) | 35734 1 |

| CLN4: Parry disease/Kufs disease type A and B (ANCL) | DNAJC5 | Cysteine string protein, DnaJ Heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C5 | Csp/CG6395 | High (14) | 33645 1 |

| 31290 1 | |||||

| 31669 1 | |||||

| CG7130 | Low (2) | 57854 1 | |||

| CG7133 | Low (2) | 60459 1 | |||

| 42820 1 | |||||

| l(3)80Fg/ CG40178 | Low (2) | 44578 1 | |||

| CLN5: Finnish variant | CLN5 | Ceroid-lipofuscinosis neuronal protein 5 | - | - | - |

| CLN6: Lake–Cavanagh or Indian variant | CLN6 | Transmembrane ER protein | - | - | - |

| CLN7: Turkish variant | MFSD8 | Major-facilitator superfamily domain containing 8 | Cln7/ CG8596 | High (16) | 61960 1 |

| 55664 1 | |||||

| rtet/CG5760 | Low (2) | v110473 2 | |||

| v44002 2 | |||||

| CLN8: Northern epilepsy/ Epilepsy mental retardation | CLN8 | Protein CLN8, Transmembrane ER and ERGIC protein | CG17841 | Moderate (3) | 34948 1 |

| CLN9 | N/A | N/A | |||

| CLN10: Congenital NCL | CTSD | Cathepsin D, Lysosomal Aspartyl peptidase/protease | cathD/ CG1548 | High (16) | 28978 1 |

| 53882 1 | |||||

| 55178 1 | |||||

| CLN11 | GRN | Granulin (precursor) | CG15011 | Low (1) | 58284 1 |

| 31589 1 | |||||

| NimC2/ CG18146 | Low (1) | 25960 1 | |||

| v3120 2 | |||||

| v362612 | |||||

| CLN12: Kufor–Raked syndrome/ PARK9/Juvenile Parkinsonism—NCL | ATP13A2 | Cation-transporting ATPase 13A2, PARK9 | anne/ CG32000 | Moderate (13) | 44005 1 |

| 30499 1 | |||||

| CG6230 | Low (3) | 77371 1 | |||

| SPoCk/ CG32451 | Low (2) | 44040 1 | |||

| 28352 1 | |||||

| CLN13 | CTSF | Cathepsin F | CtsF/ CG12163 | High (14) | 33955 1 |

| CLN14: Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3 | KCTD7 | Potassium channel tetramerization domain containing 7 | Ktl/CG10830 | Moderate (2) | 57171 1 |

| 25848 1 | |||||

| CG14647 | Moderate (2) | 60064 1 | |||

| 27032 1 | |||||

| twz/ CG10440 | Moderate (2) | 57397 1 | |||

| 25846 1 | |||||

| 9. Pycnodysostosis: Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome—Osteopetrosis acro-osteolytica | CTSK | Cathepsin K | CtsL1/ CG6692 | Moderate (8) | 41939 1 |

| 32932 1 | |||||

| 10. Sphingolipidoses | |||||

| A. Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (ASMD) | |||||

| Niemann–Pick disease types A and B | SMPD1 | Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase | Asm/CG3376 | High (17) | 36760 1 |

| CG15533 | Moderate (8) | 36761 1 | |||

| CG15534 | Moderate (8) | 36762 1 | |||

| CG32052 | Moderate (6) | 36763 1 | |||

| B. Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia with late-onset spasticity (due to GBA2 deficiency) | GBA2 | β-Glucosylceramidase 2 | CG33090 | High (18) | 36688 1 |

| C. Encephalopathy due to prosaposin deficiency— Combined PSAP deficiency (PSAPD) | PSAP | Prosaposin | Sap-r/ CG12070 | High (14) | v51129 2 |

| v51130 2 | |||||

| D. Fabry disease—Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum | GLA | α-Galactosidase A | CG7997 | Moderate (14) | 63655 1 |

| 57781 1 | |||||

| CG5731 | Moderate (13) | 67025 1 | |||

| E. Farber lipogranulomatosis | ASAH1 | Acid Ceramidase | - | - | - |

| F. Gangliosidoses | |||||

| (a) GM1 gangliosidosis: Landing disease: | |||||

| type I (infantile): Norman–Landing disease | GLB1 | β-Galactosidase | Ect3/CG3132 | Moderate (15) | 62217 1 |

| type II (juvenile—late infantile) | Gal/CG9092 | Moderate (14) | 50680 1 | ||

| type III (adult) | 42922 1 | ||||

| (b) GM2 gangliosidosis: | |||||

| Tay–Sachs disease (B variant) | HEXA | β-Hexosaminidase subunit α | Hexo1/ CG1318 | Moderate (13) | 67312 1 |

| Hexo2/ CG1787 | Moderate (12) | 57199 1 | |||

| fdl/CG8824 | Moderate (11) | 52987 1 | |||

| 28298 1 | |||||

| Sandhoff disease (0 variant) | HEXB | β-Hexosaminidase subunit β | Hexo1/ CG1318 | High (14) | 67312 1 |

| Hexo2/ CG1787 | Moderate (12) | 57199 1 | |||

| fdl/CG8824 | Moderate (12) | 52987 1 | |||

| 28298 1 | |||||

| (c) GM2 activator deficiency (AB variant) | GM2A | GM2 Ganglioside activator | - | - | - |

| G. Gaucher disease (GD) | |||||

| GD type 1 | GBA1 | β-Glucocerebrosidase 1/β-Glucosidase 1 | Gba1a/ CG31148 | High (15) | 38379 1 |

| GD type 2 | 39064 1 | ||||

| GD type 3 | Gba1b/ CG31414 | High (15) | 38970 1 | ||

| Fetal/Perinatal lethal Gaucher disease | 38977 1 | ||||

| Atypical Gaucher disease due to Saposin C deficiency | PSAP | Prosaposin | Sap-r/ CG12070 | High (14) | v51129 2 |

| v51130 2 | |||||

| Gaucher-like disease/ Gaucher disease- ophthalmoplegia-cardiovascular calcification syndrome/Gaucher disease type 3C | GBA1 | β-Glucosylceramidase 1 | Gba1a/ CG31148 | High (15) | 38379 1 |

| 39064 1 | |||||

| Gba1b/ CG31414 | High (15) | 38970 1 | |||

| 38977 1 | |||||

| H. Globoid cell leukodystrophy— Krabbe disease | GALC | Galactosylceramidase | - | - | - |

| I. Lipid storage disease | |||||

| (a) Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency | |||||

| Cholesterol ester storage disease | LIPA | Lipase A lysosomal acid type, Cholesterol ester hydrolase | Lip3/CG8823 | High (15) | 65025 1 |

| Wolman disease | |||||

| (b) Niemann–Pick disease type C: | |||||

| type C1 | NPC1 | NPC Intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 | Npc1a/ CG5722 | High (16) | 37504 1 |

| Npc1b/ CG12092 | Moderate (11) | 38296 1 | |||

| SCAP/ CG33131 | Low (2) | 31566 1 | |||

| type C2 | NPC2 | NPC Intracellular cholesterol transporter 2 | Npc2a/ CG7291 | High (16) | 38237 1 |

| Npc2b/ CG3153 | Moderate (7) | 38238 1 | |||

| 42914 1 | |||||

| Npc2d/ CG12813 | Moderate (6) | v31095 2 | |||

| Npc2c/ CG3934 | Moderate (6) | 61315 1 | |||

| Npc2e/ CG31410 | Moderate (6) | 67956 1 | |||

| Npc2f/ CG6164 | Moderate (4) | v102172 2 | |||

| v12915 2 | |||||

| Npc2h/ CG11315 | Moderate (3) | 67803 1 | |||

| Npc2g/ CG11314 | Moderate (3) | 63030 1 | |||

| J. Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) | ASRA PSAP | Arylsulfatase A Prosaposin | |||

| K. Multiple Sulfatase deficiency (MSD)/Mucosulfatidosis | SUMF1 | Sulfatase modifying factor 1, Formylglycine-generating enzyme | CG7049 | High (14) | 51896 1 |

| Action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome/Myoclonus-nephropathy syndrome/Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 | SCARB2 | Scavenger receptor class B member 2, Lysosomal integral membrane protein II | emp/ CG2727 | High (15) | 40947 1 |

| Modeled Disease | Human Gene | Drosophila Ortholog | Neuronal Lifespan | Neuronal Climbing | Midgut Lifespan | Sex Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaucher | GBA1 | Gba1a | +++ | ++ | + | Male-biased |

| Gba1b | +++ | ++ | + | Male-biased | ||

| Fabry | GLA | CG7997 | - | n.d. | - | None |

| CG5731 | + | ++ | +++ | Female-biased | ||

| Niemann–Pick C | NPC1 | Npc1a | +++ | +++ | ++ | Male-biased |

| NPC2 | Npc2a | +++ | - | + | Male-biased | |

| Tay–Sachs/ Sandhoff | HEXA/ HEXB | Hexo1 | - | n.d. | - | None |

| Hexo2 | ++ | n.d. | - | Male-biased | ||

| Pompe | GAA | GCS2alpha | + | n.d. | - | Male-biased |

| tobi | - | n.d. | - | None | ||

| Hurler | IDUA | Idua | ++ | ++ | - | Male-biased |

| Hunter | IDS | Ids | + | n.d. | - | Male-biased |

| Sly | GUSB | CG15117 | + | ++ | ++ | Male-biased |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Markaki, S.P.; Kiose, N.M.; Charitopoulou, Z.A.; Kougioumtzoglou, S.; Velentzas, A.D.; Stravopodis, D.J. Genetic Modeling of Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) in the Brain–Midgut Axis of Drosophila melanogaster During Aging. Cells 2026, 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010006

Markaki SP, Kiose NM, Charitopoulou ZA, Kougioumtzoglou S, Velentzas AD, Stravopodis DJ. Genetic Modeling of Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) in the Brain–Midgut Axis of Drosophila melanogaster During Aging. Cells. 2026; 15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkaki, Sophia P., Nikole M. Kiose, Zoi A. Charitopoulou, Stylianos Kougioumtzoglou, Athanassios D. Velentzas, and Dimitrios J. Stravopodis. 2026. "Genetic Modeling of Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) in the Brain–Midgut Axis of Drosophila melanogaster During Aging" Cells 15, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010006

APA StyleMarkaki, S. P., Kiose, N. M., Charitopoulou, Z. A., Kougioumtzoglou, S., Velentzas, A. D., & Stravopodis, D. J. (2026). Genetic Modeling of Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) in the Brain–Midgut Axis of Drosophila melanogaster During Aging. Cells, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010006