Oncolytic Virotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanistic Insights, Enhancer Strategies, and Translational Combinations

Highlights

- Standalone oncolytic viruses induce tumor-selective lysis and remodel the colorectal tumor microenvironment.

- Combinations with immune checkpoint inhibitors consistently enhance tumor control in colorectal cancer.

- Enhancer tools further improve viral delivery, selectivity, efficacy, and evasion of antiviral immune responses.

- Synergy with immune checkpoint inhibitors offers an opportunity to overcome therapeutic resistance in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Standalone Oncolytic Viruses

3.2. Oncolytic Virus Combination Therapies

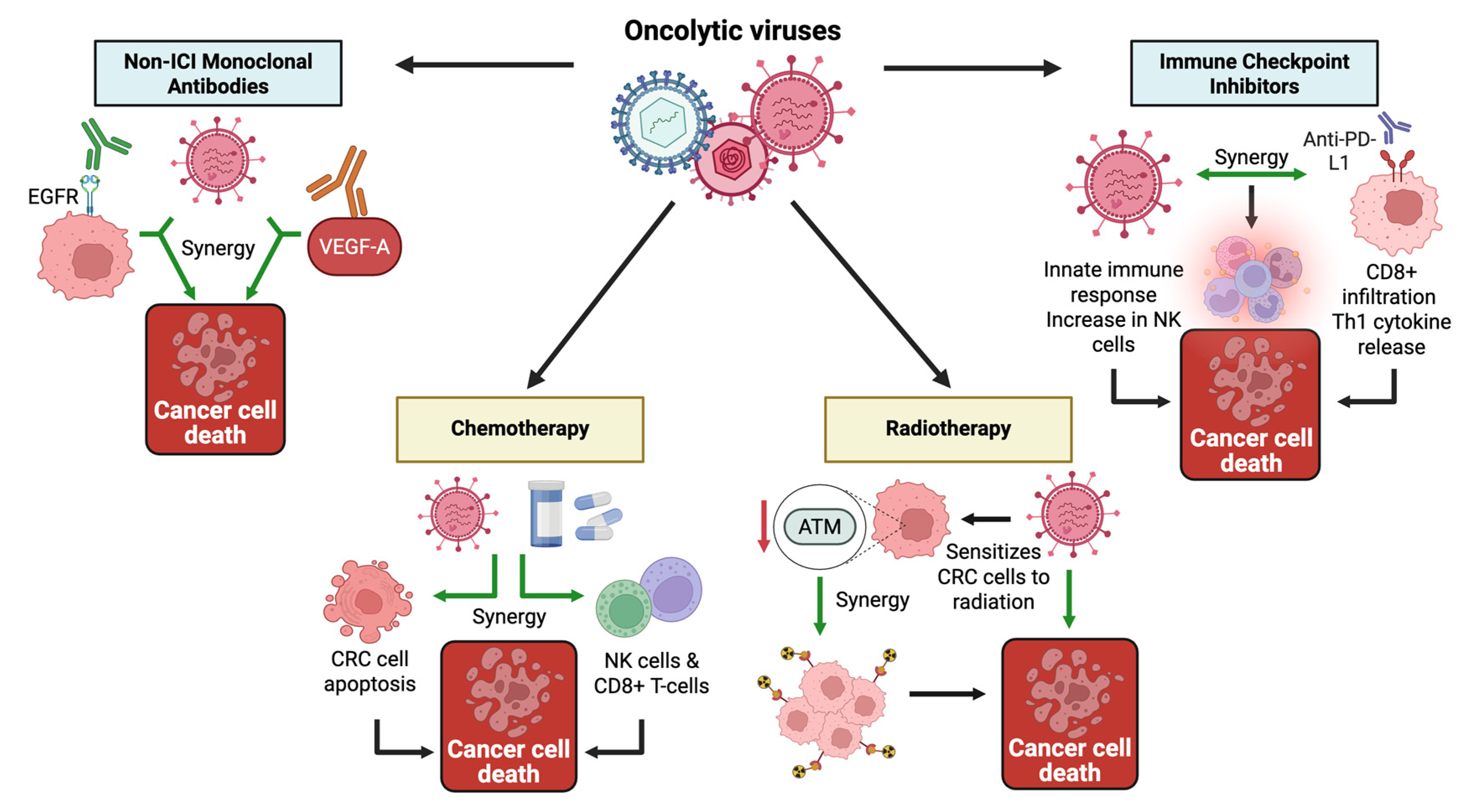

3.2.1. Combinations with Immunotherapy

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Monoclonal Antibodies (Other Than ICIs)

3.2.2. Other Synergistic Combinations

Chemotherapy

Radiotherapy and Radiolabeled Strategies

Novel Combination Strategies

| (a) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Family | Virus | Study Type | Model/Cell Type | Direct Oncolysis | Immune Activation | Angio Targeting | Other Mechanism | Enhancer Used | Enhancer Type | Citation |

| Adenoviridae | OA@CuMnCs (H101 oncolytic Ad-5 with Cu/Mn shell) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC cell line; CT26 syngeneic tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↓ PD-L1; ↑ IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α; ↑ CD4+/CD8+ infiltration; ↑ DC maturation) | ✖ | STING activation; ICD | Copper–manganese biomineral coating | Immune evasion and hypoxia relief | [88] |

| Oncolytic virus Ad·(ST13)·CEA·E1A(Δ24) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Mitochondrial apoptosis via caspase 9/3 | Gene-armed OV (ST13 tumor suppressor) | Genetic engineering | [89] | |

| rAd.DCN.GM (decorin + GM-CSF) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines; CT26 syngeneic tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+ T cells, perforin/granzyme B; ↑ DCs) | ✓ | N/A | Decorin + GM-CSF gene arming | Cytokine arming/genetic engineering | [90] | |

| Wnt-targeted NTR-armed adenovirus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human CRC lines; SW620 xenografts in NMRI nu/nu mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ | Bystander killing effect | Nitroreductase (NTR) | Tumor targeting/genetic engineering | [57] | |

| Oncolytic Adenovirus (CRAd5/F11) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | CRC cell lines; SW620 xenografts in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ | Tumor-specific tropism via MenSCs | Menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MenSCs) | Tumor targeting/immune evasion/enhanced delivery | [91] | |

| ZD55-VEGI-251 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 human CRC line; SW620 xenografts in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ (VEGI-mediated antiangiogenesis) | mitochondria-mediated apoptosis via caspase-9/-3 | Secreted isoform of VEGI (VEGI-251) | Genetic arming/tumor targeting | [92] | |

| dl1520 (ONYX-015) | Preclinical (In vitro) | 9 Human CRC and normal cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Tumor selectivity via differential viral replication at fever temp | Febrile temperature (39.5 °C) | Tumor targeting/Safety | [93] | |

| rAd.mDCN.mCD40L | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines; 1 murine CRC line (CT26); CT26 murine CRC tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+, CD4+ memory, Th1 cytokines, ↓ Th2) | ✖ | Decorin inhibited TGF-β signaling → ↓ immune suppression; ↓ Met expression in CRC cells (anti-metastatic) | Decorin (mDCN) and CD40 Ligand (mCD40L) | Genetic engineering/Immune activator | [94] | |

| Oncolytic adenoviruses (ADVNE and ADVPPE) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 murine CRC lines; CT26 and MC38 tumors in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (Pyroptosis → HMGB1 release → TLR4 activation → ↑ M1 polarization) | ✖ | Tumor microenvironment modulation via macrophage reprogramming; overcoming T cell suppression | NE and PPE | Immune activators/Tumor targeting | [95] | |

| Ad5-D24-RGD | Preclinical (in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ | N/A | Macrophage Metalloelastase (MME) | Tumor Penetration | [96] | |

| Herpesviridae | NV1042 (IL-12-secreting oncolytic HSV-1) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC line; CT26 syngeneic flank tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (IL-12 → ↑ T/NK cytotoxicity; IFN-γ induction) | ✖ | N/A | IL-12 cytokine arming | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [97] |

| G207 (HSV with CEA-driven UL39) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | Human CRC lines; CRC xenografts in athymic nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | CEA enhancer-promoter (CEA E-P) | Tumor targeting/Viral Replication | [98] | |

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 (VG22401) | Preclinical (in vivo and in vitro) | 1 murine CRC line and 2 human CRC cell lines; CT26-HER2 syngeneic CRC model in Balb/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (anti-HER2 T cells and antibodies; ADCC, CDC; ↑ IFNγ+ splenocytes) | ✖ | N/A | Cytokine payload of IL-12, IL-15, and IL-15Ra | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [99] | |

| HSV1716 | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 Human CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | Ing4 (Inhibitor of Growth 4) | Virus replication/genetic engineering | [100] | |

| HSV-1 | Preclinical (in vitro) | 2 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD4+, CD8+ and macrophages; ↑ IFN-γ release and PBMC proliferation) | ✖ | N/A | IL-12 gene insertion | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [101] | |

| G207 (HSV-1) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC line; CT26 tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | 10xHRE upstream of UL39 | Multimerized VEGF-derived hypoxia-responsive enhancer | [102] | |

| oncolytic SS2 | Preclinical (in vivo and in vitro) | Human CRC line with CD133+ subpopulation; CRC xenografts in athymic nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | CD133 promoter | Tumor targeting | [103] | |

| Paramyxoviridae | NDV (rNDV-mOX40L) | Preclinical (In vitro and in vivo) | One murine CRC line; CT26 flank tumors in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD4+, CD8+ and OX40+ T lymphocytes; ↑ IFN-γ and CTL activity) | ✖ | N/A | OX40L (OX40 ligand) | Immune activator | [104] |

| NDV (S519G mutant) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 human CRC cell line; xenografts in nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | S519G mutation in Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase | Genetic engineering | [105] | |

| Picornaviridae | Coxsackievirus B3 (Strain H3) | Preclinical (in vitro and vivo) | One human CRC line; DLD-1 xenografts in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | miRNA-target site engineering (miR-375 and miR-1) | Tumor targeting | [106] |

| Coxsackievirus A21 (CVA21) | Preclinical (in vivo) | murine colorectal cancer cells | ✓ | ✓ (↑ IFN-γ, ↓ IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β; ↑ splenocyte proliferation) | ✖ | N/A | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Enhanced delivery | [107] | |

| CVB3 (Nancy, 31-1-93,H3, and PD) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 9 human CRC lines; DLD1 xenograft model | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | N- and 6-O-sulfated Heparan Sulfate | Tumor Targeting | [108] | |

| Poxviridae | VG9-IL-24 (IL-24-armed vaccinia) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 CRC cell lines; CT26 syngeneic tumors and HCT116 xenografts | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CTL activity, ↑ IFN-γ/IL-6/TNF-α, tumor-specific memory) | ✓ | G2/M arrest; apoptosis via PKR-p38/JNK; bystander effect | IL-24 cytokine arming | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [109] |

| TPV/Δ2L/Δ66R/FliC (tanapoxvirus expressing flagellin) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 human CRC line; HCT116 xenografts | ✓ | ✓ (↑ lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration) | ✖ | FliC→TLR5-driven innate activation and necrosis | FliC (bacterial flagellin) | Innate immune activator (TLR5 agonist) | [110] | |

| vvDD-mIL2 (vaccinia expressing membrane-tethered IL-2) | Preclinical (in vivo; bilateral flank) | MC38-luc murine CRC line; MC38-luc syngeneic tumors in C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+ TILs; ↑ IFN-γ; ↑ CD11c+; abscopal immunity) | ✓ | N/A | Membrane-tethered IL-2 | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [70] | |

| Vaccinia virus (VVLΔTKΔN1L-mIL-21) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 murine CRC cell lines; CMT93 and CT26 syngeneic models in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (CD8+ T cell killing; memory formation; ↑ IFN-γ; IL-21 modulation) | ✓ (IL-21 reduces VEGFR1 and TIE1 in endothelial cells) | N/A | Virus-encoded IL-21 | Localized immunomodulator/genetic engineering | [111] | |

| vvTRAIL (TRAIL-armed vaccinia) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines; 1 murine CRC line; HCT116 and MC38 peritoneal carcinomatosis models in nude and C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | TRAIL→DR4/DR5 extrinsic apoptosis; ↑ cleaved caspase-8/PARP; bystander kill; | TRAIL gene arming | Death ligand/apoptosis inducer | [71] | |

| Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus-Luc@Ce6 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | Human and murine colon cancer cell lines; CT26 syngeneic tumors in male BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ T cells, ↑ DCs, ↓ Tregs; induces ICD and boosts innate + adaptive immunity) | ✓ | N/A | Engineered to express firefly luciferase and surface-loaded with Chlorin e6. | Self-activating photodynamic enhancer | [112] | |

| PLTM-ICG-OVV (PIOVV) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | Murine colon cancer cell lines; syngeneic tumors in male BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (Enhanced ROS accumulation) | ✓ | N/A | Indocyanine green (ICG), platelet membrane (PLTM) encapsulation | Photosensitizer/tumor targeting/enhanced delivery/immune evasion | [113] | |

| VVL15 | Preclinical (in vivo) | CT26 murine colorectal cancer cell line | ✓ | ✓ (↓ Macrophage-mediated clearance) | ✖ | N/A | PI3Kδ inhibitor (IC87114 or Idelalisib | Immune evasion | [114] | |

| GLV-1h153 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human colorectal cancer cell lines; athymic nude mice (xenografts). | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | hNIS (human sodium iodide symporter) | Enhanced Delivery and imaging enhancement | [115] | |

| Recombinant OVV | Preclinical (in vitro) | 7 Human colorectal cancer cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | lncRNA UCA1 | Virus Spread | [116] | |

| Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 7 human and murine CRC cell lines; xenograft mouse models | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD4+/CD8+; ↑ perforin and granzyme B cytotoxicity; ↑ cytokines) | ✖ | Bystander killing effect | Genetic modification to express bispecific T-cell engagers (TCEs) | Immune activation | [117] | |

| oncoVV-AVL | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC cell lines; xenograft tumors in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | AVL (marine C-type lectin) | Tumor targeting | [118] | |

| Reoviridae | Oncolytic Reovirus | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 murine CRC cell line and mouse-derived MSCs; BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Apoptosis via RAS-caspase pathway; ↑ Secretome-mediated cytotoxicity | Infected MSC-derived secretome | Enhanced delivery | [119] |

| Reovirus (ReoT3D) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 murine CRC line; 1 murine fibroblast line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Apoptosis; ↑ Cell Cycle Arrest (G0/G1, G2/M) | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs) | Enhanced delivery | [120] | |

| Reovirus (T3D) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 murine CRC line; 1 murine fibroblast line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Apoptosis (Annexin V/PI flow cytometry) | low-intensity ultrasound | Enhanced delivery | [121] | |

| Reovirus type 3 Dearing strain (RC402) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 2 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) | Systemic Immune activator | [122] | |

| (b) | ||||||||||

| Virus Family | Virus | Trial Phase | Enhancer | Trial Status | Patient Population | Delivery Route | Adverse Events | Outcomes/Endpoints | Quantitative Information | Citation |

| Herpesviridae | NV1020 (HSV-1) | Phase I | Genetic engineering | Completed | N = 12 mCRC liver-dominant | Single HAI NV1020 | Mild fever/HA/rigors; transient LFT↑ | Safety of HAI NV1020; day-28 tumor response | 1 pt −39%, 1 pt −20%; 7 SD, 3 PD; strong hepatic clearance, minimal systemic virus | [123] |

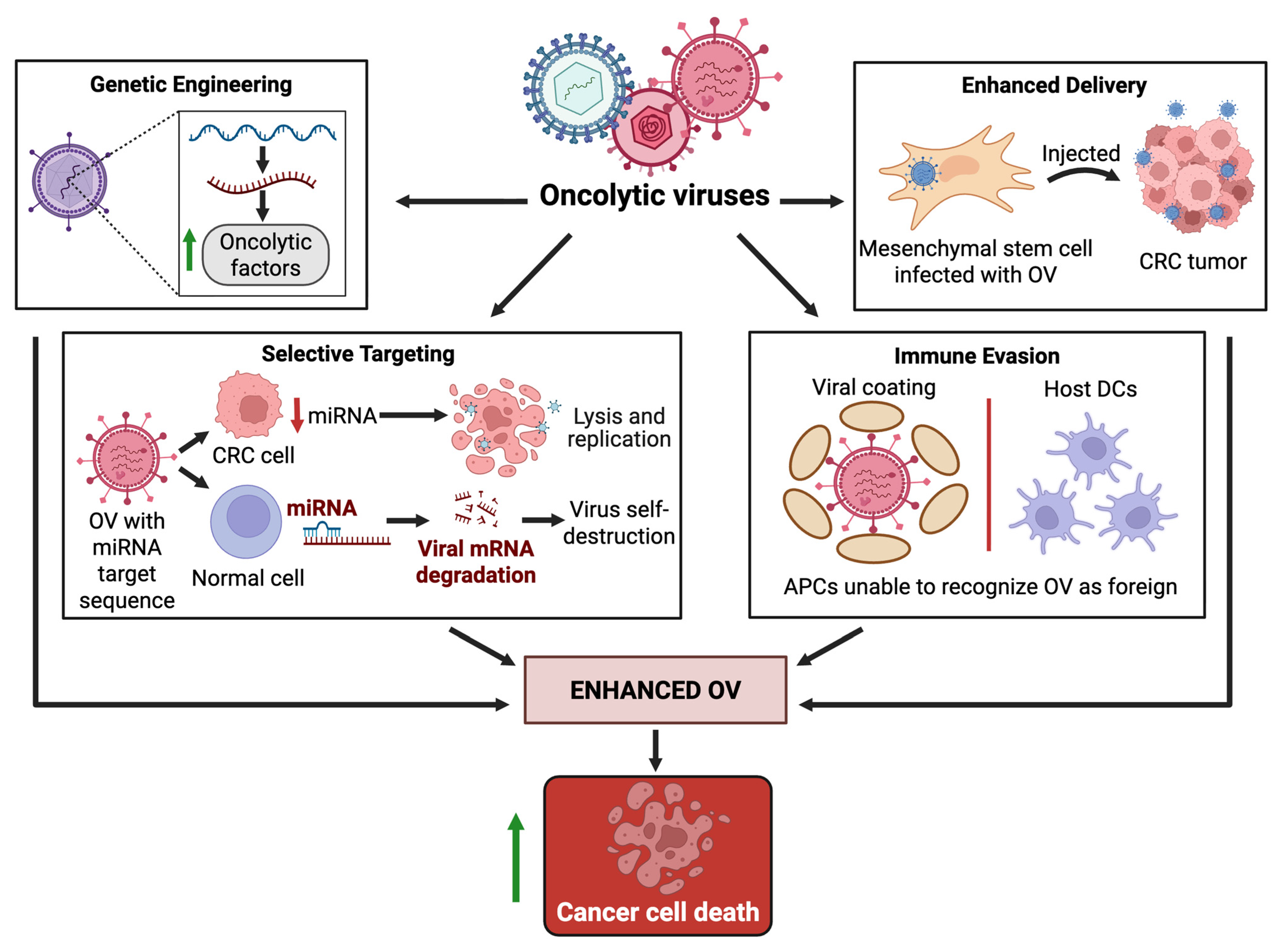

3.3. Enhancers of Oncolytic Virus Therapy

4. Discussion

4.1. Biomarkers for Patient Selection and Response Monitoring in OV Therapy

4.2. Practical Challenges of OV Delivery in Metastatic CRC

4.3. Preclinical Modeling Barriers to Translating OV Therapy in CRC

4.4. Safety and Toxicity Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

References

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Jiang, C.; Morgan, E.; Zahwe, M.; Cao, Y.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer incidence trends in younger versus older adults: An analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Han, S.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, W. Global burden of colon and rectal cancer and attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.R.; Lieu, C.H. Anti-EGFR Therapy for Left-Sided RAS Wild-type Colorectal Cancer-PARADIGM Shift. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, V.; Sandhu, A.; Rawat, K.; Sharma, A.; Saha, L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.-X.; Gao, D.; Shao, Z.-Z.; Chen, L.; Ding, W.-J.; Yu, Q.-F. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: Causes and treatment targets of drug resistance in colorectal cancer (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.-X.; Zhao, R.-X.; Gao, C.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, J. Recent advances and challenges in colorectal cancer: From molecular research to treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, S.; Enta, A.; Maruya, Y.; Inomata, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Mine, H.; Takagi, H.; Ozaki, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Inoue, T.; et al. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling and Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: From Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer to Other Cancers. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, L.; Lemahieu, J.; Palmans, S.; Govaere, O.; Tousseyn, T.; Van Cutsem, E.; Prenen, H.; Tejpar, S.; Spaepen, M.; Matthijs, G.; et al. Microsatellite instable vs stable colon carcinomas: Analysis of tumour heterogeneity, inflammation and angiogenesis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Zhou, W. Immunotherapy in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer: Strategies to overcome resistance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 212, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, Z.; Chiocca, E.A.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Yu, J. The emerging field of oncolytic virus-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hui, P.; Du, X.; Su, X. Updates to the antitumor mechanism of oncolytic virus. Thorac. Cancer 2019, 10, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePeaux, K.; Delgoffe, G.M. Integrating innate and adaptive immunity in oncolytic virus therapy. Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.J.; Barber, G.N. Oncolytic Viruses as Antigen-Agnostic Cancer Vaccines. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, K. Immunogenic cell death-based oncolytic virus therapy: A sharp sword of tumor immunotherapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 981, 176913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretwell, E.C.; Houldsworth, A. Oncolytic Virus Therapy in a New Era of Immunotherapy, Enhanced by Combination with Existing Anticancer Therapies: Turn up the Heat! J. Cancer 2025, 16, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos de Matos, A.; Franco, L.S.; McFadden, G. Oncolytic Viruses and the Immune System: The Dynamic Duo. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 17, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysome, J.; Lemoine, N.; Wang, Y. Update on oncolytic viral therapy–targeting angiogenesis. OTT 2013, 6, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Liang, T. Oncolytic virotherapy: Basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jou, T.H.-T.; Hsin, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Ye, J.; Yin, H.; Xing, Y. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC): A Review of the Recent Advances in Cancer Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, M.; Guo, J.; He, P.; Zhou, D. Recent advances of oncolytic virus in cancer therapy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge, C.; Xie, C.; Myojin, Y.; Coffman, K.; Hrones, D.M.; Wang, S.; Hernandez, J.M.; Wood, B.J.; Levy, E.B.; Juburi, I.; et al. Phase I/II study of PexaVec in combination with immune checkpoint inhibition in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Pan, Y.; He, B.; Deng, Q.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, T.; Ying, H.; Wang, F.; et al. Gene therapy for human colorectal cancer cell lines with recombinant adenovirus 5 based on loss of the insulin-like growth factor 2 imprinting. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nie, Z.-L.; Pan, Y.-Q.; He, B.-S.; Gu, L.; Chen, L.-P.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Gao, T.-Y.; Song, G.-Q.; Hoffman, A.R.; et al. Gene therapy for colorectal cancer by an oncolytic adenovirus that targets loss of the insulin-like growth factor 2 imprinting system. Mol. Cancer 2012, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.-L.; Lei, J.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Dyer, A.; Fisher, K.D.; Seymour, L.W. Group B adenovirus enadenotucirev infects polarised colorectal cancer cells efficiently from the basolateral surface expected to be encountered during intravenous delivery to treat disseminated cancer. Virology 2017, 505, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhang, F.; Diao, Y.; Zan, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. The Effects of Oncolytic Pseudorabies Virus Vaccine Strain Inhibited the Growth of Colorectal Cancer HCT-8 Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Animals 2022, 12, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhao, C.; Han, J.; Li, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Xiao, R.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Y. Antitumor effects of oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 2 against colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2017, 13, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, B.; Hu, X.; Zou, L.; Liang, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, S. Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Can Effectively Inhibit Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis by Modulating the Immune Status in the Tumor Microenvironment and Inducing Specific Antitumor Immunity. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021, 32, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberhumer, G.R.; Zakian, K.; Malhotra, S.; Brader, P.; Gönen, M.; Koutcher, J.; Fong, Y. Relationship between 31P metabolites and oncolytic viral therapy sensitivity in human colorectal cancer xenografts. Br. J. Surg. 2009, 96, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooby, D.A.; Carew, J.F.; Halterman, M.W.; Mack, J.E.; Bertino, J.R.; Blumgart, L.H.; Federoff, H.J.; Fong, Y. Oncolytic viral therapy for human colorectal cancer and liver metastases using a multi-mutated herpes simplex virus type-1 (G207). FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagai, Y.; Fujiyuki, T.; Yoneda, M.; Shoji, K.; Furukawa, Y.; Sato, H.; Kai, C. Oncolytic Activity of a Recombinant Measles Virus, Blind to Signaling Lymphocyte Activation Molecule, Against Colorectal Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudi, R.; Mohammadi, A.; Morovati, S.; Heidari, A.A.; Asad-Sangabi, M. Induction of apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells by matrix protein of PPR virus as a novel anti-cancer agent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 245, 125536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisgerault, N.; Guillerme, J.-B.; Pouliquen, D.; Mesel-Lemoine, M.; Achard, C.; Combredet, C.; Fonteneau, J.-F.; Tangy, F.; Grégoire, M. Natural oncolytic activity of live-attenuated measles virus against human lung and colorectal adenocarcinomas. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 387362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, S.-L.; Tan, W.-S.; Yusoff, K.; Shafee, N. Plaque formation by a velogenic Newcastle disease virus in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Acta Virol. 2012, 56, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Gabere, M.; Taylor, M.A.; Simoes, C.C.; Dumbauld, C.; Barro, O.; Tesfay, M.Z.; Graham, A.L.; Ferdous, K.U.; Savenka, A.V.; et al. Repurposing live attenuated trivalent MMR vaccine as cost-effective cancer immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1042250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelsson, S.; Jonsson, N.; Gullberg, M.; Lindberg, A.M. Cytolytic replication of echoviruses in colon cancer cell lines. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, R.; Long, M.; Li, W.; Xiao, B.; Deng, H.; Weng, K.; Gong, D.; Liu, F.; Luo, S.; et al. Identification of in vitro and in vivo oncolytic effect in colorectal cancer cells by Orf virus strain NA1/11. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrig, K.; Kilinc, M.O.; Chen, N.G.; Stritzker, J.; Buckel, L.; Zhang, Q.; Szalay, A.A. Growth inhibition of different human colorectal cancer xenografts after a single intravenous injection of oncolytic vaccinia virus GLV-1h68. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.P.; Warner, S.G.; Kim, S.-I.; Chaurasiya, S.; Lu, J.; Choi, A.H.; Park, A.K.; Woo, Y.; Fong, Y.; Chen, N.G. A Novel Oncolytic Chimeric Orthopoxvirus Encoding Luciferase Enables Real-Time View of Colorectal Cancer Cell Infection. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2018, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, R.A.; Scott, K.J.; Fraser, S.; Errington-Mais, F.; Pandha, H.; Coffey, M.; Selby, P.; Cook, G.P.; Vile, R.; Harrington, K.J.; et al. Cytotoxic and immune-mediated killing of human colorectal cancer by reovirus-loaded blood and liver mononuclear cells. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiffry, J.; Thavornwatanayong, T.; Rao, D.; Fogel, E.J.; Saytoo, D.; Nahata, R.; Guzik, H.; Chaudhary, I.; Augustine, T.; Goel, S.; et al. Oncolytic Reovirus (pelareorep) Induces Autophagy in KRAS-mutated Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, Z.; Tabarraei, A.; Moradi, A.; Kalani, M.R. M51R and Delta-M51 matrix protein of the vesicular stomatitis virus induce apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 3371–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.H., 4th; Ahmed, M.; Northrup, S.A.; Willingham, M.; Lyles, D.S. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a treatment for colorectal cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, K.; Ebert, O.; Woo, S.L.C. Treatment of multi-focal colorectal carcinoma metastatic to the liver of immune-competent and syngeneic rats by hepatic artery infusion of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Breitbach, C.J.; Lee, J.; Park, J.O.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K.; Moon, A.; Mun, J.-H.; Sommermann, E.M.; Maruri Avidal, L.; et al. Phase 1b Trial of Biweekly Intravenous Pexa-Vec (JX-594), an Oncolytic and Immunotherapeutic Vaccinia Virus in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, A.; West, E.J.; Carmichael, J.; Scott, K.J.; Turnbull, S.; Kuszlewicz, B.; Dave, R.V.; Peckham-Cooper, A.; Tidswell, E.; Kingston, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Intravenous Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Therapy Promotes Anticancer Immunity in Patients. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022, 10, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakrama, R.; Fogel, E.; Chandy, C.; Augustine, T.; Coffey, M.; Tesfa, L.; Goel, S.; Maitra, R. Immune characterization of metastatic colorectal cancer patients post reovirus administration. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; Holmes, T.D.; Wetherill, L.F.; Black, E.V.I.; Wilson, E.B.; Phillips, S.L.; Scott, G.B.; Adair, R.A.; Dave, R.; Scott, K.J.; et al. Controlled infection with a therapeutic virus defines the activation kinetics of human natural killer cells in vivo. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2015, 180, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Qin, Y.; Ying, C.; Ma, B.; Wang, B.; Long, F.; Wang, R.; Fang, L.; Wang, Y. Combination of oncolytic adenovirus and luteolin exerts synergistic antitumor effects in colorectal cancer cells and a mouse model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 9375–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment via Oncolytic Viruses and CSF-1R Inhibition Synergistically Enhances Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kuroda, S.; Yamasaki, Y.; Yano, S.; Ouchi, M.; Tazawa, H.; Uno, F.; Kagawa, S.; et al. In vivo biological purging for lymph node metastasis of human colorectal cancer by telomerase-specific oncolytic virotherapy. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. A Case Report of Pathologically Complete Response of a Huge Lymph Node Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer After Treatment with Intratumoral Oncolytic Virus H101 and Capecitabine. Immunotargets Ther. 2024, 13, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, M.; Yuan, M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Wu, X.; Hui, B.; Yang, Y.; Wei, B.; et al. CXCL10-armed oncolytic adenovirus promotes tumor-infiltrating T-cell chemotaxis to enhance anti-PD-1 therapy. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2118210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Qu, W.; Mao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Jia, L.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, X. Antitumor effects of oncolytic adenovirus armed with Drosophila melanogaster deoxyribonucleoside kinase in colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 27, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakamura, N.; Sato-Dahlman, M.; Travis, E.; Jacobsen, K.; Yamamoto, M. CDX2 Promoter-Controlled Oncolytic Adenovirus Suppresses Tumor Growth and Liver Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2025, 116, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashev, A.N.; Fuerer, C.; Chen, M.-J.; Searle, P.; Iggo, R. Late expression of nitroreductase in an oncolytic adenovirus sensitizes colon cancer cells to the prodrug CB1954. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005, 16, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Dai, S.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Decorin-armed oncolytic adenovirus promotes natural killers (NKs) activation and infiltration to enhance NK therapy in CRC model. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-T.; Wu, M.-H.; Chen, M.-J.; Lin, S.-P.; Yen, Y.-T.; Hung, S.-C. Combination of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Delivered Oncolytic Virus with Prodrug Activation Increases Efficacy and Safety of Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ichinose, T.; Naoe, Y.; Matsumura, S.; Villalobos, I.B.; Eissa, I.R.; Yamada, S.; Miyajima, N.; Morimoto, D.; Mukoyama, N.; et al. Combination of Cetuximab and Oncolytic Virus Canerpaturev Synergistically Inhibits Human Colorectal Cancer Growth. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2019, 13, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayes, N.; Vito, A.; Salem, O.; Workenhe, S.T.; Wan, Y.; Mossman, K. A Combination of Chemotherapy and Oncolytic Virotherapy Sensitizes Colorectal Adenocarcinoma to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in a cDC1-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Fang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, L. Oncolytic virus oHSV2 combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors exert antitumor activity by mediating CD4 + T and CD8 + T cell infiltration in the lymphoma tumor microenvironment. Autoimmunity 2023, 56, 2259126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Jing, O.; Yi, H.; et al. β-Adrenergic Receptor Inhibitor and Oncolytic Herpesvirus Combination Therapy Shows Enhanced Antitumoral and Antiangiogenic Effects on Colorectal Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 735278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvarchinghaleh, H.E.; Jalili, C.; Nasta, M.Z.; Mokhles, F.; Afrasiab, E.; Babaei, F. Synergistic effects of Bacillus coagulans and Newcastle disease virus on human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell proliferation. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2024, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani Alvanegh, A.; Mirzaei Nodooshan, M.; Dorostkar, R.; Ranjbar, R.; Jalali Kondori, B.; Shahriary, A.; Parastouei, K.; Vazifedust, S.; Afrasiab, E.; Esmaeili Gouvarchinghaleh, H. Antiproliferative effects of mesenchymal stem cells carrying Newcastle disease virus and Lactobacillus Casei extract on CT26 Cell line: Synergistic effects in cancer therapy. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2023, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ogata, H.; Takishima, Y.; Miyamoto, S.; Inoue, H.; Kuroda, M.; Yamada, K.; Hijikata, Y.; Murahashi, M.; Shimizu, H.; et al. A Novel Combination Therapy for Human Oxaliplatin-resistant Colorectal Cancer Using Oxaliplatin and Coxsackievirus A11. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 6121–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, M.; Geisler, A.; Hinze, L.; Elsner, L.; Dieringer, B.; Beling, A.; Kurreck, J.; Fechner, H. Combination of FOLFOXIRI Drugs with Oncolytic Coxsackie B3 Virus PD-H Synergistically Induces Oncolysis in the Refractory Colorectal Cancer Cell Line Colo320. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Grein, J.; Selman, M.; Annamalai, L.; Yearley, J.H.; Blumenschein, W.M.; Sadekova, S.; Chackerian, A.A.; Phan, U.; Wong, J.C. Oncolytic virus V937 in combination with PD-1 blockade therapy to target immunologically quiescent liver and colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2024, 32, 200807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottolino-Perry, K.; Mealiea, D.; Sellers, C.; Acuna, S.A.; Angarita, F.A.; Okamoto, L.; Scollard, D.; Ginj, M.; Reilly, R.; McCart, J.A. Vaccinia virus and peptide-receptor radiotherapy synergize to improve treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2023, 29, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Dai, E.; Liu, Z.; Ma, C.; Guo, Z.S.; Bartlett, D.L. In Situ Therapeutic Cancer Vaccination with an Oncolytic Virus Expressing Membrane-Tethered IL-2. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 17, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziauddin, M.F.; Guo, Z.S.; O’Malley, M.E.; Austin, F.; Popovic, P.J.; Kavanagh, M.A.; Li, J.; Sathaiah, M.; Thirunavukarasu, P.; Fang, B.; et al. TRAIL gene-armed oncolytic poxvirus and oxaliplatin can work synergistically against colorectal cancer. Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, L.; Guo, Z.S.; Liu, Z.; Ravindranathan, R.; Urban, J.A.; Sathaiah, M.; Magge, D.; Kalinski, P.; Bartlett, D.L. Modulation of chemokines in the tumor microenvironment enhances oncolytic virotherapy for colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 22174–22185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottolino-Perry, K.; Acuna, S.A.; Angarita, F.A.; Sellers, C.; Zerhouni, S.; Tang, N.; McCart, J.A. Oncolytic vaccinia virus synergizes with irinotecan in colorectal cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, J.J.; Sampath, P.; Hou, W.; Thorne, S.H. Defining Effective Combinations of Immune Checkpoint Blockade and Oncolytic Virotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5543–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Soleimanjahi, H.; Soleimani, M.; Arefian, E. The synergistic anticancer effects of ReoT3D, CPT-11, and BBI608 on murine colorectal cancer cells. Daru 2020, 28, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaykevich, A.; Chae, D.; Silverman, I.; Goel, S.; Maitra, R. Modulating autophagy in KRAS mutant colorectal cancer using combination of oncolytic reovirus and carbamazepine. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, N.; Kubota, E.; Mori, Y.; Aoyama, M.; Tanaka, M.; Shimura, T.; Tanida, S.; Johnston, R.N.; Kataoka, H. Reovirus combined with a STING agonist enhances anti-tumor immunity in a mouse model of colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 3593–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhamipour, M.; Soleimanjahi, H.; Abdoli, A.; Sharifi, N.; Karimi, H.; Soleyman Jahi, S.; Kvistad, R. Combination Therapy with Secretome of Reovirus-Infected Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Metformin Improves Anticancer Effects of Irinotecan on Colorectal Cancer Cells in vitro. Intervirology 2025, 68, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smakman, N.; van den Wollenberg, D.J.M.; Elias, S.G.; Sasazuki, T.; Shirasawa, S.; Hoeben, R.C.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.M.; Kranenburg, O. KRAS(D13) Promotes apoptosis of human colorectal tumor cells by ReovirusT3D and oxaliplatin but not by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5403–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Feng, H.; Xi, Z.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zheng, J.; Lyu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. Targeting TBK1 potentiates oncolytic virotherapy via amplifying ICAM1-mediated NK cell immunity in chemo-resistant colorectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.; Harb, W.; Mahadevan, D.; Babiker, H.; Berlin, J.; Lillie, T.; Krige, D.; Carter, J.; Cox, C.; Patel, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the tumor-selective adenovirus enadenotucirev, in combination with nivolumab, in patients with advanced/metastatic epithelial cancer: A phase I clinical trial (SPICE). J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, T.R.; Freeman, S.; Post, L.; McCormick, F.; Sze, D.Y. Effects of Onyx-015 among metastatic colorectal cancer patients that have failed prior treatment with 5-FU/leucovorin. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, Y.; Kim, T.; Bhargava, A.; Schwartz, L.; Brown, K.; Brody, L.; Covey, A.; Karrasch, M.; Getrajdman, G.; Mescheder, A.; et al. A herpes oncolytic virus can be delivered via the vasculature to produce biologic changes in human colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, J.R.; Raman, S.S.; Chan, A.; Kalinsky, K.; Baurain, J.-F.; Jimenez, M.M.; Garcia, M.M.; Berger, M.D.; Lauer, U.M.; Khattak, A.; et al. Phase Ib study of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with atezolizumab in patients with triple negative breast cancer and colorectal cancer with liver metastases. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, E.J.; Sadoun, A.; Bendjama, K.; Erbs, P.; Smolenschi, C.; Cassier, P.A.; de Baere, T.; Sainte-Croix, S.; Brandely, M.; Melcher, A.A.; et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial of Intrahepatic Artery Delivery of TG6002 in Combination with Oral 5-Fluorocytosine in Patients with Liver-Dominant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, D.J.; Tang, P.A.; Kennecke, H.; Welch, S.A.; Cripps, M.C.; Asmis, T.; Chalchal, H.; Tomiak, A.; Lim, H.; Ko, Y.-J.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Study of FOLFOX6/Bevacizumab with or Without Pelareorep in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: IND.210, a Canadian Cancer Trials Group Trial. Clin. Color. Cancer 2018, 17, 231–239.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Ocean, A.J.; Parakrama, R.Y.; Ghalib, M.H.; Chaudhary, I.; Shah, U.; Viswanathan, S.; Kharkwal, H.; Coffey, M.; Maitra, R. Elucidation of Pelareorep Pharmacodynamics in A Phase I Trial in Patients with KRAS-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-S.; Ye, L.-Y.; Luo, Y.-X.; Zheng, W.-J.; Si, J.-X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Wang, S.-B.; Zou, H.; Jin, K.-T.; et al. Tumor-targeted delivery of copper-manganese biomineralized oncolytic adenovirus for colorectal cancer immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2024, 179, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xie, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, S.; Chu, L.; Xiao, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Potent and specific antitumor effect for colorectal cancer by CEA and Rb double regulated oncolytic adenovirus harboring ST13 gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Xiao, F.; Bai, Z.; Yao, H.; Ma, X.; et al. An Oncolytic Adenovirus Encoding Decorin and Granulocyte Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor Inhibits Tumor Growth in a Colorectal Tumor Model by Targeting Pro-Tumorigenic Signals and via Immune Activation. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, D.; Li, Y.; Mou, X.; Liu, F.; Xiang, C. Menstrual Blood-Derived Stem Cells as Delivery Vehicles for Oncolytic Adenovirus Virotherapy for Colorectal Cancer. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 882–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Fan, J.K.; Huang, H.L.; Gu, J.F.; Li, L.-Y.; Liu, X.Y. VEGI-armed oncolytic adenovirus inhibits tumor neovascularization and directly induces mitochondria-mediated cancer cell apoptosis. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S.H.; Brooks, G.; Lee, Y.-L.; Au, T.; Eng, L.F.; Reid, T. Effects of febrile temperature on adenoviral infection and replication: Implications for viral therapy of cancer. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Y.; Ning, Y.; Zhu, J.; Feng, P.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, Z.; Ruan, C.; Jin, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Oncolytic adenovirus encoding decorin and CD40 ligand inhibits tumor growth and liver metastasis via immune activation in murine colorectal tumor model. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kong, L.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Gu, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, C. Viral expression of NE/PPE enhances anti-colorectal cancer efficacy of oncolytic adenovirus by promoting TAM M1 polarization to reverse insufficient effector memory/effector CD8(+) T cell infiltration. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavilla-Alonso, S.; Bauer, M.M.T.; Abo-Ramadan, U.; Ristimäki, A.; Halavaara, J.; Desmond, R.A.; Wang, D.; Escutenaire, S.; Ahtiainen, L.; Saksela, K.; et al. Macrophage metalloelastase (MME) as adjuvant for intra-tumoral injection of oncolytic adenovirus and its influence on metastases development. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.J.; Malhotra, S.; Wong, R.J.; Delman, K.; Zager, J.; St-Louis, M.; Johnson, P.; Fong, Y. Interleukin 12 secretion enhances antitumor efficacy of oncolytic herpes simplex viral therapy for colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 2001, 233, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinblatt, M.; Pin, R.H.; Fong, Y. Carcinoembryonic antigen directed herpes viral oncolysis improves selectivity and activity in colorectal cancer. Surgery 2004, 136, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delwar, Z.; Tatsiy, O.; Chouljenko, D.V.; Lee, I.-F.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Bu, L.; Ding, J.; Singh, M.; Murad, Y.M.; et al. Prophylactic Vaccination and Intratumoral Boost with HER2-Expressing Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Induces Robust and Persistent Immune Response against HER2-Positive Tumor Cells. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, J.; Braidwood, L. Expression of inhibitor of growth 4 by HSV1716 improves oncolytic potency and enhances efficacy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi-Najafabadi, N.; Roohvand, F.; Shams Nosrati, M.S.; Teimoori-Toolabi, L.; Azadmanesh, K. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus type-1 expressing IL-12 efficiently replicates and kills human colorectal cancer cells. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 160, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinblatt, M.; Pin, R.H.; Federoff, H.J.; Fong, Y. Utilizing tumor hypoxia to enhance oncolytic viral therapy in colorectal metastases. Ann. Surg. 2004, 239, 892–899; discussion 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terai, K.; Bi, D.; Liu, Z.; Kimura, K.; Sanaat, Z.; Dolatkhah, R.; Soleimani, M.; Jones, C.; Bright, A.; Esfandyari, T.; et al. A Novel Oncolytic Herpes Capable of Cell-Specific Transcriptional Targeting of CD133± Cancer Cells Induces Significant Tumor Regression. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Liu, T.; Jiang, S.; Cao, Y.; Kang, K.; Su, H.; Ren, G.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, W.; Li, D. Oncolytic Newcastle disease virus expressing the co-stimulator OX40L as immunopotentiator for colorectal cancer therapy. Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.-K.; An, Y.H.; Jang, S.H.; Jang, J.-J.; Kim, S.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, J.; Song, J.J.; Jang, H. The artificial amino acid change in the sialic acid-binding domain of the hemagglutinin neuraminidase of newcastle disease virus increases its specificity to HCT 116 colorectal cancer cells and tumor suppression effect. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazini, A.; Dieringer, B.; Pryshliak, M.; Knoch, K.-P.; Heimann, L.; Tolksdorf, B.; Pappritz, K.; El-Shafeey, M.; Solimena, M.; Beling, A.; et al. miR-375- and miR-1-Regulated Coxsackievirus B3 Has No Pancreas and Heart Toxicity But Strong Antitumor Efficiency in Colorectal Carcinomas. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021, 32, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbalaee, R.; Mehdizadeh, S.; Ghaleh, H.E.G.; Izadi, M.; Kondori, B.J.; Dorostkar, R.; Hosseini, S.M. The Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Loaded with Oncolytic Coxsackievirus A21 on Mouse Models of Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2024, 24, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazini, A.; Pryshliak, M.; Brückner, V.; Klingel, K.; Sauter, M.; Pinkert, S.; Kurreck, J.; Fechner, H. Heparan Sulfate Binding Coxsackievirus B3 Strain PD: A Novel Avirulent Oncolytic Agent Against Human Colorectal Carcinoma. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yang, X.; Fan, J.; Ding, Y.; Peng, Y.; Xu, D.; Huang, B.; Hu, Z. IL-24-Armed Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Exerts Potent Antitumor Effects via Multiple Pathways in Colorectal Cancer. Oncol. Res. 2021, 28, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S.J.; El-Aswad, M.; Kurban, E.; Jeng, D.; Tripp, B.C.; Nutting, C.; Eversole, R.; Mackenzie, C.; Essani, K. Oncolytic tanapoxvirus expressing FliC causes regression of human colorectal cancer xenografts in nude mice. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, H.; Yan, W.; Chu, Y.; Chard Dunmall, L.S.; Wang, Y. A novel vaccinia virus enhances anti-tumor efficacy and promotes a long-term anti-tumor response in a murine model of colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2021, 20, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.-Y.; Li, Y.-S.; Ge, T.; Liu, L.-C.; Si, J.-X.; Yang, X.; Fan, W.-J.; Liu, X.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Wang, J.-W.; et al. Engineered Luminescent Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Activation of Photodynamic-Immune Combination Therapy for Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2304136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Ji, L.; Si, J.; Yang, X.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ye, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ge, T.; et al. Platelet membrane-coated oncolytic vaccinia virus with indocyanine green for the second near-infrared imaging guided multi-modal therapy of colorectal cancer. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2024, 671, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.S.; Chard Dunmall, L.S.; Gangeswaran, R.; Marelli, G.; Tysome, J.R.; Burns, E.; Whitehead, M.A.; Aksoy, E.; Alusi, G.; Hiley, C.; et al. Transient Inhibition of PI3Kδ Enhances the Therapeutic Effect of Intravenous Delivery of Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveno, C.; Mojica, K.; Ady, J.W.; Thorek, D.L.J.; Longo, V.; Belin, L.J.; Gholami, S.; Johnsen, C.; Zanzonico, P.; Chen, N.; et al. Gene therapy using therapeutic and diagnostic recombinant oncolytic vaccinia virus GLV-1h153 for management of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Surgery 2015, 157, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horita, K.; Kurosaki, H.; Nakatake, M.; Ito, M.; Kono, H.; Nakamura, T. Long noncoding RNA UCA1 enhances sensitivity to oncolytic vaccinia virus by sponging miR-18a/miR-182 and modulating the Cdc42/filopodia axis in colorectal cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, M.J.F.; Taha, Z.; Janssen, T.J.A.; Petryk, J.; Boulton, S.; Alluqmani, N.; Jirovec, A.; Kassas, O.; Khan, S.T.; Vallati, S.; et al. Oncolytic virus driven T-cell-based combination immunotherapy platform for colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1029269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Ye, T.; Li, G. Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus Expressing Aphrocallistes vastus Lectin as a Cancer Therapeutic Agent. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, A.; Soleimanjahi, H.; Soudi, S.; Habibian, A. Comparison of the Effect of Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Secretome with and without Reovirus in CT26 Cells. Arch. Razi Inst. 2022, 77, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Soleimanjahi, H.; Soleimani, M.; Arefian, E. Mesenchymal stem cells loaded with oncolytic reovirus enhances antitumor activity in mice models of colorectal cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 190, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, N.; Soleimanjahi, H.; Mokhtari-Dizaji, M.; Banijamali, R.S.; Elhamipour, M.; Karimi, H. Low-Intensity Ultrasound as a Novel Strategy to Improve the Cytotoxic Effect of Oncolytic Reovirus on Colorectal Cancer Model Cells. Intervirology 2022, 65, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, K.; Kubota, E.; Mori, Y.; Nishigaki, R.; Kojima, Y.; Kanno, T.; Sasaki, M.; Fukusada, S.; Sugimura, N.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles as a delivery vehicle of oncolytic reovirus. Life Sci. 2025, 368, 123489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemeny, N.; Brown, K.; Covey, A.; Kim, T.; Bhargava, A.; Brody, L.; Guilfoyle, B.; Haag, N.P.; Karrasch, M.; Glasschroeder, B.; et al. Phase I, open-label, dose-escalating study of a genetically engineered herpes simplex virus, NV1020, in subjects with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oronsky, B.; Gastman, B.; Conley, A.P.; Reid, C.; Caroen, S.; Reid, T. Oncolytic Adenoviruses: The Cold War against Cancer Finally Turns Hot. Cancers 2022, 14, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pol, J.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. First oncolytic virus approved for melanoma immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2015, 5, e1115641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CG Oncology Receives Both FDA Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy Designation for Cretostimogene Grenadenorepvec in High-Risk BCG-Unresponsive Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer | CG Oncology. 2023. Available online: https://ir.cgoncology.com/news-releases/news-release-details/cg-oncology-receives-both-fda-fast-track-and-breakthrough/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Soko, G.F.; Kosgei, B.K.; Meena, S.S.; Ng, Y.J.; Liang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Q.; Xu, T.; Hou, X.; Han, R.P.S. Extracellular matrix re-normalization to improve cold tumor penetration by oncolytic viruses. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1535647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Hutzen, B.; Wedekind, M.F.; Cripe, T.P. Oncolytic virus and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade combination therapy. Oncolytic Virother 2018, 7, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilgase, A.; Olmane, E.; Nazarovs, J.; Brokāne, L.; Erdmanis, R.; Rasa, A.; Alberts, P. Multimodality Treatment of a Colorectal Cancer Stage IV Patient with FOLFOX-4, Bevacizumab, Rigvir Oncolytic Virus, and Surgery. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2018, 12, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani, A.; Nasiri, H.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Ahmadian Heris, J.; Mohammadinasab, R.; Sadeghvand, S.; Sadeghi, M.; Valedkarimi, Z.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Shomali, N.; et al. New immunotherapy approaches for colorectal cancer: Focusing on CAR-T cell, BiTE, and oncolytic viruses. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dilley, J.; Arroyo, T.; Ko, D.; Working, P.; Yu, D.-C. Carcinoembryonic antigen-producing cell-specific oncolytic adenovirus, OV798, for colorectal cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- El-Tanani, M.; Rabbani, S.A.; Patni, M.A.; Babiker, R.; Satyam, S.M.; Rangraze, I.R.; Wali, A.F.; El-Tanani, Y.; Porntaveetus, T.; El-Tanani, M.; et al. Efficacy, Safety and Predictive Biomarkers of Oncolytic Virus Therapy in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xia, Q.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Hu, H.; Xia, Q.; Hu, J.; Wang, S. Oncolytic Viruses for the Treatment of Bladder Cancer: Advances, Challenges, and Prospects. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpeut, S.; Noyce, R.S.; Richardson, C.D.; Delpeut, S.; Noyce, R.S.; Richardson, C.D. The Tumor-Associated Marker, PVRL4 (Nectin-4), Is the Epithelial Receptor for Morbilliviruses. Viruses 2014, 6, 2268–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, T.E.; Knol, L.I.; Haas, F.V.; Hartley, A.; Pernickel, S.C.S.; Jády, A.; Finkbeiner, M.S.C.; Achberger, J.; Arelaki, S.; Modic, Ž.; et al. Biomarker screen for efficacy of oncolytic virotherapy in patient-derived pancreatic cancer cultures. eBioMedicine 2024, 105, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minev, B.R.; Lander, E.; Feller, J.F.; Berman, M.; Greenwood, B.M.; Minev, I.; Santidrian, A.F.; Nguyen, D.; Draganov, D.; Killinc, M.O.; et al. First-in-human study of TK-positive oncolytic vaccinia virus delivered by adipose stromal vascular fraction cells. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, J.G.; Workenhe, S.T.; Konda, P.; Gujar, S.; Kroemer, G. Cytokines in oncolytic virotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2020, 56, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, K.; Ou, X.; Xia, Y.; Li, D.; Yang, K.; Ou, X. Systemic Delivery Strategies for Oncolytic Viruses: Advancing Targeted and Efficient Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kabani, A.; Huda, B.; Haddad, J.; Yousuf, M.; Bhurka, F.; Ajaz, F.; Patnaik, R.; Jannati, S.; Banerjee, Y.; Al-Kabani, A.; et al. Exploring Experimental Models of Colorectal Cancer: A Critical Appraisal from 2D Cell Systems to Organoids, Humanized Mouse Avatars, Organ-on-Chip, CRISPR Engineering, and AI-Driven Platforms—Challenges and Opportunities for Translational Precision Oncology. Cancers 2025, 17, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xin, Z.; Wang, K. Patient-Derived Xenograft Model in Colorectal Cancer Basic and Translational Research. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2023, 6, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Li, J.; Li, M.-Y. Patient-Derived Xenograft Model in Cancer: Establishment and Applications. MedComm 2025, 6, e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, N.; Miller, D.M.; Haq, R.; Kaufman, H.L. Clinical landscape of oncolytic virus research in 2020. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e001486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Comparative Safety Profile Assessment of Oncolytic Virus Therapy Based on Clinical Trials | Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. n.d. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1177/2168479017738979 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Onnockx, S.; Baldo, A.; Pauwels, K.; Onnockx, S.; Baldo, A.; Pauwels, K. Oncolytic Viruses: An Inventory of Shedding Data from Clinical Trials and Elements for the Environmental Risk Assessment. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Family | Virus | Study Type | Model/Cell Type | Direct Oncolysis | Immune Activation | Angio Targeting | Other Mechanism | Citation | ||

| Adenoviridae | Recombinant oncolytic adenovirus (Ad312-Early Region 1A) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human cell lines (CRC + normal epithelial) + HT-29 xenograft mouse model | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | [24] | ||

| Ad315-E1A | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human CRC and normal epithelial cell lines; HCT-8 xenograft in athymic nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis induction in Loss of Imprinting (LOI)+ cells | [25] | |||

| EnAd-CMV-GFP | Preclinical (in vitro) | 4 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | [26] | |||

| Herpesviridae | PRV (K61 and HB98 Strain) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 human CRC cell line (HCT-8) | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis via caspase-3 cleavage | [27] | ||

| oHSV2 (Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC cell lines; CT26 syngeneic CRC model in Bagg Albino (BALB/c) mice | ✓ | ✓ (GM-CSF → ↑ Dendritic cells, ↓ Tregs/Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSC), ↑ CD4+/CD8+ T cells) | ✖ | Necrosis (inflammatory cell death), cell cycle–independent killing | [28] | |||

| oHSV2 (Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2) | Preclinical (in vivo) | CT26 syngeneic CRC model in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (T cells, B cells, Natural Killer cells, and neutrophils) | ✖ | N/A | [29] | |||

| G207 & NV1020 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 5 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in male athymic mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | [30] | |||

| Herpes simplex virus type-1 (G207) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 5 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in athymic rats; liver metastasis model in Buffalo rats | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis via γ34.5 deletion | [31] | |||

| Paramyxoviridae (and Matonaviridae) | rMV-SLAMblind | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | DLD1 and HumanTumor29 CRC xenograft models in SCID mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | [32] | ||

| PPRV M protein (matrix) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 human CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | BH3-like motif → Bax activation; intrinsic apoptosis | [33] | |||

| Live-attenuated measles virus (Schwarz MV-eGFP) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human CRC cell lines; Caco-2 xenograft model in nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | CD46-mediated tumor selectivity; caspase-3-dependent apoptosis | [34] | |||

| Newcastle disease virus AF2240 (velogenic) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 7 human CRC cell lines (including p53 variant lines) | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | [35] | |||

| Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) | Preclinical (in vivo) | Murine CRC | ✓ | ✓ TME remodeling, innate + adaptive activation | ✖ | N/A | [36] | |||

| Picornaviridae | Human enterovirus B species echovirus 12, 15, 17, 26 and 29 | Preclinical (in vitro) | 6 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis triggered by receptor binding (E12/E15, replication-independent) | [37] | ||

| Poxviridae | Orf Virus (ORFV) strain NA1/11 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 7 CRC cell lines (human + murine); CT26 syngeneic model in Balb/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ Interleukin-7, IL-13, IL-15, IL-21, CD27, CD30, CXCL13 → activation of T cells, NK cells, B cells) | ↓ VEGF-B, ↓ Delta-like Ligand 4 | Apoptosis (15 cytokines upregulated, CD27–SIVA pathway). | [38] | ||

| oncolytic vaccinia virus GLV-1h68 | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 5 Human CRC cell lines; Xenograft in athymic rats | ✓ | ✓ (↑ IFN-γ, IP-10, MCP-1/3/5, RANTES, TNF-γ; ↑ macrophage and NK infiltration) | ✖ | IFN suppression; necrosis-driven immune influx | [39] | |||

| CF33-Fluc | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in athymic nude mice | ✓ | ✓ (Necroptotic death; ↑ calreticulin, High Mobility Group Box 1 protein (HMGB1)) | ✖ | Necroptosis | [40] | |||

| Reoviridae | Reovirus T3D | Preclinical (in vitro and ex vivo) | 4 human CRC cell lines; human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) and Liver Mononuclear Cells (LMC); 1 murine fibroblast line (L929) | ✓ | ✓ (NK activation via Type I IFN; PBMC and LMC degranulation and cytotoxicity) | ✖ | Innate immune effector activation in the liver | [41] | ||

| Pelareorep | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo, ex vivo PBMCs) | 2 human CRC cell lines (KRAS mutant and WT isogenic pair); BALB/c and C57BL/6 mouse models | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Autophagy induction precedes apoptosis | [42] | |||

| Rhabdoviridae | Vesicular stomatitis virus M51R/ΔM51 | Preclinical (In vitro) | 1 human CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Apoptosis; M-protein mutation disables interferon suppression | [43] | ||

| Vesicular stomatitis virus (rwt and M51R mutant) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 human CRC cell lines; RKO and LoVo xenograft models in athymic nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis induction | [44] | |||

| Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC cell line; 2 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Syncytia formation and suicide gene strategies to enhance killing | [45] | |||

| (b) | ||||||||||

| Virus Family | Virus | Trial Phase | Trial Status | Patient Population | Delivery Route | Adverse Events | Outcomes/Endpoints | Quantitative Information | Citation | |

| Poxviridae | Pexastimogene devacirepvec JX-594 | Phase Ib | Completed | N = 15 CRC-only (metastatic, refractory) | Intravenous infusion, biweekly | Mostly fever, chills, mild constitutional symptoms | Endpoint: safety + tumor response. Outcome: 10/15 had stable disease (SD); 5/15 had progression; no objective regressions | 67 percent SD (10/15); 33 percent PD (5/15); no measurable shrinkage | [46] | |

| Pexa-Vec (oncolytic vaccinia virus) | Phase Ib | Completed | N = 6 Colorectal cancer liver metastases, neoadjuvant setting | Single 1 h intravenous infusion of 1 × 109 pfu Pexa-Vec | Grade 3–4 lymphopenia/neutropenia | Endpoint: detect virus in tumor. Outcome: Virus found in 3/4 tumors; 2/6 showed major necrosis; 3/6 long-term cancer-free | Virus detected 3/4; major necrosis 2/6; long-term survivors 3/6 | [47] | ||

| Reoviridae | Reovirus | Phase I | Completed | N = 5 KRAS-mutant metastatic CRC | IV infusion, 60 min/day × 5 days | No major safety findings reported | Endpoint: immune activation. Outcome: All showed APC and CD8 activation; miR-29a ↓; granzyme B ↑ | Anti-tumor cytokines ↑; IL-8/RANTES ↓; granzyme B ~4× increase | [48] | |

| Reovirus | Clinical End-Point Trial | Completed | N = 10 metastatic CRC with liver metastases | Intravenous infusion of 1010 units reovirus | Fever/flu-like symptoms (6/10) | NK activation and IFN-I peak at 24–48 h, lost by 96 h; no re-activation with more doses | NK markers and ISGs peak 24–48 h; NK count ↑ up to 6–13×; no tumor response data | [49] | ||

| (a) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Family | Virus | Study Type | Model/Cell Type | Direct Oncolysis | Immune Activation | Angio Targeting | Other Mechanism | Combination Therapy | Synergistic Effect | Citation |

| Adenoviridae | CD55-TRAIL oncolytic adenovirus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 human CRC cell lines; mouse xenograft model | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Apoptosis | Luteolin | ✓ | [50] |

| Type 5 Oncolytic Adenovirus (Ad5-hTERT-E1A) | Preclinical (in vivo) | 2 murine CRC models (CT26, MC38) in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+ T cells, ↑ IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells, ↑ ICOS) | ✓ (disrupted tumor neo-vasculature) | N/A | PLX3397 (CSF-1R inhibitor) + anti-PD-1 | ✓ (↑ tumor control, ↑ survival; CT26: 43%, MC38: 82%) | [51] | |

| Telomelysin (OBP-301) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 human CRC cell line with PBMC and splenocyte coculture; HT29 rectal xenograft and lymph node metastasis mouse model | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Viral replication and trafficking suppressed lymph node metastasis | Ionizing radiation | ✓ | [52] | |

| H101 (Oncolytic Adenovirus) | Case Report | Patient with recurrent abdominal LN metastasis | ✓ | ✓ (↑ NK activation, ↑ CD8+ T cells, M1 polarization, ↓ MDSCs) | ✖ | N/A | Capecitabine (low-dose oral chemotherapy) | Complete response in 12 cm LN metastasis; Progression-Free Survival = 19 months; immune modulation | [53] | |

| Adv-CXCL10 | Preclinical (In vitro and in vivo) | 2 murine CRC cell lines; MC38 syngeneic mouse model | ✓ (only in vitro) | ✓ (T cell recruitment; ↑ IFN-γ and granzyme B in TME) | ✖ | Bystander effect, hypoxia induction | Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy | ✓ (by remodeling an antitumour immune microenvironment) | [54] | |

| ZD55-Dm-dNK | Preclinical (In vitro) | 2 human CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Suicide gene (Dm-dNK) activation of NA triggers selective apoptosis | Nucleoside analogs (BVDU, dFdC, ara-T) | ✓ | [55] | |

| Ad5/3-pCDX2 (CDX2-promoter oncolytic adenovirus) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC cell lines; subcutaneous xenografts and liver metastasis model in nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) | ✓ | [56] | |

| Wnt-targeted NTR-armed adenovirus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 4 human CRC cell lines; SW620 xenograft model in NMRI nu/nu mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ | Bystander killing effect | CB1954 prodrug + RAD001 (everolimus) | ✓ | [57] | |

| rAd.DCN | Preclinical (In vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in female NPG mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ NK proliferation, infiltration, degranulation; ↑ perforin, IFN-γ) | ✓ (VEGF inhibition) | Decorin gene (delivered via rAd.DCN) targets TGF-β, Met and Wnt/β-catenin pathways | adoptive NK cell therapy | ✓ | [58] | |

| CRAdNTR | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 p53-mutant human CRC cell lines; HT29 xenograft model in Balb/c mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Gene-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy (GDEPT) | prodrug CB1954 | ✓ | [59] | |

| Herpesviridae | Oncolytic herpes virus C-REV | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 human CRC cell lines; xenograft model in mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✓ (↓ VEGF, Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF), and TGF-α) | N/A | Cetuximab | ✓ in vivo only | [60] |

| oHSV (HSV-1 ∆810) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC cell line; MC38 syngeneic CRC model in C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+/CD4+ infiltration; ↑ DC recruitment and activation) | ✖ | Immunogenic cell death and necroptosis | Low-dose mitomycin C + anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4 | ✓ | [61] | |

| oHSV2 (type II HSV-2 ICP47/ICP34.5-deleted) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human DLBCL cell lines; 4 xenograft model in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD4+/CD8+ infiltration; ↑ granzyme B and perforin) | ✖ | PD-L1 down-regulation; CTL activation | Anti-PD-L1 antibody | ✓ (strongest tumor inhibition; complete regression in 1/8 mice) | [62] | |

| T1012G | Preclinical (in vivo and in vitro) | 3 human CRC cell lines; 2 murine CRC lines; xenograft models in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ↓ VEGF secretion; ↓ Tumor angiogenesis | N/A | propranolol | ✓ | [63] | |

| Paramyxoviridae | Newcastle disease virus (LaSota) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 human CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Intrinsic apoptosis (↑ caspase-9) | Bacillus coagulans ± 5-FU | ✓ | [64] |

| Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) | Preclinical (In vitro) | 1 murine CRC cell line; MSCs from BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (caspase-8/9 activation; LDH release; Th1, CTL, NK responses) | ✖ | ↑ apoptosis via intrinsic and extrinsic pathways; ROS-mediated stress | Lactobacillus casei extract | ✓ (Enhanced apoptosis, ROS, and LDH levels vs. monotherapy) | [65] | |

| Picornaviridae | Coxsackievirus A11 (CVA11) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC cell lines (oxaliplatin-sensitive and resistant); WiDr xenograft model in BALB/c nude mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | Oxaliplatin | ✓ (↓ tumor volume & ↑ survival vs. monotherapy) | [66] |

| Coxsackievirus B3 (PD-H) | Preclinical (in vitro) | 1 refractory human CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | FOLFOXIRI (oxaliplatin + SN-38 + 5-FU/folinic acid) | ✓ (synergistic cytotoxicity across all tested doses) | [67] | |

| V937 (Coxsackievirus A21) | Preclinical (in vitro) | CRC cell lines ± PBMCs; CRC organoids ± PBMCs | ✓ (ICAM-1+) | ✓ (with PBMC: ↑ cytokines; innate + adaptive responses) | ✖ | N/A | Pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) | ✓ | [68] | |

| Poxviridae | Vaccinia virus (vvDD- Somatostatin Receptor) | Preclinical (in vivo) | CT26 murine CRC peritoneal carcinomatosis model in mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Bystander effects (radiation + OV danger signals) | 177Lu-DOTATOC (peptide-receptor radiotherapy) | ✓ | [69] |

| vvDD-mIL2 (oncolytic vaccinia virus) | Preclinical (in vivo) | MC38-luc syngeneic CRC model in C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+ T cells, ↑ TNF-α+ CD8+, ↑ IFN-γ+ CD4+, ↑ CD8+/Treg ratio) | ✖ | Membrane-tethered IL-2 delivers localized IL-2 | CpG ODN (TLR9 agonist) | ✓ (slowed growth of contralateral tumors; ↑ median survival 27–33%) | [70] | |

| vvTRAIL (TRAIL-armed vaccinia) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines and 1 murine CRC line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | TRAIL-triggered apoptosis | Oxaliplatin | ✓ | [71] | |

| oncolytic poxvirus (vvDD-CXCL11) | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 1 murine CRC line; MC38 peritoneal carcinomatosis model in C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ | ✖ | N/A | CKM (IFN-α, poly I:C, COX-2 inhibitor) | ✓ | [72] | |

| Oncolytic Vaccinia virus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 2 human CRC lines; 1 murine CRC line (MC38); xenografts in BALB/c nu/nu mice | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | irinotecan (SN-38 in vitro; CPT-11 in vivo) | ✓ (Strong synergy in vitro; only DLD1 model translated to in vivo model synergy) | [73] | |

| Oncolytic Vaccinia virus | Preclinical (in vivo) | MC38 subcutaneous tumors in C57BL/6 mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ NK cells, ↑ CD8+ T cells, ↓ MDSCs, ↑ antitumor responses, ↑ immune memory) | ✖ | N/A | anti-CTLA4 antibody, anti-CD25 antibody, | ✓ | [74] | |

| Reoviridae | ReoT3D | Preclinical (In vitro) | 1 murine CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑ Apoptosis via caspase + STAT3 and KRAS downregulation | CPT-11 (irinotecan), BBI608 (napabucasin) | ✓ (↑ apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, gene regulation) | [75] |

| Reovirus | Preclinical (In vitro) | KRAS mutant CRC cell lines | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | ↑Autophagy, ↑ Apoptosis | Carbamazepine | ✓ (combo > mono) | [76] | |

| Reovirus | Preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) | 3 murine CRC cell lines; CT26 subcutaneous tumor model in BALB/c mice | ✓ | ✓ (↑ CD8+ T cell trafficking; ↑ IFN-β expression) | ✖ | N/A | STING agonist (ADU-S100) | ✓ | [77] | |

| Reovirus (ReoT3D) | Preclinical (In vitro) | 1 murine CRC cell line | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | Induction of apoptosis | Irinotecan + Metformin + MSC-derived ReoT3D secretome | ✓ (increased apoptosis and reduced cell viability) | [78] | |

| Reovirus T3D | Preclinical (in vivo) | C26-luc murine CRC liver metastases; BALB/c mice ± CyA | ✓ | ✖ | ✖ | N/A | Cyclosporin A (immunosuppressant) | ✓ | [79] | |

| Rhabdoviridae | VSVΔ51 | Preclinical (in vitro, in vivo, organoid) | Drug-resistant CRC lines (5 human, 1 murine); CRC organoids; HCT116/OXA (nude) and MC38/OXA (C57BL/6) | ✓ | ✓ (↑ NK infiltration, Granzyme B, IFN-γ, CD107a) | ✖ | Necroptosis | TBK1 inhibitor (GSK8612 or MRT67307) | ✓ (↑ viral replication and oncolysis; complete tumor regression in 1/5 mice) | [80] |

| (b) | ||||||||||

| Virus Family | Virus | Combination | Trial Phase | Trial Status | Patient Population | Delivery Route | Adverse Events | Outcomes/Endpoints | Quantitative Information | Citation |

| Adenoviridae | Enadenotucirev | nivolumab | Phase I | Terminated Early | N = 51 45 CRC (mostly MSS/MSI-L), 6 SCCHN | IV enadenotucirev + IV nivolumab | 61% grade 3–4; anemia, infusion reactions, hyponatremia, bowel obstruction; AKI/proteinuria signal | MTD not reached; minimal activity (ORR 2%, SD 45%); strong CD8+ immune activation | PFS 1.6 mo; OS 16 mo; 12-mo OS 69%; CD8 ↑ in 12/14 | [81] |

| Onyx-015 | 5-FU and leucovorin | Phase I/II | Completed | N = 24 Metastatic CRC | Hepatic artery infusion Onyx-015; later combined with IV 5-FU/LV | No DLTs; treatment well tolerated across ~200 infusions | PR 2/24; SD 11/24; transient tumor swelling before necrosis | Median OS 10.7 months; 1-year OS 46 percent; SD subgroup OS 19 months | [82] | |

| Herpesviridae | NV1020 (Herpes Simplex Virus) | Intra-arterial chemotherapy (floxuridine ± irinotecan/oxaliplatin) | Phase I | Completed | N = 12 Metastatic CRC with liver-only disease | Hepatic arterial infusion (single dose) | No HSV-related toxicity; no viral reactivation | Early biologic effect before chemo; CEA decline; some tumor shrinkage; all patients had partial response once chemo began | CEA drop 13–74%; tumor shrinkage in 2/12 (up to 39%); median survival 25 months | [83] |

| T-VEC | Atezolizumab | Phase Ib | Completed | N = 34 TNBC (N = 10); CRC (N = 24) | Intratumoral hepatic injection + IV atezolizumab | Grade ≥3 AEs: TNBC 70%, CRC 54%; DLTs: 0 in TNBC, 3 in CRC; 1 fatal AE (CRC) | Very limited activity; TNBC ORR 10%; CRC ORR 0% | TNBC: 1 PR (10%), PFS 5.4 months, OS 19.2 months; CRC: ORR* 0%, PFS 3 months, OS 3.8 months | [84] | |

| Poxviridae | Oncolytic vaccinia virus (TG6002) | TG6002 (HSV-1 + FCU1) + oral 5-FC | Phase I | Completed | N = 15 Liver-dominant mCRC | Intrahepatic artery infusion of TG6002 + oral 5-FC | 14/15 AEs; 5/15 grade 3; 1 DLT (grade 3 MI) | Safety achieved; no RECIST responses | Virus/FCU1 detected in 10/13 tumors; PFS 1.05 mo; OS 5.4 mo | [85] |

| Pexastimogene devacirepvec (oncolytic vaccina virus) | Tremelimumab (anti–CTLA-4) + Durvalumab (anti–PD-L1) | Phase I/II | Completed | N = 34 pMMR metastatic CRC, chemo-refractory | IV PexaVec + IV ICIs | Fever/chills common; 3 immune-related toxicities (colitis, myositis); 1 hypotension → discontinuation | Safety/feasibility met; minimal antitumor activity | 1 PR (51% shrinkage); SD in 4 pts; PFS 2.1–2.3 mo; OS 5.2–7.5 mo | [23] | |

| Reoviridae | Pelareorep | FOLFOX6 + bevacizumab | Phase II | Completed | N = 103 Metastatic CRC | IV | More neutropenia, hypertension, proteinuria; more bevacizumab discontinuation | Pelareorep increased ORR but worsened PFS; OS unchanged | PFS 7 vs. 9 mo; ORR 53% vs. 35%; response duration 5 vs. 9 mo; OS 19.2 vs. 20.1 mo | [86] |

| Pelareorep | FOLFIRI/Bevacizumab | Phase I | Completed | N = 36 KRAS-mutant mCRC | IV pelareorep + FOLFIRI ± bevacizumab | Neutropenia, anemia, diarrhea, fatigue; fever; bevacizumab-related proteinuria | High disease control; partial responses at highest dose | PR 3/6 at RPTD; overall PR 6/30; SD 22/30; PFS 65.6 wks (RPTD); OS 25.1 mo (RPTD) | [87] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salameh, H.; Naseem, N.; Chattha, M.A.; Ramesh, J.; Ramy, H.; Cizkova, D.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Oncolytic Virotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanistic Insights, Enhancer Strategies, and Translational Combinations. Cells 2025, 14, 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242006

Salameh H, Naseem N, Chattha MA, Ramesh J, Ramy H, Cizkova D, Kubatka P, Büsselberg D. Oncolytic Virotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanistic Insights, Enhancer Strategies, and Translational Combinations. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalameh, Huda, Nesha Naseem, Muhammad A. Chattha, Joytish Ramesh, Haneen Ramy, Dasa Cizkova, Peter Kubatka, and Dietrich Büsselberg. 2025. "Oncolytic Virotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanistic Insights, Enhancer Strategies, and Translational Combinations" Cells 14, no. 24: 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242006

APA StyleSalameh, H., Naseem, N., Chattha, M. A., Ramesh, J., Ramy, H., Cizkova, D., Kubatka, P., & Büsselberg, D. (2025). Oncolytic Virotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanistic Insights, Enhancer Strategies, and Translational Combinations. Cells, 14(24), 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242006