Low-Density Lipoproteins Induce a Pro-Inflammatory, Chemotactic Mox-like Phenotype in THP-1-Derived Human Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Macrophage Differentiation

2.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Measurement

2.5. Static Adhesion Assay

2.6. µ-Slide Chemotaxis Assay

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

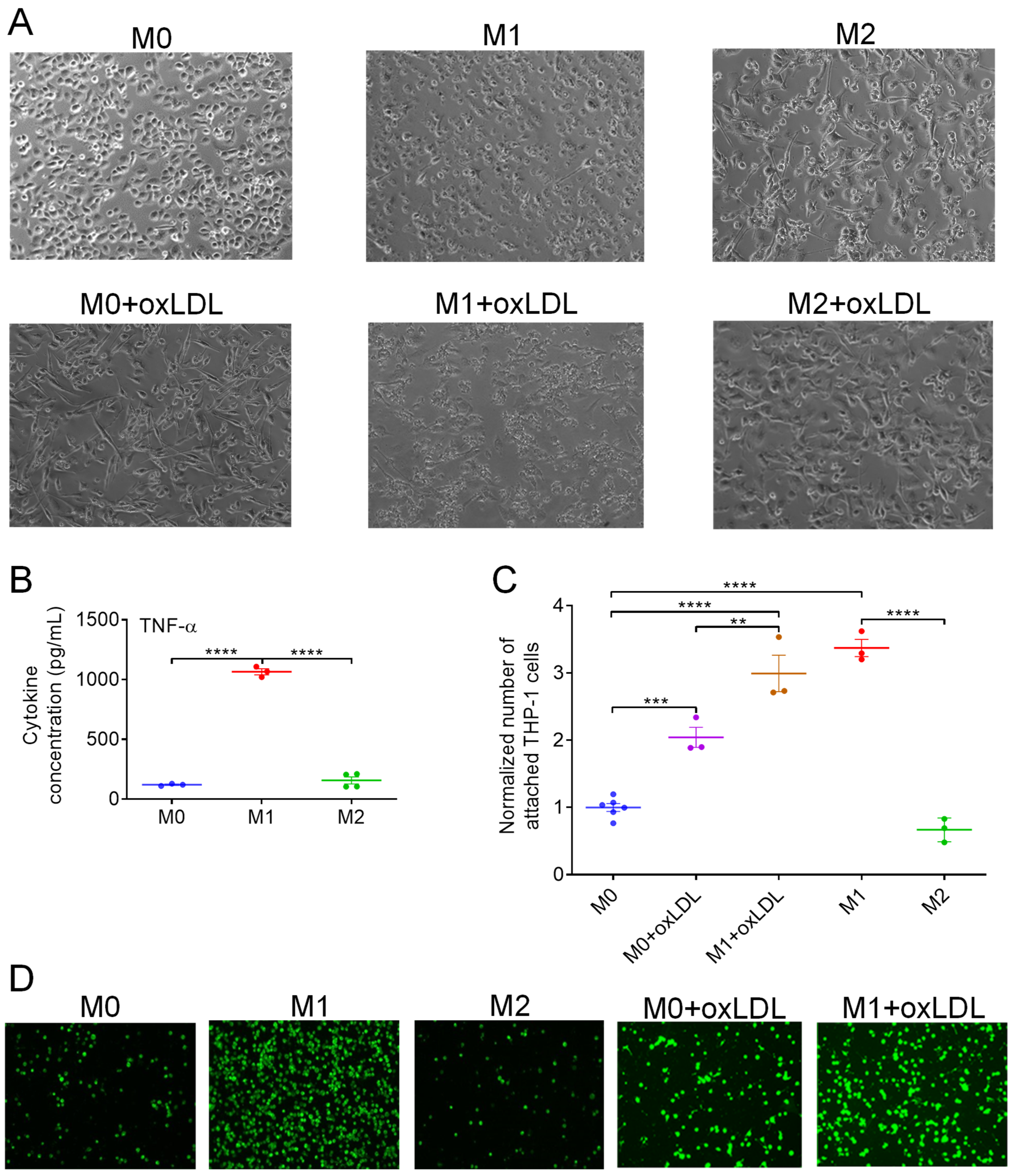

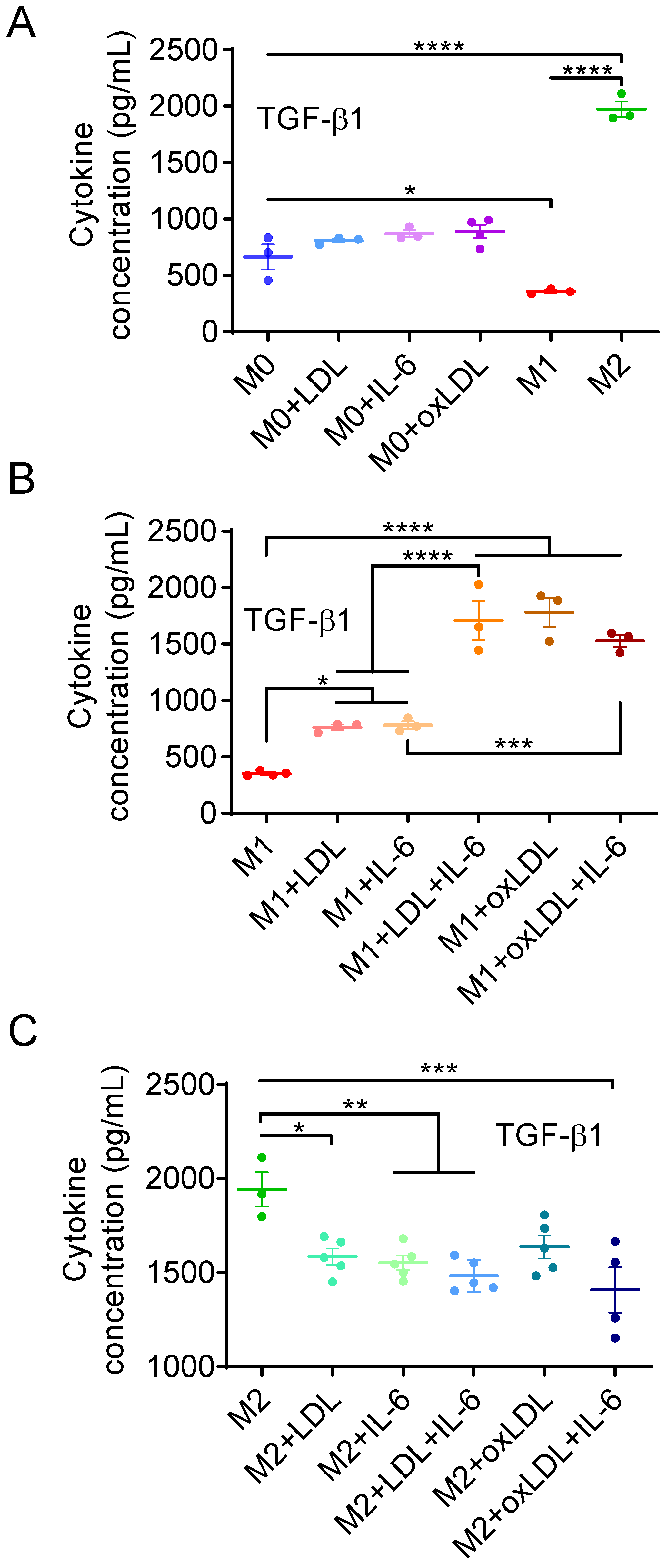

3.1. OxLDL Induces the Polarization of M0 MΦs Toward a Hybrid Mox-like Phenotype

3.2. OxLDL or LDL in Combination with IL-6 Induces the Polarization of M1-like MΦs into a Mox-like Phenotype

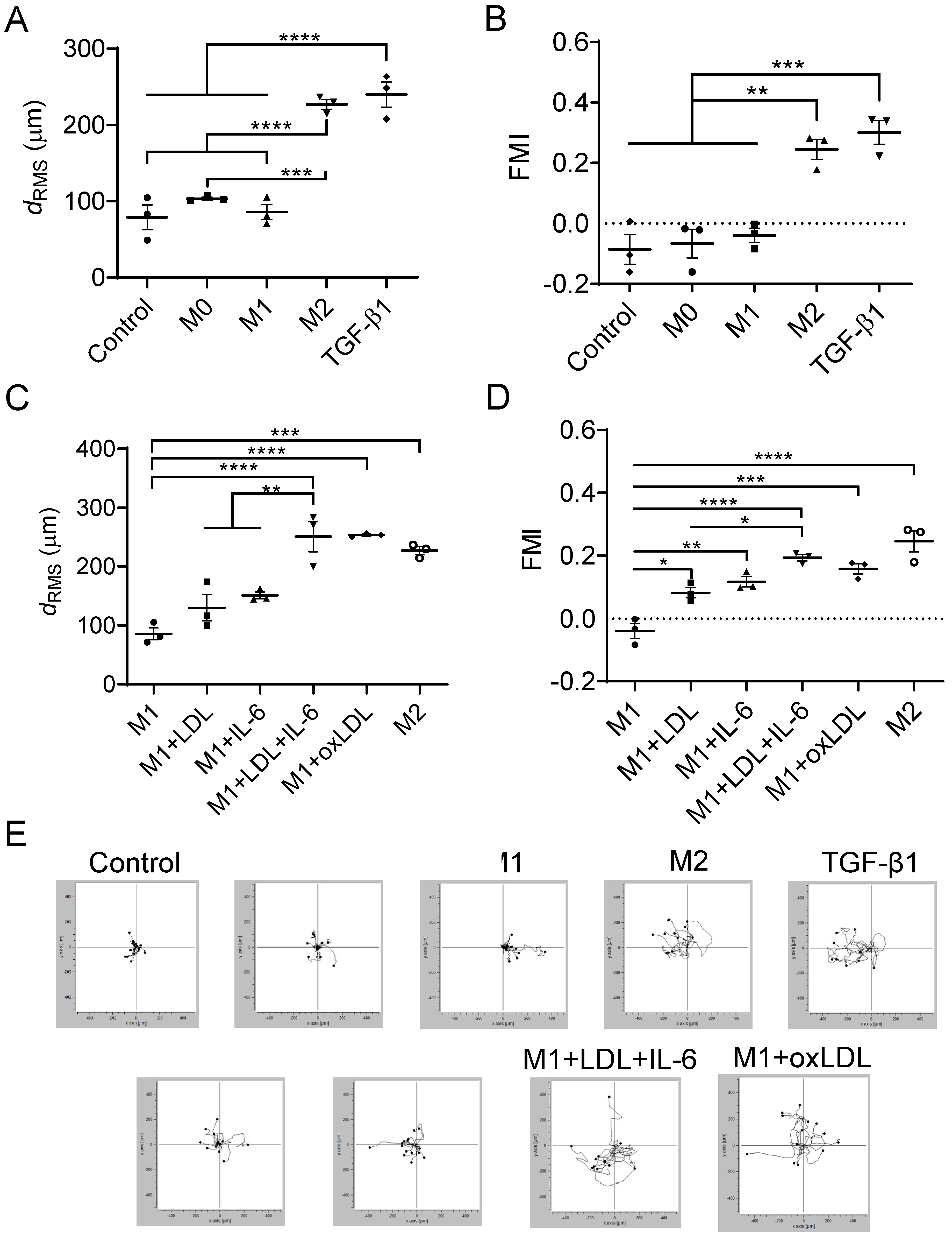

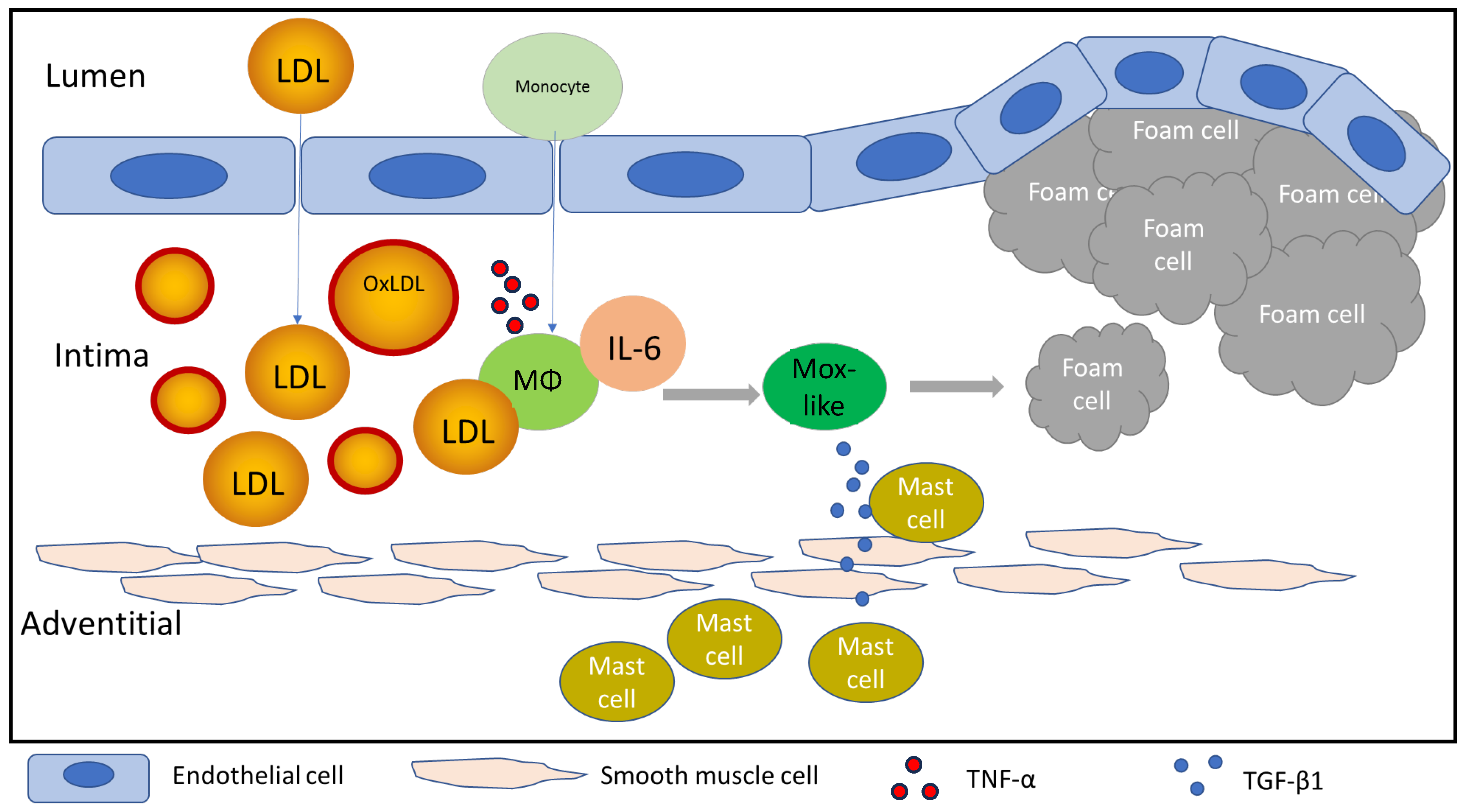

3.3. Mast Cells Migrate Toward Mox-like MΦs

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Li, W.; Zhong, J. Targeting Macrophage Phenotypes and Metabolism as Novel Therapeutic Approaches in Atherosclerosis and Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2024, 26, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Torra, I.; Gage, M.; de Juan, A.; Pello, O.M. Isolation, Culture, and Polarization of Murine Bone Marrow-Derived and Peritoneal Macrophages. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1339, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, L.S.; Mogensen, C.K.; Rosendahl, A.; Cucak, H.; Nielsen, L.B.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Pedersen, T.X. Bone marrow-derived and peritoneal macrophages have different inflammatory response to oxLDL and M1/M2 marker expression—Implications for atherosclerosis research. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Tse, M.J.; Read, E.L.; Liu, W.F. Regulation of macrophage polarization and plasticity by complex activation signals. Integr. Biol. 2016, 8, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadl, A.; Meher, A.K.; Sharma, P.R.; Lee, M.Y.; Doran, A.C.; Johnstone, S.R.; Elliott, M.R.; Gruber, F.; Han, J.; Chen, W.; et al. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanput, W.; Mes, J.J.; Wichers, H.J. THP-1 cell line: An in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, J.F.; Manica, A.; Crestani, P.; Dutzmann, J.; Folco, E.J.; Weber, H.; Libby, P.; Croce, K. Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Induces Macrophage Production of Prothrombotic Microparticles. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Khismatullin, D.B. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein contributes to atherogenesis via co-activation of macrophages and mast cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjeltia, K.Z.; Legssyer, I.; Van Antwerpen, P.; Kisoka, R.L.; Babar, S.; Moguilevsky, N.; Delree, P.; Ducobu, J.; Remacle, C.; Vanhaeverbeek, M.; et al. Triggering of inflammatory response by myeloperoxidase-oxidized LDL. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 84, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, L.; Tontonoz, P.; Alvarez, J.G.A.; Chen, H.; Evans, R.M. Oxidized LDL Regulates Macrophage Gene Expression through Ligand Activation of PPARγ. Cell 1998, 93, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Guzmán, O.J.; Gil-Izquierdo, Á.; Medina, S.; Osorio, E.; Álvarez-Quintero, R.; Zuluaga, N.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.-M.; Durand, T.; Muñoz-Durango, K. Oxidized LDL triggers changes in oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers in human macrophages. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeradeh, E.; Frangie, C.; Bazzi, S.; Daher, J. The in vitro effect of myeloperoxidase oxidized LDL on THP-1 derived macrophages. Innate Immun. 2024, 30, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, F.J.; Koga, M.M.; Pecenin, M.; Ferracini, M.; Gidlund, M.; Jancar, S. Oxidized LDL induces alternative macrophage phenotype through activation of CD36 and PAFR. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 198193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, B.L.; Marchese, M.J.; Kew, R.R. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 mediates mast cell chemotaxis. J. Immunol. 1994, 152, 5860–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halova, I.; Draberova, L.; Draber, P. Mast cell chemotaxis—Chemoattractants and signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, N.; Piek, E.; ten Dijke, P.; Nilsson, G. Human mast cell migration in response to members of the transforming growth factor-beta family. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 67, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Quax, P.H.; Kuiper, J.; Bot, I. The role of mast cells in atherosclerosis. Hamostaseologie 2015, 35, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Bot, I.; Rodríguez-González, M.; Maurer, M. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Mast Cells in Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression and Destabilization. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 66, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.M.; Shi, G.P. Emerging role of mast cells and macrophages in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 71–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstedt, K.A.; Mayranpaa, M.I.; Kovanen, P.T. Mast cells in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques—A view to a kill. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, M.; Penttila, A.; Kovanen, P.T. Accumulation of activated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Circulation 1994, 90, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Khismatullin, D.B. Synergistic effect of histamine and TNF-α on monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelial cells. Inflammation 2013, 36, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Leake, D. Inhibition of Lysosomal Oxidation of Ldl Prevents Lysosomal Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, Secretion of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Human Macrophages and Reduces Atherosclerosis in Mice. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öörni, K.; Kovanen, P.T. Aggregation Susceptibility of Low-Density Lipoproteins-A Novel Modifiable Biomarker of Cardiovascular Risk. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didion, S.P. Cellular and Oxidative Mechanisms Associated with Interleukin-6 Signaling in the Vasculature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassmann, S.; Stumpf, M.; Strehlow, K.; Schmid, A.; Schieffer, B.; Böhm, M.; Nickenig, G. Interleukin-6 induces oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction by overexpression of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidadavolu, L.S.; Cosarderelioglu, C.; Merino Gomez, A.; Wu, Y.; Bopp, T.; Zhang, C.; Nguyen, T.; Marx-Rattner, R.; Yang, H.; Antonescu, C.; et al. Interleukin-6 Drives Mitochondrial Dysregulation and Accelerates Physical Decline: Insights From an Inducible Humanized IL-6 Knock-In Mouse Model. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 1740–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.R.; Reyes, J.L.; Iannuzzi, J.; Leung, G.; McKay, D.M. The pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6, enhances the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E., L.; Fragakis, N.; Ioannidou, E.; Bounda, A.; Theodoridou, S.; Klonizakis, P.; Garipidou, V. Increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines in children with family history of coronary artery disease. Clin. Cardiol. 2010, 33, E6–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, T.M.; Steinke, J.W.; Tiñana, A.M.; Feng, C.; Xing, W.; Lam, B.K.; Paruchuri, S.; Boyce, J.A.; Borish, L. Characterization of a novel human mast cell line that responds to stem cell factor and expresses functional FcεRI. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 815–822.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.A.; Yang, Y.; Makowski, L.; Troester, M.A. Basal-like breast cancer cells induce phenotypic and genomic changes in macrophages. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinsky, B.; Hagbi-Levi, S.; Elbaz-Hayoun, S.; Grunin, M.; Chowers, I. Characterizing the effect of supplements on the phenotype of cultured macrophages from patients with age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 2017, 23, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ley, K.; Laudanna, C.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Nourshargh, S. Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susser, L.I.; Rayner, K.J. Through the layers: How macrophages drive atherosclerosis across the vessel wall. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e157011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobryshev, Y.V. Monocyte recruitment and foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. Micron 2006, 37, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Tang, B.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Huang, S.; Liu, C. Macrophages in cardiovascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Guo, M.; Wang, Z.; Liu, K. Tissue-Resident Macrophages in Cardiovascular Diseases: Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; He, S.; Song, Z.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Sun, H.; Zhou, P.; Peng, Q.; Du, S.; Zheng, S.; et al. Macrophage polarization states in atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1185587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagov, A.V.; Markin, A.M.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Orekhov, A.N. The Role of Macrophages in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Cells 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, C.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Laouini, D. Role of Human Macrophage Polarization in Inflammation during Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, M.; Paolini, L.; Vinatier, E.; Mantovani, A.; Delneste, Y.; Jeannin, P. Antitumor strategies targeting macrophages: The importance of considering the differences in differentiation/polarization processes between human and mouse macrophages. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Pradhan, P.; Braud, L.; Fuchs, H.R.; Gueler, F.; Motterlini, R.; Foresti, R.; Immenschuh, S. Human and murine macrophages exhibit differential metabolic responses to lipopolysaccharide—A divergent role for glycolysis. Redox Biol. 2019, 22, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, H. Regulation of iNOS on Immune Cells and Its Role in Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuninaka, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Ishigami, A.; Nosaka, M.; Matsuki, J.; Yasuda, H.; Kofuna, A.; Kimura, A.; Furukawa, F.; Kondo, T. Macrophage polarity and wound age determination. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, F.R.; Mozetic, P.; Fioramonti, M.; Iuliani, M.; Ribelli, G.; Pantano, F.; Santini, D.; Tonini, G.; Trombetta, M.; Businaro, L.; et al. Classification of M1/M2-polarized human macrophages by label-free hyperspectral reflectance confocal microscopy and multivariate analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K.; Allavena, P.; Mantovani, A. Tumor-associated macrophages: Functional diversity, clinical significance, and open questions. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albina, J.E. On the expression of nitric oxide synthase by human macrophages. Why no NO? J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995, 58, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.E.; Shandilya, H.; Kepka-Lenhart, D.; Poljakovic, M.; Ghosh, A.; Morris, S.M., Jr. Shaping the murine macrophage phenotype: IL-4 and cyclic AMP synergistically activate the arginase I promoter. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 2290–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kuang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. TGF-β1 secreted by M2 phenotype macrophages enhances the stemness and migration of glioma cells via the SMAD2/3 signalling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 3395–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, S.Y.; Ziblat, A.; Secchiari, F.; Torres, N.I.; Sierra, J.M.; Raffo Iraolagoitia, X.L.; Araya, R.E.; Domaica, C.I.; Fuertes, M.B.; Zwirner, N.W. Human M2 Macrophages Limit NK Cell Effector Functions through Secretion of TGF-β and Engagement of CD85j. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, W.; Zhang, J. A richer and more diverse future for microglia phenotypes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, M.H.; Hauck, F.; Dreyer, J.H.; Kempkes, B.; Niedobitek, G. Macrophage polarisation: An immunohistochemical approach for identifying M1 and M2 macrophages. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Korthuis, R.J. Mast Cell Proteases and Inflammation. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models 2011, 8, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, K. The role of mast cells in allergic inflammation. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peavy, R.D.; Metcalfe, D.D. Understanding the mechanisms of anaphylaxis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 8, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, G. Mast cell and autoimmune diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 246126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valent, P. Risk factors and management of severe life-threatening anaphylaxis in patients with clonal mast cell disorders. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. TGF-beta signaling-dependent alleviation of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 4977–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Kim, B.; Abdulkhaliq, A.A.; Ren, J.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Borai, A.; Khan, J.; Pratico, D. Dual role of microglia in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 216, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Driscoll, C.M. The blood-brain barrier in aging and neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouck, B.; Fenart, L.; Dehouck, M.P.; Pierce, A.; Torpier, G.; Cecchelli, R. A new function for the LDL receptor: Transcytosis of LDL across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 138, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, Y.; David, M.; Varini, K.; Jabès, F.; Gaudin, N.; Fortoul, A.; Bakloul, K.; Masse, M.; Bernard, A.; Drobecq, L.; et al. Use of LDL receptor-targeting peptide vectors for in vitro and in vivo cargo transport across the blood-brain barrier. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1807–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shie, F.S.; Neely, M.D.; Maezawa, I.; Wu, H.; Olson, S.J.; Jürgens, G.; Montine, K.S.; Montine, T.J. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein is present in astrocytes surrounding cerebral infarcts and stimulates astrocyte interleukin-6 secretion. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 164, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L.B.; Toth, P.P.; Dearborn-Tomazos, J.L.; Giugliano, R.P.; Hirsh, B.J.; Peña, J.M.; Selim, M.H.; Woo, D.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; et al. Aggressive LDL-C Lowering and the Brain: Impact on Risk for Dementia and Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, e404–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, K.K.; Zeidler, M.; Kalpachidou, T.; Kress, M. Role of IL-6 in the regulation of neuronal development, survival and function. Cytokine 2021, 144, 155582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, I.L.; Abraham, C.R.; Masliah, E.; Kemper, P.; Inglis, J.D.; Oldstone, M.B.; Mucke, L. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10061–10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-X.; Agbana, Y.L.; Sun, Z.-S.; Fei, S.-W.; Zhao, H.-Q.; Zhou, X.-N.; Chen, J.-H.; Kassegne, K. Increased interleukin-6 is associated with long COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappelmann, N.; Dantzer, R.; Khandaker, G.M. Interleukin-6 as potential mediator of long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms of COVID-19. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 131, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.; Warnke, K.; Siebenhaar, F.; Peters, E.M.; Nitsch, R.; Maurer, M. The majority of brain mast cells in B10.PL mice is present in the hippocampal formation. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 392, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, K.M.; Dailey, C.A.; Jahn, J.L.; Rodriquez, E.; Son, N.H.; Sweedler, J.V.; Silver, R. Serotonin of mast cell origin contributes to hippocampal function. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 36, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, K.M.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Pfaff, D.W.; Silver, R. Brain mast cells link the immune system to anxiety-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18053–18057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.K.; Nair, A.; Gupta, M. Mast Cells in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, X.; Yang, H.; Hu, G.; He, S. Mast cell tryptase induces microglia activation via protease-activated receptor 2 signaling. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 29, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen, E.; van Bergeijk, D.; Oosting, R.S.; Redegeld, F.A. Mast cells in neuroinflammation and brain disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Giusti, P.; Facci, L. Microglia and mast cells: Two tracks on the road to neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 3103–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, J.K.; Kulka, M. Decoding Mast Cell-Microglia Communication in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; López-Arrieta, J.; Lipschitz, S.; Doskas, T.; Spiru, L.; Moroz, S.; Venger, O.; Vermersch, P.; Moussy, A.; Mansfield, C.D.; et al. Masitinib for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3, clinical trial. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.J.; Luo, S.F.; Lai, J.H. Biological effects of interleukin-6: Clinical applications in autoimmune diseases and cancers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 97, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, M.; Moriya, Y.; Kishimoto, T.; Ohsugi, Y. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) induces the proliferation of synovial fibroblastic cells in the presence of soluble IL-6 receptor. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1995, 34, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, H.; Josi, R.R.; Khanna, A.; Khismatullin, D.B. Low-Density Lipoproteins Induce a Pro-Inflammatory, Chemotactic Mox-like Phenotype in THP-1-Derived Human Macrophages. Cells 2026, 15, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010055

Yu H, Josi RR, Khanna A, Khismatullin DB. Low-Density Lipoproteins Induce a Pro-Inflammatory, Chemotactic Mox-like Phenotype in THP-1-Derived Human Macrophages. Cells. 2026; 15(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Heng, Radhika R. Josi, Ankur Khanna, and Damir B. Khismatullin. 2026. "Low-Density Lipoproteins Induce a Pro-Inflammatory, Chemotactic Mox-like Phenotype in THP-1-Derived Human Macrophages" Cells 15, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010055

APA StyleYu, H., Josi, R. R., Khanna, A., & Khismatullin, D. B. (2026). Low-Density Lipoproteins Induce a Pro-Inflammatory, Chemotactic Mox-like Phenotype in THP-1-Derived Human Macrophages. Cells, 15(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010055